CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS CULTURAL AGILITY—AND WHY IS IT SO CRUCIAL TODAY?

Within any global organization, it is the people—the human talent—who are actively engaged in assessing global risk, interacting with government regulators, and responding to unexpected shocks to the market, as well as handling mergers and acquisitions and the day-to-day management of global subsidiaries, teams, joint-venture relationships, and the like. The organization’s human talent is building credibility and trust with foreign partners, vendors, clients, contractors, subordinates, and peers. It is through global professionals that the organization builds its knowledge of customs, norms, languages, legal systems, and other cultural capital. Ultimately, the organization depends on its global professionals to make it increasingly more competitive in the global economy.

With that in mind, take a moment to think about the global professionals in your own organization. Even though they are critical to your organization’s global competitive advantage, they might also be at the heart of your business problems. When over one thousand CEOs in more than fifty countries were surveyed, “managing diverse cultures” was one of the top concerns they cited for the future.1 A significant number of the CEOs in this survey indicated that their organizations’ ability to be effective in this increasingly complex global environment is challenged by cultural barriers, such as cultural issues and conflicts, conflicting regulatory requirements, unexpected costs, stakeholder opposition, and—most central for this book—inadequate supply of talent to compete. Global business professionals—with responsibilities as diverse as market expansion, product innovation, and postacquisition integration—are technically and functionally gifted, but may lack the cultural agility needed for the task at hand.

Expansion abounds for organizations in every sector as global growth becomes the key to their future success. Across organizations, the time is right for investing in cultural agility. Global business growth is the way to win the future, and this growth depends on the strategic management of human talent. A 2011 survey of more than seven hundred CEOs found that talent management is one of the most critical vehicles for implementing global business growth strategies for the future.2 Business leaders know that they need to invest in their strategies for managing talent if they are to win in more complex global environments, such as emerging markets.3 There is widespread agreement among CEOs and other senior executives that talent management is critically important in formulating successful global growth strategies. It is time to deliver the talent management practices to empower your organization to win the future.

Talent management is one of the most critical vehicles for implementing global business growth strategies for the future.

CULTURAL AGILITY: A MEGA-COMPETENCY WITH THREE LEVELS

Cultural agility is the mega-competency that enables professionals to perform successfully in cross-cultural situations. All of us possess some level of cultural agility even before working in another culture or with people from different cultures. The idea of cultural agility follows from the common understanding of physical agility. Fitness experts describe agility as the ability to change the position of one’s body rapidly and accurately without losing balance. Think about the natural differences among beginners in a yoga class: some are more naturally nimble, coordinated, and athletic. Depending on their natural abilities, these individuals will have different experiences in the class—some will feel exhilarated, some encouraged, and others very discouraged. If they continue with subsequent classes, all will improve their agility over time, though they will develop at different rates. Cultural agility works in the same manner. Professionals will develop their cultural agility differently depending on their international career orientation, personality characteristics, bio-data (including nonwork cross-cultural experiences), language skills, and cross-cultural competencies.

You have probably admired the agility of prima ballerinas, Cirque du Soleil performers, and professional football players making awe-inspiring goals in the final seconds of a game. Watching them in motion, you may be tempted to believe they were born with their godlike bodies and superhuman physical abilities. But you probably also know that years of training and unrelenting hours of practice have blazed clear neural pathways between their minds’ commands and their bodies’ movements. In truth, both nature and nurture play a part: these individuals’ elite level of physical agility is a combination of natural abilities, motivation to succeed, guided training, coaching, and development over time. Cultural agility, as this book describes, is gained in the same manner—by combining individual skills and abilities, motivation, and experience.

Culturally agile professionals succeed in contexts where the successful outcome of their jobs, roles, positions, or tasks depends on dealing with an unfamiliar set of cultural norms—or multiple sets of them. These professionals might be aid workers operating in rural communities in developing nations, or professional athletes playing for teams located in a different country. They might be research scientists working in colocated multicultural research teams, or international assignees living and working in a different culture. They might be call center operators who are speaking with customers located in another part of the world, or professionals who are selling their products or services to clients from different cultures. Although a myriad of technical skills are necessary and will clearly affect performance, those technical skills are oftentimes not sufficient for success given the cross-cultural context of the role. For global professionals, performance depends on not only the content of their jobs but also on their ability to function in the cross-cultural context of their jobs. Cultural agility enables technically competent professionals to be successful irrespective of the multicultural or cross-cultural context.

For global professionals, performance depends on not only the content of their jobs but also on their ability to function in the cross-cultural context of their jobs.

