6. Financial Reporting and Tax Considerations for Mergers and Acquisitions

Market View

In October 2005, Telefonica, a Spanish telecom company, offered to acquire O2, the sixth-largest mobile phone company in Europe, for £18 billion. It was speculated that Deutsche Telekom (DT) and its subsidiary, T-Mobile, which had a known interest in O2, would make a counteroffer, triggering a bidding war between the German and Spanish telecom giants. However, DT announced that it would not bid for O2. Some members of the financial community concluded that DT was probably concerned about getting approval from the Competition Commission, the antitrust regulator in the European Union.

In October 2007, the Financial Times revealed that DT had filed a complaint with the commission, arguing that Telefonica had been able to outbid its German competitor thanks to a Spanish tax rule that gave Spanish companies an unfair advantage compared to their E.U. counterparts.1 This rule, called Article 12.5 of the TRLIS, enabled Spanish companies to offset the goodwill on foreign acquisitions against their domestic tax bill. No such rule existed in other E.U. countries, thus giving Spanish companies the opportunity to outbid their European rivals. DT estimated that the acquisition of O2 had generated €11 billion of goodwill for Telefonica and that the Spanish telecom company would save €4 billion in tax over 20 years—approximately 20 percent of the price it paid for O2. DT argued to the commission that the Spanish government had, de facto, subsidized the acquisition.

The commission launched an investigation to determine whether the tax rule was a state aid in disguise. In December 2009, it concluded that Article 12.5 of the TRLIS was incompatible with the internal market and required Spain to abandon it. Acquisitions prior to December 2007, such as Telefonica’s purchase of O2, were not affected by this decision. However, after this date, Spanish companies were no longer allowed to offset goodwill against their domestic tax bill.

Although mergers and acquisitions (M&As) have historically been a within-country phenomenon, the last two decades witnessed an explosive growth in cross-border M&A activity. For instance, Erel, Liao, and Weisbach (2012) reported that the proportion of cross-border M&As increased from 23 percent of total volume in 1998 to 45 percent in 2007. As companies tried to globalize, they found it less costly and far less difficult to buy access to foreign marketplaces than to try to build that access. With this trend came the need to understand generally accepted M&A accounting and taxation issues on a global basis.

One consequence of a merger or acquisition is usually the requirement of preparing consolidated financial statements—that is, preparing a single set of financial statements reflecting the combined operations of an acquirer and any majority-owned subsidiary companies. The requirement of preparing consolidated financial statements for financial reporting purposes and for tax purposes is rarely the same across countries. Hence, this chapter focuses on understanding how, and when, the financial data from two (or more) companies are aggregated in consolidated financial statements following mergers or acquisitions.

Specifically, this chapter addresses the following key questions:

• Under which circumstances are consolidated financial statements prepared for financial reporting purposes?

• Under which circumstances are consolidated financial statements prepared for income tax purposes?

• What is goodwill, how is it accounted for, and what are its tax implications?

1 Financial Reporting: To Combine or Not to Combine?

In most countries, when one company obtains a majority shareholding in another, the parent company is required under local generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to prepare consolidated financial statements.2 These combined financial statements were originally introduced to avoid the potential problem of information overload that can result if investors receive individual financial statements for a multitude of companies belonging to a conglomerate or holding company. However, combining the operating results of many diverse businesses leads to a different type of analytical problem: It obscures the results of the various combined businesses and precludes investors from determining exactly which businesses are successful and which are not. This disclosure problem is mitigated, to some extent, by the disclosure of sales and income data along key business segment lines (segment reporting). Unfortunately, equity markets still struggle to value diversified companies, as evidenced by the fact that the aggregate market value assigned to a conglomerate is frequently less than the value assigned to the individual business components comprising the conglomerate (in essence, a “conglomerate discount”). Consolidated financial statements almost certainly exacerbate this valuation problem.

In some countries, consolidation of majority-owned subsidiaries is not mandatory; in others, consolidation is required only when a parent company is publicly held.3 When a subsidiary is not consolidated, it is accounted for on the parent’s financial statements using either the cost method or the equity method, with results that are not entirely satisfactory from an analytical perspective.

