Data gathering

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Four key issues

7.3 Data recording

7.4 Interviews

7.5 Questionnaires

7.6 Observation

7.7 Choosing and combining techniques

7.1 Introduction

This chapter presents some techniques for data gathering which are commonly used in interaction design activities. In particular, data gathering is a central part of identifying needs and establishing requirements, and of evaluation.

Within the requirements activity, the purpose of data gathering is to collect sufficient, accurate, and relevant data so that a set of stable requirements can be produced. Within evaluation, data gathering is needed in order to capture users' reactions and performance with a system or prototype.

In this chapter we introduce three main techniques for gathering data. (Some additional techniques relevant only to evaluation are discussed in Chapters 12–15.) In the next chapter we discuss how to analyze and interpret the data collected. These three techniques are interviews, questionnaires, and observation. Interviews involve an interviewer asking one or more interviewees a set of questions which may be highly structured or unstructured; interviews are usually synchronous and are often face-to-face, but they don't have to be. Questionnaires are a series of questions designed to be answered asynchronously, i.e. without the presence of the investigator; these may be on paper, or online. Observation may be direct or indirect. Direct observation involves spending time with individuals observing activity as it happens. Indirect observation involves making a record of the user's activity as it happens to be studied at a later date. All three techniques may be used to collect qualitative or quantitative data.

Although this is a small set of basic techniques, they are flexible and can be combined and extended in many ways. Indeed it is important not to focus on just one data gathering technique but to use them flexibly and in combination so as to avoid biases which are inherent in any one approach.

The way in which each technique is used varies depending on the interaction design activity being undertaken. More detailed descriptions of how the different techniques are used within specific activities of the lifecycle are given in later chapters (Chapter 10 for requirements, and Chapters 12–15 for evaluation). Here we give some basic practical information about each technique.

The main aims of the chapter are to:

- Discuss how to plan and run a successful data gathering program.

- Enable you to plan and run an interview.

- Enable you to design a simple questionnaire.

- Enable you to plan and execute an observation.

7.2 Four Key Issues

Data gathering sessions need to be planned and executed carefully. Specific issues relating to the three data gathering techniques are discussed in the following sections, but first we consider four key issues that require attention for a data gathering session to be successful. These four issues are goal setting, the relationship between the data collector and the data provider, triangulation, and pilot studies.

7.2.1 Setting Goals

The main reason for gathering data at all is to glean information about something. For example, you might want to understand how technology fits into normal family life, or you might want to identify which of two icons representing a ‘send email’ action is easier to use, or you might want to find out whether the redesign you are planning for a hand-held meter reader is along the right lines. There are many different reasons for gathering data, and before beginning it is important to identify specific goals for the particular study. The goals that are set will influence the nature of the data gathering sessions, the data gathering techniques to be used, and also the analysis to be performed. Once the goals have been set, then you can concentrate on what data to look for and what to do with it once it is gathered.

The goals may be expressed more or less formally, e.g. using some structured or even mathematical format, or using a simple description such as the ones in the previous paragraph, but whatever the format they should be clear and concise. In interaction design it is more usual to express the goals of data gathering more informally.

7.2.2 The Relationship with Participants

One significant aspect of any data gathering is the relationship between the person (people) doing the gathering and the person (people) providing the data. Making sure that this relationship is clear and professional will help to clarify the nature of the study. One way in which this can be achieved is to ask participants to sign an informed consent form. The details of this form will vary, but it usually asks the participant to confirm that the purpose of the data gathering and how the data will be used has been explained to them and that they are happy to continue. It also often includes a statement that the participant may withdraw at any time, and that in this case none of their data will be used in the study.

It is common practice in many countries to use an informed consent form when running evaluation sessions, particularly where the participants are members of the public, or are volunteers in a research project (see Box 13.2). In this case, the informed consent form is intended to protect the interests of both the data gatherer and the data provider. The gatherer wants to know that the data she collects can be used in her analysis, presented to interested parties, and published in reports (as appropriate). The data provider wants reassurance that the information he gives will not be used for other purposes, or in any context that would be detrimental to him. This is especially true when disadvantaged groups such as disabled people or children are being interviewed. In the case of children, using an informed consent form reassures parents that their children will not be asked threatening, inappropriate, or embarrassing questions, or be asked to look at disturbing or violent images. In these cases, parents are asked to sign the form.

However, this kind of consent is not generally required when collecting data for the requirements activity where a contract already exists in some form between the data collector and the data provider. For example, consider the situation where a consultant is hired to gather data from a company in order to establish a set of requirements for a new interactive system to support timesheet entry. The employees of this company would be the users of the system, and the consultant would therefore expect to have access to the employees to gather data about the timesheet activity. In addition, the company would expect its employees to cooperate in this exercise. In this case, there is already a contract in place which covers the data gathering activity, and therefore an informed consent form is less likely to be required. As with most ethical issues, the important thing is to consider the situation carefully and make a judgment based on the specific circumstances.

Similarly, incentives for completing a questionnaire might be needed in some circumstances because there is no clear and direct advantage to the respondents, but in other circumstances, respondents may see it as part of their job to complete the questionnaire. For example, if the questionnaires form part of the requirements activity for a new mobile sales application to support sales executives, then it is likely that sales executives will complete a questionnaire about their job if they are told that the new device will impact on their day-to-day lives. In this case, the motivation for providing the required information is clear. However, if you are collecting data to understand how appealing is a new interactive website for school children, different incentives would be appropriate. Here, the advantage for the individuals to complete a questionnaire is not so obvious.

7.2.3 Triangulation

Triangulation is a strategy that entails using more than one data gathering technique to tackle a goal, or using more than one data analysis approach on the same set of data. For example, using observation to understand the context of task performance, interviews to target specific user groups, questionnaires to reach a wider population, and focus groups to build a consensus view is one example of a triangulated data gathering program. Triangulation provides different perspectives and corroboration of findings across techniques, thus leading to more rigorous and defensible findings.

7.2.4 Pilot Studies

A pilot study is a small trial run of the main study. The aim is to make sure that the proposed method is viable before embarking on the real study. Data gathering participants can be (and usually are) very unpredictable, even when a lot of time and effort has been spent carefully planning the data gathering session. Plans for a data gathering session should be tested by doing a pilot study before launching into the main study. For example, the equipment and instructions that are to be used can be checked, the questions for an interview or in a questionnaire can be tested for clarity, and an experimental procedure can be confirmed as viable. Potential problems can be identified in advance so that they can be corrected. Distributing 500 questionnaires and then being told that two of the questions were very confusing wastes time, annoys participants, and is an expensive error that could have been avoided by doing a pilot study.

If it is difficult to find people to participate or if access to participants is limited, colleagues or peers can be asked to comment. Getting comments from peers is quick and inexpensive and can be a substitute for a pilot study. It is important to note that anyone involved in a pilot study cannot be involved in the main study. Why? Because they will know more about the study and this can distort the results.

Box 7.1: Data Versus Information

There is an important difference between data and information. Data is a collection of facts from which conclusions may be drawn, while information is the result of analyzing and interpreting the data. For example, you might want to know whether a particular screen structure has improved the user's understanding of the application. In this case, the data collected might include the time it takes for a set of users to perform a particular task, the users’ comments regarding their use of the application, biometric data about the users’ heart rate while using the application, and so on. At this stage, all you have is data. In order to get to information, the data needs to be analyzed and the results interpreted. That information can then feed into the requirements or evaluation activity.