Cultural agility is a practice, not an achievement, and building it is a process, not an event. For this reason, development is a concept closely related to cultural agility. The one is a route to the other. By ensuring that the cross-cultural experiences your professionals are exposed to are truly developmental, you can increase the cultural agility in your organization’s talent pipeline.

Whatever their job titles or roles, culturally agile professionals are able to accurately read the cross-cultural or multicultural situation; assess the differences in behaviors, attitudes, and values; and respond successfully within the cross-cultural context. Success in a cross-cultural context is the most important indicator of a professional’s cultural agility. Culturally agile professionals achieve success in multicultural, international, and cross-cultural situations by leveraging three different cultural responses:

Cultural adaptation is used at those times when adapting one’s behavior to the norms of the context is critical. Cultural minimization, in contrast, is used at times when one’s own cultural norms need to supersede the cultural expectations of others. Cultural integration is used when finding a compromise is most important and well worth the effort. Successful culturally agile professionals are adept at toggling among these three responses.

The cross-cultural competencies that culturally agile professionals possess facilitate their effectiveness in three important ways:

Collectively, cross-cultural competencies constitute the first-level indicator of cultural agility (depicted as the base of the pyramid in Figure 1.1), a foundation on which the higher-level competencies are developed.

FIGURE 1.1. The Levels of Cultural Agility

THE NEED FOR SPEED IN BUILDING A PIPELINE OF CULTURALLY AGILE PROFESSIONALS

The demand for culturally agile professionals continues to accelerate in the twenty-first century as many organizations track a substantial increase in the percentage of profits generated outside their home countries. In the United States, despite its large domestic market, emblematic American companies such as Avon, Dow Chemical, and PepsiCo reported that 80 percent, 68 percent, and 45 percent of their revenues, respectively, were generated outside the United States.4 This growth in international markets is resulting in an ever-increasing mix of people from different countries and cultures—partners, clients, customers, and colleagues.

A survey of global industry leaders found that expanding global customer reach to new emerging markets and engaging in successful mergers and acquisitions are among organizations’ leading global business strategies.5 This enthusiastic pursuit of global expansion, though clear and logical on paper, is not without problems and risks. Paul Clark, Ernst & Young’s insurance sector leader for Asia-Pacific, aptly noted that when operating across countries, especially in emerging markets, business challenges become “compounded by the problems of working in foreign countries, including customs, culture, language, and different regulatory systems and working practices.”6 Such problems can also include unexpected changes in foreign government regulations, unstable political or economic conditions, currency fluctuations, insufficient collaborative technology, inadequate managerial control of a joint venture, or a much-needed associate’s refusing a critical international assignment because his or her spouse is unwilling to relocate.

Expanding global customer reach to new emerging markets and engaging in successful mergers and acquisitions are among organizations’ leading global business strategies.

But despite the challenges, risks, and ambiguities of global growth, its opportunities remain a powerful draw for organizations, which continue to expand their operations internationally at an unprecedented rate. To help navigate around or mitigate these potential challenges and risks, organizations rely on successful global professionals who can operate effectively in cross-cultural and international environments. I’ve not met a high-level leader in any industry who doesn’t see cultural agility as a key factor for future success. On the contrary, I’ve found unanimous agreement that their organizations’ global growing pains would ease if they had access to a robust pipeline of culturally agile professionals. The question is how to develop this pipeline—and how to do so quickly. In this book, I outline how to implement the most critical talent management practices to attract, recruit, select, train, and develop a culturally agile workforce.

The shortage of professionals with cross-cultural competencies is a concern shared by military leaders as well as corporate executives. The U.S. Army, for example, has been unambiguous in emphasizing the extent to which cross-cultural competence is needed now and in the future. The Army Culture and Foreign Language Strategy (released in December 2009) states that “Today’s full spectrum operations require adaptable foreign language and cultural capabilities to be fully successful. Existing education and training programs and initiatives are helping to meet some needs, particularly for specialists, but do not meet the full needs of the Army. Closing the gaps in culture and foreign language capability requires addressing two major areas: building unit capability and expanding the scope of leader development.”7

If you remove the words “the Army” from this passage and replace them with the name of your organization, you are likely to have an accurate summary of your organization’s current state and future need for cultural agility. Although the professional roles of your associates are different from those of the soldiers and leaders in the U.S. Army, the need for cultural agility is the same. The global economy is also creating the need for companies to cast wider nets to source the best for their organizations, whether that means the best supply chain partners or the talent for the most critical roles. From professional sports leagues to executive suites, a global “best player” model is emerging. In the U.S.-based National Basketball Association, the number of foreign-born players has tripled since 1990; the number of international players in Major League Baseball is now roughly 30 percent.8 In the boardrooms of major organizations, the same pattern emerges. Roughly two-thirds of organizations have members of their global management boards who originate from countries outside the organizations’ home market.9 The ranks of top management have also been opened to foreign-born nationals. This is a relatively new phenomenon, as global diversity in this realm was practically nonexistent as recently as the mid-1990s. Such CEOs as Howard Stringer (Sony), Indra Nooyi (PepsiCo), and Carlos Ghosn (Nissan and Renault) exemplify the trend toward having the global best players on executive teams.

