Chapter 11

Wrapping Things Up: Miscellaneous Insider Insights

Success consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.

— Winston Churchill

In this last chapter of the book, I wrap up what’s been said from an insider’s point of view and put a bow on how we need to think about the evolution of cloud computing…and computing in general. This book approaches the topics from the standpoint of what’s not being said in other books, articles, and podcasts to provide you with a unique perspective. There are no biases or conflicts of interest to color the truth, so you can make more informed decisions moving forward with cloud computing. If you’ve read each chapter in sequence or moved directly to this one, both types of readers will find good perspectives here.

I also understand that you, the reader, have many unique perspectives. Some of you work within the cloud computing industry as technology builders and providers, or as consultants and trusted advisers like me. Others are just starting their cloud computing journey and are hungry for the knowledge that will give you a leg up in your field, or to confirm someone else’s take on the current and future states of cloud computing. A few others are in traditional IT right now and want to shift their career to cloud computing. One book can’t be all things to all people, but I did write this chapter and this book with all these perspectives in mind.

Now let’s look at some overall benefits of cloud computing.

Cloud Can Make Life Better

The fundamental role of any technology, including cloud computing, is to make our lives better in some way. While our primary cloud focus is to return value to the business, the end game should always be to do specific human things such as serve the customer better, allow employees to be more productive, return equity to the investors, and return more to the humans than the amount of time and resources invested. If you keep those goals in mind, success will track directly to your technology project’s ability to meet those objectives.

“How will this proposal make most of the people involved happier than they are today?” That’s a question I often ask in meetings to discuss and decide any sort of technological shift or transformation: If the question meets with blank stares, chances are the work should not take place and the investment should not be made. Those who promote cloud computing, including myself at times, need to ensure there is a link back to the happiness of people. A project’s “before” and “after” happiness quotient often relates directly to business success.

Let’s break down this idea using an insider’s perspective. In other words, this perspective probably won’t match much of the hype and glad-handing out in the cultural zeitgeist of cloud computing. The goal here is to look at the true realities behind each benefit or issue described in this chapter. Let’s get going.

Cloud Supports Remote Work

A good result of the recent pandemic is the acceptance that work can occur anywhere, and employees should have the freedom to work where they want, even when they want, with some practical exceptions. For instance, airline pilots can’t fly via a Zoom call, and most manual labor doesn’t support remote work. However, most of the information processing workforce can now work from home, at the local Starbucks, or even at a remote cabin to change up the scenery. Anywhere that has access to a reliable high-speed Internet connection is a potential workforce location

As someone whose job can be done via the Internet from anywhere, I’ve been a remote workforce disciple for most of my career. Its advantages include employee retention, productivity, flexibility, and the often-underrated advantage of not having to spend hours in traffic each day. My round-trip commute took two to four hours daily throughout my 20s, 30s, and 40s. In that same amount of time, I could have written two books each year, spent more time with my family, and perhaps started a hobby. Instead, I was required to commute to an office where I would have very short interactions with other humans while there. If you add the time on planes and trains, that would have been well into 1,000 unproductive hours each year spent burning time and fuel.

Yes, we do need to meet with our coworkers outside of a Zoom call on occasion, and companies should promote a culture where there are structured human-to-human employee interactions. However, it’s an outdated concept to require all staff to report to an office each day, regardless of what they are working on or any true need to interact with others in person. Many businesses take an extreme view on the remote work issue and don’t allow it at all, including a surprising number of otherwise progressive enterprises.

Other businesses embrace remote work in its entirety and even allow creative options to foster business relationships that were once nurtured in an office environment. Examples include allowing travel to client sites to meet customers in person or coordinating employee attendance at a trade conference and then renting nearby meeting space so more diverse groups of employees could meet in person, such as an IT team and the stakeholder sales reps and sales managers who will use the team’s product. Even meeting quarterly with your team in a conference room could be more about the social aspect than it is about getting specific things accomplished.

Remember, companies that are still successful today had sales representatives located nationwide to call on customers within a geographical location rather than work from a centralized corporate office. Employee morale and human connections were of as much concern then as now. Good sales managers came up with solutions to those concerns, even in the days before Zoom and cell phones. Today 29 Google pages are returned on a search that addresses “How to successfully manage a remote workforce,” with links to dozens of books, blogs, and articles on the subject. The ground to break here is not as new as you think.

As a manager, you need a pragmatic understanding of what should be done to maximize productivity, retention, and thus profitability. So, the “it depends” answer comes back again. The ability to work remotely depends on what the job is and/or what the project requires. Take each remote work opportunity on a case-by-case basis. Almost every job involves hybrid work, which is a mix of remote with in-office work or vice versa, but the location should relate directly to the needs of the business and the employee, and not to some hard-and-fast rule that negatively affects employee productivity and retention.

Cloud computing also received praise during the recent pandemic for supporting a quick shift to a remote workforce. Cloud-based resources were already set up for access over the open Internet, including the ability to scale and the ability to support a reasonable level of security. You could consume those cloud resources anywhere over the open Internet. Enterprises that kept more traditional systems with limited remote access capabilities quickly installed more virtual private networks (VPNs), augmented security for remote workers, and even retrained staff that was mostly unprepared to work outside the corporate office building.

