Improvisation and utilisation

How to use what is happening in the room to everyone’s advantage

Process, planning and timing are important elements in business training. Have you ever had to work with someone who is over-zealous about these elements? Jeremy remembers, in the 1990s, starting out in his career as an independent trainer. He was an associate in a London training company and was asked to co-deliver a three-day personal impact training programme for a global organisation in mainland Europe. Jeremy had never before worked with his co-training partner. What stays with him is that she was a zealot. Whenever she took over from him during the day, if he had not covered the subject in exactly the way it had been planned, she would add in the ‘forgotten’ content at the start of her section in an attempt, in her eyes perhaps, to give best value to the participants. However, more abrasively, she cut off questions from the floor in her sections in order to meet the prearranged timings and gave Jeremy ‘feedback’ at the breaks if he had run over time. He is sure, from her perspective, she was being helpful and guiding him as to how to deliver business training, but he found the whole experience nightmarish. She was certainly not the master of the subject in this chapter – improvisation and utilisation.

Not everything can be planned and rehearsed. We have to tap into our natural abilities to improvise. Throughout any ‘normal’ day in business, we spend 95% or more of our time improvising so it is something we can do easily. Utilisation is the idea that anything that happens during a training session can be used. We need to go with the flow and use whatever is happening to our and our audience’s advantage. The skill is often known as ‘thinking on your feet’.

We were working with a financial director of a large organisation last year and whilst he had a great reputation and was clearly very capable, he lost some of his charisma when he was addressing large audiences. He used to ‘hide’ behind a lectern when presenting and not tap into his latent ability to hold the room without using notes. We worked with him so that by the next conference he could do this easily. We can map this over to training. Whilst you will probably be working from a leader’s guide for your sessions you want to avoid rigidly holding these in your hands when you train or obsessively ensuring that you meet a self-imposed timetable that may not be completely geared to meeting the learners’ outcomes.

So this chapter will help you to:

- speak without notes;

- thrive on the unexpected;

- recover when it all goes horribly wrong;

- appear spontaneous;

- use humour appropriately;

Exercise

- Take a step back and ask yourself – what is stopping me being able to improvise and utilise what happens in the training room at will?

- What sort of pay-offs would I have if I was able to do this with ease?

Think about jazz as a metaphor here for the interplay between preparation and delivery. The idea behind jazz improvisation is that the player creates fresh melodies over the repeating cycle of chord changes embedded in a tune. It has been said that the best improvised music sounds to the listener as though it has been composed, and that the best composed music sounds improvised. They may appear opposite but in the best traditions of jazz, they merge in a unique mixture. As Duke Ellington once said:

You’ve got to find some way of saying it, without saying it.

In business training, the level of actual improvisation will vary, depending on the subject matter and the group, and will be on a continuum between tight (keep to structure unless something unusual happens) and loose (fluid content adjusted in real-time to the group needs).

On a very practical note you need to improvise when these sorts of things happen during training:

- You have a demotivated group.

- The technology stops working.

- Someone asks a tough question.

- Someone challenges your or the group’s thinking.

- Something unexpected occurs.

Four steps to improvising well

How do you have the confidence to hold the room and work with your own knowledge and expertise, without constantly referring to your written plan? Some people appear to do this effortlessly – what is the secret? Here is a four-step process, which applies to all improvising and speaking without notes.

Step 1: create and maintain strong beliefs about yourself

Most trainers we know do not have the amazing and remarkable skills of improvisation of the players at London’s Comedy Store. That group has taken 27 years to hone many skills to ensure their improvisation provides a laugh. However we were struck with a comment in 2010 by one of the original troupe, Richard Vranch, when they were celebrating 25 years in the business, which must have come from a strong positive belief about their methods:

We’ve got this down to a level where there’s no make-up, costumes, preparation, directors, rehearsal, line-learning, nothing. We just turn up and do it.

Your beliefs (or mind-set) underpin a lot of your actions when you are attempting to influence a group, either consciously or unconsciously, in a training environment. A belief is a mental acceptance of something as being true or real. It is not necessarily the truth. Our beliefs often change throughout the course of our lives. Beliefs are not the truth; they are just true for us as individuals while we choose to hold them. Some beliefs stay the same, some beliefs change. It is surprising how quickly beliefs can change. Of course we are conditioned by all sorts of elements around us – parents, education, friendships or the working environment. And yet ultimately we can let self-limiting beliefs disappear into the museum of old beliefs, to be replaced by more positive beliefs.

