Transforming the Legacies of Childhood Trauma in Couple and Family Therapy

SUMMARY. A multi-theoretical couple/family therapy clinical social work practice model synthesizes various social, family, trauma, and psychodynamic theories to inform a biopsychosocial assessment that guides clinical interventions. The client population involves adult partners who have negotiated the impact of childhood trauma, i.e., physical, sexual, and emotional abuses, including culturally sanctioned trauma. Couples may also be dealing with the aftermath of acute trauma related to interpersonal violence, political conflict, and/or the dislocations related to refugee or new immigrant status. Clinical examples demonstrate the usefulness of the model as well as contraindications when active physical violence is present. The construct of resilience remains a central focus in assessment and treatment. Specific attention to cultural and racial diversity enriches both assessment and treatment interventions with these high-risk couples and families. This practice model will be explicated in depth in an upcoming publication from Columbia University Press titled Transforming the Legacies of Trauma in Couple Therapy. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Childhood trauma, traumatology, couple therapy, clinical social work practice, complex post-traumatic syndrome

INTRODUCTION

This paper introduces a clinical social work practice model that synthesizes both social and psychological theories to assist high-risk couples and families who have negotiated the impact of childhood trauma. Attention is focused on the resilience of adult partners who have suffered childhood trauma (i.e., physical, emotional, and sexual abuses). Many clients live in multicultural urban U.S. cities, dealing with oppression due to racism, poverty, or discrimination that further compounds the legacies of childhood trauma. Clients in need may also be wrestling with the aftermath of acute trauma related to interpersonal violence, political conflict, and/or the dislocations due to refugee or new immigrant status (Mock, 1998; Walker, 1979). The disturbing political landscape of post-September 11 in the USA and the Iraq War adds even another layer of traumatizing events related to terrorist attacks and threats that have stirred major emotional upheaval for many families who are now coping with additional stressors. This range of health and mental problems affects all sectors of our society, demonstrating a vivid need for clinical social work services in a range of settings including family service agencies, mental health programs, outpatient and inpatient health facilities, and a range of community agencies.

This micro-couple/family therapy approach focuses on issues of power, control, attachment, and shame always within social context. Efforts are made to shift the “victim-victimizer-bystander” dynamic, which often permeates the relationships of trauma survivors (Herman, 1992). Faced with a daunting complexity of themes, this innovative clinical social work practice model draws from (1) social constructionist, feminist, and racial identity development theories to understand the social context; (2) intergenerational and narrative family theories to understand the family of origin influences; and (3) trauma, attachment, and object relations theories to understand the influence of trauma on an individual’s adaptation and inner world. This synthesis of social and psychological theories serves to inform a thorough biopsychosocial assessment that subsequently guides practice interventions.

Without question, legacies of childhood trauma often affect adult lives in both elusive and fairly direct manners. Although some trauma survivors approach their adult lives with unique zestful resilience, other adult survivors of childhood abuses experience difficulties in their capacities for attachment and intimacy (O’Connell & Higgins, 1994; Rutter, 1993). Pain and distress may occur not only on an internal or individual level, but also in interactions with other people, on the interactional level. Since many adults strive toward maintaining satisfying and productive partnerships, the majority of adult trauma survivors find themselves in relationships that require active work. In addition to issues of intimacy and control in decision-making in these partnerships, parenting also assumes primary importance for many survivors. Although some research studies suggest a low incidence of intergenerational transmission of abusive behaviors from parents who were abused as children, there is also a population of adult survivors who actively struggle to make use of the most effective, non-abusive methods of discipline with their children (Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; O’Connell & Higgins, 1994).

RATIONALE

In the midst of a current political climate in the United States that denigrates relationally based practice while overvaluing clinician productivity and rapid behaviorally defined progress, it is imperative that we continue to advocate for culturally sensitive, relationship based, theoretically grounded clinical social work practice. A question inevitably arises as to why a couple and family therapy approach with trauma survivors is important or even needed. In the field of traumatic stress, treatment has usually focussed on individual and group psychotherapy as well as psychopharmacology (Courtois, 1988; Krystal et al., 1996; Shapiro & Applegate, 2000; van der Kolk, 1996). Within the past two decades, feminist oriented clinicians have also facilitated empowerment models with psychoeducational support to partners and families (Bass & Davis, 1988; Gil, 1992). More recently, the use of cognitive-behavioral interventions such as eye movement desensensitization reprocessing (EMDR) and dialectical behavior therapy have been popular and useful models for some clients (Compton & Follette, 1998). Yet, once again, the primary therapy goals involve the remediation of individual aftereffects of trauma.

Another central question emerges: What effects do traumatic experiences of childhood have on adult partnerships and family interactions? Aftereffects of childhood trauma do not restrict themselves solely to the individual. In fact, family members are not only affected by the legacies of childhood trauma; they also influence, both positively and negatively, the survivor’s experience. And so, it is important to pay attention to couple and family therapy with adult survivors of childhood trauma that relies on social, psychological, and neurobiological theories to shed clarity on the sociocultural, interactional, and individual influences within the couple (Basham & Miehls, 1998).

