23

Interactive Video and Interactive Television

INTERACTIVE VIDEO

Interactive video is a term that has been around a long time. Since the development of the laser disc in the early 1980s, corporate training centers have combined computer menuing systems with random access laser discs to provide video responses to data entered into computer systems either by individual participants or by representatives of those participants.

In the Final Flurry exercise, the instructors played the latter role. Their computer systems allowed them to send data and digitized video clips directly to participants’ laptop computers, but it also provided control of laser disc players that presented video segments on a large television screen at the front of the room.

Daily updates of the state of the world were stored on the laser discs and the instructors could present these updates through a simple menu selection. Because there were various paths through the media, the instructors were also prompted to select those updates that matched the probable outcomes of the decisions that the participants made.

Similarly, the instructors could select comments from the National Security Advisor that matched the participants’ decisions and recommendations and use them to give assignments that would shape the rest of the day’s work.

The instructor could also assemble the president’s daily state-of-the-union address from a set of video responses that would match the recommendations by the participants. In this application, the laser disc actually strung together the series of video clips of the president as though they were a single speech. Changes in camera angles during the production made the presentation of the event seem like a single seamless discourse.

Finally, a variety of outcome scenarios had been prepared to accommodate the range of recommendations that could be chosen by the participants. The instructors could select and present those outcomes that were most appropriate on the large screen at the front of the room. They did this by accessing the outcome sequences through the computer menuing and laser disc system.

The use of interactive video in Final Flurry was unique in that it depended so heavily on the instructor as “the man in the loop.” The instructor acted as the system AI and decided which prerecorded media elements were most effective.

To a large degree the Leaders project represents the ultimate updating of what was done in Final Flurry. Video content, which can easily be stored on a DVD these days, was instead part of the 3D simulation environment. But the animated responses to user actions were complete scenes that were stored in their totality and called up from the digital database. Participants did not present documents to instructors who then interpreted the documents and made the media selection based on human judgment (as they did in Final Flurry). Instead individual participants typed responses into their own computers, where a natural language processor decided what their words meant and accordingly allowed the media selection to be done by the computer system.

While this totally automated system seems to be a far cry from the Final Flurry laser disc-based interactive video system, in reality, the underlying instructional design, logic, and branching structure is exactly the same. So in fact, laser discs should be thought of as stepping stones to the more advanced technologies used in presenting interactive video today. In the same way, all these systems contain the same pitfalls relating to rigid content that made us seek the development of more flexible synthetic characters as described in Chapter Fourteen. While access to prerecorded or pre-rendered video content is powerful and of a very high quality, the trade off is lack of flexibility, which means that the video presentation may not respond perfectly to all the details of the input that the participants provide.

INTERACTIVE TELEVISION

In the commercial sphere, interactive television (now often called “enhanced television”), or iTV, has been ballyhooed since the 1980s. However, in anything other than tiny but controlled tests, commercial iTV only began real deployment with the emergence of digital interactive technologies in the late 1990s with both the maturation of the World Wide Web and the gradual deployment of modern set top boxes (STBs) and digital video recorders (DVRs). iTV use in the United States is only beginning to accelerate in growth; its penetration remains substantially less than the usage of iPods, DVDs, and broadband Internet. In England and other countries, iTV is far more prevalent.

Traditional television offers a broadcast (whether over-the-air, satellite, or cable) featuring one-way communication, the classic definition of “push” media. Loosely defined, iTV converts this broadcast to two-way communication: a viewer can interact with content. The broadcaster can then shape content based on that interaction, and the interactive dialogue between viewer and broadcaster commences.

iTV is being delivered via two methods: two-screen interactivity and one-screen interactivity.

iTV: Two-Screen Applications

To date, a majority of commercial iTV applications in the United States have been deployed using two-screen interactivity. Most typically, this has meant the simultaneous use of TV console and personal computer (desktop, laptop, handheld). More recently, these applications have also combined the use of TV console and cellphone.

