CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN INVESTMENT DECISIONS

INTRODUCTION

In the previous chapter we saw how investors price common stock when they are making investment decisions. Here, we consider the connection between share prices and the investment decisions made by managers using net present value (NPV) analysis and the NPV rule.

Actually, the approach we take is to consider each investment project as a stand-alone independent company. In so doing, we conceptualize the company as being the sum of its investment projects—what it does for a living.

THE NPV RULE

Net present value has a precise meaning with respect to the market value of a company. The NPV of an investment project is the instantaneous change in the market value of the company that will occur if managers decide to go ahead with the investment. For example, suppose the NPV of a new product proposal is $500 million. If investors agree with management’s assessment of the project’s benefits, the market value of the company will increase by $500 million as soon as management announces that it will go ahead with the new product.

Technically, NPV is defined as the present value of all expected after-tax incremental cash outflows and inflows associated with the project, discounted at the project’s risk-adjusted required rate of return (which is the same as the project’s opportunity cost of capital). And, what amounts to exactly the same thing, we can also define NPV as the present value of the expected after-tax cash inflows less the present value of the expected after-tax cash outflows, with both cash flow streams discounted at the project’s risk-adjusted required rate of return.

Note the close correspondence between this definition and our definition of stock price, where we said that the stock price was the present value of the cash flows expected by the investor, discounted at the investor’s risk-adjusted required rate of return. In effect, the market value of an entirely equity-financed company (one that has not borrowed any money) that distributes all after-tax cash flows to shareholders as cash dividends is simply the sum of the present values of all its current investments in the products and services that it sells for a living. With some modifications, we can show that this definition of the market value of a company’s common stock also holds for companies that have used debt to finance themselves and those that reinvest some or all of the current year’s after-tax cash flows in new projects.

A Stylized NPV Example

We will use a highly stylized example to demonstrate why managers should use NPV to evaluate investment decisions and how NPV is connected to stock prices. For detailed instructions on how to use NPV and other related techniques for capital budgeting, you should consult a financial management textbook.

The Data

Consider a company called Lamprey Products. Lamprey’s management has identified a new product, called Snail Fish. The following information about Snail Fish has been compiled in order to calculate its NPV:

![]() Snail Fish will have a product life of three years; after three years, no one will want to buy any Snail Fish.

Snail Fish will have a product life of three years; after three years, no one will want to buy any Snail Fish.

![]() Cash sales over the three years are expected to be $600,000 a year.

Cash sales over the three years are expected to be $600,000 a year.

![]() Cash operating expenses are expected to be $360,000 a year.

Cash operating expenses are expected to be $360,000 a year.

![]() Fixed assets costing $300,000 must be bought immediately to produce Snail Fish. The assets will be depreciated over three years at the rate of $100,000 a year for both tax and financial reporting purposes.

Fixed assets costing $300,000 must be bought immediately to produce Snail Fish. The assets will be depreciated over three years at the rate of $100,000 a year for both tax and financial reporting purposes.

![]() The marginal tax rate paid by Lamprey Products is 40 percent.

The marginal tax rate paid by Lamprey Products is 40 percent.

![]() The risk-adjusted required rate of return on Snail Fish is 14 percent.

The risk-adjusted required rate of return on Snail Fish is 14 percent.

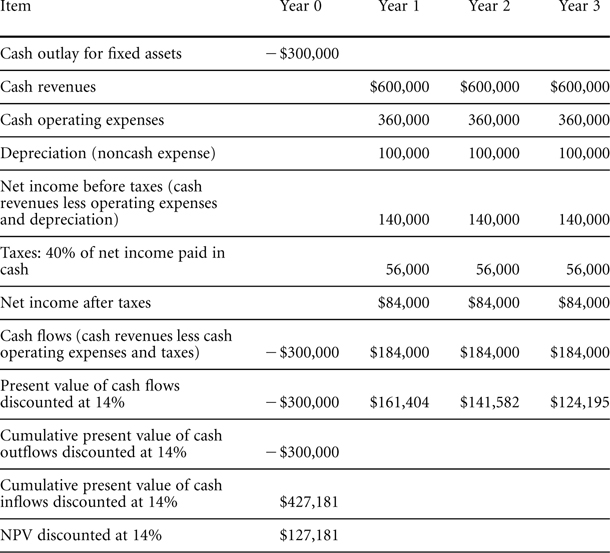

The after-tax cash flows for this project appear in Figure 5-1. The major conceptual point to understand is that the project’s cash flows are not the same as its net income. Observe that for the purpose of calculating net income, the $300,000 cash outlay for equipment is not deducted from revenues in the year it is spent, but instead is spread over the three-year life of the project. This allocation is called depreciation and is a noncash expense. However, depreciation does affect the company’s tax liability, and consequently its cash payments for taxes, because it is considered an expense (a cost) by the Internal Revenue Service. Think of it this way: The $300,000 must be recovered before the project can be said to be profitable—that is, before it generates cash flows in excess of what was spent on the project. The IRS recognizes this and lets you spread this amount over the three-year revenue-generating life of the project.

