The Long-Term Psychosocial Effects of Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment on Children and Their Families

SUMMARY. Using both qualitative and quantitative methods, a study of 77 families was undertaken to examine the long-term psychosocial effects of cancer on children and their families. This paper focuses specifically on the findings in relation to the parents’ subgroup of the overall study. Key findings were that the majority of parents and their children readjust to ordinary family life following completion of treatment. Gender differences in parents’ coping mechanisms emerged. The period immediately following the cessation of treatment can create feelings of isolation and vulnerability, and many parents have ongoing worries about their child’s continued well-being. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Parents, children, cancer, survival, siblings, family, effects

INTRODUCTION

The study discussed in this article was concerned with the long-term psychosocial effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment on children and on their families. With over two-thirds of children who develop cancer now achieving disease free survival, the emphasis is shifting from preoccupation with treatment and palliative care to survival and coping with the aftermath of the disease and its treatment. The focus of the study was the psychosocial effects of the disease and its treatment on the children, on other family members, and on the family as a whole. Impetus for the study came from the social workers in oncology based in one of the major children’s hospitals in the Dublin area who approached the Department of Social Policy and Social Work in University College Dublin, Ireland, to set up a research project. Hence, a research plan was jointly designed to answer the questions raised by practice and, in turn, to inform future practice.

In itself, survival following diagnosis and treatment of cancer for children or adults does not ensure quality of life. Along with increased survival rates, therefore, has been “growing concern about the biological and psychological late effects of childhood cancer and its treatment” (Friedman and Mulhern, 1991). Cincotta (1993) describes a child’s cancer as being a family disease since it affects everyone within the family system. Indeed, the child’s adaptation to illness is inevitably complicated by the coping responses of the adults and children who are part of the child’s world. Ultimately, then, the challenge of caring for children with cancer extends beyond those children in active treatment and must take account of all the psychosocial aftermath for parents and children.

This finding echoes a study of twenty-one adolescent survivors by Schroff-Pendley et al. (1997) indicating that children diagnosed during middle childhood or adolescence are more at risk of psychological difficulties than those diagnosed in their infancy. Roberts et al. (1998:16) argue that adolescent cancer patients are “uniquely challenged by cancer treatments as they must confront their own mortality and worry about their health while their peers are typically ignoring or denying these realities.”

The importance of the family in the coping process of childhood survivors of cancer cannot be underestimated. A study by Kupst et al. (1995) found that the most significant predictor of the child’scoping and adjustment was the coping ability of its mother. Knowledge about the father’s role in coping is less documented on account of their lower participation rates in studies relative to mothers (Janus & Goldberg, 1997). Pelcovitz et al. (1996) suggest that the tendency of fathers to use avoidance as a coping strategy to deal with chronic illness in their child may put them at significant risk of developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Findings by Dalquist et al. (1996) indicate that fathers tend to rely on their spouses as their sole means of support, whereas mothers have broader social support networks to turn to when their child develops a serious illness. This concurs with findings in an earlier study by Leventhal-Belfer et al. (1993) that mothers often share such concerns more with friends than with their spouses while fathers did the opposite. Dalquist et al. (1996) suggest that psychosocial interventions focusing only on the mother can run the risk of ignoring the psychological impact of illness on the father. In addition, his potential contribution as a source of support and affirmation for his partner may be lost which can be an important contributor in parental adjustment during a child’s illness. Elliott Brown and Barbarin (1996), in their study of gender differences in parental coping with childhood cancer, suggest that fathers may need ‘permission’ to articulate their emotional responses to their child’s illness. At the same time, social workers need to take account of the importance for fathers of having a sense of control in such a situation of intense stress.

Cincotta (1993) viewed cessation of treatment as a time of transition. Hence, the time when treatment ends may rekindle feelings that have been suppressed since the time of initial diagnosis and bring with it fears about the possibility that the cancer could reoccur. Findings by Van Dongen-Meldman et al. (1995) support the significance of this stage for parents. Their study indicated the presence of late psychosocial effects on parents after treatment ends. On the basis of their results, Van Dongen-Meldman et al. (1995) recommended routine psychosocial follow-up consultations for parents in medical follow-up programmes. Mothers, in particular, may find the post treatment phase particularly stressful. A study by Leventhal-Belfer et al. (1993) found that mothers exhibit a much stronger desire to maintain contact with the health care professionals after their child’s treatment is completed than do fathers. The researchers suggest that this is as a result of mothers more usually acting as intermediaries between health care professionals and the family throughout the period of the child’s diagnosis and treatment.