Although I refer to family as well as couple therapy practice, the unit of focus is actually the couple whose presenting issues may range from parenting concerns, relationship ruptures, conflict around roles and responsibilities, communication problems, sex and intimacy, financial strains, adaptation to a new culture, or spiritual ennui. If active physical violence exists, then an advocacy approach is recommended while couple/family therapy is contraindicated. With such a wide spectrum of concerns, it is useful to rely upon a range of psychological and social theories to assess a couple from different perspectives. Changes in the couple’s capacities and needs may also call for continuing flexibility from the clinician in formulating assessments and treatment plans.

There are many integrative couple and family therapy models that aim to incorporate parts into a whole. However, since the process of integration involves a blending or melding of constructs, the notion of synthesis seems more useful. Synthesis involves combining discrete and, at times, contradictory constructs into a unified entity. Such an approach has usually been equated with eclecticism, an often devalued approach in social work. Negative stereotypes are often needlessly hurled at practitioners who weather accusations of randomly constructing a potpourri of unassimilated theoretical constructs. A more accurate definition of eclecticism refers to a choice of the best elements of all systems. Still, this definition differs from synthesis, which aims to build a unified plan with disparate constructs. A serendipitous benefit of a synthetic practice model is the high value placed on flexibility with different lenses to understand the uniqueness of each client. The use of metaphor is helpful in describing this synthetic stance. If you visualize staring at a crystal, the texture and color look different depending on what part of the multi-faceted crystal you are observing. Similarly, the fabric of this theoretical synthesis may shift color and shape over time during the course of different phases of the couple therapy.

In a similar fashion, a case specific practice model changes the synthesis of theoretical models depending on the unique features and needs assessed for each couple. Therefore, the assessment and therapy process sustains a continuing dynamic flow of theory models that advance to the foreground while other theoretical models remain in place, momentarily, in the background. This phase-oriented couple therapy model attends differentially to the centrality of the presenting issues. Important decision-tree processes occur at the point of initial contact with the couple, during the assessment phase, and during the phases of treatment. Although a range of social and psychological theories are available in the knowledge base of the clinician at any given moment, data forthcoming from the couple’s presenting concerns determine which set of theoretical lenses advance to the foreground.

Certain theoretical models are used from the onset of therapy. For example, since a relationship base provides the foundation to the practice model, it is essential to understand relationship patterns through the lenses of object relations, attachment, and relational theories (Kudler, Blank, & Krupnick, 2000). In addition, social constructionist, racial identity and feminist theories shed clarity on the family’s social context (Manson, 1997; Marsella, Friedman, Gerrity & Scurfield, 1996; Pouissant & Alexander, 2000). As a couple reveals their shared narrative, the presenting issues further signal which theoretical approaches may be especially relevant. Stated concerns about social interactions relating call for the use of an historical family perspective to explore family patterns, family rituals, and family paradigms. A narrative family perspective may also illuminate the multiple unique meanings of the trauma narrative (Sheinberg & Frankael, 2001; Trepper & Barrett, 1989; White & Epston, 1990). Symptoms of clinical depression may signal the need to employ a cognitive-behavioral lens to explore affect regulation and cognitive distortions. In general, a review of the cognitive, affective, and behavioral functioning of each partner also addresses mastery, coping, and adaptation (Compton & Follette, 1998). Finally, in the individual arena, trauma theories focus on the short- and long-term neurophysiological effects of trauma on brain function, particular memory and affect regulation (Krystal et al., 1996; Schore, 2001; van der Kolk, 1996). Although an assessment of each partner’s trauma history is necessary in all cases, trauma theory may recede in centrality if there is an absence of trauma. However, in those situations where one or both partners suffered trauma in childhood or adult life, trauma theory should remain one of the central theoretical lenses situated in the foreground of couple therapy. In particular case situations, it becomes clear how all of the social and psychological theory lenses are present concurrently from the onset and throughout the course of therapy. However, one or more theoretical lenses may advance to the foreground in the therapy, when that perspective may be relevant to a particular presenting issue at hand.

In summary, the synthesis of biological, social, and psychological theory models informs the biopsychosocial assessment that subsequently guides the direction of practice. Holding the tension of multiple, often contradictory theoretical perspectives requires flexibility in perception, understanding, and action on the part of the clinician. Knowledgeability about these varied models and perceptiveness are also essential requirements to sustain this both ephemeral and solid stance.

DEFINITIONS AND DEMOGRAPHICS

Before proceeding further with a discussion of this synthetic practice model, the construct of trauma needs to be defined. Although social constructionists posit that the concept of trauma is relative, based on the sociocultural context at the time, this fluid definition points to the range of meanings offered by researchers and clinicians in their assessments of trauma.

Constructs of Trauma

Figley’s (1987) definition is useful in a general way. He refers to trauma as “an emotional state of discomfort and stress resulting from memories of an extraordinary, catastrophic experience which shatters the survivor’s sense of invulnerability to harm.” Herman (1992) discusses how trauma overwhelms an ordinary system of care that gives people a sense of control, connection, and meaning in the world. Allen (1998) and Pinderhughes (1998) assert that the day-to-day racist assaults inflicted on people of color perpetuate the legacies of slavery and colonization. In addition, they believe strongly that such racist practices should also qualify as chronic repetitive trauma. For example, the cultural devastation resulting from the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII and disenfranchisement of indigenous peoples in the U.S. qualify as other examples of culturally sanctioned trauma (Daniel, 1994).

