4

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF MANUFACTURING COSTS: DIRECT MATERIAL AND DIRECT LABOR

GENERAL ASPECTS OF MANUFACTURING

Responsibilities of the Manufacturing Executive

To those not familiar with the intricacies of the modern manufacturing processes, it might seem that once a determination has been made of the products to be manufactured and sold, and of the quantities required, then the remaining task is simple: proceed to manufacture the articles. As compared with the task of the sales executive, many of the variables in manufacturing are more subject to the control of the executive than they are in selling, many are more easily measured, and the psychological factors may be less pronounced. But the job is by no means an easy one, and many difficulties plague the manufacturing manager who is attempting to deliver a quality product, within cost, and on schedule.

Consider some of the numerous decisions the manufacturing executive is called upon to make—in many of which the controller is not involved at all, others with which he may be only tangentially concerned, and yet others where he may be, or should be, of assistance to the production executive. While any number of classifications may be used, these groupings of the duties seem practical:

- Physical Facilities

- Acquisition of plant and equipment

- Proper layout of machinery and equipment, storage facilities, and so on

- Adequate maintenance of plant and equipment

- Proper safeguarding of the physical assets (security)

- Product and Production Planning

- Product design

- Decisions on product specifications

- Determination of material requirements—specifications and quantities

- Selection of manufacturing processes

- Planning the production schedule

- Decisions on manufacturing or purchasing the components—“make-or-buy” decisions

- Material purchases

- Labor-requirements—skill needs, employment, training, and job assignment and transfer

- Inventory levels required

- Preparing the production and manufacturing plans—short and long term

- Manufacturing Process

- Planning and controlling labor

- Receiving, handling, routing, and processing raw materials and work-in-process in an economical manner

- Controlling quality

- Coordinating manufacturing with sales

- Planning and controlling all manufacturing costs—direct and indirect

And the list could go on.

For some phases, the controller may coordinate procedures and see that adequate internal controls exist, that needed economic analysis is made, as in acquisition of plant and equipment or as part of the annual planning process. But perhaps the biggest contribution of the controller is the development and maintenance of a general accounting and cost system that will assist the manufacturing executive, and that will provide the necessary information for the planning and control of the business.

Objectives of Manufacturing Cost Accounting

A manufacturing cost accounting system is an integral part of the total management information system. In analyzing costing systems for control, the controller must recognize the purpose of the manufacturing cost accounting system and relate it to the production or operating management problems. The objectives must be clearly defined if the system is to be effectively utilized. There are four fundamental purposes of a cost system that may vary in importance from one organization to another:

- Control of costs

- Planning and performance measurement

- Inventory valuation

- Deriving anticipated prices

Control of costs is a primary function of manufacturing cost accounting and cost analysis. The major elements of costs—labor, material, and manufacturing expenses—must be segregated by product, by type of cost, and by responsibility. For example, the actual number of parts used in the assembly of an airplane section, such as a wing, may be compared to the bill of materials and corrective action taken when appropriate.

Closely related to cost control is the use of cost data for effective planning and performance measurement. Some of the same information used for cost control purposes may be used for the planning of manufacturing operations. For example, the standards used for cost control of manufacturing expenses can be used to plan these expenses for future periods with due consideration to past experience relative to the established standards. Cost analysis can be utilized, as part of the planning process, to determine the probable effect of different courses of action. Again, a comparison of manufacturing costs versus purchasing a particular part or component can be made in making the determination in make-or-buy decisions. The use of costs and analysis would extend to many facets of the total planning process.

One of the key objectives of a costing system is the determination of product unit cost and the valuation of inventories. This is also a prerequisite to an accurate determination of the cost of goods sold in the statement of income and expense. The manufacturing cost system should recognize this fact and include sufficient cost details, such as layering part costs and quantities for items in inventory, to accomplish this purpose.

A critical purpose of cost data is for establishing selling prices. The manufactured cost of a product is not necessarily the sole determinant in setting prices, since the desired gross margin and the price acceptable to the market are also significant factors. As more companies realize that direct labor and materials are relatively fixed costs, management will concentrate on designing the product to fit a specific price, cost, and gross margin; the controller should be included in this process to advise management about indirect and direct costs.

Controller and Manufacturing Management Problems

A fundamental responsibility of the controller is to ensure that the manufacturing cost systems have been established to serve the needs and requirements of production executives. The controller is the fact finder regarding costs and is responsible for furnishing factory management with sufficient cost information on a timely basis and in a proper format to effect proper control and planning. Unfortunately, under a just-in-time (JIT) system, manufacturing managers need feedback regarding costs far more frequently than on a monthly basis. JIT products are manufactured with little or no wait time, and consequently can be produced in periods far less than was the case under the line manufacturing concept. Therefore, if a cost problem occurred, such as too many direct labor hours required to finish a part, the formal accounting system would not tell the line managers until well after the problem had happened.

Fortunately, JIT principles stress the need to shrink inventories and streamline processes, thereby making manufacturing problems highly visible without any product costing reports. A subset of JIT is cellular (i.e., group) manufacturing, in which equipment is generally arranged in a horseshoe shape, and one employee uses those machines to make one part, taking the piece from machine to machine. Consequently, there is little or no work-in-process (WIP) to track, and any scrapped parts are immediately visible to management. Based on this kind of manufacturing concept, line managers can do without reports, with the exception of daily production quantities versus budgeted quantities that meet quality standards.

Just-in-time manufacturing places the controller in the unique position of looking for something to report on. Since direct labor and materials costs are now largely fixed, the controller's time emphasis should switch to planning the costs of new products, and tracking planned costs versus actual costs. Because the JIT manufacturing environment tends to have small cost variances, the controller should seriously question the amount of effort to be invested in tracking direct labor and materials variances versus the benefit of collecting the data.

