12

Creating Multidimensional Characters

“A Story”

Once upon a time in a certain place there lived a being who had both strengths and a flaw. This being wanted to achieve a goal. However, there was an obstacle between the being and its goal of such a nature that it attacked the being at its weakest point–its flaw. The being realized that, to achieve its goal, it must overcome the obstacle.

The being struggled to remove the obstacle, trying first one thing, then the next; each time failing–the goal remaining just out of reach. The being at last designed a plan that would make its weakness invulnerable to the obstacle and would, at the same time, achieve its goal.

The plan failed; the being realized its weakness could not be made invulnerable.

The being put on one last, desperate effort to overcome its weakness, and by so doing, the being overcame the obstacle and achieved its goal.

The End.

(From A Science Fiction Writer’s Workshop-I:

An Introduction to Fiction Mechanics by Barry Longyear)

This simple story plan goes a bit beyond Bill Idelson’s definition of story. It states that an important element in a story is that the main character has a flaw that makes the hero particularly vulnerable to the obstacle. The story then involves finding ways to get rid of the weakness and overcome the obstacle.

That definition of story can be of great value in simulation design. In serious games it is not enough that a hero is overcoming an obstacle. The hero has to deal with a personal deficiency. How do people deal with personal performance deficiencies? Well, certainly one very good way is through training!

Stories allow people who take on the role of hero to discover their own deficiencies and learn how to overcome them. As Longyear suggests, the deficiency can never fully be overcome, so the hero has to use a combination of skills to overcome the obstacle despite of the deficiency.

In serious games, giving heroes the skills to overcome their deficiencies is the behavioral objective of the exercise. If the goal of the exercise is to teach the participants how to make decisions under stress, then the participants selected to go through the exercise are those who have performance deficiencies in that area. The obstacle is created especially to challenge those kinds of deficiencies. In the end the hero gets better at making decisions under stress until, at the climactic moment of the story when the hero must make the most critical decision at the moment of highest stress imaginable, he or she will be able to reach the goal by integrating a number of additional skills.

If the system is smart enough, as ALTSIM intended to be, it would read the performance of the hero and tailor the obstacle to match the hero skill for skill, to challenge strengths and take advantages of weaknesses. A leader who is clear thinking enough to get a strong troop movement toward the town of Celic to rescue a trapped inspection team might suddenly have the ALTSIM system itself add elements to the obstacle to make the job even tougher.

Part of the function of an interactive simulation is to help the participants (heroes) discover their own flaws and figure out how to overcome them. Then the system must keep challenging those flaws to help the heroes minimize them. In the meantime, the participants actually become the heroes and are personally engaged in the struggle. As Bill Idelson would say, the juices flow.

NONPLAYER CHARACTERS (NPCs)

Captain Moran (the former leader of the food distribution mission in Afghanistan, the one who the participants were to replace in the Leaders simulation) was a real presence, though he was never seen. Like so many leaders who are gone but not forgotten, his looming authority and methods added an element of challenge and realism to the experience. Other NPCs were present and served as the principle mechanism for presenting information to the participant/hero and asking for decisions. Again, their perceptions and opinions would color the participants’ view of the world.

Two of the most important characters in the Leaders project were First Sergeant Jones and the company Executive Officer (XO) Ricardo Perez. We chose to give these two characters especially rich backgrounds, and as a result they became complex challenges for the new Captain. For example, we gave Perez personal ambitions of command so that he did not really want to cooperate with the new Captain. He would always want to do things himself, he would give information grudgingly and, during one of the earliest encounters in the simulation, he would actually try to convince the Captain to turn the entire operation over to him. His reasoning was that a new Captain should not just come in and take over an established plan that had already been well worked out. He should leave the plan to the XO who was already well versed in it. Perez’s goal was to run the operation himself. We created the character and the situation in order to allow the participants to encounter one of the most important teaching points in the simulation, the need for the leader to establish control and credibility immediately upon assignment to a new unit. The following is a bit of dialog from that section of the simulation. (Developed by Paramount for the ICT.)

LOOKING OUT OVER SITE–PEREZ PITCH

Perez stays in the frame, but we should be able to see much of what’s going on on the site floor.