Two-screen interactivity arose because the TV set has remained a “dumb” console for most users. The TV remains a one-way broadcaster of content, even though the broadcast is now delivered by cable or satellite system. Thus, all two-way interactivity occurs on the second screen. While this is undoubtedly (to use a time-honored engineering term) kludgy, it also reflects usage patterns of a substantial portion of the population: people are already accustomed to using their computer or cellphone simultaneously with a TV. Why not harness this usage pattern and lash both screens together?

The two-way content may be either synchronous or asynchronous to the broadcast, delivered via the Internet (see Chapter Twenty-Two for further notes on delivery of Internet content). Content synchronous to broadcast is likely to be more dynamic for the user/viewer. For example, a development in the TV broadcast will trigger content on the second screen, perhaps a poll, a quiz question, a factoid, an image, or streaming media. Synchronous content will require that the user continually focus on the broadcast screen, effectively merging the two screens into one feedback loop.

While the cellphone may seem like a less effective second screen (due to screen size, communication bandwidth, etc.), its diminutive size may be countered by the relative intimacy of the device, which means many users are actually more comfortable and likely to use it. With screen resolutions, bandwidth, and capabilities continually improving, the cellphone becomes an ever-more viable platform for shared or total content delivery. (See Chapter Twenty for detailed discussion on bandwidth and how cellphones stack up.)

iTV: One-Screen Applications

Set-top boxes, in real-world settings, have finally become robust enough to enable true two-way interactivity on the single screen of the TV console. Applications vary, everything from user control of camera shots (Wimbledon viewers in the UK, for example, can choose which game to watch and which angles they like) to user input selecting content (additional graphics, charts, text); voting in polls; taking quizzes; determining branching story direction; and much more.

Interactive content may appear as a separate window on the screen or as a transparent overlay on the main screen. The bandwidth available for upstream (i.e., user transmission) use remains miniscule compared to the bandwidth on the downstream (the TV broadcast), but will continue to improve in the years ahead.

TiVo, and similar DVR devices, offer another methodology toward one-screen applications, as content can be downloaded in the background prior to the actual simulation experience, and can then be triggered throughout a broadcast, creating the illusion of two-way interactivity (user interactivity is likely to be with the DVR-device only, selecting to view video stream one vs. video stream two, for example).

In the long run, it seems likely that one-screen applications will overtake two-screen applications. For now, however, second-screen devices generally offer more archival storage (good for tracking user history and performance), output options (printer, scanner, email, Internet, etc.), and portability (a user can bring his laptop to another location and display or output data collected during an iTV experience). In addition, usability and psychological issues could argue for the continued use of second screens (perhaps particularly cellphones) in some simulations. The two-screen experience may also better simulate certain actual environments.

iTV vs. Internet Delivery

Why choose iTV as a simulation delivery platform? To begin with, the TV console is still the best delivery system for full-motion, live action video. If video clips comprise a substantial portion of your simulation’s media assets, then this platform might be worth a look. However, iTV is a broadcast medium intended for wide delivery and numerous users. Building a one-screen iTV system is expensive and demanding, and probably only makes sense when plans exist for a number of simulations to be delivered to numerous, dispersed users over a period of months or years. Creating a two-screen iTV system is more feasible, but still requires considerable skills should synchronicity with broadcast events be desirable.

As one-screen iTV becomes more pervasive (via STBs, DVRs, and newly developed Internet Protocol Television [IPTV]), it will become increasingly possible for government or private sector entities to lease a “virtual channel,” which will essentially use the Video On Demand (VOD) features that TV distribution companies (phone, cable, satellite) will have in place.

IPTV, in particular, offers the potential for anyone to become a broadcaster, as the TV becomes just another Web-enabled node. This technology makes “narrowcasting” (highly targeted broadcasting) to intracompany sites more practical. (See http://www.iptvnews.net for more information on IPTV.) In addition, new middleware services like Brightcove (http://www.brightcove.com) will more easily enable the production and delivery of iTV narrowcasting.

These developments should make iTV delivery no more complicated than Internet delivery for training simulations. But this area remains the “bleeding edge” of technology, and probably argues for a longer development timeline on any simulation project.

