6

Conclusion

In our closing chapter, we revisit where M&A research has gone, and we outline thoughts on where M&A research can make progress.

Where have we gone?

Existing research suggests that M&A offer firms the possibility to adapt to market or technology change by acquiring resources more quickly compared to other alternatives (Capron, 1999; Capron & Hulland, 1999; Swaminathan et al., 2008). Despite different approaches to assess M&A success (Cording et al., 2010; Oler et al., 2008; Zollo & Meier, 2008), M&A often do not live up their potential (Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Homburg & Bucerius, 2006; King et al., 2004). Associated research has examined M&A using financial or economic, strategic management, organizational behavior, and process perspectives (Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Birkinshaw et al., 2000; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999; Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991).

These four schools of thought offer complementary insights (Meglio & Risberg, 2011), but still present a fundamental problem of research evolving on different paths that provide distinct and incremental advances. This is not a new insight, as researchers recognize fundamental gaps in M&A research remain (Barkema & Schijven, 2008; Graebner et al., 2017; Haleblian et al., 2009). Additionally, several scholars identify a fragmentation in M&A research (Bauer & Matzler, 2014; King et al., 2004) with the consequence that potentially important conceptual links are often taken for granted or ignored. Overall, the development of the field is incomplete (Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006; King et al., 2004) with the consequence that research remains confined within established boundaries and leaves new, potentially important insights understudied.

Across the chapters of the book, we argue that organizational change (e.g., Armenakis & Bedeian, 1999) can provide an integrating perspective to help overcome shortcomings of existing M&A research. We believe this approach fits well to acquisition research, as change is part of acquisitions (King, 2006) in that they lead to internal change from combining formerly separated organizations (Cording et al., 2008) and changes to a firm’s external context and relationships (King & Schriber, 2016). Importantly, considering organizational change allows us to provide a broader strategic perspective on acquisition research. This is a necessary step, as an acquisition is not a discrete event (Rouzies et al., 2018), but rather one tool in executing a firm strategy (Achtenhagen et al., 2017) that also effects firm stakeholders.

Organizing acquisition research across the dimensions of organizational change involving content, context, process, and outcome allows us to synthesize research by taking a broader perspective than gap-spotting along established routes (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2013). It also enables avoiding several implicit assumptions of M&A research by identifying broader research problems that might help us to improve our understanding of M&A through applying a more dynamic, integrative, and inclusive perspective of acquisitions as a tool to increase firm competitiveness (Jemison & Sitkin, 1986) and survival. Our approach answers calls for a dynamic and procedural perspective on M&A (Meglio & Risberg, 2010; Jemison & Sitkin, 1986), as well as identified needs for an integrated framework or perspective of M&A (Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999: Rouzies et al., 2018). Thus, we argue that future research should leave well-trodden paths to rethink common and established research domains, designs, and data sources (i.e., Meglio & Risberg, 2010). Even though integrative perspectives on M&A (Steigenberger, 2017; Bauer & Matzler, 2014) and new methodological approaches have been used (e.g., Tienari, Vaara, & Björkman, 2003; Graebner, 2004), we and others argue a clear need of “asking bigger, better, and more challenging questions” remains (e.g., Birkinshaw, Healey, Suddaby, & Weber, 2014, p. 38).