Heffernan and Zanelli (1997) highlight the tendency to limit research on coping strategies to parents (particularly the mother) and the child with cancer while all but ignoring the siblings in the family. It is only recently, they point out, that research has begun to incorporate siblings in studies of children who survive cancer. Their study found siblings as experiencing major stressors where cancer occurs, resulting in feelings of anger, guilt, fear, anxiety, embarrassment, and frustration. This supports an earlier view put forward by Rollins (1990) who referred to siblings as “the forgotten ones.” Cincotta (1993) suggests that siblings may be at greater risk of psychosocial difficulties than their ill brothers or sisters, a view supported by other studies such as Adams and Deveau (1998), Martinson et al. (1990), Eiser and Havermans (1992), and Chesler (1992).

Hamama et al.’s recent study (2000) indicates that siblings who are young at the time of diagnosis and treatment may be at greater risk of ongoing stress than older children. The latter, they suggest, may have the relative advantage of being able to understand better what is happening during the illness and have more developed emotional and social skills as well as peer support to help them cope. A study by Shields et al. (1995) of family needs when a child has cancer indicates that parents are likely to need assistance in helping them to discuss the situation with other children in the family.

A life once challenged by a potentially fatal illness may never be quite the same again for the individual concerned and, particularly in the case of a child, for other family members and for the family as a whole. Childhood cancer is indeed a family disease that has far reaching psychosocial consequences for all family members. As more children survive it becomes all the more important to understand the psychosocial effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Initially, research tended to focus on the children themselves and their mothers, the latter tending to be the ‘significant other’ in the treatment process. Increasingly, attention is being directed at siblings of the child with cancer and on the roles and responses of fathers. However, the latter is still poorly represented in studies of parents in this context. Even less is known about the role of extended family members in helping parents and children cope with the experience of cancer and its aftermath.

RESEARCH DESIGN

In Ireland, figures from the National Cancer Registry show an average of 130 cancer cases per annum for children less than fifteen years of age. This shows the small population to be researched. Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children in Dublin, Ireland, is a national centre for paediatric oncology. It provides inpatient and outpatient treatment for children throughout the twenty-six counties of the Republic of Ireland. Using a stratified random sampling technique, a nation wide sample of 100 families was selected from a total population of 249 children from the medical records in the paediatric oncology unit in Our Lady’s Hospital. The sample was stratified on the basis of geographical location and to ensure that children with different types of cancer were represented. All children with cancer are treated in the public hospital system that is free, as are the drugs and clinic visits required. The sample selected had the following three criteria: they were children who had survived cancer, they had attended the Oncology Unit since 1992, and they were at least two years post treatment. A letter from the paediatric consultants introducing the research was sent out to each family. This was followed up by a phone call from the researcher to establish whether or not the family was willing to participate and, if they were, to arrange date, time, and venue for the interviews. Home interviews were the preferred option for over 95% of the research sample. Out of the sample of 100, a total of 77 families took part in the research. Of the remaining 23 families, 19 were not contactable, being away at the time of the study or having moved with no forwarding address, and four families refused to participate. The ages of the children ranged from 3 years to 21 years at the time of the study (mean age 12 years). The children’s parents, their siblings living at home, and extended family members (grandparents, aunts/uncles) who had close ongoing contact with the family during the illness were invited to participate in the research.

The methodology included both qualitative and quantitative elements. The quantitative research instruments were chosen to incorporate a broad spectrum of data on the psychosocial effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment on children and their families. The results discussed below focus on the parents’ subgroup with particular emphasis on their experiences, ways of coping and views about the effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment on themselves and their children.

The study used a range of standardised tests with the children who had cancer, the parents’ assessment of their children, and the parents’ own coping strategies. The COPE (Carver et al., 1989) and General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, 1981) was used for the parents in order to identify their coping strategies and their self-perceived health status. For the parents’ assessment of the children, the Social Skills Questionnaire-Elementary and Second Level (Gresham & Elliott, 1990) was utilised. The tests selected for the children were: Culture Free Self Esteem Inventory (Battle, 1982); Children’s Loneliness Questionnaire (Asher, 1985) for the younger children, and the Offer Self Image Questionnaire Revised (Offer, 1992) for the adolescents.

As well as standardised measures, in-depth interviews were carried out with the research participants. Interviews took place in the family home or in an alternative setting such as the hospital, depending on what suited the family. Fathers and mothers were invited to participate in the interviews as well as completing the standardised instruments outlined above. The children and their siblings who had sufficient language skills also participated in the in-depth interviews. For younger children and their siblings, simple drawings of hospital scenes were used to stimulate discussion. In addition, the children and their siblings were asked what would be their three wishes. The purpose of this was to gain some measure of the immediacy of health in relation to other aspects of their lives at the time of the study.

