Chapter 1

How “Real” Is the Value of Cloud Computing?

Try not to become a man of success but rather try to become a man of value.

— Albert Einstein

We defined the value of cloud computing 20 years ago…and have kept redefining it ever since. It’s become a source of confusion among those who must explain the value of cloud computing in the form of a business case.

In this chapter, we look at how we initially defined the value of cloud computing, how and why it changed throughout the years, and the current reality of “cloud alue.” We also talk about what’s just pure junk science.

What We Thought We Knew

The value of cloud computing is perhaps one of today’s most debated topics in the world of business technology. We made many assumptions when cloud computing first became a hyped technology concept. Much of our initial thinking about the value of cloud computing got hit in the face with reality when most businesses did not realize those anticipated values, at least, not in ways the values were originally defined and promised.

This failure to recognize values led to serious reevaluations around how to define the true value of cloud computing. We based these new assumptions and metrics on the values businesses see in terms of increased revenue, higher stock prices, and, in some cases, the movement companies could make to dominate their marketplaces in a true disruptor fashion, much like Uber, Amazon.com, Netflix, and others that leveraged cloud computing as a true force multiplier.

Back to our first thoughts about cloud computing, we saw value in the ability to get out of the business of owning and operating hardware, software, and data centers. Most stakeholders understood the value that computers could bring to a business in terms of automation and data management, but the costs of owning the hardware and software were prohibitive at the time. They also took notice when the business needed a new system to automate a process or store data, and the result was many millions of dollars spent on new servers, storage systems, power supplies, and data center space, as well as the group of people needed to maintain everything.

This cycle prompted the computing industry to take another look at the time-share model, which was how businesses initially consumed computing in the early days of automation. Back then, many companies offered time-sharing services that could leverage powerful (at the time) computing and storage systems, and clients would pay only for the time that they remotely leveraged the computers. As a result, the cost of owning a physical system experienced a significant drop.

New innovations such as minicomputers and then the personal computer, along with local area networking (LAN) and wide area networking (WAN), opened new possibilities. It became more advantageous to the business to own your systems. After the initial investment, you had unlimited access to compute and storage systems that you owned and depreciated.

The Return to the Utility Model

In basic terms, today’s move to cloud computing is simply a return to the old utility model of time sharing. The ideas are the same: You leverage a system that’s offered and maintained by somebody else, and you pay only for the resources you use.

This approach is much like we leverage other utilities, such as electric power for our homes and city water services. Yes, we could leverage power from our own eclectic generators, or we could dig a well. When you weigh the initial investment required, it’s usually more cost effective in cities and suburbs to purchase these services from centralized providers and tap into their existing infrastructure.

Of course, cloud computing is much more sophisticated than traditional time sharing, considering that we now leverage remote systems via broadband networks. We can do so as if we own the systems rather than leverage yesterday’s tightly controlled and managed services. However, the consumption models of yesterday and today are very much alike. Both are metered services where you pay only for the resource you leverage and the amount of time you leverage it.

How did cloud computing drive our return to the utility model? Here are the influencing factors:

Today we better understand the value that businesses put on capital. We once considered millions of dollars’ worth of computing equipment and data centers just part of the cost of doing business. These days, businesses eye those investments as capital boat anchors that do not allow them to fund areas of the business with a higher ROI potential. For example, the purchase of another company could provide better channel access to the market, or businesses might spend additional money on innovation that could result in unique differentiators that enable the business to become a market disruptor.

When another company provides core operational services, that frees up the costs of hiring and maintaining those skills. When businesses went into the systems operations business, the number of people needed to operate those systems exploded. Staffing costs leapfrogged to include hard-to-find and costly skill sets.

The value of moving to a more innovative state through the use of technology. Today, most innovation happens in the cloud. If you want to leverage best-of-breed, then you’re on a forced march to the cloud: It’s where you’ll find the most effective and efficient best-of-breed technology. Databases, security, development, and operations are all state-of-the-art within public clouds such as AWS, Google, or Microsoft. This is where vendors made and will continue to make most of their research and development (R&D) investments.

The Elusive “Cost Savings”

“Cost savings” was the initial battle cry of cloud computing for good reasons. Until then, most Global 2000 companies built their own data centers and filled them up with expensive and quickly depreciating hardware and software. This led to IT departments that grew much faster than the revenue to justify the growth. Soon everyone wanted to get IT costs under control and align IT spending more closely to the minimum values that stakeholders required from their IT investments.

Around the end of the 1990s, enterprises saw an opportunity to get out of the IT cost spiral. We could no longer spend $2 and project $1 in returned value. Something needed to change. The time was ripe for a fundamental shift in the way that we built, deployed, and leveraged applications and data. Along came the time-share model in its new incarnation.