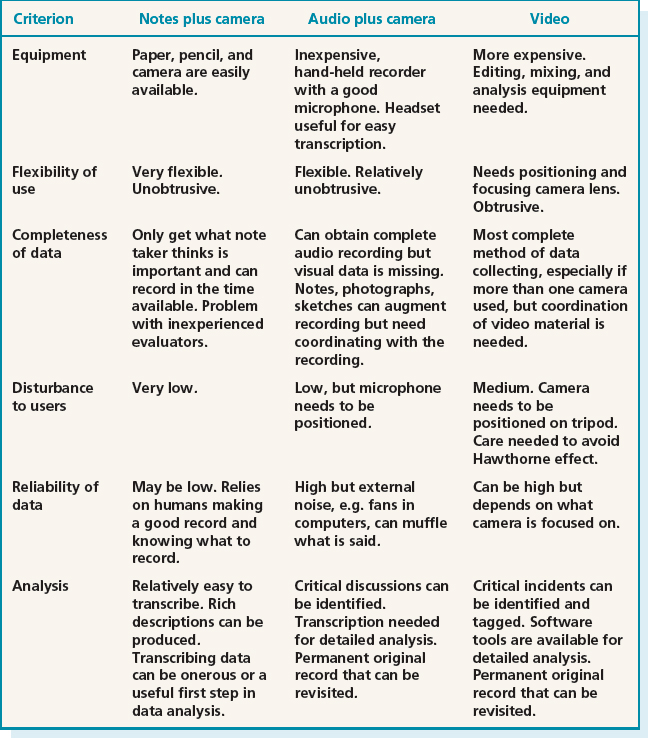

7.3 Data Recording

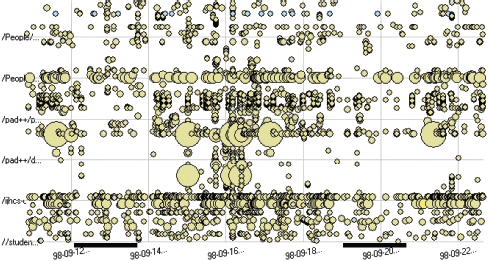

The most common forms of data recording are taking notes, audio recording, taking photographs, and video recording. These may be used individually or in combination. For example, an interview may be audio recorded and then to help the interviewer in later analysis, a photograph of the interviewee may be taken. Digital still cameras are especially useful as they provide an image immediately and the photograph can be re-taken if necessary. Digicams are also increasingly used to record data directly onto a disk that can be downloaded into a computer package such as iMovie or Premiere. This is much easier, cheaper and more convenient than using analog video cassettes. Questionnaires are usually completed by the participant and therefore are ‘self-documenting’, i.e. no further data recording needs to be arranged. Participant diary studies are also self-documenting, and interaction logs are usually generated automatically (see Section 7.6.3 for more details). Which data recording techniques are used will depend on the context, time available, and the sensitivity of the situation; the choice of data recording techniques will have an impact on how intrusive the data gathering will be. In most settings, audio taping, photographs, and notes will be sufficient. In others it is essential to collect video data so as to record in detail the intricacies of the activity and its context. Three common data recording approaches are discussed below.

7.3.1 Notes Plus Still Camera

Taking notes is the least technical way of recording data, but it can be difficult and tiring to write and listen or observe at the same time. It is easy to lose concentration, biases creep in, handwriting can be difficult to decipher, and the speed of writing is limited. Working with another person solves some of these problems and provides another perspective. Handwritten notes are flexible in the field or in an interview situation but must be transcribed. However, this transcription can be the first step in data analysis, as the data will be reviewed and organized. A laptop computer can be used instead of handwritten notes, but it is more obtrusive and cumbersome. Even a PDA with keyboard can be distracting because of the key clicks; paper and pen seem to be almost invisible. Digital images or documents can be easily collected (provided permission has been given). If a record of other images and documents is needed, photographs or sketches can be captured.

7.3.2 Audio Plus Still Camera

Audio recording can be a useful alternative to note taking and is less intrusive than video. In observation, it allows observers to be more mobile than with video cameras, and so is very flexible. In an interview, it allows the interviewer to pay more attention to the interviewee rather than be trying to take notes as well as listen. Transcribing a lot of audio data is time-consuming, which may seem daunting, but it isn't always necessary to transcribe all of it—often only sections are needed. Many studies do not need a great level of detail, and instead, recordings are used as a reminder and as a source of anecdotes for reports. It is also surprising how evocative it can be to hear audio recordings of people or places where you have been. If using audio recording as the main or only technique then it is important that the quality is good. It should be checked before the sessions starts.

As above, audio recording can be supplemented with still photographs of artifacts, events, and the environment.

7.3.3 Video

Video has the advantage of capturing both visual and audio data but can be intrusive.

A further problem with using video is that attention becomes focused on what is seen through the lens. It is easy to miss other things going on outside of the camera view. When recording in noisy conditions, e.g. in rooms with fans or air conditioning running or outside when it is windy, the sound can easily get muffled. It is also important to check that the tape is rewound to the beginning, the camera switched on and the lens cap removed.

Imagine you are a consultant who is employed to help develop a new computerized garden planning tool to be used by amateur and professional garden designers. Your goal is to find out how garden designers use an early prototype as they walk around their clients' gardens sketching design ideas, taking notes, and asking the clients about what they like and how they and their families use the garden. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the three approaches to data recording discussed above, in this environment?

Comment

Handwritten notes do not require specialist equipment. They are unobtrusive and very flexible but difficult to do while walking around a garden. If it starts to rain there is no equipment to get wet, but notes may get soggy and difficult to read (and write!). Video captures more information, e.g. the landscape, where the designers are looking, sketches, comments, etc., but it is more intrusive and you must hold the camera. It is also difficult if it starts to rain. Audio is a good compromise, but integrating sketches and other artifacts later can be more burdensome.

Garden planning is a highly visual, aesthetic activity, so it would be important to supplement note taking and audio recording with a still camera.

Such simple checks can go a long way to ensure valuable data is recorded—it is easy to accidentally overlook something in the stress of the moment.

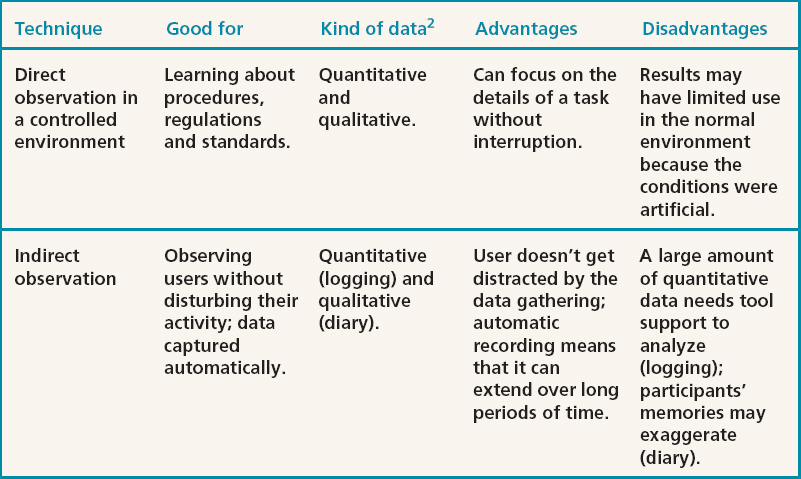

In Table 7.1 we summarize the key features, advantages, and drawbacks of these three combinations of data recording techniques.

Table 7.1 Comparison of the three main approaches to data recording

7.4 Interviews

Interviews can be thought of as a “conversation with a purpose” (Kahn and Cannell, 1957). How like an ordinary conversation the interview can be depends on the type of interview method used. There are four main types of interviews: open-ended or unstructured, structured, semi-structured, and group interviews (Fontana and Frey, 1994). The first three types are named according to how much control the interviewer imposes on the conversation by following a predetermined set of questions. The fourth involves a small group guided by a facilitator.

