13

A Really Good Villain

I asked a gamer friend of mine to answer a pretty simple question. “Tell me something about one of the characters in a video game you’ve played recently.” He looked up from darning his socks (or whatever he was doing), and told me to clarify. “Not anything external, like appearance or the way they talk. I mean that character as a person. The kind of thing you know about someone after reading a good book.” He seemed a little surprised by the question, so I told him it was for an article I was writing.

This guy isn’t stupid, and knew what I was getting at. He thought for a little while, and eventually told me, “You know, games don’t usually do that.”

(From “The Importance of Story” by John Campbell)

In a sense, you could think of the supporting players in Leaders as adversaries. They have their own goals. These goals sometimes don’t match those of the hero, Captain Young. Executive Officer (XO) Perez wants to run the operation and is hesitant to give the Captain input. He represents one of the first obstacles that the Captain has to overcome. Yet, in the story structure described by Robert McKee and others, he is just the first level of conflict that our hero has to deal with. And the goal of overcoming that first obstacle and establishing control and authority in the operation will enable the Captain to serve the larger goals of the project: conduct a successful food distribution operation.

Command Sergeant Major Pullman has more subtle goals that are even harder to figure out. Like XO Perez he wants a piece of authority as well. The Captain must once again assert authority, this time in the face of someone from higher command, who could disrupt the operation and video tape the whole disaster as it unravels.

In the previous chapter, we mentioned that a warlord shows up and wants to participate in the food distribution operation that the Captain has to oversee. The warlord has his own goals, which seem dubious from the first and do not necessarily mesh with those of the Captain. Also, cultural differences made it more difficult for the Captain to understand the warlord and trust his motives.

Interestingly enough, the Leaders scenario, as we explained in Chapter Four, is based on a training film created for the Army by the Institute for Creative Technologies. In that film, the role of Omar the warlord was not fully explained, and it did not need to be because the film was a quick trip to disaster in which everything went wrong. But in trying to find a path to a successful outcome, our Army advisors agreed with us that Omar might just be the key to a positive outcome. If the Captain can see through the cultural differences, understand Omar, and assign an appropriate role to him and his men, the film’s negative consequences could be avoided. So the critical meeting with Omar in act 3 of the Leaders scenario, which we described in the previous chapter, gives the Captain and all the other players in the simulation a chance to get Omar on their side, so that he can help move the story to a final positive outcome. In any event, though Omar provides a challenge to the Captain’s leadership and decision-making skills, even if the Captain does not make proper use of him, he is certainly not the villain in the piece.

In fact, Leaders presents the most complex and difficult authoring scenario of all, because it is the Captain’s own weaknesses that led to the eventual disaster in the story. Like Hamlet, the Captain himself has the potential to be the villain. To make it a little clearer, we could use Bill Idelson’s terminology. The Captain’s own weaknesses become the obstacle. It was Captain Young and his inexperience that created the disaster at the end of the Power Hungry film, in which shots are fired and the crowd overruns the relief trucks. In the Leaders simulation, the participant/hero/captain takes the same path to the disaster, one decision at a time. It could be argued that any inexperienced officer given this situation would make the same mistakes that Captain Young did and would end up with an equally disastrous outcome. One way to build a gripping simulation story is to determine the weaknesses that the hero has to have to bring about his or her own downfall, and then construct the story as though it were a series of tests of increasing difficulty. Participants without experience in a given task bring that inexperience to the simulation. Bringing those participants face to face with those deficiencies over and over again in increasing degrees of difficulty until the obstacles combine into one massive, all-consuming obstacle is a perfect example of what McKee calls the “Education Scenario,” and as he says it is the ultimate scenario.

BUILDING FLAWS INTO THE HERO

Is it possible or valuable to have participants play characters with deficiencies other than their own? Not entirely. After all, the purpose of serious games is education and the objective is to overcome real deficiencies. However, in the process of overcoming their own deficiencies, participants can also build on some of their strengths. Can I become a battle captain who has, for example, a difficult time handling subordinates, though that may not be a glaring deficiency of mine? Can I play a captain who is easily distracted and has difficulty focusing on the most important issue, when I myself may be pretty good at handling distractions? Is it possible for the simulation to let me play a character whose deficiencies are different from mine and is there any value in that?

