Using Music as a Therapy Tool to Motivate Troubled Adolescents

SUMMARY. Children and adolescents with emotional disorders may often be characterized by having problems in peer and adult relations and in display of inappropriate behaviours. These include suicide attempts, anger, withdrawal from family, social isolation from peers, aggression, school failure, running away, and alcohol and/or drug abuse. A lack of self-concept and self-esteem is often central to these difficulties.

Traditional treatment methods with young people usually includes cognitive-behavioural approaches with psychotherapy. Unfortunately these children often lack a solid communication base, creating a block to successful treatment. In my private clinical practice, I have endeavoured to break through these communication barriers by using music as a therapy tool.

This paper describes and discusses my use of music as a therapy tool with troubled adolescents. Pre- and post-testing of the effectiveness of this intervention technique by using the Psychosocial Functioning Inventory for Primary School Children (PFI-PSC) has yielded positive initial results, lending support to its continued use.

Music has often been successful in helping these adolescents engage in the therapeutic process with minimised resistance as they relate to the music and the therapist becomes a safe and trusted adult. Various techniques such as song discussion, listening, writing lyrics, composing music, and performing music have proven to be useful in reaching the child, facilitating self-expression, projecting personal thoughts and feelings into a discussion, enhancing self-awareness, stimulating verbalization, providing a pleasurable, non-threatening environment, facilitating relaxation, and reducing tension and anxiety. I have found that by using music in this way, the distrustful adolescent has come to regard me as a positive adult. Music has thus provided a safe, non-confrontative means of expression. This has helped in creating more socially acceptable ways of venting anger and fears, increasing self-awareness, self-confidence, and self-esteem. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Music, adolescents, post trauma stress, therapy

THE DIFFICULTIES OF INTERACTING WITH ADOLESCENTS IN THE THERAPY SITUATION

In South Africa today most if not all children are at risk. They are regularly confronted by news of tragedies–the TV and media are packed with images of murder, hijacking, hold-ups, assaults, break-ins, senseless shootings, school violence, tragic taxi, bus and other motor accidents, as well as other community disasters–flooding, fires, and so on. Many children are more directly impacted by crime and violence as they become the targeted victims or are the innocent bystanders (Lewis, 1999).

Children are unprepared for and have a limited capacity to understand and deal with these traumatic situations. They are forever changed. Often the only way that they can express the effects of such intense stress and anxiety in their lives is in their outward behaviour. It is therefore not uncommon to see adolescents presenting with deterioration in academic performance, aggressiveness or withdrawal from peers, a decreased enjoyment in and motivation towards activities and hobbies, tobacco, alcohol and drug abuse, promiscuous sexual and risk taking behaviour, irritability and excessive rebelliousness at home, insomnia and other somatic symptoms such as weight loss, headaches, and general aches and pains. Although emotional turbulence with negative behaviour often accompanies the emerging adolescent as he or she grapples with the difficulties of assuming adulthood, the behaviours I have described are often so uncharacteristically intense and forceful in nature that further exploration is necessary. It is at this point that the emotional scarring as a result of being the victim or witness to a traumatic event surfaces (Alexander, 1999).

Adolescents often find it difficult to communicate their feelings to an adult, and by the very nature of their “anti-social” behaviours are then confronted with a battlefield of demanding and critical parents, teachers, and other significant adult figures. It is therefore not unusual to find the teenager sitting beside you in therapy, having been forced there by his or her parents, suspicious and antagonistic towards yet another “authority” figure. They are as yet unskilled in expressing their real feelings, they do not trust the counsellor, and they perceive themselves to be in another situation where demands for which they are unprepared, are going to made on them. It is no wonder that this teenager may remain unresponsive and cannot wait to be “released” from the therapy session!

Being exposed to trauma has emotionally wounded these adolescents. Their lives will never be the same. Untreated, the effects may last a lifetime and leave them hopeless and vulnerable to chronic depression and even suicide.

USING MUSIC AS A THERAPY TOOL WITH ADOLESCENTS

In my practice situation, music has shown itself to be useful as one journeys through the heart, mind, body, and soul of teenagers suffering from the trauma of having been raped, having been involved in horrific accidents, and having to come to terms with losing a loved one, losing a limb, or receiving a spinal cord injury resulting in permanent paralysis, having been violently hijacked, experiencing the trauma of confronting a burglar in their homes, or being physically assaulted (Keen, 1989; Gaston, 1968). This paper presents the use of music as a means to interact with adolescents in order to gain their trust and confidence, so that the healing process may be facilitated to regain their appreciation for life and themselves. To illustrate more effectively, one case example is presented.