Most in IT understood the legacy time-share model, although we had a more intermediate step in the ’90s known as application service providers, or ASPs. These differed a bit from modern Software as a Service (SaaS) providers. Basically, they were off-the-shelf software programs that ran over the newly emerging open Internet, and just became a host for applications you would normally run in-house. Since these applications were not purpose-built for use by multiple users over the Internet, scalability and performance were problems often reported by those who leveraged ASPs. Also, the ASPs did not utilize modern mechanisms that you find in today’s clouds, such as virtualization in support of multitenancy.

However, ASPs had the same value proposition as modern cloud computing. ASP value included cost savings, easy upgrades, and payments only for the time that you leveraged the applications and data. In other words, these were the first early tries at cloud computing. At the time, they fell short in what could be delivered. The desire to find a new consumption model for technology remained, with the same cost-reduction battle cry.

SaaS, such as Salesforce.com and others, showed up shortly after the ASP market tanked. There were several differentiating and attractive factors that favored the early SaaS providers. The applications were purpose-built to be multitenant products that could support the ability to service thousands of simultaneous users. They could scale to the processing loads that the customers required. They maintained a good uptime record, and even offered better security than was currently available with traditional on-premises applications.

Thus, SaaS (initially called “on-demand applications”) paved the way to Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) and Platform as a Service (PaaS). The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defined and standardized both terms around 2008, which led to today’s “official” cloud computing definitions that include private clouds, public clouds, community clouds, and hybrid clouds.

It’s Not CapEx Versus OpEx, and It Never Was

The goal here is to provide a brief history of cloud computing. It’s important to understand where we started and how our thinking evolved around cloud cost savings (value). It’s also helpful to understand why our initial definitions of the business value of cloud computing completely changed over time.

Back to CapEx versus OpEx (see Figure 1-1). The shift to OpEx from CapEx initially appeared on the scene as a hyped technology change. Most businesses viewed OpEx as the means to realistically define cloud computing’s business value. OpEx changed the way we consumed computing and IT in general, which in turn provided the ability to get IT costs under control. These approaches seemed logical at the time, and OpEx became a prominent presentation point by those who promoted the use of cloud computing at the time.

FIGURE 1-1 In the early days of cloud computing, the idea was to adopt operational expenses (OpEx) and thus reduce Capital Expenses (CapEx). This proved to be a wrong assumption.

The argument was sound. Reduce the amount of money spent on traditional computing systems and data centers and free up that capital to put back in the business. The trade-off would be a shift to operating expenses that aligned to usage. The more IT resources we used, such as storage and compute, the more we paid. This was known as “being elastic” in terms of scaling up and scaling down and increasing and reducing costs to fit current needs.

Sadly, most real-life cloud computing experiences challenged the CapEx versus OpEx way of thinking about cloud computing value.

Any quick web search will reveal that cost overruns around cloud migrations and cloud operations became the norm. The reasons vary when you ask what went wrong. The answers come down to two core issues: first, unrealistic expectations about where to find the value of cloud computing; and second, incorrectly defined metrics.

This Is About Business Value, and It Always Was

Here’s a hard reality: Most of the benefits we see from the use of cloud computing are not in operational cost savings or from saving capital for more strategic uses of the funds. It’s about cloud computing’s transformative business value. Transformative business value is much more viable than any CapEx versus OpEx set of metrics would have you believe. It’s also more difficult to understand. Basically, we can call this “hard” versus “soft” business value.

Hard value is easy to determine. Let’s say the use of cloud computing saves us 10 percent in operational savings, such as using storage and compute from AWS, Microsoft, or Google, versus from our own hardware in our own data center. What we often fail to factor in are new skill sets, including the additional costs of those skills. Additionally, many of us don’t fully understand or correctly plan for the costs of data ingress and egress to and from cloud providers. Moving enterprise data to and from on-premises data storage to cloud-based data storage typically involves a fee each time you do it. Usually, by volume.

Other issues arise around hard costs when the staff does not understand why things cost more than expected, which includes the costs of inefficiency. If you don’t understand why it happens, how will you prevent it from happening? These are the costs that enterprise IT shops encounter when they do not have a good handle on management of new cloud costs, such as storage, compute, databases, and artificial intelligence. Indeed, prepare for sticker shock when you see what happens when resources are allocated and then not deallocated, or, more common, when things are just more expensive than first estimated. For instance, if the costs involved of expanding and changing the use of technology were not originally understood.

Soft value is where we should define the real value of cloud computing from the beginning. However, the term soft comes from the fact that we’re defining value as something that’s hard to determine—for example, the value of business agility, speed to market, and the real value of market differentiating innovation (see Figure 1-2).

FIGURE 1-2 The true business value turned out to be more difficult to measure, such as the value of agility, speed to market, and innovation.

While most will agree that these soft values are more advantageous to the business than any operational savings that cloud computing can bring, we also agree that these values are difficult to determine. If I tell you that cloud computing will provide more business agility, your natural responding questions would be

What’s business agility?

