6 The democratisation of industrial relations in the Czech Republic — work organisation and employee representation

Case studies from the electronics industry1

Introduction

The organisation of work is influenced by the growing demands of the market (for quality and service, short delivery deadlines or flexibility), by technological development (automation and innovation), by changes in the composition of the workforce (including changes in lifestyle and domestic routines as well as increased educational levels) and by the democratisation of social relations. In reaction to such society-wide trends advocates of different theoretical approaches to enterprise management have suggested and implemented a range of innovations in the organisation of work over the past few decades. Typically this has involved providing scope for greater autonomy in the accomplishment of work tasks, integrating partial work tasks so that jobs are less monotonous and make use of the knowledge, abilities and qualifications of workers, and rotating workers between different posts. Work is often carried out in small teams, enabling individuals to assume greater authority as well as to gain experience of different types of work. This form of organisational structure is designed to simplify communication and facilitate better coordination of the work process. The expansion and overlapping of job descriptions is essential to effective team work, where workers must be able to stand in for one another. Such innovations place new demands on workers in terms of qualifications, authority relations, relationships with co-workers, responsibilities and working hours. Thus there is a need to ensure the training of workers to enable them to carry out a wider range of tasks. The classical hierarchical relationship between supervisors and supervised becomes a partnership based on the coordination of the work of subordinates, in which the role of team leader may be interchangeable according to who has the most experience of a particular aspect of the work process.

In the Czech Republic, just as in other advanced economies, the introduction of such new forms of work organisation in recent years has aimed to raise productivity, streamline organisational structure and at the same time enable employees to gain greater satisfaction from work and more easily identify with the firm's product. But along with these advantages, new work practices also carry disadvantages. Among those mentioned most often is the risk of placing too much faith in the initiative and responsibility of workers and in their ability to learn, which may reduce the applicability of work rotation. Such forms of organisation will bring rewards only as long as workers feel the need for personal and professional growth. They clearly also have most to offer at those points in the pro-duction process where a high degree of flexibility in terms of work tasks is necessary, and where work demands regular two-way communication or cooperation between personnel from different sections. Some experts in enterprise management point to a regression in work practices in certain branches or firms. In particular, several vehicle factories have reintroduced forms of work based predominantly on conveyor belt systems which dictate work tempo for the entire production process.

Besides organisational changes gradual trends are also discernible in the field of employee representation at the enterprise level in the Czech Republic. A drop in the number of employees organised in trade unions has been accompanied by legislative changes introducing two separate institutions for communication between employers and employees, after an amendment to the Labour Code enabled the formation of employees' councils and the appointment of health and safety at work representatives. However these institutions are only permitted where there is no trade union organisation. If none of these is present the employer is obliged by law to negotiate directly with employees.

The level of union organisation in firms is itself influenced by changes in work organisation. Union spokespeople cite the introduction of team work — with its relative autonomy within the framework of the organisation of the firm — as one cause of their loss of influence: teams allegedly refuse to deal with unions on certain matters, above all on wage issues, working hours and safety at work. Teams ‘feel that they can defend their interests better and with greater effect, without realising that in factories which operate like this an employer can enforce his/her intentions far better, often to the detriment of the workforce’ (Kosina et al. 1998: 24).

In the following section we attempt to show, using two industrial enterprises as examples, how the content of work has changed for manual professions,2 and to identify those factors which influence the attitudes of workers in these firms towards their trade union organisation. In the case of Firm A it was possible to track these changes through time, since the same questions were put to employees in 1995 and 2000. Our analysis of employee attitudes therefore relies more heavily on Firm A, given that Firm B was not covered by the first phase of research in 1995.

