3

Collaborative Distance Learning

In 1999, the University of Southern California hired Richard Lindheim away from Paramount Pictures. Lindheim was an Executive Vice President in the Television Group at the time and was the leading force behind the Paramount/DoD collaboration. USC had received a large research grant from the United States Army to set up a university-affiliated research center, and critical to the affiliation was the bringing together of military training researchers, university scientists, and the Hollywood creative community. Lindheim was the perfect man for the job in many ways. His relationship with the DoD had already given him experience with the world of military simulation training. More importantly, he knew many of the most important people in Hollywood, he had access to the inner circles of the creative community, and he was an impresario. He knew how to stage events that could dramatize the power of creative stories in military training. And he could explain things very clearly, clearly enough for the generals who became frequent visitors to USC to understand the concepts and the technology behind the endeavors of his research center, which was officially titled the Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT).

One project on the ICT agenda involved ongoing collaboration with Paramount and its creative group. The project’s goal was, in some ways, to continue the StoryDrive effort initiated by the Department of Defense. That is, it sought to create military simulations that used Hollywood storytelling techniques to heighten tension and make them more memorable and effective. Unlike the StoryDrive effort conducted for the DoD, however, the first order of business at the ICT was to construct the technology that would make StoryDrive possible.

The new project was launched in 2001. After considerable analysis and consultation with the Army, Paramount and the ICT proposed that the project focus on leadership skills involved in the running of a tactical operations center in Bosnia. At the time the Bosnian conflict was at its height and tactical operations centers (TOCs) were a key force in the growing success of the operation.

The ICT project was named the Advanced Leadership Training Simulation, or simply ALTSIM. Nick Iuppa again headed the Paramount effort, this time under the guidance of Paramount television executives Steve Goldman and Bob Sheehan. Larry Tuch continued as head writer and Dr. Gershon Weltman came on as creative and military consultant. Dr. Weltman was the former president of Perceptronics, the company that had built SimNet, the first major military simulation. Nat Fast of Empire Visualization provided simulation architecture and development, and Janet Herrington served as executive producer of the entire effort. ICT’s Dr. Andrew Gordon became the lead researcher on the project under the direction of Dr. Bill Swartout, ICT’s Director of Technology.

General Pat O’Neil, having recently returned from Bosnia himself, became the content expert for the project and worked with writer Tuch to design a story that would challenge the members of a simulated TOC. The scenario that O’Neil and Tuch developed was based on a real incident that had happened in Bosnia involving members of a weapons inspection team visiting a small village. The team discovered that all the weapons in the local weapons storage site were missing. Moreover, when they attempted to leave the area they found that angry villagers had surrounded the site and would not let them go. The lieutenant in charge of the team radioed the TOC asking for assistance, and the members of the TOC, each a specialist in a different area, had to pool their knowledge to determine the best course of action to save the endangered inspection team.

O’Neil and Tuch’s design provided a backstory that added true urgency and danger to the event. Tensions were already high in Bosnia as local residents who had fled their homes under pressure from the previous government were now being allowed to return once again. But buried deep in the intelligence that Tuch wrote for the simulation was information about a local dissident leader and exponent of “ethnic cleansing” who had much to gain by seeing the Americans embarrassed by a violent incident in a local village. The revelation of this character and his intentions was to play an important role in the rescue strategy selected by the members of the TOC.

TOCs can be created in different configurations. They are often set up in a several trucks backed together so that officers can work inside and set up communication systems from which they direct operations. The staff consists, in part, of a leader (Battle Captain), an operations noncommissioned officer (Ops NCO), an intelligence officer, and liaison officers for other units in the area. For the sake of simplicity the designers of the ALTSIM exercise limited the number of soldiers in the TOC to three: Battle Captain, Ops NCO, and Intel Officer. To train collaborative skills, information was usually sent to one of these three officers and not to the others. As a result the team had to exchange information to gain “situational awareness.”

In military terms one major component of situational awareness is “ground truth”—the knowledge of what is really happening on the ground during a battle or some other event. In the case of the ALTSIM story, the situation was not yet a battle and the members of the TOC did not want it to turn into one.

As in the StoryDrive design, the decision makers in the TOC received information from various sources. As often happens in current military situations the US news media is on the scene very early and that fact was taken advantage of in the story. One of the first bursts of information received in the TOC is a news story describing the plight of the returning refugees. The dissident leader mentioned earlier is interviewed as well, giving his opinions on the dangers that can result from allowing the refugees to return.