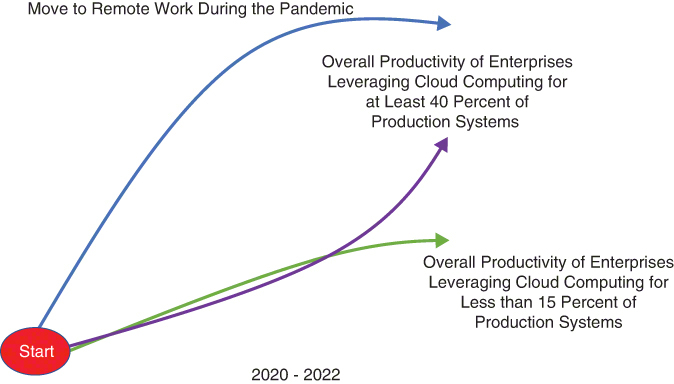

Enterprises that leveraged cloud computing prepandemic were often more technologically aggressive with more adaptable cultures and an existing remote workforce. They did much better at adapting to the “new normal” of work during and even after the pandemic (see Figure 11-1). Cultural adaptation is just as important as the adoption of cloud computing technology. Enterprises that were caught by their inability to adapt…well, many are now paying the price to dig out from their mistakes. “Adapt or die” has never been a truer idiom in this business climate.

FIGURE 11-1 We saw huge differences in productivity recovery between 2020 and 2022 among those who used cloud computing extensively during the pandemic and those who did not. Although many factors need to be considered, cloud computing made enterprises more agile overall with the ability to make quick shifts as needed, which proved especially important at the onset of workplace shutdowns in 2020. This time it was a pandemic, but the next work location disaster could as easily be manmade or another natural disaster.

Many enterprises that did cloud “wrong” lost productivity and thus market share, and still struggle to adapt as I’m writing this book. It’s a mistake they now regret. Big, strong companies won’t survive this latest technological revolution unless they maintain an adaptable and agile culture and technology stack. The insider advice? You’re either a disruptor, or you’ll be disrupted.

Support for Remote and Virtual Enterprises

The rise of the born-in-the-cloud enterprise is a result of cloud computing being around long enough that younger companies could take full advantage of cloud computing from the start. This typically includes organizations founded less than 20 years ago, with most between 5 and 15 years old. These organizations have almost all of their IT delivered as cloud services. You’ve likely heard about a few of these, including Netflix and Uber. Although not all have 100 percent cloud-based infrastructure, they lean more into public cloud computing than many traditional enterprises or more modern companies that act more traditionally than they should.

We found out during the pandemic that these born-in-the-cloud companies had a greater advantage for the reasons we covered earlier. Lockdown in place or not, it was easier to support a remote workforce if an enterprise did not have a traditional data center and thus did not need access to one. Companies often found that access to some data centers was either not allowed for the time being, or, in many instances, they could not find employees who were willing to venture out to fix stuff in their data center. I’ve heard story after story of CIOs struggling to find the ways and means to fix simple problems, such as the power supply for a router or a storage server that was failing, things that would take less than a few hours to fix and usually cost almost nothing to repair. They ended up stopping all IT processing for hours until the CIOs could find creative ways to remotely fix these issues. A huge number of enterprises learned painful lessons during that time. Thus, today’s more aggressive moves to cloud-based platforms hardly come as a surprise.

This climate gave rise to complex virtual companies that don’t own or rent real estate or offices, at least not permanent ones. Most importantly, they own few if any servers, and they typically lease data center space. Company-issued laptops, smartphones, and/or tablets are the only potentially owned hardware, although it’s often leased, or remote workstations are employee-owned. Most of what a virtual company “is” exists as a concept versus a brick-and-mortar company that’s measured by its physical assets. Virtual companies feature a loosely coupled group of people who work together using technology to achieve whatever goals the company needs to achieve, such as building a cloud service, building a physical product (outsourcing manufacturing), selling products, or selling services. For the most part, unless you specifically investigate a virtual company, you would never guess it’s completely virtual.

The insider perspective here is that cloud computing makes virtual companies possible. Cloud proves that all IT services including sales, order management, accounting, inventory control, collaboration, DevOps, and most other core business and technology services can be delivered as services to any person or system in the company that needs access. While completely virtual companies are still few and far between, the lessons learned from the pandemic are leading many new companies to sell their office real estate and/or cancel office leases, and only rent data center space.

Existing and more traditional companies now see a hardware path to a virtual state, but it’s difficult if not impossible for these types of companies to give up all physical buildings and physical data centers that depend on what they sell. The core issue here is culture. For a company that maintained an office for the last 100 years, and for employees who joined the company to work in an office, it’s much tougher to reduce or eliminate the traditional office. The same can be said for owned computer hardware and even owned data center space. As we said earlier, legacy systems are hard to dispatch. However, there are creative alternatives to maintaining your own data centers such as co-location providers that rent out data center space much like real estate, or managed services providers that own and maintain the hardware for you and may even manage your public cloud services, if needed.

This area becomes another one where companies need cloud computing if they want to be completely virtual and enable all employees to work remotely. What limits this movement for many companies is culture and a lack of willingness to make drastic changes. News flash, the market may make those changes for you.

