CHAPTER 5

ASSESSING AND SELECTING FOR CULTURAL AGILITY

Sudhey Taveras recalls being culturally agile as a young child, long before she could have even uttered the phrase. Sudhey, an American, was born and raised in the Lower East Side of New York City. Her parents, who are from the Canete Tenares region in the Dominican Republic, encouraged Sudhey and her siblings to become bilingual, functionally bicultural, and comfortable in multicultural environments—a lifestyle that was reinforced the moment Sudhey stepped out of her Spanish-speaking home in New York. Describing her earliest indicators of cultural agility, Sudhey recalls that “everyone I knew was from somewhere—Puerto Rico, Italy, China, Bangladesh, and everywhere in between. Among my friends, it was not only OK to be bicultural, it was celebrated. I attended the local public school which celebrated everyone’s heritage and culture. I grew up celebrating the Jewish, Chinese, and the calendar New Years. I celebrated Hanukkah, Christmas, and the Dominican Independence Day. As children, we learned to respect each other’s differences, and my school made it easy to do just that, fostering an environment which was colorful and inclusive.”

Like many of the friends from her childhood, Sudhey looked forward to spending summers with relatives in the Dominican Republic, reconnecting with family and nature. Experiencing cultures and travel became part of her life, and, as she matured, she started traveling farther afield. By the time Sudhey was in college, she had traveled all over the United States, the Caribbean, and throughout Western Europe. She would often travel alone, embracing the opportunity to meet people in different countries. Sudhey enjoys opportunities to leverage her cross-cultural competencies at work; she is comfortable in new environments, naturally finds commonalities and connects easily with others, enjoys diverse teams, and communicates well with people from different backgrounds. She is drawn to the excitement of going to new places and working with people from different cultures. I would describe Sudhey as having a high tolerance of ambiguity. She describes herself as being “sensibly fearless” of the unknown. (Well said.)

Now a successful global professional, Sudhey credits early life experiences with setting the strong foundation for her cultural agility, sharing that “from a young age I knew that I thrived in diverse and inclusive environments.” After completing her master’s degree, Sudhey was attracted to working for her employer because the organization offered her an opportunity to be on the global leadership development track, enabling her to live and work abroad. In various assignments, she has been able to travel, utilize her Spanish-language skills, and work in diverse environments.

Sudhey would describe her cultural agility as being in her blood, and credits her Dominican cadena heritage, which encourages both immigration and a communal desire to work for the betterment of the extended family, for ultimately making her the culturally agile professional she is today. Although it is true that Sudhey had significant international and multicultural experiences as a function of her heritage, her cultural agility is a combination of the many cross-cultural experiences she has had and who she is as a person. Sudhey’s motivation to succeed, her international career orientation, her language skills, and her dispositional characteristics—such as her openness, extroversion, and emotional strength—are fundamental to the person she is. For those who are truly predisposed to be culturally agile, like Sudhey, their cross-cultural experiences accelerate development.

In Sudhey’s case, the organization where she works benefited from her cultural agility from the moment she started. They selected her for her cultural agility. For organizations building a pipeline of global professionals, this is the more desirable option: to select culturally agile professionals who can be successful in cross-cultural contexts from the moment they start. The other option is to select individuals with the predisposition to develop from the cross-cultural experiences the organization offers. In other words, you have two options for developing a pipeline of culturally agile professionals: the classic “buy” or “make” approaches to acquiring human talent. A third (and rarely successful) option is to select talent without considering cultural agility and just “hope for the best” in developing the pipeline. This “hope for the best” approach is, thankfully, being employed less often as hiring managers become savvier at assessing individuals for the presence of cultural agility.

Most organizations have two talent needs when it comes to building their pipelines of culturally agile professionals. First, they need culturally agile individuals like Sudhey, who will be effective immediately in critical cross-cultural roles. These professionals have already demonstrated their cross-cultural competencies, language skills, and the like, and have shown that they are able to work comfortably and effectively with people from different cultures and in multicultural settings. They not only have experience living internationally or working cross-culturally but also have demonstrated a record of success and progressive development from their rich cultural experiences. These individuals are in high demand and, unfortunately, in short supply.

If your organization needs an immediate infusion of culturally agile professionals, I recommend redoubling your recruitment efforts as suggested in the previous chapter and raising the bar on the selection tools suggested in this chapter. The second talent need of organizations follows from the first. Your organization would be well served to select employees with the propensity to readily gain cultural agility through targeted developmental opportunities.

Select employees with the propensity to readily gain cultural agility through targeted developmental opportunities.