Another area in which the controller can profitably invest time tracking information is the number of items that increase a product's cycle time or the non-value-added cost of producing a product. Management can then work to reduce the frequency of these items, thereby reducing the costs associated with them. Here is a partial list of such items:

- Number of material moves

- Number of part numbers used by the company

- Number of setups required to build a product

- Number of products sold by the company, including the number of options offered

- Number of product distribution locations used

- Number of engineering change notices

- Number of parts reworked

If a process is value-added, the controller can initiate an operational audit to find any bottlenecks in the process, thereby improving the capacity of the process. For example, engineering a custom product is clearly value-added; internal auditors could recommend new hardware or software for designing the product to allow the engineering department to design twice as many products with the same number of staff.

Under JIT, there are several traditional performance measures that the controller should be careful not to report:

- If the report is on machine efficiency, then line managers will have an incentive to create an excessive amount of WIP in order to keep their machines running at maximum utilization.

- If the report is on purchase price variances, the materials staff will have an incentive to purchase large quantities of raw materials in order to get volume discounts.

- If the report is on headcount, the manufacturing manager will have an incentive to hire untrained contract workers, who may produce more scrap than full-time, better-trained employees.

- If you include a scrap factor into a product's standard cost, then line managers will take no corrective action unless scrap exceeds the budgeted level, thereby incorporating scrap into the production process.

- If the report is on labor variances, then the accountants will expend considerable labor in an area that has relatively fixed costs and not put time into areas that require more analysis.

- If the report is on standard cost overhead absorption, then management will have an incentive to overproduce to absorb more overhead than was actually expended, thereby increasing profits, increasing inventory, and reducing available cash.

Types of Manufacturing Cost Analyses

The question will arise often about what type of cost data should be presented. Just how should production costs be analyzed? This will depend on the purpose for which the costs are to be used, as well as the cost experience of those who use the information.

Unit costs or total costs may be accumulated in an infinite variety of ways. The primary segregation may be by any one of the following:

| Product or class of product | Process |

| Operation | Customer order |

| Department | Worker responsible |

| Machine or machine center | Cost element |

Each of the primary segregations may be subdivided a number of ways. For example, the out-of-pocket costs may be separated from the “continuing costs,” those that would be incurred whether a particular order or run was made. Again, production costs might be segregated between those which are direct or indirect; that is, those attributable directly to the operation and those prorated. Thus the material used to fashion a cup might be direct, whereas the power used to operate the press would be indirect. Sometimes the analysis of costs will differentiate between those that vary with production volume and those which are constant within the range of production usually experienced. For example, the direct labor consumed may relate directly to volume, whereas depreciation remains unchanged. The controller must use judgment and experience in deciding what type of analysis is necessary to present the essential facts.

The mix of product-cost components has shifted away from direct labor and material dominance to overhead (such as depreciation, materials management, and engineering time). Overhead takes up a greater proportion of a typical product's cost. Because of this change in mix, the controller will find that product cost analyses will depend heavily on how to assign overhead costs to a product. Activity-based costing (ABC) is of considerable use in this area. For more information about ABC, refer to Chapter 5.

Types of Cost Systems

Experience in cost determination in various industries and specific companies has given rise to several types of cost systems that best suit the kinds of manufacturing activities. A traditional costing system known as a “job order cost system” is normally used for manufacturing products to a specific customer order or unique product. For example, the assembly or fabrication operations of a particular job or contract are collected in a separate job order number. Another widely used costing system is known as a “process cost system.” This system assigns costs to a cost center rather than to a particular job. All the production costs of a department are collected, and the departmental cost per unit is determined by dividing the total departmental costs by the number of units processed through the department. Process cost systems are more commonly used in food processing, oil refining, flour milling, paint manufacturing, and so forth. No two cost accounting systems are identical. There are many factors that determine the kind of system to use, such as product mix, plant location, product diversity, number of specific customer orders, and complexity of the manufacturing process. It may be advisable to combine certain characteristics of both types of systems in certain situations. For example, in a steel mill the primary system may be a process cost system; however, minor activities such as maintenance may be on a job cost basis. The controller should thoroughly analyze all operations to determine the system that best satisfies all needs.

There are two issues currently affecting the job order and process costing systems of which the controller should be aware:

- JIT manufacturing systems allow the controller to reduce or eliminate the recordkeeping needed for job cost reporting. Since JIT tends to eliminate variances on the shop floor by eliminating the WIP that used to mask problems, there are few cost variances for the cost accountant to accumulate in a job cost report. Therefore, the time needed to accumulate information for job costing may no longer be worth the increase in accuracy derived from it, and the controller should consider using the initial planned job cost as the actual job cost.

- One of the primary differences between process and job-shop costing systems is the presence (job shop) or absence (process flow) of WIP. Since installing a JIT manufacturing system inherently implies reducing or eliminating WIP, a JIT job-shop costing system may not vary that much from a process costing system.

Factory Accounts and General Accounts

The selection of the manufacturing cost accounting system should recognize the relation-ship of the factory cost accounts to the general accounts. Normally, the factory accounts should be tied into the general accounts for control purposes. It should enhance the accuracy of the cost information included in the top-level manufacturing cost reports as well as the profit or loss statements and balance sheet. Periodic review and reconciliation of the accounts will also minimize unexpected or year-end adjustments. This integration of the cost accounts is extremely important as the company expands and the operations are more complex.

Although there are situations where the factory and general accounts are not coordinated, it is not recommended. If such a system is used additional effort is required to ensure the accuracy and preclude misstatement of cost information. Such a procedure requires extreme care in cutoffs for liabilities and the taking of physical inventories as well as analyzing inventory differences.

DIRECT MATERIAL COSTS: PLANNING AND CONTROL

Scope of Direct Material Involvement

Direct material, as the term is used by cost accountants, refers to material that can be definitely or specifically charged to a particular product, process, or job, and that becomes a component part of the finished product. The definition must be applied in a practical way, for if the material cannot be conveniently charged as direct or if it is an insignificant item of cost, then it would probably be classified as indirect material and allocated with other manufacturing expenses to the product on some logical basis. Although this section deals primarily with direct material, certain of the phases relate also to indirect material.