Assessment

The Problems Presented

Tracey, aged 13 years, was brought to me by her mother who indicated that she was at her wits’ end with her daughter. Tracey is the youngest of four siblings. She attends an exclusive private girls’ school. Her father is a prominent medical doctor, and her mother has raised all four children at home. What follows is part of what Tracey’s mother told me in my initial consultation with her alone:

Last weekend, Tracey had two of her close friends visiting her … They went to play badminton on the lawn … things went wrong … Tracey stormed upstairs … when I went to talk with her, she burst into tears and a tirade followed: “You don’t love me … You don’t want me for a daughter … You should have dumped me when I was born… I’m going to live in Brazil, far away from you and leave you in an old age home…” She wouldn’t let me hug or touch her. The next afternoon (after another seemingly small situation going wrong), Tracey snapped at me again: “Why don’t you put me in a black refuse bag and dump me on the street? You can all have a big grin then.” Tracey went and hid in the garden. She later grazed her knee from a fall. That night, she wouldn’t let me kiss her goodnight. She turned and faced the wall and started to shout at me again: “You don’t know how sore this knee is … You don’t care at all about it …” She performed about how she would have to keep her leg out of the blankets, how cold it would be, but it was too sore, and nobody cared how cold she would be. I’ve noticed that this year Tracey is not so responsible with her schoolwork. She loses work that she has completed, then there is a panic, and abuse hurled at me because she can’t find it and I’m not helping. She forgets to take the necessary work to school, forgets to bring home the right books for homework, and is generally not coping as well with school as she has in the past. She doubts herself, lacks self-confidence and won’t try anything. She is causing immense tension in the home. She is sulky, rude, slams doors, complains about pains and when I ask her what is wrong she retorts: “You don’t care … You don’t help…You don’t listen to me, one day I won’t speak anymore …” She is jealous if our dogs lie by me or sit on my lap. She says the dogs are doing it to show her they prefer me. She recently pulled out a chair making a big noise. I rushed in because I thought she had fallen. Tracey: “ Well, would it have mattered if I’d fallen?” She has stopped playing tennis or swimming at school, saying that people laugh at her… that they don’t want her in the team. She says: “Funny I was a good swimmer. Now I’m not. I can’t do anything right.” When she is sick she complains that nobody is interested in her: “I wish there was someone who cared about me. I’ve got diarrhoea. I never told you this morning because I know you wouldn’t care or do anything about it.” When her granny has phoned and asked to speak to her, she has refused to pick up the telephone. “Gran is so mean. She always says how gorgeous Sarah (Tracey’s older sister) was as a baby. She’s not really interested in me.” After a small altercation with her father, Tracey stormed off with: “All I want is to be a wanted child. You never know one day I may end up in the streets begging. Everything’s wrong with me.” Other statements have included: “Why didn’t you just kill me when I was born?” “Why don’t you kill me and take me to an orphanage?” She is scared of sleeping alone. If she is playing games with her friends and starts to lose, she stops trying. She won’t go on school excursions, complains of having a sore tummy. At home it’s like living on an active volcano. We are never sure when and how she is going to erupt. As a result there is enormous tension at home. Her teachers like her but say she lacks confidence; she won’t answer questions or talk in a group. I am so hurt by what Tracey says and how she treats me. I try to be very tolerant, supportive, understanding, and not to correct her too often–but I’m not winning. It’s difficult to know how to correct or discipline her–whichever way I try it ends up with her saying she is “unloved.” I am now finding it very difficult to enjoy being at home with her, and am finding it very hard to enjoy her company. Please help me–I’m at my wits’ end!

