9

PLANNING AND CONTROL OF RECEIVABLES

INTRODUCTION

The typical goals of the accounts receivable area are to keep the receivable amount as low as possible, in order to reduce working capital needs, while reducing bad debts to a very low level. Unfortunately, a controller may also be subjected to the opposing pressure of granting very high credit levels to customers in order to spur revenue growth, which inevitably leads to high levels of accounts receivable and larger amounts of bad debt. Although it is not possible to fully reconcile these conflicting goals and instructions, this chapter describes a number of methods for setting up rational systems for granting credit, analyzing customers, and collecting funds from them. In addition, a number of control methods for ensuring that established credit levels are strictly followed are discussed, as well as how to predict the investment in accounts receivable for budgeting purposes. In short, this chapter describes how to control accounts receivable and predict receivable levels.

GRANTING CREDIT TO CUSTOMERS

When reducing the amount of accounts receivable outstanding, it is best to view the collections process as a funnel. The collections person is dealing with a continuous stream of poor credit risks that are emerging from a funnel full of accounts receivable. Going into the other end of the funnel are sales to customers; unless those sales are filtered somehow, there will be an unending stream of potential bad debt problems. Clearly, then, the best way to avoid collection problems is to pay strict attention to the process of granting credit to customers before the company ever sells them anything. This section discusses the issues related to the important process of granting credit to customers.

First of all, why grant credit to a customer? Some companies insist on cash payments, but they find that this limits the number of customers who are willing to deal with them. Thus, granting credit widens the range of potential customers. Another reason is that many customers view credit terms as part of the price of the product, and may pay more for a product if a company is willing to grant generous credit terms. Yet another reason is that some industries have a customary number of payment days, and a company will be viewed as “playing hardball” if it demands cash payments at the time of delivery. Consequently, there are a variety of good reasons to grant credit to customers.

However, there are a number of pitfalls that a company must be mindful of when granting credit. Some are so important that a company can be dragged into bankruptcy if it does not closely monitor the process. One danger is of granting too much credit to customers, because this may seriously reduce the amount of available working capital that a company has available for other purposes. Another danger is that improper review of customer financial statements or payment history may result in the extension of credit that results in large bad debts. Either problem can reduce a company's available credit to the point where it cannot issue credit to good customers who deserve to have the credit, resulting in a loss of business. Consequently, a company must maintain tight control over the credit granting process, so that just enough credit is issued to encourage business with a company's best customers, without going so far as to enhance sales by issuing excessive amounts of credit to customers with poor credit histories.

It is difficult to balance the pros and cons of granting credit, since granting an excessive amount of credit will tie up valuable working capital, while a restriction on credit will turn away potential sales. The balance between these two offsetting factors is usually influenced by the overall corporate strategy. For example, if there is a strong drive in the direction of increasing company profits, it is likely that management will clamp down on the amount of credit granted, since management does not want to incur any extra expense for bad debts. Alternatively, an aggressive management team that wants to increase revenues and market share will probably loosen the credit granting policy to bring in more sales, even though there is a greater risk of increasing the level of bad debt. In either case, the controller or treasurer will be on the receiving end of an order from top management regarding the level of credit to be granted. This is not an area in which middle management is given much say in the type of credit policy that a company will follow.

Within the strictures of a company's established credit policy, there are many steps that a controller can take to ensure that credit is granted in a reliable and consistent manner, and that the policy is strictly followed. The focus of a company's credit granting policy is in the areas of customer investigation, credit granting, and subsequent control:

- Investigate the customer. The easiest and most thorough source of information about a customer is the credit report. The premier issuer of this information is Dun & Brad-street, which provides phone or computer access to credit report information, so that a credit report can be in the requester's hands a minute after making the request. Other sources of information are trade references, though these tend to be biased in favor of the customer, since most customers will always be sure to make timely payments to their trade references. A limited amount of information can also be gleaned from a customer's bank, but this is rarely sufficient information on which to make a credit decision. There may also be detailed financial reports available from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) if a company is publicly held, but even this excellent source can be rendered invalid if a company is only dealing with a subsidiary of a publicly held company, since the financial results of the subsidiary will not be broken out in the financial reports.

