Questions are the answer

This is a chapter about questions – how to handle questions from participants and how to ask questions that make a positive difference. You may have some questions about questions:

- Why are questions so important?

- What is the best way of handling tricky questions?

- To what extent should I use questions to test knowledge?

- How can I use a question from an individual to help group learning?

- What questions can I ask to promote thought and encourage learning?

- What is a good process to follow when someone asks a question?

Jeremy remembers being on a personal development course in the 1990s and the trainer used the phrase ‘questions are the answer’. It resonated with him and this approach is critical in non-directive coaching as well as business training. Voltaire once wrote: ‘Judge a person by their questions, rather than their answers.’ Great questioning is always at the heart of outstanding teaching, learning and information exchange. We know that among the goals of training are to improve knowledge and change behaviour and we cannot do this solely through lecturing. If you want to be a real bore, just lecture. Why? Many people have issues with authority figures and therefore may discount much of what you say, even if you build a strong connection. Secondly, lecturing keeps the audience in a passive listening mode. Questions change a person’s brain from a passive to active mode – it is the simplest engagement tool around. Questions help people learn, encourage thought, build relationships, avoid misunderstandings, develop awareness and encourage responsibility. As Tony Robbins, the great motivational trainer and coach wrote: ‘Successful people ask better questions, and as a result, they get better answers.’

Engaging the audience through questions

Let us focus first on what does not work.

You will know the difference between open and closed questions. Most of the time we will use open questions when we train a group. Closed questions have a bad press with trainers and you can understand why. Closed questions are often driven from assumption, can be leading, and are focused on getting agreement or seeking clarification, rather than developing thought. If at all possible avoid closed questions such as: ‘Can anyone tell me?’, ‘Can you remember what we covered in the last session?’, ‘Does everyone understand?’ These are examples of questions a primary school teacher might use. They are not adult to adult questions. We want to avoid the participants becoming tense, uneasy or feeling silly.

Never use questions to embarrass or intimidate. Our task as trainers is to encourage, build up, impart knowledge and aid learning – never to tear down, discourage or abuse. If we use questions to demonstrate how much we know, to put a participant in their place or to establish our authority, we are probably revealing our own issues to the group. You might need to pose questions which are testing knowledge in certain types of training. However, be careful about overuse. What if you test knowledge and it is not there ... how does the participant feel? Overdone, you might appear patronising and you will risk creating tension, and unnecessary competition. Finally, avoid questions that begin with a ‘Why?’ These questions are backward looking, resulting in a justification rather than a more objective, forward looking response. Again they can provoke a childlike response in the audience. Do you remember when a parent said to you ‘Why did you do that?’ It does not make you feel good. Use questions as a surgeon might use a set of surgical knives. Each type of question has its particular purpose, each is capable of good work when used effectively, yet each is also capable of pain, mayhem and scar tissue when used improperly. Well-trained hands using questions as sharp scalpels in the right places is our objective, rather than ill-trained hands using blunt instruments or axes.

The right questions from the trainer help understanding, enhance interest and increase learning. You can set the scene for this in the first hour. Mention that you will take questions at any time and also put up a questions board and regularly ask participants to contribute with sticky notes. Then you may decide to ask questions in your set-up of the day (use the COMB, see Chapter 11 for more information). They can be used as a mini needs analysis to get to know the group if necessary and identify what is important to the individuals and, collectively, the group. This approach can stop you making erroneous assumptions about your audience and may also help participants feel less awkward about their level of expertise and more comfortable about how the session will go. Asking questions is a great way of building a connection, motivating and relaxing the audience. Here are three examples of the sort of questions you might ask the audience for three different training scenarios:

Questions come in different shapes and sizes. Listed below are some of the more useful ones to use, some tips about how to use them and some examples.

Rhetorical questions

Definition

Rhetorical questions are not direct questions, in that they do not expect an answer. They are really just statements phrased in question form. By posing a rhetorical question your audience have to start thinking about the answer.