Support for World Changes and Evolutions

The feature I point to as the core value driver of cloud computing is agility. Traditional IT approaches and components cannot expand or change as quickly around new and emerging opportunities. Cloud-based systems can deal with most agility issues. Success with agility comes down to understanding those capabilities and how to leverage the right solution to solve the right problems. We’ve covered agility already systemically throughout this book, at least conceptually, but it’s helpful to point out specific areas where the benefits are better realized.

Support for Sustainability

We have an entire chapter on sustainability (Chapter 8), so I won’t restate those concepts here. However, it’s important to support sustainability, and that means you must understand how to support it. Many companies with good cloud sustainability intentions make things worse when they leverage cloud computing. Some get confused because private cloud has the word cloud in it. For instance, many don’t realize a private cloud’s carbon impact is much greater because you still own and run your hardware in an existing data center.

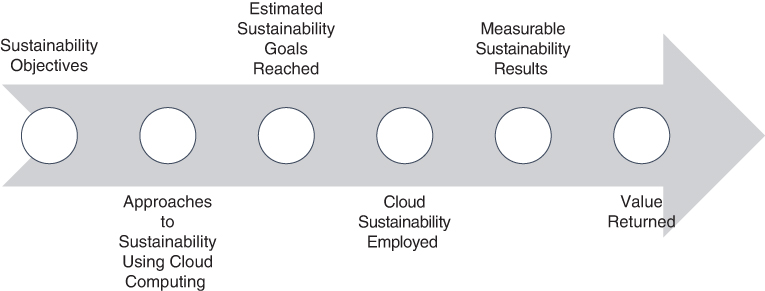

The real sustainability value we get from cloud computing is more difficult to define than most enterprises understand. Just using “a cloud” does not guarantee a return on sustainable value, and it’s easy to make things worse if you’re not careful. Figure 11-2 depicts what this process should look like to evaluate the use of sustainable technologies such as the cloud. The goal is to save carbon and return value to the business. A positive sustainability audit could mean access to more business and/or compliance with regulations. It could even save energy, which saves the company money. Of course, being a good citizen of the world is the overall motivation for reducing carbon output.

FIGURE 11-2 Sustainable cloud computing is not as easy to achieve as most people believe. You must create a process to clearly define the objectives, approaches, and goals, and then determine how you will approach sustainability using cloud computing. Then you need to measure the results and figure out how much value is returned.

Democratization of Computing

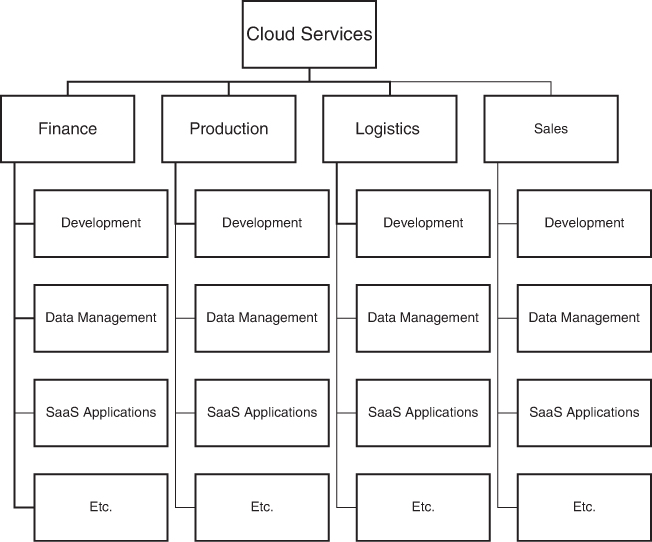

The democratization of computing is nothing new. COBOL, a programing language developed in the 1970s, theoretically allowed executives to write programs themselves. Spoiler alert, few executives in the 1970s had mastered the use of automatic teller machines, so even fewer volunteered to write software programs. However, the idea stuck and evolved. Today we no longer need to translate requirements from the end users to build our vision of their vision of business-critical systems. Now that most users are familiar with the use of apps on laptops, pads, and phones, they have greater potential than the execs of 50 years ago to use an app or dashboard to build what they need themselves. The advantage is speed, cost of development, and empowerment to get the end users to take ownership of their solutions (see Figure 11-3). Win-win.

FIGURE 11-3 Democratization of computing by using cloud computing means that IT functions can be spread among the departments in an enterprise. This allows each department or team the power to build and deploy applications, manage data, leverage purpose-built SaaS applications, and so on. They are empowered to employ the exact technology they need. Be aware that there are many trade-offs with this approach.

Of course, democratization does not work all the time for all people. It’s people rather than technology problems that usually eliminate a democratization approach. It’s understandable. Most people are hired to do a non-IT job; then we push a programming tool in their faces and ask them to become software engineers, as well as do their core job. Remember, most people still think “the cloud” is where they store their pictures, music, and files from their phone and/or laptop. Think about the likely response if you ask those same people to write a custom business app or program. In my view, the technical aptitude of users will continue to evolve, but democratization for current non-IT workers will have limited success until they become sufficiently incentivized to become part of the process, or after they see a few peer successes with projects.