The most appropriate approach to interviewing depends on the purpose of the interview, the questions to be addressed, and the stage in the lifecycle. For example, if the goal is to gain first impressions about how users react to a new design idea, such as an interactive sign, then an informal, open-ended interview is often the best approach. But if the goal is to get feedback about a particular design feature, such as the layout of a new web browser, then a structured interview or questionnaire is often better. This is because the goals and questions are more specific in the latter case.

7.4.1 Unstructured Interviews

Open-ended or unstructured interviews are at one end of a spectrum of how much control the interviewer has over the interview process. They are exploratory and are more like conversations around a particular topic; they often go into considerable depth. Questions posed by the interviewer are open, meaning that there is no particular expectation about the format or content of answers. Open questions are used when you want to explore the range of opinions. For example, “What are the advantages of using a PDA?” Here, the interviewee is free to answer as fully or as briefly as she wishes and both interviewer and interviewee can steer the interview.

It is always advisable to have a plan of the main topics to be covered. Going into an interview without an agenda should not be confused with being open to new information and ideas (see Section 7.4.5 on planning an interview). One of the skills necessary for conducting an unstructured interview is getting the balance right between making sure that answers to relevant questions are obtained, while at the same time being prepared to follow new lines of enquiry that were not anticipated.

A benefit of unstructured interviews is that they generate rich data, i.e. data that gives a deep understanding of the topic, and is often interrelated and complex. In addition, interviewees may mention issues that the interviewer has not considered. But this benefit often comes at a cost. A lot of unstructured data is generated, which can be very time-consuming to analyze. It is also impossible to replicate the process, since each interview takes on its own format. Typically in interaction design, there is no attempt to analyze every interview in detail. Instead, the interviewer makes notes or audio records the session and then goes back through the data afterwards to note the main issues of interest.

7.4.2 Structured Interviews

In structured interviews, the interviewer asks predetermined questions similar to those in a questionnaire (see Section 7.5). Structured interviews are useful when the goals are clearly understood and specific questions can be identified. To work best, the questions need to be short and clearly worded. Typically the questions are closed, which means that they require an answer from a predetermined set of alternatives. Responses may involve selecting from a set of options that are read aloud or presented on paper. Closed questions work well for fast interviews when the range of answers is known, and where people tend to be in a rush. In a structured interview the same questions are used with each participant so the study is standardized. Example questions for a structured interview might be:

- Which of the following websites do you visit most frequently: amazon.com, barnes&noble.com, google.com, msn.com?

- How often do you visit this website: every day, once a week, once a month, less often than once a month?

- Have you ever purchased anything online?

- If so, how often do you purchase items online: every day, once a week, once a month, less often than once a month?

Questions in a structured interview should be worded exactly the same for each participant, and they should be asked in the same order.

7.4.3 Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews combine features of structured and unstructured interviews and use both closed and open questions. For consistency the interviewer has a basic script for guidance, so that the same topics are covered with each interviewee. The interviewer starts with preplanned questions and then probes the interviewee to say more until no new relevant information is forthcoming. For example:

Which music websites do you visit most frequently? <Answer mentions several but stresses that she prefers hottestmusic.com>

Why? <Answer says that she likes the site layout>

Tell me more about the site layout <Silence, followed by an answer describing the site's navigation>

Anything else that you like about the site? <Answer describes the animations>

Thanks. Are there any other reasons for visiting this site so often that you haven't mentioned?

It is important not to pre-empt an answer by phrasing a question to suggest that a particular answer is expected. For example, “You seemed to like this use of color …” assumes that this is the case and will probably encourage the interviewee to answer that this is true so as not to offend the interviewer. Children are particularly prone to behave in this way (see Box 7.2 for more on data gathering with children). The body language of the interviewer, for example, whether she is smiling, scowling, looking disapproving, etc., can have a strong influence on whether the interviewee will agree with a question.

Also, the interviewer needs to give the person time to speak and not move on too quickly. Probes are a device for getting more information, especially neutral probes such as, “Do you want to tell me anything else?” The person may also be prompted to help her along. For example, if the interviewee is talking about a computer interface but has forgotten the name of a key menu item, the interviewer might want to remind her so that the interview can proceed productively. Semi-structured interviews are intended to be broadly replicable, so probing and prompting should aim to help the interview along without introducing bias.

Box 7.2: Working with children

Children think and react to situations differently from adults. Sitting a 4-year-old child down in a formal interview situation is unlikely to result in anything other than a wall of silence. If children are to be included in your data gathering sessions, then child-friendly methods are needed to make them feel at ease. For example, for very young children of pre-reading or early reading age, data gathering sessions need to rely on images and chat rather than written instructions or questionnaires. Read et al. (2002) have developed a set of ‘smileys’ for use with children in interviews (see Figure 7.1). Recording children can also pose its problems. Children have a tendency to perform in front of a camera unless it is placed behind them, or they are given time to get used to it being there.

Figure 7.1 A smileyometer gauge for early readers

The appropriate techniques to involve children also depend on the goal of the data gathering session. For example, Guha et al. (2005) work with children as technology design partners. They focus on children between the ages of 7 and 11. They have found that unexpected innovations result when working as an inter-generational team, i.e. adults and children working together. The method they use is called cooperative inquiry (Druin, 2002) and is based on Scandinavian cooperative design practices, participatory design, and contextual inquiry. There are many techniques that can be used in cooperative inquiry, such as sketching ideas and brainstorming, and observational research which has been modified to accommodate children's preferred approaches. For example, the ‘mixing ideas’ approach (which also works with younger children, aged 5 to 6) involves three stages. In the first stage, each child generates ideas, working one-on-one with an adult. In the second stage, groups of adults and children mix together these ideas. Finally, all the ideas are mixed together to form ‘the big idea’ (see Figure 7.2). Guha et al. report that they are currently developing technology reflecting concepts that emerged from the big idea.

In contrast, the Equator project investigated the use of new technology to encourage children to record and analyse aspects of the environment themselves. For example, Rogers et al. (2005) report on the Ambient Wood project which investigates the use of ubiquitous computing and mobile technologies to support learning. In this work, a learning experience was designed that encourages children to explore habitats in a woodland area. Each child was given a PDA and a mobile probing tool (see Figure 7.3), which can collect data about their environment and send it to a central server. The data collected by the probe could be collated and displayed on the PDA in real time, thus giving immediate feedback to their investigations. The child's position was also monitored and location-specific data sent to their PDA, e.g. when they walked past a specific plant.

Figure 7.2 The cut up and remixed big idea

Figure 7.3 The probing tool in the Ambient Wood project being used to collect light and moisture readings

7.4.4 Focus Groups

Interviews are often conducted with one interviewer and one interviewee, but it is also common to interview people in groups. One form of group interview that is frequently used in marketing, political campaigning, and social sciences research is the focus group. Normally 3 to 10 people are involved, and the discussion is led by a trained facilitator. Participants are selected to provide a representative sample of the target population. For example, in an evaluation of a university website, a group of administrators, faculty, and students may form three separate focus groups because they use the web for different purposes. In requirements activities it is quite common to hold a focus group in order to identify conflicts in terminology or expectations from different sections within one department or organization.

The benefit of a focus group is that it allows diverse or sensitive issues to be raised that might otherwise be missed. The method assumes that individuals develop opinions within a social context by talking with others. Often questions posed to focus groups seem deceptively simple, but the idea is to enable people to put forward their own opinions in a supportive environment. A preset agenda is developed to guide the discussion, but there is sufficient flexibility for the facilitator to follow unanticipated issues as they are raised. The facilitator guides and prompts discussion and skillfully encourages quiet people to participate and stops verbose ones from dominating the discussion. The discussion is usually recorded for later analysis and participants may be invited to explain their comments more fully.