The two firms operate in the electronics industry. Both had originally been state enterprises, and underwent privatisation in the early 1990s, overcoming economic difficulties caused mainly by the loss of traditional markets. In both firms a trade union organisation (affiliated to the metalworkers' union OS KOVO) has existed continuously and the level of organisation of the workforce exceeds the average for OS KOVO local organisations. Workers in both firms are covered by a collective agreement of a high standard. Firm A became a state share company in 1991 and was privatised in 1993 by means of coupon privatisation. Since then a whole series of rationalising measures have been introduced: several production facilities were gradually shut down, the organisational structure of the firm was simplified, and costs were cut across the board in response to the collapse of markets. At the same time there was a restructuring of the product range and the cycle of product innovation was accelerated. A result of these changes was a reduction in the workforce by 28 per cent in 1999 (to around two-thirds of its 1995 level). One of the firm's strong points is that it has managed to retain an independent research and development capacity in spite of rationalisation. Fifty-eight per cent of production now goes for export, mostly to EU countries, and exports made up 55 per cent of an overall turnover in 1999 of Kčs 2,400 million. Nevertheless, planned profits have not been achieved. Firm B was privatised in 1992 as a share company. Since 1995 the workforce has only been cut to around four-fifths of its original size, although staff turnover has been high. The firm has not carried out such fundamental organisational changes as Firm A and has had greater difficulty defining a long-term development plan.

Changes in the organisation of work from the perspective of employees in manual professions

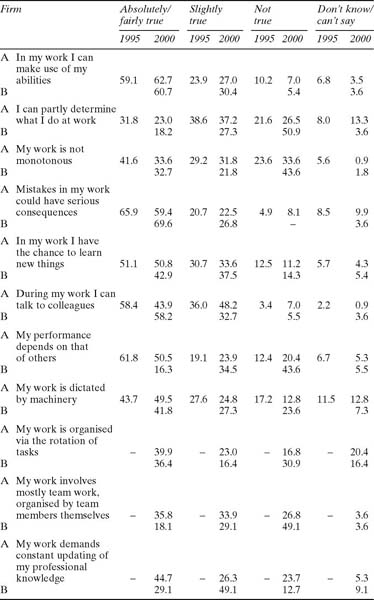

New forms of work organisation affect most of the manual workforce in Firm A, in which 36 per cent of manual employees in 2000 stated that they regularly work in teams and a further 34 per cent confirmed that their jobs sometimes involve team work. The comparable figures for Firm B were 18 per cent and 29 per cent, which accords with the higher share of respondents who said that their performance does not depend on the performance of co-workers (43.6 per cent as against only 20.4 per cent in Firm A), and the higher share who said their work is not organised by the rotation of tasks (30.9 per cent compared with 16.8 per cent in Firm A).

However a comparison of various features of team work (decision-making about work content, dependence on the performance of others) in Firm A in 1995 and 2000 suggests a partial regression to more traditional forms of work organisation. For instance, in 2000 only 23 per cent of manual respondents claimed they could, even to a certain extent, control what they do at work, against 31.8 per cent in 1995. The number of those stating the interdependence of their own performance and that of others also fell in this period, from 61.8 per cent to 50.5 per cent. Likewise in the sphere of communication, another important indicator of collectively organised work, a drop was recorded in the proportion of respondents who feel they can talk to their colleagues during the working day. This could reflect a rationalisation and intensification of the work process. The one contradictory indicator was a rise in the number of workers who feel their work is not monotonous (from 23.6 per cent in 1995 to 33.6 per cent in 2000). To be able to draw convincing conclusions about the real tendency in relation to the introduction of new forms of work organisation in Firm A we lack fully comparable data from 1995, when the question, ‘Does your job involve team work?’, was unfortunately not included in the survey. Table 6.2 gives a more detailed breakdown of workers' responses.

Table 6.1 shows how work content for manual professions in Firm A changed between 1995 (when organisational changes were beginning) and 2000 (when they were in full flow) and also offers a comparison between Firms A and B. Some penetration of computers into production is evident in both firms, with around 4 per cent of manual workers declaring that their jobs involve work with computers. In Firm A we know that this is one of a number of completely new activities which were demanded of manual workers in 2000, others being administration and data processing; there has also been a substantial increase in the amount of time spent servicing and maintaining machinery. Greater responsibility has evidently also been shifted on to manual workers in areas such as quality control and supervision of certain parts of the production process. Conversely responsibility for technical development has been consolidated in the hands of qualified specialists.