- Grant credit. Once there is a sufficient amount of financial information about a customer, one must determine the amount of credit to give to the customer. This should be a consistent methodology; otherwise, there will be great variations in the amounts of credit granted to customers. Also, a wide range of credit amounts will make salespeople think that credit levels are highly negotiable, so they will attempt to sway the person granting credit to increase the amounts of credit given to their customers. The best approach is to come up with a formula that can be applied consistently to all customers. Though the exact method devised will vary by industry, a simple method is to use the median credit level granted by a customer's other suppliers, as noted in the credit report, and then reduce this amount by a standard percentage for every day that the customer is late in making payments to its other suppliers. For example, a customer who receives a median amount of $100,000 in credit from its suppliers, and who pays them ten days late, will receive a total credit amount of $50,000 if the controller decides to apply a 5 percent penalty to each day that a customer is late in making payments; this approach assumes that there is a direct correlation between a customer's ability to pay on time and the risk that the customer will default on its payments.

- Control subsequent credit transactions. The amount of credit granted will not matter if a company makes a habit of ignoring the established credit limit. This matter is discussed more fully in the Control over Accounts Receivable section later in this chapter; the key point is that there should be an automated check in the order entry system that automatically halts any new customer order that results in a level of credit that exceeds the preestablished limit that is already recorded in the system. If the level of automation is not sufficient to allow this method, a controller can authorize a continuing internal audit of credit levels to ensure that they are not being deliberately or inadvertently avoided by the order entry staff. Either approach ensures that credit levels, once established, will be maintained.

A key issue in the credit granting process is when the credit investigation is performed. If a company finds customers first and then asks the controller or treasurer to grant credit, it is common for the salespeople who worked hard to bring in the new customers to lobby equally hard on the customers' behalf to give them the largest possible amount of credit. This gives the salesperson the best chance of earning a large commission, which can come only from a large amount of sales volume. Granting credit after a sale is made makes the credit granting job an intense one, because there is great pressure from the sales staff to grant credit, which is especially difficult if the credit investigation reveals that a customer is a poor risk. A better approach is to implement some sales planning with the sales staff in advance, so that there is a target list of customers that the sales staff is asked to contact for orders. Using this approach, the controller can investigate potential customers in advance and advise the sales staff to avoid certain ones if their credit histories are poor. By using advance credit checks, a controller can avoid requests for excessive levels of credit by the sales staff.

While there is a need to grant credit to customers, one should note the pitfalls of extending too much credit. A methodical company will position credit investigations before new customer contacts, in order to avoid wasted efforts by the sales staff in contacting poor credit risks.

CUSTOMER MARGIN ANALYSIS

Although a formula can be used to grant credit to customers, there will be times when a customer or a salesperson calls to ask for more credit. If an excessive amount of credit is granted and then the customer defaults, the controller may have some explaining to do to a company officer or owner. However, there are some cases where a customer is so important to a company's survival that it is nearly mandatory to give the customer an inordinate amount of credit. How is a controller to make a judgment call regarding when to grant additional credit and when to turn it down?