What if you are not sure which jobs in your organization will require cultural agility? It might be the case that certain positions require a high level of cultural agility, whereas others do not. The difference is important. To identify the jobs most needing cultural agility—and even the specific cross-cultural competencies needed—you can apply a job analysis method. Job analysis is a systematic way to identify the knowledge, skills, abilities, personality characteristics, education, experience, and competencies needed to perform a given job. See the box “How to Conduct a Cultural Agility Job Analysis” for more information on how job analysis can be used to tailor a selection system for cultural agility. Knowing the level of cultural agility needed for a given job, job family, functional area, or business unit will help you tailor your selection system with the assessment tools suggested in this chapter.

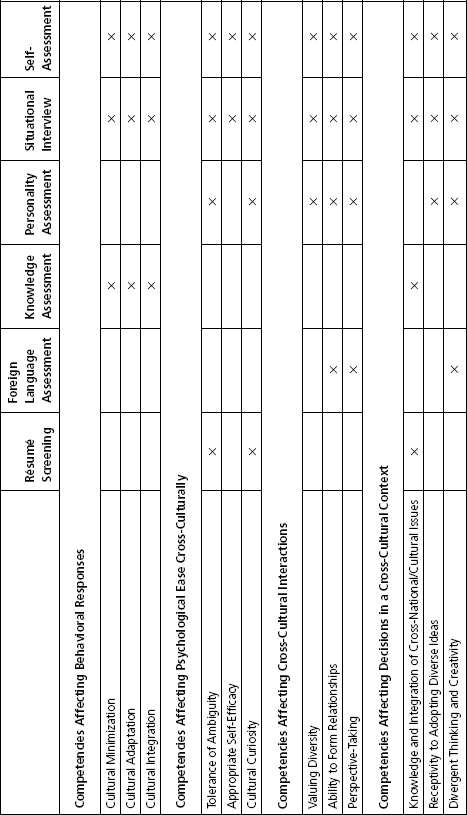

The remainder of this chapter describes the components of the Cultural Agility Selection System, including a multimethod approach for assessing the cross-cultural competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework (presented in Chapters Two and Three). Given that each cross-cultural competency has its own configuration of knowledge, skills, abilities, motivations, and dispositional underpinnings, each will require a somewhat different approach to assessment. Figure 5.1 provides a matrix for the tools included in the Cultural Agility Selection System. It also summarizes the selection methods your organization should consider using to build its pipeline of culturally agile professionals.

FIGURE 5.1. The Cultural Agility Selection System

RÉSUMÉ SCREENING

You should sensitize your recruiters, hiring managers, retained search firm partners, and even your applicant tracking systems to ways to screen résumés for evidence of the competencies related to cultural agility. Both humans and machines will likely need to work together to identify résumés of the culturally agile talent or those who have the propensity to gain cultural agility. If résumés will be “read” first by computer software, you will need to make sure that your system can detect those applicants who might have cultural agility. More than 60 percent of employers, both small and large, are using applicant tracking systems to scan résumés.1 If your organization has one of these systems, your candidates’ résumés will be read by a recruiter, hiring manager, or professional from your retained search firm only after they pass the system’s filter. The filters are keyword scans designed to detect the technical experience (usually nouns, mostly technical jargon) on the résumés. If the goal is to find those who might also be culturally agile or have the propensity to gain cultural agility, you will need to broaden the keyword filters appropriate for the position you are trying to fill. Consider some of the following categories and some sample keywords:

Following the computer scan, it will be time for human eyes. At first pass, most hiring managers will spend only between five and twenty seconds reading a résumé. Much like the applicant tracking system, they are scanning, looking for keywords, accomplishments, experiences, and skills. If you will be the one reading the résumés, look for patterns of engagement in progressively challenging cross-cultural activities. Spend more time on the résumés of candidates who have lived abroad for a significant period of time, even if the experience was not work related (for example, study abroad, volunteerism), and then sought out opportunities to work in international or multicultural situations. These activities will likely indicate, at minimum, a greater comfort cross-culturally (in other words, a greater tolerance of ambiguity and more cultural curiosity), given that humans rarely seek out perpetually uncomfortable situations.

Scan résumés for a self-reported indication that your candidates have fluency in foreign languages. Then look more closely for any opportunities the candidates may have had to actually use those foreign language skills. For example, a candidate who is not from Germany who lists on her résumé fluency in German and also lists that she lived in Germany as a student and works for a German company should be considered more closely than someone who merely lists fluency in German. A diversity of experiences where the candidates’ language skills were used suggests that they would likely possess a greater level of, at the very least, some country-specific knowledge beyond their home countries.