In Firm B, where reconstruction has not been so thoroughgoing, the data shows that the nature of work in manual professions is not as complex as in Firm A. The testimony of manual employees in B confirms that substantially fewer responsibilities for the final product, including its administrative assurance, have been delegated to them (for example, ‘quality control and surveillance’ is recognised as part of their job by 41 per cent of workers in A but only 27 per cent of workers in B). Despite the fall in manual workers' independence recorded in Firm A between 1995 and 2000, the greater complexity of their work content in comparison with Firm B is also confirmed by responses on autonomy and the extent of competences delegated to workers. Of manual workers in Firm B 51 per cent felt they could not determine their own work to any extent, whereas in Firm A the figure, even in 2000, was only 27 per cent.

The changes in the character of work and in the evaluations of their work by employees summarised above indicate a gradual modernisation of production and work organisation involving greater utilisation of the synergetic effects of team work. As has been noted, however, this process is accompanied by a number of contradictory trends, such as the partial narrowing of scope for workers to determine their own work, the greater

Table 6.1 Changes in work content in manual professions (figures show the percentage of respondents who perform each activity during their normal work, i.e. the remainder do not perform that task at all)

| Firm A | Firm B | ||

| 1995 | 2000 | 2000 | |

| All manual | All manual | All manual | |

| workers | workers | workers | |

| (n=91) | (n=120) | (n=56) | |

| Work at machines or conveyor belts |

57.1 |

75.0 |

69.8 |

| Maintenance | 5.5 | 30.2 | 34.8 |

| Quality control and inspection | 6.6 | 41.1 | 26.5 |

| Sales, marketing, service | 2.2 | 3.8 | – |

| Programming, specialist computer work |

0.0 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

| Administration, data processing | 0.0 | 6.3 | – |

| Managerial work | 2.2 | 1.3 | – |

| Technical development, research, specialist activity linked to product innovation |

7.7 |

2.6 |

4.1 |

| Development of technology and production systems, other engineering tasks connected with the production process |

2.2 |

2.6 |

– |

| Other tasks | 33.0 | 33.3 | 40.4 |

individualisation of production entailing a lesser degree of interdependence between workers' performances, and probably also the loss of opportunities to communicate with colleagues. Even though manual workers have been entrusted with more demanding tasks we did not detect any significant increase in the number of those who felt they could make use of their abilities (59.1 per cent of workers in Firm A in 1995 and 62.7 per cent in 2000; 60.7 per cent in Firm B in 2000). A slight decrease was recorded in the number of those who said that work offers them opportunities to learn new things (in Firm A the figure was 51.1 per cent in 1995 and 50.8 per cent in 2000, in Firm B 42.9 per cent in 2000). Given the greater complexity of manual job descriptions in Firm A it is logical that there were more workers who evaluated their jobs as demanding enough to require consistent improvement of their professional knowledge (44.7 per cent, compared with 29.1 per cent in B). But in spite of this a mere 8.6 per cent of manual workers in Firm A said they had undertaken a training course organised by the enterprise during the past five years, whilst 16.1 per cent of Firm B's workers had done so. This apparently testifies to a lack of effort on the part of the firm management to make effective use of available human resources.

Table 6.2 Self-evaluation of work undertaken in manual professions (per cent)

What impact did new forms of work organisation have on the relationship of blue-collar workers to managers, co-workers and trade unions? The subdivision of employees into small work groups with substantial autonomy leads to the strengthening of relations within the group, to better relations with management, but at the same time to looser ties with unions. Employees tend to take care of their needs and demands through immediate superiors and correspondingly drift away from the union organisation. Table 6.3 shows how over the years manual workers in Firm A have adjusted their evaluations of their own relationships with superiors and co-workers. For those who say they work in teams3 the growth in satisfaction with both these relationships was especially pronounced. Comparing the two firms, the greatest differences were observed in assessments of the level of trust between managerial and ordinary workers and between workers and their immediate superiors. In Firm A the satisfaction of workers with this latter relationship is probably the cause of the weakening position of unions which union functionaries admitted to. Conversely in Firm B the low degree of trust which prevails between workers and their immediate superiors apparently contributes to the growth of union influence.

