Prevention of Crime in and Around High Schools

Lessons in Implementation and Dissemination*

Paul van Soomeren CEO, DSP-groep (http://www.dsp-groep.eu/)

CEO, DSP-groep director of the board, the International CPTED Association and the European Designing Out Crime Association

Sjoerd Boersma Senior advisor and partner, DSP-groep, and co-owner of IRIS

Abstract

This chapter outlines the Safe and Secure Schools matrix and explains the five stages of developing an integrated policy for school safety and security. The research on and development of school security policies in Amsterdam and throughout the Netherlands is used as an example of how plans are created.

The Safe and Secure Schools (3S) Matrix: How Mature Is a Safety and Security Policy?

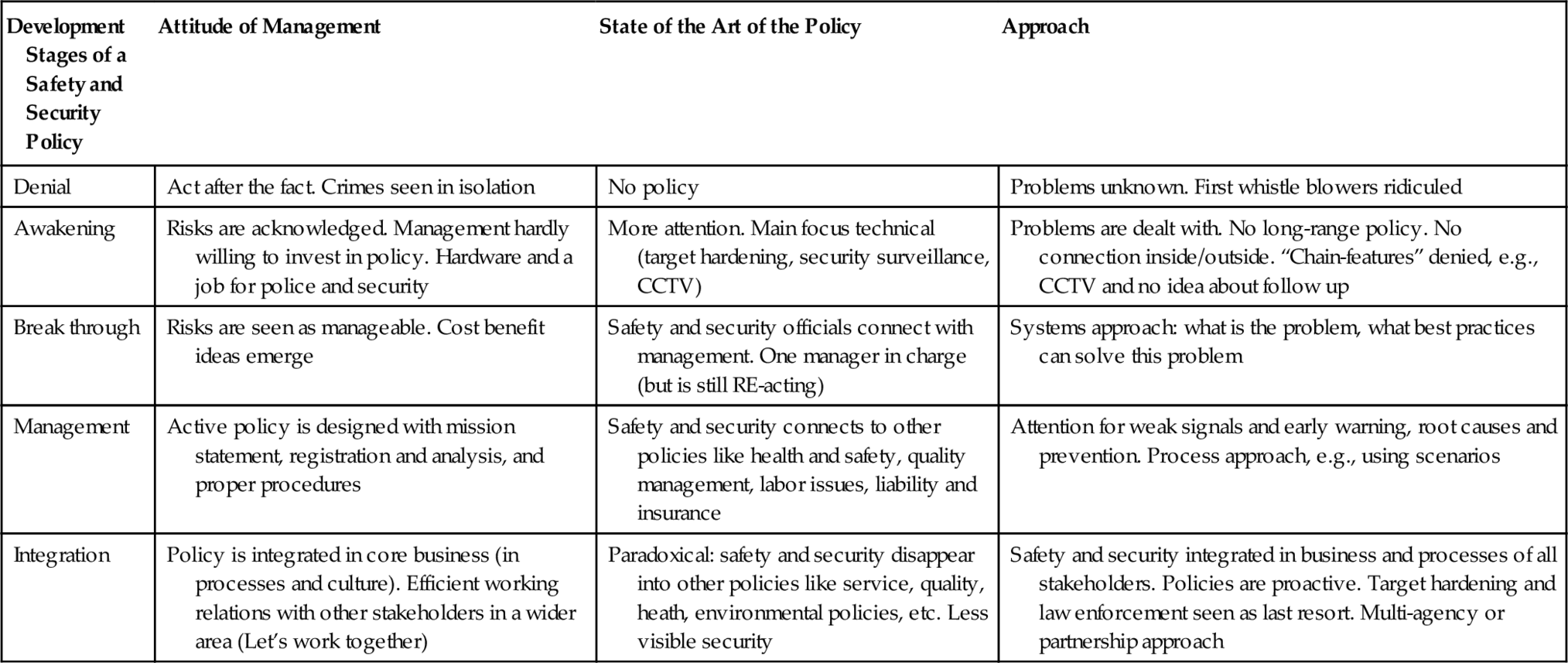

Based on ideas about implementing quality management,1 a group of Dutch crime prevention experts2 have designed a Safe and Secure Schools (3S) maturity matrix (also based on Crosby 1991). The matrix, seen in Table 25.1, presents the five stages that unfold over the course of developing a foundation for an integrated policy for safety and security: denial, awakening, breakthrough, management, and integration.