Under the cost method, an acquired subsidiary is recorded as an asset on the parent company’s balance sheet at the original acquisition price. This amount is maintained until it is judged to be permanently impaired, at which point an asset write-down is taken along with an impairment loss. No attempt is made to reflect the operating results of the acquired subsidiary on the parent’s financial statements. Under the equity method, the cost of an acquired subsidiary is likewise initially recorded on the parent’s balance sheet as an asset. This amount is increased (decreased) by the parent’s ownership interest in the subsidiary’s operating profits (losses) and decreased by the amount of any dividends that the parent paid to the subsidiary.

When the cost method is used to account for a majority-owned subsidiary, both the parent’s income statement and balance sheet are likely to be informationally deficient with respect to the subsidiary’s operations. The equity method fully recognizes the operating results of the subsidiary in the parent’s income statement, but the parent’s balance sheet is likely to be informationally incomplete. For instance, neither the cost method nor the equity method adequately portrays a majority-owned subsidiary’s debt position on the parent’s balance sheet. As discussed in the previous chapter, “Accounting Dilemmas in Valuation Analysis,” the parent may as a result appear less leveraged than it actually is.

In short, despite the concern that consolidated financial statements may make it more difficult for an analyst to value a highly diversified entity, consolidated financial statements do provide a more complete picture of an economic entity than unconsolidated financial statements. The next section focuses on exactly how consolidated financial statements are prepared.

2 Consolidated Financial Reporting: Purchase Accounting

When a company decides to gain control over another, it can do so in several different ways: through a share purchase, a share exchange, or an asset purchase. In the first two approaches, the acquirer becomes the majority shareholder of the newly acquired subsidiary. Consequently, the subsidiary becomes a member of the parent’s family of companies. Under an asset purchase, the acquirer purchases only the operating assets (and possibly liabilities) of a company, but not its legal, organizational structure.4 Having sold its operating assets, the unaffiliated company is free, to do with its resources whatever it desires (such as go into another business or liquidate), subject to possible noncompete agreements.

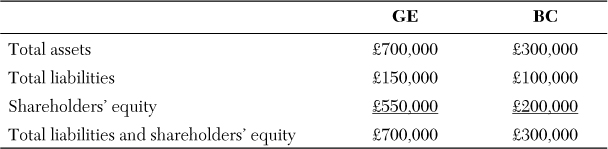

If an acquisition is executed by a share purchase, a share exchange, or an asset purchase, the purchase method (sometimes called “acquisition accounting”) must be used to account for the transaction. To help visualize how the purchase method is implemented, consider a simple acquisition between two independent companies.5 Assume that Global Enterprises Ltd. (GE) of the U.K. purchased 100 percent of the voting shares of British Company Ltd. (BC), another U.K. company, for £275,000 in cash. Immediately before the acquisition, the balance sheets of the two companies appeared as follows:

Assume further that the investment bankers GE hired to help assess the appropriate acquisition price for BC concluded that the fair market value of BC’s assets was £350,000, or £50,000 more than the book value of those assets. As a result, the fair market value of BC’s net assets (that is, assets net of liabilities) is £250,000. Thus, GE’s offering price of £275,000 is £25,000 higher than the fair market value of BC’s net assets. This amount, which reflects the excess of the purchase price paid over the fair market value of the acquired net assets, is called goodwill.

GE might be willing to pay a premium in excess of the appraised value of BC’s net worth for several potential reasons: the presence of a loyal customer base for BC’s products, a competent management team, an efficient distribution system, or anticipated cost savings and other synergies between the operations of GE and BC. Acquirers often pay a premium for the target, and as Chapter 1, “Valuation: An Overview,” mentioned that this premium commonly reaches 20 to 30 percent.

Immediately after the payment of £275,000 to BC’s shareholders, GE records its investment in BC as follows:

GE’s unconsolidated balance sheet then appears as:

Because the acquisition transaction took place between GE and the former shareholders of BC, the balance sheet of BC remains unchanged unless GE decides to use push-down accounting for its new wholly owned subsidiary. Under push-down accounting, the balance sheet values of the newly acquired subsidiary are restated to reflect the purchase price the acquirer paid to take over the subsidiary. In essence, the parent company imposes (or pushes down) a new cost basis on its new operating subsidiary. Hence, if GE’s investment bankers assess the fair market value of BC’s assets to be £350,000 and conclude that BC’s liabilities are fairly valued at their book value of £100,000, the fair market value of BC is £250,000. Under push-down accounting, BC’s balance sheet is revised as follows:

As a consequence of implementing push-down accounting, BC’s management now is expected to earn an acceptable rate of return on the fair market value of BC’s net assets (£275,000), a more difficult task than simply earning an acceptable rate of return on the historical cost of those same assets (£200,000). Most parent companies do impose push-down accounting on their subsidiaries for performance evaluation purposes and as a means of ensuring that the subsidiary managers operate on the basis of the same financial data as the parent’s management.

