How to evaluate training effectively

Let’s begin with a very basic question: what do we mean by evaluation? The answer is in the word – it is about value – ascertaining the value of, in this case, business training. So evaluating training focuses on identifying and judging the value of any formal development programme that has a face-to-face training event as part of its framework. So where does the value reside? The value of any training initiative will focus on how useful it has been in relation to:

- an individual who has experienced the training;

- the impact that individual, with an improved knowledge and capability, has made to a specific job role or team;

- the wider impact on the business (maybe in terms of improved process or increased profitability).

So, let us start with some key questions. Fred Nickols, (a well-known US expert on planning, executing and evaluating) who has contributed much to our understanding of what is practical and sensible asked these questions about evaluating back in the early 1990s:

Evaluate? Evaluate what? Training? What do we mean by training? What’s to be evaluated? A particular course? The trainees? The trainers? The training department? A certain set of training materials? Training in general?

More to the point, why evaluate it? Do we wish to gauge its effectiveness, that is, to see if it works? If so, what is it supposed to do? Change behaviour? Shape attitudes? Improve job performance? Reduce defects? Increase sales? Enhance quality?

What about efficiency? How much time does the training consume? Can it be shortened? Can we make do with on-the-job training or can we completely eliminate training by substituting job aids instead?

What does it cost? Whatever it costs, is it worth it? Who says? On what basis? What are we trying to find out? For whom?’

(‘There is no “cookbook” approach’, Evaluating Training, 2003)

These are some of the killer questions that need to be asked when we think of our evaluation strategy in an organisation. Our strong suggestion is that the focus of evaluation should be about identifying the extent to which the learning has been transferred to the workplace. So ultimately we are looking at levels 3 and 4 of the Kirkpatrick model, which we will be discussing in this chapter. The reality in most training or learning and development (L&D) departments is that there is only capacity to properly evaluate key courses. The issue is that typically even the meaty, strategic and most expensive programmes in organisations are not evaluated very successfully, or worse, completely superficially.

The main reasons to evaluate are:

- To determine if the original diagnosis was correct and that we are looking to correct, change or develop the right things to achieve the business outcomes. It is a source of data and feedback which will also help determine whether the programme will be run again.

- So that we can justify ourselves internally. Training budgets can too easily be cut if there is no evidence that training works to improve business results.

- Get us a seat at the top table. If we can prove the efficacy of our training in measurable terms (not necessarily ROI) we are more likely to improve the influence of the training/L&D function.

We all know that when money is tight, training budgets are amongst the first to be sacrificed. If there is thorough, quantitative analysis then training departments can make the case necessary to resist these cuts.

Training is one of many actions that an organisation can take to improve its performance and profitability. Only if training is properly evaluated can it be compared against these other methods and be selected either in preference to or in combination with other methods.

Consider also that the business environment is never standing still. Technology, the competition, legislation and regulations are forever changing. What was a successful training programme yesterday may not be a cost-effective programme tomorrow. Being able to measure results will help you adapt to such changing circumstances.

Training programmes should be continuously improved to guarantee better value and increased benefits for an organisation. Without formal evaluation, the basis for changes can only be subjective and therefore more open to scrutiny. These days there are many alternative approaches available to training departments, including a variety of on-the-job and self-study methods. Using comparative evaluation techniques, organisations can make rational decisions about the methods to employ.

Of course there are many barriers to evaluation, some of which have been identified in the previous chapter. If we can overcome resource issues, intransigence and cultural interferences there are some real benefits to effective evaluation:

- higher motivation of participants because you can demonstrate the value of a programme;

- proof that training makes a difference (examples may include productivity increases, cost savings, increased sales, improved retention of staff, greater team cohesion and morale, better messaging and clarity when presenting, reduced duplication of effort, less time spent correcting mistakes, a reduction in bad debts or faster access to information);

- increased investment from organisations because they can see the value that training brings;

- improved allocation of resources in future;

- higher profile of trainers and the L&D department;

- encourages and proves that change and improved results in the workplace can occur.

So, what are the pitfalls we need to avoid? What model should we adopt? What specifics should we focus on? What ideas are out there that work best?

The Kirkpatrick evaluation model

There is a good chance that you evaluate your training in some way – almost all organisations do. There are a number of different evaluation models that organisations use and you may well be familiar with some of them. We use a model that is called the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation.

Donald Kirkpatrick (Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin where he achieved his MBA and PhD) has just retired. His legacy is the evaluation model that was first introduced in 1959 and subsequently honed and sold to the training world, until he handed over to his son. He was president of the American Society for Training and Development (ASTD) from 1975, has written several significant books about training and evaluation, and worked successfully with some of the world’s largest corporations.