In its broadest phase, material planning and control is simply the providing of the required quantity and quality of material at the required time and place in the manufacturing process. By implication, the material secured must not be excessive in amount, and it must be fully accounted for and used as intended. The extent of material planning and control is broad and should cover many phases or areas, such as plans and specifications; purchasing; receiving and handling; inventories; usage; and scrap, waste, and salvage. In each of these phases, the controller has certain responsibilities and can make contributions toward an efficient operation.

Benefits from Proper Material Planning and Control

Because material is such a large cost item in most manufacturing concerns, effective utilization is an important factor in the financial success or failure of the business. Proper planning and control of materials with the related adequate accounting has the following ten advantages:

- Reduces inefficient use or waste of materials

- Reduces or prevents production delays by reason of lack of materials

- Reduces the risk from theft or fraud

- Reduces the investment in inventories

- May reduce the required investment in storage facilities

- Provides more accurate interim financial statements

- Assists buyers through a better coordinated buying program

- Provides a basis for proper product pricing

- Provides more accurate inventory values

- Reduces the cost of insurance for inventory

Defining and Measuring Direct Material Costs

There is some confusion regarding what costs can be itemized as direct materials. This section defines the various cost elements and explains why some costs are categorized as direct materials and others are not.

It is common to charge any material that is listed on a product's bill of materials (BOM) to that product as a direct material cost. If there is no BOM, then it may be necessary to physically break down a product to determine the types and quantities of its component parts. Though this definition seems simple enough, there are a variety of peripheral costs to consider:

- Discounts. It is reasonable to deduct discounts from suppliers from the cost of direct materials, because there is a direct and clearly identifiable relationship between the discount and the payment for the materials.

- Estimates. It is reasonable to credit or debit material costs if the estimates are based on calculations that can be easily proved through an audit. For example, it may be easier to allocated purchase discounts to specific materials than to credit them individually; if so, there should be a calculation that bases the estimated credit on past discounts for specific materials.

- Freight. It is reasonable to include the freight cost of bringing materials to the production facility, because this cost is directly related to the materials themselves. However, outbound freight costs should not be included in direct materials, because this cost is more directly related to sales or logistics than to manufacturing.

- Packaging costs. It is reasonable to include packaging costs in direct materials if the packaging is a major component of the final product. For example, perfume requires a glass container before it is sold, so the glass container should be included in the direct materials cost. This should also include packing supplies.

- Samples and tests. It is reasonable to include the cost of routine samples and tests in direct materials. For example, the quality assurance staff may pull a specific number of products from the production line for destructive testing; this is a standard part of the production process, so the materials lost should still be recorded as direct materials.

- Scrap. It is reasonable to include the cost of scrap in direct materials if it is an ongoing and fairly predictable expense. For example, there is a standard amount of liquid evaporation to be expected during the processing of some products, while other products will require a percentage of scrap when raw materials are used to create the finished product. However, an inordinate level of scrap that is above usual expectations should be expensed off separately and immediately as scrap, since it is not an ongoing part of the production process. If there is some salvage value to scrapped materials, this amount should be an offset to the direct materials cost.

- Indirect materials costs. There are a number of costs that are somewhat related to materials costs, but which cannot be charged straight to direct materials because of accounting rules. These costs include the cost of warehousing, purchasing, and distribution. Instead, these costs can be combined into one or more cost pools and allocated to products based on the proportion of usage of the expenses in those cost pools.

Planning for Direct Material

The planning aspect of direct material relates to four phases, budgets, or plans:

- Material usage budget. This budget involves determining the quantities and related cost of the raw materials and purchased parts needed to meet the production budget (quantities of product to be manufactured) on a time-phased basis. Basically it is a matter of multiplying the volume of finished articles to be produced times the number of individual components needed for its manufacture. This determination is the responsibility of the manufacturing executive. However, the aggregate costs must be provided to the controller in an appropriate format. In most instances, it will be under the direction of the controller that the planning procedure and format of exhibits required will be established. The controller requires the total cost, by time period, to provide for the charge to work-in-process inventory and for relief of raw materials and purchased parts inventory in the financial planning process of preparing the business plan for the year or for other planning periods. Obviously, the material usage budget must be known so that the required purchases can be made and the required inventory level maintained.

The determination of the material usage budget is described in more detail in Chapter 10 on inventory planning and control.

The material usage budget generally will be summarized by physical quantities of significant items for use by manufacturing personnel. A cost summary is needed by the controller for preparing the plan in monetary terms. The usage budget may be presented in any one of several ways. A time-phased summary by major category of raw material for a small aircraft manufacturer is illustrated in Exhibit 4.1.

EXHIBIT 4.1 SUMMARIZED MATERIAL USAGE BUDGET

- Material purchases budget. When the material usage budget is known, the purchases budget can be determined (by the purchasing department), taking into account the required inventory levels.

The time-phased material purchases budget is provided by the purchasing director (usually reporting to the manufacturing executive) to the controller for use in planning cash disbursements, and additions to the raw materials and purchased parts inventories—as part of the annual planning process (or planning for any other period). A highly condensed raw material purchases budget for the annual plan is illustrated in Exhibit 4.2.

- Finished production budget. This represents the quantities of finished product to be manufactured in the planning period. Such estimates are provided by the manufacturing executive to the controller for determining the additions to the finished goods inventory and the relief to the work-in-process inventory.

The quantities of production usually are costed by the cost department under the supervision of the controller.

- Inventories budgets. The three preceding budgets, plus the cost-of-goods-sold budget, determine the inventory budgets for the planning period. In the annual planning process, the inventory costs usually are determined monthly.

Inventory budgets, together with the related purchases, usage, and completed product, are shown in Chapter 10 on planning and control of inventories.