Table 25.1

Safety and Security Stages Matrix

| Development Stages of a Safety and Security Policy | Attitude of Management | State of the Art of the Policy | Approach |

| Denial | Act after the fact. Crimes seen in isolation | No policy | Problems unknown. First whistle blowers ridiculed |

| Awakening | Risks are acknowledged. Management hardly willing to invest in policy. Hardware and a job for police and security | More attention. Main focus technical (target hardening, security surveillance, CCTV) | Problems are dealt with. No long-range policy. No connection inside/outside. “Chain-features” denied, e.g., CCTV and no idea about follow up |

| Break through | Risks are seen as manageable. Cost benefit ideas emerge | Safety and security officials connect with management. One manager in charge (but is still RE-acting) | Systems approach: what is the problem, what best practices can solve this problem |

| Management | Active policy is designed with mission statement, registration and analysis, and proper procedures | Safety and security connects to other policies like health and safety, quality management, labor issues, liability and insurance | Attention for weak signals and early warning, root causes and prevention. Process approach, e.g., using scenarios |

| Integration | Policy is integrated in core business (in processes and culture). Efficient working relations with other stakeholders in a wider area (Let’s work together) | Paradoxical: safety and security disappear into other policies like service, quality, heath, environmental policies, etc. Less visible security | Safety and security integrated in business and processes of all stakeholders. Policies are proactive. Target hardening and law enforcement seen as last resort. Multi-agency or partnership approach |

Our story starts in the Netherlands (17 million inhabitants) in the 1980s. This was during a period (1970-2000) in which the Netherlands experienced a rather extreme rise in a number of crimes like theft, burglary, arson, vandalism, and violent crimes. By that time, Amsterdam (1 million inhabitants)—the capital city with a young and very diverse population—ranked first in the fast rising national crime statistics. In any population, most offenders and victims can be found in the age group of 10-253 years; therefore, schools in Amsterdam are obviously at a triple crime risk: the Netherlands ranking high in crime statistics, Amsterdam ranking highest within the Netherlands, and high schools with adolescents aged 12-18 the riskiest. Furthermore, research in the 1990s showed risks at the workplace to be twice as high as the crime risks in public spaces.4 The jobs having the most contact with the public have the highest risks: public transportation, schools/education, shops, and hospitals/health care.5 The workplace risk in these professions is about 4-10 times higher compared to the overall population.

In that era, schools in Amsterdam were thus the top target for crime prevention. But for years not much happened and schools stumbled along without assistance. No one dared to mention problems of crime, insecurity, and incivilities, afraid that their schools would suffer a market loss because of a wrecked image, along with pupils and staff leaving.

Why did it take that long to start a sophisticated crime prevention initiative for schools? The answer is shown in the matrix in Table 25.1. It takes a while to adjust to higher crime levels and build a sound foundation for a mature and integrated safety and security policy. Schools are no different in that respect and, in facing higher crime trends, the schools also went through the stages of denial, awakening, breakthrough, management, and integration.

Denial

Seeing the general crime trends in the Netherlands, it is difficult to explain why not only schools in Amsterdam but also police, neighborhood residents, health and safety officials, and public transportation officials defined crime and insecurity as a problem they had to deal with by themselves for so long. Until the beginning of the 1990s, the development stage in schools was still mostly the denial mode. At best, the problems with crime and insecurity were defined as vandalism problems: youngsters purposefully demolishing public objects, breaking a few windows, and playing a bit too rowdily. An approach to these vandalism problems had already been developed more than a decade before, and schools could participate in the approach if they wished to do so.6 This antivandalism policy had more or less faded away by the end of the 1980s due to changes in personnel and thus the antivandalism policy simply evaporated.

