Rehabilitation of the Wandering Seriously Mentally Ill (WSMI) Women: The Banyan Experience

SUMMARY. Started in 1993, in a small way, by a social worker as a response to the growing destitution of mentally ill women and with the objective of giving shelter, treatment and mainstreaming them, The Banyan has so far given ‘Adaikalam’ (refuge) to 413 women, of whom 252 have been rehabilitated. The entire care process starts from the time the women are picked from the streets in a disheveled and deranged state and brought to the home after much difficulty. On arrival they are spruced up and clinically assessed by a psychiatrist and put on medication. Slowly and steadily they return to the world of reality. Simultaneously, the inmates are put through various therapies like individual counseling, music, art, yoga, and vocational training. Finally, the address of the inmates is traced, and a team from The Banyan accompanies them, and they are rehabilitated. The family is enlightened about the illness, the woman’s stay at The Banyan, need for continuous medication. The Banyan is a lifetime service provider of medicines, keeping track by regular follow up and above all a friend to whom they can seek any help at any time. The role played by the social workers is so vital that the success of the programme hinges on their repertoire of skill and commitment. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. The Banyan, women, mentally ill, destitutes, rehabilitation, Nalini Rao, India

INDEX

Banyan: A huge tree with widespread branches supported by lateral roots. This tree is found in India and often finds mention in religious scripts as a benevolent tree giving succor and fulfilling the wishes of the devotee.

Adaikalam: A place where a person takes refuge.

India, the largest country in the Asian sub-continent, has inherited a rich civilization grounded in religion and philosophy. She has nurtured the cultural diversity of her vast landscape, which is reflected in her teeming millions. But, this hoary past has not ensured a comfortable present. Population explosion, poverty, illiteracy, new economic policy focusing on structural adjustments, the growing digital divide, and migration of people from rural to urban centers have initiated rapid social change. This has torn asunder the conventional social support configurations like value systems, the joint family norm, and neighborhood networks, making survival far from a pleasurable experience. These subsequently have had a deleterious effect on the psyche of the common man and much more, as explained below, on the women.

SHIFTING PARADIGMS–THE DOUBLE EDGED SWORD

When we look into the concepts of culture, gender, and health, it is indeed amazing to see the linkages between them, so intricately intermeshed and interdependent. Culture is a broad domain wherefrom constructs of gender and mental health draw their origin and sustenance. This is obvious and beyond debate. Gender does not merely indicate biological differences but is an essential part of the socio-cultural paradigm that has been painstakingly constructed and preserved over the centuries. The Indian society follows the patriarchal system of governance, where men are endowed with a lot of rights and privileges both legally and socially. Preference for sons, female feticide, girl-child marriage, and multiple pregnancies (resulting in fetal wastages and high maternal mortality rates) have resulted in low health status for women. Although there are several legal enactments since independence, focusing on enhancing the status of women in areas of inheritance, marriage, and education, how far they have been successfully implemented is questionable. Limited rights to property and education, battering, sexual exploitation and bride burning has had a cumulative toll on women.

The current globalization era not only symbolizes economic and technological development but also reflects a philosophy of life, de-layering the old for the new at every step. The merging geographical boundaries have unleashed change at an exponential rate. Women are not only major players in maintaining biodiversity and ecological balance; they are also the preservers of herbal medicine and seed conservation,9 but given the current context they are not able to live up to this critical role. Technological development has dismantled the village crafts. Mechanization of agriculture and other forms of production have raised the demand for skilled labour, thereby pushing women out of gainful employment, resulting in feminization of poverty, increase of women headed households due to desertion/widowhood, or migration of male population to cities.7 The modern women that we see in the media as informed, educated, decisive, assertive, and totally in control is an antithesis of the prevailing reality.

Although the relationship between globalization, mental distress, and high levels of vulnerability of women as a spillover of transition3 has been established, whether this has resulted in greater neglect and subsequent wandering away of the mentally ill women is yet to empirically established. “Increases in incidence of health and mental health problems, and of social disintegration within the families and communities, are anticipated results.”1 Nevertheless the growing number of vagrant mentally women has become a social issue and a public hazard.