The answer is: of course. There is value because forcing participants to deal with the flaws in the characters they play only strengthens their performance. It is like asking a man to perform a task with one hand tied behind his back, knowing that if he can do it he will be able to perform the task much better when he has the use of both hands.

How do you build added flaws into your heroes? You, as the game designer, have control of the environment. You are the author, and we have all experienced the narrative tricks that great authors like Edgar Allan Poe can play when they want their heroes to possess great flaws. Poe and the poet Robert Browning, for example, had their characters approaching madness, and allowed us to see the world through their insane eyes. As the game designer, you can crank up the distractions, you can manage the flow of information, and you can distort the hero’s picture of the world until the participants are seeing through the eyes of people who have flaws in their vision. In turn, these flaws give them performance difficulties beyond those that they possess.

In ALTSIM, the Battle Captain in the tactical operations center had to rely on messages from his subordinates. We controlled the frequency and content of those messages; we could make them more or less confusing. We could build up the distraction in the cross-talk in the radio signals until that too began to simulate the noise in the head of a participant that had less ability to sort things out. We could speed up the flow of information, until the participants felt that it was more difficult to make decisions quickly. There were many tricks that we used to make participants feel that the faults they were experiencing were their characters’ and then their own, and not simply those created by the environment.

Of course, one of the easiest ways to build flaws into hero/participants is to use nonplayer characters to reveal those flaws. In ALTSIM, we designed a scenario in which there was an especially difficult officer representing a foreign power that controlled another sector of the country. The participants had to deal with that officer in order to achieve their goal. In one proposed scenario, the officer was not only a difficult person to deal with, but had a personal history with the participants and had a definite attitude about them. The participants could be briefed on the history of the relationship or could figure it out as the simulation progressed. But the participants had to account for personal weaknesses of characters even though they themselves may not really have possessed those weaknesses. If the foreign officer was difficult to deal with, the participants had to figure out how to overcome that difficulty. If they were successful, the participants would master some pretty important interpersonal skills, but they could just as easily fall prey to the contrary attitude of the foreign officer, respond in kind, engage in escalating negative interpersonal strategies, and in the end become the kind of difficult person that the simulation is trying to teach them not to be. In that situation, the simulation has bated them into becoming the villain in that part of the simulation story.

One way to achieve a similar effect is to have participants play characters who are brought in to replace people with a very established way of doing things. The behavior of deciding whether or not to maintain practices that have already been instituted is not the same as finding and correcting your own faults, but there can be similar judgments involved. In Leaders, the participant played the role of a captain who was brought in to replace Captain Moran, a commander who had held a very tight reign on his troops. The participant was constantly reminded of Captain Moran’s practices. If the participant wanted more information we had prepared detailed responses for subordinate officers who would go on and on about how Captain Moran would handle each and every detail of the mission. In truth, Captain Moran was not a perfect CO and some of his practices were not the best. In the Leaders scenario, part of the new participants’ job was to determine the weaknesses of the leadership position, which they now held, as instituted by the precedents set by Captain Moran. In a sense, their troops had expectations about the way the leader would behave. If Captain Moran had weaknesses as a leader, the new captain would have to figure out what they were and somehow deal with the expectation of those weaknesses. In many cases the new captain would have to change policies and reverse procedures and practices as set by Captain Moran. Of course, if the entire problem with the operation were the fault of the shortcomings of Captain Moran, then he would be the villain of the piece—and the task for the new captain would be to deal with the ghost of Captain Moran.

BUILDING THE ULTIMATE VILLAIN

Philosophically, the ultimate villain may be the hero, but dramatically it may be far easier to create an external villain who represents the forces that the hero must oppose. In ALTSIM we talked about putting a face on those forces. In other words, it is not enough to say that you are being opposed by a foreign power. It is better to identify the person who represents and exercises that power and develop an understanding of him or her. The job for the developer of simulation stories is to create those personalities, make them interesting and complex, and give them the traits needed to challenge the skills of the simulation participants.