This couple/family therapy practice model focuses primarily on Type II trauma, generally defined as sequelae of childhood sexual, physical, and emotional abuses that includes chronic, repetitive, culturally-sanctioned trauma (Herman, 1992; Terr, 1999). In order to clarify the definitions of Type I and Type II trauma, Terr distinguishes the effects of a single traumatic blow, which she calls Type I trauma, as compared with the effects of prolonged, repeated trauma, which she calls Type II trauma. Regrettably, many survivors of childhood trauma also experience discrete Type I trauma (such as an accident, assault, or natural disaster) or repetitive Type II traumas (such as domestic violence) in adult life as well. And so, a clinician must be mindful of the effects of both Type I and Type II trauma. The severity of effects of trauma depends on five factors. They are (1) the degree of violence, (2) the degree of physical violation, (3) the duration and frequency of abuse, (4) the relationship of the victim to the offender, and (5) the age at which trauma occurs (Terr, 1999). When trauma intrudes during infancy, the emergence of basic trust, a sense of cohesive identity, and secure attachment are undermined. However, if trauma occurs after a child has developed a sense of cohesive self with object constancy, the aftereffects may or may not involve the full constellation of complex PTSD symptomatology, which involves alterations to identity.

Cultural Relativity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Exploration of the effects of trauma raises the controversy surrounding the increasing popularity of the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as outlined in the widely used diagnostic classification system to understand emotional conditions and mental disorders, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Before discussing the cultural critique, an explication of the diagnosis should first be introduced. Posttraumatic stress disorder is:

a syndrome that occurs after a person has been exposed to a traumatic event in which the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others. In addition, the person’s response involved intense fear, helplessness or horror. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in one or more of the following ways: (1) recurrent and intrusive distressing recollections of the event, including images, thoughts or perceptions; (2) recurrent distressing dreams of the event; (3) acting or feeling as if the traumatic event were recurring (includes the sense of reliving the experience, illusions, hallucinations and dissociative flashback episodes, including those that occur on awakening or when intoxicated); (4) intense psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event. There is also persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness (not present before the trauma), as indicated by three (or more) of the following: (1) efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings or conversations associated with the trauma; (2) efforts to avoid activities, places, or people that arouse recollections of the trauma; (3) inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma; (4) markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities; (5) feeling of detachment or estrangement from others; (6) restricted range of affect, e.g., unable to have loving feelings and (7) sense of a foreshortened future, e.g., does not expect to have a career, marriage, children or a normal life span. There are also persistent symptoms of arousal (not present before the trauma) as indicated by two (or more) of the following: (1) difficulty falling or staying asleep; (2) irritability or outbursts of anger; (3) difficulty concentrating; (4) hypervigilance; and (5) exaggerated startle response. The duration of the disturbance must be longer than one month; if the duration is less than three months, the situation is acute while a chronic state occurs when the symptoms persist beyond three months. (DSM-IV)

Although the heuristic nosology of a PTSD diagnosis provides a useful way of understanding the impact of trauma in diverse cultural groups, the culture-boundedness of the model limits a universal generalizability (Friedman & Marsella, 1996; Mock, 1998). An interesting research project revealed that the majority of African Americans interviewed are highly resilient and do not suffer PTSD (Allen, 1998). In contrast, a number of recent studies suggest that children who live in violent communities are at higher risk for developing PTSD symptomatology (McCloskey & Walker, 2000).

Another intriguing project launched by Becker (1999) and his colleagues at Yale explored the adaptation of Bosnian adolescent refugees who fled to the U.S. They found that many of the adolescents did not develop PTSD symptoms and, when they did, their recovery was more rapid as compared with their parents. Treatment recommendations focused on strengthening the entire family unit, as opposed to an exclusive focus on the individual, since the adaptation of the parents was a predictor for the effective adaptation of adolescents (Gibson, 1999). In this case, the cultural relativity of the diagnosis of PTSD bore fruitful discussion.

Judith Zur (1996) conducted a research study that explored perceptions of the Quiche, a group of indigenous Guatemalans, of their experiences during their Civil War. Since this conflict involved genocidal activity, a Western viewpoint might predict PTSD syndrome among survivors. This researcher points out the absence of social context in assessing PTSD and concentrates on two elements of social context. First is the Quiches’ interpretation of agency and belief in fate as causal factors for violence. Such a stance relieves the offenders of any responsibility for their actions. Second is their understanding of emotions, which involves a valuation of emotional restraint. Since overt grief is only tolerated for nine days as a cultural proscription, families experience the ongoing loss of their loved ones as an economic, rather than a personal, loss. Finally, disturbing dreams, which could be viewed as PTSD symptomatology, can be relieving for the Quiches since such distressing dreams are considered valuable portents from the dead. Although these trauma survivors suffered from political genocide, these research data suggest the importance of evaluating the cultural meanings of trauma-related phenomena before recommending a treatment regimen for PTSD.

Demographic Data

As this paper is embedded in a sociocultural perspective, it is important to share the alarming demographics regarding childhood trauma in the U.S. In 1996, the third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect based on reporting from Child Protective Services revealed substantial increases in the incidence of child abuse and neglect as compared with the data gathered from the last national study, completed ten years earlier (Sedlak & Broadhurst, 1996). Rates of physical abuse nearly doubled; sexual abuse more than doubled; and emotional abuse and neglect rated two-and-one-half times earlier levels. There were no significant differences according to race. However, children from the lowest income families were eighteen times more likely to be sexually abused, almost fifty-six times more likely to be educationally neglected, and twenty-two times more likely to be seriously abused by child maltreatment or neglect as compared with children from higher income families. Sexual abuse of girls occurs three times more often than it does for boys.

