The first step in becoming a successful negotiator over the long run is to understand precisely what negotiation is—and what it is not. Let's start with a definition of what it is:

Negotiation is communication between two or more willing parties with conflicting goals in order to achieve mutual gain.

That eighteen-word sentence contains a lot of powerful ideas, so let's break it down phrase by phrase.

Negotiation is communication—It's a forum for exchanging thoughts, messages, and information. It's not a sport or a battle or a magic act. It doesn't require any special tricks or even oratorical genius. It is simply an attempt at connection.

...between two or more—The key word here is "more." Even when only two people are in the room, on the phone, or exchanging e-mails, there are usually more than two parties involved in the negotiation at some level. These invisible participants might include the boss who has to approve the deal, business partners who have to accept it, or family members who are able to influence the outcome—which is why force, by and large, is an ineffective negotiating technique. You might be able to force a timid negotiator to accede to unreasonably one-sided terms, but when that negotiator takes that deal back to the influencers for feedback or to decision makers for approval, it stands a high chance of getting tossed out. Therefore, it's vital always to give the other party not just a fair deal but good reasons the party can take back to demonstrate why it's a fair deal.

...willing parties—Unlike intimidation, unsolicited sales pit ches, or courtroom trials, negotiation requires the voluntary participation of all parties. Everyone enters the process through his or her own free will. If someone is unwilling to negotiate, whether because of mistrust, long-standing enmity, or mere lack of interest, that person cannot be forced. What is more, everyone has the right to walk away at any time in the negotiation if he or she is dissatisfied with the process or the terms being offered. Without all parties being on board, there can be no resolution.

...with conflicting goals—Here's the rub. The reason so many people say they dislike or even fear negotiation is because it entails facing up to conflict. If there is no open conflict—for example, we both want to go out for Chinese food tonight (or you secretly don't want to, but say you do)—we simply have a conversation. Only when one of us directly raises a point of conflict—I want Chinese food and you want Italian—does a conversation become a negotiation. However, it is imperative to keep in mind that negotiation doesn't create the conflict. The disagreement already exists. Indeed, if such disagreements are never addressed, they can build up a store of resentment that can destroy relationships. Negotiation, done properly, is the tool that enables us to resolve the conflict and put the relationship back on course so that it can move forward profitably, productively, and happily.

...to achieve mutual gain—This is what separates negotiation from simple persuasion. Although persuasion is an intrinsic part of negotiation, negotiation isn't just talking another party into giving you what you want. Rather, all parties must acknowledge that everyone at the table has the right to gain something. I am not talking about an equal division. Who gets what will be determined by many factors, from power to competition to market conditions to the value each party brings to the deal. But there must be an understanding that everyone has to win something.

Even police hostage negotiators are willing to let the robbers holed up inside of a bank have something, although it will be far less than they demand. New York Police Department's chief hostage negotiator, Dominick Misino, explained in an interview in Harvard Business Review, "Before the bad guy demands anything, I always ask him if he needs something. Obviously I'm not going to get him a car. I'm not going to let him go. But it makes excellent sense to be sensitive to the other guy's needs. When you give somebody a little something, he feels obligated to give you something back. That's just good common sense."[22]

For me, it is this quest for mutual gain that makes negotiation exciting and rewarding, despite the occasional discomfort along the way. All the parties at the table have entered into the process in the belief that if the right terms could be worked out, they would be better off working together than not. We need to keep this in mind during the heat of the negotiation, when we naturally tend to focus on areas of disagreement and forget that all parties have actively chosen to invest time in talking to one another in the hopes that they will benefit by settling their differences.