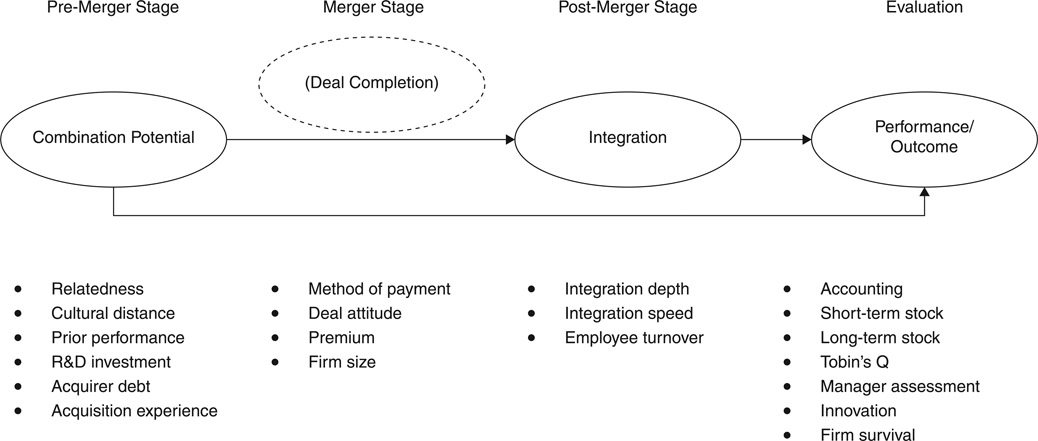

When summarizing Chapter two to Chapter five, the lowest common denominator in M&A research is the recognition that there are various issues driving acquisitions, different phases, and interdependencies of the different phases, see Figure 6.1. Except for the deal completion stage that is widely ignored, research has examined phases separately and either focused on external or internal contexts. Still, research consistently examines the effectiveness of M&A using financial or other measures of M&A outcomes. While progress has been made through reviews (Calipha, Tarba, & Brock, 2010; Graebner et al., 2017; Haleblian et al., 2009; Schweiger & Goulet, 2000; Steigenberger, 2017) and meta-analysis of prior research (Homberg et al., 2009; King et al., 2004; Stahl & Voigt, 2008), observed failure rates of M&A have not improved over recent decades creating “a puzzle for academics and practitioners” (Capasso & Meglio, 2005, p. 219).

Figure 6.1 Lowest common denominator of M&A research

In evaluating why M&A performance outcomes have not improved, one possible explanation is that management research does not have a meaningful impact on management practice (Birkinshaw et al., 2014; Cartwright & Schoenberg, 2006), and there are two possible causes. First, scholars have long recognized poor knowledge-dissemination efforts of researchers and universities (Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001; Vermeulen, 2005). Second, it might be caused by the irrelevance of research to managers (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2013). This points to the need to complement different perspectives, and to avoid the investigation of isolated effects that relates to the “streetlight” effect. This effect is illustrated by the joke about a drunk looking for his lost car keys not where he knows he lost them but by a streetlight where he is able to see. As a result, we believe progress in understanding M&A likely requires challenging of its basic underlying assumptions of current M&A research to enable examination of the wider context surrounding an acquisition.

Specifically, we challenge the assumption that a set or combination of success-factors makes all M&A work, as success-factors from one context may not work in another. This builds on the insight that M&A are highly complex events, and this complexity places boundaries around the ability to generalize research results. For example, the external context often differs making solutions viable only under particular environmental conditions. This is in line with recent research questioning dichotomies of beneficial and detrimental aspects of research constructs that recognizes the importance of context (e.g., Bauer, Dao, Matzler, & Tarba, 2017; Zaheer et al., 2013). We believe this can help to explain that, when research results are aggregated in a meta-analysis, the results are often non-significant (e.g., King et al., 2004). In other words, the impact of a construct in different contexts may cancel each other out when they are aggregated. An implication is that M&A research focused on different domains runs the risk of trying to compare the incomparable. We argue a solution to address increasing complexity comes from considering the four domains of change. In other words, research needs to recognize the importance of broader frames to allow detecting broader, multi-level patterns in M&A.

Where can we go?

When looking at the theoretical arguments of the most common M&A success-factors, individual studies often conflict. Attempts at integration suggest that factors interact with each other or that they are dependent on each other (e.g. Larsson & Finkelstein, 1999; Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Zaheer et al., 2013). There likely are several additional reasons for mixed research findings. First, diverging results can be attributed to the “too much of a good thing effect” where direct effects can become insignificant or turn out to be negative due to curvilinear effects from context-specific differences (Pierce & Aguinis, 2011). Second, there might also be a vast body of research correctly reflecting actual phenomena, but they do not find significant relationships and remain unpublished due to “non-results” experiencing lower publication likelihood (Bettis, Ethiraj, Gambardella, Helfat, & Mitchell, 2016). Third, many factors may involve “examples or management folklore, i.e., stories, customs, and beliefs that lack empirical confirmation” (Hubbard, Vetter, & Little, 1998, p. 244), and replication studies remain rare (Bettis et al., 2016).