Music in the Initial Consultations

In my first session with Tracey, as she was not forthcoming about herself, I chatted to her about myself in an attempt to help her feel more comfortable with me. As I knew that she would be attending a concert of a visiting Irish pop group, Westlife, we listened to some of their music that I had brought to the session. Adolescents generally relate to the music of their peer culture, and find it easier to express themselves and their feelings when familiar music is playing. In this instance the music provided a safe, non-threatening environment where the therapist-client relationship was significantly enhanced. She visibly relaxed, smiled and at the end of our time together, agreed to complete an open-ended questionnaire entitled “Discovering Myself !” at home and to see me again. At the subsequent session, Tracey returned the homework, which had been neatly completed and then, whilst appropriate pop music was played in the background, she willingly answered the Child Functioning Inventory for Senior Primary School Children (CFI-Snr Prim). When one knows that this session will be used to complete any assessments, it is often useful to ask the adolescent to bring one or two CDs of her favourite music with her. This is the music that is then played, allowing the teenager to feel “at home” and empowered and provides a further opportunity for relationship and trust building. Music is a familiar and therefore a “safe” medium to most adolescents. Using a technique such as song discussion and listening is a non-confrontative tool, which often facilitates the projection of personal thoughts and feelings into the therapy session.

Results of Assessment

The social work profession over the last two decades has made great strides in its development of high-quality measurement tools to improve its effectiveness and accountability in service delivery. Since children are less verbal and less powerful than adults in the traditional family hierarchy, the therapist working with a child has to move quickly to empower the child and to incorporate his/her perceptions of the world. The Child Functioning Inventories (CFI) have been developed and validated by the Perspective Training College (South Africa).

The CFI-Snr Prim is a paper and pencil self-report measure designed to evaluate the social functioning of children between the ages of 13 and 18 years by obtaining an assessment of child problems in 24-28 different areas of functioning. The results of the CFI are graphically presented. This visual profile facilitates clinical discussions with clients.

The results of the CFI-Snr Prim completed by Tracey indicated the following:

Section A: Positive Functioning Areas

Perseverance (72), Satisfaction (81), and Future Perspective (75): These results were all in the recommended range with an overall score of 76%.

Section B: Self-Perception

Anxiety (62 *), Guilt feelings (44 *), Lack of self-worth (31), Isolation (18), Responsible for consequences against others (75 *), Lack of assertiveness (56 *). (see Graph 1)

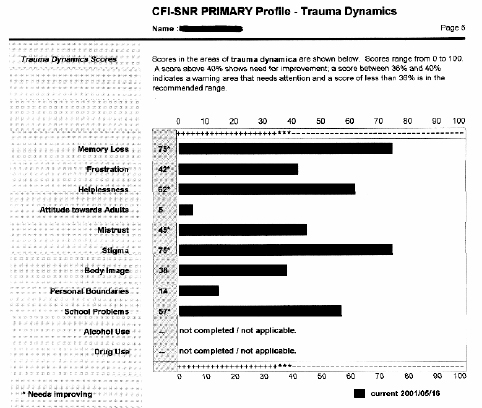

Memory loss (75 *), Frustration (42 *), Helplessness (62 *), Attitude towards adults (5), Mistrust (45 *), Stigma (75 *), Body Image (38), Personal Boundaries (14), School problems (57 *), Alcohol/Drug use (Not completed/not applicable).

The overall score was 45%. Scores above 40% (*) indicated problem areas. Graphic results of these scores may be seen at the end of the paper (see Graph 2).

Section D: Relationship Scores

Relationship with friends (93), Relationship with mother (100), Relationship with father (68), Relationship with family (81): Overall score was 85%. Scores of less than 60% indicate a need for improvement, and thus Tracey’s scores were all within the recommended range.

The Overview Profile of all these results indicated that Tracey’s self perception and trauma dynamics sometimes impair her positive functioning areas and relationships to the extent that she cannot always deal with them in an effective way. Her overall functioning was therefore described as being fluctuating pointing to an adolescent who was troubled and possibly the victim of some kind of trauma.

Using Music To Facilitate Emotional Discussion

When showing her the graphs and discussing these results with her, Tracey broke down crying. The use of background music during this discussion (e.g., an acoustic guitar playing Cavatina by Myers) will often facilitate and ease the way for an adolescent to share emotional issues. The therapeutic process is enhanced as well as resistance being lowered because the adolescent client is “tuned-in” to the music and not the therapist whose role as a safe and trusted adult is accepted. In this consultation with Tracey, with limited verbal encouragement from the therapist, just soft, soothing background music playing, the following story emerged:

When coming home in the car with my Mom from Church on a Sunday night in 1998 (NB: 2 years, 8 months prior to my seeing Tracey) I was talking to her about how everyone should wear seatbelts, when suddenly we saw headlights coming straight for us. My Mom didn’t have time to swerve away but she slammed on brakes. I managed to put my hand on the dashboard but before we knew it, we had been hit and glass was shattering all around me. When I realised what had happened, I looked across to my Mom to see if everything was OK. Her head was on the steering wheel with her eyes closed and blood was streaming down her face. I shouted to her: “I love you Mom!” and just kept on calling “Mom! Mom! Mom!” but there was no reply. Someone opened my door, asked if I was OK and helped me out of the car. After I had given this person my home telephone number, she phoned my Dad and brother to come. She then went to my Mom. Another person came to me and asked me if anything hurt. I told her that my thumb and hand did. This person fetched a blanket and umbrella for me because it was raining. Two ambulances arrived. One took me to hospital accompanied by my brother’s girlfriend who had arrived with him and my Dad. When I arrived at the hospital I had x-rays, and a doctor put a plaster of paris cast on my left arm and a neck brace. I felt really uncomfortable and actually thought I was going to die! After that, I was put in a wheelchair, and my brother’s girlfriend took me to where the trauma unit staff was by now working on my Mom. I only saw her for a split second. She was lying on a stretcher, with a bandage wrapped the whole way around her head, and her eyes were closed. She was then wheeled away and I heard a nurse say: “This is a bad one!” I was then taken home. I wasn’t hungry, as I knew my Mom could be dead. I went to bed very uncomfortable. I couldn’t sleep. I was worrying so much.

Final Assessment

Tracey’s responses, results of the CFI-Snr Prim, her behaviours as described by her Mom, Dad, family and teachers, all pointed to an assessment of a chronic Post Traumatic Stress Disorder with delayed onset (309.81) as described by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition) (1994)–DSM-IV.

GRAPH 1. Self-Perception Scores CFI-Snr Prim (Tracey)

GRAPH 2. CFI-Snr Prim Trauma Dynamics Scores (Tracey)

Upon further investigation, it was found that Tracey’s mother had been unconscious for two days, and had remained in hospital for over a month, most of the time being cared for in the Intensive Care Unit. She subsequently had to return to hospital on two further occasions for orthopaedic treatment. During this period, the family’s focus was on Tracey’s mother–more so with her father being a doctor. Tracey was sometimes left alone with strangers or her granny. When with groups of people or in the family, all they spoke about was her Mom. She just had to “get on with things” such as returning to school and particularly being available to help around the home because her mother was not there, or her mother was unable to move or walk when she did return home. In addition, the family had to support her Mom through a criminal court hearing whilst she gave evidence in the trial of the driver of the other vehicle who had been charged with reckless and drunk driving after the accident. Tracey has been attempting to cope with the emotional trauma of being injured in a serious motor accident, very nearly losing her mother in the accident, and overwhelming family and friend support for her mother over an extended period. It is understandable that this girl who was 10 years at the time is now reacting to her perceived reality of not being important to the family and is expressing these toxic emotions in negative attitude and behaviour towards her mother who she perceived as having received all the care and attention.

When all this emerged, it made sense to Tracey’s mother, father, and family. The restoration and healing process was initiated. The initial focus has been on Tracey, with active affirmation and positive reinforcement for all achievements, however small. The expectations of her day-to-day performance and activities at school and at home have been lowered. She has been regularly reassured about her seemingly confused, and frightening fears and thoughts. Her parents and family have been encouraged to indulge Tracey’s special needs for a time so that a sense of personal and family security may be reconstructed.

Intervention

Using Music To Enhance the Healing Process

During the individual sessions with Tracey, she has been encouraged to re-tell and to re-experience the “accident.” Music has played a constructive part in this. Tracey has first been taught progressive relaxation techniques accompanied by soothing relaxation type music. Music has helped to prevent her mind from wandering and has reinforced her ability to focus on relaxation. Harp music and sounds of the ocean and nature have been particularly useful in this process. She has then been taught to focus her thoughts on the present moment, again accompanied by familiar music. At this point, in a state of deep muscle relaxation, a “special personal place” where she can express her thoughts and feelings in safety has been created through a visualization process. Together we have created a seaside scene, where her senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch have been acutely sensitised by vivid descriptive imagery (Bourne, 1995). For example:

Imagine yourself walking along a very beautiful, expansive beach… the sand is very fine and white in appearance … feel it between your toes … hear the roaring sound of the surf … watch the waves … the colour of the ocean is a relaxing shade of blue … notice a tiny sailboat skimming easily across the surface of the sea … take a deep breath and take in the fresh, salty smell of the sea air … notice a seagull flying gracefully across the waves … imagine yourself having the freedom to fly … feel the sea breeze blowing against your face … the warmth of the sun on your shoulders …