Here it should be stressed that employees generally have a positive relationship to their firm. More than two-fifths (43 per cent) of employees, including a quarter of manual workers, would be willing to do everything in their power for the success of Firm A, and in Firm B the proportions were higher still (48 per cent of all workers and 32 per cent of manual workers). The most common attitude presupposes a reciprocal relationship between employee and firm: 53 per cent of all workers (69 per cent of manual workers) are prepared ‘to do as much for Firm A as the firm does for me’,

Table 6.3 Manual workers' evaluations of relationships to superiors and coworkers (per cent)

with 48 per cent of Firm B's employees (62.5 per cent of manual workers) adopting the same stance. Only 1.5 per cent of respondents (2.6 per cent of manual workers) in Firm A and 1.0 per cent of employees (1.8 per cent of manual workers) in Firm B claimed indifference to their firms' business. In this respect it appears that Czech employees have an even closer affinity with their firm than Slovak employees (cf. Cambáliková in this volume).

Satisfaction with conditions at work

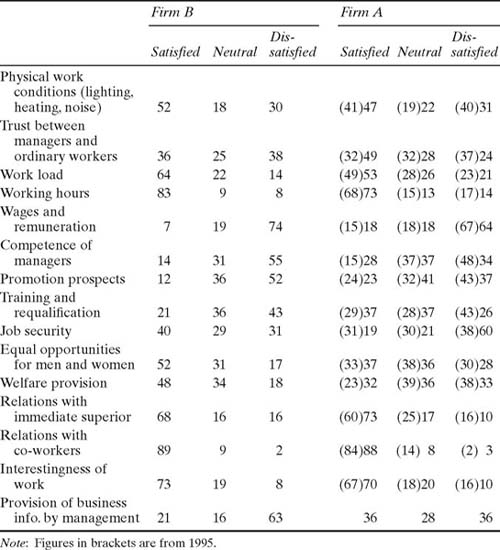

An integral element of workers' attitudes to their firm is their satisfaction with conditions at work, which we tracked using fifteen variables (an overview is given in Table 6.4). Dissatisfaction prevailed with five out of fifteen aspects of work conditions in Firm A and with six in Firm B. In both cases the highest level of dissatisfaction concerned wages, along with job insecurity in Firm A. On the other hand the factors which contributed most positively to the atmosphere in both work collectives were good relations with co-workers, interesting work, good relations with immediate superiors and working hours.

The aspects of work with which employees of Firm A were more satisfied than those of Firm B were: wages (in Firm A 18 per cent and in Firm B 7 per cent were satisfied), the competence of management (A 28 per cent, B 14 per cent), trust between managerial and ordinary workers (A 49 per cent, B 36 per cent), training and requalification (A 37 per cent, B 21 per cent), provision of business information by management (A 36 per cent, B 21 per cent) and promotion prospects (A 23 per cent, B 12 per cent). A greater share of satisfied workers was recorded in Firm B in connection with job security (B 40 per cent, A 19 per cent), welfare provision (B 48 per cent, A 32 per cent), work load (B 64 per cent, A 53 per cent), working hours (B 83 per cent, A 73 per cent) and equal opportunities between the sexes (B 52 per cent, A 37 per cent).

Employees of Firm A, as noted, feel a loss of security about their employment, something which is confirmed by comparing the survey data for 1995 and 2000. A heightened sense of existential threat and resulting feelings of dissatisfaction are connected with the comprehensive restructuring of the enterprise which has occurred in recent years, and which involved the closure of one plant, resulting in the redundancy of around a thousand employees. Firm A's employees are also less satisfied with welfare provision, although the situation here has, in their view, improved since 1995. Social policy in the enterprise is gradually being shaped into a means of promoting long-term motivation among personnel and moving away from short-term instrumental benefits aimed at satisfying individual social needs. Significantly, the increase in employee satisfaction with their employer's social policy occurred in spite of cut-backs in spending on some traditional areas of enterprise social provision such as employee recreation and subsidised meals (although the enterprise catering system has been thoroughly overhauled).