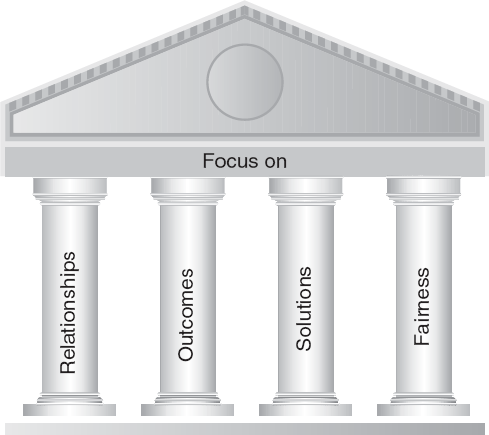

Relationship-based negotiation differs from the standard definition of negotiation in that it sets a more ambitious target. Instead of aiming solely for mutual gain in the terms of a deal, it aspires as well to develop the mutual trust, reliability, and future cooperation that will create value stretching far beyond the deal. Such a strong and enduring edifice is constructed on four central pillars: a focus on relationships, outcomes, solutions, and fairness, as shown in Figure 4.1.

The aim of every negotiation is to find a way to collaborate with others so as to benefit yourself now, throughout the life of the agreement, and possibly into the next agreement, even when the situation changes or problems arise. To create effective collaboration you must start by inspiring cooperation. As we saw in the preceding chapters, cooperation is far more dependable and easier to achieve when others like you, trust you, and feel that you have their interests at heart (and not just your own). In the end, they must feel that they too are benefiting from collaborating with you.

While negotiation will always involve an element of conflict, it rarely furthers your goals to turn that conflict into personal animosity. Berating, accusing, snubbing, or generally insulting others is not likely to win them to your point of view. Behaving secretively or mistrustfully merely makes them more secretive and mistrustful. Even when your differences in outlook are extreme (such as between the police hostage negotiator and the bank robbers), you gain nothing by vilifying or preaching at your negotiation counterparts.

In most of the world outside of northern Europe, North America, and Australia, a respectful and comfortable personal relationship has to precede any serious business negotiation. This may feel terribly time-consuming if you come from one of the more individualistic societies, but it is necessary, period. If you try to force the process to get straight into dealmaking, you will most likely end up with nothing. Even in the rare instance that you do get an agreement, it will not be reliable.

Wherever you negotiate, you will benefit by first trying to understand the other party's concerns and build empathy, then working together from that positive foundation to resolve the issues dividing you. Otherwise you will just butt heads. Let me share a story that was certainly a valuable life lesson for me in not letting different perspectives turn into attacks on people.

When my son, Matt, turned twelve years old, he quite naturally began to grow much more independent and argumentative. The sweet, pliant little boy was replaced by a budding teenager whose personal motto was "every rule is made to be resisted." While I understood intellectually that this was a normal stage kids go through, in my self-centered core I felt that Matt was being obstinate for the sheer joy of torturing me.

One frequent argument was about what time he was supposed to go to bed. Because he had to catch a school bus at 7:00 each morning, his designated bedtime was 10:00 p.m. Yet more and more often this bedtime rule was becoming a struggle, with Matt pressing to stay up later to watch some TV program or pretending not to hear when his father or I reminded him of the time.

One night my husband was out of town and I had been working late with a client. I came home tired and short-tempered. My son and I had a late dinner, and at 10:00 I told him it was time for bed. After the usual protests and arguments, he reluctantly headed off. Around 11:00, however, as I walked past his room on my way to bed, I saw that his light was still on. I admit it: I snapped. I banged open his door and attacked: "Why do you always defy me? Why can't you follow rules? Why do you have to make everything so difficult?" I shouted.

Somehow in the middle of this harangue a small, rational voice in my head spoke up: "Melanie, you just spent all day with a client telling them to attack problems, not people. What are you doing now?" In that moment I saw myself as my son must have seen me—and it wasn't pretty. I saw the fear and resentment in his face, and I knew that my behavior had created those feelings. I saw that my scolding words were creating, not reducing, his defiance. To my shame I realized that I had become so upset over a point of disagreement that I had lost sight of my greater goals. Yes, I wanted him to get enough sleep, but I also very much wanted to have a warm and communicative relationship. Moreover, I wanted Matt to obey the rules voluntarily, not have a fight every night.