Importantly, we argue that a fourth reason for the mixed results in M&A research relates to underlying assumptions that limit the scope of investigation. In other words, researchers are confined by applied concepts and examined relationships, as well as current research that influences decisions on what is worthwhile to examine. The overall implication drives the need for a box-breaking perspective on M&A research (cf. Alvesson & Sandberg, 2014). We begin this process by outlining implicit assumptions, involving: 1) the comparability of individual M&A, 2) the examination of M&A in isolation, 3) the need to consider different M&A phases together, and 4) the assessment of M&A performance.

Change content: comparability of M&A

A crucial point in research attempting to establish the drivers of M&A performance is to compare acquisitions, but most M&A research is cross-sectional. In other words, research compares firms that make acquisitions against each other on criteria included in a study across different years, industries, etc. This involves comparison of acquisitions that are similar and those that are not. The assumption is that a sufficient number of M&A will cancel out differences and allow a statistically significant average effect to appear. While we do not disagree with this method and we have used it ourselves, we are concerned the unit of analysis can downplay important differences in motives with different performance implications. Bower (2001) previously raised this concern, but underlying research practices remain largely unchanged.

For example, most research on M&A performance considers very broad categories, such as strategic fit or complementarity (Hitt et al., 2009), or integration depth or autonomy granted to the target (Puranam et al., 2009: Zaheer et al., 2013). Consequently, acquisition research implicitly builds on the assumption that acquirers share similar goals to make the specific items of interest comparable. However, this may gloss over important differences. For instance, while resource overlaps are generally associated with beneficial cost reductions in competitive landscapes favoring low costs (Capron, Dussauge, & Mitchell, 1998), cost reductions may have other, contradictory performance effects. For instance, they can hamper firm responsiveness to sudden increases in demand (Shaver, 2006). This can have serious effects on the usefulness in comparing what outwardly may appear similar characteristics.

Further, we argue that organizations are path-dependent unique bundles of resources and capabilities (Williamson, 1999). This is highly relevant to M&A, as they are an important tool for business reconfiguration of resources (Karim & Mitchell, 2000). For example, firms with increased acquisition activity display increased survival rates (Almor et al., 2014). Still, firm characteristics associated with strategy, structure, and culture are relatively stable (Pettigrew, 1979), and determine how firm activities are executed and fit with a firm’s environment (e.g., Zheng, Yang, & McLean, 2010). As a result, acquisition behavior develops over time and differs from firm to firm, or it requires considering what makes acquisitions similar. Again, not all acquisitions are alike (Bower, 2001), but research generally continues to treat all acquisitions and acquirers as the same. The effect is a continued search for an average may gloss over important findings appearing when considering differences between firms and their context.

Adopting a temporal perspective enables going beyond the examination of M&A as individual events to view them as a tool for continuous adaption and corporate development (e.g., Achtenhagen, et al., 2017; Barkema & Schijven, 2008) and as such, as a part of the firm´s strategy (King et al., 2018). Developed patterns can foster competitive advantages that ensure long-term growth and economic stability contributing to sustained corporate development (López, Garcia, & Rodriguez, 2007). For instance, Brueller and colleagues (2016) suggest different integration approaches to human resources in M&A that may all be useful under different conditions. Consequently, to make acquisitions and their outcomes comparable, research needs to consider topics like the involved firm histories, target selection processes, integration planning, decisions, and execution abilities in sample construction. For example, Cuypers et al. (2017) find that target firm acquisition experience matters.