Current data, although underreported, suggest that 35% of adult women report intrafamilial sexual childhood abuse, most frequently between the ages of seven and twelve. A smaller percentage (20%) of adult men reports childhood sexual abuse, often extrafamilial in nature, frequently, but not exclusively, from male friends, teachers, or coaches. Again, these data for male abuse survivors are dramatically underreported due to fears of disclosure in a homophobic environment. In any event, the increasing incidence of reports of child maltreatment is quite alarming. As these children grow to adulthood, a few fortunate individuals will emerge unscathed, while many others may wrestle with trauma-related aftereffects in their adult lives. If they partner, then trauma-related issues may arise in parenting, family dynamics, and their intimate relationship.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE

In order to explicate this model as more “experience-near” for the reader, the following clinical vignette is introduced. (All names and identities are disguised to protect the privacy of the clients.) Rod and Yolanda Johnson, an African American couple, each in their early forties, both working full-time in technical jobs, sought help following the recent adoption of an eighteen-month-old daughter, the offspring of an extended family member. (The identities of this family have been disguised; all names are changed to protect privacy.) I met with this couple for a total of 20 therapy sessions over a six month time period. After a sixteen-year marriage with a history of two miscarriages and one stillbirth of a baby daughter, Rod and Yolanda worried about potential divorce. Yolanda called to complain about Rod’s “lack of involvement,” her “floods of tears,” and “constant verbal fights.” Both partners completed high school and worked reliably at their respective jobs. Although both were reared in alcoholic families, neither currently drank alcohol. At the point of seeking help, they were engaged in vicious verbal battles constantly and considered divorce. Yolanda initiated the first telephone call at the urging of her friend, who had met with me and her husband to successfully work out issues in their marriage. Noteworthy strengths for this couple included a strong sense of responsibility to family and work, religious beliefs, sobriety, durability of a sixteen-year marriage, and loving connections with family and friends.

Developmental Histories

Yolanda, as the oldest of six children, was recruited early on to help out with younger siblings, developing caregiving skills which became a source of pride and accomplishment. When Yolanda was six years old, her father’s drinking worsened. He yelled and beat her and her siblings with hangers and belts. Yolanda recalls trying to withhold her tears, yet winced when she saw her bloody scars afterwards. After also enduring sexual abuse between ages eleven and fourteen, perpetrated by an uncle, she learned to appease both her father and uncle by working as hard as hard as she could. No one believed her reports of abuse when she told an aunt and grandmother. Yolanda’s exceptional school performance and her endearing personality won her accolades. Life in a primarily middle-class African American community shielded Yolanda from persistent racist attacks, however, she was acutely aware of covert racism in school and in her community.

Rod, as the third of four children, struggled with poverty and violence from his alcoholic father. He describes his father as embittered and destructive, often arriving home to greet the children after school with yelling and cursing. When frustrations mounted, he erupted by beating Rod and his brothers. At the age of eighteen, after finishing high school, Rod struck back and was banished from home, venturing north to establish a new life. Rod was shocked to note that the harsh racial insults that he had suffered during a segregated pre-Civil Rights era South occurred with frequency in the North as well. At the onset of couple therapy, Rod was completely estranged from his family of origin. In spite of some of the education and socioeconomic differences between Rod and Yolanda, and their respective histories of childhood trauma, the commonalties of mutual respect, work responsibility, loyalty to family, and shared dreams provided a strong foundation to their currently beleaguered sixteen-year marriage.

Biopsychosocial Assessment

Since each couple is unique and complex, it is necessary to engage a couple in a thorough biopsychosocial assessment that guides careful decision-making regarding sequencing and choices of practice interventions. Each clinician is urged to identify both strengths as well as possible vulnerabilities in each of the sections of the assessment outline, i.e., the sociocultural, interactional and individual (see Figure 1).

Sociocultural Factors

First, a review of sociocultural factors notes how the influences of extended family, community, the agency context, and the political climate may exacerbate or mediate the aftereffects of trauma. Relevant diversity themes (i.e., race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, and disability) also require a central focus as they affect both the incidence and aftereffects of childhood trauma (Kersky & Miller, 1996).

FIGURE 1. Biopsychosocial Assessment in Couple/Family Therapy with Survivors of Childhood Trauma (Physical, Sexual, and/or Emotional Abuse)