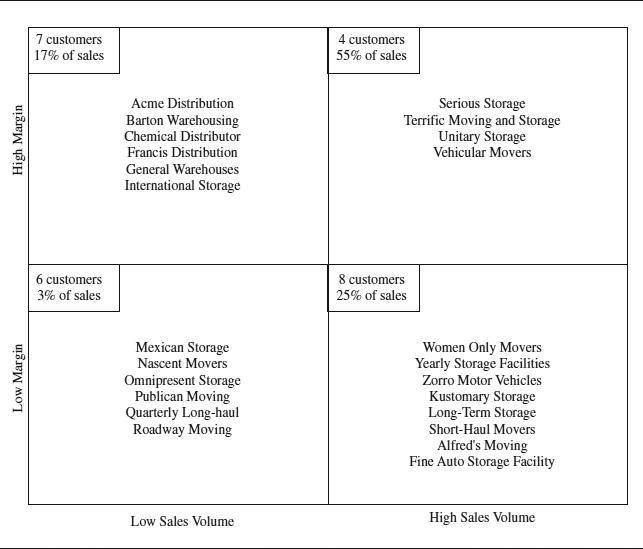

The answer is to use a customer margin analysis. As shown in Exhibit 9.1, a margin analysis is really a matrix that divides up customers into various categories based on the margins and volume that a company experiences with each one. Using the example, if a customer with both low margins and sales volume calls to demand an increase in credit, the controller's best response may be to chuckle warmly and hang up the phone—adding credit to a customer who yields minimal profits is simply making a bad situation worse. Alternatively, a request to increase credit for any customer with high margins should be looked at very seriously, since there will be a major increase in company profits if sales to this customer increase. Finally, credit to customers with low margins and high revenue volume may require scaling back to a lower level, since there is no reason to support sales volume on which there is no return. Thus, the credit granting decision should be strongly driven by the margins and sales volumes of each customer.

It is important to factor customer margins and sales volumes into the decision to grant credit; however, a controller should always keep in mind a customer's ability to pay down the credit—after all, making lots of money on a customer will not last if the high margins are offset by bad debts.

COLLECTIONS TASK

This section discusses a variety of ways to bring in accounts receivable as soon as possible, resulting in reduced working capital requirements and less risk of accounts becoming significantly overdue. The methods for enhancing collections fall into several categories. The first is collection techniques, which describes ways to bring in payments on existing debts. The second is altered payment methods, which looks at accelerating the speed with which payments travel from a customer to the accounting department. The final method is shrinking the entire billing and collection cycle, which focuses on ways to reduce the time needed to process orders, issue credit, generate invoices, and other matters. The methods are outlined in greater detail as:

EXHIBIT 9.1 CUSTOMER MARGIN MATRIX

- Collection techniques. This section covers several ways to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the collections staff in bringing in accounts receivable payments on time. The methods are:

- (a) Involve the sales staff. The people with the best customer contacts are the sales staff. They can frequently collect on accounts receivable that the collections staff cannot, because the salesperson can contact a different person within the customer's organization who can order an immediate payment that is otherwise frozen in the accounts payable area. This method is especially effective when the sales staff's commissions are tied to cash received, rather than sales, so that the sales personnel have a major interest in resolving any collection problems.

- (b) Create a relationship. It is much easier to collect money from someone you know. The best way to build up this kind of relationship is to take a few extra moments on the phone to chat with the customer's accounts payable person; by creating even such a minor relationship as this, the collections person has a much greater chance of obtaining money from the customer. The relationship can be enhanced by carefully avoiding any confrontations or heated discussions, actions which are common for an inexperienced collections person to make.

- (c) Follow overdue accounts closely. A customer who is deliberately delaying payments will be much more inclined to make payments to a company that is consistently persistent in calling about overdue accounts, since it is easier to pay these companies at the expense of other companies that are conveniently not calling to inquire about their accounts. It is especially effective to tell a customer when to expect a follow-up call, and then make that call on the predicted day, which reinforces in the customer's mind the perception that the collections person is not going away, and will continue to make inquiries until the debt is paid.

- (d) Use leverage. When there is no response from making a multitude of calls and other forms of contact with a customer regarding a payment, it is time to kick the issue upstairs to the controller, or even higher in the organization. When a customer's accounts payable person is not responding, it is quite possible that a different response can be obtained when the controller contacts his or her counterpart, since there may be a better relationship at that level. In some cases, though usually only for the largest debts, the two presidents may need to correspond. If none of these approaches work, a different kind of leverage may be necessary—cutting off service or shipments until payment is made. However, this approach must be used with care, since such a cutoff may have a drastic effect on customer relations.

- (e) Create a contact log. All of the previously cited collection methods can be made more effective by using a contact log. This is a simple device that lists the last date on which contact was made, and the next date on which action is required. A collections person can then flip through the log each day to see what actions are needed. It is helpful to include the most recent accounts receivable aging in the log, for easy reference when talking to customers.

- Altered payment methods. Besides jawboning customers to pay on time, it may be possible to alter the underlying method used to make payments, which can greatly reduce the time required to make collections. Any of the following approaches should be considered to alter the payment method.