In assessing how best to address this topic we looked at a variety of models and kept on coming back to a central question – why not Kirkpatrick? His theory and evaluation model have now become the most widely used and popular model for the evaluation of training and learning and it is now recognised as an industry standard across the HR and training communities. Kirkpatrick is, in our estimation, the best we have right now. While Kirkpatrick’s model is not the only one of its type, for most business training applications it is quite sufficient. Most organisations would be absolutely thrilled if 25% of their training and learning evaluation, and thereby their on-going people-development, was planned and managed according to Kirkpatrick’s model.

The issue typically is that organisations are not using all the levels on his model and often only pay lip service to the idea of evaluation. So it is not that the model is wrong, it is the way we use it. As Kirkpatrick describes in a white paper available on his website (www.kirkpatrickpartners.com):

Most learning professionals have heard of the four levels, and many can recite them. But relatively few know how to effectively get beyond Level 2.

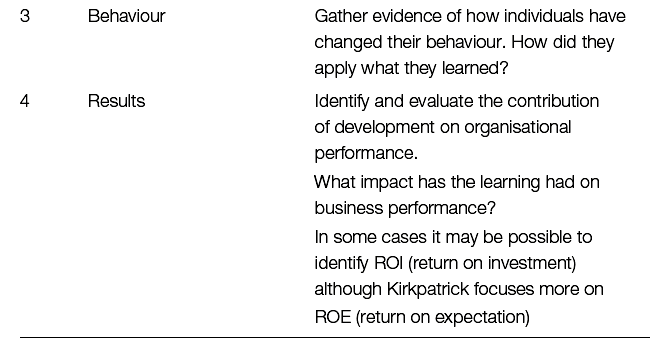

You may not be familiar with the model so the following table identifies the four different levels and the purpose of evaluating a training programme at these four levels.

Source: Based on Kirkpatrick, Donald L. and Kirkpatrick James D. (1994) Evaluating Training Programs: the four levels, Barrett–Koehler.

Anyone who has attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of any training initiative will know that as we move from level 1 to level 4, the evaluation process becomes both more difficult and time-consuming. On the upside, however, the higher the level, the more significant the value to the organisation. Perhaps the most frequently used measurement is level 1 because it is the easiest to measure. However, it provides the least valuable data. Measuring results that affect the organisation is more difficult and is conducted less frequently. In an ideal world, and especially with major or strategic initiatives, each level should be used to provide a cross set of data for measuring the efficacy of a key training programme.

The Kirkpatrick model in more detail

Level 1 – Reaction

Evaluation at the first level measures how those who participate in the programme react to it. Most organisations now (estimated to be about 90% by the Kite organisation) use what most people call ‘happy sheets’ to identify the initial reaction to a seminar, whether it is an hour’s lunch and learn or a three-day leadership programme. Typically they are either done as the last task at the end of the programme or within a couple of days, often online.

Participants are typically asked a range of questions focused on these areas:

- the logistics;

- the trainer – presentation, subject matter expertise and engagement with the audience;

- the value of the specific content, section by section;

- the relevance of the programme content to their specific job;

- how they plan to use their new skills back on the job.

There is a lot of cynicism about happy sheets and for good reason. If there is a strong connection between the trainer and the participants, or if the last session has gone particularly well, or if the trainer is hovering over the participants as they complete the questionnaire, the reactions are likely to be more positive. However there are many reasons for retaining them. They are quick, cheap, give you an immediate snapshot of what people think and feel and are sometimes anonymous, which allows people to be more honest and indicates to participants a positive and open customer service attitude. They also help the trainer to determine trends immediately. However, we need to remember that happy sheets can be rather superficial, subjective and influenced by many variables, often around an unwillingness to hurt the trainer’s feelings. We know of many organisations that only evaluate to this level and use it as a key measure of ‘success’!

Level 2 – Learning

This can be defined as the extent to which participants adopt a different mind-set, improve knowledge and increase skill as a result of attending. Measuring the learning that takes place is important in order to validate the agreed learning objectives. This level addresses the question: ‘Did the participants learn anything?’ The post-testing is only valid when combined with pre-testing, so that you can differentiate between what they already knew prior to training and what they actually learned during the training.

Evaluating the learning that has taken place typically focuses on questions such as:

- What knowledge was acquired?

- What skills were developed or enhanced?

- What attitudes were changed?

Measurements at level 2 might indicate whether a programme’s instructional methods are effective or ineffective, but it will not prove if the newly acquired skills are now being used back in the work environment.