Quite simply, if you believe that something is possible for you then you are likely to attempt it and achieve the result that you want. If you do not feel it is possible then you may simply avoid taking any action, convinced that it would not result in achieving your desired outcome.

Sometimes we hold on to beliefs about ourselves that are just not helpful. So what beliefs are holding you back? What is your mind-set when you train? What could you believe about yourself that would allow you to have more freedom when you are training? For example if you really think that ‘I cannot present with fluency’, ‘I am not as good as other trainers’ or ‘I must stick to the script’ you will need to prove to yourself regularly that these beliefs are true.

A great belief to have, for example, is: ‘I can work with anything that happens in the training room’ or ‘I know enough about this subject to go with the flow’. These beliefs would filter into your behaviour and help reinforce your latent capabilities.

Step 2: work on your knowledge, practise and learn

If you can become an expert on what you are delivering – perfect. If not, make sure you become as knowledgeable as you can. Then learn the key messages that are incorporated into the design. Finally, a useful tip is to learn by heart how you are going to introduce the key sections, especially the beginning. If you are able to learn the first 1–5 minutes of your opening session this will do two things: give you a lot of confidence and highlight to the audience that you have a high level of credibility. You can get this in the muscle by rehearsing – ideally in the environment in which the training will take place. A good adage here is that ‘rehearsal is the work, performance is the pleasure’.

Step 3: get into a resourceful state and trust in your unconscious

Choose a routine that allows you to be in a resourceful state even before the participants enter the room. If you have not already read it, read the section on confidence included within the C3 Model of Influencing (see Chapter 14), and identify through experience what will work for you.

If you know the audience, understand the subject well and have strong content, you are ready to begin. Your unconscious mind will know what to do as long as your conscious mind does not get in the way. Think about playing a musical instrument or a particular sport. If you have done the practice, you can play well and yet we can trip ourselves up with our own self-doubt. Banish doubt by knowing that you are fully prepared and can deliver.

Step 4: go with the flow in the room and focus on the learning outcomes

There is a paradox at the heart of outstanding business training. Most trainers, business sponsors and indeed the group itself like to have a plan. And yet often the best learning and the most important shifts in thinking come from spontaneity. The way through this is to focus on the learning outcomes that have been decided as part of the design and that are complemented by what the learners themselves want on the day. The trick is to have these in the front of your mind – where do we need to get to by the end of the session? This then lets you go off piste as long as it is in service of the learning outcomes. In fact this approach frees you up to be spontaneous. Sometimes, as a trainer, you need to recognise and then have the confidence to veer from the script and work with a challenge from the room that is fundamental to getting the right result. We need to be constantly readjusting the tiller to help steer us to the destination. Once the start is in the bag, the more you are open to what is happening in the room and the more you practise improvisation in the moment, the better you will get.

Utilisation

If you like comedy, one of the skills of stand-up comedians when you see them live is how they cope with hecklers and comments from the audience. The term ‘heckler’ originates from the textile trade, where to heckle meant to tease or comb out flax or hemp fibres. Staff who combed out flax were renowned as the most radical workers. Whist the hecklers toiled in the factory, a worker would read out the day’s news and others would butt in with constant interruptions.

What most really good stand-ups do is utilise the comments from the hecklers, not ignore them. This is an example of the concept of utilisation. This is about utilising whatever happens in the room rather than ignoring it. So rather than hoping someone who heckles will just go away and be quiet, comedians will use these types of comeback:

Jack Dee Well, it’s a night out for him ... and a night off for his family.

John Cooper Clarke Your bus leaves in 10 minutes ... Be under it.

Arthur Smith Look, it’s all right to donate your brain to science but shouldn’t you have waited till you died?

Heckler I met you at medical school.

Frank Skinner Ah yes ... you were the one in the jar.