FIGURE 5-1 NPV CALCULATION FOR SNAIL FISH

So, as shown in Figure 5-1, the after-tax cash flows for the project are –$300,000 at time 0 (today) and $184,000 a year for years 1, 2, and 3. Net income before taxes is $140,000 a year for years 1, 2, and 3, and net income after taxes is $84,000. The difference between net income after taxes and cash flow after taxes is the noncash depreciation charge of $100,000 a year, representing the recovery for tax purposes of the initial $300,000 investment.

The Present Values

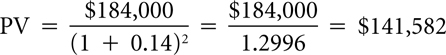

At a 14 percent required rate of return, the present value of the cash outflows is –$300,000, and that of the cash inflows is $427,181. The NPV is $127,181. The formula for calculating the individual-year present values is

where PV = present value

CFt = after-tax cash flow in year t

k = investors’ required rate of return

t = year t

For example, the calculation for year 2 is

Think of the present values this way: At 14 percent compounded annually, you would need to deposit $124,195 today to have $184,000 three years from today. You would need to deposit $141,582 today to have $184,000 two years from today. And you would need to deposit $161,404 today to have $184,000 one year from today. The present value of the cash inflows, then, is the sum of money you would need to deposit today, invested at 14 percent compounded annually, in order to be able to withdraw $184,000 a year for the next three years, or $427,181. But, lucky you! (Or, we should say, lucky Lamprey shareholders.) Lamprey management has found a way for Lamprey shareholders to withdraw $184,000 a year from the bank called Lamprey Products for a deposit today of only $300,000—the cost of buying the equipment to make Snail Fish.

Interpreting NPV

The difference between what Lamprey must invest in this project and what anyone else would have to invest (put in the bank) to get the same cash flows discounted at the project’s required rate of return is called the NPV of the project and is $127,181. We say ‘‘what everyone else would have to invest’’ because the definition of a project’s required rate of return is the rate of return that is normally available to everyone on an investment identical to Snail Fish in terms of risk. So, as soon as Lamprey management announces the Snail Fish project to the public, the total market value of Lamprey’s common stock will increase by $127,181 to ensure that there are no ‘‘money trees’’ in the stock market that will provide investors with returns greater than fair, competitive risk-adjusted returns. In other words, why would anyone put $427,181 in the bank today in order to withdraw $184,000 a year for the next three years when they could buy the rights to an identical cash flow stream from Lamprey Products for only $300,000 (or $350,000 or $400,000)? Because everybody will want to buy Lamprey Products’ stock, the price will rise until it provides the same 14 percent return that you could get everywhere else, which will happen when the total market value of the stock is $427,181.

Now, let’s connect these cash flows and market values to the book value of Lamprey Products. To focus on the critical question of market versus book value, let’s assume that Lamprey Products has total assets of $300,000, all of these assets are cash, and, Lamprey is an all-equity company (meaning that it has used no debt for financing itself) with 10,000 shares of stock outstanding. By accounting definitions, the total book value of the stockholders’ equity is $300,000 and the per share book value is $30. Let’s also have the per share stock price equal the per share book value, $30. At this point, the ratio of the market value of the stock to its book value is 1.0. As soon as Lamprey management announces the Snail Fish project, the total market value of the equity jumps to $427,181 and the per share price to $42.7181. The market-value-to-book-value ratio is now 1.424.

When we explore management compensation schemes in Chapter 8, we describe a system called EVA® that ties managerial pay to the ratio of market value to book value. The greater the ratio of market to book, the higher a manager’s pay. The rationale for this pay scheme is to align the interests of management with those of the shareholders by rewarding managers for making investment decisions with a positive NPV that increase the company’s market-value-to-book-value ratio. The difference between market value and book value is called economic value and is akin to, if not exactly the same as, NPV.

DO INVESTORS BEHAVE AS PREDICTED BY THE NPV RULE?

What evidence is there that investors actually do use cash flows and not net income or short-term earnings per share when they evaluate and price out investment decisions made by management? This question has been examined by many researchers. They have generally found that for companies that announced strategic investment initiatives, the two-day abnormal returns of stock prices increased. Typical findings are that the stock prices of companies that announced major capital expenditures rose by 0.348 percent. For companies that announced new product strategies, the increase was 0.842 percent. For companies that announced substantial increases in research and development expenditures, the increase was 1.195 percent; and for companies that announced joint ventures, it was 0.783 percent.1 Although these percentages appear to be small, consider that a 0.348 percent increase in the market value of the common stock for, say, Heinz is more than $4.75 million. More important, the stock price reactions were positive, not negative as they would be if investors focused on near-term earnings per share and not future cash flows. All these investments had the effect of lowering the current year’s earnings per share relative to what they would otherwise have been, especially the research and development expenditures.