Level 3 – Behaviour

If you are able to evaluate to level 3, it means you are identifying the extent to which a change in behaviour on the job has occurred as a direct result of the participants attending the training programme. This evaluation involves testing the participants’ capabilities to perform learned skills back on the job. Level 3 evaluations can be performed formally (testing) or informally (observation). The simple question here is: ‘Do people use their newly acquired skills, attitudes or knowledge on the job?’ It is important to measure behaviour because the primary purpose of training is to improve results by changing behaviour. So this is the level in which learning transfer meets evaluation. New learning is no good to an organisation unless the participants actually use the new skills, attitudes or knowledge in their work activities. Since level 3 measurements must take place after the learners have returned to their jobs, the actual level 3 measurements will typically involve someone closely involved with the learner, such as a supervisor or direct line manager. It can of course be verified by an objective third party. Although it takes more effort to collect such data than it does to collect data during training, the value of such data is important to both the training department and organisation. Behaviour data provide insight into the transfer of learning from the classroom to the work environment and the barriers encountered when attempting to implement the new techniques, tools and knowledge. They also have a real impact on what colleagues and managers think about the effectiveness of training.

Level 4 – Results

This level is concerned with the impact (the results) of the programme on the wider community. It answers the questions: ‘What impact has the training achieved?’ and ‘Is it working and yielding value for the organisation?’

In Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels (2006, Berrett-Koehler), Donald Kirkpatrick writes:

Trainers must begin with desired results and then determine what behaviour is needed to accomplish them. Then trainers must determine the attitudes, knowledge, and skills that are necessary to bring about the desired behaviour(s). The final challenge is to present the training programme in a way that enables the participants not only to learn what they need to know but also to react favourably to the programme.

The impact here could be identified in monetary terms (what is often described as ROI, the net financial gain set against the total cost). There are many situations in which a cost/benefit analysis is done in business and there are some occasions when ROI is possible and the right thing to do. Many organisations are now more interested in the ROI – the difficulty comes in identifying which programmes can fit the model and give an organisation a true ROI figure.

We have run sales or fee negotiation programmes when it has been possible to isolate a financial ROI although typically we have to factor in other influences. Most programmes cannot easily identify a financial ROI.

A perfectly sensible argument anyway is that business results are not the responsibility of training. They are both outside of our control (we could succeed in training a skill effectively but the market could change) and ultimately the responsibility of the business and its leaders – not just ours in isolation. Other managers have a role in delivering success and our responsibility is to be clear with the business leadership what skills, knowledge or behaviours they require and then to ensure we deliver these and check that they are being transferred. If we are delivering these skills, etc. but they are not delivering results then we have a different issue. Maybe key stakeholders are focusing on the wrong skills and processes to improve. The ideal approach is that key business stakeholders have a responsibility to define clearly what change they want to bring about and we should be accountable (jointly), through the training programme, for delivering that change. Whether it brings results is down to leaders being clear and correct in the first place.

If you put yourself in the shoes of a CEO, would you want ROI in an ideal world? Of course you would. It would be generally accepted that companies need accurate measures of ROI, if at all possible, for this is what will guide their human capital investment decisions. However, researched evidence suggests isolating ROI and proving its links to training is very tough. A study done by Ann Bartle (the Merrill Lynch Professor of Workforce Transformation at Columbia Business School) looked at all large publicly available case studies that attempted to identify ROI. There were only 16 major initiatives that were written up from 1987–97. She concludes that:

The vast majority of these studies are unfortunately plagued by a series of a number of methodological flaws, such as inappropriate evaluation design, lack of attention to selection bias, insufficient control for other variables that influence performance, monitoring the impact of training for a relatively short time and using self-reports from the trainees about the productivity gains from training.

(Ann P. Bartle, (2000) ‘Measuring the Employer’s Return on Investment in Training: evidence from the literature’, Industrial Relations, Vol. 39, Issue 3)

Take, for example, an influencing skills programme. Say that the commercial director has identified that he needs his sales people to deliver with more influence. We can diagnose how they are doing at present and ask questions about what success will look like. We can then design and deliver a programme that ensures they are better equipped to influence more buyers more of the time. If we subsequently find out that the reason sales results continue to disappoint is because of a company or product reputation or fault then that would not deliver an adequate ROI and would reflect poorly on us even though ‘we delivered’. We cannot always know what the business needs and leaders must take ultimate responsibility for this. Our job at the pre-workshop stage is to facilitate the right commercial conversations and ideally ascertain as clearly as possible what the core business leaders and sponsors want in terms of changes in behaviour, capability, attitude, knowledge and process. As Donald Kirkpatrick recently wrote:

Contrary to training myth and deep tradition, we do not believe that training events in and of themselves deliver positive, bottom line outcomes. Much has to happen before and after formal training.