Table 6.4 Satisfaction with individual aspects of conditions at work (per cent)

Overall 67 per cent of employees in Firm A were satisfied with their job in 2000 (15 per cent were dissatisfied), with slightly fewer expressing satisfaction in Firm B (61 per cent), although fewer were actually prepared to indicate dissatisfaction (13 per cent). A clear improvement is detectable in Firm A since 1995, when 48 per cent of respondents expressed satisfaction and 24 per cent dissatisfaction.

Social mobility and authority relations in the firm

From the perspective of management (or governance) Firm A has a more open organisational structure than Firm B. 31 per cent of employees in the former felt that managers provide professional and career development opportunities for the workforce, but only 16 per cent thought so in the latter. Comparison of the starting and current posts filled by employees largely supports this evaluation: in Firm B career progression was noted more often among manual workers (19 per cent had been promoted since joining the firm, whereas only 13 per cent had in A); however among administrative workers (A 18 per cent, B 6 per cent) and among technical staff (A 34 per cent, B 28 per cent) promotion was a more common phenomenon in A. Indeed demotion was more often found among B's administrative and technical staff (13 per cent of administrative workers and 22 per cent of technical workers occupied posts below their starting positions in B, but only 5 per cent and 10 per cent respectively in A).

The determining factors influencing career mobility chances in the opinion of employees were: (in Firm A) work performance, productivity or results (61 per cent said this was important in gaining promotion) and to a lesser extent good relations with bosses (23 per cent); (in Firm B) performance and results (35 per cent), good relations with bosses (28 per cent) and assertiveness (12 per cent). Thus employees of Firm B portray an environment in which mobility chances are dependent on a combination of factors, whereas Firm A is perceived by its employees as an organisation which essentially rewards on the job performance and results.

Relations between managers and ordinary workers in Firm B are apparently highly rigid. The clear majority of employees (68 per cent) believed that managers evade responsibility (51 per cent thought the same in A), 53 per cent said they fail to delegate competences to the employees they manage (38 per cent in A), whilst only a minority felt managers show an interest in the opinions and ideas of their staff (55 per cent in A). Not surprisingly, as Table 6.4 shows, trust within the hierarchy of the firm is scarcer in B than in A and satisfaction with the competence of managers is lower. Only a quarter of employees in B expressed conviction that the management has a conception of the firm's long-term development, compared with 54 per cent of employees in A. At any rate strategic ideas are more rarely divulged to employees (82 per cent in Firm B felt uninformed about company strategy, and only 47 per cent in Firm A). However employees do not project their criticisms on to immediate superiors in either firm: 68 per cent of employees in B and 73 per cent in A were satisfied with the most direct form of authority relations they are involved in.

Perceptions of foreign ownership

Given that the penetration of foreign capital into the Czech Republic, either by investment in an existing enterprise or by opening completely new plants, is an ever more common occurrence, some of the most interesting survey findings related to employees' perceptions of and expectations from foreign investment. In each firm this was a relevant issue: Firm B already had direct experience, as 25 per cent of shares belonged to a foreign owner in 2000, while Firm A was looking for a foreign strategic partner. Expectations of tightened work discipline are clearly associated with foreign ownership (such expectations are 20 per cent higher in Firm B), as are, to a lesser extent, hopes for improved managerial competence. Actual experience with foreign ownership also seems to produce expectations of greater stability of employment and higher wages in Firm B. Yet where direct experience is lacking, in Firm A, the mere prospect of foreign ownership is viewed as a potential cause of disruption to employment and wage-cutting. In both situations negative expectations are associated with foreign ownership concerning cooperation between management and trade unions and the representation of employee interests. In sum, foreign ownership is viewed in terms of a trade-off between positive and negative expectations.