In addition to accounting for the influence of involved firms’ histories, it might be worthwhile to also consider the future of the combined organization. Based on the idea that a firm is a unique individual bundle of resources and capabilities, some resources and capabilities must be shared and transferred between the acquiring and target organizations to achieve the desired outcomes (Birkinshaw et al., 2000). In addition to changing a target firm, these resource and capability transfers also likely change an acquirer (Clark & Geppert, 2011; Sarala, Junni, Cooper, & Tarba, 2016). Further, this is an implicit assumption behind measuring acquiring firm performance. However, challenges of managing increased size in terms of annual sales and employees, and associated changes in the organizational structure, leadership styles, coordination demands, and organizational practices (Matzler, Uzelac, & Bauer, 2014) are not consistently considered (Lamont et al., 2018). Additionally, growth modes are likely to change over time (Achten-hagen et al., 2017), suggesting the need to consider the pace or frequency of acquisitions. While firms can alter their behavior over time, each acquisition shapes a firm’s experience. While the insight acquirer organizations are influenced to varying degrees by M&A is not new (Marks & Mirvis, 1998), it has had insufficient impact on research. We hold that future acquisition research needs to consider the changes for the combined organization in terms of culture, structure, and strategy. This becomes even more relevant for serial acquirers pursuing acquisitive growth. One can easily assume that the content of change has dramatically evolved for firms like Assa Abloy or DSV transportation and logistics (Secher & Horley, 2018), or General Electric.

Change context: can M&A be examined in isolation?

As already developed, M&A research largely focuses on individual acquisitions, and this may unnecessary limit M&A theory. For example, M&A research has been intensely concerned with the involved firms to examine: employees, cultures, identities, and other aspects of combining organizations. However, external and internal change surrounding an acquisition is often ignored. For example, market factors, such as competitors, customers, and other stakeholders are implicitly assumed to have a similar impact across different acquisitions. Additionally, managers have responsibilities beyond an acquisition (Puranam et al., 2006) or implement overlapping processes of integration, crisis management and operations (Rouzies et al., 2018). Nonetheless, various stakeholders of an acquisition or an acquiring firm are often ignored, even though they may influence M&A outcomes. This is of special interest for various stakeholders that display conflicting interests and create internal and external tensions to make M&A success more difficult. For example, a M&A boutique might not be interested in the best deal for the acquiring firm, but rather interested in the maximum possible bonus from a higher premium. In other words, advisors come with agency problems. Additionally, in countries with strict labor regulations, members of the union have greater involvement with acquisitions that can also trigger government involvement. In effect, despite several notable exemptions (e.g. Capron & Guillén, 2009), research may consistently downplay the effect of a range of contextual factors.

An acquisition can radically reformulate firm strategies and impact internal and external stakeholders with different motivations and capabilities to respond. Criticism on the nearly exclusive deal focus of research is not new (Teerikangas & Joseph, 2012), and M&A researchers started to acknowledge the importance of internal stakeholders, as well as the external environment, including customers (Kato & Schoenberg, 2014; Rogan & Greve, 2014) and competitors (Clougherty & Duso, 2009; Keil et al., 2013). Still, consideration of stakeholders needs to account for changing environments (Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, & Lampel, 1998), as the importance of stakeholders varies with an organization’s lifecycle (Jawahar & McLaughlin, 2001). Further, there is some evidence that early movers in acquisition waves outperform others (Haleblian et al., 2012), or that the industry lifecycle determines appropriate integration strategies (Bauer et al., 2017). Nonetheless, M&A research is still dominantly focused along the stages of a specific M&A process for combining organizations without consideration of external stake-holders and conditions to treat M&A as isolated events.

There is a clear need for M&A research to explicate how M&A affects surrounding stakeholders, drives industrial change and competitor responses, or even contributes to larger shifts in society. For example, Amazon’s proposed purchase of Whole Foods lowered the market capitalization of competing grocery companies by $40 billion (Domm & Francolla, 2017). Thus, M&A can be seen as triggering industry shifts. This is consistent with current observations of industrial conglomerates that use M&A to dramatically change their existing businesses (e.g., General Electric, IBM or Siemens). As a result, M&A influence both acquiring firm performance and the performance of other firms in impacted industries. This is important given recent advances in information technology, robotics, additive manufacturing, and other areas often considered as having the potential for profound change in industrialized countries. As each acquisition is affected but also affects the internal and external context of involved firms, it would be highly relevant to investigate corresponding contingencies and relationships.