Focus groups can be very relaxed affairs (for the participants that is), but in some product development methods, focus groups have become very formalized. For example, the workshops (as they are called) used in Joint Application Development (Wood and Silver, 1995) are very structured, and their contents and participants are all prescribed.

Dilemma What they say and what they do

What users say isn't always what they do. When asked a question, people sometimes give the answers that they think show them in the best light, or they may just forget what happened or how long they spent on a particular activity. For example, in a study looking at the maintenance of telecommunications software, the developers stated that most of their job involved reading documentation, but when observed, it was found that searching and looking at source code was much more common than looking at documentation (Singer et al., 1997).

So, can interviewers believe all the responses they get? Are the respondents giving ‘the truth’ or are they simply giving the answers that they think the interviewer wants to hear?

It isn't possible to avoid this behavior, but it is important to be aware of it and to reduce such biases by choosing questions carefully, getting a large number of participants or by using a combination of data gathering techniques.

7.4.5 Planning and Conducting an Interview

Planning an interview involves developing the set of questions or topics to be covered, collating any documentation to give to the interviewee (such as consent form or project description), checking that recording equipment works in advance and you know how to use it, working out the structure of the interview, and organizing a suitable time and place.

Developing Interview Questions

Questions for an interview may be open or closed. Open questions are best suited to interviews where the goal of the session is exploratory. Closed questions require a list of possible answers, and so they can only be used in a situation where you know the possible answers in advance. It is always possible to have an ‘other’ option, but the ideal is that this option is not used very often. So whether you choose to use open questions or closed questions depends on what is already known about the topic of investigation and the goal of the interview. An unstructured interview will usually consist entirely of open questions, while a structured interview will usually consist of closed questions. A semi-structured interview may use a combination of both types.

The following guidelines for developing interview questions are derived from Robson (2002):

- Compound sentences can be confusing, so split them into two separate questions. For example, instead of, “How do you like this cell phone compared with previous ones that you have owned?” Say, “How do you like this cell phone?” “Have you owned other cell phones?” If so, “How did you like it?” This is easier for the interviewee to respond to and easier for the interviewer to record.

- Interviewees may not understand jargon or complex language and might be too embarrassed to admit it, so explain them in layman's terms.

- Try to keep questions neutral, for example, if you ask “Why do you like this style of interaction?” this question assumes that the person does like it and will discourage some interviewees from stating their real feelings.

Activity 7.2

Cybelle (see Figure 7.4) is an intelligent agent that guides visitors to the website Agentland which contains information about intelligent agents. As Cybelle is an intelligent agent, it is not straightforward to interact with her, and she can be frustrating. However, she remembers your name between visits, which is friendly.

Figure 7.4 Cybelle the intelligent agent

Cybelle has a variety of facial expressions and although the answers to my questions were often strange, she has an interesting approach to life, and one might almost say that she has personality! To see Cybelle in action, go to the website (http://www.agentland.com/) and ask her some questions. You can ask any question you like, about intelligent agents, herself, or anything else. Alternatively, you can do this activity by just looking at the figure and thinking about the questions.

The developers of Cybelle want to find out whether this approach encourages interest in intelligent agents, or whether it turns people away. To this end, they have asked you to conduct some interviews for them.

- What is the goal of your data gathering session?

- Suggest ways of recording the interview data.

- Suggest a set of questions that are suitable for use in an unstructured interview that seek opinions about whether Cybelle would encourage or discourage interest in intelligent agents.

- Based on the results of the unstructured interviews, the developers of Cybelle have found that two important acceptance factors are whether she is amusing and whether she answers questions on intelligent agents accurately. Write a set of semi-structured interview questions to evaluate these two aspects. Show two of your peers the Cybelle website. Then ask them to comment on your questions. Refine the questions based on their comments.

- The goal is to seek opinions about whether Cybelle would encourage or discourage interest in intelligent agents.

- Taking notes might be cumbersome and distracting to the interviewee, and it would be easy to miss important points. An alternative is to audio record the session. Video recording is not needed as it isn't necessary to see the interviewee. However, it would be useful to have a camera at hand to take shots of the interface in case the interviewee wanted to refer to aspects of Cybelle.

- Possible questions include: Do you find chatting with Cybelle helpful? Does Cybelle answer your questions on intelligent agents appropriately? In what way(s) does Cybelle affect your interest in intelligent agents?

- Semi-structured interview questions may be open or closed. Some closed questions that you might ask include:

- Have you seen Cybelle before?

- Would you like to find out about intelligent agents from Cybelle?

- In your opinion, is Cybelle amusing or irritating?

Some open questions, with follow-on probes, include:

- What do you like most about Cybelle? Why?

- What do you like least about Cybelle? Why?

- Please give me an example where Cybelle amused or irritated you.

It is helpful when collecting answers to list the possible responses together with boxes that can just be checked (i.e. ticked). Here's how we could convert some of the questions from Activity 7.2.

- Have you seen Cybelle before? (Explore previous knowledge)

- Would you like to find out about intelligent agents from Cybelle? (Explore initial reaction, then explore the response)

- Why?

If response is “Yes” or “No,” interviewer says, “Which of the following statements represents your feelings best?”

For “Yes,” Interviewer checks the box

□ I don't like typing

□ This is fun/cool

□ It's going to be the way of the future

□ Another reason (Interviewer notes the reason)

For “No,” Interviewer checks the box

□ I don't like systems that pretend to be people

□ She doesn't answer my questions clearly

□ I don't like her ‘personality’

□ Another reason (Interviewer notes the reason)

- In your opinion, is Cybelle amusing or irritating?

Interviewer checks box

□ Amusing

□ Irritating

□ Neither

Running the interview

Before starting, make sure that the aims of the interview have been communicated to and understood by the interviewees, and they feel comfortable. Some simple techniques can help here, such as finding out about their world before the interview so that you can dress, act, and speak in a manner that will be familiar. This is particularly important when working with disadvantaged groups such as disabled people, children, or seriously ill patients.

During the interview, it is better to listen more than to talk, to respond with sympathy but without bias, and even to enjoy the interview (Robson, 2002). Robson suggests the following steps for an interview:

- An introduction in which the interviewer introduces himself and explains why he is doing the interview, reassures interviewees regarding any ethical issues, and asks if they mind being recorded, if appropriate. This should be exactly the same for each interviewee.

- A warm-up session where easy, non-threatening questions come first. These may include questions about demographic information, such as “What area of the country do you live in?”

- A main session in which the questions are presented in a logical sequence, with the more probing ones at the end. In a semi-structured interview the order of questions may vary between participants, depending on the course of the conversation and what seems more natural.

- A cool-off period consisting of a few easy questions (to defuse tension if it has arisen).

- A closing session in which the interviewer thanks the interviewee and switches off the recorder or puts her notebook away, signaling that the interview has ended.

7.4.6 Other Forms of Interview

Telephone interviews are a good way of interviewing people with whom you cannot meet. You cannot see their body language, but apart from this telephone interviews have much in common with face-to-face interviews.

Online interviews, using either asynchronous communication such as email or synchronous communication such as instant messaging, can also be used. For interviews that involve sensitive issues, answering questions anonymously may be preferable to meeting face-to-face. If, however, face-to-face meetings are desirable but impossible because of geographical distance, video-conferencing systems can be used. Feedback about a product or a process can also be obtained from customer help lines, consumer groups, and online customer communities that provide help and support, e.g. see Box 9.2 on user involvement at Microsoft.

At various stages of design, it is useful to get quick feedback from a few users through short interviews, which are often more like conversations, in which users are asked their opinions.

Retrospective interviews, i.e. interviews which reflect on an activity that was performed in the recent past, are often conducted to check with participants that the interviewer has correctly understood what was happening.