Further evidence supporting the NPV rule as a means for making investment decisions is found in a study by Su Chan, John Kensinger, and John Martin.2 These researchers carefully examined ninety-five research and development expenditure announcements by companies, which they divided into ‘‘high-tech’’ and ‘‘low-tech’’ companies. They found that the average two-day abnormal return was –1.55 percent for low-tech companies and 2.10 percent for high-tech companies, suggesting that investors reward high-tech research but not low-tech research. Perhaps more important for the question of whether investors take a long-term perspective rather than a short-term earnings perspective is their finding about stock price reactions for companies that announce increases in research and development expenditures at the same time that they announce earning declines. The stock price of these companies increased by 1.01 percent even though they reported earnings decreases.

Subsequent studies continue to confirm these results. On average, strategic investments lead to higher stock prices, regardless of whether the investment is classified by accounting rules as a tangible fixed asset or is an intangible asset that is disguised by accountants as an expense.

IMPLICATION OF THE NPV RULE FOR INTERNAL ALLOCATION OF CAPITAL

The NPV rule has very important implications for the internal allocation of capital among the divisions of a company. Think of each division as a separate company or module, with its own risk and return characteristics and its own present value. Add together the values of the modules and you have the market value of the company. In today’s world, where strategists talk about corporate flexibility in terms of putting together or shedding modules, which modules should be kept and which discarded? The answer is: Keep those with positive NPVs and shed those with negative NPVs.

In other words, the NPV rule implies that for allocating capital within the firm (among the modules), investors’ risk-adjusted required rates of return should be used as the cost of capital for evaluating projects, both at the divisional level and within divisions or suborganizational units. Divisions with high risk should have high hurdle or discount rates, and divisions with low risk should have low hurdle rates.

Divisions or modules that fail to achieve the required divisional returns should be shut down, spun off, or sold. An example of how one company approaches this internal capital allocation process, with its implications for divestitures and acquisitions, can be found in Quaker Oats Company’s 1998 annual report.

Quaker has built its operating and financial strategies around creating economic value. The company states that:

When we consistently generate and reinvest cash flows [note, cash flows, not net income] in projects whose returns exceed our cost of capital, we create economic value… . Value is created when we increase the rate of return on existing capital and reduce investments in businesses that fail to produce acceptable returns over time.

Quaker lists as one of its six operating strategies ‘‘improve the productivity of low-return businesses or divest them.’’ It explains this objective by saying:

Our commitment to deliver shareholder returns that exceed our cost of equity challenges us to achieve a consistent return, better than our cost of capital [meaning positive NPVs] in each of our businesses. In 1998, we divested several businesses that did not meet that objective. During the year we sold Ardmore Farms juices, Continental Coffee, Liqui-Dri biscuits and Nile Spice soup cups for $192.7 million. Although those businesses had approximately $275 million in annualized sales, in total, they were negligible contributors to operating income.3

LEGITIMATE AND ILLEGITIMATE CRITICISMS OF THE NPV RULE

Criticisms of the NPV rule and its usefulness for evaluating investment and financing decisions abound. Some are legitimate; others are not. Let’s start with some common wrongheaded criticisms.

One of the most common reasons offered for not using NPV is that the project is mandated by health and safety concerns or government regulations. For example, regulations concerning water or air pollution may require the replacement of old equipment with cleaner new equipment. At first glance, such a project seems to fall outside of a NPV analysis because it generates no cash inflows and looks like a negative-NPV investment. However, if the investment is looked at from a more global perspective, the analysis fits quite well into a NPV framework.

What are the consequences of not complying with the pollution control (or, for that matter, occupational safety) regulations? Among those we can think of are fines, the inability to attract and retain high-quality employees and managers, and severe public relations problems, leading to boycotts and loss of sales and reputation. Properly handled in a NPV analysis, these fines and other ‘‘costs’’ would be translated into negative after-tax cash flows if the company did not undertake the required investments. Therefore, the incremental cash flows from the project are the fines and other losses that the company does not incur as a result of making investments that reduce pollution and improve working conditions.

Another way to think about this problem is to ask whether the owners of the company would be better off if the company were liquidated rather than making the regulatory required investments. Again, the comparison is not to an existing mode of operation that cannot be maintained, but to the future cash flows should the investments not be undertaken.