Awakening

Of course, the shift from denial to awakening was helped by factual information about the crime and insecurity situation in the Netherlands, in Amsterdam, and in the schools.7 However, most of this knowledge was already publicly available for years, but it lay dormant. The awakening for schools in Amsterdam was actively helped by a push from the health and safety officials from the city of Amsterdam who simply followed new regulations issued by the National Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. These regulations—which were part of the Health and Safety Act since 1995—forced employers to take precautionary measures against aggression, violence, and sexual intimidation in the workplace. Two groups of officials from the city of Amsterdam now realized they were more or less pursuing the same cause:

• On the one side, the health and safety officials and

• On the other side, a newly appointed, but very experienced, project coordinator for school security.

Health and safety officials looked only at the staff (teachers, management, administrators, technical staff/facility management in schools). The project coordinator for school security was mainly driven by his or her task to help implement a new citywide policy aimed at youth (in general) and safety in Amsterdam. Within this broader policy, there was also substantial funding available for a big school project. The officials of the city of Amsterdam (health/safety as well as school security officials) asked a group of private and public experts to help formulate a policy. This public-private partnership—a rather unique construction—joined under the name Amsterdam Partnership for Safety and Security on Schools. The first task of this partnership was to start diagnostic research in all high schools: schools with pupils in the age range of 12-18 years, where on average each school has a population of between 1000 and 2000 students.

Breakthrough: Research Showing the Risks, Victims, Offenders, and Incidents

The diagnostic research8 started as a pilot for a group of four schools and was then held in the eastern region of Amsterdam (1997), then the western region was added (1998), and later on (1998/1999) the southern school region of Amsterdam was added. This step-by-step approach reflects the necessary efforts to gain the participation of the schools as well as the methodological difficulties in combining separate research traditions. In fact, this research established for the first time a structural liaison between schools within one region concerning crime and insecurity issues. Another unique feature of this research was that it succeeded in combining several types of diagnostic research:

• A general questionnaire for staff and personnel following the standard model of a risk assessment questionnaire on health and safety (as obliged by the Health and Safety Act mentioned earlier).

• A victim survey/ questionnaire for pupils and staff using the model for standard Crime Victims Survey.9

• A self-report questionnaire asking pupils to indicate what incidents they committed or witnessed in and around their school; the standard Dutch national youth and crime self-report study was used as a basis here.10

Integrating these different types of research, each having its own traditions and background, proved to be a difficult job which only succeeded because the research was a combined effort of health and safety researchers in Amsterdam and researchers specialized in victim and self-report crime research (DSP). What was born here was the idea of an integrated survey/monitor that included a victim survey as well as a self-report survey, for both pupils and staff. The survey we developed during this period (or monitor as we called it later on) became part of a complete web-based tool to monitor school safety called Incident Registration in School (IRIS) and is used by schools to register incidents, do surveys among pupils and staff, and include factual reviews of crimes and incivilities (e.g., arson, a broken window, graffiti) by using an app. All this information can be shown on a uniform dashboard in each school; but since all IRIS input is anonymously stored in one national database, easy benchmarking with other schools is also possible.

Victimization (staff and pupils), incidents, and seriousness of offenses/offenders

The number of incidents reported in the survey (shown in Table 25.2) astonished everyone; not only the number of incidents reported by victims (staff and pupils) but also the number of incidents reported by the offending pupils themselves. In addition, the fact that about 40% of all incidents were considered serious incidents convinced people that action had to be taken. The research showed that schools only had knowledge of about 15% of all incidents. For the police, this figure was about 1%. Pupils themselves knew about far more incidents compared to the school and the police, and of course pupils talk about these incidents with one another.