FOREIGN LANGUAGE ASSESSMENT

Being able to converse with people in their own language improves one’s chances of forming relationships and working effectively in a country where that language is spoken. (I realize that this sounds like it might best belong in the Journal of Obvious Conclusions, but it is often an overlooked issue when companies send professionals to different countries for work.) If the goal is to form relationships with peers, subordinates, partners, or clients whose first language is not English, having proficiency in their language does, in fact, help. It allows others to clearly convey their thoughts in their first language, even if they are reasonably proficient in English.

Beyond this somewhat obvious benefit of improved communication, there are additional benefits of selecting bilingual individuals into your organization. Fluently bilingual individuals have a variety of cognitive advantages over their monolingual counterparts. Numerous research studies have demonstrated the link between bilingualism and enhanced problem-solving skills, cognitive flexibility, learning strategies, abstract reasoning skills, and working memory.2 The research on bilingual cognitive complexity is fascinating, especially if you are trying to improve your memory or become better at solving problems. However, most relevant for cultural agility is the research that has linked bilingual fluency to divergent thinking and perspective-taking.

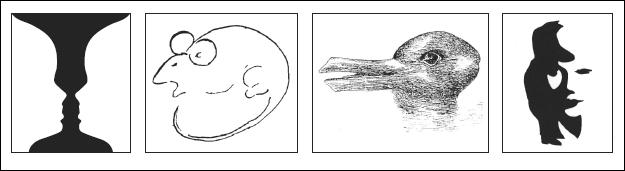

Let’s test this out. First, take a moment and stare at the images in Figure 5.2. What do you see? Hint: each image contains two objects. To see both objects, you will need to shift focus and reassign a different meaning to the same feature of the image. For example, to see the face-vase image, you will need to visually allow the chins in the profiled faces to also be the base of a curvy white vase in the center of the image. (If you are stumped, please visit www.culturalagility.com for the answers to the other three.) Ellen Bialystok and Dana Shapero found that bilingual children were better able to reassign interpretations to figures in the ambiguous images.3 In a professional context, those who can interpret the same scenario in multiple ways should have a higher capacity to suppress their original interpretations, allowing for a different interpretation to emerge (perspective-taking), and to see things in ways they had not previously considered (divergent thinking or creativity).

FIGURE 5.2. Do You See Two Objects in Each of These Ambiguous Images?

There are a variety of ways to assess foreign language proficiency (see box below). As an assessment of the ability to form relationships, foreign language tests should assess listening and speaking, ideally in the target language of the location where your colleagues will be working. The assessment of foreign language skills for the purpose of assessing divergent thinking and perspective-taking does not need a destination country. The desired candidate would be bilingual or multilingual, irrespective of the languages needed for professional communication. For this assessment, you should consider assessing both active language skills (reading and speaking) along with passive language skills (writing and listening).

Bio-data items can also be used to assess foreign language skills or the use of those language skills in various circumstances. Bio-data items are verifiable behaviors that indicate the presence of a certain attitude or trait. The premise of bio-data is that our past behavior is likely to be the best predictor of our future behavior. For example, those who have a history of trying different ethnic recipes, using unfamiliar ingredients in cooking, and so on will have bio-data evidence of a positive attitude toward ethnic cuisine. Asking these questions should be a more reliable indicator of an individual’s attitude toward ethnic food than asking directly the question “Are you open to trying new foods?” See the box “Bio-Data Assessment for Foreign Language Usage” as an example.

- Language Testing International is a licensee of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) and assesses language proficiency in over sixty languages. The ACTFL standards offer a structured rating based on the internationally recognized test of language proficiency. Visit www.LanguageTesting.com.

- The Center for Applied Linguistics also uses the ACTFL structured ratings in its Simulated Oral Proficiency Interviews to assess language skills. Visit www.cal.org.

- The United Nations (UN) has language proficiency examinations to test written and verbal skills in each of its six official languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish. These are only available to organizations related to the UN and within the UN family. Visit http://www.un.org/exam/lpe.

- Transparent Language offers free written language proficiency tests online for thirteen different languages. These are self-scoring and assess standard grammar and vocabulary. Visit http://www.transparent.com/language-resources/tests.html.

KNOWLEDGE ASSESSMENT

Think about the past five countries you have visited, either for vacation or a professional activity. For each, are you able to name the country’s capital, head of state, type of government, most salient cultural norms, and national bird? Unless you happen to be an ornithologist, the national bird might not be a critical piece of knowledge; knowing the basics about a country’s dominant institutions and cultural norms is, however, helpful. In many, especially more senior positions, a deep knowledge base regarding countries and cultures is needed to make well-informed decisions and to respond effectively in cross-cultural contexts.