In that same vein of aptitude evolution, several new cloud-based innovations provide an easier entry into development for laypeople. A recent rise in the popularity of low-code and no-code development resulted in application development tools that are purpose-built to allow anyone with a bit of training to build, deploy, and operate applications. These tools use mostly visual interfaces that allow most semi-technical people to “drag and drop” their way to application development. Some of these tools also allow code to be added behind the application components to define custom behavior. Other low-no-code tools either don’t require coding, or they provide visual methods to create code-like mechanisms. They also provide database access, and some tools provide access to any number of APIs that exist outside of the tool.

The downsides are what you would think. Because most of these low-no-code tools are cloud-based, they are limited in what they can do. Although they can build applications that are 100 percent defined by a trained end user, they are not optimized applications. They leverage only one technology stack that is typically unoptimized for that application’s performance and thus can be costly to run on public cloud systems that charge for the extra CPU cycles used and extra data stores. That’s why I have reservations about the widespread use of low-no-code technology, especially on the heels of preaching the need to optimize cloud solutions for technical and cost efficiency.

But don’t let that dissuade you from leveraging the democratization of cloud computing systems for business purposes. It’s fine to do things like create a prototype or build quick systems that will be improved later. However, for fully optimized applications, you still need to leverage more robust tools (we can call these “high-code” tools). So, I’m not buying that low-no-code development will replace more traditional approaches to cloud-based development. However, like any solution, there are some problems that low-no-code tools will solve best.

Punching Above Your Weight

A great thing about cloud computing is that it allows once insignificant and undercapitalized businesses to punch above their weight, which also relates to democratization—this time as computing power. Almost any business can leverage advanced computing systems that were once too costly for the “little guys” to leverage. They could not afford hardware and software that cost millions, so they had to make do with suboptimal solutions. That gave most big competitors a huge advantage over new and/or smaller competitors in their markets, and the big guys often pushed the little guys out of the race altogether.

Those race days ended with the evolution of cloud computing over the last 20 years, especially with the rise of SaaS in the early 2000s that allowed ERP and CRM systems to be leveraged as-a-service. This evolved into the rise of IaaS clouds which allowed businesses to leverage expensive storage and compute systems without a single investment needed in data centers or the hardware that lives in data centers. I saw this play out firsthand in my tenure as CTO and CEO of various startups over the years. I had to raise at least $1 million of funding just to get the bare minimum infrastructure in place needed to develop and market the resulting technology products. Of course, that was just for entry-level startup activities. There were also upgrade and expansion cycles that drained most of my startup cash. At the time, there was no working around that startup scenario.

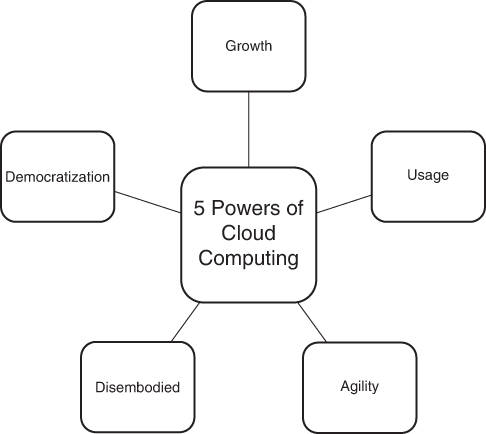

Today, the five powers of cloud computing make a true difference in how we do business now versus how we did business just a short time ago (see Figure 11-4). These powers break down as follows:

Growth is the ability to scale cloud computing technology up and down as needed, now and into the future. There are few or no restrictions as to how fast you can grow, albeit you’ll pay for all that you leverage.

Usage is usage-based cost, in that you’ll pay only for what you leverage. As you scale the business and your revenue grows, you’ll use more compute and storage resources, and pay more for using a greater amount of those services. This lines up with how we want to run our businesses, where costs track with usage, which tracks with revenue.

Agility is the ability to change when you need to change and do so at the speed of need. It doesn’t matter if you’re moving from a relational database to an object-based database for better analytics support or moving applications to serverless computing. With cloud computing, you can adjust as needed to respond faster to market changes or move fast when you need to quickly push a new product into the market based on a rising opportunity. Look at companies that pivoted during the pandemic from manufacturing dresses or safety helmets to making masks and face shields as demand for those products far outpaced supply during the pandemic. Or the designer clothing manufacturers that sped new designer masks to market to meet exploding demand.

Disembodied means we can use cloud-based resources at any time, for any reason, from anywhere. There is no physical requirement that people or systems be at a specific location, as we covered earlier in this chapter. Entire companies that use cloud computing can be 100 percent virtual, which means they can adjust quickly and burn less cash because they don’t have to rent office or data center space. Talent should also be easier to find since the virtual business can employ anyone from anywhere.

Democratization empowers employees, departments, and other areas of the business to directly participate in system development, deployment, and operations.

FIGURE 11-4 Cloud computing allows small- and medium-sized businesses to punch above their weight. They can leverage cloud computing as a force multiplier to build a business faster and disrupt more traditional businesses. These powers make cloud computing the great equalizer.

Changes in the Skills Mix

Back to people. Cloud and IT job descriptions and qualifications are undergoing major changes as we identify the mix of skills required to drive cloud computing within enterprises. Some of these changes won’t come as a surprise, some of you will disagree with me, and others will be a tad confused. Let’s walk through it.