Table 25.2

Number of Incidents (Staff/Pupils) per Year as Reported by Victims and Self-reported by Offending Pupils12

| Total: 39 Schools Period: 1997-1999 | |

| Pupils | |

| Number of pupils | 19,236 |

| Number of incidents from victim survey | 155,000 |

| Number of incidents self-reported | 244,000 |

| Number of self-reported incidents considered serious | 94,000 |

| % of self-reported incidents known to school | 15% |

| % of self-reported incidents known to police | 1% |

| Staff | |

| Number of staff | 2212 |

| Number of incidents from victim survey | 13,000 |

Response rate for staff was 50-70%, and for pupils was 80-90%. Incidents included aggression/violence, burglary, sexual intimidation, arson, vandalism/graffiti/demolishing objects, theft, and nuisance (bullying, conflicts). Seriousness ranking: see Steinmetz (2001).13

Note: the first pilot research in four schools (3400 pupils/470 staff) is excluded from the table because results are difficult to compare.

The research also showed that young pupils committed more crimes than older pupils. This result is similar to the result of research done in primary schools in Amsterdam (pupils aged 4-12 years). According to that research, children start committing incidents/crimes at the age of 10.11 Boys report they commit more such incidents than girls, and boys are also more often a victim of such incidents. The research also showed some important regional differences. From the perspective of crime victimization studies, self-report research, and risk assessment studies, these results were not extremely surprising: On a global scale, the Netherlands ranks high on the crime charts, Amsterdam ranks high within that country, and schools (youth/workplace contacts) are a risky part of society.

However, the schools reacted in a surprised or shocked manner and were angry sometimes. Evidently, this thorough research brought most schools to the development stage of Breakthrough as mentioned in the 3S maturity matrix presented above. Schools—as well as other institutions like local authorities, police, and so forth—started to ask themselves questions like “How come there are so many and such serious incidents?” “What can be done about this?” and “Why shouldn’t we work together to combat crime and insecurity?”14

There was one more important outcome of the research. Everyone realized that structural registration and research was important to monitor the development of safety and security in schools. Hence, the research was also the starting point of a project to register incidents, not only for high schools but also for primary schools and professional education institutes in Amsterdam. Registration of incidents by schools themselves was an essential component. To be able to compare results and analyze these data, they were stored in a CD-ROM that made it possible to register incidents in a uniform way. The result was the start of the tool IRIS. The CD-ROM was distributed to all schools in Amsterdam by a researcher who traveled to all schools every few months to collect the data. This registration tool became an instant success; later on it became web based and was used in more and more schools in the Netherlands.

Start of the Management Stage: Six Types of Focus Groups

Focus groups were created, consisting mainly of staff and pupils from the schools. However, the CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design) group also included police, public transport authorities, civil servants, local authorities, and maintenance officials. The aim of the focus groups was for schools to interpret together the research results for their region and formulate counter and preventive measures in six fields:

1. School building, surroundings, neighborhood, and travel from/to school (this focus group mainly looked into CPTED issues);

2. Rules and enforcement/sanctions;

3. Victim support and follow-up care;

4. Mediation, complaints policies, coaching, and school counselors;

5. School climate and training of staff and pupils to discuss and handle crime and insecurity;

6. Policy plans, implementation, and registration/monitor systems.

Each focus group had to come forward with measures, ideas, schemes, and initiatives and then rank all those ideas in a priority scheme. As an example, we will concentrate on the work done by two of these focus groups: the one on CPTED and the one on registration/monitor systems.

CPTED focus group

The research summarized above had already shown the importance of looking at the routes from and to school and the school neighborhood and surroundings. Not only were the routes from and to school and the school neighborhood perceived as more unsafe and insecure than the school premises and the school building itself by the pupils but also the real crime or incident risk was high. The perception of crime and insecurity problems outside the school were sadly proven true by an incident that happened around this time: Several schools in Amsterdam-West are located next to a line of the light rail public transport system. There were frequent rows and fights between pupils at the roads to the station and on the platform. One day, two girls were fighting on the platform and one of them pushed the other onto the rail, where she was killed by the approaching train.