We all might agree that it would be unrealistic to expect culturally agile professionals to know every sociopolitical issue, religious or cultural norm, legal and regulatory statute that exists in this world. After all, there are nearly two hundred countries on the planet. At the same time, there are some jobs and professions where knowledge about countries and cultures is so critical for success in their jobs that testing candidates and employees on their level of knowledge on these topics is warranted. Diplomats, for example, should be highly knowledgeable in international affairs and how countries and cultures are interconnected. The selection system for U.S. diplomats, not surprisingly, includes a written exam, the Foreign Service Officer Test. This exam assesses, in part, knowledge of global current affairs, regional issues, world history, and geography. Not all global professionals need the same level of knowledge of countries and cultures as diplomats. For some jobs this knowledge might be “nice to have,” but for others, it will be critical.

If you have some critical roles where country and cultural knowledge is essential for success, then knowledge tests can be used to assess candidates and employees. This would be especially important for professionals, like diplomats, whose knowledge would be applied from the first day on the job and cannot be gained over time. This time distinction is relevant for gaining knowledge, given that of all the competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework, knowledge and integration of cross-national and cross-cultural issues will be the easiest for your organization to increase through training. Methods for increasing knowledge in this area will be discussed in Chapter Six.

PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

If you have children, nieces and nephews, or younger siblings, you have probably directly observed the stability of natural personality traits. Perhaps you observed your child as a toddler having such an extreme natural curiosity and sense of fearlessness that you ended up installing industrial-strength baby gates. You might have observed your young nephew’s ease around strangers, melting hearts with his toothless smile, or how content your little sister was to be left alone playing with her toys. Have you noticed how those traits have manifested themselves as your little ones have matured? These stable traits are not unique to the children in your family; all humans have a constellation of stable and relatively immutable personality traits, and they have been found across time, contexts, and cultures.4 Psychologists have nicknamed the five most robust and stable personality characteristics the “Big Five”:

The degree of expression of these five basic personality traits varies from person to person, but the extent to which an individual displays these traits will be relatively constant throughout his or her life.

Personality assessment is important for building a pipeline of cultural agile talent, for three reasons. First, these basic personality traits underlie many of the competencies in the Cultural Agility Competency Framework. Second, these traits have been found to be accelerators for the developmental opportunities your organization offers, such as international assignments. Third, the traits are relatively stable. This means that your employees have certain personality traits when they are hired that are unlikely to change once they are in your organization. In the case of personality traits, selection is critical because the traits directly affect your professionals’ cross-cultural competencies and their abilities to gain them in the future.

Your employees have certain personality traits when they are hired that are unlikely to change once they are in your organization.

Personality Traits Affecting Psychological Ease Cross-Culturally

Two personality characteristics, openness and emotional stability, will predispose your professionals to be more comfortable and well adjusted and to derive greater satisfaction from working in different cultures. Let’s first consider the most intuitively important trait—openness. Individuals with greater openness engage in international experiences and multicultural opportunities because of their natural curiosity. Those higher in openness are receptive to experiencing new and different ways of doing things. When your global professionals are more open, they will generally feel more comfortable with the ambiguity of the cross-cultural context.

Do you recall the days before cars came with satellite navigation systems, when we used an old-fashioned device called a map? If you remember those days, you can probably remember missing an exit or two when driving to unfamiliar destinations. What was your reaction to the missed exit—were you calm and resigned, or nervous and frustrated? The response to this scenario is one sample indicator of your personality (in this case the characteristic of emotional stability). Emotional stability is a basic personality trait that enables individuals to cope with stressors and ambiguities. There is ambiguity associated with working in a cross-cultural context, especially in situations where professionals will be traveling or living internationally. My research, along with the research of my colleagues, has found that emotional stability is particularly important for global professionals’ performance and their psychological comfort working internationally.5

Personality Traits Affecting Cross-Cultural Interactions

When building your pipeline of future global professionals, consider focusing on the personality characteristics that underlie the competencies associated with cross-cultural interactions. Two of the basic personality characteristics, extroversion and agreeableness, predispose people to form relationships, and are especially valuable for global professionals in their relationships with colleagues from different cultures. As we discussed in the previous chapter, relationships enhance professionals’ ability to be more effective cross-culturally.

Let’s first consider extroversion. Many people think of extroverts as the life-of-the party types, when in fact it is more appropriate to think of extroverts as those who enjoy attending the parties and speaking to people while they are there. Extroversion is the tendency to prefer to be with others, as opposed to a tendency to prefer solitude.

