21

Immersive Desktop Experiences

A primary rule of learning simulation design is that the simulation should focus on the behavior to be learned and give adequate feedback to the participants as they progress through the simulation experience. While that should seem obvious, there is a real danger in creating simulations that spend enormous amounts of time, energy, and money faithfully replicating parts of the environment that have no bearing on the learning experience at all.

Often, faithful replication of irrelevant parts of the environment actually detracts from learning, because the learners focus on the details of the environment and as a result ignore the specific behaviors that they are attempting to master.

For example, military simulations that focus on an exact reconstruction of a command center or of part of a vehicle often add elements to the simulation that get in the way of learning. Trying to make gauges and knobs and control levers look exactly like those in the latest version of something may make participants ask, “Why is that control just slightly different than the one I’m used to? Why has it changed? Are the newer models better, and if so why?”

This is truly inappropriate when the behavior to be learned has very little to do with the operation of controls and more with the reading, interpreting, and understanding of the messages being delivered by the information system.

In training for high-performance skills, Human-Machine Systems engineer Alex Kirlik commented on a distracting effect of the anti-aircraft warfare coordinator station (AAWC) at a naval training center and noted: “The field study thus revealed that the need for the trainee to attend continuously to the console manipulation activities severely compromised his or her ability to attend and benefit from the tactical decision-making and team coordination experiences that were the stated focus of training” (Kirlik et al., Making Decisions Under Stress).

Focusing on the behavior to be learned rather than the exact appearance of the environment itself will help prevent this kind of mistake. For this reason the abstract elements that go into skills like crisis decision making seem ideally suited for computer based simulations, in which many of the decision elements would normally be delivered by a computer.

But what happens when the environment that is being simulated has elements that are necessary to the skill being taught, but that cannot possibly be built into the physical environment?

Hopefully, the answer is in the media.

If you think of the physical environment as just another medium that presents information to the participants, then a physical object in the real world can be simulated by a cleverly designed piece of media that will do the same thing.

SQUEEZING THE ENVIRONMENT INTO THE COMPUTER

In the Advanced Leadership Training Simulation (ALTSIM), we faced the problem of trying to replicate the experience of being a member of a team within a Tactical Operations Center, but with participants who were geographically separate and operating in environments that looked and sounded nothing like a real TOC.

Our answer was to try and build as much of the experience as possible into the computer, letting the computer actually play the role of some of the physical elements in the TOC environment.

For example, the Significant Activities Board (SigActs Board) is a huge white board that hangs in most TOCs. On it, each battle captain provides a list of the most important events that happen on his or her shift. The events list forms a kind of background for the decisions that have to be made during the day.

In a distributed learning situation you lose the great value of having one big board looming over everyone as they go about their daily business. And you take away the valuable behavior and group dynamic that comes with having that board there to provoke discussion and arrange information. Nevertheless, the SigActs Board can be replicated on the computer screen. But the interface must provide easy access to it, so that every member of the virtual team can keep an eye on it as events unfold, and one member of the team can have the primary responsibility of keeping it up to date.

The design task, then, is to provide the proper user interface design so that the SigActs Board maintains its prominent position and role in the virtual environment and does not just fade away from lack of use or presence.

In an environment like a TOC, as important as the presence of the SigActs Board may be, the need for audio participation is far more important. In fact it could be argued that one of the key decision-making skills to be learned in crisis decision making is the ability to communicate verbally. For that reason, direct voice communication between the participants was considered critical to the design of ALTSIM. Participants had to be able to talk to each other across the world in order to simulate the enclosed group decision-making process of the TOC. We went a step further and employed Webcams so that the participants could see each other face to face as they rolled through the decision-making process. Again, in a TOC, they would normally be together and would see each other.

While we felt that direct voice communications was a major factor in group decision making, an equally important factor was the distribution of various kinds of information to the working members of the staff.

In a real TOC, there is often a television set up in the corner of the room showing the latest CNN or other news broadcast. At the same time, direct radio communications are fed into the loudspeaker system so that there is constant radio chatter. There is a barrage of e-mail flowing into the different computer workstations as well as a vast network of information available for deep research.