After taking a deep breath, I spoke again, this time in a calm voice. I told Matt I was sorry that I'd shouted at him. I was very tired, I explained, but that was no excuse for taking it out on someone else. When I saw that he was opening up a bit, I stopped talking and asked him what was going on. Why was he still up an hour past his bedtime?

Reaching under his blanket, he slowly pulled out a book. "Because I'm at this really exciting place in my book and I just couldn't stop." His response stunned me. I had been convinced that his only goal was to defy me, and it had nothing to do with me! More important, he wasn't playing video games or watching TV; he was reading, something I very much wanted to encourage.

Nevertheless, we still needed to address my concern over his getting enough sleep. I explained to him why I felt it was important for him to go to bed at 10:00. "You have to get up by 6:30 to get ready for school in time to catch the bus. Lately, you've been complaining of headaches. I believe it's because you're not getting enough sleep. At your age sleep is important so that you'll be healthy, grow strong, and do well in school. Besides, I don't like seeing you feel bad. I love you." To my chagrin, I saw that Matt had the same stunned look on his face that I had had a moment before. "She loves me?" I could imagine him thinking. "I thought her only pleasure in life came from yelling at me."

I then asked him what he thought we should do to resolve the problem. He proposed that he would read until the end of the chapter, then stop. Thumbing through the book, I saw that the chapter went on for quite a few pages more. "I don't think that will work to resolve the headache problem. It will take you another twenty minutes at least to read all of that. What if you just read to here?" I suggested, pointing to a breaking point a page and a half ahead. He agreed. I left the room. Five minutes later his light went out.

We never fought about that issue again.

Have you ever had a conversation with someone who was fixated on getting you to agree to her point? It's pretty irritating, isn't it? What about when someone tallies up your weaknesses or failings? Does it make you more cooperative? If negotiation is not a game, then what's the purpose in racking up all these points?

Sadly, most negotiators come in with a shopping list of points they believe they must win. "These are our standard terms." "Payment must be within ten days." "Drop your price by 20 percent, or there's no deal." "We're not even going to consider flextime." Even as embarrassing as it is to admit, "Bedtime is 10:00; no arguments!"

The problem with all of these approaches is that they are focused on specific points (terms a party hopes to secure) rather than on the outcome parties want to achieve from the negotiation. Only by broadening your perspective to consider the outcomes that might result from those terms, or from the methods you use to obtain them, will you be able to connect the dots to see the bigger picture. Before forcing down the price on a tender to rock bottom, for example, you need to consider the potential impact on the quality of materials or after-sales service. Before demanding a sky-high corporate room rate, you should think about the likely impact on the customer's willingness to book your hotel if they have other options. Before issuing a "take it or leave it" threat, you would be wise to assess the consequences of the other side actually walking away.

As we saw in Chapter Two, Enron International secured virtually all of the terms it wanted in the Dabhol deal, but the resulting outcome was a price that set off riots and resulted in a multibillion-dollar loss that helped send Enron into bankruptcy. The exporter in Chapter One who sold beef to Choi during the Asian financial crisis was 100 percent correct that Choi had failed to honor the purchasing schedule in the contract; but in pressing that point so stridently, the company lost Choi's long-term business. In my own case, while it was true that I wanted my son to get enough sleep, I also wanted him to take better care of himself without my having to nag him, to become more self-reliant and responsible, and for all of us to have a happy family life. By getting stuck on the point of the 10:00 bedtime rule, I was able more or less to achieve the first outcome but was miserably failing in all the others.

It is imperative that you look hard to see whether the specific terms you are pursuing will lead to the outcome you desire. Fundamental questions to ask include

Why do I want this term? What will it help me achieve?

Does it conflict with or imperil any of my other goals?

Are these terms implementable?

If the terms were to become public, what negative repercussions might they set off?

Several years ago, U.N. delegates from around the world gathered to give official approval to a "plan of action" on population issues. Approving any U.N. accord is a major undertaking. All the parties have to agree to every word in the document, requiring round after round of minute negotiation. Then every government has to sign off on the final version. This particular action plan was especially problematic because the policies it promoted had been negotiated during the pro-choice Clinton administration, but it was now up for ratification during the pro-life Bush administration.