Although there are many globally effective introverts, my research has found that professionals who have a higher level of extroversion are comfortable asserting themselves in social settings to form interpersonal relationships with colleagues from different cultures and, as a result, tend to be more likely to effectively learn the social culture when operating in a different cultural context.6 Introverts need to push themselves beyond their natural comfort levels when working cross-culturally. Learning about cultures from peers and colleagues from different cultures is core to the development of cultural agility—making extroversion more important for global professionals.

The same is true when professionals are more affable and collaborative—or agreeable, as it is called in the Big Five list. Don’t we all prefer to spend time with those who are nice, rather than with those who are surly and demanding? Of course we do. Being agreeable should not, however, be thought of as being a pushover. We don’t want global doormats in the organization’s talent pipeline; we want those who are strong professionals and, at the same time, reasonable people who others enjoy being around. My research found that international assignees who are higher in agreeableness report greater cross-cultural adjustment and better performance on the assignment in their host countries. Possessing the combination of extroversion and agreeableness will help your professionals form relationships—a competency that helps them succeed in diverse cultures.

Personality Traits Affecting Decisions in a Cross-Cultural Context

Making effective business decisions in a cross-cultural context requires more effort—they entail greater investigation of a broader range of options, more potential risks, and a higher number of unknowns that need to be understood fully. Cutting corners when working globally usually results in costly mistakes. Your global professionals should have a high level of conscientiousness, which includes perseverance, self-discipline, maturity, and resourcefulness. Wouldn’t you prefer that the global professionals in your organization have the natural tendency to stay committed to their work long enough to explore their options and make the best possible decisions? Immature and less conscientious individuals tend to lack perceptual skills and the cultural sensitivity needed to consider their options. Those who are higher in conscientiousness also tend to be more resourceful. This feature is especially important when your professionals will be working in another country, because often the resources available are quite different from those at home. Not surprisingly, my research found that conscientious global professionals are more likely to be rated as higher performers.7

Testing for Personality Characteristics

Building a pipeline of culturally agile professionals should start with an assessment of the Big Five personality characteristics. These characteristics will accelerate professionals’ development of cross-cultural competencies and help them be effective in a cross-cultural context. Personality assessment will help you assess what your organizations’ professionals “will do” rather than what they “can do” (for example, technical skills and cognitive abilities).8 The Big Five personality traits have also been found to be linked with leader effectiveness, making them important for selecting global professionals in your talent pipeline who will also assume leadership roles.9 The box offers a list of some excellent commercially available personality tests that have shown validity evidence in predicting success among professionals.

INTERVIEW

A world-class executive who displays an enviable level of cultural agility is Andrea Jung, who served as CEO of Avon Products from 1999 to 2012, when she stepped down but remained with the company as chairman of the executive board. She is a first-generation Chinese American who grew up balancing Chinese and North American cultures. “My parents kept the best aspects of the Asian culture, and they Americanized the family,” Andrea said in an interview for the online newspaper GoldSea. By the time she finished high school, Andrea had studied Mandarin, Cantonese, and French. She was accepted at Princeton and graduated magna cum laude with a degree in English literature, planning to become a lawyer. At this point, however, she ran into a cultural barrier of a different sort. Before applying to law school, she accepted a position with the Bloomingdale’s department store chain, planning to spend two years gaining a thicker skin and firsthand knowledge of how business is done in the real world.

Her academically inclined parents (her father was an MIT architecture professor and her mother a concert pianist who had previously achieved recognition as a chemical engineer) were aghast. When Andrea decided to pursue a career in retail over the long term, according to a GoldSea article, they “complain[ed] bitterly that she was dumping all they had invested in their little girl into the waste heap and lowering herself into the same class as street hawkers and used car salesmen.”10 Working in retail sales was simply not acceptable as an appropriate career option in the culture in which Andrea had been raised. Her goal of becoming less thin-skinned had to be fulfilled in more ways than one: she learned not only to hold her own in the pushy world of retail but also to disagree with her parents without alienating them.

As she worked her way up the corporate ladder, she was challenged by another cultural divide. Although women do most of the shopping in high-end department stores, the executives in these corporations are predominantly male. Being a woman in top management meant working in a male-oriented corporate culture where the one who was louder, stronger, and faster was the winner. It took discernment to seek out successful, supportive female role models and to initiate campaigns to give female customers the products and the store ambience they truly wanted. Tuning in to women’s desires became even more critical when Andrea joined Avon in 1993. The century-old cosmetics company badly needed a new, more up-to-date image. To reshape Avon in popular culture and attract younger women, Andrea launched the Just Another Avon Lady and Olympic Woman campaigns, which tied in to the 1996 Olympic Games and featured such athletes as Jackie Joyner-Kersee and Becky Dyroen-Lancer.