Trade unions in changing circumstances: employees' perception of their role

The level of unionisation of both firms' workforces has followed the norm in the Czech Republic of a continuous fall since 1989. The most significant cause of falling membership was the extensive privatisation of industry in the course of the 1990s. Owners of newly emerging firms or operational units mostly sought to prevent the establishment of union organisations in their workplaces and employees were afraid to join existing workplace union organisations, fearing possible sanctions by the employer. Available data and national union leaders' own estimates indicate a level of unionisation of around 33 per cent of the Czech workforce in 2001.

Aside from the fall in membership unions have also had to cope with new roles associated with political democracy and a market economy. Until the amendment to the Labour Code which came into effect at the start of 2001 unions were the only organisations empowered to represent employees and negotiate with employers in order to sign enterprise collective agreements. The new legislative environment presupposes greater plurality in the representation of employees, abolishing the monopolistic position of unions, if only on paper for the time being. However unions retain a privileged status: wherever they exist they are automatically considered to be the sole representative of the employees and the partner of the employer for the purposes of collective bargaining; other forms of representation only come into play in unions' absence.

The decline in union membership is also related to the reproduction of social norms of behaviour and social attitudes which are the heritage of the former regime and support a largely formal or passive mode of belonging to unions. A section of the labour force has yet to fully understand that the main role of unions lies in securing through bargaining employees' existential needs, wages and work conditions. Nevertheless a comparison of data from 1990 and 1998 reveals that attitudes towards unions were changing during the 1990s, and that the general level of trust unions enjoy among employees has risen.

In the second half of the 1990s there was a reduction in collective bargaining in Czech enterprises, as measured by the number of successfully negotiated collective agreements and by the number of employees covered by such agreements. Only in the past two years has this reduction been compensated for by more widespread extension of higher-level collective agreements practised by the Social Democrat government which took office in 1998, ‘partly as a mechanism to encourage enterprises to join business associations' (Rychlý 2000: 3). The total number of employees covered by collective agreements was estimated at 40 per cent of the workforce in 2000 (ibid.).

In both firms surveyed here union organisation was above the national average for firms in which the KOVO union operated in 2000. One of the explanations is that the firms themselves and their union organisations have enjoyed an uninterrupted existence. In Firm A 59.7 per cent of employees were members of the union organisation, in Firm B 76 per cent. Employees of both firms, with just a few exceptions, were aware of the existence of the enterprise collective agreement and expressed satisfaction with its content. Their subjective evaluation is in fact corroborated by a comparison of both firms' collective agreements with the norms for the sector.

Inevitably there are differences between the interests of employees and managers, manual workers and administrative staff, which are given by their different positions within the enterprise and the distinct aims they each pursue. However they ought to have a common interest in the production and productivity of the firm, since these fundamentals influence profit and wage levels, safety at work, and so on, and this should underpin a certain degree of intra-enterprise solidarity. In reality, according to collated data for both enterprises, the interests of employees accord most closely with those of their immediate superiors (28.6 per cent declared identical interests and 38.6 per cent similar interests) and with those of manual workers at the plants (19.5 per cent identical, 41.6 per cent similar). In both these respects the level of solidarity was higher in Firm A than in B. In Firm A employees expressed greater solidarity with these two collective actors than with the union organisation, a pattern which was reversed in Firm B, probably because of a greater representation of union members in the sample. Significantly, however, both work collectives exhibit a tendency towards the kind of ‘dual identity’ identified by Čambáliková for the Slovak firms in the same study (see her chapter in this volume). In both firms the lowest degree of solidarity was declared towards the top management (30.5 per cent declared partially divergent, 27.3 per cent largely divergent and 10.9 per cent contradictory interests) and towards the enterprise director. Compared with the situation in 1995, antagonistic opinions were generally less frequent in Firm A in 2000, the one exception being a distancing of employee interests from those of technicians and engineers.

Both the survey data and in-depth interviews conducted in the two firms support the following conclusion: the greater the difference between the interests of workers and their immediate superiors, or between workers and management (which is probably given by inadequate communication), the greater a compensatory identification of workers' interests with their union organisation. Middle management, especially lower middle management (foremen and workshop managers), traditionally act as intermediaries between ordinary workers and managers in these firms. But where those channels work badly, alternative, albeit often less effective solutions are sought for the realisation of interests through collective actors.