Countertransference and Use of Self

Not only must a clinician be mindful of countertransference responses but she should also be aware of the impact of vicarious traumatization and re-traumatization (Chu, 1992; Francis, 1997; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995). There are a number of predictable countertransference traps in practice with trauma survivors. Since many trauma survivors possess an internalized relational template that involves the victim-victimizer-bystander pattern, this drama may be regularly externalized through projective identification (Miller, 1994; Herman, 1992). Projective identification is a psychological process where each partner represses, splits off, and projects onto the partner an aspect of the internal dispute that is disowned (Ogden, 1991). What is fought out are the conflicts that neither partner has been able to address internally. As a result, each partner may engage the other as well as the clinician in these projective identification dances. Of course, the clinician’s unresolved personal issues factor into this equation as well. For example, the first potential countertransference trap involves slipping into a passive and indifferent bystander stance that mirrors the couple’s numbness and detachment. Another trap leads to helpless victimization, or not knowing how to proceed. A rescuer theme may also be elicited in couple therapy, where the clinician finds herself extending the boundaries of sessions, losing clarity around professional role and financial compensation, or generally trying to become the quintessential omnipotent rescuer. An eroticized countertransference trap is common as well, where a range of sexualized feelings may be activated toward either partner. Caution is recommended to avoid eroticized reenactments that recapitulate the earlier childhood traumas. Behaving aggressively may be another countertransference enactment where the clinician disavows anger and behaves in a false, overly solicitous manner. In summary, enactments on the part of the clinician are inevitable. However, it is essential that the clinician understand the nature of these countertransference enactments in order to strengthen an empathic connection with the client and to minimize the occurrence of these missteps as best as possible in order to facilitate positive changes.

Now that certain sociocultural influences have been addressed in a general fashion, the specific sociocultural influences facing Rod and Yolanda are introduced. Various questions are posed to explore the nature of these forces. For example, what is the role of each partner’s extended family? Community? Agency context? Clinician biases? Sociopolitical attitudes? How do diversity themes affect the adaptation of this couple? Since various diversity themes mediate the impact of trauma, which themes are most central?

Initially, Yolanda stated that Rod had no interest in therapy since it was “only for crazy people” and that he “disliked white people.” Several questions emerged at this point. Was this assertion an expression of Yolanda’s ambivalence about cross-racial therapy as well as Rod’s? And, was Rod completely unreceptive to seeking therapy? In order to establish an alliance with Rod, I asked Yolanda if he might call me. When Yolanda rejected this plan, I offered to call Rod directly so that I would be able to hear his thoughts about the situation. After Yolanda reluctantly claimed that Rod would immediately resist any conversation, I proceeded to talk with Rod, who aired his concerns and decided to meet for one couple therapy session. He stated that it was “less shameful” to meet with a Caucasian clinician who was unrelated to his community. And so, is this tentativeness an expected “culturally congruent paranoia” understandable in cross-cultural therapy (Grier & Cobbs, 1968)? Do the couple’s attitudes reflect internalized racism in choosing a clinician from the dominant culture? Or, are they choosing the clinician based on positive transference and expertise in the field? As the clinician, are there potential countertransference traps related to overly zealous “culturally-competent” rescuing tendencies? Perhaps all of these speculations require some consideration.

In summary, the Johnson couple presented race and gender as central themes that permeate their daily lives. Stereotypic gender roles influenced each partner’s expectations about how they should behave as partners and parents. Their estrangement from church as a major historical source of support currently undermines their foundation in the family. Although allegiance to family and a work ethic fortify this couple, the sociocultural pressures and historical legacies impose negativity and failure that undermines a focus on strength in their capacities.

Interactional Factors

The interactional factors that are especially relevant to survivors of childhood trauma include the interplay of the victim-victimizer-bystander paradigm, trust, intimacy, power and control, communication, sexuality, and boundaries (Miller, 1994). Since survivors of childhood trauma have been subjected to abuses of power from adults designated as their caregivers, such violations set the stage for a sense of betrayal and distrust. Subsequently, these individuals find themselves in relationships during adulthood where the dynamics of a victim-victimizer-bystander pattern are reenacted in adult life. Not only might a survivor relate to other people with this pattern, she also internalizes a victim-victimizer-bystander template that guides a vision of the world. Once again, it must be clear that a victim of violence should not be held responsible for activating violent treatment, even if this dynamic pattern operates.

For Rod and Yolanda Johnson, the victim-victimizer-bystander was pronounced. Rod and Yolanda continuously battled for control, with Yolanda presenting herself as emotionally responsive while Rod prided himself on emotional containment. Yolanda viewed herself as over-responsible and Rod as under-responsible. He, on the other hand, viewed himself as more relaxed and spontaneous. Rod often felt persecuted by Yolanda, complaining that she failed to understand him and withheld sex. Yolanda rejected the notion that she was abusive, feeling justified in her attacks. Yolanda, herself, felt victimized by what she viewed as Rod’s casual withdrawal as the neglectful bystander and the victimizer who abandoned her to do all childcare and housework. And so the victim-victimizer-bystander dynamic played back and forth, with Rod and Yolanda assuming all three roles. This alternating yearning for connection mixed with a fear of loss and violation fuels a pattern of shifting victimization. These unrelenting polarized fights always remained verbal, pointing out a noteworthy strength for this couple in their avoidance of physical altercations. Cross-racial therapy introduced additional layers of complexity to this dynamic as well, where I was viewed alternately as the wished for rescuer-bystander, the feared victimizer, or the helpless victim.

Individual Factors

Now that interactional factors have been explored, the individual factors and the inner world need to be assessed as well. Important influences include the neurophysiological effects of trauma including PTSD or complex PTSD symptomatology (Dansky et al., 1996; Krystal et al., 1996; Shapiro & Applegate, 2000; van der Kolk, 1996). For example, the presence of flashbacks, arousal vs. numbness phenomena, and affective instability are included. Intrapersonal factors focus on each partner’s object relational and attachment capacities as well as the role of projective identification.