What’s the value of increased business agility by product line?

How do we measure the success of having more business agility?

How do we know if the value of business agility cost justifies cloud computing in the first place?

Same goes for speed to market and innovation. Most will struggle to define these spongy concepts for a specific business. Let’s try to create a set of approaches to define the worth of these soft values.

Note

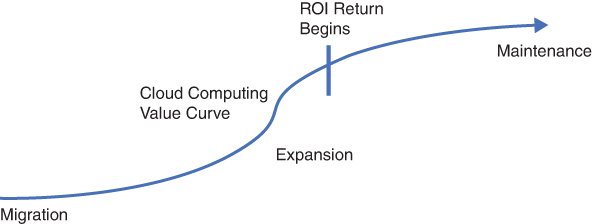

There is an investment being made with new value returned during the initial migrations to the cloud. Then there is an increase in value as expansion begins and the enterprise realizes the soft values we define here, values that include business agility, speed to market, and innovation. All these values will increase by using cloud computing. Eventually, there is a move to the maintenance stage when the move to cloud slows down and the enterprise focuses on continuously improving the cloud services in support of the soft values.

Figure 1-3 shows a typical value curve that most businesses see when they implement cloud computing. Notice that the curve is not a straight line; instead, it inflects around the midpoint when the enterprises get about 30–40 percent of the applications and data sets migrated to the cloud. Of course, at some point the value diminishes as the technology moves into more of a maintenance mode.

FIGURE 1-3 The cloud computing value curve shows where the return is equal to or greater than the amount invested, which is typically farther down the path than most businesses understand at the outset of a cloud project. Indeed, for most businesses, cloud computing has yet to return the values that were advertised in the early days of cloud computing.

Agility

Business agility, or just “agility,” is the business’s ability to change around business requirements. Examples of agility include moving into new markets via an aggressive acquisition strategy, where key business processes and data need to be quickly integrated. Or, adding a new “game-changing” product such as a traditional core manufacturer adding a line of electric vehicles. Agility includes anything that has a value multiplier if these improvements can quickly be placed into production and thus drive more revenue, and even improve stock prices.

The trouble with agility is that you don’t know what the value will be until you see the effects of the system’s ability to drive more agility. Therefore, we must rely on estimates around what we think the value of more business agility will bring. This means doing complex modeling that considers many different factors that make up the value of business agility estimations. Of course, some of these assumptions, such as market acceptance as a factor, may not turn out to be correct.

To predict the unpredictable, you need to determine a best- and worst-case scenario. What is the value of agility if all assumptions are correct, meaning they meet or exceed estimates? Or what is the value if the assumptions fall short? For instance, we assumed that an emerging market could be found in a specific area, such as robotic lawnmowers. However, the market was slow to grow due to an economic downturn where luxury items such as lawnmower upgrades saw diminished demand (worst case). Or, just as likely, the cost of gas skyrocketed to a point where electric lawnmowers are seeing demand that outpaces initial estimates (best case). Most of the time, the reality will fall somewhere in between.

Keep this in mind: Increased agility returns huge values for most enterprises. However, the degree of value will greatly vary from one enterprise to the next, and with how they can or want to weaponize business agility to find more markets and thus revenue.

It will take some creative thinking to figure out the soft value of agility in your enterprise and how cloud computing can enhance its business agility. How you understand your business and create these estimates will also come into play. Each business will have a different value for business agility and a different way that you determine what you think that value will be.

Basically, the more value you place on business agility, the more valuable cloud computing will be to your business. Indeed, the value of business agility will be many times that of any investment in cloud computing. Operational savings should not be the main consideration, or sometimes no consideration at all when your enterprise looks at the true value of cloud computing. This is a value indicator that we missed back when cloud computing began.

Speed

Speed is a bit different than agility, but kind of the same. Speed focuses on your ability to move fast in a single business direction, whereas agility focuses on your ability to change your business fast.

Like agility, speed (such as speed-to-market) will have various degrees of value that depend on your business and the markets you serve. For example, a box factory in the Midwest might place a very low value on speed. The market demand for boxes usually doesn’t change with enough velocity to put a premium on moving fast.

However, another company will place a very high value on its ability to expand production of a product based on current or projected explosive demand. A simple example would be a trending children’s toy at the onset of the holiday season. Cloud computing allows the enterprise to scale up production processing to much higher levels, which will increase the speed of production to meet changing demand. Thus, the enterprise obtains more revenue. Therein lies the soft value of speed-to-market, which usually exists within the value of agility.

Innovation

Innovation is perhaps the most underrated value of cloud computing. It often gets overlooked for the same reasons that speed and agility get overlooked. Determining its value is also just as difficult. Putting a dollar figure on innovation will take much deeper analysis to predict, specifically what value innovation will bring to any individual enterprise.