The trouble with any substantial change in the skills mix needed to drive any new technology is the latency between demand for the skills and the labor market’s ability to respond and adjust. This happens so often in the evolution of technology that I find it surprising when the supply and demand for new skills seem to take so many people by surprise. Indeed, during the pandemic, most believed there would be a huge downturn and all technologies, including cloud computing, would be negatively impacted. The opposite occurred. Enterprises and consulting firms scrambled for talent to build cloud systems to support the new remote workforce demands. What more of us realize now is that technology and spending do not limit progress; it’s limited by the number of skills you can quickly recruit into your organization to implement that technology.

It’s a huge value if you can see how those virtual skills will change moving forward because you can proactively train and recruit to make sure those skills are at your fingertips when you need them. Ironically, hiring and/or training ahead of demand is something most enterprises don’t like to do, seeing the risk if the demand never materializes and the new hires or newly trained staff won’t provide their anticipated value to the company, at least not right away.

However, if you create a true vision of your company or government organization, you’ll understand what technologies you’ll be using now, two years from now, five years from now, and so forth. It’s just a matter of doing skills planning that will determine if it’s best to recruit new hires, train existing personnel, or use outside contractors to fill the roles you’ll need.

If you must respond at the last minute, any value that cloud computing or other technologies could bring goes right out the window as you compete with dozens of other companies for each somewhat qualified candidate. While you wait for the right people to show up, your enterprise will die the death of a thousand cuts. It’s more likely that you’ll hire the wrong people, or projects will be delayed while you wait for skills to show up that get more difficult to find as time progresses. So, understanding when and where the skills will likely change is not only a good idea but also a survival skill.

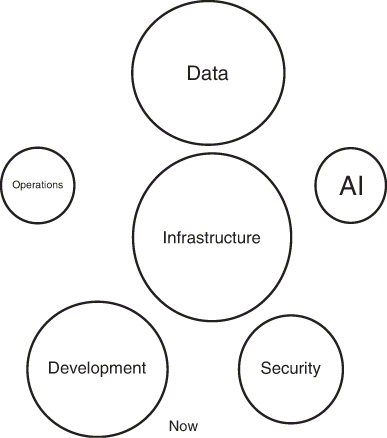

Figure 11-5 depicts where we were at the time this book was published. This is an amalgamation of all cloud skills that exist within enterprises, covering the major technology patterns that enterprises use in their current deployments. There are a few things to note. Cloud operations are important because most enterprises are not focused on obtaining cloud operations-specific skills. Instead, they assign operational duties to people in other technology categories such as data and AI. In many instances, cloud operations skills are not being formally addressed as a specific skill set and discipline. You need a separate team that focuses exclusively on holistic cloud operations.

FIGURE 11-5 The cloud computing skills mix today is even between data storage, infrastructure (computing, networking, and so on), security, and development while AI and operations skills lag. Figures 11-5 and 11-6 show how needed skills will shrink or grow, relative to the larger cloud computing space. They’re designed to depict what changes will be made in the number of people you’ll need for each category of cloud technology, relative to the entire skills market space. Although this is just an educated guess, it encourages a discussion about what skills will be needed in the future and the necessary planning.

Figure 11-6 shows my insider estimate about how skill needs will break out in the years to come, say, in the next 5 to 10 years. There will be a huge increase in demand for cloud operations skills that will include AIOps, observability, FinOps, and so on. We spent a lot of time and money building and migrating systems over the last 10 years. We’ll put in a similar effort to keep these things running smoothly. This effort will partly focus on employing cloud operations across enterprises because it makes more sense to consolidate operations skills within a cloud operations team. A CloudOps team can do this job more efficiently because we combine many similar or related operations tasks within the same team and the same technology stacks. We also need to understand that the CloudOps team must deal with increasing overlap in operations such as performance, backup, recovery, and reliability, all being types of services that need to span all aspects of cloud computing, including all circles (see Figures 11-5 and 11-6).

FIGURE 11-6 Moving forward, we’ll need many more people with operations skills. AI engineers will be in even higher demand. Security will grow a bit, but not as much as many would predict. Development automation will reduce the need for development and deployment skills, as infrastructure automation will reduce the need for infrastructure skills.

Other changes in skills mixes are easier to predict, such as the rise of AI, considering how important it will be to businesses moving forward. The rise in security is now growing as fast as most predicted. We’ll soon deliver much better security with fewer people as advanced security tooling automates manual tasks and provides better coverage to AI systems, observability, and automation; thus, the demand for people with cloud security skills will remain relatively flat.

The need for cloud data skills will shrink for the same reasons. Automation, abstraction, and federated data will require fewer people relative to the growth of the cloud computing space. Their data skills will likely shift to focus more on data usage and data value than traditional database admin tasks such as changing structures, adding features to databases, and overseeing the use of data within applications. Again, development work shrinks relative to the growth of the space. It’s not that we’ll build fewer cloud applications, but the tools will become more efficient and optimized so that it will take fewer people to crank out the same number of applications. Also, the adoption of low-code and no-code solutions will democratize some of the development. However, as I’ve previously asserted, not as much as the market now believes.