In our first ALTSIM scenario, set in Bosnia, it was our job to represent the forces that made US involvement necessary. We needed to put a face on a minority who were in favor of ethnic cleansing and displacement of people whose ancestors had lived in the region for centuries. These people did exist and there were leaders of such movements. What would such a personality be like? In our media savvy world, they would understand the power of news sources. They would be able to articulate their positions logically. They would be able to make a case for their goals. They would be able to talk to the press. They could be charming and charismatic, so much so that it might be the job of the participants to see through their charm and recognize the reality behind it.

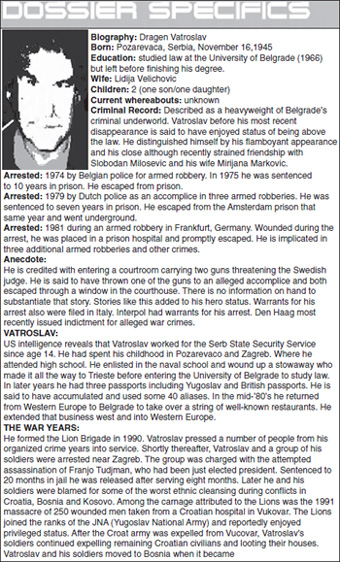

In Idelson’s words, the writer, on spotting this person coming toward them, could not run away but would have to dare to walk right up, look them in the eyes, and say, “Now what?” In fact, it is not enough to look into their eyes, it is necessary to look into their souls. The writer has to understand them and what motivates them, even learning to see things through their eyes and sympathize with them. This is where the character bible becomes so important. It is through the character bible that writers force themselves to explore the factors that motivate and drive the characters. Our villain in the ALTSIM Bosnia scenario was named Dragon Vatroslav. He was a well-educated, colorful man, but also an outlaw. He had been involved in international robbery and had served prison time. Yet at the time of our story, he had become a successful businessman and established a relationship with Slobodan Milosevic. Still not giving up on underworld activities, he organized his own army to take advantage of the ethnic unrest in his native state, the former Yugoslavia. He expressed himself very well. When a national news organization went into Bosnia to cover the incident at the weapon storage site, which was the basis of our simulation training, Vatroslav was the first person they talked to on camera. If the Battle Captain had the TV on during the simulation, he would have seen and heard his adversary.

Vatroslav was eloquent in describing the political consequences of forcing the repatriation of the minority into Bosnia. He cautioned against the participation of the United States in the relief effort and urged them to get out. He defended the crowd who had trapped the inspection team in the weapons storage site. But, in truth, what lay beneath that eloquence was a deep hatred for the ethnic minority. Generations of distrust and violence on both sides had turned him into a predator who was good at hiding his intentions, yet was constantly on the offensive. It became the job of the participants in the ALTSIM simulation to recognize that Vatroslav himself had orchestrated the attack on the weapons inspection team, and at that very moment was summoning paramilitary forces from the surrounding countryside to create an international incident. If the Battle Captain could piece together the true picture of Vatroslav’s plan, it would be clear that the required response would have to be much more complex than a simple rescue. Time was of the essence. The action itself might not be able to be contained to the town itself but might include much of the outlying area. Movement of troops and ammunition was as much a factor as the action surrounding the storage site. The challenge for the Battle Captain was not to engage Vatroslav in any kind of hand-to-hand combat, but to recognize his ruthless nature and the scope of his plan. Only when thinking strategically with a true awareness of the entire picture could the Battle Captain mount a successful operation. All this information was being fed to him through the simulated systems of ALTSIM’s communication interface, often buried amid reports on much more mundane military operations. Also, to pull off the resolution of the exercise would require gaining the cooperation of that antagonistic leader of the foreign office, who you may remember being described as being a minor obstacle because he did not get along with the Battle Captain.

Figure 13.1 shows a piece of the “Vatroslav Dossier” made available to players in the ALTSIM simulation. Writer Larry Tuch developed the dossier by summarizing the Vatroslav character bible, which he also created.