With that said, the value of innovation is relatively easy to understand. For example, Uber used innovation to figure out how to create one of the world’s largest transportation and delivery services, and it did so without owning a single vehicle. Cell phone manufacturers took the innovation leap to make small and powerful computer systems that now fit in our pockets. Innovative leaps by these companies now define most if not all their value in the marketplace, and they had to effectively leverage technology to get there.

Cloud computing supports innovation by giving enterprises cheap and almost instantaneous access to technology. In the relatively recent past, it would have cost several million dollars to access AI to drive innovation in your company. Today, cloud-based AI systems are much more advanced than the AI technology of just 10 years ago, and AI might cost only a few dollars a month to run. Even better, you can leverage today’s AI by just clicking a box on a public cloud provider’s dashboard.

The same can be said for very large analytical databases, advanced processing systems such as high-performance computing (HPC), the Internet of Things (IoT) development, edge computing development, containers, and anything else the innovator wants to create that could launch the company to a different competitive level.

Indeed, almost all of today’s innovations occur in the cloud, and have since about 2015. Those who build and deploy this technology understand that the market they need to build for is “the cloud.” It’s unsurprising that enterprises spend almost 90 percent of their R&D dollars on cloud-based technology rather than on traditional systems. This is the reason that security, operations, governance, databases, and AI systems are now better in the cloud than on premises. This will remain the case for the next few decades.

We know that most businesses place a high value on innovation, but how high is it for your business? This typically depends on the following business attributes:

The market that your company falls within. For instance, an enterprise in the finance vertical will typically gain much more for key innovations than an enterprise would gain in the agriculture vertical. Take our box company example mentioned previously. It’s a sound business, but it’s doubtful the company would gain a great deal from innovative capabilities around improvements to boxes. It’s a different story for tech company disruptors. (Not to pick on the box industry as noninnovative; it’s just an example.)

Your current position in the market. Innovation is more valuable to larger companies with an existing market and customer base. The bigger you are, the more you must gain from innovation. Conversely, big companies are known for driving less innovation than their smaller counterparts.

What are the most likely innovations? In some instances, companies redefine themselves through net-new innovations. For instance, a boat company invents a new way for boats to float above the water using an innovation around magnetic levitation (MagLev). This is an innovation that falls outside of traditional offerings with net-new technology that could disrupt the existing boat market and create a net-new market that does not yet exist. Others may create innovations that are not as game-changing. An automotive parts manufacturer might create brakes for cars that last two times as long as traditional brakes. Innovative, yes. But not revolutionary.

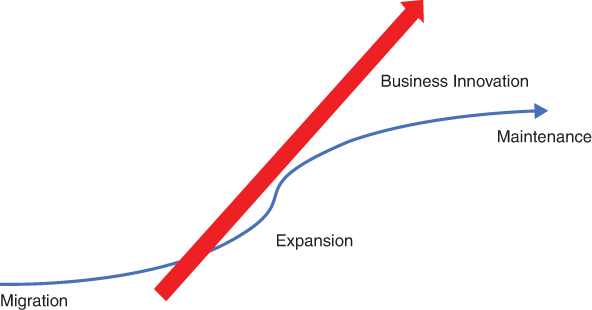

Figure 1-4 shows how innovation value may appear in the cloud value curve we introduced previously. In this model, innovation driven by cloud adoption significantly increases, well behind the rate of cloud adoption. Depending on the business attributes listed previously, your curve may not be as steep, or it might only slightly slope up. The key here is to understand the true value of innovation. Not just in general terms, but how the true value of innovation relates specifically to your business.

FIGURE 1-4 A core value that cloud computing brings is the ability to drive business innovation. This means that companies can become disruptors rather than be disrupted.

How do you define the soft values of cloud computing for your enterprise? Here are a few recent schools of thought:

What are the differences in values between the business having the soft values of agility, speed, and innovation in place and not in place? What are the values minus the costs of migrating to the cloud, including all migration, development, and operational costs? For example, if the business does not have cloud computing in place to support these soft benefits, what is the sell-price value of the business? Now, what is the value of the business if these soft benefits are enabled using cloud computing? We can call this the “value differentiator calculation” to determine true value.

Define and project the increase in revenue by putting these soft values in place using cloud computing. Let’s say a business experienced revenue at 6 times all costs in 2010. When the business migrated 50 percent of the applications and data to the cloud by 2015, they experienced revenue at 14 times all costs that included migration and operational costs of the new cloud-based systems. Now you can assume that the use of cloud-based systems, including the accompanying soft values, will produce 8 times more revenue.

Here we say “assume” because other market factors could drive sales up or down by increasing or decreasing the company’s ability to sell more goods and services. Some simple market factor examples are the pandemic and current gas prices that were unforeseen a year before they happened. Both events drove businesses both to and away from certain markets. In this context, think about the production of face masks versus office furniture, and the production of electric cars versus RVs. This quickly becomes a complex calculation that should factor in as many variables as possible. Thus, this example might not be a good determination of value, considering that we’re only looking at revenue differences rather than considering the true value of the business, or what you could sell the business for at any given time.