Change process: M&A phases

M&A research has acknowledged the importance of a process perspective on acquisitions. Since the seminal paper from Jemison and Sitkin (1986), several authors highlighted the importance of the acquisition process and associated it with a need for a methodological rejuvenation of the field (Meglio & Risberg, 2010). Until now, there is general agreement that the acquisition process consists of three phases that contain various activities and that are interrelated with each other (Bauer & Matzler, 2014). For example, acquisition characteristics, such as strategy formulation, target screening, evaluation and due diligence, negotiation, deal closing, and integration (see also Chapter 4), are likely interdependent. This is relevant for the understanding of M&A outcomes.

As previously stated, most M&A research uses a cross-sectional perspective that focuses on a specific stage of the process generating a rather static and abstract view on acquisitions. For example, integration is commonly assessed as a finally achieved or desired degree of integration (e.g. Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Cording et al., 2008) without considering the inherent tasks that might be organized differently among different firms and for different types of acquisitions. Again, the idea is that a sufficient number of observations cancels out the differences and leads to significant results. Here, several advancements have been made and quantitative research has begun to examine antecedents of appropriate integration approaches in terms of similarity and complementarity (e.g. Zaheer et al., 2013), contingencies such as the industry lifecycle determining appropriate integration approaches (Bauer et al., 2018), or intermediate goals reducing causal ambiguity during integration (Cording et al., 2008). A more detailed perspective can be found in the qualitative work from Brueller and colleagues (2016) that consider different acquisition types and identify distinct HR integration strategies. Despite these progresses, a general implicit assumption that generic or common acquisition processes from applying cross-sectional analysis can identify paths to acquisition success. This has contributed to acquisition failures often being attributed to “soft factors,” such as cultural issues, and success being attributed to managers (Graebner et al., 2017).

However, the acquisition process is full of paradoxes and what might cause success in one case can lead to failure in another, or acquisitions highly differ from each other (Bower, 2001; Campbell et al., 2016). This also refers to the content and context of change, or ideas developed in this book. A firm’s acquisition logic, history, strategy, structure, and culture determine organizational choices toward acquisition approaches. We cannot assume that an opportunistic acquirer organizes the process similar to a firm with a dedicated M&A function or a deliberate acquisition strategy. Still, the costs of knowledge codification or a dedicated M&A function might exceed its benefits for an infrequent acquirer that will approach the acquisition process differently. Different approaches are also likely required for different targets. For example, there is evidence that highly innovative targets should not be disrupted with structural changes (Puranam et al., 2009) that are important in cost-driven acquisitions (Capron, 1999). As a consequence, there is no single pertinent acquisition approach. Instead, there are multiple approaches consisting of combinations of different conditions and activities suitable in specific situations. We believe that investigating the dynamism of the process in general and identifying different pathways or combinations of activities to success by considering multiple paradoxes displays a fruitful avenue for future research and for our gain of knowledge.

Change outcome: M&A and performance

While most M&A research deals with the question on how to make successful acquisitions, there is an ongoing debate on how to assess M&A performance (see Chapter 5). While there is agreement on the disappointing success rates of acquisitions (e.g., Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Homburg & Bucerius, 2005, 2006; King et al., 2004), any relationship to the motives behind an acquisition (see Chapter 2) are largely overlooked in acquisition research. While research generally assumes acquisitions are made to improve performance, there are multiple motives for an acquisition. Further, not all motives may necessarily lead to improved performance, such as blocking a rival’s access to resources. Additionally, the acquisition of an R&D intense target firm “distorts the earnings and book values” (Franzen, Rodgers, & Simin, 2007, p. 2931) making accounting measures of performance less relevant. Still, three distinct approaches are generally used to assess M&A performance, stock market, accounting, or survey measures, and research using multiple measures of performance is needed.

Stock market financial measures of acquisition performance are the most common (King et al., 2004). Stock market measures are future-oriented, but they only apply to publicly listed firms that represent only a minor share of all firms conducting acquisitions. Further, this approach is rather unidimensional and other “potentially relevant dimensions of firm performance” are not covered by stock market measures (King et al., 2004, p. 196). Additionally, short-term event studies do not capture integration needed for value creation (Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991), and “at best predict it” (King et al., 2008).