While the raw materials, purchased parts, and work-in-process budgets usually are the responsibility of the manufacturing executive, and the finished goods budget is the responsibility of either the manufacturing executive or the sales executive, the controller has certain reporting functions (see Chapter 10) as to planned versus actual inventory levels and turnover rates, as well as responsibility for the adequacy of the internal control system.

To summarize, any planning responsibilities for direct materials rest with other line executives, although the controller will use these related data in the financial planning process—in preparing the statement of estimated income and expense, the statement of estimated financial condition, and statement of estimated cash flows. Also, the controller will often test-check or audit the information furnished by the manufacturing executive for completeness, reasonableness, and compatibility with other plans. On occasion, the chief manufacturing executive will request the controller and staff to assemble the needed figures, with the help of the production staff.

EXHIBIT 4.2 SUMMARIZED RAW MATERIAL PURCHASE BUDGET

The various budgets related to materials generally will be developed following a procedure and format coordinated (and sometimes developed by) the controller.

Those interested in a more detailed explanation of developing the plans or budgets for raw material usage and purchases may wish to check some of the current literature.

Basic Approach to Direct Material Cost Control

With an overview of the planning function behind us, we can now review the control function. With respect to materials, as with other costs, control in its simplest form involves the comparison of actual performance with a measuring stick—standard performance—and the prompt follow-up of adverse trends. However, it is not simply a matter of saying “350 yards of material were used, and the standard quantity is only 325” or “The standard price is $10.25 but the actual cost to the company was $13.60 each.” Many other refinements or applications are involved. The standards must be reviewed and better methods found. Or checks and controls must be exercised before the cost is incurred. The central theme, however, is still the use of a standard as a point of measurement.

Although the applications will vary in different concerns, some of the problems or considerations that must be handled by the controller are:

- Purchasing and receiving

- Establishment and maintenance of internal checks to assure that materials paid for are received and used for the purpose intended. Since some purchases are now received on a just-in-time basis, the controller may find that materials are now paid for based on the amount of product manufactured by the company in a given period, instead of on a large quantity of paperwork associated with a large number of small-quantity receipts.

- Audit of purchasing procedures to ascertain that bids are received where applicable. A JIT manufacturing system uses a small number of long-term suppliers, however, so the controller may find that bids are restricted to providers of services such as janitorial duties and maintenance activities.

- Comparative studies of prices paid for commodities with industry prices or indexes.

- Measurement of price trends on raw materials. Many JIT supplier contracts call for price decreases by suppliers at set intervals; the controller should be aware of the terms of these contracts and audit the timing and amount of the changes.

- Determination of price variance on current purchases through comparison of actual and standard costs. This may relate to purchases at the time of ordering or at time of receipt. The same approach may be used in a review of current purchase orders to advise management in advance about the effect on standard costs. In a JIT environment, most part costs would be contractually set with a small number of suppliers, so the controller would examine prices charged for any variations from the agreed-upon rates.

- Usage

- Comparison of actual and standard quantities used in production. A variance may indicate an incorrect quantity on the product's bill of materials, misplaced parts, pilferage, or incorrect part quantities recorded in inventory.

- Preparation of standard cost formulas (to emphasize major cost items and as part of a cost reduction program).

- Preparation of reports on spoilage, scrap, and waste as compared with standard. In a JIT environment, no scrap is allowed for and therefore is not included in the budget as a standard.

- Calculation of costs to make versus costs to buy.

This list suggests only some of the methods available to the controller in dealing with material cost control.

Setting Material Quantity Standards

Because an important phase of material control is the comparison of actual usage with standard, the controller is interested in the method of setting these quantitative standards. First, assistance can be rendered by contributing information about past experience. Second, the controller should act as a check in seeing that the standards are not so loose that they bury poor performance, on the one hand, and represent realistic but attainable performance, on the other.

Standards of material usage may be established by at least three procedures:

- By engineering studies to determine the best kind and quality of material, taking into account the product design requirements and production methods

- By an analysis of past experience for the same or similar operations

- By making test runs under controlled conditions

Although a combination of these methods may be used, best practice usually dictates that engineering studies be made. To the theoretical loss must be added a provision for those other unavoidable losses that it is impractical to eliminate. In this decision, past experience will play a part. Past performance alone, of course, is not desirable in that certain known wastes may be perpetuated. This engineering study, combined with a few test runs, should give fairly reliable standards.

Revision of Material Quantity Standards

Standards are based on certain production methods and product specifications. It would be expected, therefore, that these standards should be modified as these other factors change, if such changes affect material usage. For the measuring stick to be an effective control tool, it must relate to the function being measured. However, the adjustment need not be carried through as a change in inventory value, unless it is significant.

Using Quantity Standards for Cost Control

The key to material quantity control is to know in advance how much material should be used on the job, frequently to secure information about how actual performance compares with standard during the progress of the work, and to take corrective action where necessary. The supervisor responsible for the use of materials, as well as the superior, should be aware of these facts. At the lowest supervisory level, details of each operation and process should be in the hands of those who can control usage. At higher levels, only overall results need be known.

The method to be used in comparing the actual and standard usage will differ in each company, depending on several conditions. Some of the more important factors that will influence the controller in applying control procedures about material usage are:

- The production method in use

- The type and value of the materials

- The degree to which cost reports are utilized by management for cost control purposes

A simple excess material report that is issued daily is shown in Exhibit 4.3. It shows not only the type of material involved as excess usage, but also the cause of the condition. This report could be available on a real-time basis, with the use of a computer, and could be summarized daily for the plant manager.

One of the most important considerations is the nature of the production process. In a job order or lot system, such as an assembly operation in an aircraft plant, where a definite quantity is to be produced, the procedure is quite simple. A production order is issued, and a bill of material or “standard requisition” states the exact quantity of material needed to complete the order. If parts are spoiled or lost, it then becomes necessary to secure replacements by means of a nonstandard or excess usage requisition. Usually, the foreman must approve this request, and, consequently, the excess usage can be identified immediately. A special color (red) requisition may be used, and a summary report issued at certain intervals for the use of the production executives responsible.