Avon’s global reach gave Andrea the opportunity to come full circle with her childhood lessons in Mandarin. In her first year as CEO, she traveled to twenty countries, including China, where she addressed Avon employees in their own language. “I know that women today are far more alike than not,” she told Harper’s Bazaar. “Consider the business opportunities that we’re giving women in China, and then they see a Chinese American at the top. It’s not so much about me; it’s more that these women see that it’s possible.”11

Andrea’s experiences, both personal and professional, have shaped her cultural agility. Her biography includes many examples of times when she effectively overcame cultural differences, behaved in a countercultural way when the occasion called for it, used her language and cultural skills to adapt, integrated bicultural perspectives—the list continues impressively. If you were interviewing her for a position in your organization, you would quickly see the pattern of evidence of her cross-cultural competencies.

Not all candidates will have such an impressive repertoire of experiences from which to draw, but it is helpful to conduct interviews as part of the talent management approach for developing cultural agility in your organization’s workforce. Interviewing candidates is the most comprehensive way to assess their cultural agility—but it is also the most time consuming. In an interview, you can go deeper than surface-level experiences to determine whether the candidate or employee is truly culturally agile. As we have discussed, it is possible for individuals to, for example, live in another country but not have any connection with the culture by staying mostly within their expatriate communities or by befriending compatriots. The interview gives you a chance to assess not just what they’ve done but also their reactions, preferences, motivations, and results.

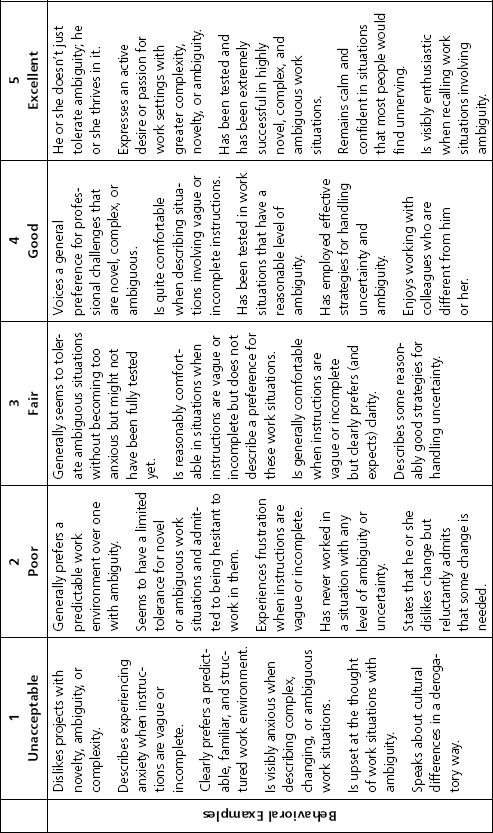

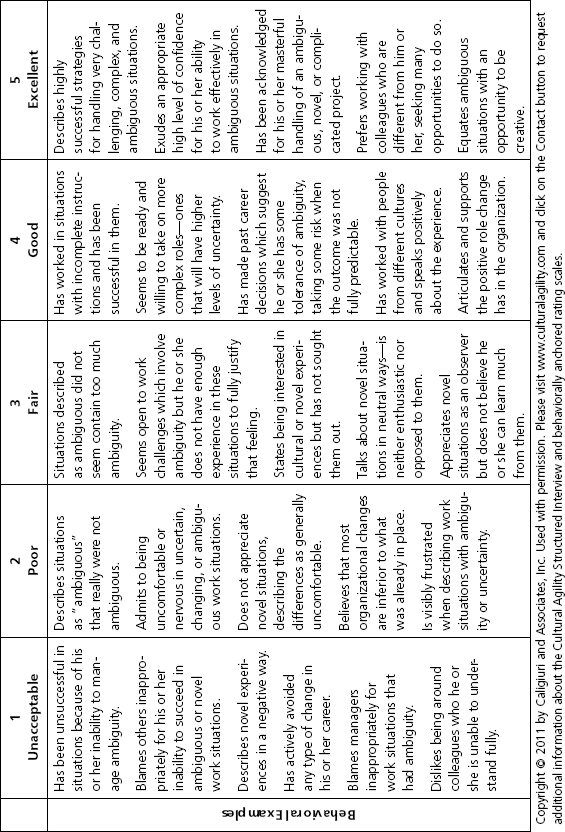

I’ve provided a sample excerpt from my Cultural Agility Interview and scoring guide. (You can contact me at www.culturalagility.com for more information about the full Cultural Agility Interview and scoring guide.) The sample includes the behaviorally anchored rating scales (BARS) associated with one of the twelve cross-cultural competencies, cultural minimization. BARS will enable those who are conducting the interview to standardize their ratings and focus on the interviewee’s behaviors rather than on the rater’s impressions of the person. When reading through the BARS for this sample dimension, please keep in mind that the points on the BARS are examples of the responses you might hear in interviewees’ responses. They are not a checklist for what you should hear or a comprehensive guide to what you will hear.

