Presented here is the background information from some really smart people who have written about commitment both from a team and general leadership perspective.

For anyone who has lead or worked on a team, there is a night and day difference if the team is highly committed to accomplishing its goal. With a highly committed team there is focus, energy, and a feeling that nothing will stop them from getting to the goal. To experience that is to be part of something special. If commitment is lacking the experience is painful on many fronts. So what is the difference? What do we know about commitment, engagement, and the human experience of working collaboratively? And more importantly, is there anything a leader can do to create the environment for commitment to flourish. Fortunately the answer is yes.

Employee commitment, engagement, and empowerment have been part of the leadership conversation for some time. This topic has received considerable attention because the general level of employee engagement in the United States has been estimated to be about 33 percent. I’m not aware of any research specifically focused on project team engagement but I believe it’s safe to assume that there is considerable room for improvement. I will review some key learning from highly regarded thought leaders and discuss how a project manager or leader can improve the level of engagement and commitment of a team.

Let’s start at the beginning—what is a team and what role does team commitment play?

Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith wrote a seminal book on teams called The Wisdom of Teams. Their definition is:

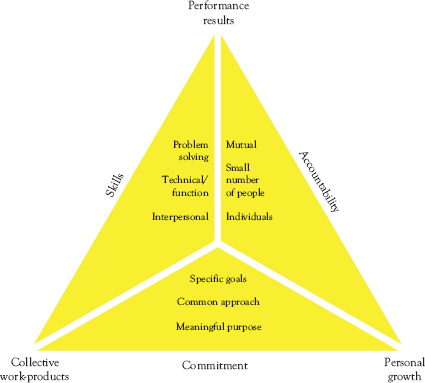

“A team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.” (Pg. 41)

Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas Smith, The Wisdom of Teams, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, 1993.

In examining their model, graphically depicted in the following, you can see that commitment is the foundation with skills and accountability enabled by a meaningful purpose, common approach, and specific goals. Without commitment the house has no foundation and it becomes unlikely that the team will succeed. A meaningful purpose addresses the “why” of the work with a common approach the “how” and specific goals the ultimate measure of success. In my experience, if a sponsor or project manager addresses these three items as part of the kick-off session most likely they are presenting this information with the team largely passive. Gaining commitment is not a passive process. I’ll talk later about how to do this differently to greatly increase the level of commitment.

Figure B.1 Katzenbach and Smith team model

Patrick Lencione, a highly regarded management consultant and author, has written extensively about teams. In his New York Times best seller, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Lencione states that team dysfunction is comprised of the following components:

1. Absence of trust

2. Fear of conflict

3. Lack of commitment

4. Avoidance of accountability

5. Inattention to results

All five are connected and unfold from the top down. The dysfunction begins with a lack of trust among team members. Without the ability for team members to engage in authentic conversation it becomes impossible to build trust. Without trust a fear of conflict surfaces—team members can’t be sure of where others are coming from or if they have ulterior motives. It becomes a very political environment, which ultimately creates a corrosive group environment where self-interest becomes more important than serving the greater good.

He also talks extensively about what trust looks like in practice.

The kind of trust that is necessary to build a great team is what I call vulnerability-based trust. This is what happens when members get to a point where they are completely comfortable being transparent, honest, and naked with one another, where they say and genuinely mean things like “I screwed up,” “I need help,” “Your idea is better than mine,” “I wish I could learn to do that as well as you do,” and even “I’m sorry.”

At the heart of vulnerability lies the willingness of people to abandon their pride and their fear, to sacrifice their egos for the collective good of the team. (Pg. 27)

And finally:

Achieving commitment:

People will not actively commit to a decision if they have not had the opportunity to provide input, ask questions, and understand the rationale behind it. Another way to say this is, “If people don’t weigh in, they can’t buy in.” (Pg. 48)

Lenciones’ prescription is clear…for teams to be effective the “soft stuff” must be actively attended to. A leader is responsible to lead by example—creating a supportive environment for the team. It’s then up to each individual on the team to have the courage to be vulnerable—to push through the discomfort and connect.

Patrick Lencioni, The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business, Jossey-Bass, 2012.

Peter Block, Flawless Consulting, 3rd Edition

Peter Block has also written extensively about how a leader can authentically connect with team members. He stresses that the leader’s task is to demonstrate or model authenticity and openness in every interaction with the team. This begins at the very first meeting. He writes…

To open a conversation or gathering, describe the concerns that began the process, define where the change effort is at this moment, describe what the organization needs from us right now, and give some idea of the structure of this step.