The way you define the value differences will always be unique to your business, either estimated prior to moving to the cloud when creating a business case or when evaluating the post-value benefits after cloud systems are in place. I could present any number of formulas and metrics here, but none will apply to your specific business.

Yes, you could make incorrect assumptions if you force fit someone else’s idea of a value calculation to your business. While you can certainly use the value calculation concepts in this book as a starting point, your best bet is to form your own ideas and models based on the needs of your actual business and your understanding of their values.

What Could Go Wrong?

Taking another step back in time, if our first ideas around defining the value of cloud computing were mostly wrong, what exactly went wrong and what exactly went right? I always think it’s a good idea to figure out what did not work and why. Don’t just ignore a failure and hope nobody notices. The reality is that we’re wrong a lot about the true value of technology, and we need to focus on how to make better technology value assumptions moving forward.

This is not about pointing blame at the many who promoted cloud benefits as just an OpEx versus CapEx, including promises of lower operational costs. Today, we need to find the true value of cloud computing and admit where these value concepts can be improved. Generally speaking, let’s look at what went wrong.

Too Much Focus on Operational Cost Savings That Seldom Became a Reality

For many businesses, cloud computing can provide operational cost savings. However, clearly the industry overpromoted the concept of operational cost savings at the onset of cloud computing.

A variety of unconsidered things happened. An example would be not accounting for the higher costs of public cloud services that ended up being the services leveraged versus the basic cloud services that defined the initial value.

We often priced the use of cloud services using simple storage and compute service prices to support migrated applications with analog platforms (e.g., Linux on premises versus Linux in the public cloud).

Tempting new services and enabling technology in the cloud soon arrived, adding costs, but were too tempting to ignore. These included AI and machine learning, advanced databases, serverless computing, edge computing, IoT, containers, and any number of technologies the tech press promoted over the last 10 years.

While the use of these technologies by migrated and net-new applications significantly raised the cost of public cloud computing for most of those use cases, it was the right call to make. By focusing on the soft values I described earlier in this chapter, the value and use of these emerging technologies easily offset the higher operational costs. For many companies, the use of these technologies and the pragmatic innovation they provided “made” the company. This is certainly the case with better known disruptors such as Uber, Airbnb, Netflix, and other companies that quickly learned how to weaponize cloud computing. Often, the amount of time taken to migrate a service to the cloud ends up being double or triple the time that is first estimated. This increase is due to a lot of reasons, but the majority of the time it’s simple poor migration planning. Moreover, the client is paying for the legacy system and the new cloud environment at the same time.

Even though the cost of cloud computing turned out to be much more than we initially thought, those who made the decision to pivot to the types of cloud technology where they found more exponential value often found more soft values. They made the right decisions. It all depends on the specific business. It’s more impactful for some businesses to place more weight on the soft values that cloud computing brings than it is to stick to a static cloud computing budget. Sometimes it’s not.

Too Little Attention Paid to the Cost of Skills

The cost of good people with good cloud skills turned out to be a whole lot more expensive than we once thought. In 2010, a cloud computing specialist or an experienced consultant cost about $35–$45 USD per hour, or about $80,000 per year if salaried. That person had general cloud computing skills, such as understanding cloud storage, cloud compute, and the configuration of cloud platforms. There was very little specialization when cloud computing first appeared, and most “cloud people” were generalists.

Today, it’s a seller’s market that does not seem to be affected by the existing unemployment rate. If you’re a cloud computing generalist in 2023, you’ll likely make at least $75 USD per hour, or about $140,000 per year in salary. However, if you’re a specialist and focus on specific technologies such as data analytics in the cloud, AI, or machine learning, or if you are a cloud computing architect, then the salaries and hourly rates carry huge premiums. It’s not unusual for a cloud technology specialist with specialized certifications (such as those provided by the larger cloud providers—AWS, Microsoft, or Google) to command $200 per hour, with salaries well over $275,000 on the top end.

Remember, you make and pay the market rate for talent. It turns out today’s costs for certain skills are at a much higher premium than many anticipated in the budget phase. Indeed, the current cost of talent is often the highest cost of moving to the cloud or building systems in the cloud, with the actual cloud costs being a much smaller portion of the budget.

The higher salaries and rates just confirm that cloud computing skills are in demand since cloud computing is in demand. This demand is largely due to businesses finally figuring out the soft values I described here. Even these higher salaries are a drop in the bucket compared to the overall value that most businesses can find when they use cloud computing services.