Sample Behaviorally Anchored Rating Scale for the Tolerance of Ambiguity Dimension of the Cultural Agility Structured Interview

When training your hiring managers in the use of the Cultural Agility Interview, you should mention two rating errors assessors frequently make that are unique to cultural agility. One error is to assume that someone who appears to come from a multicultural background is, necessarily, culturally agile. The opposite assumption is likely to be equally erroneous: that someone from a majority group would necessarily be devoid of cultural agility. Do not prejudge or assume cross-cultural competence (or the lack of it) from overt appearances or accents. Assess it. Another error is to be self-referential when judging others’ interview responses. Hiring managers must try not to hold up their own life experiences as the standard against which to judge others. There are many ways these cross-cultural competencies might manifest themselves. Managers need to allow the candidate to share her own story, and judge her level of cross-cultural competency on her response, not on the manager’s impression of the candidate’s experiences themselves. For example, some people who have traveled very little in their lives can exhibit tremendous cultural agility.

SELF-ASSESSMENT

We believe it was Socrates who gave us the sage advice approximately twenty-five hundred years ago to “know thyself.” This is especially great advice for your organization’s associates who think they might be interested in careers requiring cultural agility. Self-assessment is different from all the other assessments discussed in this chapter. Self-assessment is self-discovery, not evaluation. It gives candidates or employees an opportunity to consider their strengths and weaknesses relative to what it will take to live comfortably and work successfully in another country or with people from diverse cultures. As will be discussed more in Chapter Eight, self-assessment is often used by companies to help professionals make a decision regarding whether an international assignment is really right for them.

You don’t need to be sending people on international assignments to use a self-assessment tool. Including self-assessment for cultural agility at the start of your selection system is a relatively low-risk, low-cost, and high-return tool. These assessments are private and confidential. The scores and interpretations found in the tool are for self-awareness and allow for a self-nomination to the next step of your selection system. In truth, these self-assessment tools weed out very few people (only about 2 percent), but they have some added benefits:

- They build self-awareness and appropriate self-efficacy when your candidates and employees discover that they have what it takes to potentially be successful as a global professional.

- They point out developmental opportunities without risk, given that they are private and confidential.

Self-assessment tools are not foolproof. If you’ve ever listened to karaoke, you have probably heard people who have an overly inflated perception of their strengths. It is human nature to overestimate one’s strengths, and as a result, not everyone will internalize self-awareness data accurately. At the opposite extreme, however, some people underestimate their strengths, refusing to believe that they possess the raw talent that others see in them. Given that global success often requires a fair dose of humility, the underestimation end of this continuum concerns me less. Low self-efficacy for international work can often be enhanced appropriately when presenting clear evaluations of what it takes to be successful, a feature of most self-assessment tools. In any case, though, internalized accuracy in regard to personal strengths is needed.

Those who take self-assessments will often want to know how to improve their competencies. This piece is very important, as self-awareness should be followed by self-development for those who want to build a global career. As we will discuss in the next few chapters, some cross-cultural competencies are easier to change than others. (For example, gaining knowledge about another country’s legal system is easier than building a tolerance for ambiguity.) Your self-assessment tools should consider the level of mutability of cross-cultural competencies when offering feedback on developmental opportunities. I encourage you to explore the Cultural Agility Self-Assessment (CASA) as one option for self-assessment. (Chapter Nine includes more information and provides access to a single-use trial of the CASA.)

There are clear indicators to help identify culturally agile professionals who will be, from day one, effective in cross-cultural or international settings. Although many more individuals might be able to gain cultural agility over time, your organization no doubt has some critical roles for which there will be no time to ramp up, no time to develop talent into culturally agile professionals. Consider using the Cultural Agility Selection System to identify those who possess cultural agility and those who will continue to develop their cultural agility.