MENTAL ILLNESS–THE BIG PICTURE

There has been no national mental health survey to date. But there have been several epidemiological studies conducted in different parts of the country at different points of time. Hence, the following data are the result of an extrapolation exercise. Conservative estimates place the national prevalence rate of mental illness at 73/1000 people (Urban rate at 73 and rural at 70.5–a difference of 2.5). Prevalence rate for all mental disorders in India is higher than Sri Lanka, but lesser than West Asian and African countries. The Indian urban rate is four times more than the median Asian rate. Schizophrenia occurrence is placed at 3.6 rural and 2.5 urban per 1000, and MDP at 37.4 and 33.7 (includes both psychotic and neurotic depression), respectively. Females have higher rates than males on an average of 1.5 times at the all India level. Women belong to the high-risk group. The vulnerable among them are the housewives with a prevalence rate of 104/1000, and among them, the married are even more susceptible, followed by widows. Statewise break down of urban prevalence rate of mental disorders shows Tamil Nadu, with an alarmingly high rate of 83/1000, 14% higher than the national figure and MDP at 43.3/1000, and schizophrenia at 2.5.

There are variations in a woman’s experience of mental illness/distress as she moves across different stages of her life cycle; it peaks during reproductive years, as demands on her are many, in terms of adjustment to her new roles and status as a wife, daughter-in-law, and mother (anger, disappointment and frustration that she may experience during this time find no avenues for release in a culturally approved manner) and tapers off during subsequent age periods. Although the prevalence rate is almost the same for both the sexes as far as severe mental disorders are concerned, there is a preponderance of male patients in terms of hospital admissions. This high percentage is due to ‘unconscious’ neglect of women based on feudal cultural values.3 Psychosocial factors pre-empt mentally ill women from accessing medical help. They are normally routed either to religious faith healers or are deserted/abandoned. But some do reach the level of GP consultation, and a few even access psychiatric help (mostly by default).

The current situation here is so typical of Ogburn’s ‘cultural lag’ theory, wherein he observes that material culture accumulates and religion, law, art, and custom replace rather than build on one another. He further asserts that material culture grows faster than adaptive culture, and hence modern society suffers from a great burden of unresolved social problems.6 Although there is legislation pertaining to mental health and National Institutes established with sophisticated treatment modalities, and societal attitudes, poverty, and family breakdown nullify all efforts. The Banyan, through its efforts, to a certain extent tries to bridge this lag.

The complex social issues are a spillover of rapid and haphazard economic development. Although the state emerged as a major service provider in the nineties, it was realized that the government was not competent enough, given its political and procedural constraints, to address the issue single-handedly. The adoption of the structural adjustment programmes saw declining investment in the health sector.5 When physical health is getting such a cursory treatment, mental health is not even mentioned in the overall health policy.

The National Mental Health Programme is limited in its implementation and out of focus. Both in the erstwhile Indian Lunacy Act (1912) and the more recent Mental Health Act (1987), there are provisions for the mentally ill persons who wander about without ostensible means of support (dubbed wandering lunatics by the 1912 Act), to be picked up by the police and produced before the nearest judicial court to receive orders for rehabilitation in the government and other approved hospitals. But the provision is only on paper. The police by and large ignore the deranged person on the street unless she proves to be a threat to the public. The need gap is to a certain extent taken care of by the non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These have the support of the local community, and they are more a response to the emerging needs of the people and have greater accountability and transparency.4 In this context ‘The Banyan’ is emerging more than a mere caretaker for WSMI (wandering seriously mentally ill) women in India.

THE ORIGIN

A deranged, half-naked woman living in her own world of delusions and hallucinations soon became an object of public taunts and ridicule and caught the attention of two young professionals: Vandana Gopikumar (Founder Trustee), a professionally qualified social worker; and Vaishnavi Jayakumar (Founder Trustee), a management student. They took her to established hospitals and welfare centers to admit her, but no one would admit her, as legal hurdles were quoted as an escape route. The burning desire to be of help to these women saw the beginnings of The Banyan–the roots were struck. That was in August 1993, seven years ago, and slowly the numbers grew, and the tiny sapling has now grown into a huge banyan tree–giving succor to hundreds of destitute mentally ill women in a home called Adaikalam, meaning refuge.

Starting a home for women who are suffering from an illness that is highly stigmatized is no mean task. The first step was to scout for premises to house these patients. People were contacted and after some search a house was finally selected, and the rent was borne by some well-wishers. This was just the beginning. There was lot of protests from the neighbors; it took some time to pacify them. Financial implications were high–mounting medical bills, transport costs, food, electricity charges, etc., meant more lobbying for funds from philanthropists and the general public and also for the cause of The Banyan.