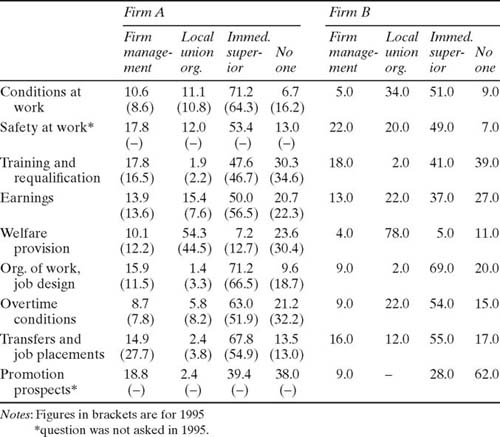

Positive evaluations of immediate superiors also came through strongly in responses to the question, ‘Who best represents the interests of employees?’, as Table 6.5 shows. Whether in respect of work conditions, safety at work or the organisation of work it was immediate superiors who best represented the interests of the greatest number of respondents. The

Table 6.5 Collective actors which best represent employee interests in specific areas (per cent)

domain of unions, according to the same section of the questionnaire, is welfare provision. The spheres in which employees felt the greatest deficit of interest representation (where they most often responded, ‘no one represents my interests’) were training and requalification and promotion prospects.

Despite high levels of union organisation in both firms, in neither case are employees especially active participants in union life. Only 17.8 per cent of workers said they took part in union activities regularly, whereas 46.2 per cent said they attended union-organised actions occasionally or rarely. Among manual workers the proportions were only slightly better: 20 per cent take part regularly (16.7 per cent ‘whenever possible’, and 3.3 per cent ‘often’). Such a low level of activity could be the result (or the cause) of a certain distance between the union organisation's policy and the opinions of individual workers, at least in Firm A, where only 41.4 per cent of respondents felt that union policies were identical to their own opinions; in Firm B the figure was 71 per cent. In addition 16.3 per cent of employees in A expressed complete antipathy towards their union organisation, expecting nothing at all from it, an attitude shared by 4 per cent of employees in B.

Comparing the situation in Firm A with that in Firm B, where the membership and status of unions is higher but relations with management more problematic, suggests that improved communication with management and superiors, together with the existence of a stabilised production programme and a low risk of redundancies (now that the job cuts associated with fundamental restructuring have been completed), lower the expectations of workers toward unions and act as a disincentive to participation in their activities.

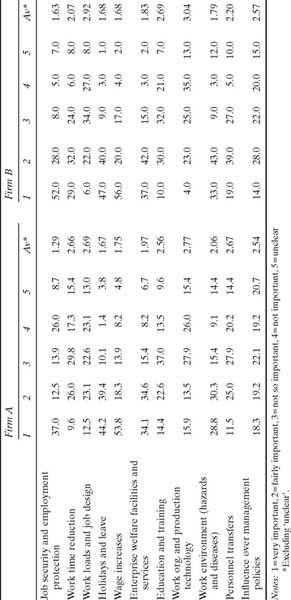

Table 6.6 summarises employees' opinions on what kind of union activities are important at the level of their enterprise: their views largely correspond with contemporary understandings of unions' mission (protection of the worker, social provision) but a residual conception of unions as organisations which organise recreation and free-time activities partially endures. The top priority for union activity is viewed as protection of jobs and employment, followed by holiday provision and leave, securing higher wages and administration of company-based welfare facilities and services. Among manual workers greater accent was laid on both holidays and wages, whilst little priority was accorded activities seen as the domain of immediate superiors and management, such as the organisation of work, production technology, work loads and job design and education and training. Since an important aspect of union activity was repeatedly identified as attention to work conditions, we asked employees what would lead to increased union influence in this area. The overwhelming agreement was that an expansion of union rights was needed, with the second most popular response being ‘greater participation by workers in enterprise management’.