PEREZ

Captain Moran, Top and I reconned the site yesterday morning! Made risk assessments and laid out the timeline! We began setup yesterday afternoon! Everything’s in motion! With your permission, we’ll continue our operation as planned, sir . . . unless you’d like to step in.

If the participants give the response that Perez is looking for they will receive a very positive response from Perez, but later in the simulation they will suffer the consequences.

FIELD COMMAND POST–PEREZ GETS CARTE BLANCHE

PEREZ

Smooth as glass, sir! That’s how your first full day here is gonna be!

If the participants give the correct response, then Perez will acknowledge the response and the reinforcement will come from the other person present in the scene (First Sergeant Jones). Of course, the most positive consequences of the correct decision will only be learned much later.

FIELD COMMAND POST–CAPTAIN WANTS CONTROL Perez looks down at the ground with some concern then looks up and smiles a trifle uneasily. He doesn’t see Jones coming up behind him, within earshot.

You’ll know about everything that’s happening, sir.

Jones gives a thumbs-up.

JONES

We’re all for a hands-on CO., sir! Oh, by the way. We’ll be getting a SITREP from our MP detail any minute! They should be fully deployed now!

First Sergeant Jones has much purer motives; he wants the Captain to succeed and wants to help anyway he can. But Jones, like everyone else in the world, has his own weaknesses. Jones is old school, and has lots of experience with and confidence in old school motivational techniques. He feels that he is a great motivator. Even though he can be, he is not always.

FOOD DISTRIBUTION AREA

In the background, we can see the wayward Afghan militiamen, the soldiers who found them, and Lieutenant Cho. We enter as Perez and Jones are already discussing the situation with the Captain.

PEREZ

(TO JONES)

I still don’t think we have a problem!

Jones, squared off with Perez in front of the Captain, looks angry.

JONES

Lieutenant, we’ve got Afghans wandering around inside our perimeter like they’re at a resort! You can’t call that managing security! The Civil Affairs guys can’t be doing much at their checkpoints! They gotta get with the program!

PEREZ

Let em be, Top! They understand the situation! They know their jobs!

Sir, just in case they don’t understand, I’d like to give them a little motivation talk, Bravo style!

PEREZ

(ANNOYED)

You’re just going to tick ‘em off! Give them time to fit in with Bravo Company! They’ll come around!

JONES

Sir! Requesting permission to give a pep talk to Civil Affairs! Make them see things the way the infantry does!

In this case Jones overestimates his own motivational powers and eventually it takes a combined effort of Jones and Perez to get things back on track. The ability to gain a quick understanding of the personal strengths and weaknesses of subordinates is a critical task that all leaders have to master to be effective. It is also a challenge to the creators of the scenario who need to understand their characters to their souls. Hollywood has developed a tool to aid in this effort and it was used in all the projects that Paramount Pictures did with the military.

CHARACTER BIBLES

The key to creating believable characters is to determine who they are and what they want. That is, to answer the actor’s inevitable question: “What’s my motivation?” In Hollywood, TV shows and movies require that the writer of a screenplay create character bibles in which the writer invents and documents each major character’s life experiences and goals. Once these things are known, the characters can be written in a believable, consistent, and useful manner. In the cases of Perez and Jones, the screenwriter detailed their childhoods, the lives of their parents, their educations, marriages, accomplishments, spoken goals, and secret desires. Some of this documentation was turned into dossiers: text files within the simulation that the Captain could access and read as he or she took command and began to deal with personnel. The following is a sample of the character bible created for Lt. Perez (developed by Paramount for the ICT):

First Lieutenant (and XO) Ricardo Perez

Ethnicity: Mexican American. Height: 6′2″. Age: 24. Hair color: black. Apparel: officer uniform.

Military Service

Commissioned as an officer in 2001, after four years of enlisted service. Went to Army Ranger School, Army Airborne School, and the Bradley Fighting Vehicle Leader Course. Platoon Leader for Rifle Company and HQ Company at Fort Carson. Very recently deployed overseas. Platoon leader for HQ Company in Qatar. Deployed in Afghanistan with new responsibility as Exec Officer (XO) in Bravo Company, 145th Infantry Battalion.