It is important to remember that in assessing for cultural agility, you are identifying those professionals who will succeed in the cross-cultural job context. This means that you are predicting success in the context of the job, not the content of the job. However, I’m not suggesting that you ignore the content for the sake of the context; technical skills are also necessary for success. Sending a culturally agile professional to do a job that requires engineering skills will not result in success unless the professional does, in fact, possess the necessary engineering skills. It helps to think of the Cultural Agility Selection System as a piece in a sequential process; this selection system helps build a pipeline of professionals who can be effective in cross-cultural contexts. From that full pipeline, your organization should be able to effectively assign professionals to roles on the basis of their technical skills.

TAKE ACTION

Based on the information presented in Chapter Five, the following is a list of specific actions you can take to begin implementing strategies to assess and select for cultural agility in your organization.

- Tailor your approach for résumé screening. Using the tips offered in this chapter, your applicant tracking system and recruiters can more effectively screen for candidates who will likely possess or be able to gain cultural agility.

- Test for foreign languages, knowledge, and personality traits. If you plan to use the tests recommended in this chapter, base your test selections on the cultural agility job analysis. You can conduct a validity study under the guidance of HR professionals or industrial and organizational psychologists who are specifically trained in the technical aspects of test validation. As with all employment testing, it is important to ensure that the tests you are using meet accepted standards of reliability and validity. Your selection system should be adapted for your organizational context and for key jobs, job families, functional areas, and business units.

- Use a structured interview. A sample of the Cultural Agility Interview protocol is offered in this chapter. For more information about the entire Cultural Agility Interview protocol, please visit www.culturalagility.com.

- Offer a self-assessment tool, such as the Cultural Agility Self-Assessment (CASA), to anyone who might enter your talent pipeline of global professionals. The CASA can also give job candidates a way to structure and think about their cross-cultural competencies and understand the importance of cultural agility in your organization.

Notes

1. TalentDrive, “Annual Labor Market Survey Finds Rise in Companies Planning to Increase Recruitment Spend in 2011,” January 27, 2011, http://www.amerisurv.com/content/view/8300/2/.

2. Zofia Wodniecka and others, “Does Bilingualism Help Memory? Competing Effects of Verbal Ability and Executive Control,” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13, no. 5 (2010): 575–595; Ellen Bialystok, “Cognitive Effects of Bilingualism: How Linguistic Experience Leads to Cognitive Change,” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10, no. 3 (2007): 210–223.

3. Ellen Bialystok and Dana Shapero, “Ambiguous Benefits: The Effect of Bilingualism on Reversing Ambiguous Figures,” Developmental Science 8, no. 6 (2005): 595–604.

4. Numerous scholars have written on the Five Factor model of personality. See, for example, Paul Costa and Robert McCrae, “Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory,” Psychological Assessment 4, no. 1 (1992): 5–13; Robert McCrae and Paul Costa, “More Reasons to Adopt the Five-Factor Model,” American Psychologist 44, no. 2 (1989): 451–452; Robert McCrae and Paul Costa, “Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52, no. 1 (1978): 81–90; Robert McCrae and Oliver John, “An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and Its Applications,” Journal of Personality 60, no. 2 (1992): 175–216.

5. Paula M. Caligiuri, “The Big Five Personality Characteristics as Predictors of Expatriate Success,” Personnel Psychology 53, no. 1 (2000): 67–88; Paula M. Caligiuri, Ibraiz Tarique, and Rick Jacobs, “Selection for International Assignments,” Human Resource Management Review 19, no. 3 (2009): 251–262; Stefan T. Mol and others, “Predicting Expatriate Job Performance for Selection Purposes: A Quantitative Review,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 36, no. 5 (2005): 590–620.

6. Paula M. Caligiuri, “Selecting Expatriates for Personality Characteristics: A Moderating Effect of Personality on the Relationship Between Host National Contact and Cross-Cultural Adjustment,” Management International Review 40, no. 1 (2000): 61–80.

7. Caligiuri, “Big Five Personality Characteristics.”

8. Timothy Judge and Remus Ilies, “Relationship of Personality to Performance Motivation: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, no. 4 (2002): 797–807.

9. Robert Hogan, Gordon J. Curphy, and Joyce Hogan, “What We Know About Leadership: Effectiveness and Personality,” American Psychologist 49, no. 6 (1994): 493–504; Timothy Judge and others, “Personality and Leadership: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review,” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, no. 4 (2002): 765–780.

10. “Executive Sweet,” Goldsea: Asian American Wonder Women, n.d., http://www.goldsea.com/WW/Jungandrea/jungandrea.html.

11. “Andrea Jung,” Encyclopedia of Business, 2nd ed., Reference for Business, http://www.referenceforbusiness.com/businesses/A-F/Jung-Andrea.html.