In 2005, I published a study with Mila Lazarova and Stephan Zehetbauer examining whether the national diversity of top leaders (executive team and board of directors) was related to organizations’ international financial performance and global reach—namely, their foreign assets ratio, foreign sales ratio, foreign subsidiaries ratio, and foreign employees ratio.10 We found a strong positive relationship between leadership teams’ national diversity and international performance. Of course, as with all studies interpreting correlations from a snapshot in time, we cannot say which came first—the national diversity of the leadership teams or the organizations’ global performance. Frankly, for these purposes it does not matter. We know that in either case the trend is interesting, growing, and unlikely to reverse itself. The most likely explanation of our findings is that broadening global markets allow organizations to be more receptive to the presence of nonnational executives. Leaders today, now sharing the executive suite with leaders from diverse national backgrounds, will clearly need a greater amount of cultural agility than ever before.

Of course, it is not only corporate boards, top management teams, and professional athletes who are working with greater numbers of colleagues from different cultures. Globalization is affecting almost every worker today. According to a recent U.S. Census Bureau report, 12.3 percent of U.S. residents are foreign born—up from just 5 percent in 1970—and over 80 percent of these foreign-born individuals are of workforce age (eighteen to sixty-four).11 This integration is not limited to the melting pot of the United States; the United Nations Global Commission on International Migration reported that 191 million people are living in a country other than where they were born. Comparing this figure with the world’s population of 6.5 billion yields the global picture: worldwide, about one person in thirty-five is living and working in a foreign country.12

Today more than ever, professionals are not only working with people from different countries but also relocating to foreign countries as international assignees. More than 60 percent of global mobility professionals from companies headquartered all around the world expect their numbers of international assignments to increase in the coming year.13 Twenty percent of these organizations reported having more than five hundred international assignees located around the world. And those are only the people who reside in foreign countries. We also need to consider the thousands who travel to other countries for business, whether to attend a meeting, conference, or training course for a few days or weeks, or who are in a position that requires substantial business travel or is colocated in multiple countries.

Many people assume that with the substantial investment in collaborative technology, such as multisite video and Web-enabled meetings, international business travel has been decreasing. In fact, international business travel is still on the upswing. Even though 79 percent of 350 global travel managers (those who manage corporate travel budgets) identified “cost control” and “reducing the overall level of spending on travel” as the greatest challenges facing business travel programs, 54 percent of them expect their business travel volumes to increase in the coming year as they have in the past.14

Without ever leaving their home countries, millions of professionals communicate across national borders in the daily course of their jobs. While their bodies are located in their home countries, their voices and words are heard and read all around the world, sometimes in many countries the same day. Combining this with the international migration statistics, we can clearly see that cultural agility is crucial not only for business travelers and international assignees but also for professionals working in their home countries. The need for cultural agility is growing exponentially, touching more professionals today than ever before.

Cultural agility is crucial not only for business travelers and international assignees but also for professionals working in their home countries.

BARRIERS TO CREATING A PIPELINE OF CULTURALLY AGILE PROFESSIONALS

Before you can develop the practices to effectively build a pipeline of culturally agile professionals, you will need to first identify the barriers that could prevent their success within your organization. These barriers are the erroneous assumptions held by leaders and managers in your organization; they affect how cultural agility is created and developed. If not addressed, these barriers could prevent your organization from successfully investing in and ultimately building a pipeline of culturally agile professionals. The four greatest barriers are

- Assuming that one possesses cross-cultural competence after only limited exposure to countries or cultures. This assumption produces overconfidence in one’s culture-specific knowledge when it is in fact merely superficial.

- Assuming that one success in a prior global or multicultural role means cross-cultural competence has been achieved. This assumption produces succession plans in which talent is “anointed” as having cross-cultural competencies when they might not exist.

- Assuming that observed or perceived similarities indicate deeper cultural similarities. This assumption produces an overestimation of commonalities and an underestimation of the influence of cultural differences among people, practices, and principles.