Backstory

Born just before American hostages were taken in Iran, Ricardo grew up with two brothers and two sisters in Norco, California–a dusty, hot, semi-rural stub of northeastern Orange County, where horses are common, a slaughterhouse lies not too far away, and lower middle-class Latinos and Anglos commute miles to work in order to pay the mortgage on inexpensive tract and pre-fab homes.

His father, Sergio, a first-generation Californian, runs a gardening service in Pomona, and served in the Army in the last days of the Vietnam War. Coming home, Sergio took a few classes at Mt. San Antonio College, met his future wife Lorena, but had to take care of a dying alcoholic father, who ran a desultory one-man gardening business. Beginning to raise a family, Sergio realized he could build up his father’s business, and now runs half a dozen crews. While Sergio may not be living in Beverly Hills, he and his wife have raised five kids and head to Las Vegas for weekends several times a year.

Ricardo was always glib, charming, a go-getter when he set his mind to it. He grew up a typical Southern California kid, but the there’s-nothing-to-do-out-here mentality of outlying Southern California communities lead to his ignoring classes, racing street cars, and getting high. Sergio dreamed of his oldest son getting into UCLA, but Ricardo’s lack of discipline meant he has a tough time passing community college classes, before a run-in with the law made him take stock in who he was and where he was going.

Not a fan of the Army himself, Sergio nevertheless encouraged Ricardo to enlist. The enlistment gave Ricardo a chance to break away from Norco and see the rest of the world.

In the Army, Ricardo excelled. The boredom factor disappeared. The military gave him just enough structure to fully realize who he is, and his innate charm came to the fore. Ricardo liked being a soldier enough to apply for officer training school. He advanced quickly, and soon returned to college to finish his A.A. and begin building credits toward a bachelor’s degree.

Figure 12.1 Dossier of First Sergeant Jones, part of participants’ briefing kit. Created from the Jones character bible.

The Perez character bible goes on to describe his education, marriage and divorce, hobbies, and opinions about Captain Moran and fellow officers. It also outlines his personal and professional goals, especially as they apply to the mission at hand. In this way the writer will have thought through the character’s motivation at every moment of the simulation experience.

CREATING CHARACTERS TO SERVE THE LEARNING OBJECTIVES

The challenge of creating complex and realistic characters for a simulation based on teaching points is finding opportunities to employ the character. A training simulation storyline may require one or two identified personalities and many nonspecific people. The key is to combine these nonspecific people into single personalities as often as you can. In this way you create a small set of consistent characters who will appear regularly throughout the simulation.

For example, in Chapter 2 of our simulation story, we introduced a very senior NCO named Command Sergeant Major Pullman who is present at the food distribution operation in order to make a documentary video about it. Pullman asks the Captain if he can make movie extras out of some of the men who are involved in a key part of the security preparation. This request will affect the manpower assigned to the mission and is an immediate challenge to the Captain’s command. We made this confrontation a key high stress decision point in our simulation.

Having created one dramatic moment with Sergeant Major Pullman, we could then have forgotten about him and used different characters to deal with other teaching points, but we did not. Instead, we chose to use Pullman again and again. As noted, Pullman questioned the overall location of the distribution site. He suggested that the entire operation should be moved to a better spot. Using Pullman to address this point allowed us to continue to build tension. Finally, we had Pullman criticize one of the junior officers in the unit and urge the Captain to remove him from the operation. Once again, we added another dimension to the decision because the recommending officer was Pullman, someone who brought a good deal of complexity to each of the decisions he was involved in. Introducing a self-involved character who comes in from outside the unit and begins to question decisions, challenge authority, and create conflict is a terrific ingredient in any story. If you can employ such a character in the service of the learning objectives, there is greater continuity to the story, greater complexity to the exercise, and a more compelling and interesting learning experience.