The use of accounting measures to evaluate performance also has shortcomings, including possible manager manipulation, a historical focus, and undervaluation of intangible assets (Rowe & Morrow, 1999; Trahms et al., 2013). Accounting measures of performance are narrow, and they only gauge economic performance (Papadakis & Thanos, 2010). For example, accounting measures do not include an assessment of risk (Lubatkin & Shrieves, 1986). Another concern is that industry can help to explain accounting performance (Brush et al., 1999), driving the need to control for industry (e.g., Dess et al., 1990; Stimpert & Duhaime, 1997) that is often absent in acquisition research (Meglio & Risberg, 2011). Additionally, accounting measures often cannot be compared across different countries and industries (Weetman & Gray, 1991), as valuation-rules systematically vary across different institutional settings (Leuz, Nanda, & Wysocki, 2003; Basu, Hwang, & Jan, 1998).

Surveys to obtain managerial assessment cover the multidimensionality of M&A performance (Capron, 1999; Cording et al., 2010), but they come with concerns of common method (MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012) or key informant bias (Kumar, Stern, & Anderson, 1993). Even if bias is not intended, human memory tends to evaluate past events better than they actually were (Golden, 1992), and the capacity of recollection of discrete events decreases exponentially (Sudman & Bradburn, 1973).

Different measures of M&A performance share little variance (Cording et al., 2010) and no single measure is able to address the multidimensionality of firm performance (Richard et al., 2009). While research agrees that M&A failure rates can be reduced, the time needed to improve performance likely varies, and short-term measures offer only predictions of actual performance changes. Nonetheless, we implicitly assume that we can assess M&A performance and compare these among firms as discrete events bracketed in time.

While most scholars agree that M&A can be understood from a process perspective (e.g., Haspeslagh & Jemison, 1991; Jemison & Sitkin, 1986; Birkinshaw et al., 2000), the insight that acquisitions are processes enacted in a broader, continuously evolving context has only been considered relatively recently. For example, Shi et al. (2012) point to the consequences of considering acquisitions as processes taking place in ongoing processes of societal and industrial change, or Rouzies and colleagues (2018) developing how acquisitions require managing co-evolving processes. Still, this insight is insufficiently reflected in current research with only a few exceptions (e.g., Kato & Schoenberg, 2014; Keil et al., 2013). This suggests an increased need to consider additional performance measures and examining how they compare.

Several existing studies go beyond common performance measures, and they can serve as exemplars. For example, Cording and colleagues (2008) consider the impact of intermediate goals on improving performance. Additionally, Zollo and Meier (2008) highlight three different performance levels: task performance, transaction performance, and combined entity firm performance. Research also considers innovation performance following acquisitions (Bauer et al., 2016; Kapoor & Lim, 2007; Puranam et al., 2006), or changes in learning orientation (e.g., Dao, Strobl, Bauer, & Tarba, 2017). Further, recent research suggests that M&A are complemented by other growth modes like organic growth (Achtenhagen et al., 2017) and co-evolving processes (Rouzies et al., 2018), that may influence M&A performance. This reinforces the need to theoretically derive the selection of performance measures (Cording et al., 2010) and to use multiple measures of performance to enable comparison of research findings. As each measure offers certain strengths and weaknesses, a fuller picture of M&A performance may benefit from more holistic and integrative approaches to M&A outcomes.

If M&A are a tool for firms to adjust to past, current, and anticipated events (Almor et al., 2014; Barkema & Schijven, 2008), then acquisition success may be better understood by considering an acquisition event with industry acquisition activity (Laamanen & Keil, 2008). Another consideration is the impact of an acquisition on a firm’s capability to adapt for long term-firm survival. For example, acquisition experience that codifies learning into routines may build an acquisition capability (Barkema & Schijven, 2008) helping firms to improve the survival rate by strengthening or change their competitive advantage.