- Assuming that technology transcends cultural differences. This assumption produces an overreliance on technology to solve cultural challenges in communications and collaboration.

Before you can fully explore the best possible talent management practices for building a pipeline of culturally agile professionals in your organization (or convince others in your organizations to be part of this workforce solution), you will need to first diagnose whether your organization makes any of these erroneous assumptions or operates with any of the associated blinders, which can subtly and unintentionally stifle these efforts. In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll examine these assumptions. The remainder of the book will provide ways to address them.

Robert Weber/The New Yorker Collection/www.cartoonbank.com

Assumptions About Prior Cultural Exposure

You have probably heard at least one of the common metaphors for culture: culture as an iceberg, culture as an onion, culture as an ocean. Each of these metaphors portrays culture as having a deceptive outer surface, with the real interest, problems, and challenges hidden underneath. There is a great deal of truth in this concept. Consider the surface indicators of culture you experienced the last time you traveled to another country. In the hour or two it took to disembark from the plane, collect your luggage, ride in a taxi, check into the hotel, and go to your first meeting, you are likely to have noticed several things about the country’s culture. Before you could finish your first jet lag–inspired cup of coffee, you probably observed the style of dress, the degree of friendliness, traffic patterns, hygiene, punctuality, meeting formality, and communication style prevalent in the country where you landed. These observable behaviors—the tip of the iceberg, the onion skin, the ocean’s surface—are easy to see and feel, and relatively easy to maneuver around. The depth of the culture most business travelers experience is often limited to these observable behaviors, viewed through the traveler’s own cultural lens. The real challenges for global professionals are rarely found on the observable surface of cultures—and culturally agile professionals know this.

The real challenges for global professionals are rarely found on the observable surface of cultures—and culturally agile professionals know this.

The cultural challenges are almost always a function of deeper differences than those that meet the eye. (To experience this point through your five senses, now is a good time to go into the kitchen and slice open a strong onion.) The inner or below-the-surface culture includes characteristics or principles that are often taken for granted by those living in that culture. These below-the-surface characteristics can be divided into two categories: cultural attitudes and cultural values.

- Cultural attitudes are unspoken opinions about what is considered beautiful or ugly, respectful or rude, appropriate or inappropriate, risky or safe, desirable or undesirable.

- Cultural values are embedded assumptions that sometimes cannot be articulated, even by those who know the culture well. At the national level, cultural values may include basic principles, such as the right of independence, the privileges of birthright, the importance of the collective’s interests over one’s own, and the nature of virtues (courage, honor, integrity, and so on).

One derailing assumption among global professionals is that frequent business travel can be equated to increased country-specific understanding—more frequent travel is assumed to indicate a deeper understanding of the culture. This is incorrect. Taking multiple business trips to a given country does not necessarily make professionals proficient in that country’s culture any more than their watching many hockey games would make them proficient hockey players. Both playing hockey and developing cultural agility require some basic skills and abilities. In both cases, some contact is needed. If you asked me how many times I’ve been to Singapore, I’d pause, gaze up toward some invisible mental calendar, and probably answer “about ten.” If you ask me what I know about Singapore or Singaporeans, I’d confess that my knowledge is about as superficial as that of any typical business professional, despite my ability to maneuver around Changi Airport with the best of my fellow airport club members. Given the structure of the program for which I was a professor, my work in Singapore gave me only minimal contact with peer-level Singaporeans.

Professionals also make an assumption about the duration of time they spend in another country. International assignees in most organizations spend an average of two years in their host countries. Although two years may seem like a lot of time to benefit from what could be a developmental opportunity, many international assignees spend those two years in a cocooned environment, insulated from the host country’s culture. They often live in expatriate communities alongside their fellow compatriots. They are given market-basket allowances to buy the foods most familiar to them, regardless of the expense. They join international clubs and send their children to international schools with others who are in the expatriate community. Their work context might have cultural elements, but the office environment tends to be a hybrid of the company’s corporate culture and the national culture, swayed more heavily toward the corporate culture with the increased number of international assignees. The typical experience of a foreign assignment can do little to change or improve cross-cultural competencies or build cultural agility.

If you have learned to speak a second language as an adult, you’ll appreciate the parallel assumption individuals make when they become overconfident in their language skills after advancing to an intermediate level in the new language. They know proper pronunciation and can form grammatically correct sentences. However, the minute they engage in conversation with a native speaker—especially over the phone—they are quickly overwhelmed. The native speaker talks too fast, uses sentence structure that is too complex, uses too many colloquialisms not found in the textbook, and may have an accent different from the pronunciation formally taught. After such a humbling experience, new language learners will recalibrate their perception of their level of fluency.