If we cannot get an ROI then evaluation can be about ROE (return on expectation). Kirkpatrick suggests it is much more useful to focus on ROE. These are still about business results – the impact that the training programme has made. These expectations, by definition, need to be identified in the pre-workshop stage and are about finding mechanisms that allow us to measure the impact of a programme (between three months and a year after training). The sorts of areas we have seen included as part of calculating ROE include:

- content of the programme;

- efficiency;

- morale of participants and/or team;

- team communication;

- whether a problem has been solved or a gap closed;

- increased customer satisfaction;

- use of technology;

- faster production time;

- fewer errors in following a business process;

- better communication between shop floor and managers;

- improved profitability;

- speedier sales process;

- other quantifiable aspects of organisational performance, for instance numbers of complaints, staff turnover, attrition, failures, wastage, non-compliance, quality ratings, achievement of standards and accreditations.

This level can only be reached if we expand our thinking beyond the impact on the learners who participated and begin to ask what happens to the organisation as a result of the training. It is important to acknowledge that it can be tough to completely isolate training contributions to organisational improvements. Collecting, organising and analysing level 4 information can be difficult, time-consuming and more costly than the other three levels, but the results are often worthwhile when viewed in the full context of its value to the organisation. Some evaluation models have a level 5 which focuses just on financial ROI but we think this is unnecessary.

Of course evaluating at level 4 can go a long way to answering the fundamental question that a CEO might ask: ‘Is it really worth training our people?’ Lots of top HR and L&D leaders nowadays want a place at the top table. They are far less likely to take their place unless they demonstrate and prove that major training initiatives have a real, measurable impact on organisations’ KPIs (key performance indicators).

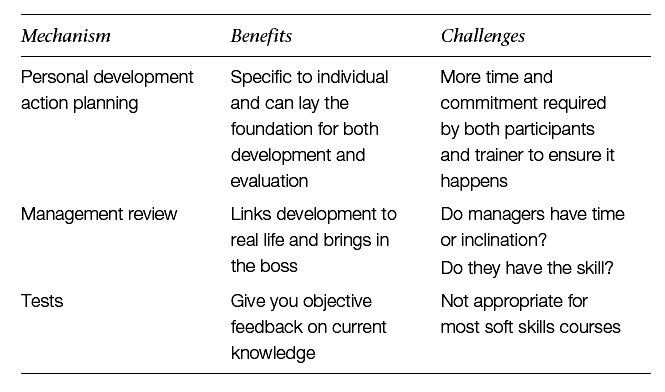

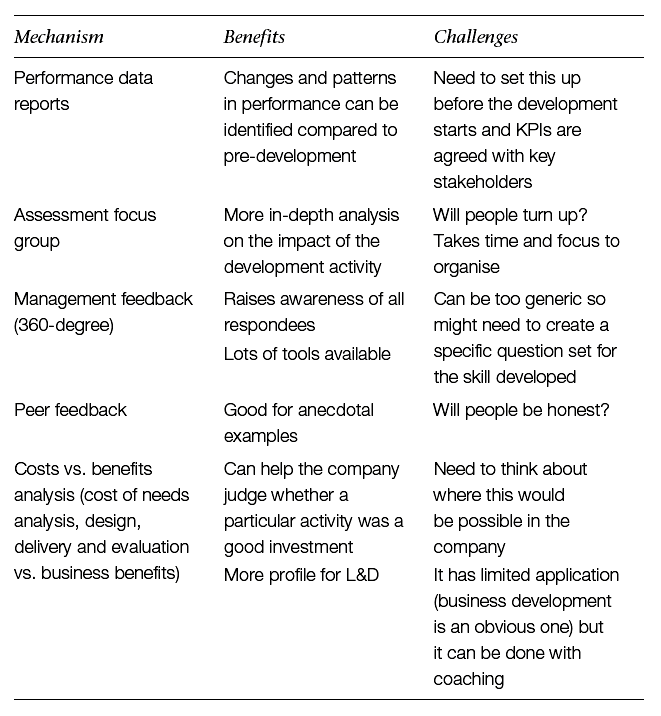

The mechanisms used for evaluation

Here are examples of the mechanisms and tools to use when evaluating the impact of training programmes. We have also included some benefits and challenges in using the various tools:

Level 1 – Reaction

Additional ideas:

- Set aside time to complete on the day – otherwise even level 1 reactions will not all get logged.