The preceding points highlight a divide between research taking a strategic and a financial perspective. Strategic measures generally take a long-term perspective because of path-dependencies and resource scarcity creating lock-in effects from future decisions. In contrast, financial perspectives often apply short-term measures. While share prices adjust to reflect firm events (Fama, 1970; McWilliams & Siegel, 1997), many M&A event studies consider a window of only one or a few days around M&A announcement. Meanwhile, additional information about an acquisition and its implementation unfolds over time making short-term performance measures more useful indicators of the direction (positive or negative) of acquisition performance (King et al., 2008). Additionally, a positive acquirer share price effect typically becomes significantly negative after 22 days (King et al., 2004), illustrating share prices surrounding acquisition include short-term speculation. Further, the success of firm strategies requires comparison to industry peers or alternate investments.

Summary and outlook

Our review of current M&A research was driven by concerns that the rapid growth of the field is paired with path-dependencies. The effect is silos where scholars pursue studies in common areas that often ignore related areas of research. While this could be discouraging, we see it as providing several promising paths for M&A research. We attempt to provide a fresh, change-oriented perspective that integrates past research to identify promising avenues of future research. While our review covers a substantial part of M&A research, we recognize there are aspects not given full recognition due to our focus on research relevant to organizational change. Again, we anticipate this offers a more integrative approach for future research.

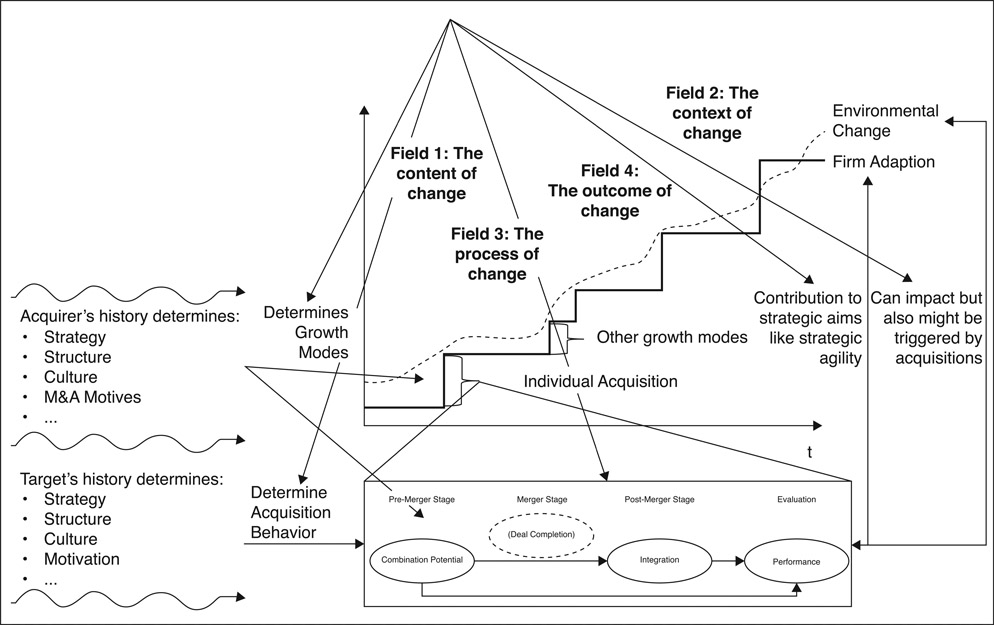

Long-term corporate success and sustainable firm development requires constant change, as firms adapt their resources and capabilities to meet a changing environment (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). For adaptation, firms can pursue with organic (internal) and non-organic (external) strategies. While both can occur in parallel (Achtenhagen et al., 2017; McKelvie & Wiklund, 2010), the choice is often treated as a dichotomy (Lockett, Wiklund, & Davidson, 2011). From a strategic and organizational perspective, this leads to a call for a different approach to acquisition research summarized in Figure 6.2. Overall, four broad research directions according to the reviewed change domains to: 1) extend existing acquisition performance measures with long-term strategic corporate success measures, 2) view acquiring and target firms as highly individual and subject to constant change, 3) consider how acquisitions shape and are shaped by the context, and 4) investigate combinations of activities and sub-processes that might lead to success or failure.