RESULTS

Altogether, a total of 74 mothers and 46 fathers took part in the research as well as 38 siblings and 13 other relatives. Forty-two of the children who survived cancer were interviewed. Thirty-one percent of families lived in the greater Dublin area reflecting the population distribution whereby almost one-third of the total population reside in the area. The remainder resided throughout the rest of the country. Only a very small proportion (3%) of the children were only children; the majority (80%) had 1-3 siblings, while 17% had 4 or more siblings. As paediatric oncology is provided only through the public health sector, all socio-economic groups were represented in the sample. The breakdown for this was as follows: 4% professional workers; 12% managerial and technical; 19% clerical; 23% skilled manual; 14% semi-skilled; 5% unskilled; 9% farmers, 9% unemployed; 2% pensioners, 2% students, and 1% attending a training scheme. Over 90% of the parents were married and both were the child’s natural parent. Ireland has until very recently been a mono-cultural society. This was reflected in the survey population whereby all of the sample were Irish born and of Irish descent. It is likely that if such a study were to be repeated a decade on, the changes in emigration with increasing numbers of refugees/asylum seekers would be apparent. In relation to diagnosis, a wide spectrum of cancers was represented with a total of 18 different diagnostic categories. The most prevalent cancers were Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (19%), followed by Hodgkins Disease (9%), Wilms Tumour and Neuroblastoma (8% each), and Rhabdomyosarcoma (6%).

QUANTITIVE FINDINGS–PARENTS

COPE Scale

COPE is a measure used to assess both levels of coping and methods of coping of adults. In this study the COPE Scale was used to assess how well the parents coped in relation to the population in general. The Scale, which is self-administered, addresses both the thought process and the actions in relation to coping. Parents were asked to relate each item to their own experiences and score each on a level of 1-4 with each score having a related value from 1 ‘I usually don’t do this at all’ to 4 ‘I usually do this a lot.’ Scores were divided into 15 component scales and then compared with norm mean scores from the COPE manual.

As can be seen in Table 1, overall, the results showed that parents in the study have average levels of coping in relation to the norm levels. A clear exception was the positive relationship between having a child with cancer and seeking comfort through increased involvement in religious activities, the norm for this item being 8.82 with 11.55 the score for the parental sample. The sub-sample of mothers with a mean of 12.58 had highly significant results in this respect.

More detailed examination of the sub-scales identified some interesting findings, particularly in relation to gender differences. While the parents overall sought external support less than the norm, mothers in the study made greater use of many coping strategies, internal and external, than did fathers. In relation to seeking instrumental social support, the parents as a whole scored .77 below the norm of 11.5 while fathers in the sample were 1.7 below it. As regards seeking emotional social support, there were even greater differences (with the norm of 11.01, parents as a whole scored 1.6 below the norm with the sub-sample of fathers scoring 3.23 below it). Indeed, the most striking differences was the mothers’ higher use of many coping strategies both internal and external and the fathers’ tendency to rely on mental disengagement (norm 9.66, sample as a whole 7.97, sub-set of fathers 7.49), denial (norm 6.07, sample as a whole 6.74, sub-sample of fathers 6.86), and the use of alcohol/drugs as coping mechanisms (norm 1.38, sample as a whole 2.68, sub-sample of fathers 2.91). On the other hand, mothers had higher levels of suppression of competing activities than did fathers (norm of 9.92, sample as a whole 10.72, sub-sample of mothers scoring 11.06 in comparison to the fathers’ score of 10.29). A likely explanation for this is that the mother’s focus has continued to be on the child’s ongoing emotional and physical needs. Comparison of the data in relation to socio-economic status and marital status of the participants did not yield any statistically significant differences. Overall, the results indicated that mothers have an increased tendency to cope better and more effectively than fathers in circumstances of their child developing and surviving cancer.

TABLE 1. Mean Scores for COPE by Gender of Sample

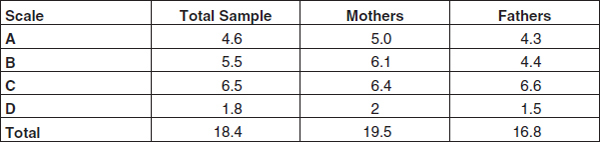

The General Health Questionnaire is a 28 item self-administered questionnaire divided into four scales that assess four different elements of general health: (A) general level of health, (B) sleep problems, (C) sense of control, and (D) feelings of self worth. It measures respondents’ perceptions of their current physical, mental, and emotional well-being, through the use of negative and positive questions which are scored on a Likert score scale from 0 to 3 for four possible response items.

As can be seen from Table 2, the total sample scored a mean of 18.4 with an individual item mean of 0.66. Hence, the mean Likert score per item for this population was 1 that denotes the ‘same as usual’ health levels or ‘no more than usual’ negative health levels. Within this total, fathers scored a total mean of 16.8 while mothers scored 19.5. This difference of 2.7 in the total mean between them indicates a significant relationship between gender and health perceptions in the study population. Comparison of the respondents in relation to socio-economic status and marital status found no significant differences within the study population.