The idea here is simple, but the execution is tough. We’re making some educated calls about what skills we’ll need in the short and long term for the business. It takes as much as a year to hire a good cloud operations engineer or a good cloud AI specialist. Creation of a plan for the skills to hire and what and how to train new hires can affect your ability to succeed with cloud computing more than any other factor. Who would have thought that cloud success would revolve around people issues rather than technology issues? (Well, I did predict this too.) People are becoming the most important resource for cloud computing. Funny how people are such important assets these days when many once believed that all human value could be completely automated. That’s not the case now, and I doubt it will ever be the case.

The Objectives Change

Cloud computing value as defined in the past has been a bit of a moving target. You may recall from the earlier chapters that cloud value was once based on operational savings created by avoiding capital expenditures. Now it’s more about business agility and the ability to scale. This shouldn’t be news to anyone who’s read along this far into this book, but it’s thinking that most enterprises still don’t share. So, the next lead story should be: Enterprises finally accept that cloud computing is not just a movement to cheaper servers; it’s a fundamental foundation to improve and modernize the business.

My question to new clients is often, “What do you consider the core value of cloud computing?” If the answer is “cost savings,” there needs to be another discussion before we get started because they are missing the true value of cloud computing. Based on each company’s unique situation and criteria, I sometimes advise them not to move to public cloud servers because staying put will likely be the cheaper path, at least for the time being. It’s always interesting to see the looks on their faces when I give that answer.

There are a few hard realities about moving to the cloud that we all need to understand. For most, you have little choice. Consider the cloud innovation dollars that enterprises have spent for the last five to seven years. They can’t stay off public clouds because they’re already on them, and they won’t gain an advantage from the technology providers’ investments in innovations. Another confusing spin on this fact is that not all applications and data should reside on public cloud providers. Moving forward, you need to wisely pick the applications and data sets that move to the cloud. Look at the true value of cloud computing as it relates to these applications, meaning business advantages such as agility and scalability, with the pragmatic review of an application and data in terms of where they should be hosted to bring the most value back to the business.

Confused yet? Long story short, we now have options for where applications and data should exist to bring the most value back to the business. All things and all places need to be considered. How we view cloud and non-cloud resources is changing and will always change. While we have cost/benefit data points to consider, at the end of the day we must take the criteria and metrics and then determine the right location for applications and data. The criteria should include values to the business, such as operational cost savings, agility, speed, and scalability. The analysis should point to and cost justify one of three possibilities: Leave it be, lift-and-shift, or refactor.

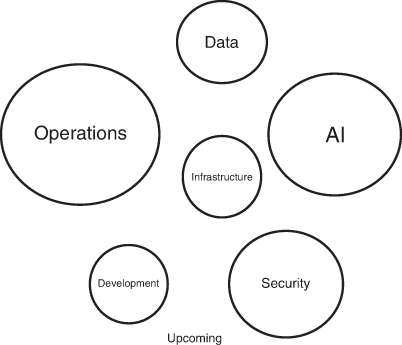

As you can see in Figure 11-7, what I assert here is that business agility and growth become stronger drivers because, right now, most enterprises don’t even consider them as value factors. At the same time, the “migrate, build, and deploy” approach to move to the cloud as fast as possible will fade as the primary driver to migrate to the cloud. Although many understood this years ago (including yours truly), agility and growth (agility) are just now catching on as the primary drivers and objectives for moving to public cloud providers. It’s about time.

FIGURE 11-7 The current drivers to quickly migrate to the cloud and create net-new cloud applications will be slowly replaced by business agility and growth drivers. The focus will turn to optimization and how people find cloud technology useful. In other words, it will become more of a business-oriented objective versus a technology-oriented objective.

The Market Absorbs the Weak, and the Weak Emerge Again

The public cloud market was very crowded around 2009 when every enterprise technology company, managed services provider, co-location provider, and a bunch of telecom companies and underfunded startups had a public cloud of some sort. The functionality of their versions of a public cloud was all over the place, with some even setting up physical servers when their cloud computing customers requested them. So, you would request a resource, such as a storage and/or compute server as you do today from a “public cloud dashboard.” It would take several hours for the resource to come online while a physical server was installed in a rack on your behalf, meaning that it would be removed from the box by a human, configured, tested, and physically put online. Although that’s a funny story I sometimes tell when keynoting cloud computing conferences, it’s a scheme that worked well, all things considered.

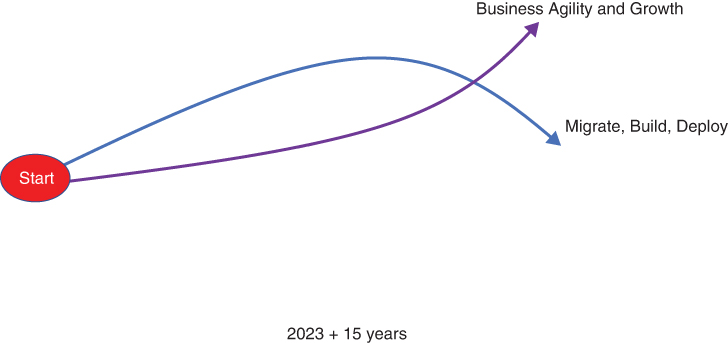

We know now that cloud providers quickly normalized as the market understood the huge amounts of investments required for a cloud provider to exist. This happened from about 2010 to 2016, as depicted on the left side of Figure 11-8. This is a pattern we’ve seen repeat itself in the technology space when the market absorbs weaker players that don’t have enough cash to compete in a resource-intensive technology space such as public cloud computing. The smaller players are purchased by the bigger players and the market consolidates. In the case of public clouds, the market consolidated around three primary players with a few secondary players.