CHARACTERS REPRESENTING OPPOSITE POINTS OF VIEW

Because the Leaders project is about decision making, the principle nonplayer characters are able to play another valuable role: they can represent opposing decision options. On the issue of whether or not to seek the advice of experienced people before addressing a warlord who has arrived on the scene, First Sergeant Jones argues that it is critical to do so, but the more impetuous XO Perez provides arguments about why it is better not to waste time, but to respond immediately. The logic of these positions is well grounded in the background personalities and the goals of these characters as defined in their character bibles, so they provide a natural way of presenting both sides of the argument to the user before the decision is made. Here’s an example, from the moment when the warlord and his troops appear on the ridgetop overlooking the distribution site:

AT THE FIELD COMMAND POST

PEREZ

(TO THE CAPTAIN)

Sir, we need to send someone up there right away. Otherwise we’re just going to keep guessing about their next move. And I don’t have to remind you that the clock’s ticking on our operation.

JONES

But Lieutenant, I’ve gotta find out the protocol first. If we just go charging up there, no telling what we’ll unleash.

PEREZ

Sir, we don’t have time for conferences and meetings and running things up the chain of command. You have to show you’re in charge and the only way to do that is to get someone up there now, to find out what they want.

JONES

We don’t know the best procedures here, Lieutenant. I think we need to get the Command Sergeant Major and Civil Affairs to give us some input.

PEREZ

Sir, what’s your order? I can put together a team to head up there right now. Or we can go Top’s way on this and gather up some personnel for a consult.

SOLDIER

First Sergeant Jones, look!

UP ON THE RIDGE–WARLORD HAS A GUN

The warlord stands up.

He extends his hand and an AK-4 7 is handed to him by one of his men. He keeps the weapon pointed down but turns left, center, and right surveying the scene in front of him.

FIELD COMMAND POST

PEREZ

We don’t have any time, captain. What do you want to do?

In the Leaders simulation Perez and Jones represented opposite sides of most arguments and so could help the hero/participant explore their complexities. We had to take great care to make sure that their opinions were internally consistent and yet each character was correct an equal amount of the time. Otherwise, the Captain would begin to make decisions based solely on the track record of the person who made the recommendation.

Another dramatic use of an NPC occurred in the final simulation exercise that we created for the ALTSIM project. In that exercise we employed a character whose whole purpose was to lead the Captain in the wrong direction.

ARGUMENTATIVE CHARACTERS

In the second version of the ALTSIM simulation, the Battle Captain was in a tactical operations center (TOC) commanding troops in the field. The crew of the TOC was monitoring a cross-border incursion into a neutral country by troops lead by Colonel Kurgot, a hostile warlord in a neighboring country. Kurgot’s goal was to encourage the Captain to send forces to oppose him and then to lead those forces into a city that had already been infiltrated by his supporters. Once in the city, the Battle Captain’s own forces would be outnumbered and destroyed.

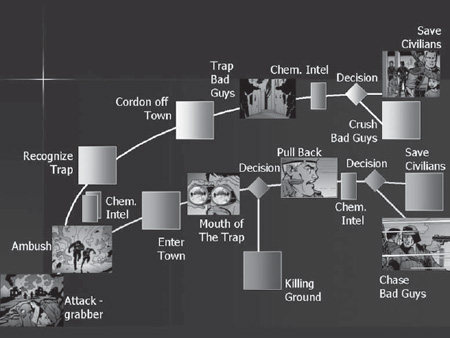

In this simulation there were parallel arcs to the story: the arc in which the Battle Captain allowed troops to pursue Kurgot into a trap, and the arc in which the Captain outwitted Kurgot and avoided the trap.

Remember that the Battle Captain is away from the action in a command center and has to communicate with soldiers in the field under the direction of a field commander. In this case, we named the field commander Red Hunter. The critical decision came when Red Hunter asked the Battle Captain in the command center for permission to pursue Kurgot. Red Hunter’s function in the exercise was to operate as an obstacle, encouraging the Battle Captain to take the bait and order his troops to follow Kurgot into the trap. The Battle Captain in the TOC had enough information to recognize the trap if he listened to his subordinates who were monitoring the incoming intel. But Red Hunter, fresh from what appeared to be a successful strike against Kurgot, was eager to pursue his enemy and did not want to be distracted. Being in the field, he was more than a little impatient with a person giving him orders from behind the lines.