The results showed the parents did not regard their current state of health as any different than it had been in the past. It should be noted that the questionnaire relates only to current perceptions of health levels and is neither retrospective nor prospective. The parents’ perceptions of their own health status at the time of the child’s illness is, therefore, unknown. However, the results indicate that the health levels of the parents of a child with cancer undergoes no lasting change and that health status returns to the normal for most parents. When gender differences were taken into account, it was found that mothers reported sleep difficulties more frequently than did fathers. In addition, the fathers were more likely to consider their general health as normal in comparison to the mothers who perceived themselves as having relatively more negative health status. An examination of those who scored badly on both the COPE and the GHQ (i.e., poor health and poor coping) showed no consistent minority group emerging other than the fact that all were female.

QUALITATIVE RESULTS–PARENTS

A total of seventy-four mothers and forty-six fathers took part in the qualitative interviews. The participation rate for fathers was a particularly positive feature of the research overall as studies of parents tend to either not include fathers or report a very low participation rate for fathers. Although some parents did find it upsetting to talk about their child’s illness, particularly the diagnosis and critical stages in the illness trajectory, all wished to continue with the interview. In fact, many families openly welcomed the opportunity to sit down as a family and speak openly about their experiences. An Interview Guide was developed based on the literature review and discussions with professional staff and a small group of parents who were not selected for the research sample. The guide was divided into the following themes: experiences of diagnosis and treatment including information and support available to the family; perceived changes in the child as a result of cancer treatment; effects on the family as a whole, on the marital relationship, on the child and on their siblings where relevant; current perceptions about the ongoing effects on the child, and anticipations for their future.

TABLE 2. Mean Likert Scores for GHQ Scales A-D by Gender

Memories of Diagnosis

All parents had vivid memories of the time of diagnosis. Over three-fifths commented specifically on their immediate reactions. Feelings of shock, despair and fear predominated: ‘I suppose my initial reaction was shock, disbelief and after that it turned to a certain amount of anger as well.’ A common experience was feeling ‘blank’ and difficulty remembering exactly what was said or what they had been told when their child was first diagnosed. ‘I think we heard the word cancer and we could hear nothing else.’ Parents equated the experience with a nightmare and fear of the unknown. A small number of parents reported that they had wanted to be left alone and not to have to talk to anyone on hearing the news because they felt physically and mentally unable to communicate. Medical jargon had to be deciphered also: ‘I got on the phone (to my husband) and told him to come quickly. I said I’m in an oncology unit and I haven’t a clue what that means at this moment but I think it’s something bad.’

While negative emotions not surprisingly predominated, just under a quarter of parents reported feeling very upset but, at the same time, not surprised or even somewhat relieved on hearing the diagnosis. ‘Something kept telling me that something bad was wrong with him. I wasn’t one bit shocked.’ ‘Shocked but relieved as well because I knew that whatever they could do they were going to do.’ Almost all had considered the possibility that their child might die, the word ‘cancer’ being equated to a death sentence for many of the parents. ‘I thought she was dying, no I thought she was dead actually … Once she (the doctor) said ‘cancer’ that was it. As far as I was concerned she was finished, gone.’

Adequacy of Information Received

Just under one-half of the parents felt they had been given adequate information during their child’s illness. ‘He (the doctor) was open and honest with me. He gave me all the information I needed. He held nothing back and I think that is what gave me the strength to cope.’ The rest of the parents, who were in the majority, were dissatisfied in this respect, largely in relation to the quantity of information received as well as the lack of opportunity to ask questions and get answers that were intelligible to them. ‘I think they should have been able to tell us better or in a different kind of way. Maybe gear it up better for us. It was very blunt and short.’ A small minority of parents considered that they had been given more information than they would have wished to receive. ‘I wouldn’t want to know all these details … I remember they gave me booklets to read and I remember opening them and it was horrendous.’

Experiences of Treatment

Not surprisingly, all of the parents had graphic memories of the treatment phase and its effects on the child. Seeing their child experiencing the physical effects of treatment such as weight and hair loss, the emotional effects of paranoia, aversion to medication, depression and unease as well as watching them endure treatments that were painful and distressing was very traumatic for parents. They also recalled their own feelings of worry, depression and a sense of being in a constant state of disarray. ‘You felt it, you slept it, you’d eat it.’ Seeing other children on the ward who were very ill added to the overall state of distress ‘You’d get attached to some of the little kids and they pass away and you feel lousy that they’re gone.’ For parents living a distance from the hospital, travelling added further to stresses ‘It’s a long journey and with a sick child, it’s longer again.’

Two-thirds of parents had more positive than negative views about hospital personnel during the treatment process. What they valued most was being included in the process, encouraged to ask questions, and having their opinion valued and the caring approach of staff. ‘They were always ready to talk to you which meant an awful lot. There was always somebody’s shoulder there for you and it didn’t matter whether it was during the day or three o’clock in the morning, which was great.’ One-third of parents had more negative views, the most common complaint related to the staff being too busy to talk to them. Another common grievance was the quality of the facilities in terms of environment, accommodation and food.