- (a) Lockbox. This is a post office box that is opened in a company's name, but accessed and serviced by a remittance processor, which is normally a bank. By having a bank open mail containing checks and deposit these funds directly into a company's account, it is possible to reduce the time interval before the money would have been deposited by other means. In addition, lockboxes can be set up close to customers, so that there is a minimal mail float time. This also reduces the time before a company must wait to receive payment.

- (b) Wire transfer. This is a set of telegraphic messages between banks, usually through a Federal Reserve bank, whereby the sending bank instructs the Federal Reserve bank to charge the account of the sending bank and credit the account of the receiving bank.

- (c) Automated clearinghouse (ACH) transfer. This method allows banks to exchange electronic payments. Usually, the customer initiates a payment directly to the company's bank account.

- (d) Depository transfer check (DTC). Under this approach, a bank prepares a DTC on behalf of its customer against the customer's deposit account at another bank. It is a means for rapidly shifting funds from deposit accounts into concentration accounts from which investments can be made.

- (e) Preauthorized draft (PAD). This is a draft drawn by the company against the bank account of the customer. The method is most commonly used by insurance companies or other lenders where the payment is fixed and repetitive.

- Shrink the cycle. Besides altering collection methods and changing the type of customer payment, there are many other ways to shrink the cycle that begins with issuing an invoice to a customer and ends with the collection of cash. This last category is a catchall of ways to reduce the time required to complete the entire process. The shrinking methods are:

- (a) Accelerate billing frequency. If a company only issues invoices once a week, some billings will sit in a pile until the end of the week, when they could have been on their way to a customer much sooner. Daily invoicing should be the rule.

- (b) Alter payment terms. Sometimes a customer will radically alter its payment timing if there is a large enough early payment discount placed in front of them. Usually, a 2 percent discount for early payment is a sufficient enticement to bring in cash much earlier than was previously the case. However, such a large discount may have a major impact on profits if margins are already low, or if customers were already paying relatively quickly, so it should only be offered to those customers who are extremely late in paying. Although this approach may seem like a reward to those customers who are late in paying, it only reflects the realities of the collection situation.

- (c) Reduce billing errors. One of the most important reasons why customers do not pay is that they disagree with the information on a company invoice. Accordingly, it is imperative that a controller systematically track down errors (which are most easily revealed through the collections process, when customers tell the collections staff about invoicing errors) and fix them as soon as possible. A common mistake is sending an invoice to the wrong address or contact person, while others are to incorrectly price a product or to bill for the wrong product or service, either in type or quantity. There are usually a number of problems to be fixed before all errors are corrected. Even then, careful watch must be maintained over the invoicing process to ensure that errors are kept out.

- (d) Use electronic billings. Rather than sending a paper invoice, it is possible to use an electronic one, which has the advantage of avoiding the time required to move through the postal system. In addition, such a transmission can be automatically processed by a customer's computer system without ever being punched in again by a data entry clerk, so there are fewer chances of an error occurring on the customer's side when paying the invoice. An electronic billing is usually sent by electronic data interchange (EDI), which requires a considerable amount of advance preparation by a company and its customers to set up; because of the advance work required, it is generally best to only use this method with long-term customers with whom a company has a significant volume of business.

Although a major portion of collecting accounts receivable is contacting customers to request payment, a variety of other techniques have a major impact on the speed with which payments are collected. These techniques include using early payment discounts, electronic invoice delivery, and lockboxes. It takes a complete implementation of all these methods before a company will experience a significant decline in the amount of its outstanding accounts receivable.

MEASUREMENT OF ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

A controller may feel that, by making many collection improvements, the investment in accounts receivable is being reduced; however, it is impossible to be sure without using several performance measurements. Not all of the measures described in this section need to be implemented, but a controller should use a selection of them to gain a clear picture of the state of a company's accounts receivable. The measurements are:

- Accounts receivable turnover ratio. The simplest and one of the most effective ways to see if there are problems with accounts receivable is the turnover ratio. This measure illustrates how rapidly accounts receivable are being converted into cash. To calculate the measure, divide net sales by accounts receivable. For example, if the turnover ratio is 12, then accounts receivable are being collected after precisely one month. If turns are only six, then accounts receivable are going uncollected for two months, and so on. To gain a better idea of ongoing performance, it is best to track the turnover measure with a trend line.