Story-Driven iTV

Given the emerging commercial uses of iTV in the United States, it may appear that the platform will carry little story content and is only meant for user transactions and game show applications. In fact, the opposite is true. Even if the interactivity only involves quizzes, polls, factoids, and other primarily textual material, this content can be used to deepen and enhance the video content, often providing a hook or arc that will pull together disparate videos into a truly involving narrative.

If users have the capability to begin to select and direct camera action, they will begin building their own story narrative, and this ad-hoc narrative can then help to carry pedagogical and training content. Further video content can be “awarded” to users who answer questions, make selections, or fill out profiles. Showtime’s episodic drama The L Word has experimented with this approach under the umbrella of the American Film Institute’s Digital Content Lab. We are truly at the dawn of learning how to tell interactive stories, but the use of full motion video content offers rich possibilities for immersive and engaging narratives.

VIDEO PRODUCTION

Video is generally regarded as the most expensive of all media to produce. And though the creation of 3D virtual worlds with the accompanying need for quality assurance and difficult revisions may be giving it a run for its money, video is still something that needs to be approached with a healthy budget and a healthy respect for its complexity.

That being said, there are many things that can be done to exercise cost control and to get the most out of your video production investment. Let’s take a look at the various styles of media used in simulations and discuss the pros and cons of each.

Full-scale production is surely the most expensive and most difficult to pull off. Creating a complete new mini-movie on any topic is generally very difficult. We noted in earlier chapters that Leaders was based on a very successful film that ICT produced called Power Hungry. The film had a sophisticated script, well-trained actors, many extra players, music, sound effects, an expansive location, authentic sets, props, and a good deal of high-priced editing. The key characters are complex and require good performances from the actors. Certainly the film was extremely well received by the Army participants who viewed it. But the key to its success was its believability that was far easier to achieve in Hollywood, with experienced writers, directors, and experienced actors all around.

Today’s sophisticated audiences are accustomed to prime time television commercials and $200 million action movies. They are immediately turned off by amateurish productions. If you’ve set your heart on a Classic Hollywood-style production, beware. It will be very hard to achieve. If you must go this way make sure you have a good script with believable dialogue. Hire someone who knows the demands of directing. Get someone who knows about lighting and won’t allow ugly shadows to distract from your production. Get the best actors you can find, make sure they know their lines, and rehearse them over and over again. Choose inexpensive “real” locations over limbo sets with limited props and borrowed furniture. Shoot outside whenever you can to simplify the lighting requirements. Use tight close-ups of characters to eliminate the need for detailed backgrounds. Hire an experienced editor or learn a good, well-rounded editing program like Final Cut Pro yourself. And good luck.

If you can’t afford the classic Hollywood style or don’t have enough experienced colleagues, go to a production format that is still acceptable but doesn’t require the polish of Hollywood. Try the hand-held style of many of today’s independent films, or go for the gritty news format kind of show, which because of its immediacy is allowed to be far less polished.

In the Final Flurry and ALTSIM projects, the Paramount Pictures team produced video content modeled after news broadcasts. This lent itself to the military situations that made up the main content of the simulations and allowed us to hire people with news experience. Newscasting, while still requiring a certain polish, uses a simpler kind of presentation. Newscasters are trained to be unemotional and as such are not required to exhibit the intonations of character that would make their performance less believable.

Also, news sets are fairly simple and as such are easier to replicate. Sometimes internal, corporate TV production groups have news sets of their own. Sometimes the local TV station will make their news sets available for local production.

Stock footage is always more believable than any attempt to restage an important event. Local and national news companies often sell their stock footage on a limited use basis and they give discounts for training or educational uses of the material.

It is sometimes difficult to achieve a real, believable green-screen effect, in which the actor/narrator is keyed (superimposed) over the stock footage background, but if you have an editor who is skilled at rendering such effects, and you have the time, it is definitely worth a try. You can have your newscaster standing in front of the White House, just key him or her over some footage of the White House. And make sure there is a little movement in the scene (a fluttering flag, an occasional car driving by). Today’s sophisticated audiences know to look for that.