Looking back at the treatment stage, several parents remarked on how quickly the time had gone by: ‘They were the quickest six months I’ve ever known but each day was the longest day of my life.’ The love-hate relationship felt by the majority of parents about the oncology unit was encapsulated by one parent’s comment that ‘we love the place but we never want to see it again.’

Sources of Support

In terms of support to help them get through the time of diagnosis and treatment, members of the extended family were seen as the major source of support. ‘I would never forget my family. I couldn’t have got through it without them.’ Another parent commented ‘I have one sister … she was great. She took the kids and everything and gave us a break.’ Next in ranking order came other parents who were also going through the experience of their child being treated for cancer. The sense of bonding and the sharing of knowledge were key elements in this. ‘You were in the same situation and they (other parents) were the only ones who understood.’ Neighbours and friends came next, followed by professional staff within and outside the hospital context including such diverse personnel as the family dentist, pharmacist, lab technicians as well as doctors, nurses, and social workers. Specific reference was made to the key role that religious beliefs played for over one-half of the parents, particularly mothers, which is consistent with the results of COPE described above.

Support of professional staff was something that was greatly missed when the child was discharged from treatment. In fact, once the euphoria of discharge had passed, parents found the sense of isolation and aloneness post treatment to be very difficult. ‘You come home on cloud nine but just after finishing chemo(therapy) is the worst part–for the parents anyway.’ ‘When you bring your child home, that’s when you’re totally alone.’ It was strongly felt that a support service would have been of enormous help at this crucial time. ‘I had all this information in my head. It would have been nice if there was someone there that would be able to talk to me in that language.’ What, to outsiders, was regarded as a success story was not necessarily so from the parent’s viewpoint, and this could increase their sense of isolation and need: ‘It’s harder for the one (parent of a child) that lives. It’s like a life sentence. I think they need help as much as if a child dies.’ It is of particular note that the negative psychological effects of the experience on the parents themselves were seen to emerge most often when treatment was completed.

Impact on Family Relationships

In hindsight, one-third of the parents regarded the experience as having had an overall positive effect on family relationships in the sense of becoming closer, living in the present, and being less preoccupied with material things. ‘We go out and about and do things, not put them off.’ On the other hand, just over one-quarter saw the experience as having had an overall negative effect. The parents had focused on the sick child to the detriment of their other children, and there remained a general feeling of insecurity, worry, and fear. ‘I don’t know if we will ever be the same again.’ ‘You’re not as secure in your life. You realise that things can go very wrong.’ The remainder considered that the illness, while very traumatic at the time, had had no long-term effects on the family. ‘Our everyday life is the same as any other normal family–if there is a normal family, if there is such a thing.’

Impact on the Parents and the Marital Relationship

The majority of parents interviewed (almost three-quarters) saw their own relationship as having strengthened as a result of their child’s illness. As one parent described it, ‘I’d say it definitely grew us closer in our marriage. We just realised that we needed each other to get through it.’ Less than one-quarter of the parents considered that the experience of having a child with cancer had had some negative impact on their couple relationship, while a small minority found the strain on their marriage as intense, leading to breakdown and near breakdown in a few instances ‘… (my husband) … was an alcoholic from the time we got married and we always had problems and I think (child’s) illness blew it all up. That was the end of it, I had enough.’ Only a very small proportion regarded it as having neither positive nor negative effects.

The fathers interviewed had less to say than did the mothers about how the child’s illness had affected them individually and as a couple. Just over one-fifth of fathers reported it had had no effects; the remainder considered the experience had affected them in a number of ways. The most common reaction was a change of perspective and priorities: ‘It would teach you a lesson and give you a different outlook on life. You soon learn, I don’t worry about work any more.’ The experience had, they thought, made them more patient, more over-protective of their children and more attentive towards them: ‘It makes you softer.’ Aminority considered that it had affected them in a negative way only, leaving them with feelings of anger, bitterness, depression, short-temper and fear of the future.

Only a tiny minority of mothers felt that they were personally unaffected in the long term. While mothers had more to say than fathers about the effect of the child’s illness on themselves, the responses of both were similar in many respects. The most common effect was a change in life-perspective: ‘It changed my whole attitude to life, to be honest. You realise how precious life is.’ Being over-protective of the child and more likely to ‘spoil’ them was another shared reaction. Some differences between fathers and mothers were that the latter specifically mentioned both the positives of becoming more self-confident, independent, and self-motivated and its negative effects on their physical and mental health. Negative physical effects identified by mothers were weight loss, sleeplessness, nausea, and premature ageing.