FIGURE 11-8 At the start of cloud computing, the number of public cloud providers numbered in the dozens, with most telecom companies promoting a public cloud. Then the market normalized when providers realized the large investment required to succeed. There will be more public cloud providers again that focus on industry cloud services and other niches moving forward. Because most enterprises already leverage multicloud, adding smaller cloud providers will become easier as we continue to solve multicloud complexity problems.

As the cloud computing market matures, we’ll again see a familiar pattern emerge. Smaller players are beginning to enter the public cloud marketplace with a specialty focus on niches that the larger providers do not yet address. As the number of public clouds grows, the cloud market will again mature (see Figure 11-8).

Secondary niche IaaS public cloud providers are nothing new, by the way, with offerings such as file sharing, backup, and recovery services. These secondary public clouds provide a niche service designed to compete directly with the larger public cloud providers. What’s most interesting is that they are becoming public clouds unto themselves, purpose-built to compete with more traditional cloud providers. Thus, this is an existing pattern of evolution that’s been underway for the last 10+ years; I’m just calling out the growth that is about to occur.

The niche market is a bit different from cloud computing ecosystem technology (a technology designed to add value to a cloud computing provider’s product). For example, if you go to the “marketplaces” for any larger public cloud provider, you’ll see hundreds or thousands of providers that offer everything from security to automated spelling correction that works with a specific public cloud provider. The difference between an ecosystem and a niche product? When leveraging an ecosystem product, you’ll typically do so by working through a public cloud provider such as accessing a particular enterprise’s database. The new IaaS niche public clouds provide direct access to their cloud without going through another cloud provider. They are legit public clouds that I call “baby clouds.”

A rising number of smaller public clouds may replace specific niche and standard cloud services markets that the public cloud providers now dominate. These public clouds may have services that compete directly with public cloud providers, but they have specialized public cloud services that are not offered by traditional public cloud providers. Most of these will be industry-specific services, such as databases that are purpose-built for retail, health care, or finance, or even specific supercomputing and quantum computing services that the larger public clouds may also provide.

Typically, the reason an enterprise would go with one of these emerging “baby clouds” is that they offer a full package of cloud products and services that existing public cloud providers don’t offer, such as data and APIs that are purpose-built for trauma centers. Eventually, larger public cloud providers will also enter industry-specific cloud markets. For now, baby clouds will continue to pop up like mushrooms, and one or more may someday evolve into a behemoth capable of head-to-head competition with today’s Big Three public cloud providers. However, history indicates that an emerging contender will be purchased and absorbed into one of its larger competitors.

This coming evolution makes the public cloud computing space more interesting for a few good reasons:

First, the widespread use of multicloud makes it much easier to include other nonstandard public cloud providers and place them under the same operational and security frameworks as we do other public cloud providers, as you may recall from the multicloud chapter. This opens the number of options that cloud solutions architects now have by not limiting their choices to the “walled garden” of a single public cloud provider. This also assumes that enterprises will first optimize their cloud systems to bring multicloud complexity under control.

Second, and most interesting, baby clouds provide a third choice when it comes to public cloud providers and traditional data center systems. They are still a public cloud and should come with the convenience and scalability of “traditional” public cloud services. Baby clouds may also provide analog resources at greatly reduced prices. For instance, you may pay .002 cents a gigabyte for object storage on a larger public cloud provider while a smaller public cloud upstart offers the same service at .0001 cents a gigabyte. If all things are equal (and they never are), then that would be a good fiscal choice if no other integrated features are needed that are only offered by a larger public cloud provider. In most cases, I suspect a cheaper analog service will not attract the largest share of baby cloud clients. The lure will be a niche service that the larger public cloud providers may not provide such as risk analytics to support financial trading, or the ability to calculate the best investment path for a portfolio. Those are deep specialty niche services that can’t be easily replicated.

Third, the additional competition will promote more entrants into the public cloud space but also provide pressure on public cloud providers’ prices. The larger public cloud providers with their many billions of dollars in resources have built clouds that are pretty much the same. The prices and terms are a bit different, but they have more in common than not in common. That situation levels the cost of using a large public cloud from provider to provider. They have R&D and production expenses that are built into their pricing models, and those costs are higher than the smaller more efficient players. The existence of more baby cloud providers that can be easily incorporated into a multicloud will put pressure on existing cloud pricing. At the very least, it removes worries about cloud lock-in.

Of course, there are and will be downsides to leveraging baby clouds. They typically don’t have the same number of points of presence as larger cloud providers. However, some of the smaller public cloud providers may leverage the larger cloud providers to support their infrastructure, including points of presence. This is done today. A baby cloud may use a public cloud provider to manage access and storage on the back end for services such as personal file storage. You never even know that they are leveraging an IaaS public cloud provider, even though that is where your data exists.