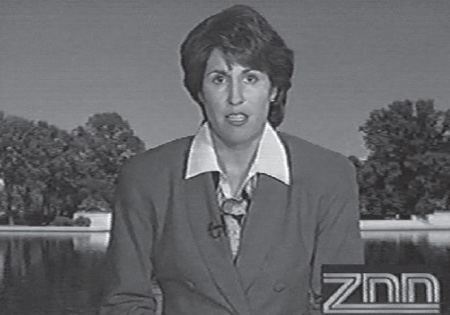

Figure 23.1 Jackie Bambery, a professional newscaster keyed in front of a Washington DC location for the Final Flurry Exercise.

Producing video segments featuring actors portraying characters in an interview, public announcement, or press conference brings up some of the issues presented when discussing classic Hollywood-style productions. But then these are usually easier to achieve than dramatic scenes involving dialogue. Get the best actor you can. If you can afford an over-the-lens teleprompter, use it. It will make the actors delivery much more believable because the actor will be looking directly into the camera. Sit the actor in a comfortable position. Go for the finest lighting possible.

Because press conferences and interviews are often staged in impromptu settings, the backgrounds do not have to be as realistic as in a classic Hollywood set. Use a state or national logo, a map, the flag of the relevant country, or a classic painting that fits with the character being portrayed.

Again, keep the shots tight. In ALTSIM we rented a military Humvee so that we could show our Lieutenant in the field. But in the end, all the shots were so tight that we never saw the Humvee, and the rental money was wasted. Generally speaking tight shots of a good actor are always more believable than elaborate long shots that attempt to portray more of the scene.

Keep the actor’s lines as concise as possible so the speech or announcement does not drone on and lose the audience. Make sure that you think of and shoot every single possible statement and remark you could ever need. If you later think of one interactive response or one conditional statement that needs to be added you will probably never match the lighting and the sound quality of the statement again, and you will probably have to rerecord the entire set of statements all over.

Use voice over narration whenever possible. Well-directed actors reading lines off-camera are easier to control and more accurate. But if there is any chance at all that dialogue might be delivered on-camera, shoot all of it on-camera, then all the audio will match. If you can’t find that elusive stock footage shot, you may be able to cut to the newscaster.

Use diagrams, titles, and maps as full screen graphics. It is easier to create a good-looking graphic than it is to light an actor and get the lines perfect. The presence of the graphic will upgrade the entire video presentation. And, since graphics are basic elements of many newscasts and press conferences, they will add an element of authenticity to the proceedings. If graphics are good, animation is better if it looks like those in newscasts and announcements.

Finally, video clips that are examples of a specific situation are especially effective if used on their own. In Leaders we needed to show video captured by a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle); we were able to acquire that kind of footage from the military and deliver it as a desktop video clip. We needed a shot of a hard rain. One of the authors walked out his front door one March afternoon, pointed his camera over the tops of the trees, and took the shot. Shots of fires, riots, weather conditions, auto accidents, etc. can be purchased from your local news station, or even captured with your own camera. Turn these shots into desktop video clips where the quality is supposed to be low anyway or attach them to e-mails and you’ve added another media element to your presentation.

SUMMARY

Interactive Video began as the control of random access laser disc video by computer multimedia systems. In Final Flurry, it was the instructor who interpreted the decisions of the participants in the classroom and chose the appropriate video clips to play on the large TV system in the front of the room.

Current forms of interactive video include clip selection by AI systems built into the individual computers of simulation participants, as in the Leaders project. These days, video elements can be stored on DVDs or in libraries of digital video files resident on the computer itself.

iTV is beginning to emerge as a rich and exciting platform for the building and delivery of a simulation that relies primarily on video content. iTV is truly a broadcast medium, and at this time, is probably out of the reach of most government and private sector entities. However, as Video on Demand, virtual channels. and Internet Protocol Television are made readily available by TV delivery systems (cable, phone, satellite), iTV will become a logical platform for delivery of certain simulations.

Video production for any of these approaches should be governed by a healthy respect for the cost and complexity of the production. Classic Hollywood styles are extremely difficult to imitate and will often be judged amateurish. Independent film styles or news formats are much easier to achieve, especially since many news sources will sell their footage and professional newscasters are everywhere.