Perceived Changes in the Child

Virtually without exception, the parents believed that their child had changed in some way as a result of the illness. The perceived changes varied widely and ranged fairly evenly from very positive to very negative. ‘Withdrawn,’ ‘introverted,’ ‘difficult,’ ‘disinterested’ were some of the terms used to describe the negative effects while others were viewed as having become more ‘outgoing,’ ‘caring,’ ‘mature,’ and ‘confident.’ The experience of illness had left its effects in terms of aversion to medication of any sort, fear of becoming ill again, fear of medical personnel and medical environments, and generalised anxiety ‘She’s a terrible worrier, she’s afraid something might happen to her and we won’t be there to mind her.’ The very few parents who saw no changes attributed this to the very young age at which the child’s cancer was diagnosed and treated. ‘He had one of the best defences of the lot, lack of knowing.’

Regarding the children’s current health status, three-quarters reported their child as having physically recovered fully from the cancer and its treatment. ‘I look on her now as being cured and safe because she’s growing and all the normal things seem to have happened.’ The remainder cited ongoing physical effects such as low energy levels, eyesight or hearing problems, bowel problems, and the issue of future sterility. ‘When he grows up and realises he’s sterile and he might never have a sex life … we’ll have to deal with it in the future.’

Effects of the Illness on Siblings

All of the parents were conscious of the effects of the illness on their other children. Again, there was a mixed response in terms of positive and negative effects although, in this respect, the negatives outweighed the positives. Indeed many of the parental responses were permeated with a sense of guilt about the other children in the family. Parents spoke about being focused on the child with cancer at a cost (to their other children) of time spent with them and attention paid to their needs. ‘She really lost two years with us … She really lost out on a lot.’ Changes reported in siblings included fear, resentment, attention-seeking, guilt, worry, independence, and ongoing protectiveness in relation to the ill sibling. Problems at school, bed-wetting, and increased physical ailments were reported also.

In some respects, the parents felt that the siblings had suffered more than had the child with cancer. ‘She (sister) was actually worse and I think she suffered worse. She’s more insecure … probably she had to learn a hard lesson.’ This quote reflected the fact that the impact of the experience was often seen as ongoing. For example, another parent found herself shocked by a question posed by the brother of the child who had cancer years previously. ‘It was only last year that he said he was worrying and asked ‘Was it me that caused the cancer?’ I knocked him.’ Relationship issues were linked to the siblings’ experiences during the illness. One parent commented ‘She kind of got very independent and even to this day, she sort of doesn’t need anybody. She’s very hard, actually. She doesn’t like cuddles …’ In another family, the sibling was seen to take on ‘a very responsible role. She maybe hid a lot of what she was feeling from us.’ In the parents’ view, siblings coped best if they got as much attention as possible, were kept informed and involved in the illness process, and had other family members to give them the extra attention needed at the time ‘She got so much attention, she coped very well. She had her Granny.’

Parents were very aware of whether or not they treated the child with cancer differently from their other children. There was an equal division between those parents who had made a conscious effort not to give any sort of preferential treatment and those who felt that a child who had had cancer needed extra attention and care. Having a very ill child was seen to strengthen the parent-child bond, increase awareness of the uniqueness of the child within the family, and making the parent more ‘tuned in’ to the child’s needs: ‘It couldn’t be just a normal relationship. We spent an awful lot of time together.’

Anticipations for the Future

In relation to their own feelings about the child’s future health, over two-thirds of the parents felt positive while the remainder expressed worries about some or all aspects of their child’s health. Concern for the child’s future focused on fears about survival as well as on the development of personal relationships, education, and employment. ‘You see–it’s over but it’s not over. That’s the worst of it now. I think that’s the hardest. I know cancer can reoccur.’ In this context, searching for a cause, self-blame, anger, and guilt were ongoing preoccupations for this group of parents for whom the experience was still a dominant factor in their lives. ‘You often say to yourself ‘Why did it happen?’ ‘What did I do?’ You’d be blaming a lot of things for it.’

Interestingly, half of the parents stated that the child’s illness and treatment was never discussed within the family. Most of these ascribed this to the children themselves not wanting to talk about it ‘… he never mentions it. He seems to have put it completely to the back of his head, he doesn’t want to know about it.’ Another commented ‘…she doesn’t want any of her friends to know that she was sick.’ In some cases, the parents stated that they avoided mention of the illness on account of feelings of guilt and/or denial.

Three Wishes

In the interviews with the children with cancer and with their siblings, they were asked if they could have a magical three wishes, for what would they wish. The purpose of this was to find out the extent to which illness was reflected in their wish list. This question produced interesting results. While a wide range of wishes were expressed by the children with cancer, they could be broken down into categories relating to: material changes (‘be rich,’ ‘live in a mansion’); having new things (‘a TV in my room,’ ‘a computer game,’ ‘a horse’); meeting famous people (‘Michael Schumacher,’ ‘Boyzone’); going on special holidays (‘go to Eurodisney,’ ‘visit cousins in Canada’); ambitions (‘be a singer,’ ‘play for Manchester United’); changes in the self (‘be thinner,’ ‘have longer hair’); and those specifically relating to illness (‘that never got a tumour,’ ‘get better,’ ‘illness never to happen again’).