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) require GE to prepare and issue consolidated financial statements at the end of the fiscal year. To prepare its consolidated balance sheet, GE must transfer the recently purchased subsidiary’s net assets to its consolidated balance sheet. This can be accomplished with the following consolidation entry:

Note how the account “Investment in BC” is removed from GE’s unconsolidated balance sheet and replaced on the consolidated balance sheet by the specific assets and liabilities acquired, valued at their fair market value. Under purchase accounting, the subsidiary’s net asset value is “stepped up” to its fair market value at the time of consolidation, regardless of whether push-down accounting is imposed on the subsidiary.6

After the previous consolidation entry, GE’s consolidated balance sheet appears as follows:7

Before ending our discussion of the purchase method, a brief word about the consolidated income statement is necessary. Under the purchase method, the earnings of an acquired subsidiary are consolidated with those of the parent on a prospective basis only—that is, if an acquisition occurs at midyear, only those subsidiary earnings from the second half of the year (after the acquisition has been consummated) may be consolidated with the earnings of the parent. In essence, the subsidiary’s earnings from the first half of the year belong to the prior shareholders of the subsidiary and are not consolidated with those of the new owner.

3 Noncontrolling Interest

In the previous section, we considered the situation in which an acquirer company obtains a 100 percent ownership interest in a subsidiary. However, what accounting issues arise when an equity position of between 51 and 100 percent is acquired? To comprehend the accounting issues under these circumstances, one must first understand the full consolidation approach. Most countries use the full consolidation approach, which is premised on the notion of “control.” Under this method, even though a parent does not own 100 percent of a subsidiary, all of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are consolidated with those of the parent under the supposition that the parent controls 100 percent through its voting majority.

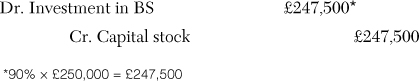

To illustrate the full consolidation approach, we return to the example of GE acquiring BC However, we assume that GE obtained only a 90 percent shareholding in BC by means of a share exchange. GE’s 90 percent investment in BS is recorded in the GE accounts as follows:

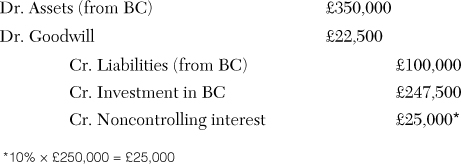

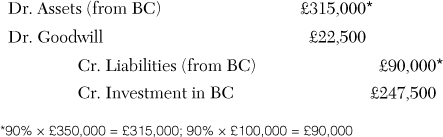

In anticipation of the preparation of consolidated financial statements, the following consolidation entry is executed in GE’s accounts:

Notice that GE records 100 percent of BC’s assets and liabilities on its consolidated balance sheet, despite the fact that, legally, GE owns only 90 percent of BC. As a consequence, it is necessary to create a new balance sheet account, the noncontrolling interest account, to represent the portion (10 percent) of BC’s consolidated net assets that does not belong to GE but to a third party. The noncontrolling interest account is sometimes referred to as the minority interest account and is often disclosed in the shareholders’ equity section on U.S. consolidated balance sheets.

After the above consolidation entry, GE’s consolidated balance sheet appears as follows:

Observe that the noncontrolling interest account appears as a credit balance on GE’s consolidated balance sheet, although it is neither a debt obligation nor a component of shareholders’ equity. It is merely a balancing account required under the full consolidation approach.8 Of some debate is how the noncontrolling interest account should be treated when calculating financial ratios such as the debt-to-equity ratio. Most practitioners either consider the noncontrolling interest account as a component of debt or exclude it altogether when calculating the debt-to-equity or similar financial ratios.