Another common criticism of the NPV approach is that it doesn’t take qualitative factors such as employee responses to major organizational changes into consideration. We would argue that the problem here is not with the NPV method but with the cash flows used in the calculations. The cash flows have not included the organization costs that the project will impose on the firm.

So, what are some legitimate reasons for not using the NPV rule, or at least not using it in the basic form? Perhaps the best reason for being extremely careful about using the NPV rule when making strategic investment decisions is that these decisions often contain options that will allow the firm to capitalize on future opportunities or to abandon a strategic investment if, with the passage of time and the accumulation of information, it turns out to be not quite what the company expected.

Strategic Options and the NPV Rule

Recall the question we asked in Chapter 3 about whether managers should consider only market (systematic, nondiversifiable) risk or total risk when making investment decisions. There, we said that most of the company’s stakeholders would suffer substantial costs regardless of the reason why the firm failed. Thus, managers would be well advised to consider not only the market risk but also the unique risks of any investment—in other words, the total risk.

For example, the employees of a company have a considerable interest in its success because they would incur substantial adjustment costs were the firm to fail. These costs go beyond the costs of looking elsewhere for employment, especially for highly skilled technical and managerial employees. These individuals typically make major commitments of time and effort to develop company-specific skills and look to the continued growth and success of the company for returns on these investments. These returns are not entirely pecuniary, but also come in the form of promotions, status, and job security. So, firms that can offer their employees and managers security and the prospect of financial success are likely to garner greater employee loyalty and to be able to recruit and retain the ‘‘better’’ workers and managers.

But perhaps there is a more fundamental relationship between the survival of the firm and having employees and other stakeholders make firm-specific investments. We would argue that it is the firm-specific skills amassed by the firm’s employees that make it possible for the firm to earn quasi rents. Expressed in the terminology of financial management, these firm-specific skills enable the firm to find and undertake projects with a positive net present value.

In other words, from a companywide perspective, new strategic positive NPV investments arise out of past strategic investments and what the company already does for a living. For example, had Pfeiffer Vacuum’s previous investments in, say, developing high-technology vacuum equipment for extracting air from potato chip bags not been made, the opportunity for developing the high-technology vacuum processes needed for manufacturing semiconductors would probably not have existed. Therefore, when Pfeiffer Vacuum is considering new strategic investments in vacuum production technology, it needs to consider not only the cash flows from the particular technology or equipment under analysis, but also the value of future options for new products and new markets (say, China or Brazil).

Competitive Analysis Approach

What about the situation facing a division of a company that manufactures products that are also produced by a number of competitors, such as Boeing? Boeing designs, produces, and sells commercial aircraft. Should Boeing continue to do so, and how might Boeing determine whether introducing a wide-bodied aircraft seating 1,000 people is a positive NPV project? An approach frequently found in the management literature is the competitive analysis approach (CAA).

Fundamentally, CAA is a disguised version of the NPV rule that assumes that all competitors are wealth maximizers. We say this because, by definition, a positive NPV project is one whose expected returns are greater than what anyone could earn elsewhere on an equally risky investment. So, for the wide-bodied aircraft to be a positive NPV project for Boeing, Boeing must have some competitive advantage(s) in designing, producing, and selling the aircraft compared to its competitors. If it does not, Boeing is looking at an investment that will leave its stock price, at best, unchanged. So, for Boeing to have a positive NPV on this investment, it must come to the table with a lower cost of capital, better management skills with respect to designing and producing wide-bodied aircraft, and/or other capabilities that its competitors do not possess.

But suppose the governance objective of Boeing’s competitors is not shareholder wealth maximization? Now, even though Boeing knows that it has advantages over its competitors, moving ahead with the project on the basis of CAA could still produce a negative NPV outcome. How? Well, Boeing’s competitors may be subsidized by their governments or may be operating in corporate governance environments that place shareholder concerns below economywide employment and income priorities. In such a case, using CAA to evaluate investment decisions may lead to Boeing’s demise unless it can convince the state of Washington or the federal government to provide similar subsidies.

We used Boeing as an example because its main competitor is Airbus, a consortium of European companies. Historically, some of these companies were at least partially owned by national governments, and Airbus managers were often required to consider the political needs of the consortium members with respect to spreading employment around the various countries when making production decisions.

Another problem with CAA is that it is susceptible to herding decisions. Suppose some new technological means for selling goods and services is created—say e-commerce. This discovery generates a rapid expansion of firms in the e-commerce business. You do a CAA of your proposed e-commerce project and identify a number of competitive advantages for your firm. Does this mean that you have identified a positive NPV project? Not necessarily. Perhaps the industry, as a whole, is really unprofitable. In this case, you may survive longer than others or lose less money, but you haven’t created long-term value for your shareholders.