If production is on a continuous process basis, then periodically a comparison can be made of material used in relation to the finished product. Corrective action may not be as quick here, but measures can be taken to avoid future losses.

EXHIBIT 4.3 DAILY EXCESS MATERIAL USAGE REPORT

Just as the production process is a vital factor in determining the cost accounting plan, so also it is a consideration in the method of detecting material losses. If losses are to be localized, then inspections must be made at selected points in the process of manufacture. At these various stations, the rejected material can be counted or weighed and costed if necessary. When there are several distinct steps in the manufacturing process, the controller may have to persuade the production group of the need and desirability of establishing count stations for control purposes. Once these stations are established, the chief contribution of the accountant is to summarize and report the losses over standard. The process can be adopted to the use of personal computers and provision of control information on a real-time basis.

Another obvious factor in the method of reporting material usage is the type and value of the item itself. A cardinal principle in cost control is to place primary emphasis on high-value items. Hence, valuable airplane motors, for example, would be identified by serial number and otherwise accurately accounted for. Items with less unit value, or not readily segregated, might be controlled through less accurate periodic reporting. An example might be lumber. The nature and value of the materials determine whether the time factor or the unit factor would be predominant in usage reporting.

Management is often not directly interested in dollar cost for control purposes but rather only in units. There is no difference in the principle involved but merely in the application. Under these conditions, the controller should see that management is informed of losses in terms of physical units—something it understands. In this case, the cost report would be merely a summary of the losses. Experience will often show, however, that as the controller gives an accounting in dollars, the other members of management will become more cost conscious.

The essence of any control program, regardless of the method of reporting, however, is to follow up on substandard performance and take corrective action.

A variation on using quantity standards and materials variation reporting is JIT variance reporting. One of the cornerstones of the JIT concept is that you order only what you need. That means you won't waste what you use and that there should be no materials variances. Of course, even at world-class JIT practitioners such as Motorola and Toyota, there is scrap; however, there is much less than will be found at a non-JIT company. Consequently, the controller must examine the cost of collecting the variance information against its value in correcting the amount of scrap accumulation. The conclusion may be that JIT does not require much materials variance reporting, if any.

Limited Usefulness of Material Price Standards

In comparing actual and standard material costs, the use of price standards permits the segregation of variances as a result of excess usage from those incurred by reason of price changes. By and large, however, the material price standards used for inventory valuation cannot be considered as a satisfactory guide in measuring the performance of the purchasing department. Prices of materials are affected by so many factors outside the business that the standards represent merely a measure of what prices are being paid as compared with what was expected to be paid.

A review of price variances may, however, reveal some informative data. Exceedingly high prices may reveal special purchases for quick delivery because someone had not properly scheduled purchases. Or higher prices may reveal shipment via express when freight shipments would have been satisfactory. Again, the lowest cost supplier may not be utilized because of the advantages of excellent quality control methods in place at a competitive shop. The total cost of production and impact on the marketplace needs to be considered—not merely the purchase price of the specific item. To generalize, the exact cause for any price variance must be ascertained before valid conclusions can be drawn. Some companies have found it advisable to establish two standards—one for inventory valuation and quite another to be used by the purchasing department as a goal to be attained. One negative result of recording a purchase price variance is that the purchasing department may give up close supplier relationships in order to get the lowest part cost through the bidding process. Part bidding is the nemesis of close supplier parings (a cornerstone of JIT), since suppliers know they will be kicked off the supplier list, no matter how good their delivery or quality, unless they bid the lowest cost.

Setting Material Price Standards

Practice varies somewhat about the responsibility for setting price standards. Sometimes the cost department assumes this responsibility on the basis of a review of past prices. In other cases, the purchasing staff gives its estimate of expected prices that is subject to a thorough and analytical check by the accounting staff. Probably, the most satisfactory setup is through the combined effort of these two departments.

Other Applications of Material Control

By using a little imagination, every controller will be able to devise simple reports that will be of great value in material control—whether in merely making the production staff aware of the high-cost items of the product or in stimulating a program of cost reduction. For example, in a chemical processing plant, a simple report detailing the material components cost of a formulation could be used to advantage. Another report is illustrated in Exhibit 4.4, wherein the standard material cost of an assembly-type operation, in this case a self-guided small plane, is given

Where the products are costly, and relatively few in number, it may be useful to provide management periodically with the changes in contracted prices, as well as an indication about the effect of price changes on the planned cost of the product. Such statements may stimulate thinking about material substitutions or changes in processes or specifications.

LABOR COSTS: PLANNING AND CONTROL

Labor Accounting under Private Enterprise

One of the most important factors in the success of a business is the maintenance of a satisfactory relationship between management and employees. Controllers as well as their staff can do much to encourage and promote such a relationship, whether it is such a simple matter as seeing that the payroll checks are ready on time or whether it extends to the development of a wage system that rewards meritorious performance.

Aside from this fact, labor accounting and control are important. As automation and the use of robots and computers become even more prevalent, what was once called direct labor may not any longer increase in relative importance. But labor is still a significant cost. Likewise, those costs usually closely related to labor costs have grown by leaps and bounds—costs for longer vacations, more adequate health and welfare plans, pension plans, and increased Social Security taxes. These fringe benefit costs are 50% or more of many payrolls. For all these reasons, the cost of labor is an important cost factor.

EXHIBIT 4.4 DETAIL OF, AND CHANGES IN, STANDARD MATERIAL COSTS

The three objectives of labor accounting are outlined as:

- A prompt and accurate determination of the amount of wages due the employee.

- The analysis and determination of labor costs in such a manner as may be needed by management (e.g., by product, operation, department, or category of labor) for planning and control purposes.