To the shock of nearly all the gathered delegates, who had arrived for what they had expected to be a pro forma endorsement of a document that had already received every government's approval, the American delegation, drawn from the leading right-to-life organizations, announced that they wanted to renegotiate a number of the terms. They then produced a list of changes they were demanding, all aimed at specifying that the paper was sanctioning neither abortion nor a number of forms of birth control.

A delegate to the conference told me what happened next:

Of course everyone was horrified. It was crazy. International agreements are intentionally vague. There was literally nothing in the document that supported abortion. How could we have gotten the approval of the Muslim or Catholic countries if the document had promoted abortion or unlimited birth control? Moreover, it had taken years to get all of the member governments to sign off on the existing document. There was no way to reopen what had been accepted by all. To make matters worse, there was considerable resentment of the United States, since the initial draft had been pretty much written by Washington under the Clinton administration. Now the American delegation was refusing to endorse the agreement that their own government had drafted!

The conference was scheduled to last for three days. At the end of the second day it was clear that we had reached a deadlock. Delegates were really angry. That was a serious problem since it's a policy of this committee that every decision should be made by unanimous consensus. That night, though, I had an inspiration. If the U.S. delegation was worried that certain terms in the document, such as "unrestricted access to medical care," could be read to signify support for abortion, instead of rewriting every single ambiguous clause, we could just put an asterisk at the bottom of the first page saying, "Nothing in this document should be read as either promoting or approving abortion or unrestricted access to birth control." I ran the idea by several delegates and even those in the hard-line anti-American bloc agreed it would work. At least then we could get the document approved and go home.

But the American delegation would have none of it. They insisted on holding firm to every item on their shopping list. No compromises. By then everyone else was fed up. Finally, the chairman warned us all that if we couldn't reach a consensus by the end of the day, he would have to put the issue to a vote. It would be the first time in the committee's history that we passed a plan of action without everyone's approval. The Americans still refused to budge. So it went to a vote. The paper passed with every national delegation voting in favor except two: the United States and, are you ready? Iran. Like I said, crazy.

That evening I ran into the American delegation in the hotel bar. They were so excited. "We made our point!" they crowed. "We refused to back down. By standing up for our principles we won the moral victory!" All I could think was that they had failed in everything they had set out to do. The action plan had passed by near unanimous vote in the form they did not like. They had exercised no influence over the outcome. And by forcing a vote that they lost so roundly, they had marginalized the U.S. in a way that could have a grave impact on its influence in future international agreements. Ten, twenty, fifty years from now, that document will still be here. Who will remember the loser's "moral victory"?

The American delegates had become so fixated on winning their points that they let the outcome they desired slip out of their grip. They heedlessly rejected a compromise that would have answered their concerns and retained their influence. By their single-mindedness they lost the support of even their staunchest allies and found themselves alone in a corner with Iran. Perhaps when you are as mighty as the U.S. government (or as isolated as Iran) you can afford such losses. Most of us, however, cannot.

Point-winning contests don't just divert our attention from our desired outcomes. As the above example shows, they also mire us in conflict that, as it grows more heated, blinds us to creative and effective solutions. We blame the other party for being unreasonable and dig in even further. Negotiation becomes a private battle for victory.

This can happen so easily. Imagine that you and I are in a room having a meeting. As we are talking, I walk over and casually open the door, then return to my seat. If you don't want the door open, you will feel annoyed. Not only does the open door bother you (there was, after all, a reason you had initially closed it), but you feel that I have behaved discourteously by pursuing my personal desires with no consideration for your opinion. You take my actions as evidence that I am self-interested and pushy. Of course, you may be entirely wrong. I may have responded automatically to a physical stimulus, such as feeling uncomfortably warm, while my mind was elsewhere. But unless we have a good enough relationship for you to give me the benefit of the doubt, you'll probably opt for the unfavorable interpretation.