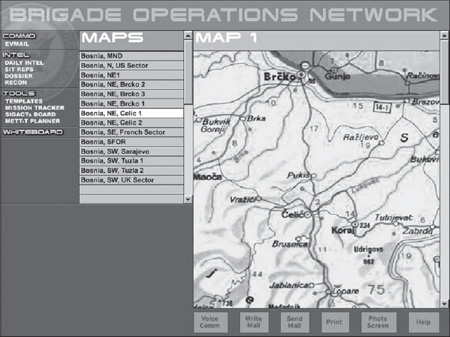

As pieces of information come into the TOC the Battle Captain must choose a course of action. Radio chatter is everywhere, members of the team are shouting out observations based on new pieces of intel that they have found or incoming e-mail messages. The Ops NCO can monitor images coming in from air reconnaissance, suggesting the availability of various rescue routes if the Battle Captain wants to consider them. Maps of the area, which would normally hang on the walls of the TOC, are made part of the computer interface and are consulted as options are weighed.

The ALTSIM simulation as conceived fed information to the participants in the simulated TOC but it did not force any actions. Instead, it waited for text input from the members of the team, which it read and interpreted and used to choose the next media elements to send, much as had been done in the StoryDrive scenario. As created, the ALTSIM story had a specific path (story arc) that it sought to follow. What happened if the members of the TOC made decisions or initiated orders that did not follow this arc? This issue is at the heart of realistic story-based simulations and became one of the core problems that the ALTSIM team attempted to solve.

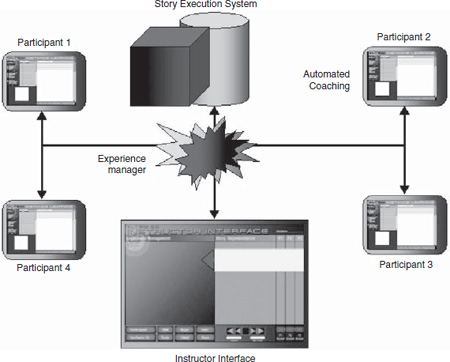

Dr. Andrew Gordon (the PhD researcher assigned to the project) came up with an interesting solution, which was employed in the ALTSIM project and later published in the Proceedings of the 2003 TIDES conference held in Darmstadt, Germany, and subsequent research conferences. It will be described in detail later in this book. Simply put, Dr. Gordon proposed that the simulation story be described as a series of expectations in the mind of the story’s “hero,” the Battle Captain. In each case when the hero took an action it should match that list of expectations. When, however, the hero took an action that moved away from the list, its effect would be to move the story off track. To keep the story moving toward its intended outcome then, something would have to happen to put the story back on track. In ALTSIM the mechanism that selected media elements and presented the story to the participants through their computers was called the Story Execution System; the system that tracked the students’ progress through the story and kept the story on track was called the Experience Manager.

In the ALTSIM story the TOC was equipped with the latest advanced computer information systems that presented all e-mail, gave access to intel and deep background, presented video from surveillance aircraft, displayed broadcast news, presented maps and allowed for their updating, and contained all military forms and allowed for forms completion online. The ALTSIM computer system was a mockup of future technology that could bring together every relevant piece of military information and make it all accessible and usable on the computer desktop. The system also featured Webcams and audio headsets so that every member of the TOC could see and hear the other on his or her own computer screen. This last feature meant that members of the TOC did not have to be in the same location to participate in the collaborative exercise. They could in fact be members of a virtual TOC where each member was at a different military base elsewhere in the country and the world, and yet, felt as though they were in the same room together.

The Story Execution System controlled the flow of media elements to the participants’ computers. The Experience Manager likewise selected and presented media elements on the participants’ computers. But the purpose of these media elements was often to push the story back on track.

Figure 3.1 A sample screen from the ALTSIM participant interface employing the mapping tool that was built into the system.

The media elements that would intervene in the story and block an entirely new story direction were called adaptation strategies. Dr. Gordon’s conception was that the simulation would have hundreds of these interventions at its disposal and would block actions that would take the story off track by applying the intervention according to a very strict set of rules—the first of which was: if possible, don’t block it. The intention was to make the employment of the adaptation strategies as seamless and realistic as possible, and if there was any way that the action could be taken and not blocked and the story continue on track, that was the preferred method.