Cloud Providers Thrive on Profit

Many focus on greed as a primary reason that cloud costs are too high, whether that greed involves the cost of skills that I just described or the cost of cloud computing services themselves. What’s clear is that cloud computing providers are in business to make money, just as your company is in business to make money. As such, providers will drive as much profit as they can, and that will reflect in higher fees and fee structures as cloud computing matures.

These prices do not surprise anyone who has been in technology longer than a few years. Nor did it surprise us when many of the large enterprise technology players jacked up the license fees for their older technology. These databases, platforms, legacy hardware, and other systems that enterprises once depended on are now legacy technologies that vendors won’t further improve. Today, technology providers focus almost exclusively on cloud products.

The days of watching public cloud prices drop are at an end. Don’t be surprised that the cloud providers now want to maximize the returns on their technology investments. The cloud providers will charge clients the value that they believe they bring to the business. These costs will in turn drive more profit for the cloud computing providers.

Today’s new technology offerings come with new and higher prices. Volatile prices add a new dimension of difficulty to planning for hard and soft costs. However, if higher cloud costs also increase business value, the costs become more of an observation than an obstacle.

What Went Right?

On a more positive note, let’s turn our attention to what went right. It’s important to understand what assumptions came true to find the true value of cloud computing. Here “in the right,” we can determine the true value of cloud computing. We can also identify the true value drivers and pivot to support new patterns of thinking about value. It’s all about focusing on the soft values we covered previously.

Cloud computing is still an evolving technology, which means we will redefine cloud value for years to come. However, much of what we cover in this chapter will evolve as well, albeit I suspect the same soft values will remain consistent for at least the next 20 years.

Agility, Innovation, and Speed Become King

As we covered earlier in this chapter, today’s end state understanding of the value of cloud computing seems to focus on the value of agility, innovation, and speed. Because we already covered these soft values in detail, we do not cover them again in this section. Instead, let’s review how we concluded that these were the right soft values to focus on.

Many businesses have different motivations to leverage cloud. For some, such as startups with little funding, cloud computing was their only option. They could purchase powerful computing resources at reasonable prices and forgo yesterday’s requirements to spend millions of dollars on data center space, hardware, software, and people to run everything. These companies had “no choice” but to move to the cloud. Even companies that were built in the cloud served as nice use cases for those still trying to figure out the business value and how to migrate to the cloud.

The unique factor about startups “born in the cloud” is that their motivations to utilize cloud computing back then echo the reasons that enterprises should leverage cloud now. What often differs is that these startups also enjoyed OpEx savings. They had no existing data centers. Cloud was cheaper, and they paid only for what they used, which directly aligned to the revenue that the cloud-based systems brought back to the business.

While this direct alignment to usage and revenue was certainly true for most smaller or startup companies, enterprises did not share the same experiences since such a small portion of their IT systems were cloud-based systems, and thus it was difficult to determine the amount of revenue a cloud system generated at different levels of use.

For example, let’s say a .com startup keeps all web and revenue-generating systems on a public cloud provider, say AWS. If the startup gets a cloud bill of $1,000 for a single month and sees $100,000 in revenue to show for that bill, and the next month’s bill is $2,000 and there is $190,000 of revenue that month, it’s easy to draw a direct correlation from the usage of cloud-based systems to revenue.

A larger company might see the same cloud bills from one month to the next. However, because it has only 10 percent of its systems migrated to public clouds, it’s difficult to figure out which systems, cloud or not, directly related to an increase or decrease in revenue. Worse, most larger enterprises don’t track revenue generation per system, cloud or not, so they don’t have the mechanisms in place to figure out how much revenue relates to any specific system, cloud or not.

You might think that smaller cloud users, including startups and other small businesses, would prove the initial thinking around CapEx versus OpEx values. However, a few things emerged around some of the startups that left the traditional business case assumptions in the dust and change the focus of larger businesses to the soft values we covered in this chapter.

Why? Well, many of the businesses that first leveraged cloud through economic necessity became industry disruptors and found that cloud computing was a better weapon than just a utility service. Netflix, Uber, eBay, PayPal, and Airbnb, all early adopters of cloud computing in their startup phases, learned quickly that cloud was much more than a money saver.

Keep in mind while these are the brands that most people trot out when talking about the cloud computing benefits of agility, speed, and innovation, thousands of other lesser-known businesses have found the same value. Many of those businesses are also industry disruptors with explosive growth. Or, they are about to disrupt an industry, such as prescription drugs, logistics and supply chains, insurance, home automation, and other industries where the current leaders proved less than innovative and agile.

In the end, customers will vote with their dollars just as they did with Netflix over Blockbuster Video, or Uber over any city taxi service. If you think these disruptions are at an end, think again. Over the next 10–20 years, we’ll see an entirely new crop of disruptor brands emerge. All will have the same two things in common: They will recognize the value of cloud computing technology, and they will weaponize it to dominate an industry.

Weaponization of cloud computing differs from disruptor to disruptor, but the primary values these disruptors found and will find in the cloud include

The ability to quickly adapt. For example, pivoting to new and more lucrative markets during the initial growth phase of the company.