Frequent business travelers and cocooned international assignees might believe they have become “fluent” in the foreign culture when in fact they do not yet understand cultural nuances. A deeper understanding of the attitudes and values of the culture is developed through personal and professional peer-level contacts and far deeper experiential opportunities, which are not often present when one is on the typical business trip or international assignment. Unfortunately, the lesson in overconfidence comes more slowly than it does in our language example, and there are fewer opportunities for recalibrating humbling experiences.

Assumptions About Prior Success

This second assumption follows on the heels of the first, but focuses not on what individuals believe about themselves but on what leaders in organizations believe about their employees who are frequent business travelers and international assignees. To understand the root of this assumption, we need to recognize that organizations typically grow increasingly more global, not less so. As their operations and market share become more international and cross-cultural, the roles and positions occupied by their strategic talent require more global responsibilities. Talented professionals who are successful in their domestic context are assigned to spearhead the international expansion of their functional areas, business units, or global teams. This is the natural career progression in most organizations’ talent management programs: highly capable associates within the organization, those outstanding in their respective technical or managerial functions in the domestic context, are invited to do what they do best—only this time they are expected to do it in an international or multicultural context.

Unfortunately, what unfolds next is central to the reason why, after decades of global growth, companies still lack the culturally agile professionals they desperately need today: associates’ initial cross-national or multicultural assignments are generally considered developmental or “stretch” roles because of their expanded responsibilities. Some professionals are wildly successful in these roles. Others crash and burn. Most are somewhere in between. Those who are generally successful in those initial cross-cultural or multicultural roles are organizationally anointed, assumed to have cross-cultural competence, and moved into the global talent pool.

If these anointed professionals go on to be less successful in subsequent international or multicultural roles, their cross-cultural competence is usually not questioned. Instead, their professional shortcomings are addressed with a focus on functional or managerial competencies. Minimal, if any, attention is paid to the development of cross-cultural competencies because, according to conventional assumptions, they have already earned that merit badge. These professionals, in the name of development, are sent to university-based residential executive development programs, given coaches for additional functional or leadership improvement, or shifted to a different role, citing a “bad fit” with a given role.

Do you think this is an assumption made in your organization? Try this diagnostic: ask your colleagues to name professionals in your organization who they consider to be knowledgeable about a given country or culture. Once a few names have surfaced, ask “Why?” You are likely to hear such responses as, “He spent a lot of time flying to France to work out the bugs in the Big Technical Integration” and “She was in Australia for six months as part of the Really Big Merger deal last year.” In today’s corporate halls, business trips and international assignments accumulate like knowledge chips. Although international business travel and international assignments can be highly developmental (more on this in Chapters Seven and Eight), the talent management metric for judging cultural agility should not be frequency or duration of trips to a foreign country.

Assumptions About Cultural Similarities and Differences

A third barrier to creating a pipeline of culturally agile professionals is an assumption on the part of individuals who travel or live abroad: they are often blinded by (or comforted by) the similarities they experience around the world. More than twenty-five hundred years ago Socrates proclaimed, “I am not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world.” Today many business executives are “citizens of the world” in the most superficial sense. They know how to find a good sushi restaurant when traveling in Europe, order French champagne in South America, and have a European fitted shirt tailored in Asia. They know their way around airport clubs and duty-free shops. They share business-class cabins, English language fluency, affluence, and often a common educational background with their global professional peers.

Consider the common experience of education. Leading business schools offering International MBA degrees, such as the London Business School, Hong Kong UST Business School, and INSEAD, boast that over 90 percent of their students come from countries other than the country in which they are studying. In leading International MBA programs in the United States (Wharton, Harvard, Stanford, MIT, University of Chicago, and Columbia), about 50 percent of the students are not American.15 The experience of attending a leading business school can be a powerful socializing agent, shaping attitudes as well as behaviors. For most, it is a bonding experience: classmates share meals, knowledge, and class notes. They collaborate in teams to complete class assignments, resolve interpersonal conflicts, and celebrate graduation with the same wide smiles and sense of accomplishment. For these students, the business school experience fosters the development of some cursory cross-cultural competencies in a controlled and institutionally supportive environment.