PROFILE OF THE REHABILITATED WOMEN

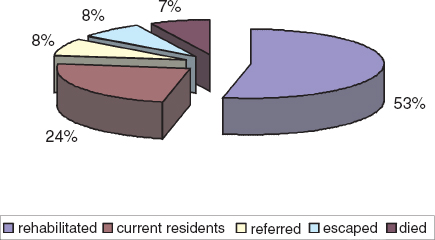

Records as of 30-05-2001 show that, of the total number of 473 beneficiaries that have taken refuge in the home since its inception, 112 are currently residents. A total of 38 beneficiaries have been referred to other organizations, over a period of time, as these women were mainly non-psychiatric destitute women picked from the streets, and 34 have expired due to secondary complications–in most cases, these women were long standing street wanderers who were not only mentally ill but were also afflicted with severe malnutrition/TB/diarrhoea/fever, etc. Those who escaped constitute the 37 and are grouped under ‘failures.’ 252 women have since been rehabilitated (see Figure 1).

Geographic Spread

A look at the map (see Figure 2) indicates the fact that the women have come from all parts of the country, even from distant states of Rajasthan and Punjab. But the majority of them (63 percent) seem to come from within the state of Tamil Nadu, where The Banyan is situated, followed by the neighboring state of Andhra Pradesh (12 percent). The rest have their origin from different states.

Area

Distribution of the residents indicates that most of the inmates come from the rural areas, followed by cities and towns. Of the total of 252, those who trace their origin to villages are 175, and 62 are from urban centers, and the remaining are from towns. There is a group labeled as ‘Not Known,’ a category referring to residents whose hometowns are yet to be identified. A multiplicity of factors, like high illiteracy rates, low nutritional status, less employment opportunities, and conservative norms of a village society make women from rural sectors more vulnerable to stress, as they find it difficult to overcome economic and psychological distress in a culturally determined context. Severe social control coupled with poverty pushes the women into the twilight zone of insanity, leading them away to strange lands and peoples.

Age

Figure 3 reflects the age distribution of the residents. Nearly 70% of the women belong to the 20-40 years age group, a critical and established age for the precipitation of psychotic disorders, especially for schizophrenia and manic depressive psychosis, a fact well established by earlier research findings the world over, when onset during these prime years leaves both the individual and the family totally devastated.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of Residents

FIGURE 2. Geographic Spread of the Rehabilitated Women

Marital Status

Married women succumb to various pressures. As already quoted earlier, married women also belong to the 20-40 years age group, when vulnerability to the illness is at the highest, as marriage entails adjustment to a stranger of a husband (most of the marriages in India are arranged by the elders in the family based on factors like caste, economic status, dowry–and compatibility between the two individuals does not find a place at all as a consideration for marriage), harassment by in-laws, physical and sexual abuse, pregnancies in quick succession, demand for a male child, deteriorating health, desertion by husband, polygamy, and low social status all have a cumulative effect on the mental health of the women. Of the total number of residents, 179 are married and 73 are either single or have been since deserted by their husbands.

Educational Status

Literacy levels are low; almost 50% of the rehabilitated are illiterate. Some of them have had school education up to primary level, and few of them have gone up to the secondary level. Three of them are post-graduates. The rest of them are illiterate, hailing mostly from the rural areas where educating girls is still looked upon as a luxury both in terms of financial implications and sparing a hand from farm labor/sibling responsibility.

FIGURE 3. Distribution of Rehabilitated Women–Age Wise

Economic Status

All of the women, except for a handful, come from families who belong to low economic strata, having incomes on an average less than Rs 3000 or $60 per month. Most of them hail from agrarian families, which are large in size. Fragmentation of land holdings, failure of monsoons, drought conditions, and heavy debt burden put these families within the vicious grip of poverty for generations to come. Even in the urban areas, most of them live off daily wages/petty business having irregular flow of finances, and computing income for a month is based on conjecture. Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend (1980) found that psychopathology was two and half times more in the lower classes than the upper class.8 This general pattern suggests that mental disorders are most likely to occur in disadvantaged sectors of society. However, the cause may be due to cumulative effects of environmental adversity or to selection process, or to some combination of social causation and selection. There is very little systematic information on the effectiveness of early outreach and treatment of childhood-onset or adolescent-onset disorder.2

Poverty and mental illness seem to act jointly to erase the ill-fated women’s self-identity and somehow make them undertake a random voyage to far-away places (for example, the distance from Rajasthan to Chennai is nearly 2000 miles). Such wanderings (impelled by some kind of accession of wanderlust which may be a part of the syndrome) seem to continue until they are stopped by a powerful, beneficial social force such as The Banyan, which seeks to reconstruct their past, their personality, and individuality and arranges for their return journey to their original abode.