7.4.7 Enriching The Interview Experience

Interviews often take place in a neutral environment, e.g. a meeting room away from the interviewee's normal desk, and the interview situation provides an artificial context, i.e. separate from normal tasks. In these circumstances it can be difficult for interviewees to give full answers to the questions posed. To help combat this, interviews can be enriched by using props such as prototypes or work artifacts that the interviewee or interviewer brings along, or descriptions of common tasks (examples of these kinds of props are scenarios and prototypes, which are covered in Chapters 10 and 11). These props can be used to provide context for the interviewees and help to ground the data in a real setting. Figure 7.5 illustrates the use of prototypes in a focus group setting.

For example, Jones et al. (2004) used diaries as a basis for interviews. They performed a study to probe the extent to which certain places are associated with particular activities and information needs. Each participant was asked to keep a diary in which they entered information about where they were and what they were doing at 30 minute intervals. The interview questions were then based around their diary entries.

7.5 Questionnaires

Questionnaires are a well-established technique for collecting demographic data and users' opinions. They are similar to interviews in that they can have closed or open questions. Effort and skill are needed to ensure that questions are clearly worded and the data collected can be analyzed efficiently. Clearly worded questions are particularly important when there is no researcher present to encourage the respondent and to resolve any ambiguities or misunderstandings. Well-designed questionnaires are good at getting answers to specific questions from a large group of people, and especially if that group of people is spread across a wide geographical area, making it infeasible to visit them all. Questionnaires can be used on their own or in conjunction with other methods to clarify or deepen understanding. For example, information obtained through interviews with a small selection of interviewees might be corroborated by sending a questionnaire to a wider group to confirm the conclusions. The methods and questions used depend on the context, target audience, data gathering goal, and so on.

Figure 7.5 Enriching a focus group with prototypes. Here prototype screens are displayed on the wall for all participants to see

The questions asked in a questionnaire, and those used in a structured interview, are similar, so how do you know when to use which technique? Essentially, the difference lies in the motivation of the respondent to answer the questions. If you think that this motivation is high enough to complete a questionnaire without anyone else present, then a questionnaire will be cheaper and easier to organize. On the other hand, if the respondents need some persuasion to answer the questions, it would be better to use an interview format and ask the questions face-to-face through a structured interview. For example, structured interviews are easier and quicker to conduct in situations in which people will not stop to complete a questionnaire, such as at a train station or while walking to their next meeting. One approach which lies between these two is the telephone interview.

It can be harder to develop good questionnaire questions compared with structured interview questions because the interviewer is not available to explain them or to clarify any ambiguities. Because of this, it is important that questions are specific; when possible, closed questions should be asked and a range of answers offered, including a ‘no opinion’ or ‘none of these’ option. Finally, negative questions can be confusing and may lead to the respondents giving false information. Some questionnaire designers use a mixture of negative and positive questions deliberately because it helps to check the users' intentions. In contrast, the designers of QUIS (Box 7.3) (Chin et al., 1988) decided not to mix negative and positive statements because the questionnaire was already complex enough without forcing participants to pay attention to the direction of the argument.

Box 7.3: QUIS, Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction

The Questionnaire for User Interaction Satisfaction (QUIS), developed by the University of Maryland Human–Computer Interaction Laboratory, is one of the most widely used questionnaires for evaluating interfaces (Chin et al., 1988; Shneiderman, 1998a). Although developed for evaluating user satisfaction, it is frequently applied to other aspects of interaction design. An advantage of this questionnaire is that it has gone through many cycles of refinement and has been used for hundreds of evaluation studies, so it is well tried and tested. The questionnaire consists of the following 12 parts that can be used in total or in parts:

- system experience (i.e. time spent on this system)

- past experience (i.e. experience with other systems)

- overall user reactions

- screen design

- terminology and system information

- learning (i.e. to operate the system)

- system capabilities (i.e. the time it takes to perform operations)

- technical manuals and online help

- online tutorials

- multimedia

- teleconferencing

- software installation.

Notice that the third part of QUIS assesses users' overall reactions. Evaluators often use this part on its own because it is short so people are likely to respond.

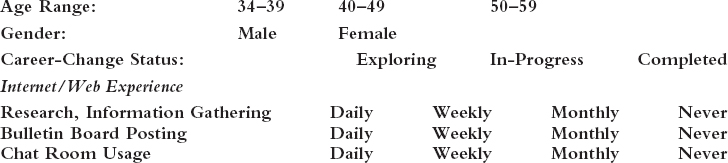

7.5.1 Designing The Questionnaire's Structure

Many questionnaires start by asking for basic demographic information, e.g. gender, age, place of birth, and details of relevant experience, e.g. the time or number of years spent using computers, or the level of expertise within the domain under study, etc. This background information is useful for putting the questionnaire responses into context. For example, if two respondents conflict, these different perspectives may be due to their level of experience—a group of people who are using the web for the first time are likely to express different opinions regarding websites to another group with five years of web experience. However, only contextual information that is relevant to the study goal needs to be collected. In the website example above, it is unlikely that the person's shoe size will provide relevant context to their responses!

Specific questions that contribute to the data gathering goal usually follow these more general questions. If the questionnaire is long, the questions may be subdivided into related topics to make it easier and more logical to complete.

The following is a checklist of general advice for designing a questionnaire:

- Think about the ordering of questions. The impact of a question can be influenced by question order.

- Consider whether you need different versions of the questionnaire for different populations.

- Provide clear instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. For example, if you want a check put in one of the boxes, then say so. Questionnaires can make their message clear with careful wording and good typography.

- A balance must be struck between using white space and the need to keep the questionnaire as compact as possible. Long questionnaires cost more and deter participation and completion.

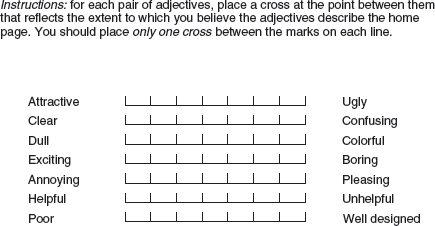

Box 7.4 contains an excerpt from a paper questionnaire designed to evaluate users' satisfaction with some specific features of a prototype website for career changers aged 34–59 years.

Box 7.4: An Excerpt from a User Satisfaction Questionnaire Used to Evaluate a Website for Career Changers

Notice that in the following excerpt most questions involve circling the appropriate response, or checking the box that most closely describes their opinion: these are commonly used techniques. Fewer than 50 participants were involved in this study, so inviting them to write an open-ended comment suggesting recommendations for change was manageable. It would have been difficult to collect this information with closed questions, since good suggestions would undoubtedly have been missed because the evaluator is unlikely to have thought to ask about them.

Please circle the most appropriate selection:

Please rate (i.e. check the box to show) agreement or disagreement with the following statements:

Please add any recommendations for changes to the overall design, language or navigation of the website on the back of this paper.

Thanks for your participation in the testing of this prototype.

From Andrews et al., (2001).

7.5.2 Question and Response Format

There are several different types of question, each of which requires a particular kind of response. For example, closed questions require an answer from a set of possibilities while open questions are unrestricted. Sometimes many options can be chosen, sometimes respondents need to indicate only one, and sometimes it is better to ask users to locate their answer within a range. Selecting the most appropriate question and response format makes it easier for respondents to be able to answer clearly. Some commonly used formats are described below.

Check boxes and ranges

The range of answers to demographic questionnaires is predictable. Gender, for example, has two options, male or female, so providing the two options and asking respondents to circle a response makes sense for collecting this information (as in Box 7.4). A similar approach can be adopted if details of age are needed. But since some people do not like to give their exact age, many questionnaires ask respondents to specify their age as a range (see Box 7.4). A common design error arises when the ranges overlap. For example, specifying two ranges as 15–20, 20–25 will cause confusion: which box do people who are 20 years old check? Making the ranges 14–19, 20–24 avoids this problem.