Using the same piece of music on each occasion has assisted Tracey to “enter” this special place by herself. She is then able to use this music at home, when travelling in the car or elsewhere to enhance a sense of wholeness and well-being. Once she has visualised herself in this place, and feels emotionally safe, therapy has consisted of using slow, emotive classical music, e.g., the Violin Concerto No 1 in G Minor, Opus 26–Adagio by Bruch, to guide the imagery process back to the accident, encouraging desensitisation to physical reaction whilst allowing emotional expression to personal feelings. The music has facilitated a cognitive engagement whilst reinforcing relaxation during the “re-living” of the stressful event. Upon conclusion of the music, Tracey has been emotionally drained but has expressed feelings of warmth, safeness, closeness to family members, especially her mother, of being at peace within herself and a general sense of contentment.

The playing of a theme song jointly chosen has at this point concluded therapy. Generally such theme songs should be positive, engender a sense of courageousness and hope for the future. For Tracey this has been the song by Mariah Carey entitled The Hero.

Evaluation of the Therapy Process

Therapy has still to include other family members although Tracey’s mother has been included as an important part of this initial process. Post therapy results using the CFI-Snr Prim as the test instrument has shown positive changes. Tracey has been encouraged to write letters to her mother and father.

Significant parts of these letters include:

Dear Mom,

… You are the greatest mom ever. You always care for me in such a unique way. You will always stay in my heart as the sweet, kind person who always makes me happy! Thank you for always understanding and loving me and for being there when I need you …

Dear Dad,

… Thank you for asking how my day was. Thank you for being willing to listen to me when I don’t make sense. Please could you help me with practising tennis? …

Although there are still essential changes to take place, it is important to note that Tracey has made crucial strides in a short space of time. Initial assessment using the CFI-Snr Prim assisted positively in identifying areas of concern and opening up the possibility of a previous traumatic incident. The non-verbal aspect of the music used made it an excellent resource for reaching this adolescent and facilitating self-expression. The music used provided a relaxing, non-threatening environment where Tracey was able to safely risk trying new experiences that could then be transferred to other areas of her life. Within two sessions, Tracey was able to regard the adult therapist as a friend and important role model. Music afforded Tracey the opportunity to express her fears, anger, and hurts in a non-confrontative environment where levels of tension and anxiety were reduced. Her defences were lowered and she found herself more motivated to attempt life tasks again. More appropriate co-operative behaviours were noticed within the home environment.

In this paper, the deliberate but careful use of music to reach a traumatised adolescent has been described. Because of its non-verbal, creative and emotional qualities it proved to be a useful technique in the therapy process. In the case example given, music provided a constructive tool for the therapist to establish a therapeutic relationship, to facilitate interaction, self-awareness, and personal change within a relatively short period of time. The motor accident that Tracey survived did not make headlines. It was an explosion of glass and metal that happened in the midst of other day-to-day events that did make news that day. For Tracey though, it was one of the most life-altering, profound experiences she has ever known. For those of us who are privileged in our work to come alongside young people who have suffered in some traumatic situation, music may prove to be a unique tool to open up new perspectives and insights as we gently guide them through the therapy process on the path of personal healing and development.

NOTE

Names and identifying details have been changed for the purposes of confidentiality.

REFERENCES

Alexander, D W (1999) Children changed by trauma–a healing guide. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition), Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

Bourne, E J (1995) The anxiety and phobia workbook (2nd Edition), Oakland: New Harbinger Publications

Gaston, E T (1968) Music in therapy. New York: Macmillan

Keen, A W (1989) Use of music as a group activity for long-term hospital patients. Social Work Practice. Issue 1, 4-6

Lewis, S (1999) An adult’s guide to Childhood Trauma–Understanding traumatised children in South Africa Claremont: David Philip Publishers

——— (2000) Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Treatment and Referral Guide. Compiled by the Scientific and Advisory Board Members of the Depression & Anxiety Support Group (SA), Johannesburg

——— (2000) Technical Manual: Child Functioning Inventories for Pre-, Primary and High School Children. Noordbrug: Perspective Training College Publications (E-mail: [email protected])

Alexander W. Keen is a Clinical Social Worker in Private Practice, South Africa.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Using Music as a Therapy Tool to Motivate Troubled Adolescents.” Keen, Alexander W. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 3/4, 2004, pp. 361-373; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 361-373. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].