Taken from Stand Up Put Downs, by Rufus Hound (Bantam Press)

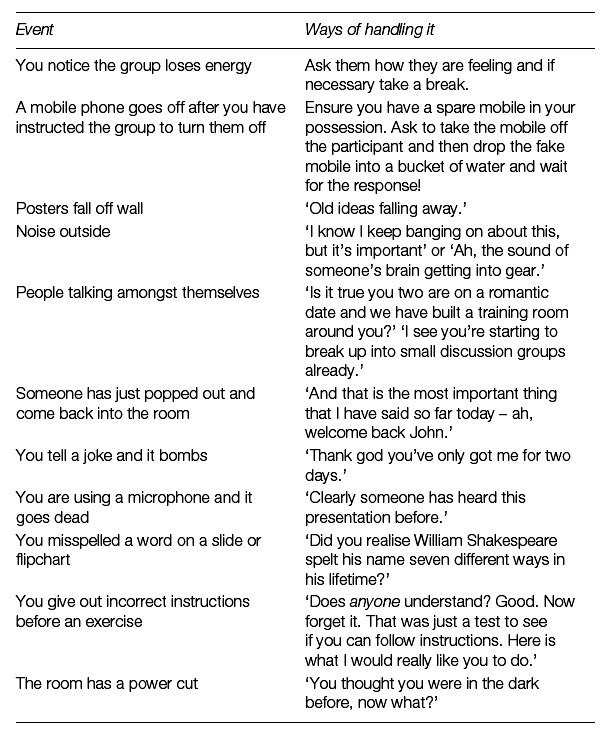

So, in business training, the idea is that you use whatever is happening in the room. Some trainers choose to ignore what is happening and this can create a disconnect between the trainer and the group. It is about being real, spontaneous and sometimes taking risks. You use it too for humorous purposes, to demonstrate a point, build a strong connection with the audience and raise awareness. Here are some examples:

Example

The importance of humour and fun in business training

When we ask trainers on courses about the qualities that make up an effective trainer or an outstanding presenter, humour almost always comes up. Humour has the ability to both divide and unite people. Used well it is a vital tool in the trainer’s armoury. It shines a light on the absurdity of so much human behaviour and allows us and the participants not to take things too seriously. It is also, thankfully, timeless, and occurs in all cultures.

It appears to be an objective fact that we are laughing less nowadays. Children tend to laugh about 400 times a day. Over 70% of adults smile less than 20 times a day at work. The International Society for Humor (the very existence of this august institution is enough to make you smile) found that laughter is down 66–82% worldwide from what it was in the 1950s. In the 1950s people laughed on average 18 times per day. Today, we are lucky if we average between 4–6 times per day. It is all getting very serious.

The power of humour in a training environment and its positive impact – laughter and fun – should not be underestimated.

LAUGHTER IS THE BEST MEDICINE

A recent study found that people laugh six more times in the presence of one person and 30 more times in a group of people. Laughter benefits many of the body’s vital systems: the respiratory, cardio-vascular, hormonal and even immune system. Even smiling releases beneficial endorphins and hormones. The immediate benefits of laughing out loud are not exclusively centred on the release of ‘happy chemicals’ (endorphins) from the brain which help store learning. The knock-on effect on the body’s internal organs and the increased intake of oxygen and expulsion of carbon dioxide is provoked by really hearty laughter. Additional research has demonstrated that throat mucus antibodies increased after a 20-minute laughter session and that natural killer cells (those that fight cancer, for example) become more potent after laughing.

So here is the case for using humour in training. Humour that works well and creates laughter and positive energy in the room:

- demonstrates that the trainer is relaxed and resourceful;

- relaxes individuals and may relieve any nerves some may be feeling;

- establishes a bond with the group;

- maintains interest in the subject and the participants’ attention;

- can help emphasise a specific point;

- can turn an awkward moment into an enjoyable experience;

- is an effective tool to increase learning, creativity and retention.

Humour done well can be a valuable shared experience that everyone in the room can relate to, has possibly been through, or can picture happening to them. Very few training sessions are so serious that humour is misplaced. Indeed, Dr Jason Goodson (Utah University) reports that exposure to a dose of stand-up comedy had a positive effect on depressed patients. Dr Stanley Tan who works at the Loma Linda Medical Center in California, who has studied the neurochemistry of laughter, says: ‘Laughter brings a balance to all the components of the immune system.’

Of course we cannot all be stand-up comedians. Some trainers will no doubt have strong beliefs about their capacity for humour. Some are more serious or less naturally inclined to use humour. Indeed there is something in the very nature of humour which is tough to pin down. No analysis will get us to the point where we can understand and therefore guarantee that if you do this or say that you will get a smile, a titter or uproarious laughter. But for pragmatists and activists (see Chapter 8 for Honey and Mumford’s learning styles) the key question will still be: how do you do this convincingly and with authenticity?

