15

The Instructor as Dungeon Master

The role of the simulation leader can be played out in a number of different ways in both military and industrial training simulations. In some cases leaders frequently take on the role of the opposition forces (the enemy or corporate competitors). In other cases the system operators become tacit but nevertheless highly visible system operators.

An example of the former case can be seen at the Army’s National Training Center in California, where live military maneuvers are held in the field. The leaders who portray the opposing forces actually participate in field maneuvers as the red team. These simulation leaders are so skilled and experienced that the student-soldiers seldom have a chance of winning the simulated encounters. One professional trainer dubbed such exercises, “learning by defeat.” Nevertheless, it is a strategy that has been followed successfully by the Army and by numerous corporate training organizations as well.

The following is an example of the latter kind of simulation management, in which the leaders are highly visible system operators. In the late 1990s, the US Army ran a series of military simulations at the National War College at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The simulations were part of an effort called Army After Next in which the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command attempted to anticipate the kinds of demands that the Army would be facing in the far future (circa 2025). The scenario for the game was built around a set of research objectives created in response to a request from the Army Chief of Staff. The political situations in the scenario were selected to provide a test bed in which the research objectives could be analyzed.

One such complex simulation dealt with an international crisis that was fomented by a dictator who established an independent state or a rogue nation that operated outside the bounds of international law. Participants in this simulation were divided into groups who played the leaders of all the nations involved in the crisis. Each nation group was called a cell and was identified by a different color that represented their geographic entity. The United States was represented by several cells, most notably the blue cell.

In this exercise the leaders of the simulation became the white cell, a controlling organism that ran the entire simulation. The white cell included game management and assessment personnel, an analysis team, a media production team and various content experts. The white cell monitored the progress of the participant groups through the exercise and modified the exercise to accommodate the unfolding events.

Every afternoon, members of the individual cells presented their decisions as a group. These presentations were monitored by assessors who, that evening, discussed them with the rest of the white cell. A chief assessor determined upcoming game events based on a reading of the actions and intent of the participant groups as weighed against the objectives of the game. Later that same night, the media team created new media elements to accommodate the previous day’s events, and to kick off activities for the next day.

Organizations such as the white cell are common in other military simulations as well. Often in simulated warfare, tactical military maneuvers are simulated by groups of officers who take on the roles of field commanders who must deploy virtual troops in response to simulated enemy activity. Again, the people running such simulations form white cells to monitor their game’s progress and adjust it in response to participant actions. They can see trends in the participants’ behavior and can predict outcomes. As such they can inject events that present unique training challenges or counter trends that will lead to less positive learning experiences.

As noted in previous chapters, managing the events of a simulation to lead to desired outcomes for pedagogical reasons is not exactly the same as pursuing dramatic goals. But it is similar. The reason for pursuing a dramatic goal might be to maintain the highest possible level of tension, or keep the simulation story and the characters’ actions consistent. Pedagogical goals might be to make certain that the participants have a learning experience that will teach them a particular lesson. Other pedagogical goals might seek to make sure that participants are in a position to deploy the desired assets in order to learn how those assets will operate in a specific environment. Leaders of most military simulation white cells don’t have a story to deal with, nor do they have the tools necessary to create, maintain, or modify a story. In a typical white cell scenario, for example, there may be some attention paid to the psychology of the enemy leaders but not the same kind of effort to detail the experiences of their youth and the shaping of their character that might lead them, in a moment of crisis, to issue some seemingly inconsistent directive that could have devastating effects on their cause. That kind of focus is the result of the creation of character bibles, which lead to more formal explorations of character and its effect on the shaping of events.

In these simulations little attention is paid to the creation of the arc of the story which seeks to ensure that there is rising tension throughout the experience. There is also little attention paid to the construction of a formal crisis moment just before the end of the simulation. It is at this moment when all the key performance goals are tested. Attending to the arc of the story helps simulation planners make sure that story elements are carefully placed so that they will all be available for the crisis moment.

In story based versions of these systems, the activities of the white cell will have to be guided by added design materials, media, and training that will enable members of the cell to complete these story-related tasks. The members of the cell will have to be aware of the dramatic elements present in the situation and know how to use them to enhance the power of the event. Moreover, in the best of all possible worlds, they will be able to construct new story elements that are consistent with the dramatic goals of the story and can influence the story in the most appropriate way.

Imagine a story-based simulation conducted in anticipation of the final days of World War II, one that was so well crafted that it could have anticipated the inexplicable decisions that Adolph Hitler made as allied armies advanced on Berlin. Seems impossible, doesn’t it? And yet only a story-based simulation would have suggested that such bizarre decisions and events were ever possible. In other words, white cell guided simulations can become more powerful, more memorable and can gain instructional value by adding a well-crafted Hollywood story to the effort.

Having suggested that adding story-based elements to these large-scale training simulations could be of great value, the question then becomes how to provide the white cell with the kind of support and information they need to enable them to introduce, maintain, and enhance the story without making the effort seem unwieldy and irrelevant.

The tools needed to allow a large-scale simulation white cell to create and manage a story-based simulation are similar to those we have been describing in previous chapters when we talked about the role of the instructor in the Final Flurry, ALTSIM, and Leaders simulations. And the model for all those activities comes from role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons. In D&D, as you may remember, it is players’ job to construct their characters and make decisions for them as they move throughout the fantasy world. But it is the Dungeon Master (DM) who provides the context and the consequences of actions. You make the decisions, but the DM tells you what happens as a result of your decisions. In the finest sense of the role, the DM is a classical storyteller.