When to use them

Using a rhetorical question has many positive psychological benefits. First, it engages and directs the group. It forces the audience to participate mentally by creating a hypothesis/resolution situation. Once a participant hears a question, they mentally start trying to answer it by formulating a hypothesis about the answer. This is resolved when it is immediately answered by the presenter, which gives the audience the solution (resolution). This is mental participation. Rhetorical questions can also demonstrate shared experience, work on the unconscious and draw the audience to agreement. They can be a good way of opening a training session or to start a sub-section. They have far more impact than a bland statement and will start to get your audience thinking and make individuals listen to what you have to say.

TIPS

- Rhetorical questions are even more powerful if you use a string of them.

- Pause after you have asked the question to let it sink in – you may then decide to answer your own question

- Pepper them throughout you session.

- They are good to use after breaks.

Examples

- Why should you use xxxx?

- How much money did you waste from your budget last year?

- What is the one issue we see time and time again?

- What will it take, I wonder, for things to change soon?

- When x occurs what can we do?

Experience-based questions

Definition

Questions which draw out the experience of the individuals in the room.

TIPS

- Identify your outcome – what experience are you seeking to draw out that will help the group?

- Avoid asking individuals directly until you have earned the right through establishing credibility and connection.

Examples

- What has worked for you so far?

- What examples fit the pattern?

- How much do you know about ...?

- What qualities do you think are essential for this to work?

- What challenges have you faced?

Opinion-based questions

Definition

Used to elicit an opinion or value judgement. There can be no wrong answers to these questions, since an opinion does not require any basis in fact.

TIPS

You need to steer a careful path here between eliciting opinions and the whole session becoming derailed because the opinions undermine what you are teaching. For example, if you are teaching professionals (lawyers, accountants, doctors, etc.) they will have very strong opinions on a range of subjects and they can hijack proceedings.

Examples

- What do you think?

- What is your view?

- Who believes something different?

- What would be an alternative viewpoint?

Testing questions

Definition

To test learning.

TIPS

- Testing questions can seem patronising to adults. Think carefully about whether they are required.

- If you need to use test questions, be creative. For example: create a circle and get participants to throw a ball to one another and ask a question at the same time.

- Rather than pick on individuals, do a team quiz on tables.

Examples

- As you think about what we have covered, who can remember ...?

Careful listening

There are other times during a training session when you will ask questions. For example, to the group at the end of an exercise to identify what has been learned, to a specific individual and at the end of the session during the action planning stage when you are helping them identify what they are going to do as a result of attending. In whatever training scenario, make sure that you give the person you are questioning or the group enough thinking time. Avoid interpreting a pause as a ‘No comment’ and ploughing on. Skilful questioning needs to be matched by careful listening so that you understand what people really mean with their answers. Your body language and tone of voice can also play a part in the answers you get when you ask questions. Look as though you really want to hear the comments. Your job here is to facilitate thinking and elicit responses to support the learning.

How to answer questions from the group

How do you handle questions that get fired at you as the trainer? This is where you will earn your crust. You need to know about how to prepare, how to stay in a resourceful state and how to answer any question. Questions from the audience can make or break your credibility. We have met trainers who fear questions and you may be out of your comfort zone when you get questions. However, the ability to ask questions is a sign of a curious mind and the mark of a good learner, so we need to do everything we can to encourage questions and then answer them effectively. Many people in your audience will believe that asking too many questions is a sign of stupidity and trainers need to break that unhelpful belief by encouraging questions from the start and throughout a session.

A great way to plan any business training is to ask yourself: ‘If I was in the audience’s shoes, what questions would I ask?’ Then build your session around these questions. For tough audiences we often consider the most difficult questions we really do not want to be asked and then decide how to answer them, in case they crop up. If you can answer these ones easily, then all other questions will be straightforward. If you are training as part of a team, decide who is going to handle which questions. To ensure cohesion you may choose to filter all questions through the team leader. Finally, decide when and how you are going to take questions – in most business training, questions are taken throughout the session.

Questions you get may be tough and you may not be able to answer them immediately. If you start getting nervous or demonstrate that you are uncomfortable you will undermine your own credibility. So you really need to listen to the question, ensure you continue to diaphragmatically breathe and (literally) keep your head up (see Chapter 14 for more information). Smile, retain eye contact and, if you need to, find a way to think before you answer.