The ability to out-innovate larger businesses. For example, the ability to leverage AI systems to provide a better customer experience.

The ability to scale without slowing down the business. Startups that leverage cloud computing could go from 100 customers to 1,000,000 customers with basically the same infrastructure. While their cloud costs rose, so did revenue to cover those costs.

The ability to keep up with market demand. As demand rises, startup disruptors that use cloud don’t worry about keeping up with changes in demand. They can both pivot and increase velocity as needed to support the business. Most of the time with the click of a mouse.

Best-of-Breed Put the Business Back in Control

Initially, cloud-based platforms were not best-of-breed in any way, shape, or form. They were just simple storage and compute solutions. As cloud evolved and became the focus of most R&D budgets, public clouds became the location where innovation occurred, and thus where the best technology could be found. This includes databases, application development, AI and machine learning, analytics, serverless, and containers, as well as upcoming approaches such as IoT and edge computing.

Those in the cloud had access to more innovative best-of-breed technologies to build and deploy their systems. Many of these systems became game-changing technologies that defined their business. Again, the successful disruptors learned how to effectively leverage this technology to support their business and to create a new space such as ride-sharing and house-sharing applications that are now industries worth multiple billions.

The unique part about this wave of change is that it put the control back into the hands of the business. In the past, most businesses depended on a handful of technology providers or whoever owned the platforms they leveraged to support their existing systems. Diverting from those primary providers meant higher costs and risk, which was typically not an option for most Global 2000 companies. Thus, best-of-breed from their providers was rarely best-of-breed in the marketplace because they were limited to a small pool of technology providers.

The rise of cloud computing opened the technology market for those committed to cloud computing. Because most technologies have a cloud-based version that exists within public clouds, those are now options as well. The key advantages here include easy and open access to the newest and most innovative best-of-breed technologies.

Because we’re no longer dependent on a specific technology that supports our existing traditional platform, we can focus on all technologies that we need or want to deploy. Any platform configurations can be done on public cloud providers; thus, there are no limitations that hinder what technologies you can leverage. That puts control back within the business that leverages cloud computing.

Technology providers spend about 90 percent of their R&D budgets to build technology specifically for clouds. Therefore, the newest and most innovative technologies are found in the cloud. Given the access advantages we just covered, this means there are no limitations as to what technologies we can leverage, and these technologies will be the latest and greatest.

The key theme here is control. No longer is a business stuck with whatever technologies worked with past platform decisions. Instead, businesses control all aspects of what technologies they leverage, how they leverage them, and can be certain that the best-of-breed technologies they need to meet business requirements can be found in the cloud. This is far more liberating than most people understand right now, but they will.

Security Is Better in the Cloud

Security was the most common argument against cloud computing, certainly public cloud computing, and it’s a criticism that you’ll still hear today. I once called this “hug your server” paranoia. Public cloud providers use data centers that you’ll never see or enter. How can your data and systems be safer if you can’t physically see or touch (“hug”) the hardware it runs on?

Around 2014, those in the know noticed a shift in security offerings. Again, most of the technology providers’ R&D budgets are now spent in the cloud. This spending includes development of new and innovative security solutions. Cloud providers spent and will continue to spend an enormous amount of money to shore up their native security offerings. Many cloud experts, including myself, have declared that cloud computing systems are now more secure than most traditional systems.

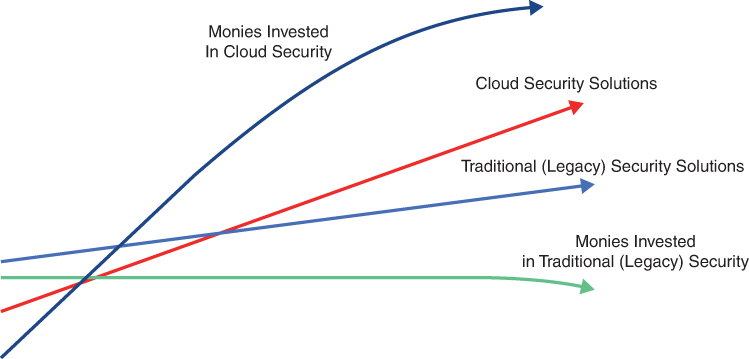

As you can see with Figure 1-5, the reason the security situation happened so quickly is easy to understand. Most R&D spending in the enterprise software space occurred and occurs in conjunction with a cloud platform, with private, hybrid, and public clouds as the target for that solution.

FIGURE 1-5 As vendors invested more dollars in cloud security solutions versus security solutions for traditional (legacy) systems, cloud security became much better on cloud-based systems and platforms than on traditional on-premises systems.