A return to the clinical vignette reveals that the neurophysiological symptomatology of PTSD influences Rod and Yolanda. Although Rod does not suffer acute physiological symptoms, he does, in fact, respond abruptly to touch, demonstrating stimulus barrier issues that affect intimacy. His periodic drinking reflects some effort to modulate his hyperarousal pendulum. Otherwise, the primary aftereffect of Rod’s physical childhood trauma, compounded by racialized assaults, has been damage to his self-esteem. Yolanda takes reasonable care of her physical health, but is plagued with depression. She also suffers a startle response, dislikes surprises, and experiences touch as painful. Antidepressant medications, journal writing, meditation exercises, and cognitive-behavioral techniques to regulate affect were all useful methods to reduce these problematic symptoms of complex posttraumatic syndrome.

Persistent issues with diminished self-esteem remained for both partners. While exploring Rod and Yolanda’s inner worlds, projective identification processes unfolded vividly. In this adaptive defensive process, the person who projects an internal, disavowed conflict onto the other person engages the other in an externalized drama where both partners fight overtly over the issue (Scharff & Scharff, 1987). A critical reminder here is that no matter how a partner behaves toward others with inciting projections, each person is held responsible for managing their anger appropriately. There is no excuse or sanction for violence. Typically, Rod projected his internal conflicts surrounding a wish for affirmation countered by experiences of punishing abuse, activating Yolanda’s verbal persecution and victimization of him. Her acute criticalness usually followed experiences where Rod failed to follow through on promises. Yolanda disowns her own internal conflict surrounding her dependency needs. For example, she yearns for a loving connection, yet anticipates abandonment, and ultimately behaves in ways that precipitates Rod’s withdrawal. With reasonably sound object relational and attachment capacities in place, Rod and Yolanda could bear the emotional intensity involved in the clarification of these projective identification processes. As they recognized the tenacious cycle of emotional victimization and oppression, they were better able to interrupt this destructive cycle. In summary, the sociocultural/institutional, interactional, and intrapersonal factors comprised a thorough bio-psychosocial assessment of Yolanda and Rod’s couple dynamic that guided the development of a couple therapy plan. Before the actual therapy course for Yolanda and Rod is described, some general guidelines for this phase oriented practice model will first be introduced.

PHASE ORIENTED COUPLE THERAPY PRACTICE MODEL

In spite of the creative variability that enters into each individual case assessment, there are some general guidelines that are useful for all biopsychosocial assessments and decision-making regarding the sequencing and choice of interventions. Overall, this couple therapy practice model functions as a phase model that parallels contemporary individual and group psychotherapy stage models with trauma survivors (Courtois, 1988; Figley, 1987; Gelinas, 1995; Herman, 1992; Miller, 1994; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995). However, there are distinct commonalties and differences between these models. In general, stages are similar to phases in terms of identifying certain uniform challenges, yet traditional stage models presume essential sequential development. On the other hand, this approach expects that diverse themes may be revisited at different periods throughout the work. The metaphoric image of a three-dimensional triple helix comes to mind here with the weaving together and interconnections of various themes.

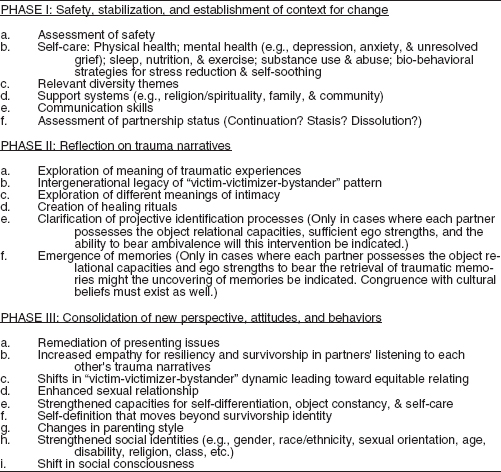

The phases of couple therapy include Phase I: Safety, stabilization, and the establishment of context for change; Phase II: Reflection on the trauma narrative; and Phase III: Consolidation of new perspectives (see Figure 2). Phase I (Safety and stabilization) tasks are relevant for most, if not all traumatized couples in therapy. Here, it is essential to determine if the couple has secured basic safety in terms of food, shelter, and freedom from physical or external violence. As mentioned earlier, an advocacy role is assumed to ensure safety for a victim if physical violence is detected. A couple therapy modality is contraindicated at such times since it often inflames an incendiary dynamic. Assessment of self-care is strengthened by psychoeducational support about PTSD and complex PTSD symptomatology.

After reviewing the safety of the external environment along with efficacy of self-care, the clinician then needs to assess the extent of interpersonal supports among family, friends, and colleagues. The nature of community and spiritual community supports is explored here as well. In general, this phase involves a full range of psychoeducational, cognitive-behavioral, body-mind, spiritual, and ego supportive interventions that promote adaptation and coping.

Many couples are content to end their therapeutic work after completing Phase I tasks, having resolved their basic presenting issues. An important point to stress is that we, as clinicians, often overvalue the uncovering of traumatic memories. Even when couples have the object relational capacities to explore insight oriented work, they may decide to end their work after having grown from the range of Phase I ego-supportive interventions. Such cognitive-behavioral changes can positively influence a couple over a sustained period and can readily be accomplished within a brief time frame. Many couples may move along to Phase II work, which involves a reflection upon the trauma narrative. However, it is not necessary for all couples to follow such a therapy course in order to establish new more equitable ways of relating.