This case sadly showed several things: a strict division between inside school and outside school is not a very helpful distinction for incidents because problems and conflicts often start inside and explode once outside or the other way around. This case also showed the difficult intermingling of problems and solutions and the number of participants involved. For instance, possible solutions were to prevent fights, take quick action when fights are seen or reported (the station was equipped with closed-circuit television, CCTV, but no one monitored the images), change school hours and thus prevent students of different schools from clashing into each other while leaving school, have more tram carriage capacity available on peak hours, crowd control, and educating pupils about risks and about quick intervention tactics.

Within each regional CPTED focus group, the schools learned a lot from the practices and experiences of each other. Schools, together with officials from police, public transport, local authorities, and city management, were able to formulate a set of new and comprehensive measures in the fields of public transport, neighborhood maintenance, fire prevention and evacuation, and multiagency cooperation. Some of these measures were so simple that they could be implemented instantaneously while other plans—such as architecture and urban planning—needed more time. Also, a new way of analyzing problems emerged: mixed groups of stakeholders (pupils, teachers, police, staff, etc.) simply walked in and around the school premises to make an inventory of problems they perceived. This was later elaborated upon in a structured method for risk assessment: a review. This so-called review emerged where individuals or groups walking around—in sun and rain, light and darkness—made notes and took photographs, resulting in prestructured risk/solution assessment reports. Years later (2009), this prestructured method for risk assessment was integrated with IRIS. This review—nowadays everyone uses the IRIS review app (see Figure 25.1)—enables schools to register incidents (e.g., a broken window), mark and photograph hot spots, and assess security risks.

Another thing the CPTED focus groups found out while identifying measures already taken was that most schools were already very active in the field of combating crime and insecurity. However, most security measures are not really incorporated into sophisticated policy plans. There is no connection between the research outcomes and analysis of the problem and the goals/plans and the measures. There is much action, but often the wrong action. For instance, the biggest problem for pupils is the unsafe and insecure situation in the school neighborhood and the routes from and to school, but schools had hardly implemented any measures aimed at this problem and did not invest in cooperation with those who might be able to change this situation. There was also a profound lack of systematic evaluation of measures already implemented. In short, there is a lot of action but it is questionable how effective and efficient this action is.

Registration and monitoring

The same problem could be seen by the registration policies; schools did put effort into the registration of incidents, but it was done in a rather clumsy way (e.g., by the registration of incidents in the personal files of pupils). This way there is never a systematic and statistical sound overview available because the registration is completely personalized; there is no central place to compile the information. From the beginning of the 1990s, it was clear that not much was known about the actual crime situation and/or the risks in a school as long as there was no (uniformity in) registration. In one of the focus groups, the layout of a sound system for IRIS was developed step by step. Altogether, this process took about 10 years. This digital tool was distributed on a CD-ROM to all schools in Amsterdam and from there it was copied by schools nationwide. The first real investigation into incidents in Amsterdam was started by a researcher on a bicycle who visited all schools and tried to get the data that were registered on a stand-alone computer somewhere in a school. There was a uniformity in registering incidents, but it was hard to gather the information.

The CD-ROM spread through the Netherlands, and schools in other cities (Rotterdam and Haarlem) started to use it as well. By this point, schools wanted to access the tool on the Internet and thus have easier accessibility and better and easier benchmarking possibilities, though in the beginning privacy issues scared some schools. IRIS developed into a web-based tool in 2004. First, a school must know basic facts about what the problems with crime and incivilities are (what, where, when, who), but an even more important next step is to know what to do to tackle and prevent these problems. Hence, a standardized method on how to organize school safety, one for which a school could get an official national certificate, had to be developed. It was based on the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) control cycle, where schools decide for themselves what their goals are and how they are going to reach these goals. This PDCA (or adjust) cycle is an iterative four-step management method used in business for the control and continuous improvement of processes and products. It is also known as the Deming circle/cycle/wheel and it forms the basis for a lot of international standards for quality management (e.g., ISO 9000 series) and crime prevention (e.g., the European standards of the CEN 14383 series).15 The standardized method for safe and secure schools was developed with the Dutch Ministries of Interior and Justice.