What would happen if you were to act on your negative feelings by mirroring my behavior and walking over and closing the door? It would surely set off a reciprocal negative reaction in me. In the resulting battle for dominance—open door/closed door—one of us would have to win and the other to lose. All that door banging certainly wouldn't leave a lot of room for a mutually satisfying solution.

Does that mean that you should just sit there and stew in your juices while I dictate the terms? Of course not. The answer is to put your energy into understanding and problem-solving rather than into jumping to conclusions and fighting. Instead of immediately responding to my action with your counteraction (or my demand with your opposite demand), you would start by asking me why I wanted the door open. Was there a problem? My reply might be that I found the room so stuffy that it was hard for me to concentrate on what you were saying. From that single question and answer we would already have reached a higher level of rapport, since you appreciate what stuffiness feels like (you may even agree that the room is stuffy) and you have now learned that I have an interest in hearing what you're saying. That puts things in a different light, doesn't it?

That understanding might be enough to end things there. Or if not, you might explain to me why you wanted the door closed: perhaps people are chatting in the hallway just outside the door who are distracting you when the door is open. On seeing things from your perspective, I would feel the same surge of empathy. Your reasons make sense. More important, we realize that we both have the same larger goal; we just have different problems to be solved. You are more bothered by noise in the hallway and I by the lack of air in the room, but we both want to have a productive meeting. Now it's no longer open door/closed door—I win or you win. It has become a simple problem: how do we get more air in the room without raising the noise level? This one is solvable.

Problem-solving is the skilled negotiator's greatest asset. By getting away from positional fighting to win an "either/or" battle and instead focusing our problem-solving skills on achieving "both/and," myriads of possible solutions present themselves. We could open a window, ask the noisy people to be quiet, turn on the air-conditioning, move rooms; the list goes on. Once we put our minds to problem-solving, we are able to work out our differences in a fraction of the time and energy we would have spent fighting over who was going to win the battle of the door.

While the example of the door may seem a bit trite, it's actually the way even the most complex negotiations work at the fundamental level. You and I each have a set of goals. Where those goals don't align, we have a clear choice in how we deal with the conflict. Option one is that we could fight hard to see who emerges victorious. Frankly, if neither of us explains our reasons or makes an effort to understand the other's needs, that's the only option we have. But if we take option two—explaining our reasons, listening to one another, then working together to find a solution—we will create at least the possibility that we can both come away satisfied. Moving from fighting to problem-solving is critical because all parties have to feel that they benefit from the deal in order to work together cooperatively and productively.

Let's look at a business example. A midsized retail chain owned a warehouse in an industrial estate. Over a period of several weeks, cracks began appearing in the warehouse walls. The facilities supervisor was certain that the cause could be traced to the pile driving that was taking place at a nearby construction site. She wrote an angry letter to the owners of the new building, accusing their construction team of causing the damage and demanding that they pay compensation. How much cooperation do you think she generated from the owners of the other building?

This much: they sent over their chief engineer, who looked at the cracks, denied any possible connection to their construction project, and left.

Frustrated by the construction site manager's stonewalling, the facilities supervisor issued a series of letters with escalating demands over the ensuing weeks: the first demanding compensation; then compensation plus an admission of responsibility for known as well as any possible unknown damage; and finally, compensation plus an admission of responsibility, plus an apology. The first two letters received denials of any liability; the third got no response.

Seeing no end to the dispute, the warehouse manager took the matter into his own hands. First, he took a hard look at his goals. The biggest concern for the company was that it was planning to put the warehouse up for sale and wanted the facility to appear in tip-top shape so that it could get the highest price. In other words, it wanted the cracks repaired. That was it! The facilities supervisor had demanded compensation, an admission of liability, and an apology, but the company's real interest was to get the building on the market as quickly as possible.

Putting himself in the new building owners' shoes, the warehouse manager could appreciate that they would fiercely resist any apology or admission of liability for possible unknown damage—which could open a legal can of worms—and would stand firm against what they viewed as exorbitant compensation claims. However, they probably wanted the problem to go away as much as his company did. And they had a whole site full of construction workers and materials that might provide an easy solution.