It is certainly not about being a laugh a minute gag person. Some people can do that really well but there are of course risks to these ‘set piece’ jokes. They may possibly offend, be culturally unfathomable or misplaced. So we are not proposing a workshop to attend on joke telling. Here are 10 ways in which humour has worked for us and other trainers:

- It is mainly about the style of delivery. You may be delivering something that is serious, important or game changing or you may be training on new products or processes. Whatever your line of work, demonstrate a lightness of touch when you are on your feet. If you are over-serious, you run the risk of people becoming tense or even more nervous than they might already be feeling.

- Be open to the possibility of humour when it arises. When using humour it should flow naturally from the content or from the training situation.

- When observing one outstanding trainer recently, Ed Lamont, we counted 24 examples of humour before the lunch break. Only about 15% were planned, the rest arose from the interaction with his audience. If something pops up as a response to a question that you think will work, give it a go and monitor the response.

- Use self-deprecating humour (humour aimed at yourself). For example when you say a sentence that comes out jumbled you might say ‘easy enough for me to say’ or ‘later on I’ll pass out a printed translation of that sentence’. If you lose your place and have a temporary mental fugue, use the comedian Steve Martin’s favourite line for this situation, ‘Where was I? Oh yes! I was here!’ (Take a step to the side.)

- Find out what works. A simple way to do this is to try a story or a one-liner and see what response you get. This is what stand-up comedians do before a tour. They test their material and then retain the best bits. The more you then tell a story or use a joke/one liner, the surer you are of getting a positive response. If you are looking for stories/one liners that we have accumulated over the years go to www.ftguidetobusiness.com

- Always start your training with the credible voice pattern (see Chapter 14 section on the C3 Model of Influencing). However within the first few minutes you can add a dash of humour which will help set the tone, using the connection voice pattern. For example, we have often used this as part of our introduction when we deliver work for a key client:

‘Over the last few years X (a great British luxury firm) has been a runaway success story. We have never worked with a company that has so much passion for its business. In fact we have been so impressed that we have both bought shares in X. So you think this conference is all about you – in fact we are protecting our investment!’

We got a titter or smile of recognition every time and it also emphasises our commitment to the brand.

- Use humour to suggest to people that they can change easily (often the purpose of business training). Bernie Siegal (doctor, writer, trainer) says: ‘Humour’s most important psychological function is to jolt us out of our habitual frame of mind and promote new perspectives. People continue to see humour if they retain a childlike spirit – a sense of innocence and play.’

- Take a story (ideally one that has happened to you) and embellish it (add in some new facts, over-sell, add dramatic pauses) until it becomes even more amusing and helps emphasise a key point you are making. Then the more you tell it, the better impact it will have.

- Use humour to defuse unexpected situations.

- Use funny props – smiley face, rubber chickens, small toys, as long as they fit the theme and audience. For example we sometimes use a toy monkey when we talk about how to banish nerves and access a resourceful state when we teach presentation skills. We ask: ‘Do you want to get the monkey off your back once and for all?’

A WORD OF CAUTION

Don’t let humour harm your key training messages. If participants experience too much humour in a training programme they can walk away thinking the whole thing was a joke. Provide enough humour to reinforce the relevance of the training and to help learners recall your messages but be careful not to turn the classroom into an open stand at The Comedy Store!

A final note on humour: positive emotions accelerate learning, negative emotions inhibit learning so tap into your humorous vein in the training room and let the blood run hot.

Summary

Here are the final points we want to leave you with from this chapter:

- Not everything can be planned and rehearsed. You need a balance between planning and working in the moment with the group – we have to improvise and utilise.

- Playing jazz is a useful metaphor here because you have to practise to get really good and yet the best jazz musicians improvise within a melody.

- There are four steps to being able to improvise easily in training:

- Step 1: create and maintain strong beliefs about yourself;

- Step 2: work on your knowledge, practise and learn;

- Step 3: get into a resourceful state and trust in your unconscious;

- Step 4: go with the flow in the room and focus on the learning outcomes.

- Utilisation is about using whatever is happening in the room for a variety of purposes which serve the interests of the audience.

- Humour lightens the mood and allows everyone to relax and have fun. It is a vital tool for the trainer.

- Humour done well can be a shared experience.

- It is not about being a stand-up comedian.

- We have provided 10 good ideas about using humour in training.