The wish list of siblings was equally wide ranging and reflected the same broad areas. The siblings’ wishes in relation to illness reflected their experience of illness within the family (‘that he was never sick,’ ‘for it (cancer) never to happen to kids,’ ‘to have nobody sick,’ ‘that she gets well properly, no hospital, no moods’). Table 3 shows the percentage of wishes relating to illness for the children with cancer and their siblings. Given the context in which the wish question was asked, it could be expected that wishes in relation to illness would be expressed. It is interesting to note the overall percentage of children who expressed wishes relating to illness and that it was the siblings, rather than the children with cancer, who expressed such wishes more often.

DISCUSSION

The realisation that your child has cancer is likely to be one of the most stressful life events a parent will experience. An overwhelming sense of despair can disrupt the lives of each member of a family at an emotional, physical, and practical level. Professionals in the field of paediatric oncology are witness to such effects on families. Social workers, in particular, on account of their family oriented involvement, are aware of the degree of upset and disruption a diagnosis of cancer can have on the family unit. Fortunately, the success rate in treating children with cancer is improving. More will now survive the disease than will die. Of increasing concern, therefore, is whether or not diagnosis and treatment of cancer will have long-term psychosocial effects on the child, the parents, siblings, and on the family as a whole. One means of assessing this is through the use of standardised instruments in relation to pertinent areas such as coping and perceived health status. Increasingly, however, the importance of incorporating the respondents’ subjective experiences and views is recognised.

TABLE 3. Percentage of Wishes Relating to Illness for Children with Cancer and Their Siblings

The use of qualitative and quantitative methods in this study provided a rounded picture of the children and their families after a substantial time lapse since completing treatment. The fundamental question was whether the diagnosis and treatment of cancer had had serious long-term effects on the children’s psychosocial development. Overall, a positive picture emerged from this study of the majority of children and families able to move on with their lives in the aftermath of cancer. However, within these very positive findings, there is evidence of a small number of children and their families who have ongoing difficulties. Analysis of the data by diagnostic group, socio-economic circumstances, family composition and gender did not show any significant differences. The only factor in the children’s adjustment seemed to be one of age indicating that those approaching or having reached adolescence may benefit from psychosocial follow-up.

A particular feature of this study was the relatively high participation rate of fathers. Our findings on the coping strategies of mothers and fathers were similar to the studies cited above. The results of the COPE Scale and the qualitative interviews showed that fathers typically used the coping strategies of avoidance and dependence on their spouses as their sole means of emotional support. Knowledge of such differences is important for understanding how each cope with stressful situations and indicates how professionals can use this knowledge to involve both parents meaningfully in the treatment process. It is also noteworthy that the parents in this study identified the period immediately following the cessation of treatment to be particularly stressful.

Only a small number of grandparents took part in the study. Those who did participate saw their role as being supportive to their own child, the parent of the child in treatment. However, the grandparents indicated a very negative view of cancer, regarding it as a death sentence. If they can be helped in their role as providing appropriate emotional and practical support, it would be important that they be provided with up to date information on improved treatment outcomes.

In hindsight, one of the parents’ major concerns was the impact of the illness on the siblings. At the time of diagnosis and treatment, parents were aware of the problems for siblings but were often unable to deal with their needs effectively on account of the physical and emotional demands of having a child with cancer. From the interviews it was evident that feelings of neglect and of being of lesser importance on the part of siblings do not necessarily diminish when the treatment has ended successfully. Such findings indicate the need for them to be included as much as possible at the treatment stage and that parents are helped, in terms of information, support, and practical help, to respond to the needs of siblings in these circumstances. Support services for siblings, both at the time of treatment and subsequently, could offer help to this subset of the family who would seem to be particularly vulnerable.

Carrying out the research in the families’ homes inevitably led to the dangers of distraction and interruption of the research process. However, this was well compensated by the fact that it was carried out in the respondents’ own familiar setting. While the response rate was very high, there was a sizeable percentage of the original sample (19%) that was non-contactable and a further 4% who refused the invitation to participate. The question arises as to whether or not this subset would have been different those who participated in the study. The importance of social support for families where a child is seriously ill is evident in the results. The particular role played by close family members in providing support is clearly important. The grandparents who participated in the study provided interesting insights into their role and perspectives. However, the overall numbers of grandparents who participated was relatively small.

The results of this study overall indicated that most of the children were well adapted and coping effectively with all aspects of their lives. Further, in recollecting the period of diagnosis and treatment, the children’s memories were by no means only negative. Parents for the most part were able to put the experience in the past in spite of some ongoing concerns about future implications for the child of having had cancer. Many of the parents were also able to identify some positive effects on themselves and on their family as a whole in the sense of changing priorities and bringing the family closer together. These findings are most encouraging for children currently undergoing treatment or recently post-treatment.