You’ve chosen this character, you’ve amassed these weapons and these strengths, and now you choose to go down this corridor in order to confront and kill the Giant Spider. You know what the Giant Spider is capable of, you know its strengths and weaknesses, but at the moment of truth it is the DM who decides the most exciting way that the spider confronts you. In its finest sense your battle with the Giant Spider is collaborative story telling with both you and the DM using one great storytelling trick after another to gain the advantage.

The instructor who is controlling the activity in a military simulation has a myriad of roles to fill. He or she must make sure:

• |

The system is running properly. The participants are staying within the bounds and rules of the simulation structure. |

• |

The simulation story stays on track. |

• |

The story stays internally consistent. |

• |

The participants receive the appropriate feedback for each of the critical decisions. |

• |

The simulation follows a path that will assure the participants of gaining the highest-level educational experience. |

If necessary, the instructor must be ready to create content that will support and enhance the dramatic goals of the simulation.

In Final Flurry, the instructor monitored the classroom discussions of the student participants who were trying to deal with a world in which everything was going to hell at the same moment. The instructor had to feed them content as the simulation progressed. The instructor, in fact, chose the content that would lead the participants in the appropriate direction required by the goals of the simulation. If necessary, the instructor also created content that would help maintain the veracity of the story and provide specific feedback needed to keep the reality of the simulation intact. For example, if the participants made recommendations to the National Security Advisor about points that the president should make in his speech to the nation that night, then it was the instructor’s responsibility to review the content, select matching prerecorded responses, and if no response matched some recommendations, to create content and send an e-mail back to the participants explaining why the president did not make that point (see Chapter Two).

In ALTSIM, it was the instructor’s job to monitor the flow of content from the automated simulation system to the participants, and to select additional pieces of optional content to send when it became clear that those pieces of content were not understood or put to proper use. Moreover, in ALTSIM—a system that simulated an entire communication network—the instructor could choose among a variety of media: video clips, text messages, audio that screamed out of the participants’ computers like frantic messages screaming out of the loudspeaker system in a real tactical operations center, etc. Again, the instructor could create content to reinforce messages in the form of e-mails, voice calls, or video command messages delivered by a simulated character.

In both cases the instructor was acting as a techno-wizard impresario, orchestrating the simulation event, adding interpretation when needed, and creating compelling content when it was absolutely necessary. In this way too, the instructor was acting as a Dungeon Master.

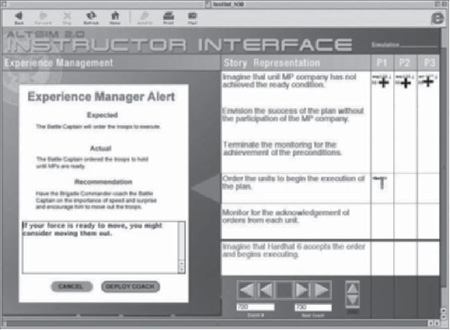

Figure 15.1 The ALTSIM Instructor Interface, which tells the woman or man in the loop when to intervene in the simulation and even what kind of content to create.

The ALTSIM system went very far to automate the system, in that it prepared many alternate messages in every form of media. Its Experience Manager monitored the activities of the participant and recommended interventions when it appeared that the participants were getting off track (see Chapter Ten). But all these were presented to the instructor for approval, and the instructor was always given the option to create additional content that he or she thought would provide better or more targeted feedback to the participants.

What all this means is that the authors of the Final Flurry and ALTSIM simulations constructed systems that were flexible enough to allow instructors to play a major role in the implementation of the exercise. The tools that were created by the simulation authors built in processes for instructor approval of pre-written media elements and allowed for the creation of original content by the instructor, in a variety of media, when that content was necessary.

ALTSIM (though it was built to use a man in the loop) did not require it. That is, the methodology that sent content to the instructor for approval before sending it to the participants could be overridden so that the simulation would, in fact, send information directly to the participants. ALTSIM could be totally self-sufficient. In doing so, however, it had to sacrifice the benefits of original content creation. A fully automated ALTSIM had to rely solely on content created before the simulation began and which anticipated as best it could the activities of the participants.

The Leaders project followed a similar course. It was constructed entirely as a branching storyline where all content had already been created. The role assigned to the instructor then was that of a mentor, who monitored student progress and only participated in the simulation when he or she interrupted the exercise because the participants had gotten so far off track that instructor participation became mandatory. Such approaches place heavier burdens on the creators of the original content to anticipate the actions and decisions of the participants. They give up a great deal in dispensing with the custom-tailored, high storytelling craft of our new age Dungeon Masters. Nevertheless, they anticipate and lead the way for the automated Dungeon Master, white cell, and automated story generation systems of the future. Nevertheless, while the creation of the automated Dungeon Master is a great research problem, for those constructing simulations that are not purely research oriented, it’s clear that participants learn more when a live instructor or game manager is built into the system.

SUMMARY

There are a number of different approaches to the management of simulation games. Leaders can run simulation by taking on the role of the opposing forces, or they can become highly visible system operators who manage the events of the simulation in order to achieve pedagogical goals (the white cell).

This role gets far more complex in managing story-based simulations. Managers of story-based simulations play roles similar to those of classic Dungeon Masters, who are actually participant storytellers. These leaders must be able to select appropriate content to respond to user actions and even create content tailor-made to respond to unique participant actions. But all of this must be done with an eye on the dramatic as well as the pedagogical goals of the simulation.

Automated leadership systems for story-based simulations will actually have to be able to generate story elements synthetically, if they are to rival the powers of the current “man in the loop” simulation management systems.