- The advent of JIT manufacturing systems has called into question the need for reporting the direct labor utilization variance. This variance revolves around the amount of a product that is produced with a given amount of labor; thus, a positive labor utilization variance can be achieved by producing more product than may be needed. An underlying principle of JIT is to produce only as much as is needed to produce, so JIT and labor utilization variance reporting are inherently at odds with each other. If JIT has been installed, then the controller should consider eliminating this type of variance reporting.

Classification of Labor Costs

With the increasing trends to automation, to continuous process type of manufacturing, and to integrated machine operations under which individual hand operations are replaced, the traditional accounting definition of direct labor must be modernized. As a practical matter, where labor is charged to a cost center and is directly related to the main function of that center, whether it is direct or indirect labor is of no consequence. Rather, attention must be directed to labor costs. Perhaps the primary considerations are measurability and materiality rather than physical association with the product. For planning and control purposes, any factory wages or salaries that are identifiable with a directly productive department as contrasted with a service department and are of significance in that department are defined as manufacturing labor.

All other labor will be defined as indirect labor, treated as overhead expense, and discussed under manufacturing expenses.

Expanded Definition of Direct Labor

Direct labor is that labor which is traceable to the manufacturing of products or the provision of services for consumption by a customer. This cost includes incidental time that is part of a typical working day, such as break time, but does not include protracted down time for nonrecurring activities, such as training or downtime caused by machine failures. Direct labor should also include those benefits costs that are “part and parcel” of the direct labor worker, such as medical and dental insurance costs, production-related bonuses, FICA, cost of living allowances, workers' compensation insurance, vacation and holiday pay, unemployment compensation insurance, and pension costs. Overtime bonuses should also be included in direct labor costs. It is also acceptable to track labor costs as standard costs, as long as one periodically writes off the difference between standard and actual direct labor costs, so that there is no long-term difference between the two types of labor costs. These are the components of direct labor.

Direct labor is only that labor that adds value to the product or service. However, there are many activities in the manufacturing or service areas, not all of which add value to the final product, so one must be careful to segregate costs into the direct labor and indirect labor categories. Direct labor is typically incurred during the fabrication, processing, assembly, or packaging of a product or service. Alternatively, any labor incurred to maintain or supervise the production or service facility is categorized as indirect labor.

There are several costs that should not be included in direct labor. These are excluded because they do not directly trace back to work on products or services, nor are they a standard part of a direct labor worker's benefits package. These costs include the maintenance of recreational facilities for employees, any company-sponsored meal plans, membership dues in outside organizations, separation allowances, and safety-related expenses. These costs are typically either charged off to current expenses, or else rolled into overhead costs.

Planning of Labor Costs

Planning labor costs might be described as planning or estimating the required manpower and costs associated with direct manufacturing departments (not indirect) for the annual plan or some other relevant planning period. It consists of determining the labor planning budget.

The process, which is essentially the responsibility of the manufacturing executive, consists of extrapolating the planned production of units times the standard labor content, plus an allowance for variances, to arrive at the labor hours required. This is a tedious job, but the computer as applied to the standard labor hour content of expected production makes it much easier. Essentially, this process has several purposes, such as:

- Ascertaining by department, by skill, and by time period the number and type of workers needed to carry out the production program for the planning horizon

- Determining the labor cost for the production program, including: labor input, labor content of completed product, and labor content of work-in-process. These data may then be used by the controller for determining the transfers to/from work-in-process and finished goods—in the same manner material costs were accounted for.

- Determining the estimated cost (payroll) requirements of the time-phased manufacturing labor budget for the planning period

- Determining the unit labor content of each product so that the inventory values, cost of manufacturer, and cost of sales can be calculated for use in the statements of planned income and expense, planned financial condition, and planned cash flows

- Seeing that the planned funds are available to meet the payroll

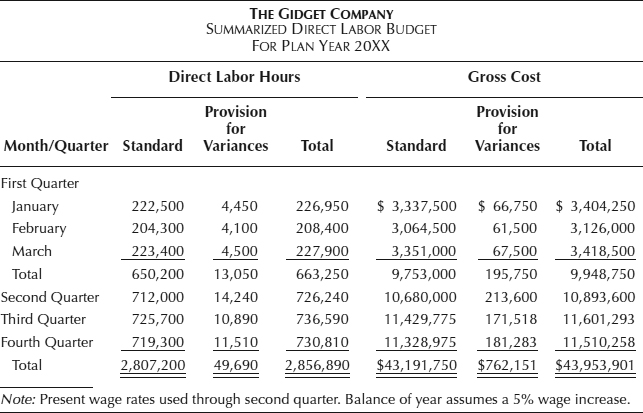

A summarized direct labor budget for annual planning purposes, based on the underlying required labor hours by department, by product, and time-phased, might appear as in Exhibit 4.5.

A JIT manufacturing environment creates significant changes in direct labor costs that the controller should be aware of. When a manufacturing facility changes from an assembly line to manufacturing cells, the labor efficiency level drops, because machine setups become more frequent. A major JIT technique is to reduce setup times to minimal levels, but nonetheless, even the small setup times required for cellular manufacturing require more labor time than the zero setup times used in long assembly line production runs. Consequently, if management is contemplating switching to cellular manufacturing, the controller should expect an increase in the labor hours budget. Also, if the labor cost does not increase, the controller should see if the engineering staff has changed the labor routings to increase the number of expected setup times.

To the extent more information is desired on the planning aspects of direct labor, the reader may wish to consult some of the books on the subject.1

EXHIBIT 4.5 SUMMARIZED DIRECT LABOR BUDGET

Controller's Contribution to Control

In controlling direct labor costs, as with most manufacturing costs, the ultimate responsibility must rest with the line supervision. Yet this group must be given assistance in measuring performance, and certain other policing or restraining functions must be exercised. Herein lie the primary duties of the controller's organization. Among the means at the disposal of the chief accounting executive for labor control are the following seven:2

- Institute procedures to limit the number of employees placed on the payroll to that called for by the production plan.