As you can see in the “Monies Invested in Cloud Security” line in Figure 1-5, most of the larger cloud players spent billions to develop services for this emerging market. The larger enterprise software players also spent significant amounts on cloud-targeted products and services. Most of these companies don’t break out their R&D expenditures, but it’s currently estimated that they spend 85–95 percent of their R&D budgets on cloud product/service innovations, on average.

As you can see on the “Monies Invested in Traditional (Legacy) Security” line, cloud innovations and development came at the expense of traditional security systems. Traditional systems with small or nonexistent innovation and development budgets are less desirable. Many enterprise software companies now treat legacy solutions as “sunset” products. They are unlikely to invest in these solutions in the longer term. The downside of this is that enterprises still pay high license fees for these products and do not receive the same number of updates and innovative improvements as products in the cloud.

This shift is occurring across the board, but specifically within security solutions. Today’s security in the cloud is often better than on-premises or legacy systems. This trend also extends to most major enterprise software systems, such as databases, development platforms, governance, operations, and any on-premises system that enterprises likely consider important to their operations.

In other words, the market shift is to the cloud. If you’re not willing to pay more for less, you’d be well advised to shift as well. This is an undesirable situation for many enterprises, with the market forcing their hand to move to cloud-based platforms. I call this “The Forced March to the Cloud,” which we’ll discuss in more detail in Chapter 9, “The Evolution of the Computing Market.”

Development Is Better in the Cloud

Current development trends are much the same as security. New cloud products provide the ability to quickly build systems to meet business requirements using innovative methods and services. Traditional development tools offer little innovation and many limitations. However, many of the traditional development approaches and mechanisms found new life in the cloud. In the last several years, public cloud providers upped their game, in terms of offering design, development, and deployment systems and services that are too compelling not to leverage. In the cloud these days, developers will have native access to advanced AI systems, big data analytics, auto scaling, and other cloud-based innovations. It’s an easy decision to choose cloud-based development platforms in terms of agility, speed, and innovation, and thus value.

The trend here is to focus on development systems in the cloud that do or provide the following:

Automated scaling. Developers and application architects no longer need to consider the problem of getting the software system to support higher workloads. This can be done for you automatically on most cloud-based applications. Because it’s usage-based pricing, you pay only for the additional resources you use. For many businesses, the cloud resources they leverage, and thus the cost, will align somewhat with revenue. That makes it self-funding as well.

Continuous testing, integration, deployment, and so on. Clouds can support emerging DevOps (development and operations) and DevSecOps (development, security, and operations) approaches and tool chains that exist entirely within the cloud. Clouds support development, but also the automation of the entire software development life cycle using an interactive and continuous improvement model.

This is a value discussion for later, so here I don’t get into a deeper discussion of DevOps/DevSecOps. However, simply put, the idea is that we can go from the design of an application to deployment using automated processes that deal with interactive testing such as performance testing, smoke testing, black box, or white box. Also, cloud DevOps provides the ability to automate the testing of application security, such as the ability to live up to predefined internal and external policies. Moreover, it can integrate and test the applications, including databases. Finally, cloud DevOps provides the ability to move to deployment, ensuring that the target platform is correctly leveraged and that we keep track of the configurations and application iterations that are released into production.

The ability to embed advanced services into applications that are native to the cloud, and thus to the development environment. Advanced services provide a huge amount of value to cloud-based applications with access to advanced AI systems, large database analytics, and specialized system development such as building and deploying IoT or edge computing systems.

Disaster recovery (DR) is easier on public cloud platforms, and typically cheaper as well. This is due to the fact that we can leverage other cloud platforms to do DR, and they have all of the benefits. This includes cost advantages and enterprises no longer having to maintain their own hardware just for DR operations.

Call to Action

This chapter is about how we got the initial value of cloud computing wrong and then figured it out along the way. The value drivers for cloud computing are different but more compelling than we originally thought. However, they are difficult to determine for most businesses, and thus many are still confused about how to determine the specific value of cloud computing for their business.

The call to action is to figure out what the value of cloud computing means for your business, your department, and even you personally. There are many ways to look at cloud values. It’s clear that there is no single way to build a value model that will work the same for all businesses. However, it’s helpful to conceptually understand the hard and soft values, and then use those concepts to come up with models that mirror the values that are most important to the business. That will result in a better understanding of the value that cloud computing can likely bring.

It’s important to mention that “no cloud” is always an option. However, as I mentioned in this chapter, we’re basically being forced to the cloud for many applications and data sets that might contraindicate a move to the cloud. You can’t always create a sound business case to move every existing workload. If adequate vendor support remains and there is not enough value involved in moving a workload or data set to the cloud, then it should not be moved.

The concept of value is perhaps the most challenging aspect of figuring out the most optimized path to any new technology. It’s easy to get overwhelmed as you make your way through the rapidly emerging maze of technology that includes cloud. Take it one bite at a time, and then make the right choices as to what should move to the cloud and what should not, with solid documentation as to why.