With those thoughts in mind, the warehouse manager sent a letter to the owners of the construction site setting out the situation. It began by apologizing for the sharp tone of previous letters. Such acrimony among neighbors never benefited anyone, he wrote. He then explained the problem and the chain of events leading up to it—cracks in the walls of his company's warehouse had formed shortly after the pile driving had begun—but he did not insist that there was an absolute connection between the two. He neither cast blame nor demanded money. Instead, he asked the owners of the other building if as a gesture of neighborly goodwill they would send over some of their crew to repair the cracks.

Two days later, the site manager of the construction project called to set up a time for his crew to make the repairs. They fixed the cracks that weekend. They even repainted the exterior. Both sides were happy to resolve the issue and get back to business. (For those who ask, skeptically, "But what if there was additional damage to the foundation they didn't know about?" I would point out that nothing in this settlement would prevent the company from taking action over any problems they discovered down the road.)

Although engaging in arguments over who's right and who's wrong may have a hallowed tradition in the courtroom (and the playground), it's counterproductive at the negotiating table, where we are seeking to build mutual cooperation. Let me assure you, you can never build cooperation by forcing another party to admit to being wrong. It is much more advantageous to all to focus on how you are going to work together to solve the problem. That's genuine victory.

As we saw in Chapter Two, fairness involves creating a sense of equity. In a nutshell, not only do effective negotiators have to be able to set out clear reasons for everything they ask for, concede, or agree to, but those reasons have to be reasonable. Moreover—and this is crucial—the arbiter of what is or is not reasonable isn't the person making the offer, explanation, or request; it's the one receiving it. In other words, I have to offer a reason that you will find fair and reasonable.

For example, I may think that "This is our standard contract" is a perfectly reasonable explanation for why I am not willing to change the language in a certain clause. But chances are that you won't find it either reasonable or fair. Why should your concerns be swept aside because my company likes to use its own template?

The Singapore Port Authority undoubtedly felt that increasing rates was perfectly reasonable given its mission of providing the most high-tech facilities. But neither Maersk nor Evergreen Lines had signed on to PSA's mission. Facing an economic slump, they put a far lower priority on technology than on price. They found it unreasonable to pay to support PSA's internal decisions.

A skilled negotiator needs to be able to step back and imagine what the other side would feel is fair, to develop a measure of objectivity. I find it extremely helpful to ask myself (and sometimes the other party), "How would an impartial observer see this? Would they find this position or supporting argument reasonable?"

The ability to speak in neutral terms—not strongly biased toward your own side—will win you far more of what you want in the negotiation and far more cooperation afterward than all the rationalizations you can make for why your view is the right view. Which of the following approaches would be the most likely to get you on my side in a project management negotiation?

"We need to revise the project's division of responsibilities. All the biggest jobs have been dumped on my team. It's unfair that we have to write the manual as well. I need your team to pull more weight."

or

"Can we discuss revising the project division of responsibilities? Since half of my team has been seconded to another project, we're really stretched. I'm worried that as it stands, we may not make the deadline. Would it be possible for your team to take over production of the manual?"

The first statement may accurately reflect my point of view. I may have good cause to feel that my team has been given an unreasonable proportion of the work on the project. However, even if you could see that in a calmer light, my biased approach and accusing words would have put you on the defensive. "You don't have all the biggest jobs," you are thinking. "We do x, y, z. And what about the last project when you guys practically got a free ride? Don't lecture me on my team pulling its weight!"

The second statement gives you explanations that you are likely to find reasonable. I am not blaming you; I am explaining the situation factually. Additionally, I am showing you why you should care: if we don't redistribute responsibilities, both of us may fail to meet the project deadline. Finally, I am suggesting a solution but not imposing it on you. As a result, you will be far more likely to feel that what I am asking for is fair.

A fair approach leads to an optimal outcome because it reduces mistrust and animosity, allowing parties to focus on their common interests. While it requires patience to see things from the other side's perspective and to provide arguments that they would find reasonable, the payoff in results is well worth the investment.