A frequently asked question about ranges is whether the interval must be equal in all cases. The answer is that it depends on what you want to know. For example, if you want to collect information for the design of an e-commerce site to sell life insurance, the target population is going to be mostly people with jobs in the age range of, say, 21–65 years. You could, therefore, have just three ranges: under 21, 21–65, and over 65. In contrast, if you wanted to see how the population's political views varied across the generations, you might be interested in looking at 10-year cohort groups for people over 21, in which case the following ranges would be appropriate: under 21, 22–31, 32–41, etc.

Rating scales

There are a number of different types of rating scales that can be used, each with its own purpose (see Oppenheim, 1992). Here we describe two commonly used scales, Likert and semantic differential scales. The purpose of these is to elicit a range of responses to a question that can be compared across respondents. They are good for getting people to make judgments about things, e.g. how easy, how usable, etc., and therefore are important for usability studies.

Likert scales rely on identifying a set of statements representing a range of possible opinions, while semantic differential scales rely on choosing pairs of words that represent the range of possible opinions. Likert scales are more commonly used because identifying suitable statements that respondents will understand is easier than identifying semantic pairs that respondents interpret as intended.

Likert scales. Likert scales are used for measuring opinions, attitudes, and beliefs, and consequently they are widely used for evaluating user satisfaction with products. For example, users' opinions about the use of color in a website could be evaluated with a Likert scale using a range of numbers, as in (1), or with words as in (2):

- The use of color is excellent (where 1 represents strongly agree and 5 represents strongly disagree):

- The use of color is excellent:

In both cases, respondents could be given a box to tick as shown, or they could be asked to ring the appropriate number or phrase, in which case the boxes are not needed. Designing a Likert scale involves the following three steps:

- Gather a pool of short statements about the subject to be investigated. For example, “This control panel is easy to use” or “The procedure for checking credit rating is too complex.” A brainstorming session with peers in which you identify key aspects to be investigated is a good way of doing this.

- Decide on the scale. There are three main issues to be addressed here: how many points does the scale need? Should the scale be discrete or continuous? How to represent the scale? See Box 7.5 for more on this topic.

- Select items for the final questionnaire and reword as necessary to make them clear.

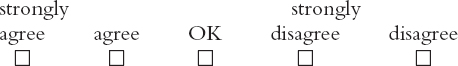

Semantic differential scales. Semantic differential scales are used less frequently than Likert scales, possibly because it is harder to find pairs of words that can be interpreted consistently by participants. They explore a range of bipolar attitudes about a particular item. Each pair of attitudes is represented as a pair of adjectives. The participant is asked to place a cross in one of a number of positions between the two extremes to indicate agreement with the poles, as shown in Figure 7.6. The score for the evaluation is found by summing the scores for each bipolar pair. Scores can then be computed across groups of participants. Notice that in this example the poles are mixed so that good and bad features are distributed on the right and the left. In this example there are seven positions on the scale.

Figure 7.6 An example of a semantic differential scale

Box 7.5: What Scales to Use—3, 5, 7, or More?

When designing Likert and semantic differential scales, issues that need to be addressed include: how many points are needed on the scale? How should they be presented, and in what form?

Many questionnaires use seven- or five-point scales and there are also three-point scales. Arguments for the number of points go both ways. Advocates of long scales argue that they help to show discrimination, as advocated by the QUIS team (QUIS has a nine-point scale; Box 7.3 (Chin et al., 1988)). Rating features on an interface is more difficult for most people than, say, selecting among different flavors of ice cream, and when the task is difficult there is evidence to show that people ‘hedge their bets.’ Rather than selecting the poles of the scales if there is no right or wrong, respondents tend to select values nearer the center. The counter-argument is that people cannot be expected to discern accurately among points on a large scale, so any scale of more than five points is unnecessarily difficult to use.

Another aspect to consider is whether the scale should have an even or odd number of points. An odd number provides a clear central point. On the other hand, an even number forces participants to make a decision and prevents them from sitting on the fence.

We suggest the following guidelines:

How many points on the scale?

Use a small number, e.g. 3, when the possibilities are very limited, as in yes/no type answers:

![]()

Use a medium-sized range, e.g. 5, when making judgments that involve like/dislike, agree/disagree statements:

Use a longer range, e.g. 7 or 9, when asking respondents to make subtle judgments. For example, when asking about a user experience dimension such as ‘level of appeal’ of a character in a video game:

![]()

Discrete or continuous?

Use boxes for discrete choices and scales for finer judgments.

What order?

Place the positive end of the scale first and the negative end last. This matches the logical way people think about scoring. For example:

- — strongly agree

- — slightly agree

- — agree

- — slightly disagree

- — strongly disagree.

Activity 7.3

Spot four poorly designed features in Figure 7.7.

Comment

Some of the features that could be improved include:

- Question 2 requests exact age. Many people prefer not to give this information and would rather position themselves in a range.

- In question 3, years of experience is indicated with overlapping scales, i.e. 1, <1–3, 3–5, etc. How do you answer if you have 1, 3, or 5 years of experience?

- For question 4, the questionnaire doesn't tell you whether you should check one, two, or as many boxes as you wish.

- The space left for people to answer the open-ended question 5 is too small, which will annoy some people and deter them from giving their opinions.

7.5.3 Administering questionnaires

Two important issues when using questionnaires are reaching a representative sample of participants and ensuring a reasonable response rate. For large surveys, potential respondents need to be selected using a sampling technique. However, interaction designers commonly use small numbers of participants, often fewer than 20 users. 100% completion rates are often achieved with these small samples, but with larger or more remote populations, ensuring that surveys are returned is a well-known problem. 40% return is generally acceptable for many surveys, but much lower rates are common. Depending on your audience you might want to consider offering incentives (see Section 7.2.2).

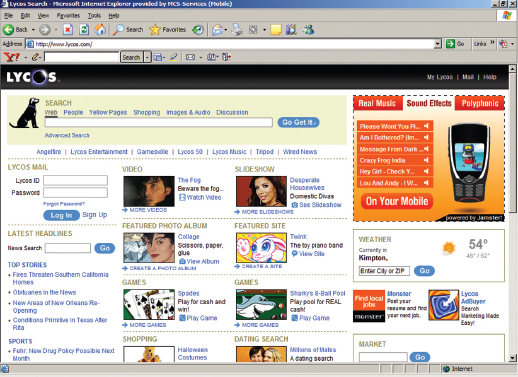

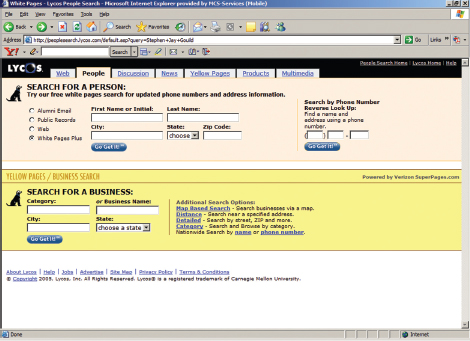

7.5.4 Online questionnaires

Online questionnaires are becoming increasingly common because they are effective for reaching large numbers of people quickly and easily. There are two types: email and web-based. The main advantage of email is that you can target specific users. But unless email is just used to contact potential respondents and point them to a web-based questionnaire, an email questionnaire is likely to be simply an electronic editable version of a paper-based questionnaire, and this loses some of the advantages you get with a web-based questionnaire. For example, a web-based questionnaire can be interactive and can include check boxes, pull-down and pop-up menus, help screens, and graphics, e.g. Figure 7.8. It can also provide immediate data validation and can enforce rules such as select only one response, or certain types of answers such as numerical, which cannot be done in email or with paper. Other advantages of web-based questionnaires include faster response rates and automatic transfer of responses into a database for analysis (Andrews et al., 2003).