- Days old when discount taken. When a customer takes a discount for early payment, it is understood that the payment will be made within the previously agreed-upon guidelines, such as taking a discount only if payment is made within a certain number of days. This measure is designed to spot those customers who take the discount, but who stretch the payment out beyond the standard number of terms. To calculate the measure, one must write a program for the accounting software that lists the date of each invoice paid and the date when cash was applied against the invoice. The difference between these two dates, especially when grouped by customer, will be a good indicator of any ongoing problems with late payments on discount deals.

- Days' sales outstanding. A common measure that may be swapped with the accounts receivable turnover measure is days' sales outstanding (DSO). This measure converts the amount of open accounts receivable to a figure that shows the average number of days that accounts are going unpaid. The measure is used somewhat more frequently than turnover, since the number of days outstanding is considered to be somewhat more understandable. To measure it, divide the average accounts receivable by annual credit sales, and multiply by 365. To determine if DSO is reasonable, compare it to the standard payment terms. For example, a DSO of 40 is good if standard terms are 30 days to pay, whereas it is poor if standard terms are only 10 days. If collections are well managed, the DSO should be no more than one third beyond the terms of sale. For a more precise view of the collection operations, the DSO can be calculated for each customer.

- Percent of bad debt losses. It is necessary to track the proportion of sales that are written off as bad debts, because a high percentage is a strong indicator of either lax collection practices or an excessively lenient credit granting policy. To calculate the measure, divide the bad debt amount for the month by credit sales. An alternative measure may be to divide the bad debt by sales from several months ago, on the theory that the bad debts were more specifically related to sales in a previous time period.

- Percent of unexplained credits taken. Some customers take credits on a whim, resulting in considerable write-offs for which there is no explanation. If this comes to a reasonable percentage of sales to a customer, that customer should be terminated, since it is cutting into company margins. Researching the credits also requires a large proportion of accounting staff time. To calculate the measure, track all invoices that are not completely paid and divide by sales to customers; this measure should be completed on a customer-by-customer basis to gain a better understanding of which customers are causing the problem.

- Reasons for bad debt write-offs. A less common measure is to manually accumulate the reasons why sales are written off as bad debts, and to summarize total bad debts by these explanations. One can then sort the reasons by declining dollar volume to see what problems are arising most frequently, which can lead to steps to fix various credit granting or collection problems. It is also worthwhile to accumulate bad debt information by customer, to see which ones are responsible for the largest number of write-offs.

The measurements discussed in this section are useful for determining how rapidly accounts receivable are collected, as well as the size of and reasons for bad debts. Properly tracking these measures results in a fine management tool for altering the methods used to collect accounts receivable, as well as the credit granting policy, resulting in faster receivable turnover and fewer bad debt losses.

CONTROL OVER ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

This chapter is primarily concerned with the processes needed to grant credit and then collect it. However, an astute controller must be sure that these processes are operational, or else incorrect credit levels will be granted, and collections will not occur as expected. Proper controls are required to ensure that processes function as planned. This section discusses the key controls that one should install to make sure that the accounts receivable function produces results that are within expectations.

This section is divided into two parts: controls over the credit granting process, and controls over collections. The first part, credit granting, involves controls over the timing of credit processing, ongoing customer monitoring, excess credit, and process reviews:

- Control the timing of granting credit. One of the largest problems with granting credit is that it is always a rush—a salesperson runs in with a new customer order and demands an immediate credit check, so that the order can be accepted and the salesperson can earn a commission. Unfortunately, the compressed time period forces a controller to dispense with an appropriate number of credit checks, and may even result in granting credit with no review work at all. A good control over this process is to enforce the early identification of sales prospects and the communication of this information to the accounting or treasury departments, so that a thorough credit review can be completed prior to the conclusion of a sale.