FIGURE 2. Phase-Oriented Couple Therapy with Survivors of Childhood Trauma: Treatment Phases

Phase II: Reflection on Trauma Narratives

Phase II involves sharing original perspectives on the childhood trauma experiences while restorying the narrative with a new focus on resiliency and adaptation. Since there has been so much controversy about the alleged benefit of uncovering traumatic memories, most couples benefit, instead, from a reflective sharing of their childhood trauma memories without full affective reexperiencing. Instead, an integration of affect, cognition, and memory become the therapy goals. In addition, increased capacity for empathic attunement often occurs during this sharing of experiences.

Congruence with sociocultural influences may also determine the usefulness of uncovering traumatic memories. If such a path promotes flooding or decompensation, uncovering work is contraindicated, especially when there are cultural prohibitions against such catharsis. For example, with one of my refugee couples from a war-torn Central American country, each partner had suffered torture and imprisonment from caregivers and prison guards during their respective childhoods. Cultural, religious, and political forces joined together to create a worldview that valued containment while devaluing expressiveness of intense affect. In this case, a cognitive reflection on the victim-victimizer-bystander dynamic helped this couple; retrieval of memories was clearly contraindicated. Finally, object relational capacities also determine efficacy of uncovering traumatic memories. If partners have not yet attained object constancy and lack the capacity to tolerate ambivalence in intimate relationships, then once again, uncovering of traumatic memories is not indicated.

An important point to revisit is that as clinical social workers, we continue to overvalue the uncovering of traumatic memories under the guise of an insight-oriented psychotherapy frame. Even when cultural congruence and object relational capacities exist, it remains preferable to focus on safety and stabilization work if the couple reports reasonable satisfaction with progress. If continued work is indicated, phase II tasks then focus on the reflection on and restorying of the trauma narrative.

Phase III: Consolidation of New Perspectives

Phase III involves a focus on family of origin work along with strengthening family and community relationships. Couples at this point report less shame, stigma, and isolation. They often move beyond self-definitions as survivors to overcomers or thrivers. While parenting becomes less problematic, couples may also express a greater sense of mastery, vitality, and joy. Resolution of the tasks undertaken during these phases of couple therapy does not follow a sequential developmental line. Instead, a more realistic path involves a revisiting of different phases throughout the course of the work.

EVALUATION OF COUPLE THERAPY PRACTICE WITH YOLANDA AND ROD JOHNSON

In summary, Rod and Yolanda Johnson progressed steadily in their couple therapy. In the first six weeks, goals focused on the abatement of depression for Yolanda, resolution of the decision to work on the marriage rather than divorce, reduction in arguments, improvement in communication effectiveness, and enhanced understanding and self-care around complex PTSD symptomatology. As this couple proceeded to work on their relationship for the remaining three months, the focus shifted to exploring their different meanings of intimacy, the intergenerational origin of the victim-victimizer-bystander patterns, and the heart wrenching grieving for their lost children. Only after they grieved the losses of three children thorough miscarriage and a stillbirth were they emotionally freed to embrace their new adopted daughter. Since the Johnsons experienced reasonable stability and safety in their family environment and had the object relational capacities to tolerate conflict and ambivalence, they were able to reflect upon their histories of childhood abuse. As each partner shared their childhood memories, they were able to integrate a focus on their strengths and resilience in the face of adversity. Each partner was able to reflect upon the origin family and re-story their roles from victim to survivor to pioneer while sharing these reminiscences. Empathy was strengthened while their emotional and sexual relationship became more mutual and less hierarchical. As they recognized how their victim-victimizer-bystander dynamic mirrored not only their abusive childhood homes but also societal racist patterns, they expressed relief from internalized racial oppression as well as the oppression of their trauma histories.

In summary, this paper has attempted to provide an overview of this synthetic couple/family practice model with adult survivors of childhood trauma that is firmly grounded in a synthesis of social and psychological theories. Hopefully, this presentation has conveyed both the complexity and uniqueness of each couple in their impressive, oftentimes ambitious, endeavors to transform their historical legacies in positive ways. This clinical social work practice approach may be useful for the many couples and families who seek help in health, family service, or mental health settings in the months and years ahead.

Allen, I. (1996). PTSD among African Americans. In A. Marsella, M. Friedman, E. Gerrity & R. Scurfield (Eds.), Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research and clinical implications. (pp. 209-238). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2001). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition). Washington DC

Basham, K., & Miehls, D. (1998). Integration of object relations theory and trauma theory in couple therapy with survivors of childhood trauma. Part I. Theoretical formulations. Part II. Clinical illustrations. Journal of Analytic Social Work 5(3), 51-78.

Bass, E., & Davis, L. (1988). The courage to heal: A guide for women survivors of child sexual abuse. New York: Harper & Row.

Becker, D., Weine, S., Vojvoda, D., & McGlashan, T. (1999). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(6), 775-781.

Chu, J. (1992). Ten traps for therapists in the treatment of trauma survivors. Dissociation, 1-18.

Compton, J., & Follette, V. (1998). Couples surviving trauma: Issues and interventions. In V. Follette, J. Ruzek, & F. Abueg (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral therapies for trauma. New York: Guilford Press.

Courtois, C. (1988). Healing the incest wound: Adult survivors in therapy. New York: Norton.

Daniel, J. (1994). Exclusion and emphasis refrained as a matter of ethics. Ethics and Behavior, 4(3), 229-235.