Adams, D.W. & Deveau, E.J., 1988, Coping with Childhood Cancer: Where Do We Go From Here? Canada: Kinbridge Publications.

Asher, S.R. & Wheeler, V.A., 1985, Children’s Loneliness: A Comparison of Rejected and Neglected Peer Status, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 53, pp. 500-505.

Battle, J., 1992, Culture-Free Self-Esteem Inventories, Austin: Pro-Ed.

Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F. & Weintraub, J.K., 1989, Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically-based Approach, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 267-283.

Chesler, M., 1992, Introduction to Psychological Issues, Cancer Supplement, Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 3245-3268.

Cincotta, N., 1993, Psychosocial Issues in the World of Children with Cancer, Cancer Supplement, Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 3251-3260.

Dalquist, L., Czyzewski, S. & Jones, C., 1996, Parents of Children: A Longitudinal Study of Emotional Distress, Coping Style and Marital Adjustment Two and Twenty Months after Diagnosis, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 541-544.

Eiser, C. & Havermans, T., 1992, Children’s Understanding of Cancer, Psycho-Oncology, Vol. 1, pp. 169-181.

Elliott Brown, K.A. & Barbarin, O.A., 1996, Gender Differences in Parenting a Child with Cancer, Social Work in Health Care, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 53-71.

Friedman, A. & Mulhern, R., 1991, Psychological Adjustment among Children who are Long-term Survivors of Cancer in Johnson, J.A. & Johnson, S.B. (Eds), Advances in Child Health Psychology, University of Florida Press.

Goldberg, D., 1981, General Health Questionnaire, NFER-Nelson.

Gresham, F.M. & Elliott, S.N., 1990, Social Skills Rating System, Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Hamama, R., Ronen, T. & Feigin, R., 2000, Self-Control, Anxiety, and Loneliness in Siblings of Children with Cancer, Social Work in Health Care, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 63-83.

Heffernan, S. & Zanelli, A., 1997, Behavioural Changes Exhibited by Siblings of Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Comparison Between Maternal and Sibling Descriptions, Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, Vol. 14, No. 1., pp. 3-14.

Janus, M. & Goldberg, S., 1997, Factors Influencing Family Participation in a Longitudinal Study: Comparison of Pediatric and Healthy Samples, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 245-262.

Kupst, M., Natta, M., Richardson, C., Schulman, J., Lavigne, J. & Lakshmi, D., 1995, Family Coping with Pediatric Leukaemia: Ten Years After Treatment, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 10, pp. 19-41.

Leventhal-Belfer, L., Bakker, A. & Russo, C., 1993, Parents of Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Descriptive Look at Their Concerns and Needs, Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 14-41.

Martinson, I., Gilliss, C., Colaizzo, D., Freeman, M. & Bossert, E., 1990, Impact of Childhood Cancer on Healthy School-Age Siblings, Cancer Nursing, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 183-190.

Offer, D., Ostrov, E., Howard, K.I. & Dolan, S., 1992, Offer Self-Image Questionnaire Revised, California: Western Psychological Services.

Pelcovitz, D., Goldenberg, B., Kaplan, S., Weinblatt, M., Mandel, F., Meyers, B. & Vinciguerra, V., 1996, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Mothers of Pediatric Cancer Survivors, Psychosomatics, Vol. 37, No. 2., pp. 116-127.

Roberts, C.S., Turney, M.E. & Knowles, A.M., 1998, Psychosocial Issues of Adolescents with Cancer, Social Work in Health Care, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 3-18.

Rollins, J., 1993, Childhood Cancer: Siblings Draw and Tell, Pediatric Nursing, Vol. 16, No.1, pp. 21-27.

Schroff-Pendley, J., Dalquist, L. & Dreyer, Z., 1997, Body Image and Psychosocial Adjustment in Adolescent Cancer Survivors, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 29-43.

Shields, G., Schondel, C., Barnhart, L., Fitzpatrick, V., Sidell, N., Adams, P., Fertig, B., & Gomez, S., 1995, Social Work in Pediatric Oncology: A Family Needs Assessment, Social Work in Health Care, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 39-54.

Van Dongen-Meldman, J., Pruyn, J., DeGroot, A., Koot, M., Hahlen, K. & Verhulst, F. (1995), Late Psychosocial Consequences for Parents of Children Who Survive Cancer, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Vol. 20, No. 5, pp. 567-586.

Suzanne Quin is affiliated with the Department of Social Policy and Social Work, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (E-mail: [email protected]).

This study was a joint research project carried out by the Oncology Unit, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin and the Department of Social Policy and Social Work, University College Dublin. It was funded by the Children’s Research Centre, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin, Ireland.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “The Long-Term Psychosocial Effects of Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment on Children and Their Families.” Quin, Suzanne. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 1/2, 2004, pp. 129-149; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 129-149. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].