- Provide preplanning information for use in determining standard labor crews by calculating required standard labor-hours for the production program.

- Report hourly, daily, or weekly standard and actual labor performance.

- Institute procedures for accurate distribution of actual labor costs, including significant labor classifications to provide informative labor cost analyses.

- Provide data on past experience with respect to the establishment of standards.

- Keep adequate records on labor standards and be on the alert for necessary revisions.

- Furnish other supplementary labor data reports, such as:

- (a) Hours and cost of overtime premium, for control of overtime

- (b) Cost of call-in pay for time not worked to measure efficiency of those responsible for call-in by union seniority

- (c) Comparative contract costs, that is, old and new union contracts

- (d) Average hours worked per week, average take-home pay, and similar data for labor negotiations

- (e) Detailed analysis of labor costs over or under standard

- (f) Statistical data on labor turnover, length of service, training costs

- (g) Union time—cost of time spent on union business

Setting Labor Performance Standards

The improvement of labor performance and the parallel reduction and control of costs require labor standards—operating time standards and the related cost standards. Setting labor performance standards is a highly analytical job that requires a technical background of the production processes as well as a knowledge of time study methods. This may be the responsibility of a standards department, industrial engineering department, or cost control department. Occasionally, although rarely, it is under the jurisdiction of the controller. Establishment of the standard operation time requires a determination of the time needed to complete each operation when working under standard conditions. Hence this study embodies working conditions, including the material control plan, the production planning and scheduling procedure, and layout of equipment and facilities. After all these factors are considered, a standard can be set by the engineers.

In using time standards for measuring labor performance the accounting staff must work closely with the industrial engineers or those responsible for setting the standards. The related cost standards must be consistent; the accumulation of cost information must consider how the standards were set and how the variances are analyzed.

The following discussion on labor standards does not apply to a JIT manufacturing environment, especially one that uses cellular (i.e., group) manufacturing layouts. Labor utilization standards can be improved by increasing the amount of production for a set level of labor, and this is considered to be good in an assembly line environment. Under JIT, however, producing large quantities of parts is not considered acceptable; under JIT, good performance is producing the exact quantity of parts that are needed, and doing so with quality that is within preset tolerance levels. Once the correct quantity of parts are produced, the direct labor staff stops production; this creates unfavorable labor utilization variances. Therefore, measuring a JIT production facility with a labor utilization variance would work against the intent of JIT, since the production manager would have an incentive to produce more parts than needed, and would not be mindful of the part quality.

Revision of Labor Performance Standards

Generally, performance standards are not revised until a change of method or process occurs. Since standards serve as the basis of control, the accounting staff should be on the alert for changes put into effect in the factory but not reported for standard revision. If the revised process requires more time, the production staff will usually make quite certain that their measuring stick is modified. However, if the new process requires less time, it is understandable that the change might not be reported promptly. Each supervisor naturally desires to make the best possible showing. The prompt reporting of time reductions might be stimulated through periodic review of changes in standard labor hours or costs. In other words, the current labor performance of actual hours compared to standard should be but one measure of performance; another is standard time reductions, also measured against a goal for the year.

It should be the responsibility of the controller to see that the standards are changed as the process changes to report true performance. If a wage incentive system is related to these standards, the need for adjusting process changes is emphasized. An analysis of variances, whether favorable or unfavorable, will often serve to indicate revisions not yet reported.

Although standard revisions will often be made for control purposes, it may not be practical or desirable to change product cost standards. The differences may be treated as cost variances until they are of sufficient magnitude to warrant a cost revision.

Operating under Performance Standards

Effective labor control through the use of standards requires frequent reporting of actual and standard performance. Furthermore, the variance report must be by responsibility. For this reason the report on performance is prepared for each foreman as well as the plant superintendent. The report may or may not be expressed in terms of dollars. It may compare labor-hours or units of production instead of monetary units. But it does compare actual and standard performance.

Some operations lend themselves to daily reporting. Through the use of computer equipment or other means, daily production may be evaluated and promptly reported on. A simple form of daily report, available to the plant superintendent by 8:00 A.M. for the preceding day's operations, is shown in Exhibit 4.6. With the use of computers, this data can be made available, essentially on a real-time basis.

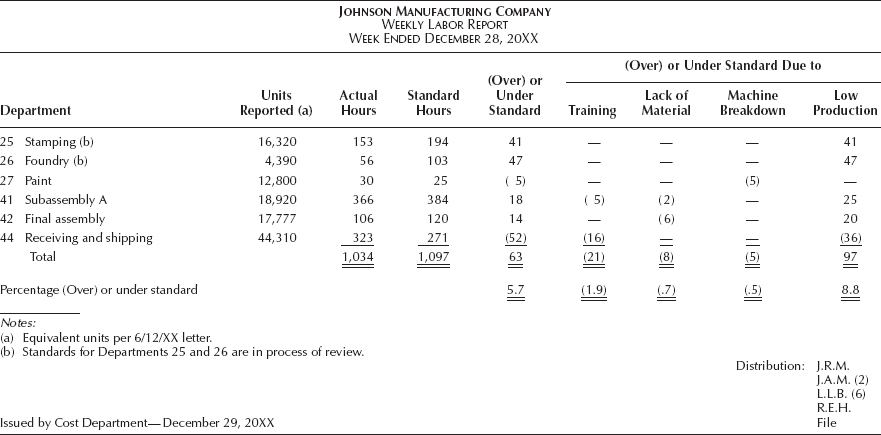

If required, the detail of this summary report can be made available to indicate on what classification and shift the substandard operations were performed. Another report, issued weekly, that details the general reason for excess labor hours is illustrated in Exhibit 4.7.

In a JIT environment, the manufacturing departments are tightly interlocked with minimal WIP between each department to cover for reduced staff problems. In other words, if an area is understaffed, then downstream work stations will quickly run short of work. Consequently, the most critical direct labor measure in a JIT environment is a report of absent personnel, delivered promptly to the production managers at the start of the work day, so they can reshuffle the staff to cover all departments, and contact the missing personnel.