We’ll see cases where baby cloud providers don’t own physical servers but instead leverage a larger public cloud provider to host their specific cloud services. This may fall out of favor if baby clouds become true threats to the public cloud provider’s business and the provider abruptly kicks the baby cloud off their cloud. Also, baby clouds could not offer a profitable discount to another public cloud provider’s analog resources. So, I see many baby clouds moving to physical systems they own, much like we saw over the last five years when some gaming services moved from public clouds to owned systems to have more control and save money.

The insider takeaway? Watch for the growth of choice. Enterprises are much more likely to add all the larger cloud providers to their multicloud cloud services portfolio, but many of the baby clouds will present a more difficult decision as enterprises struggle to tame the complexity monster. Eventually, I suspect the market will instigate the evolution and integration of baby clouds into more multicloud portfolios. It will be a step in the right direction.

Cloud Technology Continues to Be a Value Multiplier

As depicted in Figure 11-9, the cloud remains the single most effective technology that enterprises can leverage to take their value to the next level. Cloud computing allows enterprises to punch far above their weight in the marketplace. In terms of cash spent relative to value delivered and acceleration to value, the ability to find and capitalize on innovation remains the single most compelling reason to leverage cloud computing today and into the future.

FIGURE 11-9 The cloud will continue to be a not-so-secret weapon to increase corporate value, either through innovation or better productivity. While many businesses missed the first wave of cloud computing, I predict we’ll see a surge in digital transformation and IT modernization using cloud computing as a force multiplier to expand value.

Not all enterprises will leverage cloud effectively. Most won’t. Missing will be the skills and vision required to configure the use of cloud computing as a net benefit to the business. There are lots of ways to succeed with cloud computing and lots of ways to fail. Many who promoted cloud computing in their enterprises assumed that success was a foregone conclusion just by using cloud computing. Most cloud providers also promoted that point of view to accelerate adoption when cloud computing was new.

Now we know that cloud computing is another enabling technology that enterprises can use and misuse. The inside advice I hope you take away from this book is that cloud computing is not magic, and its adoption does not ensure success. Enterprises need to make a series of strategically sound decisions for cloud computing to deliver its promised value. For many enterprises, cloud computing will be another path of trial and error, certainly for most of those who did not read this book.

Call to Action

In writing this insider-focused book, I tried to provide information that you won’t find in other places. These days I’m a bit concerned that many information resources are not as candid and pragmatic as they once were. This is an evolution of the media in general to address the fact that most of today’s readers have short attention spans. Many technical articles now feature short sound bites of advice rather than in-depth and concise information about the topic of the article. A problem or evidence that a problem exists is often the topic of an article, with no guidance or advice about how to solve the problem. Even books are written in such a manner these days, which is bothersome. For example, your car has a flat tire. Here are the bad things that will happen if you drive on that flat tire. Change the words flat tire to cloud complexity, and you will see the theme emerge in many technical publications.

The key here is to question everything as you move forward with cloud computing or any other technology. Don’t assume a security approach and technology are right for you just because an analyst or another company’s CTO used them successfully for a different project. Every project is unique. Also, be aware that analysts often have as many technology providers as paying clients. I would consider their advice with a grain of salt, despite any statements of unbiased advice.

The tech press suffers from the same issue. However, it’s just the maturation of the market. (1) The press and analysts need to find sources of revenue. (2) Technology providers have marketing dollars to spend. (3) Problem, meet solution. To be honest, some of the publications I’ve contributed to have these kinds of sponsorship issues, meaning we’re asked to opine on specific technologies that are provided by companies that support the publication through advertising or Webinar hosting. Or, look at the vast number of surveys about technology subjects. You’ll rarely or never see a survey sponsored by a technology provider that returns information that’s not in the sponsor’s favor.

Some technical publishers and their publications are hyper-ethical, and they will even turn down lucrative advertising that could imply a conflict of interest. Other publishers and publications act as mouthpieces of technology companies. Learn to recognize the difference.

You may still gain valuable information about the reasons for the existence of a problem from a mouthpiece article, but the solution will be focused on the product that sponsors the article. Search for articles sponsored by competitors of that product to get a more well-rounded point of view about potential solutions.

Different points of view lead to more correct solution choices, which lead to greater success. That’s why it’s important to continue supporting the tech press and tech analysts. Gather data points wherever they exist, from normal channels that include the tech press, analysts, and product providers themselves, and from those who have an insider track on this technology, people like myself and a handful of others.

Whenever I undertake a technology project, I consider potential conflicts of interest with data points that may prove helpful. Two things can be true. Information can be useful and correct but also purposely slanted toward a particular conclusion. Be savvy about where you get your information and the motivations of the people providing it.

Today, many IT decision-makers have only a fraction of the information they need to make informed decisions about cloud computing. These decisions will eventually prove pivotal to an enterprise’s success or failure. This book’s purpose is to even the playing field and spread cloud knowledge that can lead to cloud success. Perhaps you learned more about a few new cloud computing concepts and facts. At the very least, I hope the information in this book will encourage you to ask more informed questions about how all this cloud stuff works together.

Remember, you can’t get answers if you don’t know the questions.