Duration of Stay

The duration of stay at The Banyan varies from less than three months to more than three years. Although it is heartening to note that 40% of the inmates stayed less than three months, it is even more distressing that an equal percentage have stayed from six months to two years. Only 9% of the patients’ stay stretched beyond three years.

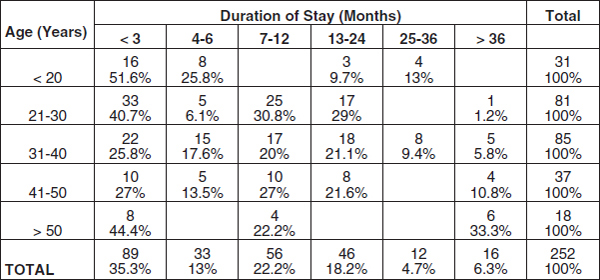

For long standing psychotics who stayed away from home for a lengthy period of time, tracing their families becomes a very challenging and arduous task. The younger the inmate, the shorter the stay. Nearly 87% of the less than 20 years age group was rehabilitated within six months. As the age increases, the residents’ stay spreads over a longer period. Although, of the 21-30 years age group, 50% successfully move out, nearly 44% stay on for nearly a year or two. The same applies to the subsequent two age groups ranging from 31-50 years. The duration of stay of inmates is even higher for those above 50 years (see Table 1).

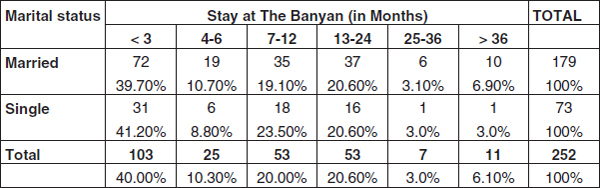

Table 2 indicates that the marital status of the individual does seem to influence the duration of stay. The married ones seem to stay on longer. There is the usual argument as to who should take the woman back. In many instances, it is between the husband who absolves himself of responsibility of taking care of her (unless there are grown up children in the family, who insist that they want their mother back) and the women’s natal family. The resolution of the tussle takes a while

REHABILITATION–THE QUALITATIVE PROCESS

The residents of The Banyan are literally picked up from the streets. Someone calls up or comes personally to inform about a ‘mad woman’ in their area, and immediately a social worker, along with one of the staff members, goes and after much cajoling and help from the members of the public brings her to Adaikalam. Simultaneously, the social worker informs in writing to the police officers on duty that the patient is being taken to The Banyan, and anyone seeking her can be directed to the home. Other legal formalities (though cumbersome) like procuring the reception order from the magistrate, a statutory requirement of the Mental Health Act, is also taken care of. Bringing her to the home is a herculean task by itself.

TABLE 1. Age and Duration of Stay

When she makes her first entry she is in a totally disheveled and deranged state with her body covered by grime and in a pitiable condition. At first her head is shaved carefully (lest the sores on the scalp bleed), as the unkempt hair is matted and infested with lice, then she is given a bath, dressed in a clean a set of clothes, fed, and examined by a consultant psychiatrist, diagnosed and put on medication, which usually comprises antipsychotic drugs, antidepressants, tranquilizers, and other supportive medication. They are also de-wormed, and tested for sexually transmitted diseases. Other secondary infections/diseases are also treated. Some of these women are pregnant when they arrive and are totally unaware of their delicate status. The team consists of a doctor, professional social worker, voluntary workers, and resident caretakers for each inmate for monitoring purposes.

The role of the social worker starts from bringing the patient home, informing the doctor, subsequent supervision, medication management, documenting the progress of the resident, and planning the rehabilitation strategy and accompanying them on their journey of reintegration. After due assessment of their psychosocial functioning and residual capabilities, all residents are put in any one of the following four groups.

TABLE 2. Marital Status and Duration of Stay

Group 4

This is meant for new entrants, for whom warmth, food, clothing, medicines, love, and affection become vital inputs to put them on the road to recovery. The social worker, with her professional zeal to help, is constantly in association with the patient and slowly but steadily establishes a rapport and a bonding that has a therapeutic effect on them. In the meantime medicines also do their wonderwork. Sometimes the patients are so violent and unpredictable, more so at this stage than others, that there are instances when the social workers and caretakers have been at the receiving end.