4 Accounting for Goodwill

Another consideration in our review of consolidated reporting practices involves accounting for goodwill under the purchase method. As already noted, goodwill arises when one company purchases another and pays more than the fair market value of the acquired company’s net assets. We return to our original example of GE acquiring a 100 percent shareholding in BC by purchasing shares from BC shareholders for £275,000 in cash. An analysis by GE’s investment bankers indicated that the fair market of BC’s net assets was £250,000. As a result, the acquisition transaction involved goodwill of £25,000, which was recorded on the consolidated balance sheet with the following entry:

After goodwill has been recorded on the consolidated financial statements, two prevailing approaches are used to account for it:

• Amortize goodwill against consolidated earnings over the expected useful life of the goodwill

• Do not amortize goodwill but subject it to an annual impairment test

With respect to the first method, the only difference in accounting for goodwill among countries using this approach is the length of time typically assumed to be the useful economic life of goodwill.

The second method requires that goodwill be capitalized on the balance sheet following the acquisition but does not require any periodic amortization of the capitalized goodwill. Instead, the goodwill is subject to an annual impairment test. If, and when, goodwill is determined to be impaired, meaning that the benefits associated with the acquisitions have either decreased or disappeared, it must be written down against earnings. This approach was adopted in the United States in 2001 and is also required under IFRS.9

For many analysts, goodwill is an asset of questionable value. For instance, most lenders write off the value of any goodwill to arrive at the company’s “borrowing base,” or what is commonly referred to as the company’s tangible net worth (shareholders’ equity minus goodwill). If goodwill is a legitimate revenue-generating asset, its value should be embedded in any pro forma projections of a target’s future revenue stream. Thus, it is important for an analyst to understand what goodwill represents to assess whether quantifiable benefits are indeed associated with the acquisition. If so, the value of these benefits should be appropriately reflected in any valuation estimates. Although the value of goodwill is not directly included in earnings-based and cash flow–based valuation methods, it is indirectly considered when forecasting the company’s future earnings and cash flow streams.

5 Tax Considerations of Mergers and Acquisitions

Consolidation practices for income tax purposes vary considerably around the world. In the United States, for example, when consolidated tax reporting is permitted—and considerable restrictions exist—companies often file consolidated tax returns to take advantage of operating loss carryforwards or tax credits from unprofitable subsidiaries to shelter the earnings of other profitable subsidiaries. Other countries, such as Canada, do not permit consolidated tax returns. Instead, each company must file its own tax return and pay its own income taxes. Globally, international consolidated tax returns are never permitted as long as the foreign subsidiary has a legitimate business purpose. In essence, all foreign subsidiary income is taxed in the country in which it is earned, unless the subsidiary has no legitimate business purpose—in that case, the income may be taxed in multiple countries.10

A result similar to foreign income consolidation is often reached if the parent company is incorporated in a country with a rule similar to the U.S. controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rule. Under the CFC rule, some or all of the net income of a foreign subsidiary that qualifies as a controlled foreign corporation is taxed to the U.S. parent corporation as a “deemed dividend,” taxable in the year earned rather than in the year repatriated. These rules arise because, in an attempt to escape or defer taxation, some companies have established subsidiaries in low- or no-tax countries called “tax havens” (such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Malta, and the Seychelles). Were it not for these rules, the parent company would succeed in transferring all or part of its profits from a high-tax environment to a tax haven by selling goods to these CFC subsidiaries at the lowest possible transfer price and then causing the subsidiary to resell at the highest possible price to the final customers. Under CFC rules, often called “transparency regimes” in countries other than the United States, the tax authorities of the parent’s country of residence evaluate the business role of each subsidiary. If a subsidiary is judged to be a mere conduit of goods or services (that is, it has no independent legitimate business purpose), such laws force the profits of the foreign subsidiary to be taxed in the home country of the parent as if a dividend of the profits had been paid to the parent company.

Under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code, a consolidated tax return may be filed only when the companies involved are U.S. companies and when the parent company owns at least 80 percent of the subsidiary. Furthermore, because the U.S. Internal Revenue Service does not recognize the equity method, U.S. companies rarely pay taxes on any income except self-generated income. The one exception involves dividends received from an affiliate or subsidiary. To avoid double taxation of these dividend earnings, the U.S. Internal Revenue Code allows an exclusion of up to 100 percent of the dividends that a U.S. parent company receives from a U.S. subsidiary. This exclusion does not apply to dividends that a U.S. parent receives from a foreign subsidiary.