- Use names if the organisation encourages openness.

- Change the questions frequently, then participants will consider their responses more carefully. Otherwise many will just think they have seen the same old form lots of times and skip questions.

- Send a summary to all participants as well as all other relevant parties. Often this does not happen.

Level 2 – Learning

Additional ideas:

- If you are going to use tests then apply the same post-course test to employees who did not attend the course but are responsible for similar results (the control group) and then compare the results.

- Use a skills checklist.

- Create simulation exercises for trainees to apply newly learned techniques.

- Highly relevant for certain training such as technical skills.

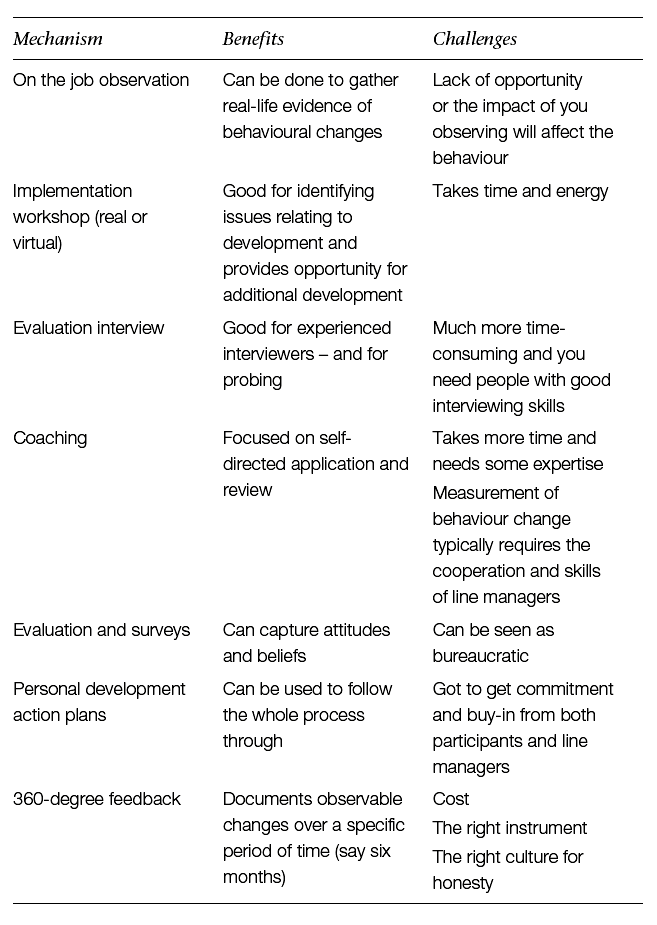

Level 3 – Behaviour

Additional ideas:

- Measurement of behaviour change is less easy to quantify so you need internal support and a rigorous process.

- Simple, quick response systems are unlikely to be adequate.

- Cooperation as well as the skill of observers, often line-managers, are important factors, and difficult to control. Get them trained up or find other ways to monitor behaviour change.

- Can you incentivise staff?

- What tools, resources and equipment are required?

Level 4 – Results

Additional ideas:

- Focus on ROE rather than ROI but look for measures early and get them agreed.

- It is possible that some measures are already in place via normal management systems and reporting. What can you use so you are not reinventing the wheel?

- Agree accountability and relevance with both the management team and the participant group before the start of the training, so they understand what is to be measured.

- Define what internal and external factors will affect your analysis before you start.

The challenge for the training function in an organisation is how to evaluate. Many choose to almost ignore this and hope tough questions are never asked. This is not a useful strategy. We suggest two things: be pragmatic and do something to find out what works. Take action. You may decide, for example, to conduct Level 1 evaluations (Reaction) for all training, Level 2 evaluations (Learning) for ‘hard-skills’ programmes only, Level 3 evaluations (Behaviour) for strategic programmes only and Level 4 evaluations (Results) for programmes costing over a certain financial threshold, say £25,000. It is not enough just to offer great courses, in order to do justice to our people and our roles we need to pay more attention to all six phases of the training cycle and begin to take evaluation seriously.

Summary

Here are the key points we want to leave you with from this chapter:

- Evaluation is about identifying the value of the training to the individual, the job role and the organisation.

- The Kirkpatrick evaluation model is the best model around and organisations would be delighted if training could be evaluated using his four levels: reaction, learning, behaviour and results.

- There are lots of mechanisms to capture information at all four levels.

- ROE is a more quantifiable way of identifying value.