Dansky, B., Brady, K., Saladin, M., Killeen, T., Becker, S., & Roitzsch, J. (1996). Victimization and PTSD in individuals with substance use disorders: Gender and racial differences. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 77(1), 75-93.

Figley, C. (1987). A five-phase treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in families. Journal of Traumatic Stress, (1), 127-141.

Francis, C. (1997). Countertransference with abusive couples. In M. Solomon & J. Siegel (Eds.), Countertransference in couples therapy (pp. 218-237). New York: W.W. Norton.

Friedman, M., & Marsella, A. (1996). Posttraumatic stress disorder: An overview of the concept. In A. Marsella, M. Friedman, E. Gerrity, & R. Scurfield (Eds.), Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research and clinical applications. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Gelinas, D. (1995). Dissociative identity disorders and the trauma paradigm. In L. Cohen, J. Berzoff, & M. Elin (Eds.), Dissociative identity disorder (pp. 175-222). Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Gibson, E. (1999). The impact of political violence: Adaptation and identity development in Bosnian adolescent refugees. Unpublished Masters thesis submitted to Smith College School of Social Work.

Gil, E. (1992). Outgrowing the pain together: A book for spouses and partners of adults abused as children. New York: Bantam.

Grier, W., & Cobbs, P. (1968). Black rage. New York: Basic Books.

Herman, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery. New York: Basic Books.

Kaufman, J., & Zigler, E. (1987). Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57 (2), 186-192.

Kersky, S., & Miller, D. (1996). Lesbian couples and childhood trauma: Guidelines for therapists. In J. Laird & R. Green (Eds.), Lesbians and gays in couples and families. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Krystal, J., Kosten, T., Southwick, S., Mason, J., Perry, B., & Giller, E. (1996). Neurobiological aspects of PTSD: Review of clinical and preclinical studies. In A. Marsella, M. Friedman, E. Gerrity, & R. Scurfield (Eds.), Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research and clinical applications. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Kudler, H., Blank, A., & Krupnick, J. (2000). Psychodynamic therapy. In E. Foa, T. Keane, & M. Friedman (Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD (pp. 176-198). New York: Guilford Press.

Manson, S. (1997). Cross-cultural and multiethnic assessment of trauma. In J. Wilson & T. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 239-266). New York: Guilford Press.

Marsella, A., Friedman, M., Gerrity, E., & Scurfield, R. (1996). Ethnocultural aspects of posttraumatic stress disorder: Issues, research, and clinical applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

McCloskey, L., & Walker, M. (2000). Posttraumatic stress in children exposed to family violence and single-event trauma. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 108-115.

Miller, D. (1994). Women who hurt themselves: A book about hope and understanding. New York: Basic Books.

Mock, M. (1998). Clinical reflections on refugee families. In M. McGoldrick (Ed.), Re-visioning family therapy: Race, culture and gender in clinical practice (pp. 347-359). New York: Guilford Press.

O’Connell, M., & Higgins, G. (1994). Resilient adults. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers.

Ogden, T. (1991). Projective identification and psychotherapeutic technique. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson.

Pearlman, L., & Saakvitne, K. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. New York: W.W. Norton.

Pinderhughes, E. (1998). Black genealogy revisited: Re-storying an African-American family. In M. McGoldrik (Ed.), Re-visioning family therapy: Race, culture and gender in clinical practice (pp. 179-199). New York: Guilford Press.

Pouissant, A., & Alexander, A. (2000). Laying my burden down: Unraveling suicide and the mental health issues among African-Americans. Boston: Beacon Press.

Rutter, M. (1993). Resilience: Some conceptual considerations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14, 626-631.

Scharff, D., & Scharff, J. (1987). Object relations couple therapy. New York: Jason Aronson.

Schore, A. (2001) The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 201-269.

Sedlak, A., & Broadhurst, D. (1996). Executive summary of the third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Printing Office.

Shapiro, J., & Applegate, J. (2000). Cognitive neuroscience, neurobiology and affect regulation: Implications for clinical social work. Clinical Social Work Journal 28(1), 9-21.

Sheinberg, M., & Frankael, P. (2001). The relational trauma of incest: A family based approach to treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Terr, L. (1999). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. In M. Horowitz (Ed.), Essential papers on posttraumatic stress disorder (pp. 61-81). New York: New York University Press.

Trepper, T., & Barrett, M. (1989). Systemic treatment of incest: A therapeutic handbook. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

van der Kolk, B. (1996). The body keeps score: Approaches to psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. In B. van der Kolk, A. McFarlane, & L. Weisaeth (Eds.), Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society. New York: Guilford Press.

Walker, L. (1979). The battered woman. New York: Harper & Row.

White M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W.W. Norton.

Zur, J. (1996 Winter). From PTSD to voices in context: From an “experience-far” to an “experience near” understanding of responses to war and atrocity across cultures. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 42, 305-317.

Kathryn Basham is Associate Professor, Smith College School for Social Work, Lilly Hall, Northampton, MA 01063, USA (E-mail: [email protected]).

Presented at the 3rd International Conference in Health and Mental Health, Tampere, Finland, July 1-5, 2001.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Transforming the Legacies of Childhood Trauma in Couple and Family Therapy.” Basham, Kathryn. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 3/4, 2004, pp. 263-285; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 263-285. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].