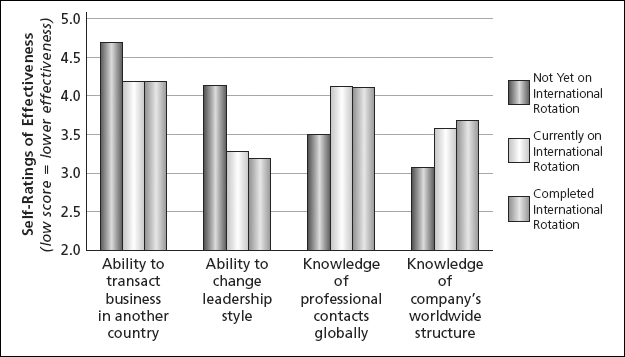

But are these International MBA graduates culturally agile? Victoria DiSanto and I conducted a study looking at newly minted International MBAs who were selected for global leadership rotational programs in three leading U.S.-based organizations.16 In each of the programs, which represented three different industries (financial services, pharmaceuticals, and consumer products), one of the rotations would be an international assignment lasting six to twelve months. Across the three organizations, the groups were evenly staggered: one-third of the MBAs were on their international rotation, one-third had not yet started their international rotation, and one-third had completed their international rotation. These were graduates of the world’s leading International MBA programs, with the heaviest representation from INSEAD, Wharton, and the London Business School. Approximately 35 percent of the participants in this study were from the United States; the remaining 65 percent were from eighteen other countries. Many were multilingual (60 percent were fluent in two languages) and rather well traveled (50 percent had lived in another country for longer than a year prior to accepting the position in the rotational program). As a group, the participants in our study were already cross-culturally competent business professionals—or so we thought. But when we analyzed the data, a different picture emerged.

We asked our participants to self-rate both their knowledge and their abilities to conduct business in another country. This was the surprise: the group who had not yet been on their international assignment rotation rated themselves significantly higher than the other two groups in terms of their abilities. As Figure 1.2 illustrates, the group who were currently on the international rotation and the group who had already completed it both rated their cross-cultural abilities lower in comparison.

FIGURE 1.2. Self-Ratings of Abilities and Knowledge from Global Rotational Programs

On the face of it, this might seem like a contrary finding—but this is hardly the case if you consider the first two assumptions. Our well-traveled International MBA graduates assumed that their combination of international travels and multicultural contacts with classmates had endowed them with a high level of cross-cultural abilities. Apparently, graduate school had lulled them into cross-cultural comfort. When the veil of the academic setting was lifted (that is, when they completed or were in the process of completing their international rotation), they were shocked to realize that their cross-cultural abilities were not as advanced as they had thought. Cultural bravado was replaced by cultural humility—and cultural humility is a highly valuable competency for global professionals to possess. This is a powerful lesson—both for their own development of cultural agility and as future advocates of programs to build cultural agility in the workforce.

Cultural bravado was replaced by cultural humility—and cultural humility is a highly valuable competency for global professionals to possess.

This is not to say that the experience of the International MBA program didn’t start them at a more advanced level. It did. Graduates from elite business schools possess a deeper knowledge than most on issues of international business. As our study also illustrated, and as you can see from Figure 1.2, the participants built on their existing base of knowledge and gained additional international knowledge from having had the experience of the international rotation.

Like elite business schools, regional headquarters and foreign subsidiaries of global organizations often engender perceptions of cultural similarity. A study by Jan Selmer and Corinna de Leon illustrates this point.17 These researchers studied the work values of middle-level Singaporean managers working for the Singaporean subsidiaries of Swedish organizations and compared them with Swedish managers in Sweden and Singaporeans working for non-Swedish organizations. They found that Singaporean managers working for Swedish organizations adopted some of the Swedish work values, including the preference for less tension and stress on the job, good physical working conditions, and cooperation between colleagues—and differed from their compatriot Singaporean colleagues working for other organizations. The Singaporeans had acculturated to the Swedish ways of working, making it rather easy for Swedish business travelers visiting their Singaporean subsidiaries to perceive cultural similarities. From the familiar logo on the wall to the shared corporate values, the workplace environment can be a strong socializing influence. Global business professionals who spend much of their time in their own company’s subsidiary locations may erroneously perceive more similarities than actually exist between cultures. These cultural similarities are real; that’s not the problem. The problem occurs when these perceptions of similarity are taken to another cultural context.

Among well-traveled and well-educated professionals, the need for cultural agility is masked by the common reality they share with their fellow cosmopolitan business executives. It is easy for them to overestimate the commonalities among people because their experience is, rather legitimately, one where differences are minimized. Although these commonalities help bridge the cross-national differences between these professionals within their own cultural microcosm, the greatest challenges for global business tend to exist in the “real world” outside that sheltered environment.