Just as existing accounting rules can influence the structure of a merger or acquisition, the transaction can have income tax consequences. In the United States, for example, if a merger or acquisition is executed between an acquirer and a target’s shareholders—that is, the acquirer company either buys shares directly from the target’s shareholders or exchanges shares directly with the shareholders—the transaction is considered to be tax free to both the acquirer and the target. However, it is potentially a taxable transaction to the target’s former shareholders. As a consequence, even though the acquisition might be accounted for as a purchase for financial reporting purposes, the new subsidiary continues to calculate its taxes as it did before the acquisition; no step up in the value of the acquired assets is permitted, and, consequently, no additional tax depreciation is obtained. In essence, this type of transaction produces no particular tax advantages for the consolidated entity, unless the acquired company has operating loss carryforwards or unused tax credits. In contrast, if the acquirer buys the net or gross assets directly from the target and places the assets in a newly created subsidiary, the new subsidiary (and, indirectly, the parent) may claim additional tax depreciation on the stepped-up asset values implied by the transaction. Under this set of circumstances, the transaction is a taxable event for the target.

As this discussion suggests, tax regulations related to M&As can be quite complex and are almost certain to be country specific. Thoroughly reviewing these regulations is essential before executing a domestic or international merger or acquisition, to ensure an optimal tax outcome.

6 Tax Considerations of Goodwill

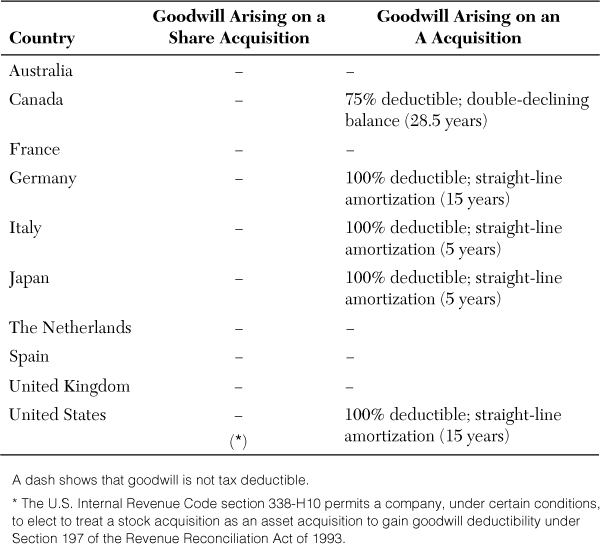

As illustrated in the vignette at the beginning of this chapter, an important issue in formulating the appropriate financial structure for an acquisition is the tax deductibility of goodwill. To help understand the existing tax regulations with regard to goodwill, it is necessary to differentiate between goodwill arising on a share acquisition, using either cash or shares as the consideration to acquire the shares of the target, and goodwill arising on an asset acquisition.

Exhibit 6.1 summarizes the tax deductibility of both types of goodwill for a selection of countries. Note that goodwill associated with a share purchase is not tax deductible in any country, whereas goodwill associated with an asset purchase is tax deductible in Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United States, among other countries. In some countries, the deductibility of goodwill arising from an asset acquisition is further constrained by the requirement that the assets be purchased by one domestic company from another. In this way, the tax deductibility of goodwill is a tax-neutral event; the domestic selling company pays income taxes on goodwill, and the domestic buying company gains a tax deduction for the goodwill, all within the same country.

Summary

Summarizing the key issues for such a complex topic as the financial reporting and tax considerations of M&As is difficult. It is perhaps most useful to organize a summary around the five key questions that need to be addressed in anticipation of a merger or acquisition:

1. Do local accounting standards require the preparation of consolidated financial statements?

2. How was the transaction structured financially—as a share purchase, a share exchange, or an asset purchase?

3. If purchase accounting is required, is goodwill present in the transaction?

4. Was a 100 percent ownership interest obtained?

5. What accounting and tax treatments for goodwill are permitted under local accounting standards?

Endnotes

1. “Tax Conquistadores,” Financial Times, 11 October 2007.