The main problem with web-based questionnaires is obtaining a random sample of respondents. As there is no central registry of Internet users, it is not possible to identify the size and demography of the full population being surveyed, and traditional sampling methods cannot be used. This means that the respondents are inevitably self-selecting and so the results cannot be generalized to offline populations. This was a criticism of the survey run by Georgia Tech's GVU (Graphic, Visualization and Usability) Centre, one of the first online surveys. This survey collected demographic and activity information from Internet users twice yearly between January 1994 and October 1998. The policy that GVU employed to deal with this difficult sampling issue was to make as many people aware of the GVU survey as possible so that a wide variety of participants were encouraged to respond. However, even these efforts did not avoid biased sampling, since participants were still self-selecting.

Figure 7.8 An excerpt from a web-based questionnaire showing pull-down menus

Some survey experts instead propose using national census records to sample offline (Nie and Ebring, 2000). The highly regarded PEW surveys select households to poll using random digit samples of telephone numbers, but these are telephone surveys and an equivalently reliable sampling method has not yet been suggested for online surveys. In some countries, web- and mobile phone-based questions are used in conjunction with television to elicit viewers' opinions of programs and political events, e.g. the television program Big Brother. A term that is gaining popularity is convenience sampling, which is another way of saying that the sample includes those who were available rather than those selected using scientific sampling.

Designing a web-based questionnaire involves the following steps (Andrews et al., 2003):

- Devise the questionnaire as if it is to be delivered on paper first, following the general guidelines introduced above.

- Develop strategies for reaching the target population.

- Produce an error-free interactive electronic version from the original paper-based one. It may also be useful to embed feedback and pop-up help within the questionnaire.

- Make the questionnaire accessible from all common browsers and readable from different-sized monitors and different network locations.

- Make sure information identifying each respondent can be captured and stored confidentially because the same person may submit several completed surveys. This can be done by recording the Internet domain name or the IP address of the respondent, which can then be transferred directly to a database. However, this action could infringe people's privacy and the legal situation should be checked. Another way is to access the transfer and referrer logs from the web server, which provide information about the domains from which the web-based questionnaire was accessed. Unfortunately, people can still send from different accounts with different IP addresses, so additional identifying information may also be needed.

- Thoroughly pilot test the questionnaire. This may be achieved in four stages: the survey is reviewed by knowledgeable analysts; typical participants complete the survey using a think-aloud protocol (see below); a small version of the study is attempted; a final check to catch small errors is conducted.

There are many online questionnaire templates available on the web that provide a range of choices, including different question types (e.g. open, multiple choice), rating scales (e.g. Likert, semantic differential), and answer types (e.g. radio buttons, check boxes, drop-down menus). The following activity asks you to make use of one of these templates to design a questionnaire for the web.

Activity 7.4

Go to questionpro.com, or a similar survey site, that allows you to design your own questionnaire using their set of widgets for a free trial period (http://www.questionpro.com/buildyoursurvey/ at time of writing).

Create a web-based questionnaire for the set of questions you developed for Activity 7.2 (Cybelle). For each question produce two different designs, for example radio buttons and drop-down menus for one question; for another question provide a 10-point semantic differential scale and a 5-point scale.

What differences (if any) do you think your two designs will have on a respondent's behavior? Ask a number of people to answer one or other of your questions and see if the answers differ for the two designs.

Comment

You may have found that respondents use the response types in different ways. For example, they may select the end options more often from a drop-down menu than from a list of options that are chosen via radio buttons. Alternatively, you may find no difference and that people's opinions are not affected by the widget style used at the interface. Any differences found, of course, may be due to the variation between individual responses rather than being caused by features in the questionnaire design. To tease the effects apart you would need to ask a large number of participants, e.g. in the order of 50–100, to respond to the questions for each design.

Box 7.6: Do People Answer Online Questionnaires Differently to Paper and Pencil? If so, why?

There has been much research examining how people respond to surveys when using a computer compared with the traditional paper and pencil method. Some studies suggest that people are more revealing and consistent in their responses when using a computer to report their habits and behaviors, such as eating, drinking, and amount of exercise, e.g. Luce et al. (2003). Students have also been found to rate their instructors less favorably when online, suggesting they are more honest in their views of their instructors (Chang, 2004). One reason for this is that students may feel less social pressure when filling in a questionnaire at a computer and hence freer to write the truth than when sitting in a classroom, with others around them, filling out a paper-based version.

Another factor that can influence how people answer questions is the way the information is structured on the screen or page, such as the use of headers, the ordering, and the placement of questions. But the potential may be greater for web-based questionnaires since they provide more opportunities than paper ones for manipulating information (Smyth et al., 2004). For example, the use of dropdown menus, radio buttons, and jump-to options may influence how people read and navigate a questionnaire. Research is beginning to investigate how such interactivity affects respondents' behavior when thinking about their replies; for example, Smyth et al. (2005) have found that providing forced choice formats results in more options being selected. The initial findings suggest that instead of prescribing a generic design format for all web-based questionnaires, e.g. using only radio buttons or entry check boxes, that the design should be selected based on the purpose of the questionnaire and the types of questions being asked (Gunn, 2002).

7.6 Observation

Observation is a useful data gathering technique at any stage during product development. Early in design, observation helps designers understand the users' context, tasks, and goals. Observation conducted later in development, e.g. in evaluation, may be used to investigate how well the developing prototype supports these tasks and goals.

Users may be observed directly by the investigator as they perform their activities, or indirectly through records of the activity that are read afterwards. Observation may also take place in the field, or in a controlled environment. In the former case, individuals are observed as they go about their day-to-day tasks in the natural setting. In the latter case, individuals are observed performing specified tasks within a controlled environment such as a usability laboratory.

Activity 7.5

To appreciate the different merits of observation in the field and observation in a controlled environment, read the scenarios below and answer the questions that follow.

Scenario 1. A usability consultant joins a group who have been given GPS-based phones to test on a visit to Stockholm. Not knowing the restaurants in the area, they use the GPS-based phone to find a list of restaurants within a five-mile radius of their hotel. Several are listed and while the group waits for a taxi, they find the telephone numbers of a couple, call them to ask about their menus, select one, make a booking, and head off to the restaurant. The usability consultant observes some problems keying instructions because the buttons seem small. She also notices that the text on the screen seems rather small, but the person using it is able to get the information needed and call the restaurant. Discussion with the group supports the evaluator's impression that there are problems with the interface, but on balance the device is useful and the group is pleased to get a table at a good restaurant nearby.

Scenario 2. A usability consultant observes how participants perform a preplanned task using the GPS-based phone in a usability laboratory. The task requires the participants to find the telephone number of a restaurant called Matisse. It takes them several minutes to do this and they appear to have problems. The video recording and interaction log suggest that the screen is too small for the amount of information they need to access and this is supported by participants' answers on a user satisfaction questionnaire.

- In which situation does the observer take the most control?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of these two types of observation?

- When might each type of observation be useful?

Comment

- The observer takes most control in the second study. The task is predetermined, the participant is instructed what to do, and she is located in a controlled laboratory environment.

- The advantages of the field study are that the observer saw how the device could be used in a real situation to solve a real problem. She experienced the delight expressed with the overall concept and the frustration with the interface. By watching how the group used the device ‘on the move,’ she gained an understanding of what they liked and what was lacking. The disadvantage is that the observer was an insider in the group, so how objective could she be? The data is qualitative and while anecdotes can be very persuasive, how useful are they? Maybe she was having such a good time that her judgment was clouded and she missed hearing negative comments and didn't notice some people's annoyance. Another study could be done to find out more, but it is not possible to replicate the exact situation, whereas the laboratory study is easier to replicate. The advantages of the laboratory are that several users performed the same task, so different users' performance could be compared and averages calculated. The observer could also be more objective because she was more of an outsider. The disadvantage is that the study is artificial and says nothing about how the device would be used in the real environment.