This standardized method16 starts with a step in which a school has to do a thorough analysis of the crime and safety situation, preferably not only in and around the school but also in the wider neighborhood. As we have seen above, this was not that easy a task. In Amsterdam only, 15 years ago, we had to do long and difficult victim surveys that lead to a breakthrough for action to tackle and prevent crime. But nowadays, this difficult and costly research is no longer needed. Every incident that a schools feeds into the registration tool IRIS—and the info from school surveys/monitors and factual reviews as well—is stored (anonymously) in a central database (see Figure 25.2). Hence, every school using the IRIS tool can not only research and analyze its own crime and safety situation but can also compare and benchmark their situation with other schools (e.g., of the same type). An interesting side effect of using this crime and safety registration/survey/review tool was that the terminology of the problems with crime and incivilities (for example) were standardized (the “what is the problem” question), but also the indications of places (where, hotspots), time, and types of offenders and victims was more standardized. The IRIS tool was used for a while as a stand-alone software package, but later on it was completely integrated in the regular administrative school software which is sold by the main administrative software companies in the Netherlands. The same incident can now be seen in the personal file of a student and it can be used to make a complete safety analysis. Nowadays, the IRIS system is used in 30% of all the Dutch high schools, 20% of the primary schools, and 20% of the professional education sites.

Conclusion

Thinking back to the scheme which introduced the Safety and Security Stages matrix (3S), we have seen the Amsterdam School Safety and Security initiative slowly reach the stage of management: an active safety and security policy had emerged between the end of the 1990s and 2005. By then, everyone was convinced that an integrated multiagency approach was really necessary. There were safety and security coordinators appointed within each school. A real policy was formulated not only within the school but also for the different school regions and Amsterdam as a whole. CPTED was an integrated and important part of this policy. It took all participants about 5 years to come from the stage of denying crime and insecurity problems in and around schools to the stage of a more integrated approach.

Unfortunately, in Amsterdam, this whole machinery still proved to be considerably weak. In 2009, the city of Amsterdam decided to stop funding this policy, so schools had to take care of their own security and safety, including the exchanges between schools as well as between schools and the local authorities. Schools were assumed to have reached the final stage in the security matrix by that time. Within a few years, it showed that schools were not willing to pay for the integrative machinery by themselves. Obviously, the last stage in the maturity matrix—integration—had not yet been completely implemented in Amsterdam. This may come as no surprise since the term multiagency approach is easily tossed around, but the implementation of a sophisticated multiagency approach is not light a task17 and it showed to be a heavy burden in the Amsterdam school safety and security policy too. From then on, it was mostly once again each school working on its own. With no integration (stage 5), the machine was stuck in stage 4 (management). However, a lot was learned by then. There was knowledge about crime prevention and CPTED18 and most schools had a better and more realistic focus on safety and security. Full integration of the safety and security policies in all schools in a city of 1 million inhabitants was obviously a bridge too far. Amsterdam and the high schools in Amsterdam settled for the management stage.

What did blossom most of all was the digital registration, review, and the survey tool IRIS. This tool started out in Amsterdam, but was used all over the Netherlands within a couple of years and not just in high schools but also in all types of schools in the country. Essential in a 3S Safe & Secure School policy is a program that includes social safety, environmental safety, and organization around safety. School management needs to develop safety policies based on facts. To feed a school—from management down to every classroom—with information on safety and security, factual information and data have to be collected and processed. IRIS proved to be an easy solution for this. In the end, the system was collectively used through the full integration in the administrative school software, enabling an evidence— or at least fact—based school safety approach to tackle and prevent crime in an individual school using the information of other schools to benchmark and compare. Hence, while most schools nowadays are in the management stage of the 3S maturity matrix, the crime registration and analyses has reached full integration.