- Monitor the financial condition of customers. A customer may suffer financial reverses and suddenly be unable to pay its bills. To avoid being caught with a large amount of outstanding credit in such situations, there should be a control that requires the credit granting staff to annually review the financial condition of all customers with significant credit lines; this information can come from either the customers or a credit reporting agency. Unfortunately, some companies suffer financial reverses that are so sudden that an annual financial review will not catch the decline; for these situations, there should be an additional control requiring financial reviews for any customer who suddenly begins to stretch out payment dates on open invoices. This control results in rapid action to shrink credit balances where customers are clearly unable to pay.

- Review excess credit taken. Some accounting systems allow customers to exceed the credit limits programmed into the accounting database. In such situations, the official credit level is essentially meaningless, since it is not observed. To avoid this problem, the controller should create and review a report that lists all customers who have exceeded their preset credit limits. A controller can then use this report to follow up with the order entry department to ensure that, in the future, credit limits are examined prior to accepting additional orders from customers.

- Review the process. Many credit granting processes are excessively cumbersome, for a variety of reasons: They involve too many people, require input from too many sources, and need multiple approvals. The result is a long time period before credit levels are set, as well as too much cost invested in the process. To avoid this problem, there should be a periodic review, preferably by the internal auditing staff, that flowcharts the entire credit granting process, makes recommendations to reduce its cost and cycle time, and which follows up to verify that recommendations have been implemented. An annual review of this type will ensure that the process is lean, as well as responsive to the needs of customers and other departments.

Once there are a sufficient number of controls over the credit granting process, one must still be concerned with a company's ability to collect on credit that has been issued to customers. The controls that assist in this task include using the services of other departments, reviewing cycle time, and watching over bad debt approvals. The controls are:

- Enroll other departments in the effort. The accounting staff cannot be completely successful in collecting money from customers unless it uses the efforts of other departments. A good control over this issue is to have the internal audit staff check on the collection team's efforts to use other departments prior to writing off accounts receivable. For example, there should be an effort to capitalize on the services of the sales staff to collect from their customers (which can be made easier if the sales staff's commissions are only paid when payment is received from customers), or to use other personal relationships, such as between the presidents of the company and the customer, to pay off a debt.

- Look for special payment deals. Sometimes, it is difficult to collect payment on an invoice, not because the collections staff is doing a poor job, but because the sales staff agreed to a special payment deal with the customer. Though it is occasionally necessary to agree to special deals, sometimes they happen without proper approvals from management. To detect such deals, there should be an occasional confirmation process with customers, whereby the customers are asked to confirm the payment terms of their invoices. Any disparity between the company's payment terms and those recorded by the customer should be investigated.

- Match invoices to the shipping log. Collection problems can arise when there are incorrect billings, such as when an invoice lists the wrong quantity of a shipped product. To maintain control over this issue, one can conduct a periodic comparison of the quantities noted on invoices to the quantities actually shipped, as noted in the shipping log. Since the amount billed is usually taken from a copy of the bill of lading (BOL), the BOL can also be compared to the bill and the shipping log to see where record inaccuracies are occurring.

- Remove other accounts receivable for the receivable account. It is difficult to gain a true understanding of the amount of overdue accounts receivable if the accounts receivable balance is skewed by the presence of miscellaneous items, such as amounts owed from company officers or taxing authorities. It is best to strip these accounts out of any receivable turnover calculation, thereby arriving at a “pure” turnover figure that will reveal the need for additional collection activities.

- Report on collection actions taken. It is difficult to collect an account receivable unless there is a history of the efforts previously taken to bring in a payment. Such a record should include the name of the person contacted, the date when this happened, and the nature of the discussion. A good control here is to conduct a periodic review of the contact data for all overdue accounts receivable, and to require better recordkeeping where appropriate.

- Report on receivable items by customer. The accounts receivable aging report is the single best control over the collections process, because it clearly shows any invoices that are overdue for payment. The report is sorted by invoice for each customer, and lists invoice amounts by category—current, 30 to 60 days old, 61 to 90 days old, and over 90 days old. By reviewing the totals for each customer, it is an easy matter to determine where the problem accounts and invoices are located, and where additional collection actions are needed.

- Review billing frequency. One problem with collections is the time needed to issue an invoice to the customer. A lazy billing person may wait several days or even a week between issuing invoices, which can seriously delay the time before customers will return payments for them. To detect this problem, there should be a continuing audit of the billing process that compares the date on which invoices were created to the date when products actually shipped. Any large disparity between these two dates should be investigated.