- Both types of study have merits. Which is better depends on the goals of the study. The laboratory study is useful for examining details of the interaction style to make sure that usability problems with the interface and button design are diagnosed and corrected. The field study reveals how the phone is used in a real-world context and how it integrates with or changes users' behavior. Without this study, it is possible that developers might not have discovered the enthusiasm for the phone because the reward for doing laboratory tasks is not as compelling as a good meal!

7.6.1 Direct Observation in The Field

It can be very difficult for people to explain what they do or to even describe accurately how they achieve a task. So it is very unlikely that an interaction designer will get a full and true story by using interviews or questionnaires. Observation in the field can help fill in details and nuances that are not elicited from the other forms of investigation. It also provides context for tasks, and contextualizing the users and the interactive product provides important information about why activities happen the way they do. However, observation in the field can be complicated and can result in a lot of data that is not very relevant if it is not planned and carried out carefully.

Activity 7.6

- Find a small group of people who are using any kind of technology, e.g. computers, household, or entertainment appliances, and try to answer the question, “What are these people doing?” Watch for three to five minutes and write down what you observe. When you have finished, note down how you felt doing this, and any reactions in the group of people you observed.

- If you were to observe the group again, how would you change what you did the first time?

Comment

- The chances are that you found the experience prompted many uncertainties. For example, were the group talking, working, playing, or something else? How were you able to decide? Did you feel awkward or embarrassed watching? Did you wonder whether you should tell them that you were observing them? What problems did you encounter doing this exercise? Was it hard to watch everything and remember what happened? What were the most important things? Did you wonder if you should be trying to identify and remember just those things? Was remembering the order of events tricky? Perhaps you naturally picked up a pen and paper and took notes. If so, was it difficult to record fast enough? How do you think the people being watched felt? Did they know they were being watched? Did knowing affect the way they behaved? Perhaps some of them objected and walked away. If you didn't tell them, do you think you should have?

- The initial goal of the observation, i.e. to find out what the people are doing, was vague, and the chances are that it was quite a frustrating experience not knowing what was significant for answering your question and what could be ignored. The questions used to guide observation need to be more focused. For example, you might ask, what are the people doing with the technology? Is everyone in the group using it? Are they looking pleased, frustrated, serious, happy? Does the technology appear to be central to the users' goals?

All data gathering should have a clearly stated goal, but it is particularly important to have a focus for an observation session because there is always so much going on. On the other hand, it is also important to be able to respond to changing circumstances; for example, you may have planned one day to observe a particular person performing a task, but you are invited to an unexpected meeting which is relevant to your observation goal, and so it makes sense to attend the meeting instead. In observation there is a careful balance between being guided by goals and being open to modifying, shaping, or refocusing the study as you learn about the situation. Being able to keep this balance is a skill that develops with experience.

Dilemma: When should I stop observing?

Knowing when to stop doing any type of data gathering can be difficult for novices, but it is particularly tricky in observational studies because there is no obvious ending. Schedules often dictate when your study ends. Otherwise, stop when you stop learning new things. Two indications of having done enough are when you start to see similar patterns of behavior being repeated, or when you have listened to all the main stakeholder groups and understand their perspectives.

Structuring frameworks for observation in the field

During an observation, events can be complex and rapidly changing. There is a lot for observers to think about, so many experts have a framework to structure and focus their observation. The framework can be quite simple. For example, this is a practitioner's framework for use in evaluation studies that focuses on just three easy-to-remember items to look for:

- The person. Who is using the technology at any particular time?

- The place. Where are they using it?

- The thing. What are they doing with it?

Even a simple framework such as this one based on who, where, and what can be surprisingly effective to help observers keep their goals and questions in sight. Experienced observers may, however, prefer more detailed frameworks, such as the one suggested by Colin Robson (2002) which encourages observers to pay greater attention to the context of the activity:

- Space. What is the physical space like and how is it laid out?

- Actors. What are the names and relevant details of the people involved?

- Activities. What are the actors doing and why?

- Objects. What physical objects are present, such as furniture?

- Acts. What are specific individual actions?

- Events. Is what you observe part of a special event?

- Time. What is the sequence of events?

- Goals. What are the actors trying to accomplish?

- Feelings. What is the mood of the group and of individuals?

Activity 7.7

As in Activity 7.6 above, find a small group of people who are using any kind of technology. Observe this group for about 10 minutes and write down your observations, structured using Robson's framework.

Then consider how you feel about this observation exercise compared to the previous one.

Comment

Hopefully you will have felt more confident this second time, partly because it is the second time you've done some observation, and partly because the framework provided you with a structure for what to look at.

Both of the frameworks introduced above are relatively general and could be used in many different types of study, but there are other frameworks that have been developed to focus on particular circumstances. For example, Rogers and Bellotti (1997) suggest a more specific framework to support field studies in conjunction with designing future technologies. They divide their set of questions into two parts: problematizing existing settings and envisioning future settings.

Problematizing existing settings

- Why is an observation about a work practice or other activity striking?

- What are the pros and cons of the existing ways technologies are used in a setting?

- How have ‘workarounds’ evolved and how effective are they?

- Why do certain old-fashioned practices, using seemingly antiquated technologies persist, despite more advanced technologies being available in the setting?

Envisioning future settings

- What would be gained and lost through changing current ways of working or carrying out an activity by introducing new kinds of technological support?

- What might be the knock-on effects for other practices and activities through introducing new technologies?

- How might other settings be enhanced and disrupted through deploying the same kinds of future technologies?

Degree of participation

Depending on the type of study, the degree of participation within the study environment varies across a spectrum, which can be characterized as ‘insider’ at one end and ‘outsider’ at the other (see Figure 7.9). Where a particular study falls along this spectrum depends on its goal and on the practical and ethical issues that constrain and shape it.

An observer who adopts an approach right at the ‘outsider’ end of the spectrum is called a ‘passive observer’ and she will not take any part in the study environment at all. It is difficult to be a truly passive observer if you are in the field, simply because you can't avoid interacting with the activities happening around you.

An observer who adopts an approach at the ‘insider’ end of this spectrum is called a ‘participant observer.’ This means that he attempts to become a full member of the group he is studying. This can also be a difficult role to play since being an observer requires a certain level of detachment, while being a full participant assumes a different role. As a participant observer it is important to keep the two roles clear and separate, so that observation notes are objective, while participation is also maintained. It may also not be possible to take a full participant observer approach, for other reasons. For example, you may not be skilled enough in the task at hand, the organization/group may not be prepared for you to take part in their activities, or the timescale may not provide sufficient opportunity to become familiar enough with the task to participate fully.

An interesting example of participant observation is provided by Nancy Baym's work (1997) in which she joined an online community interested in soap operas for over a year in order to understand how the community functioned. She told the community what she was doing and offered to share her findings with them. This honest approach gained her their trust, and they offered support and helpful comments. As Baym participated she learned about the community, who the key characters were, how people interacted, their values, and the types of discussion that were generated. She kept all the messages as data to be referred to later. She also adapted interviewing and questionnaire techniques to collect additional information. She summarizes her data gathering as follows:

Figure 7.9 The degree of participation varies along a spectrum from insider to outsider

The data for this study were obtained from three sources. In October 1991, I saved all the messages that appeared … I collected more messages in 1993. Eighteen participants responded to a questionnaire I posted … Personal email correspondence with 10 other … participants provided further information. I posted two notices to the group explaining the project and offering to exclude posts by those who preferred not to be involved. No one declined to participate. (Baym, 1997, p. 104)