Group 3

This is for manageable and improving patients. During their stay at the home, which may range from one week to four years, the inmates are put through a series of psychosocial therapeutic techniques comprising individual and group counseling sessions. Once the inmates become oriented to reality, and they are able to establish some meaningful communication, they are able to relate better, and some crucial information is obtained from them. Everything gets recorded in their respective case files. The number of counseling sessions is determined by the chronicity of the illness, rate of recovery, personality of the inmate, education level, nativity, and other factors.

Group 2

The inmates progress. Slowly and steadily, the patients improve, drug dosages are altered accordingly, individual sessions continue, and the social worker becomes a pivotal and important person in the life of the inmate. Group sessions are planned and carried out by the social worker in the form of ADL (activities of daily living), exercises, yoga, aerobics, music and dance therapy. This helps them to develop interpersonal skills, and they form group affinity after several sessions.

Group 1

This group of residents is almost ready to return to their homes. They are now taught some vocational skills through workshops on candle making, greeting cards, block printing on napkins, table linen, basket making, threading flowers and making bouquets, etc. This acts both as a therapeutic exercise and also as a viable means of sustenance later on. They are entrusted with some housekeeping duties and also to take care of other residents. They are given an opportunity to attend meetings for a limited audience, to speak for their cause of inclusion.

Recreation includes outings to the beach, movies, celebrating festivals and sports, all of which, along with regular medication, love, and care, put these inmates slowly but surely on the road to recovery. Cultural differences of the residents are respected and maintained. Above all the dignity of the individual is upheld and nurtured.

THIS IS ONLY THE BEGINNING

Eliciting of information and tracing the address of the resident are both a rewarding and frustrating experience. Illiteracy, strange local dialects (residents come from all over India), inability to recall, and loss of contact with home makes case history construction an arduous and long drawn out process. Over several sessions, the social worker puts the bits and pieces of the puzzle together and finally a blurred picture emerges–life incidents, family constellation, name of hometown, and disjointed address. With this the search begins. Letters are sent out to the local post office/police station/school, depending on the clues given, and when there is a positive response from the other side then half the battle is won. Sometimes a member of the family comes to take her back resulting in a happy reunion.

Many a time there is no response. Efforts are then made to take the residents to their native place. The rehabilitative team led by the social worker selects a few of them, forming a homogenous group, those belonging to the same state or neighboring states based on certain reference points, like name, language, food habits, and way of dressing that they take to after improvement, and the vague address and landmarks that the resident often quotes, are grouped together. The date of journey is decided, and the team along with the residents leaves. It may be a month or more before the team returns.

They traverse thousands of miles by train/bus and even walk if it is to a remote village with just a single street and cannot be accessed by road. Sometimes the homes are traced without much difficulty, and the women are reunited. The family is educated about the illness, inmate’s stay, need for continuous medication and with an assurance that The Banyan is there for any other help if need be. Once the women are successfully reintegrated with their families, medicines are dispatched every month, and local doctors are identified and contacted for periodic review of the beneficiary.

There are instances when after a period of time the drug parcels return unaccepted either because the family has moved away to another town or village leaving no forwarding address, or the woman has wandered away/expired. There are also instances when the family brings back the woman as she has had a relapse or societal stigma is so high that they would rather not have her at home. In all these cases the Banyan once again takes them back into its fold … The role of The Banyan as not a mere transit home … but a lifetime service provider of medicines, follow up and above all a friend to whom they can seek any help at any time.

At times, for the other residents, after the long and arduous journey, the resident’s family is not traceable or there is a complete rejection of her and in a few such cases, there are instances when a local NGO, or a benevolent school teacher or the police came forward voluntarily as caretakers. At times, it turns out that it is not the resident’s hometown after all. In such situations, she is brought back once again to The Banyan, and she is helped to come out of her trauma of rejection/not finding her family. Specific skills are taught to her based on her interests, and she is sent for work in the neighborhood as a maid/flower seller/fruit vendor or in a small shop that stocks sweets, biscuits, pencils, stationery items, etc., so that she becomes economically independent. This process of mainstreaming is an essential part of The Banyan’s activities.