Most of us are familiar with the need for this kind of information. The key is to tell the whole story. This includes weaknesses and failure. Don’t protect people from the bad news in the name of protecting them from anxiety. Anxiety is a natural state, best handled in the light of day. The only caution is to keep it short and informal, with more from the heart than head. (Pg. 263)

The beginning of a project is the best time to get the team members involved and active. The opportunity is to have a real, complete conversation about the work ahead. Every major project has inherent in it positives and negatives. To present only the upside smacks of manipulation to those around the table. A mistake leaders often make is to avoid discussing anything negative so as not to poison the project from the beginning or that someone will bring up an issue that has no ready answer. Unfortunately by not presenting a complete picture the audience is left with the feeling that they are being sold. Block writes:

Human systems are not so orderly, and many doubts go unanswered. In creating high engagement, it is the expression of doubt that counts, not its resolution. We cannot construct a plan that eliminates all doubts, but we can always acknowledge them. We can acknowledge cynicism and make room for it without being paralyzed by it. The fact that the most alienated people in the organization are given a platform to speak does more to build commitment from those watching the conversation than any compelling presentation or financial incentive program ever can. (Pg. 267)

Commitment is ultimately chosen by each individual team member. It cannot be mandated nor bought. This judgment is an emotional one—it drives off of the feeling we have as a result of the interaction with the team leader and members. If transparency, authenticity, and openness are not encouraged and reinforced, commitment will suffer. It takes courage and self-awareness to step into this conversation and through the discomfort. If one makes the effort the rewards are great.

Too often our interactions with project teams come from a compliance perspective. We revert back to the expectation that people on the team are being paid to do a job and should follow through with energy and excellence. This transactional perspective leaves no place for commitment…nor does it address the human emotions that are fundamental to exceptional performance. Commitment by its very nature is emotional—it speaks to a psychological bond to a project, the team members, and the organization. It’s our job as project leaders to not lose sight of this fact and to make time to address it.

“Seven key features for creating and sustaining commitment,” Rachel Burgess and Suzanne Turner, 2000, International Journal of Project Management, Pergamon, 225–233.

Burgess and Turner have done a fine job of thinking about how best to create commitment in project teams. They argue that creating commitment is an inside-out job:

Commitment requires the internalization of the organizations values, norms, and goals to a point where there is a strong correlation between them and the individuals’ beliefs. This level of congruence builds an intense sense of loyalty and dedication, and will make employees both satisfied and productive by their involvement within the organization.

The authors outline seven key features of high commitment:

1. Individuals join of their own free will

• Members of project teams should have a choice about being part of a project team. If they disagree with the premise or objective they can decline with no repercussions. If they choose to quit after the project is underway there is no road back to this team.

2. The role of uncertainty

• Uncertainty plays an important role in laying the foundation for change, before the project can begin employees must be freed from their commitment to the past:

○ Nothing stops an organization faster than people who believe that the way they worked yesterday is the best way to work tomorrow. To succeed, not only do your people have to change the way they act, they’ve got to change the way they think about the past. (24)

Madonna J., cited in Blanchard K. and Waghorn T., Mission Possible, McGraw-Hill, 1997.

This begins with the business case for change, which is discussed in the opening team meeting.

• This also affords the team, and each member, the opportunity to create the future organization. This creates a sense of validation that they’ve been chosen for this important task as well as anxiety—can this be done? Success is not guaranteed. The anxiety stems from the importance of the task and the possibility that it may not be successful. Failure has both individual as well as organizational implications. Both energies are useful in opening the team up for the creative work to come.

3. Start small and build up

• It’s important to have a clear place to start in order for the work to begin successfully. This can be accomplished as the team moves into the initial work of discovery. The short story of discovery is that the project requires each team member to contribute knowledge and perspective about the current state. This typically proves to be very affirming because they share their expertise with the group. This begins to form the team as people share and others get a sense of the contributions and talent on the project team.

4. Joining requires individual effort

• Being part of this project comes with a very real challenge and cost. Most projects have upward visibility—either to higher functional levels or in some cases to the executive team. Participation offers the chance for recognition or a very visible failure—both having potential career implications. Additionally, in mid-size and smaller organization working on a project is in addition to their “regular job”—they have to figure out how to make it all happen successfully. This energy supports commitment.

5. Public acts of commitment

• There is a psychological concept that comes into play that can easily be used by leaders or project managers to help develop commitment. The concept is that we all want to appear to our peers as consistent beings. When our actions and words diverge it creates something called cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is uncomfortable and human nature is such that we tend to avoid or move away from uncomfortable feelings. Some simple techniques are:

○ When key decisions are made each person should be asked in the team setting…“Are you committed to this decision?”

○ Being the “public face” of the project to their functional area for input and ongoing communication.

○ Asking individual…“what are you going to do differently?”

○ Performing a process check at the end of each team meeting to get their feelings about the project and its current state. This allows an opportunity to express any doubts, concerns, or positive statements about the team’s progress. I also often ask the team for any thoughts they have about changes to our process.

The idea is that once a person declares a public position or point of view they will tend to stick with it so as not to appear inconsistent and have to deal with cognitive dissonance or uncomfortable questions from team mates.

6. Active involvement

• If the team is truly empowered to come up with a solution—they are creating it. Whenever possible team members should be given decision-making ability or authority. Decisions are the ultimate expression of organizational power. The act of deciding results in ownership and commitment.

7. Clear messages and clear lines of communication

• It’s important for the channels to open up, down and sideways. Any impediment to this flow of information or clarity slows the team down and creates frustration.

I’ll leave you with a quote from Peter Senge:

The committed person brings an energy, passion and excitement that cannot be generated if you are only compliant, even genuinely compliant. The committed person doesn’t play by the rules of the game. If the rules of the game stand in the way of achieving the vision, he will find ways to change the rules. (5)

Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline, Century Business, 1990.