Table 6.6 Priorities for union activity in the firm (per cent)

Conclusions

Our findings reveal a number of problems in the field of human resource management which clearly exist in both firms and which, given obliging external circumstances, could lead to a decline in the loyalty of employee to employer, to the destabilisation of pro-firm attitudes among employees, or to a reduction in professional reliability and an increase in turnover of qualified employees. Some 12 per cent of employees in Firm A and 17 per cent in Firm B were (definitely or possibly) considering a change of job at the time of the research in 2000, with 63 per cent in A and 46 per cent in B (definitely or probably) ruling out this option. One of the complicating factors, however, when considering the causes of the level of potential personnel turnover, is the differing level of unemployment within the districts where each firm is situated: Firm A lies in a district with about average unemployment of 9.5 per cent in 2000,6 whereas the prospects for finding alternative work appeared to be better near Firm B, where unemployment was only 5.6 per cent.

The introduction of team work for manual workers does not resemble its text-book version in either firm. In some respects the measures introduced by their managements have had the opposite effect, limiting some of the key attributes of team work, such as greater independence in determining work content and job design, interdependence of workers' performance or opportunities to acquire new skills. Innovations in the organisation of work involving more complicated work patterns have seemingly influenced the relation of blue-collar workers to managers, co-workers and trade unions. The subdivision of the work collective into small work groups with greater autonomy has often led to greater solidarity both within the group and with management, but weakened ties to unions. Employees take care of their own needs and demands through their immediate bosses and have less recourse to their union organisation. Where good communication between management and workers is combined with a stable production programme and thus job stability, people have lower expectations of unions and feel less need to take part in their activities. Nevertheless it was possible to detect a certain improvement in employees' attitudes to unions in keeping with a generalised trend in Czech society during the late 1990s. As trade unions adapted to a democratic system and a market economy at national, sectoral and local levels, our findings, notwithstanding differences between the two firms, indicate a partial recovery in their relevance to employees' needs.

Notes

1 Our research was undertaken as part of the ongoing project, ‘The Quality of Working Life in the Electronics Industry’, which is coordinated by Shiraishi Tosimasa (Denki Rengo) and Ishikawa Akihiro (Chuo University Tokyo), and whose third phase covered the UK, France, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Spain, Italy, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland and Estonia.

2 Manual professions were chosen because they represent the majority of workers in both firms (58 per cent in Firm A and 56 per cent in Firm B), because they constitute a relatively homogeneous group from the perspective of work content, and because the rate of unionisation among them is highest.

3 Given the low representation of manual employees working in teams (forty in Firm A and ten in Firm B) we did not include team work as a separate criterion for comparison in Table 6.3.

4 World Value Survey, Czech section: 1990 and 1998.

5 The average rate of unionisation in firms where OS KOVO operates was 56 per cent in 1999.

6 Unemployment in the whole district (Chrudim okres) was 10 per cent according to official statistics in 2000, although in the subregion in which Firm A is situated, unemployment was 5.8 per cent. The preceding year, 1999, had been a difficult one in the district, with a number of major employers, such as TRANS-PORTA and TRAMO, going bankrupt. But the district authorities have been extremely proactive in starting up job-creation schemes.

Bibliography

Jakubka, J. (2000) ‘Novela zákoníku práce’, Personální servis,7–8.

Janata, Z. (1998) ‘Formation of a New Pattern of Industrial Relations and Workers' Views on Their Unions: the Czech Case’, in Martin, R., Ishikawa, A., Makó, C. and Consoli, F. (eds) Workers, Firms and Unions. Industrial Relations in Transition, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang: 211–24.

Kosina, M., Vtelenský, L. and Kováf, M. (1998) Nové smery v organizaci práce, Metodika KOVO, Prague: OS KOVO.

KubínkováM. (1999) Ochrana pracovníku — národní studie, Prague: CMKOS.

Rychlý, L. (2000) ‘Sociální dialog — nástroj modernizace sociálního modelu (1)’, Sociální politika,9: 2.