The 4A model for handling questions

Here is the process we teach trainers to use when answering questions: the 4A model. It can be used whenever you get a question from an individual or from a small group, or as a result of an exercise. It has four steps:

- Acknowledge

- Audience

- Answer

- Ask.

Here is more detail on each step.

Step 1: acknowledge

Remain silent, listen carefully and ensure that you understand the question. Treat all questions equally and without judgement. Never make anyone feel ‘wrong’. Acknowledge the individual who has asked the question. This may be a simple ‘Thanks for that question John’. However, you may need to ask the person to rephrase it if it appears convoluted or comes out as a statement and to a large audience we recommend you repeat the question. Some may not have heard the original.

Step 2: audience

If appropriate, allow the questioner or someone from the audience to answer the question. This gives you time to think and it may well be that an audience member can answer it perfectly well. This works less well with large groups. You might say ‘That’s an interesting question, what do you think?’

Step 3: answer

Avoid a long diatribe and if you have already covered the question, avoid the sarcastic ‘Well, we looked at that an hour ago’ response. Maybe you were not clear enough and further explanation is required. We do not recommend the bridging technique so beloved of politicians when they are answering questions from journalists. For example: ‘That’s an interesting issue but what the public are most concerned about is ...’ or ‘Some say that and what our research shows is ...’.

The public is fed up with this approach and it tends to undermine trust in politicians. It is best to answer the question head on. Keep to a maximum of three points and spend a maximum of two minutes answering. If you can be certain of the answer and the questioner is looking for certainty, then provide certainty. However, in many cases you will position your answer as just one option and seek ideas from the rest of the group after you have spoken. You do not necessarily have a monopoly on the truth.

Step 4: ask

Go back to the person who has asked the question and check that it has been answered satisfactorily. A simple ‘Does that answer your question?’ will suffice. Be sure to ask and to respond if they answer negatively. If someone answers your question with a ‘Not really’ then you need to probe to find out what else they might need and start the process from ‘acknowledge’. Not doing this can undermine credibility and trust.

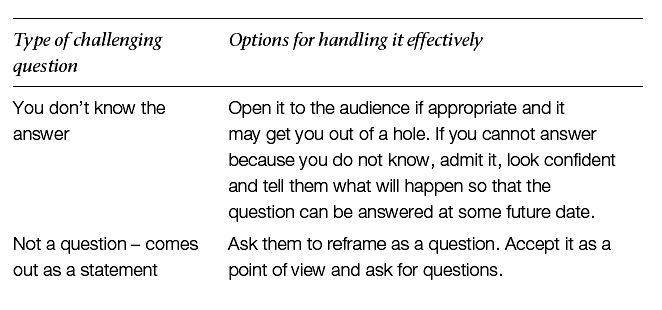

Options for handling different types of questions

Not all questions will be straightforward to answer. You are going to be challenged and it is useful to get a sense of what to do when faced with these challenges. Here is a table which includes some options for you to increase your flexibility.

Summary

This chapter has focused on both how to use questions as a way of engaging the audience and how to answer questions generated from individuals in the group. Just lecturing from the front will never be enough nowadays to educate, persuade or motivate. The questions you pose as the trainer will form part of the engagement process and you will increase your credibility and help trainees integrate the learning when you handle questions with aplomb.

- In the first section of this chapter we identified:

- that it is best to avoid closed questions;

- intimidating or embarrassing people with direct questions should be avoided;

- the reasons why some questions rarely work well;

- that questions at the beginning of the training can form a strong connection and act as a mini needs analysis for the group.

- The types of question you have at your disposal include rhetorical, experience-based, opinion-based and testing.

- The trainers who cope with questions the best typically prepare assiduously and remain in a positive state when they are faced with a question.

- The process we recommend to answer a question is the 4A model: acknowledge the questioner, throw the question open to the audience if possible, answer the question, keeping the answer simple and using three key points as a maximum, and ask the questioner whether the question has been answered satisfactorily.

- Finally we offered some options when you are faced with tough questions.

We leave you with a quote from Lao Tzu, the Taoist philosopher, which encapsulates the best way to both encourage and handle questions from those who want to learn:

The novice teacher shows and tells incessantly; the wise teacher listens, prods, challenges, and refuses to give the right answer.