In the critical exchange and throughout the remainder of the simulation, he continued to urge the Battle Captain to do the wrong thing. His hostile attitude created a whole new level of stress in the simulation and, at the same time, helped teach the Battle Captain (participants/heroes) how to deal with strong-willed field officers who do not always see the entire operational picture.

As in the Leaders simulation, the ALTSIM participant talked to Red Hunter by typing text into a computer, which then used natural language processing to select the appropriate prerecorded audio and video responses. Here is a sample response from Red Hunter that shows not only his desire to pursue his prey, but his hostile attitude toward a Battle Captain who is trying to give him a contrary order.

Figure 12.2 The two arcs of the ALTSIM RAIDERS scenario in which cross-border incursions draw American troops into a confrontation with Colonel Kurgot and his troops. The confrontation is an ambush, forcing the Battle Captain to choose between two paths:one leading to safety, the other leading to defeat.

Participant

I want you to pursue Kurgot at a distance. Monitor his progress and rely on air intel for added information. Let’s see what his objective is.

Red Hunter

In my book you break the bastard’s legs before he has a chance to get near his objective. Need you to rethink your position! Over!

CHARACTERS WHO PORTRAY CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

Story and character go hand in hand and this is never better understood than when trying to tell stories and employ characters to portray cultural differences. In a sense characters such as Lieutenant Perez and First Sergeant Jones can be thought of as illustrations of the cultural diversity of the US Army. Because they are well-rounded personalities and their backgrounds have been fully explored in the character bibles, they should help soldiers of other ethnic backgrounds understand something of the culture that they represent. But their individuality is also an important factor in their development, and so Perez, for example, is not present in the story to help people understand how to relate to soldiers of Hispanic origin. He has a dramatic role to play as an individual and that role is not essentially about his ethnicity.

But stories can turn on issues of cultural diversity and it is in these situations (when the culture itself becomes an issue) that specific lessons about cultural diversity can be learned. In the Leaders simulation, Omar, a local warlord, appears and is interested in participating in the mission. As seen in the discussion earlier in this chapter, there is some disagreement between the characters in Leaders on exactly how to deal with Omar. Eventually, Captain Young will meet with the warlord, and again, he will be getting advice from all sides on exactly what to do and say. We chose the meeting as the perfect place to introduce and deal with our teaching points that had to do with cultural diversity. We used the character of Omar to illustrate the kinds of reactions one might expect when facing a person of his station and heritage. And we added to the interest and engagement by making the meeting with Omar the pivotal moment when the warlord would either choose to support the mission or not. That choice, it turned out, would be the key to the mission’s success, because the Captain would need Omar’s support, not interference, to complete the mission successfully.

Figure 12.3 Warlord Omar who can play a major role in the success of the food distribution operation in the Leaders simulation.

The US Army in Afghanistan had military leaders who were involved in such meetings and this story-based rehearsal of such a meeting was clearly a way to drive their lessons home. But it was not the story situation alone that helped teach the lesson. It was the well-crafted, nonstereotypical characterization of Omar that made it so effective. The character was developed through a highly evolved character bible, interviews with soldiers who had met with such warlords, and experts in the native culture who understood the psychology and motivation of such men. Even the actors who played the roles were allowed to comment on the proper turn of phrase and expression, all of which made this element of Leaders a most effective use of character.

SUMMARY

We’ve talked about the creation and uses of NPCs and stressed the value of creating character bibles to ensure consistency in their actions and motivations. We’ve explored ways to build characters to serve learning objectives and the needs of the story. We’ve also shown how two or more characters can represent opposite sides of an argument so that the participants can make more informed decisions.

The complex tasks involved in character creation can seem daunting to any author, screenwriter, or game designer. A tremendous amount of detail must be worked out before one word of character dialog can be written. Nevertheless, no one will ever question the richness and realism that these characters bring to a story. It is also worth noting that the same care and dedication should go into the forming of the minor NPCs as goes into the development of the hero and the major supporting cast.

But as challenging as is the creation of those NPCs, imagine how much more care and dedication must go into the formation of the personality who will serve as that great looming obstacle for the hero. That task is vital because, let’s face it, there is nothing more valuable to a story—more compelling, engrossing, or juicier—than a really good villain.