EXHIBIT 4.6 SAMPLE DAILY REPORT

EXHIBIT 4.7 WEEKLY LABOR REPORT

Use of Labor Rate Standards

Generally speaking, labor rates paid by a company are determined by external factors. The rate standard used is usually that normally paid for the job or classification as set by collective bargaining. If standards are set under this policy, no significant variances should develop because of base rates paid. There are, however, some rate variances that may be created and are controllable by management. Some of these reasons, which should be set out for corrective action, include:

- Overtime in excess of that provided in the standard

- Use of higher-rated classifications on the job

- Failure to place staff on incentive

- Use of crew mixture different from standard (more higher classifications and fewer of the lower)

The application of the standard labor rate to the job poses no great problem. Usually, this is performed by the accounting department after securing the rates from the personnel department. Where overtime is contemplated in the standard, it is necessary, of course, to consult with production to determine the probable extent of overtime for the capacity at which the standard is set.

It should be mentioned that the basic design of the product will play a part in control of costs by establishing the skill necessary and therefore the job classification required to do the work.

Control through Preplanning

The use of the control tools previously discussed serves to point out labor inefficiencies after they have happened. Another type of control requires a determination about what should happen and makes plans to assure, to the extent possible, that it does happen. It is forward looking and preventive. This approach embodies budgetary control and can be applied to the control of labor costs. For example, if the staff requirements for the production program one month hence can be determined, then steps can be taken to make certain that excess labor costs do not arise because too many people are on the payroll. This factor can be controlled; thus the remaining factors are rate and quality of production and overtime. Overtime costs can be held within limits through the use of authorization slips.

The degree to which this preplanning can take place depends on the industry and particular conditions within the individual business firm. Are business conditions sufficiently stable so that some reasonably accurate planning can be done? Can the sales department indicate with reasonable accuracy what the requirements will be over the short run? An application might be in a machine shop where thousands of parts are made. If production requirements are known, the standard labor hours necessary can be calculated and converted to staff hours. The standard labor hours may be stored in a computer by skills required and by department. After evaluating the particular production job, an experienced efficiency factor may be determined. Thus, if 12,320 standard labor hours are needed for the planned production but an efficiency rate of only 80% is expected, then 15,400 actual labor hours must be scheduled. This requires a crew of 385 people (40 hours per week). This can be further refined by skills or an analysis made of the economics of some overtime. Steps should be taken to assure that only the required number is authorized on the payroll for this production. As the requirements change, the standard labor hours should be reevaluated.

In an Manufacturing Resource Planning II environment, labor routings must be at least 95% accurate, and the firm must strictly adhere to a master production schedule. If the controller works in such an environment, then labor requirements can easily be predicted by multiplying the related labor routings by the unit types and quantities shown on the master schedule.

There are many computer-based labor control systems available for adoption to particular or specific needs. The controller or accounting staff should be familiar with the various systems so that labor costs are controlled and performance reported in a timely and accurate manner.

Labor Accounting and Statutory Requirements

One of the functions of a controller is to ensure that the company maintains the various pay-roll and other records required by various federal and state government agencies, including the IRS. It is mandatory that the employee's earning records be properly and accurately maintained, including all deductions from gross pay. The required reports must be submitted, and withheld amounts transmitted to the appropriate agencies. It is not the purpose of this book to discuss in detail these reporting requirements, since many publications are available to the controller on this subject.

Wage Incentive Plans: Relationship to Cost Standards

In an effort to increase efficiency, a number of companies have introduced wage incentive plans—with good results. The controller is involved through the payroll department, which must calculate the amount. The controller's responsibilities for the system are best left to authorities on the subject. One facet, however, is germane to the costing process and should be discussed. When an incentive wage plan is introduced into an operation already on a standard cost basis, a problem arises about the relationship between the standard level at which incentive earnings commence and the standard level used for costing purposes. Moreover, what effect should the wage incentive plan have on the standard labor cost and standard manufacturing expense of the product? To cite a specific situation, a company may be willing to pay an incentive to labor for performance that is lower than that assumed in the cost standard (but much higher than actual experience). If such a bonus is excluded from the cost standard, the labor cost at the cost standard level will be understated. Further, there may be no offsetting savings in manufacturing expenses since the costs are incurred to secure performance at a lower level than the cost standard. These statements assume that the existing cost standard represents efficient performance even under incentive conditions. However, if the effect of the incentive plan is to increase sustained production levels well above those contemplated in the cost standards, it may be that the product will be over-costed by using present cost standards and that these standards are no longer applicable. How should the cost standards be set in relation to the incentive plan?

In reviewing the problem, several generalizations may be made. First, there is no necessary relationship between standards for incentive purposes and standards for costing purposes. The former are intended to stimulate effort, whereas the latter are used to determine what the labor cost of the product should be. One is a problem in personnel management, whereas the other is strictly an accounting problem. With such dissimilar objectives, the levels of performance could logically be quite different.

Then, too, the matter of labor costing for statement purposes should be differentiated from labor control. As we have seen, labor control may involve nonfinancial terms—pieces per hour, pounds per labor hour, and so on. Labor control can be accomplished through the use of quantitative standards. Even if costs are used, the measuring stick for control need not be the same as for product costing. Control is centered on variations from performance standards and not on product cost variations.

A thorough consideration of the problem results in the conclusion that labor standards for costing purposes should be based on normal expectations from the operation of a wage incentive system under standard operating conditions. The expected earnings under the bonus plan should be reflected in the standard unit cost of the product. It does not necessarily follow that the product standard cost will be higher than that used before introduction of the incentive plan. It may mean, however, that the direct labor cost will be higher by reason of bonus payments. Yet, because of increased production and material savings, the total unit standard manufacturing cost should be lower.