Existing acquisition success measures range from financial, accounting, survey-based, to combinations of the former ones (Cording et al., 2010; Zollo & Meier, 2008). Even though these measures have been criticized for sharing little variance with each other (Cording et al., 2010) and the overall construct of M&A performance is ambiguous (Meglio & Risberg, 2011), we acknowledge progress has been made in developing more fine-grained and detailed measures of specific facets of M&A success (e.g. innovation outcomes, intermediate goals). Still, acquisition performance needs to align with corporate strategy of adapting a firm’s portfolio of businesses that can support strategic agility, or a firm’s renewal and flexibility (Goldman, Nagel, & Preiss, 1995; King et al., 2018). For example, strategic agility has recently been applied as a component of the entire M&A process (Junni et al., 2015). Thus, it is likely relevant to investigate how an individual acquisition contributes not only to financial measures, but also to the development of dynamic capabilities that are relevant for long-term firm survival. As a result, future research is needed to investigate how organic, hybrid, and acquisitive growth modes contribute to a firm’s strategy.

Second, firms are unique bundles of resources and capabilities that need management involvement to achieve competitive advantage (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003). This requires acknowledging that capabilities develop over time or display path dependency (Ahuja & Lampert, 2001; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Vergne & Durand, 2011). Consequently, we claim that prior to a focal acquisition, both an acquirer’s and a target’s history matter. For example, a target firm’s acquisition experience can mitigate advantages of acquirer experience (Cuypers et al., 2017). The history and path-dependence of a firm finds is expressed in its organizational culture, structure, and strategy. Further, firms might have some M&A specific experiences and histories that

Figure 6.2 Future research fields

influence acquisition decisions from interpretation of past experience that informs decision-making heuristics (Bingham, Eisenhardt & Furr, 2007; Gersick & Hackman, 1990; Zollo & Winter, 2002). Consequently, strategic actions are embedded in historically developed processes and a firm’s history might help us in understanding organizational strategies (Vaara & Lamberg, 2016). This suggests that observed acquisitions are limited to a large extent by an acquiring firm’s motives and logic by driving target screening procedures, method of payment, integration planning, and other decisions. Firm history will also likely drive target firm reactions to an acquisition announcement. Research into this area and associated questions is largely open to path breaking research.

Third, acquisitions effect combining firms and firms beyond them. Acquisitions occur within an environment with different stakeholders and motivations for acquisitions. In other words, unintended effects of acquisitions often include changing relationships with stakeholders. As a result, an acquisition can influence or be influenced positively or negatively by the external and internal environment of a firm. For example, an acquisition can contribute to an acquisition wave, or stakeholders, such as government regulators, can preclude the completion of acquisitions for events not directly related to a deal. For example, Chinese regulators killed Qualcomm’s $44 billion acquisition of NXP, a semiconductor firm, in what has been attributed to trade tensions between the U.S. and China (Tibken, 2018). As a result, research may need to broaden criteria and controls for evaluating acquisitions and their completion and outcomes. Further, this has implications for comparing acquisitions across institutional frameworks (Capron & Guillén, 1999; Bauer et al., 2018) and industry lifecycles (Bauer et al., 2018) that can substantially impact acquisition outcomes.

The previous issues impact how research can investigate acquisition processes beyond common calls for more process research. In line with these calls, we hold that instead of searching for one pertinent approach, research should start with combinations of actions or sub-processes across acquisition phases to identify configurations (e.g. Campbell et al., 2016) of acquirer behavior and outcomes. Combined with the suggestions to consider content, context, and associated outcomes future research might result in integrative and more impactful results. We integrate often competing perspectives of acquisitions within research on organizational change (content, context, process, and performance outcomes). As part of this reframing, we recognize that many aspects of acquisitions intertwine across these boundaries and that often overlooked interfaces between dominant M&A perspectives represent fruitful avenues of research. In the end, we hope that we could stimulate future research activity in the fascinating field of M&A.