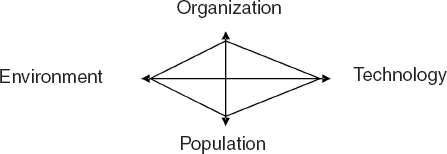

The Banyan’s useful endeavors give sociological significance under ecological perspectives theorized by Hauser and Duncan. This theoretical framework interrelates four aspects of the ecological complex, as illustrated below:

“The four sets of variables are in reciprocal relationship and the lines in the presentation above are meant to suggest the idea of functional interdependence.” Hauser and Duncan called it and ‘equilibrium-seeking’ system.

In the Banyan context, the population would be the composition of its inmates and the outside people it tries to reach out to; the organization would refer to the family and other institutions that at times fail to take care of the mentally ill, and as a result, consciously or unconsciously seek relief from the environment. They wander away from their original habitat and make their get-away in different directions. The technology that comes in handy for them is in the shape of transport–a long distance running train; overloaded with its passengers, it helps these women to remain unidentified and unnoticed. Here ecology of space meshes into the technology of transport.

The Banyan’s efforts become the equilibrium-seeking mechanism. Family’s failure and that of government agencies in providing relief to the destitute mental patients is made good by NGOs like The Banyan. The restoration of equilibrium is almost complete (a) when the government recognized and cooperated with The Banyan in setting up an office in its premises to give the official seal of approval for admission of inmates as per the act, and (b) when these women are reunited with their families.

It is ecological incongruity–a half naked woman in front of a prestigious educational institution in an upscale neighborhood–that sparked the starting of The Banyan, and it has over the years taken on the role of an ecological leveler.

It is almost ten years now since The Banyan was started, a long and tough journey, with miles still to go. But nevertheless there have been several bright spots that have brought cheer to the Banyan team. Several programmes are on the anvil, like starting a research wing, adopting neighborhood for community mental health programmes, and to identify like-minded individuals to start similar organizations in different parts of the country. But at the end of the day, the social work profession needs to gear up to the challenging demands of a society in transformation.

LANDMARKS IN THE HISTORY OF THE BANYAN–CELEBRATING LIFE

• August 1993–The Beginning.

• New Year–The first resident enters–Ms. Chellamal.*

• October 1994–Ms. Leela the first inmate to be rehabilitated

• End 1994–Media recognition–since then it has played a vital role in championing the cause of mental health and the Banyan.

• February 1995–Fund raising programmes a whooping success, the first of the series to follow.

• Mid 1995–Inauguration of community awareness programmes, followed by several over the years–talk shows, debates, contests, awareness walks.

• August 1996–Government grants six grounds of land to build a center.

• 1997–Formation of the Alliance for the mentally ill–volunteers of the Banyan, who help out from caring the residents, vocational training, fund-raising, rehabilitation, administration, etc.

• October 2000–Outreach programme is started to cover the neighboring rural village to spread awareness of mental illness and related issues.

• April 2001–Moving to a newly constructed three-floor center from small cramped house after a massive fund-raising drive, with contributions from the public, corporate houses, film stars, etc.

*Names of the residents mentioned are real.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. All Our Futures, Principles & Resources For Social Work Practice in a Global Era. Chathapuram S. Ramanathan & Rosemary J. Link. Wadsworth Publishing Company, USA. 1999.

2. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 200, 78(4), WHO International, 2000, Geneva.

3. Mental Health of Women, a Feminist Agenda. Bhargavi V. Davar, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 1999.

4. NGOs in The Changing Scenario. Meher C. Nanavatty, D. Kulkarni, Uppal Publishing House, New Delhi. 1998.

5. Social Impact of Social Reforms in India, P. R. Panchamukhi, Economic and Political Weekly, March 4, 2000.

6. Sociology an Introduction, Neil J. Smelser, Wiley Eastern Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi, 1970.

7. Women-Headed households. Coping with caste, class, and gender hierarchies. L. Lingam, Economic and Political Weekly, XXIX (12), 19 March.

8. World Health Organization-Report, Geneva, 1993.

9. Staying Alive, Women Ecology and Survival in India, V. Shiva, 2000.

10. Epidemiological Findings on Prevalence of Mental Disorders in India. H.C. Ganguli, 2000.

P. Nalini Rao is Lecturer, Madras School of Social Work, Chennai, India.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Rehabilitation of the Wandering Seriously Mentally Ill (WSMI) Women: The Banyan Experience.” Rao, P. Nalini. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 1/2, 2004, pp. 49-65; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 49-65. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].