These kinds of interventions were helped by the very structure of the military itself, where strict organization and procedures require formal actions be taken in order to make things happen. To initiate troop movement, for example, the Battle Captain has to issue an order and that order had to be formalized though some kind of documentation. So the system always knows when the Battle Captain has issued an order and what it is. The system also knew which documents had been opened, how long they were opened, and if they were forwarded to any other member of the team.

The military hierarchy also provided a mechanism for intervention. For example, the Battle Captain has a commanding officer (CO) who reviews his or her most important decisions. The CO can simply say, “Don’t do that,” and an action that might take the story off track would be nullified.

Among the information that the TOC was getting was a message that reported that there were movements of paramilitary troops toward the town of Celic. This was shown by cars observed crossing checkpoints and other clues. The Intel Officer was expected to start monitoring this kind of information.

Of course, the Intel Officer’s computer was loaded with all kinds of intelligence information about a great variety of events—very few of which related to the immediate problem at the weapons storage site in Celic. So, in a sense, the mission of the officer was to sift through the mountain of intel and piece together those few messages that had a real bearing on the actions that the Battle Captain had to take.

Since it was critical to the story that the Battle Captain be made aware of the movement of paramilitary troops toward Celic, the Experience Manager could send more obvious information to the Intel Officer until it recognized that the Battle Captain had become aware of the danger and had acted—sending a rescue mission to save the weapons inspection team before the paramilitary forces could reach the area and cause some real trouble.

As a check on the actions of the Experience Manager, ALTSIM once again employed the “man in the loop” strategy. It had an instructor workstation as a means of allowing an instructor to monitor the progress of the story. When the Experience Manager noted that the participants were doing things that would take the story in a direction that would not work, it first alerted the instructor and suggested that an intervention should be sent. It was up to the instructor to approve the intervention, or even to create an original message of intervention that might fit precisely with the conversations that the members of the TOC were having about what should be done. The instructor could, after all, hear the conversations—something that the computer system could not do.

In the course of the original story, the Battle Captain should instruct the Ops NCO to assemble a task force to proceed to Celic and rescue the inspection team. At the same time, he should send air support to intercept the paramilitary troops before they reach the town.

At this point another function of the Experience Manager came into play. Its purpose was not only to monitor the progress of the story and keep it on track, but also to assure the quality of the educational experience. If the participants seemed to be breezing through the simulation, the Experience Manager could add events to make things more difficult. For example, it could introduce fog into an area where the helicopters were supposed to land. That would complicate the air mission. It then would become necessary for the Battle Captain to determine an alternate use of air support, if any.

Figure 3.2 A breakdown of the systems that combined to create ALTSIM as it was demonstrated at the Institute for Creative Technologies.

While ALTSIM did follow one simple arc to the conclusion of its story, it did allow for multiple outcomes. The Experience Manager could calculate which decisions the Battle Captain made, and it could choose an ending that was appropriate to the quality of skill that was shown by the Battle Captain and the members of the team. In the ideal story, the Battle Captain made all the correct decisions and the rescue column reached Celic and saved the inspection team without firing a shot.

During the first year, ALTSIM was demonstrated to visiting military by using National Guard troops who acted out the simulation. Later, professional actors were used. By the end of 2002, a whole new scenario had been developed and members of the team could execute a true working simulation from start to finish.

At that time, a committee from the US Army reviewed the project and its research direction and recommended a significant change. What resulted was really a whole new simulation system focusing on commanders in the field instead of those in a tactical operations center. To accomplish this, the ALTSIM team had to move away from the development of training systems that focused on simulations of computer networks inside of command centers. Instead, they began to apply the concept of story-driven simulations to 3D worlds and virtual characters. In March 2003, the third and final collaborative effort between Paramount Pictures and the military was launched. It was called Leaders.

SUMMARY

The efforts of Paramount, USC, and the Department of Defense to initiate a system for creating story-based simulations extended into another project that was carried out for the United States Army at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies. The Advanced Leadership Training Simulation, ALTSIM, began with a focus on the technology needed to create a working story-based simulation. The system’s Story Execution System brought together various media elements to tell the story of an inspection team trapped at a weapons storage site in the Bosnian village of Celic. The story was told through the computers of members of a tactical operations center. The TOC officers had to share their information in order to arrive at a plan that would save the inspection team. The steps in the plan were implemented by sending orders through the computers in the TOC and, by monitoring these orders, the system could employ an AI engine called the Experience Manager to keep the story on track and propel it toward its required climax.