Assumptions About Technology

Consider all the communication, conferencing, and collaborative management and coordination tools your organization uses regularly, from the ubiquitous voice mail and email, texting and instant messaging, conference calls and videoconferencing to the highly sophisticated project management and knowledge management systems. Chances are high that the use of them in your organization is substantial—and that their use is increasing every year. When almost four thousand managers from all around the world were surveyed on their organizations’ use of unified communication and collaboration technology, nearly 40 percent of them reported that their organizations will increase spending on these tools.18 Of the organizations that have not yet deployed communication and collaboration tools, more than 80 percent plan to deploy them in the next two to three years. We are clearly becoming a more interconnected world.

Many of these elaborate communication and collaboration systems are sold with the promise of reducing travel costs, improving speed and effectiveness of collaboration among geographically dispersed associates, and dissolving national borders by creating a virtual meeting space. Are these claims true? Cristina Gibson and Jennifer Gibbs conducted an extensive study with 266 engineers who were members of fifty-six aerospace design project teams.19 The teams each had between four and ten members, scattered around countries and various project sites. Collectively, the teams were part of an umbrella project worth about $200 billion; their innovations were clearly critical to the success of the organization. The teams varied in national diversity and geographic dispersion—but they also varied in their reliance on electronic communications (email, teleconferencing, and collaborative software).

The results were staggering. National diversity and geographic dispersion reduced the project teams’ innovation. But what about the use of electronic communications? Surely that must have helped the team members catch their collaborative stride? On the contrary, the greater the cross-national teams’ reliance on electronic communications, the less innovative they were.

The greater the cross-national teams’ reliance on electronic communications, the less innovative they were.

What ultimately yielded the most innovative results in the work of these culturally diverse project teams? It was their interpersonal relationships. Specifically, the teams that had created a psychologically safe communication climate were the ones with the highest product innovation. In a psychologically safe climate, team members trusted each other and believed they could express their ideas, talk through the problems they encountered, and be assertive about their thoughts and feelings.

This study clearly refutes the assumption that technology can eliminate the challenges of cultural differences. In fact, it indicates just the opposite: by building trust and establishing comfortable methods for communicating and collaborating, global professionals can mitigate the challenges of technology. Among those teams with a high use of electronic communications, having a psychologically safe communication climate produced a roughly 20 percent increase in the project teams’ innovation ratings over those in a climate the members did not consider psychologically safe. It seems that overreliance on technology might be negative, but the negative effects are mitigated when team members feel good about their working relationships.

Using collaborative technology does not fully vanquish cultural differences any more than the use of English as a common business language does. When people use communication and collaboration technology, they bring with them their cultural norms for information sharing, communication, collaboration, and preferences for technology. This is evident in a study conducted by Pnina Shachaf examining the influence of information and communication technology on globally dispersed R&D teams from nine countries.20 These technology-laden team members reported that both “cultural and language differences resulted in miscommunication, which jeopardized trust, cohesion, and team identity.” It would be difficult to create psychologically safe communications with colleagues from different countries when the basic elements of trust and cohesion are missing.

The R&D team members in this study also spoke about the increased “cost of interactions”: the slower pace of conference calls and other synchronous meetings, the greater effort to write emails in clear and simple phrases, and the extra time spent clarifying the accuracy of communications for those writing and speaking in a second language. However, Pnina did find several positives for technology use. For example, nonvisual asynchronous technology, such as email, was able to eliminate miscommunication resulting from cultural differences in nonverbal cues (because you cannot react to something you cannot see) and to reduce miscommunication resulting from cultural differences in verbal communication styles (because team members spent more time thinking through what they wanted to communicate in writing).

TAKE ACTION

Based on the information presented in this introductory chapter, the following is a list of specific actions you can take to begin building your organization’s pipeline of culturally agile global professionals:

- Identify from a strategic standpoint the top five to ten ways your organization is becoming more globally integrated. For each of these, identify the key roles that will be required to operate with cultural agility. Now look at the professionals currently filling those roles in your organization. To what extent are these individuals culturally agile?

- Identify the organizational champions—in addition to yourself—who understand the importance of building a pipeline of cultural agile professionals. Have them do the same exercise described in the previous bullet point and see whether their conclusions concur with yours. As a group, can you identify your organization’s cultural agility “pressure points” from a strategic perspective?

- Review the four erroneous assumptions that stand in the way of developing cultural agility. Use them to diagnose your organization’s readiness and to identify (and remove) potential barriers to building a pipeline of culturally agile professionals.

Notes

1. PwC, 10th Annual Global CEO Survey, January 2007, http://www.pwc.com/extweb/insights.nsf/docid/46BC27700D2C1D18852572600015D61B (accessed September 7, 2007; URL is no longer available).