2. For our purposes, a majority-owned subsidiary is one in which the parent’s voting shareholding exceeds 50 percent.

3. The implications of this practice can be far reaching: If a parent company wants to consolidate a recent acquisition, it can arrange to execute the acquisition at the parent level, whereas if the parent wants to avoid consolidation, perhaps because of a subsidiary’s high level of debt, the acquisition can be executed by an existing or recently created, but unlisted, subsidiary. Thus, in some countries, a parent company can exercise considerable discretion in accounting for a merger or acquisition by controlling the organizational level at which an acquisition is executed.

4. One advantage of the asset purchase approach is that an acquirer can limit its purchase to the specific assets that it wants to own or control. However, an asset purchase can also be quite broad in scope, encompassing both the assets and liabilities (or net assets) of a company. When the net assets of a company are acquired, the acquirer also assumes responsibility for settlement of the subsidiary’s liabilities, a factor that reduces the total price paid for the purchased net assets.

5. The assumption that the two companies are “independent” is important. If the two companies are not independent—that is, if they engaged in various intercompany purchase or sale transactions, or borrowed or lent money to one another—any intercompany transactions must be eliminated before preparing the consolidated financial statements. Elimination entries avoid double counting of any intercompany profits and eliminate nonsensical items such as a receivable from (or payable to) the consolidated entity itself.

6. Occasionally, when the book value of a subsidiary’s net assets is overstated relative to its fair market value, it is necessary to “step down” the subsidiary’s net asset value, to write the subsidiary’s net asset values down to their lower fair market value. In some countries, an alternative to stepping down the subsidiary’s net asset value is to value the subsidiary at its overstated book value and to also record negative goodwill (a credit balance) for the amount by which the subsidiary’s net assets are overvalued. This latter alternative is not permitted under U.S. GAAP but is permitted under IFRS and the accounting standards of many countries. For example, Germany allows companies to carry negative goodwill on the credit side of the balance sheet and to amortize (add) it to the consolidated net earnings over time (usually 5 to 15 years); alternatively, a company may immediately add the negative goodwill to the parent’s equity reserves.

7. If, instead of a share purchase, GE purchased 100 percent of BC’s net assets (BC’s assets and liabilities, but not its legal corporate structure), the following entry would be recorded in the GE accounts at the time of the net asset purchase:

GE’s consolidated balance sheet would appear as follows:

Thus, whether an acquisition is executed as a share purchase or as a net asset purchase has no effect on the final consolidated financial statements; the consolidated statements appear the same under both approaches.

8. A simpler methodology that does not require creating a noncontrolling interest account is the proportionate consolidation method. Under this approach, a parent company consolidates only the value of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities that it actually owns. To illustrate, continuing the previous example, GE’s consolidation entry would appear as follows:

The partial consolidation approach is intuitively easier to understand and eliminates the need for the noncontrolling interest account. However, most members of the financial community believe that control is a far more important criterion than ownership. Thus, the proportionate consolidation method is not widely used globally, except when accounting for joint ventures.

9. A little-known accounting rule in the United States effectively allows an acquiring company to minimize the amount of goodwill ultimately booked after an acquisition, an outcome similar to the write-off–to–equity method. The accounting rule in question permits an acquirer to establish a fair market value for the in-process research and development assets at an acquired company and to immediately write off that amount. The higher the value assigned to the in-process research and development, the lower the value that ultimately must be assigned to goodwill on the consolidated statements. This accounting rule can be particularly important for acquisitions of high-technology and pharmaceutical companies, which often have a significant level of research and development expenditures.

10. If a parent company conducts operations in a foreign country, as contrasted with operating an independent subsidiary in the foreign country, any foreign income is subject to taxation in both the foreign country and the home country. In this case, any foreign income is consolidated with a company’s domestic income for purposes of assessing taxes due in the home country. To avoid double taxation, the home country usually gives the tax-paying company a tax credit for any foreign taxes paid. Thus, if a U.S. company conducts operations in Hong Kong, where the statutory tax rate is 16.5 percent, any foreign earnings are subject only to a further incremental 18.5 percent in U.S. taxes (the U.S. statutory tax rate is 35 percent, hence 35 − 16.5 = 18.5). Alternatively, if the U.S. company conducts operations in a foreign country where the statutory tax rate is higher than 35 percent, no further U.S. taxes are levied on the consolidated income from that country. However, the company cannot receive a tax credit (against U.S. taxes) for any tax payments it made in the foreign country above the U.S. statutory rate. As of 2012, the United States has one of the highest statutory tax rates in the world.