As diabolical as Dragon Vatroslav was as a villain, and as good as he was at articulating his genocidal point of view, he pales in comparison with other simulation scenario villains who do not have the clear criminal records or outspoken hatred of the United States. The screenwriter who created the character had come up with a far more sinister cast for the Final Flurry exercise. As Chapter Two points out, in that simulation participants played members of a national security advisory team making recommendations to the president on international matters at a time when every hot spot in the world had erupted at once. Leading the cast of villains in that exercise was the president of a Middle Eastern country who had been very well indoctrinated in the ways of the West. He appeared on a popular evening news magazine show and graciously accepted a New York Yankees baseball cap—his favorite team, he said. This warm-hearted interview was shown to the participants in the simulation as part of a news summary that was supposed to be prepared for them every day by the intelligence community. It so endeared him to many of the participants that they automatically decided he was a friend, a good guy, and later when he began taking a very active path on the road to war, the participants still thought that he was bluffing and at core he was really on their side.

If they had dug deep into the intel available to them, they would have learned that his father played a role in the first World Trade Center bombing and that he blamed the United States for the death of his father and the plight of his country. This deep-seated anger festered beneath the mantle of friendship that he put on if only to disguise his true intentions. This villain, who masks his intentions in the guise of friendship, offers the greatest challenge to participants in these types of simulations, especially if the writer is skilled enough to build a character who has the capacity to lie because he understands and even sympathizes with his enemies.

A VILLAIN’S INTERNAL CONFLICT

So far we’ve talked about those steely-eyed villains who know exactly what they want and how to get it. They may be duplicitous but their threat to the hero is clear and direct. The hero, facing self-doubt and trying hard to figure out the adversary, may have a rough go of it. But what if the villain is as conflicted and confused as the hero? What kind of a burden does that put on the hero? You would think that a person who rises to a position of power and has the ability to launch armies, attack cities, plan terrorism would end up being determined and single minded. But we know that is not always the case.

Figure 13.1 A sample ALTSIM character dossier.

Hector Cantu was an opportunistic and idealistic young man who found success in dealing with an international drug cartel. He considered himself a man of the people. The cartel gave him the opportunity to run for president of a Latin American country, if he would represent their interests as they instructed. He agreed, but once in power he found himself caught between the wishes of the cartel and the needs of the people. His erratic foreign policy began to threaten world interests. He popped up on the radar of the Final Flurry exercise and became yet another challenge for the participants. Of course, Cantu was really a creation of the screenwriter, and the man’s personal conflicts were designed to challenge even the finest statesmen-in-training. How could they figure out what Cantu would do next when even he didn’t know? When the great obstacle between the hero and the goal is a loose cannon with almost no predictable behaviors, the simulation gets more engrossing, more powerful, and more instructional. The key to creating this kind of character, again, is the character bible. What confused history lead to the kind of inconsistent decision making that makes national security nearly impossible? Is it really only in Cantu’s DNA, or is he just indecisive? It is in the best interest of the writer to take the behavioral approach and try to figure out a history that sets up and explains every action of the villain.

It may seem as if designing these deep character motivations and behavioral traits can only work in the high-stakes setting of a military or political conflict. However, similar motivations drive character behaviors in any sort of business, negotiation, managerial, or first-responder situation. Think about the drama, high stakes, and machiavellian behaviors we have all witnessed in the Enron and Tyco scandals, as well as the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Interestingly, complex character motivation and behavior exist in every walk of life, and conflict and high stress will inevitably bring these to the surface.

SUMMARY

Creating characters for simulation stories requires that the writers and designers explore their motivations, backgrounds, and complexities. This especially applies to the creation of villains who, in simulations, must represent the greatest obstacle to the goals of the hero. They must also be given the capability to challenge the skills of the hero in the areas that the simulation is trying to teach. The villain’s background must provide them with experiences that will motivate their actions: anger, deep hatred, bitterness. But these characteristics must also be balanced with a broad range of knowledge, understanding, and sympathy, all those things that allow people to act in unpredictable but internally consistent ways. A classic villain with a strong backstory provides a good adversary. A villain with internal conflicts makes the job of overcoming villainy even more difficult. And the educational story simulation may be at its best when it designs in features that make it possible for the hero’s own weaknesses to actually make him or her the villain as well as the hero.