2. The Conference Board, The Conference Board CEO Challenge 2011: Fueling Business Growth with Innovation and Talent Development, Research Report TCB-R-1474-11-RR (New York: The Conference Board, April 12, 2011).

3. PwC, 14th Annual Global CEO Survey, January 2011, www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceo-survey/download.jhtml.

4. Percentages from the following sources: Associated Press, “Latin American Market Lifts Profit at Avon,” New York Times, May 4, 2011, B6, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/04/business/04avon.html; Indra K. Nooyi, “Is Good for All,” letter to shareholders, PepsiCo, 2010, http://www.pepsico.com/annual10/downloads/PepsiCo_Annual_Report_2010_Letter_to_Shareholders.pdf; and Jack Kaskey, “McDonald’s, Verizon Mark U.S. Profit Slowdown on Consumer Woes,” Bloomberg Businessweek, October 6, 2010, http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010–10–06/mcdonald-s-verizon-mark-u-s-profit-slowdown-on-consumer-woes.html.

5. Ernst & Young, The Ernst & Young Business Risk Report 2010: The Top 10 Risks for Business: A Sector-Wide View of the Risks Facing Businesses Across the Globe, EYG no. AU0583 (December 17, 2010), http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Business_risk_report_2010/$FILE/EY_Business_risk_report_2010.pdf.

6. Ibid., 19.

7. U.S. Army, Army Culture and Foreign Language Strategy (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Office of the Army, December 1, 2009).

8. Mariama Diallo, “International Players’ Impact on NBA Grows in Past Two Decades,” Voice of America News, February 17, 2011, http://www.voanews.com/english/news/sports/International-Players-Impact-on-NBA-Grows-in-Past-Two-Decades-116426514.html; Reuters, “Players Born Outside the United States Made up 28 Percent of Major League Baseball’s Opening Day Rosters,” April 1, 2008, http://www.reuters.com/article/2008/04/02/us-baseball-international-idUSSP8408520080402.

9. Ernst & Young, “Act Differently: Sponsor People Who Are Not Like You,” http://www.ey.com/GL/en/Issues/Business-environment/Leading-across-borders--inclusive-thinking-in-an-interconnected-world---Act-differently--sponsor-people-who-are-not-like-you.

10. Paula M. Caligiuri, Mila Lazarova, and Stephan Zehetbauer, “Top Managers’ National Diversity and Boundary Spanning: Attitudinal Indicators of a Firm’s Internationalization,” Journal of Management Development 23, no. 9 (2005): 848–859.

11. U.S. Census Bureau, “Nation’s Foreign-Born Population Nears 37 Million,” press release, October 19, 2010, http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/foreignborn_population/cb10-159.html.

12. For world population, see Population Reference Bureau, 2005 World Population Data Sheet (Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2005), http://www.prb.org/pdf05/05WorldDataSheet_Eng.pdf. See also United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Migration Report 2006: A Global Assessment: Part 1. International Migration Levels, Trends and Policies (New York: United Nations, 2009), http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/2006_MigrationRep/part_one.pdf.

13. Brookfield Global Relocation Services, 2011 Global Relocation Trends Survey (Woodridge, IL: Brookfield, 2011).

14. Egencia, 2011 Global Supply Benchmarking Research and Analysis (Bellevue, WA: Egencia, 2011).

15. Financial Times, Business School Rankings 2011 (London: Financial Times, 2011), http://rankings.ft.com/businessschoolrankings/global-mba-rankings-2011.

16. Paula M. Caligiuri and Victoria DiSanto, “Global Competence: What Is It—and Can It Be Developed Through Global Assignments?” Human Resource Planning Journal 24, no. 3 (2001): 27–38.

17. Jan Selmer and Corinna de Leon, “Parent Cultural Control Through Organizational Acculturation: HCN Employees Learning New Work Values in Foreign Business Subsidiaries,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 17 (1996): 557–572.

18. Frost & Sullivan, Meetings Around the World II: Charting the Course of Advanced Collaboration, white paper sponsored by Verizon and Cisco, October 2009. http://newscenter.verizon.com/kit/collaboration/MAW_WP.pdf.

19. Cristina B. Gibson and Jennifer Gibbs, “Unpacking the Concept of Virtuality: The Effects of Geographic Dispersion, Electronic Dependence, Dynamic Structure and National Diversity on Team Innovation,” Administrative Science Quarterly 51, no. 3 (2006): 451–495.

20. Pnina Shachaf, “Cultural Diversity and Information and Communication Technology Impacts on Global Virtual Teams: An Exploratory Study,” Information and Management 45 (2008): 131–142.