We took the daring and dangerous step of trying to integrate all these disparate elements into a single interface that we hypothesized as a future military information network designed especially for participants in a TOC. The danger came from the fact that building such a system might make the participants dependent on its structure and actually weaken their skills. The upside of the approach was that such a system could allow participants to focus more clearly on the elements of decision making, while we had greater control of the variables, including the amount of distractions in the environment. We attempted, in fact, to focus on the actual behavior that the simulation was supposed to teach.

We gave the ALTSIM system a simulated news network that played on the computer screen. We piped audio through the computer as though it were the streaming chatter of a TOC. We customized the flow of information so that specific information would go to people in specific roles and we maximized the use of media so that each element of information was presented by the medium that was most suited to it. E-mail reports often had video or still attachments to make a specific point about the current situation. When the Battle Captain called for aerial surveillance, streaming video fed back selected shots of the appropriate area. If he or she asked to speak to a commander in the field, we often delivered picture phone access to the individual.

Traditional e-mail delivered updates and reports on events as they evolved, and when things got urgent, radio messages from the battlefield came in loud and clear. The system not only contained the latest maps, but they were interactive and updatable, so that the assigned member of the team could modify the central display that was seen on everyone’s computer. Urgent Messaging allowed an officer, at the Battle Captain’s request, to send messages to the simulated actors everywhere in the simulation: higher-ups, adversaries, and allies alike. Needless to say, this input prompted the interactive responses of the system, and feedback again was often in the form of mixed media delivered according to two rules: (1) what was the most typical way that the response would normally be delivered, and (2) what was the most clear-cut and compelling way to make the information stick.

Interestingly, the same method that provided such strong relevant message delivery to the participants also enabled us to deliver strong distractions so that irrelevant or contradictory data, if we chose to employ it, could be presented with the same strength as the most critical information.

The entire system was geared to give the instructor the most powerful tools possible to present all manner of information in response to participant action or inaction.

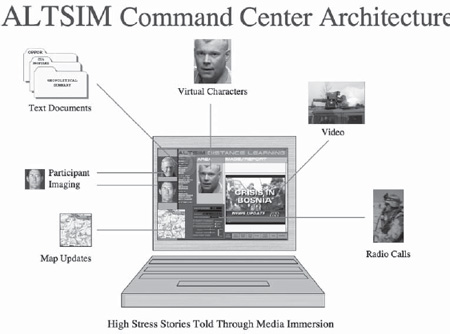

The intent was to create the most highly fluid, and yet most highly controlled crisis decision-making learning environment possible. Figure 21.1 illustrates the media mix that was used to create the virtual TOC on the ALTSIM computers.

In the end, the carefully chosen mix of media allowed us to focus on the actual decision-making elements required by our learning objectives and deliver them exclusively through a computer-based, distance-learning network.

ALTSIM was created for the US Army, but simulations on topics from stock trading to disaster relief to urban traffic management scenarios could be created using LANs or WANs. Video assets can provide on-the-scene representations of newscasts, audio assets can replicate first responder communiqués, and Flash animations or macro-programmed spreadsheets can replicate real-time data updates.

Figure 21.1 ALTSIM interface screen showing the contributing media elements.

Clearly, low-cost technologies like intranet instant messaging and push-to-talk radio/cellphone technology can also be deployed to achieve an immersive desktop experience.

Further advantages to delivery on a LAN or WAN include (1) the data security the contained environment should offer, and (2) the relatively homogenous software and hardware environment that should be available. As we’ll see in our next chapter on Internet delivery, these issues must be considered before media and platform are locked down.

SUMMARY

When building simulation experiences, worrying about the bells and whistles that go into the surrounding environment is a waste of time and money. Because of this, using computer systems to simulate critical behaviors can work for a variety of skills. However, there are elements in the physical environment that bear on the behaviors to be learned, and finding ways to integrate them into a computer-based system is a challenging but important task.

Matching the medium to the message allows designers to deliver critical information in the most effective way possible. It also allows for the controlled introduction of complexity and noise into the environment and can enable and reinforce effective communication as a means of collaborative problem solving.

ALTSIM was unique in that it did not attempt to recreate the TOC environment it was simulating. Instead, it sought to build a new, streamlined, decision-making system that enabled participants in distant parts of the world to work together to hone their skills. The intent was to focus on the presentation of the facts essential to understanding the situation and the communication process that was needed to execute the final decision. The same system allowed an instructor fine control of the balance of relevant and irrelevant data, and the ability to inject conflicting information that might add challenge to the task.