- Review credits taken. A common problem is that someone in the accounting department “cleans up” the accounts receivable aging by processing a number of credits that write off old accounts. This practice is fine if there is a proper approval process for the credits, but is otherwise only a lazy way to get rid of old accounts without any real effort to collect them. The best way to control this practice is to conduct a periodic review of all credits taken, and to verify that each one was approved by an authorized manager. To save time, it may make sense to allow credits on small balances without any associated approval.

- Segregate the accounts receivable and cash receipts functions. When the person who collects cash and applies it to accounts receivable records is the same one who creates invoices, there may be a temptation to keep some of the cash and alter the receivable records with false credits to hide the missing money. The best way to control this potential problem is to split the two functions among different people, so that the problem can only arise if there is collusion between multiple personnel, which is a much less likely occurrence.

- Verify pricing. Customers may not want to pay for invoices if the per-unit prices charged to them are incorrect. To control this problem, it is useful to occasionally compare the prices listed on invoices to the official company price list. Any pricing problems require immediate follow-up, as well as rebilling customers if the prices charged to them were incorrect.

There were many controls that can be installed to ensure that the credit granting and collection tasks operate as planned. This is an area in which the best intentions for setting up a quality system are not good enough. There must also be a set of firmly enforced controls that are regularly reviewed and enforced, so that credit is granted only after a reasonable amount of review and collection efforts are made in a timely manner, resulting in the minimal amount of bad debt.

BUDGETING FOR ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE BALANCES

The planning function of the controller as related to accounts receivable largely has to do with the preparation of the annual business plan, and perhaps plans for a shorter time span. Working closely with the treasurer and/or credit manager, the controller's responsibilities include:

- Determining, within suitable interim time periods, the amount to be invested in accounts receivable for the planning horizon—the accounts receivable budget. Typically this is the month-end balance for each month of annual plan.

- Testing the receivable balances to determine that the planned turnover rate or daily investment is acceptable or within the standard.

- Based on past experience, or other criteria, estimating the amount required for a reasonable reserve for doubtful accounts.

- Consolidating the accounts receivable budget with other related budgets to determine that the entity has adequate funds to meet the needed receivables investment.

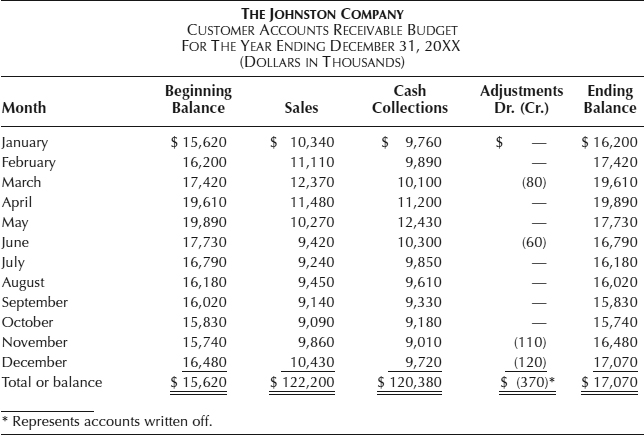

The determination of the monthly investment in accounts receivable would produce a plan for the next business year substantially similar to that shown in Exhibit 9.2.

Additions to the monthly customer accounts receivable balance would be based on the sales plan. Collections would be determined as described in the preceding chapter on cash planning. Essentially the same “entries” would be made using the estimated data as are made for the actual monthly activity. The same process used in calculating the receivables balance for the annual plan may be used for the long-range plan, although only annual (not monthly) estimates need be used. Computer software programs are available to determine the receivable balance and to age the accounts.

While the illustration reflects the customer accounts receivable activity, a comparable procedure would be used to estimate the “other miscellaneous receivable” balances for such typically small transactions as:

- Amounts due from officers and employees

- Claims receivable

- Accounts receivable—special transactions

- Notes receivable—miscellaneous

EXHIBIT 9.2 PLANNED INVESTMENT IN ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLES