13

MANAGEMENT OF SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY

INTRODUCTION

Shareholders' equity is the interest of the shareholders, or owners, in the assets of a company, and at any time is the cumulative net result of past transactions affecting this segment of the balance sheet. This equity is created initially by the owner's investment in the entity, and may be increased from time to time by additional investments, as well as by net earnings. It is reduced by distributions of the equity to the owners (usually as dividends). Further, it may also decrease if the enterprise is unprofitable. When all liabilities are satisfied, the balance—the residual—belongs to the owners.

Basic accounting concepts govern the accounting for shareholders' equity as a whole, for each class of shareholder, and for the various segments of the equity interest, such as capital stock, contributed capital, or earned capital. This chapter does not deal with the accounting niceties regarding the ownership interest. It is assumed the controller is well grounded in such proper treatment, or will become so. The concerns relate to the shareholders' interest as a total and not any special accounting segments.

IMPORTANCE OF SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY

As previously stated, capital structure is composed of all long-term obligations and shareholders' equity—in a sense, the “permanent” capital. Some would describe the capital structure of the enterprise as the cornerstone of financial policy. Such policy must be so planned that it will command respect from investors far into the future. But of the two basic elements, it is the shareholders' equity that is critical. This equity must provide a margin of safety to protect the senior obligations. Stated another way, in most instances, without the shareholders' equity, no senior obligations could be issued. It is for this reason, among others, that proper management of the equity is of paramount importance. In a sense, the controller, together with other members of financial management, must safeguard the long-term financial interests of not only the shareholders but also the providers of long-term credit, to say nothing of the sources of short-term capital such as commercial banks and suppliers. This is accomplished, in part, by properly planning and controlling the equity base of the enterprise.

ROLE OF THE CONTROLLER

Given the importance of shareholders' equity and the need to manage it prudently, what should be the role of the controller? In a general sense, as one of the principal financial officers of the corporation, the controller must properly account for the shareholders' equity, providing those analyses and recommending those actions that are consistent with enhancing shareholder value over the long term. The task would require attention to these specific actions:

- Properly accounting for the shareholders' equity in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). This includes the historical analysis of the source of the equity and the segregation of the cumulative equity by class of shareholder.

- Preparing the appropriate reports on the status and changes in shareholders' equity as required by agencies of the U.S. government (e.g., Securities and Exchange Commission), by management, and by credit agreements and other contracts.

- Making the necessary analyses to assist in planning the most appropriate source (debt or shareholders' equity) of new funds, and the timing and amount required of each.

- As appropriate, maintaining in proper and economical form the capital stock records of the individual shareholders, with the related meaningful analysis (by nature of owner—individual, institution, and so forth—by geographic area, by size of holding, etc.) or assuring that it is done. (In larger firms, a separate department or an outside service might perform these functions.)

- Periodically making the required analysis, reporting on, and making recommendations or observations on such matters as:

- Dividend policy

- Dividend reinvestment plans

- Stock splits or dividends

- Stock repurchase

- Capital structure

- Trend and outlook for earnings per share

- Cost of capital for the company and industry

- Tax legislation as it affects shareholders

- Price action of the market price of the stock, and influences on it

Plainly, there is a grassland of financial subjects on which the controller can graze and in due course make useful suggestions.

Before a discussion of specifics about the planning phases regarding shareholders' equity, some interesting relationships should be understood:

- Rate of growth in equity as related to the return on equity (ROE)

- Growth in earnings per share as related to ROE

- Cost of capital

- Dividend payout ratio

- Relationship of long-term debt to equity

GROWTH OF EQUITY AS A SOURCE OF CAPITAL

As a company grows, it usually requires additional funds to finance working capital and plant and equipment, as well as for other purposes. Of course, it could issue additional shares of stock, but this might dilute earnings per share for a time or perhaps raise questions of control. Another alternative is to borrow long-term funds. Some managements may wish to do neither. As a result, the remaining source of long-term capital (excluding some assets sales, etc.) is the growth in retained earnings. But such a method is typically a slow way to gain additional capital. The rate of growth of equity is germane to establishing target rates of return on equity, selecting sources of capital, and monitoring dividend policy.

The annual growth in shareholders' equity from internal sources may be defined as the rate of return earned on such equity multiplied by the percentage of the earnings retained. It may be represented by this formula:

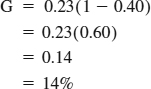

As an example, if a company can earn about 23% each year on its equity, and the payout ratio is 40%, then shareholders' equity will grow at 14% per year, calculated as:

Under these circumstances, if the management thinks the company can grow in sales and earnings at about 30% per year, if additional funds will be needed at about this same rate, and if the dividend payout is to remain at 40%, then management will require some outside capital for the growth potential to be realized.

RETURN ON EQUITY AS RELATED TO GROWTH IN EARNINGS PER SHARE

Another facet of the shareholders' equity role is the relationship of the ROE to the rate of annual increase in earnings per share (EPS). This connection is often not understood even by some financial executives. Basically, the rate of return on shareholders' equity, when adjusted for the payout ratio, produces the rate of growth per year in EPS. It may be expressed in this formula:

Growth per year in EPS = ROE × retention ratio

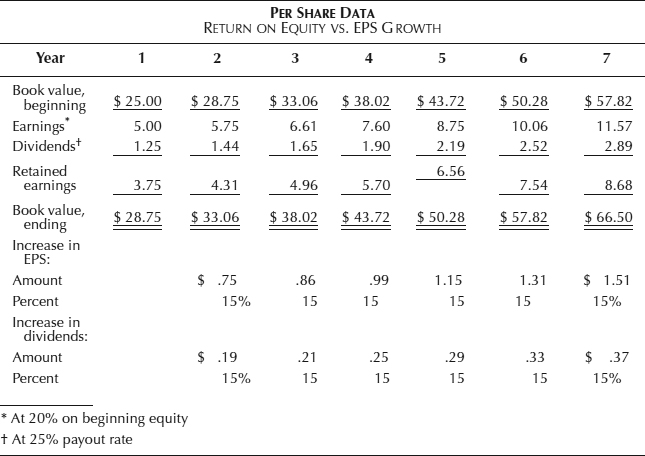

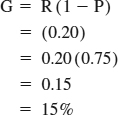

This relationship is illustrated in Exhibit 13.1. Thus, assuming a constant return on equity of 20% and a constant dividend payout ratio of 25%, the EPS growth rate is calculated by means of the same formula as for the growth of shareholders' equity:

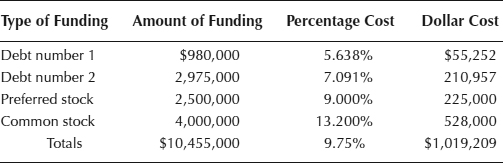

For illustrative purposes to management or the board of directors, these same factors can be translated into book value per share, earnings per share, and dividends per share, as shown in Exhibit 13.2. In such terms, explanations about the shareholders' interest often are more easily understood. It is to be noted in Exhibit 13.2 that, with a constant dividend payout ratio, the annual dividend rate of increase is the same as the annual growth rate in EPS.

EXHIBIT 13.1 CONSTANT RETURN ON EQUITY VERSUS EPS GROWTH

GROWTH IN EARNINGS PER SHARE

Prudent financial planning will consider the impact of decisions on EPS. Management is concerned with the growth in EPS since one of its tasks is to enhance shareholder value. And continual increases in EPS each year will raise shareholder value through its recognition in a higher P/E ratio and usually a rising dividend payment. Moreover, the growth in EPS is one of the measures of management as viewed by the financial community, including financial analysts.

Given the importance of EPS, financial officers should bear in mind that the EPS will increase as a result of any one of these actions:

- The plow-back of some share of earnings, even as long as the rate of return on equity remains just constant—as illustrated by the calculations in Exhibits 13.1 through 13.2. (A growth in EPS does not necessarily mean that the management is achieving a higher rate of return on equity.)

- An actual increase in the rate of return earned on shareholders' equity

- Repurchase of common shares as long as the rate of return on equity does not decrease

- Use of prudent borrowing—financial leverage (see Chapter 12)

- Acquisition of a company whose stock is selling at a lower P/E than the acquiring company

- Sale of shares of common stock above the book value of existing shares, assuming the ROE is maintained

Financial planning should keep all the alternatives in mind. But of all these actions, the one most likely sustainable and translatable into a healthy growth in EPS is a constant, or increasing, return on shareholders' equity.

EXHIBIT 13.2 PER SHARE—ROE VS. GROWTH RATE

COST OF CAPITAL

Investors are willing to place funds at risk in the expectation of recovering such capital and making a reasonable return. Some individuals or companies might prefer to invest in a practically risk-free security, such as U.S. government bonds; others will assume greater risks but expect a correspondingly higher rate of return. Cost of capital, then, may be defined as the rate of return that must be paid to investors to induce them to supply the necessary funds (through the particular instrument under discussion). Thus, the cost of a bond would be represented by the interest payments plus the recovery of the bond purchase price, perhaps plus some capital gains. The cost of common shares issued would be represented by the dividend paid plus the appreciation of the stock. Capital will flow to those markets where investors expect to receive a rate of return consistent with their assessment of the financial and other risks, and a rate that is competitive with alternative investments.

Knowledge of the cost of capital is important for two reasons:

- The financial manager must know what the cost of capital is and offer securities that provide a competitive rate, in order to be able to attract the required funds to the business.

- In making investment decisions, such as for plant and equipment, the financial manager must secure a return that is, on average, at least as high as the cost of capital. Otherwise, there is no reason to make an investment that yields only the cost or less. The manager is expected to gain something for the shareholder. Hence, the cost of capital theoretically sets the floor as the minimum rate of return before any investment should even be considered.

Prudent management of the shareholders' equity, then, involves:

- Attempting to finance the company so as to achieve the optimum capital structure, and, hence, a reasonable cost of capital

- Properly determining the cost of capital, and employing such knowledge in relevant investment decisions

COMPONENTS OF COST OF CAPITAL1

Before determining the amount of a company's cost of capital, it is necessary to determine its components. The following two sections describe in detail how to arrive at the cost of capital for these components. The weighted average calculation that brings together all the elements of the cost of capital is then described in the “Calculating the Weighted Cost of Capital” Section.

The first component of the cost of capital is debt. This is a company's commitment to return to a lender both the interest and principal on an initial or series of payments to the company by the lender. This can be short-term debt, which is typically paid back in full within one year, or long-term debt, which can be repaid over many years, with either continual principal repayments, large repayments at set intervals, or a large payment when the entire debt is due, which is called a balloon payment. All these forms of repayment can be combined in an infinite number of ways to arrive at a repayment plan that is uniquely structured to fit the needs of the individual corporation.

The second component of the cost of capital is preferred stock. This is a form of equity that is issued to stockholders and that carries a specific interest rate. The company is obligated to pay only the stated interest rate to shareholders at stated intervals, but not the initial payment of funds to the company, which it may keep in perpetuity, unless it chooses to buy back the stock. There may also be conversion options, so that a shareholder can convert the preferred stock to common stock in some predetermined proportion. This type of stock is attractive to those companies that do not want to dilute earnings per share with additional common stock, and that also do not want to incur the burden of principal repayments. Though there is an obligation to pay shareholders the stated interest rate, it is usually possible to delay payment if the funds are not available, though the interest will accumulate and must be paid when cash is available.

The third and final component of the cost of capital is common stock. A company is not required to pay anything to its shareholders in exchange for the stock, which makes this the least risky form of funding available. Instead, shareholders rely on a combination of dividend payments, as authorized by the Board of Directors (and which are entirely at the option of the Board – authorization is not required by law), and appreciation in the value of the shares. However, since shareholders indirectly control the corporation through the Board of Directors, actions by management that depress the stock price or lead to a reduction in the dividend payment can lead to the firing of management by the Board of Directors. Also, since shareholders typically expect a high return on investment in exchange for their money, the actual cost of these funds is the highest of all the components of the cost of capital.

As will be discussed in the next two sections, the least expensive of the three forms of funding is debt, followed by preferred stock and common stock. The main reason for the differences between the costs of the three components is the impact of taxes on various kinds of interest payments. This is of particular concern when discussing debt, which is covered in the next section.

CALCULATING THE COST OF DEBT

This section covers the main factors to consider when calculating the cost of debt, and also notes how these factors must be incorporated into the final cost calculation. We also note how the net result of these calculations is a form of funding that is less expensive than the cost of equity, which is covered in the next section.

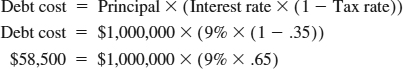

When calculating the cost of debt, it is important to remember that the interest expense is tax deductible. This means that the tax paid by the company is reduced by the tax rate multiplied by the interest expense. An example is shown in Exhibit 13.3, where we assume that $1,000,000 of debt has a basic interest rate of 9.5 percent, and the corporate tax rate is 35 percent.

The example clearly shows that the impact of taxes on the cost of debt significantly reduces the overall debt cost, thereby making this a most desirable form of funding.

EXHIBIT 13.3 CALCULATING THE INTEREST COST OF DEBT, NET OF TAXES

If a company is not currently turning a profit, and therefore not in a position to pay taxes, one may question whether or not the company should factor the impact of taxes into the interest calculation. The answer is still yes, because any net loss will carry forward to the next reporting period, when the company can offset future earnings against the accumulated loss to avoid paying taxes at that time. Thus, the reduction in interest costs caused by the tax deductibility of interest is still applicable even if a company is not currently in a position to pay income taxes.

Another issue is the cost of acquiring debt, and how this cost should be factored into the overall cost of debt calculation. When obtaining debt, either through a private placement or simply through a local bank, there are usually extra fees involved, which may include placement or brokerage fees, documentation fees, or the price of a bank audit. In the case of a private placement, the company may set a fixed percentage interest payment on the debt, but find that prospective borrowers will not purchase the debt instruments unless they can do so at a discount, thereby effectively increasing the interest rate they will earn on the debt. In both cases, the company is receiving less cash than initially expected, but must still pay out the same amount of interest expense. In effect, this raises the cost of the debt. To carry forward the example in Exhibits 13.3 through 13.4, we assume that the interest payments are the same, but that brokerage fees were $25,000 and that the debt was sold at a 2% discount. The result is an increase in the actual interest rate.

When compared to the cost of equity that is discussed in the following section, it becomes apparent that debt is a much less expensive form of funding than equity. However, though it may be tempting to alter a company's capital structure to increase the proportion of debt, thereby reducing the overall cost of capital, there is a significant risk of being unable to make debt payments in the event of a reduction in cash flow, possibly resulting in bankruptcy.

CALCULATING THE COST OF EQUITY

This section shows how to calculate the cost of the two main forms of equity, which are preferred stock and common stock. These calculations, as well as those from the preceding section on the cost of debt, are then combined in the following section to determine the weighted cost of capital.

EXHIBIT 13.4 CALCULATING THE INTEREST COST OF DEBT, NET OF TAXES, FEES, AND DISCOUNTS.

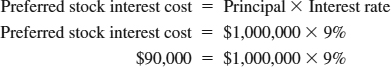

Preferred stock stands at a midway point between debt and common stock. It requires an interest payment to the holder of each share of preferred stock, but does not require repayment to the shareholder of the amount paid for each share. There are a few special cases where the terms underlying the issuance of a particular set of preferred shares will require an additional payment to shareholders if company earnings exceed a specified level, but this is a rare situation. Also, some preferred shares carry provisions that allow delayed interest payments to be cumulative, so that they must all be paid before dividends can be paid out to holders of common stock. The main feature shared by all kinds of preferred stock is that, under the tax laws, interest payments are treated as dividends instead of interest expense, which means that these payments are not tax deductible. This is a key issue, for it greatly increases the cost of funds for any company using this funding source. By way of comparison, if a company has a choice between issuing debt or preferred stock at the same rate, the difference in cost will be the tax savings on the debt. In the following example, a company issues $1,000,000 of debt and $1,000,000 of preferred stock, both at 9% interest rates, with an assumed 35% tax rate.

If the same information is used to calculate the cost of payments using preferred stock, we have the following result:

The above example shows that the differential caused by the applicability of taxes to debt payments makes preferred stock a much more expensive alternative. This being the case, why does anyone use preferred stock? The main reason is that there is no requirement to repay the stockholder for the initial investment, whereas debt requires either a periodic or balloon payment of principal to eventually pay back the original amount. Companies can also eliminate the preferred stock interest payments if they include a convertibility feature into the stock agreement that allows for a conversion to common stock at some preset price point for the common stock. Thus, in cases where a company does not want to repay principal any time soon, but does not want to increase the amount of common shares outstanding, preferred stock provides a convenient, though expensive, alternative.

The most difficult cost of funding to calculate by far is common stock, because there is no preset payment from which to derive a cost. Instead, it appears to be free money, since investors hand over cash without any predetermined payment or even any expectation of having the company eventually pay them back for the stock. Unfortunately, the opposite is the case. Since holders of common stock have the most at risk (they are the last ones paid off in the event of bankruptcy), they are the ones who want the most in return. Any management team that ignores holders of its common stock and does nothing to give them a return on their investments will find that these people will either vote in a new board of directors that will find a new management team, or else they will sell off their shares at a loss to new investors, thereby driving down the value of the stock and opening up the company to the attentions of a corporate raider who will also remove the management team.

One way to determine the cost of common stock is to make a guess at the amount of future dividend payments to stockholders, and discount this stream of payments back into a net present value. The problem with this approach is that the amount of dividends paid out is problematic, since they are declared at the discretion of the board of directors. Also, there is no provision in this calculation for changes in the underlying value of the stock; for some companies that do not pay any dividends, this is the only way in which a stockholder will be compensated.

A better method is called the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). Without going into the very considerable theoretical detail behind this system, it essentially derives the cost of capital by determining the relative risk of holding the stock of a specific company as compared to a mix of all stocks in the market. This risk is composed of three elements. The first is the return that any investor can expect from a risk-free investment, which is usually defined as the return on a U.S. government security. The second element is the return from a set of securities considered to have an average level of risk. This can be the average return on a large “market basket” of stocks, such as the Standard & Poor's 500, the Dow Jones Industrials, or some other large cluster of stocks. The final element is a company's beta, which defines the amount by which a specific stock's returns vary from the returns of stocks with an average risk level. This information is provided by several of the major investment services, such as Value Line. A beta of 1.0 means that a specific stock is exactly as risky as the average stock, while a beta of 0.8 would represent a lower level of risk and a beta of 1.4 would be higher. When combined, this information yields the baseline return to be expected on any investment (the risk-free return), plus an added return that is based on the level of risk that an investor is assuming by purchasing a specific stock. This methodology is totally based on the assumption that the level of risk equates directly to the level of return, which a vast amount of additional research has determined to be a reasonably accurate way to determine the cost of equity capital. The main problem with this approach is that a company's beta will vary over time, since it may add or subtract subsidiaries that are more or less risky, resulting in an altered degree of risk. Because of the likelihood of change, one must regularly recompute the equity cost of capital to determine the most recent cost.

The calculation of the equity cost of capital using the CAPM methodology is relatively simple, once one has accumulated all the components of the equation. For example, if the risk-free cost of capital is 5%, the return on the Dow Jones Industrials is 12%, and ABC Company's beta is 1.5, the cost of equity for ABC Company would be:

Cost of equity capital = Risk-free return + Beta( Average stock return − Risk-free return)

Cost of equity capital = 5% + 1.5 ( 12% − 5%)

Cost of equity capital = 5% + 1.5 × 7%

Cost of equity capital = 5% + 10.5%

Cost of equity capital = 15.5%

Though the example uses a rather high beta that increases the cost of the stock, it is evident that, far from being an inexpensive form of funding, common stock is actually the most expensive, given the size of returns that investors demand in exchange for putting their money at risk with a company. Accordingly, this form of funding should be used the most sparingly in order to keep the cost of capital at a lower level.

CALCULATING THE WEIGHTED COST OF CAPITAL

Now that we have derived the costs of debt, preferred stock, and common stock, it is time to assemble all three costs into a weighted cost of capital. This section is structured in an example format, showing the method by which the weighted cost of capital of the Canary Corporation is calculated. Following that, there is a short discussion of how the cost of capital can be used.

The chief financial officer of the Canary Corporation, Mr. Birdsong, is interested in determining the company's weighted cost of capital, to be used to ensure that projects have a sufficient return on investment, which will keep the company from going to seed. There are two debt offerings on the books. The first is $1,000,000 that was sold below par value, which garnered $980,000 in cash proceeds. The company must pay interest of 8.5% on this debt. The second is for $3,000,000 and was sold at par, but included legal fees of $25,000. The interest rate on this debt is 10%. There is also $2,500,000 of preferred stock on the books, which requires annual interest (or dividend) payments amounting to 9% of the amount contributed to the company by investors. Finally, there is $4,000,000 of common stock on the books. The risk-free rate of interest, as defined by the return on current U.S. government securities, is 6%, while the return expected from a typical market basket of related stocks is 12%. The company's beta is 1.2, and it currently pays income taxes at a marginal rate of 35%. What is the Canary Company's weighted cost of capital?

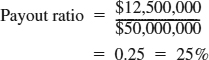

The method we will use is to separately compile the percentage cost of each form of funding, and then calculate the weighted cost of capital, based on the amount of funding and percentage cost of each of the above forms of funding. We begin with the first debt item, which was $1,000,000 of debt that was sold for $20,000 less than par value, at 8.5% debt. The marginal income tax rate is 35%. The calculation is as follows.

We employ the same method for the second debt instrument, for which there is $3,000,000 of debt that was sold at par; $25,000 in legal fees were incurred to place the debt, which pays 10% interest. The marginal income tax rate remains at 35%. The calculation is as follows:

Having completed the interest expense for the two debt offerings, we move on to the cost of the preferred stock. As noted above, there is $2,500,000 of preferred stock on the books, with an interest rate of 9%. The marginal corporate income tax does not apply, since the interest payments are treated like dividends, and are not deductible. The calculation is the simplest of all, for the answer is 9%, since there is no income tax to confuse the issue.

To arrive at the cost of equity capital, we take from the example a return on risk-free securities of 6%, a return of 12% that is expected from a typical market basket of related stocks, and a beta of 1.2. We then plug this information into the following formula to arrive at the cost of equity capital:

Cost of equity capital = Risk-free return + Beta(Average stock return − Risk-free return)

Cost of equity capital = 6% + 1.2(12% − 6%)

Cost of equity capital = 13.2%

Now that we know the cost of each type of funding, we can construct a table such as the one shown in Exhibit 13.5 that lists the amount of each type of funding and its related cost, which we can quickly sum to arrive at a weighted cost of capital.

When combined into the weighted average calculation shown in Exhibit 13.5, we see that the weighted cost of capital is 9.75%. Though there is some considerably less expensive debt on the books, the majority of the funding is comprised of more expensive common and preferred stock, which drives up the overall cost of capital.

DIVIDEND POLICY

Dividend policy is a factor to be considered in the management of shareholders' equity in that:

- Cash dividends paid are the largest recurring charge against retained earnings for most U.S. corporations.

- The amount of dividends paid, which reduces the amount of equity remaining, will have an impact on the amount of long-term debt that can be prudently issued in view of the long-term debt to equity ratio that usually governs financing.

- Dividend payout is an influence on the reception of new stock issues.

- Dividend policy is an element in most loan and credit agreements—with restrictions on how much may be paid.

To Pay or Not to Pay Cash Dividends?

If a company has discontinued cash dividends, for whatever reason, or if a corporation has never paid a cash dividend, then most readers would appreciate the desirability of discussing whether cash dividends should be paid. However, even if cash dividends are now being disbursed, the question should be considered.

Some companies do not pay cash dividends on the basis that they can earn a higher rate of return on reinvested earnings than can a shareholder by directly investing in new purchases of stock. This may or may not be true. It should be recognized that one purpose of sound financial management is to maximize the return to the shareholder over the longer period. Therefore, this is the criterion: In the company involved, will it serve to increase the long-term return to the shareholder by paying a dividend? This question is asked in the context that the return to the common shareholder consists of two parts: (1) the dividend and (2) the appreciation in the price of the security. The financial management of the firm should consider the type of investor attracted to the stock and the expectation of the investors. The examination of the actions of other companies and the opinion of knowledgeable investment bankers may be helpful. In general, the ability to invest all the earnings at an acceptable rate of return is not a convincing reason to pay no dividend. After all, a dividend is here and now, and future growth is more problematical. Probably, other than in the case of a highly speculative situation or a company in severe financial difficulty, some case dividend should be paid. This decision, however, is judgmental.

EXHIBIT 13.5 WEIGHTED COST OF CAPITAL CALCULATION

Dividend payments are determined by a number of influences, including:

- The need for additional capital for expansion or other reasons

- Cash flow of the enterprise

- Industry practice

- Shareholders' expectations

The amount to be paid may be calculated in one of two ways: (1) by the dividend payout ratio or (2) as a percentage of beginning net worth each year.

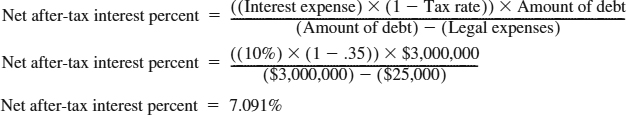

The most common practice is to measure dividends as a percentage of earnings. This payout ratio is determined as:

![]()

In this example, the payout ratio of 25% is calculated in this fashion:

Another way of calculating dividends, although less common than the payout method, is as a percentage of beginning net worth (book value attributable to common shares). The procedure is:

It has been suggested that a primary profit goal of an enterprise should be a specified rate of return on shareholders' equity. If this is accepted as a primary planning tool, then there is a certain logic that could justify using this same base (shareholders' equity) for the calculation of dividend payments—at least for internal planning purposes. Moreover, because earnings do fluctuate, there is an added stabilizing influence if dividends are based on book value. Also, as long as shareholders' equity is increasing and dividends are a constant rate of beginning net worth, then dividends would increase, the dividend payout ratio would drop, and the retention share of earnings would increase.

Dividend payment practices send a message to the financial community, and investors and analysts accept the pattern as an indication of future payments. Hence, when a dividend payment rate is set, a dividend reduction should be avoided if at all possible.

Dividend payment patterns may follow any one of several, such as:

- A constant or regular quarterly payment

- A constant pattern with regularly recurring increases—perhaps the same quarter each year

- A constant pattern with irregular increases

- A constant pattern with period extras so as to avoid committing to regular increases

In planning, any erratic pattern should be avoided.

LONG-TERM DEBT RATIOS

The subject of debt capacity is discussed in Chapter 12. However, the management of shareholders' equity must always keep debt relationships in mind when planning future financing, whether they be debt or equity.

There are two principal ratios used by rating agencies and the financial marketplace in judging the debt worthiness (or the value of equity) of an enterprise:

- Ratio of long-term debt to equity.

- Ratio of long-term debt to total capitalization.

The first ratio is calculated as:

![]()

It compares the investment of the long-term creditors to that of the owners'. Generally, a ratio of greater than 1 is an indication of excessive debt. However, a company ratio should be compared to others in the industry (the leaders) or to industry averages, such as those published by Dun & Bradstreet, Inc.

The second ratio is calculated in this fashion:

![]()

Again, a ratio of greater than 50%, as a rule of thumb, reflects excessive use of debt. Comparisons should be made with selected industry members (judged to be prudent business people) and industry averages.

OTHER TRANSACTIONS AFFECTING SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY

In the management of shareholders' equity, any actions that are expected to impact this element of the financial statements should be reflected in the plans—the annual plan or the long-range plan, as may be appropriate. While earnings and dividends have been discussed, there are a host of other transactions that might be involved, including:

- Repurchase of common shares

- Conversion of preferred shares or convertible debentures

- Dividend reinvestment programs

- Exercise of stock options

- New issues of shares

- Special write-offs or adjustments

Before approving any such actions or agreements on such matters, the management should consider their impact on debt capacity, especially where debt ratios already are high.

LONG-TERM EQUITY PLANNING

For those entities with a practical financial planning system, the long-term planning sequence might be something like this:

- The company financial management has determined, or determines, what is an acceptable capital structure and gets the agreement of management and the board of directors.

- As a step in the long-range financial planning, the amount of funds required in excess of those available is determined by year, in an approximate amount.

- Based on the needs over several years, the desired capital structure, the relative cost of each segment of capital (debt or equity), the cost of each debt issue, and any constraints imposed by credit agreements, or the judgment of management, the long-term fund requirements are allocated between long-term debt and equity.

- For the annual business plan, any actions deemed necessary in the first year of the long-range plan are incorporated with the other usual annual transactions to form the equity budget for the year.

This is another way of saying that, ordinarily, the needs of additional equity capital are known some time in advance. They can be planned to take advantage of propitious market conditions, under generally acceptable terms, with the result that the cost of capital is usually competitive.

Normally, good planning will let management know well in advance the amount and timing of the requirements; it is not a sudden discovery. And the company continues to move toward its desired optimum capital structure.

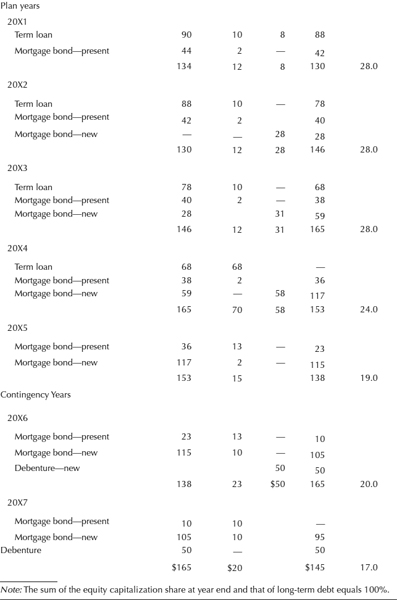

Allocating Long-Term Funds between Debt and Equity

Now, let us provide some illustrations of these points. Assume that the company management has agreed with the recommendation of the chief financial officer (CFO), concurred in by the controller, and that the capital structure should be:

Moreover, at the end of the current year (20XX) the capital structure is expected to be (unacceptable):

| Long-term debt | 31.5% |

| Shareholders' equity | 68.5% |

| Total | 100.0% |

EXHIBIT 13.6 LONG-TERM FUND REQUIREMENTS

In the process of completing the strategic planning cycle and the related long-range financial plan, the required long-term funds, without designation as to type or source, are estimated to be $67 million in three years, as reflected in Exhibit 13.6, for a program of substantial growth. Furthermore, after a slight hesitation in plan years 4 and 5, management thinks the cycle is to repeat again.

Now, here, are some comments looking to the year-by-year review for allocation purposes between long-term debt and equity:

- General. Since the cost of equity capital is highest, and issuance of new equity tends to dilute earnings, equity capital should generally be used sparingly—only to maintain the borrowing base and to reach and remain at the desired capital structure.

- Current year. At the end of the current year, equity will provide only 68.5% of capital (Exhibit 13.7)—as compared to management's target of 80% and a minimally acceptable level of 75%. Obviously, the debt share of capitalization is too high.

- Plan year 20X1. Given the start of an acceleration in annual earnings, management decides to hold the dividend payout ratio to 20%, and to borrow the needed $8 million under the term loan agreement (interest rate of 15%). The equity share of capitalization, even so, will increase from 68.5% to 72%.

- Plan year 20X2. With $28 million in new funds required, the company decides, in view of the heavy investment in fixed assets and a lower borrowing rate available (12%), to issue a new mortgage bond. Some of the funds will be “taken down” or received this plan year and the balance in the next year. Despite the high level of borrowing, the equity share remains at 72%. The management decides it can “live with” such a level for a temporary period, given the high level of income.

- Plan year 20X3. The balance of the new mortgage bond proceeds covers the requirements with no reduction in the equity share of capitalization.

- Plan year 20X4. With the net income now at a level of $70 million, and a proposal by an insurance company to provide new funds through a new mortgage bond, management decides to (a) accept this new loan of $58 million and (b) pay off the more expensive term loan. Given the continued high level of earnings, equity capital at year end will provide 76% of the capitalization. This is within the minimally acceptable standard used by the company.

- Plan year 20X5. In this last year of the five-year long-range plan, management believes the growth cycle is ready to start again. Without going through the complete long-range planning cycle again, it asks the financial vice president to estimate fund requirements for two more years—the “contingency” years. This quick review discloses that another $50 million will be needed in 20X6, with possibly a limited amount required also in 20X7. Accordingly, to raise the equity capitalization to the desired 80% level (20X6 borrowings considered) and to provide the needed equity base for the 20X6 borrowings and expansion in future years, it plans for an issue of $50 million in equity funds.

EXHIBIT 13.7 LONG-TERM FUND ALLOCATION

The management and board of directors feel comfortable with the increased equity base both in the event of a downturn in business for a limited period, or should it need to borrow additional funds.

The summary of the planned debt reduction, new indebtedness to be incurred, shareholders' equity, and capitalization percentages is given in Exhibit 13.8. These planned capitalization changes also will be reflected in the statements of planned financial position for the years ended December 31, 20X1 through 20X5.

Other Suggestions in Managing the Capital Structure

The “Long-Term Equity Planning” Section provides guidance in allocating required funds annually between debt and equity. The disposition depends on the urgency of attaining a given preferred capital structure, or meeting debt indenture constraints, or other limitations. But managing the capital structure involves more than allocating the new capital needs between debt and equity. It also includes watching for signals that funding problems are slowly (or faster) developing, as well as providing safeguards against unwarranted action by the suppliers of funds.

A few of the steps that might be taken by financial management to avoid being caught off guard could include:

- Be sensitive to those product lines which provide the highest return on capital as compared to those that consume or require relatively heavy amounts of capital, and produce a low rate of return.

Thus, if a small share of the products requires, say, 70% of the new capital needs, and provides at least 70% of the return on capital, then the situation seems satisfactory. If, however, the products consuming 70% of the capital supply but a small return, then the matter requires careful monitoring. Perhaps a hurdle rate is needed by product line, or geographic area, or other factor. Then, careful estimates of requirements, by year, and expected return, by year, are made. Finally, actual performance then should be monitored to see if the expected increasing yields are forthcoming. Conservatism is required in predicting the capital requirements as well as the yield.

- Continuously monitor the equity markets in an effort to judge when new equity should be acquired.

There are several stock market indicators to be followed which provide clues on the strength of the market, whether the market is overvalued, and whether new capital stock may be sold without diluting earnings. Included are:

- The Standard & Poor's (S&P) 500 price earnings ratio, as well as the price/earnings ratio of the company stock.

- The S&P 500 dividend yield and the yield of the company security.

- Price-to-book ratio. Typically the price of a stock is considerably higher than its book value. One major reason is inflation, since book value understates the replacement cost of the underlying assets. Since about 1950, the S&P Industrials index has moved in a wide band defined in market bottoms as one times book value, and 2.5 times book value near market tops.

So, this ratio may be a signal as to whether the market is overvalued. This price-to-book measure sometimes is less significant than others due to the influence of large stock buy-back programs, corporate restructuring, or merger frenzy.

- The market breadth. Changes in the Dow Jones average versus the S&P 500 or the Nasdaq index.

EXHIBIT 13.8 SUMMARY OF PLANNED CHANCES IN CAPITAL STRUCTURE

The relative trading volume. A high volume of, say, more than 200 million shares traded is said to be the sign of a strong market. Such factors, as well as the advice of investment bankers, may aid management in deciding on the approximate timing of a new stock issue.

- Be careful in the search for the lowest cost sources of capital.

Not only must the cost be competitive, but the method and terms should be acceptable. Thus, in a private placement, perhaps the provisions should include a buy-back option to avoid the creation of a major voting block. Or maybe the acquisition of a cash-heavy source (existing cash balances and high cash flow) may be feasible.

- Periodically check the cost of carrying current assets versus the return.

Must a switch be made from asset intensive activities to low-cost service type business?

- Analyze existing investment in assets for sales candidates or improved utilization possibilities.

Strategic planning implies more than calculating the changes in each asset category each year, based on expected operations and existing turnover rates. It requires an analysis of turnover to see where improvements can be made (e.g., use of just-in-time [JIT] inventory methods) or idle assets, such as land which may be sold.

- Relate predictable seasonal asset investment patterns, or cyclical ones, to incentives so as to reduce capital requirements.

Customers can be given special terms for early orders or early payment. Or, if an economic upturn is anticipated, this knowledge can be used to an advantage in inducing earlier-than-usual orders.

Proper strategic planning should look beyond operational expectations to wise asset usage (and prudent use of supplier credits).

SHORT-TERM PLAN FOR SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY

In terms of management of shareholders' equity, the emphasis should be on planning—especially long-term planning so as to achieve the proper capital structure and use it as the basis for prudent borrowing. Additionally, the many other aspects already discussed need to be reviewed, and policies and practices developed or continued that will enhance the shareholders' value.

Having said this, the annual business plan for the next year or two should reflect all anticipated near-term actions that impinge on the equity section or on the financial statements. When completed, that section of the plan relating to shareholders' equity may be summarized as in Exhibit 13.9.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Dividend Reinvestment Programs

A supplementary facet of dividend policy is the question of offering a dividend reinvestment plan to investors. Under such a plan, shareholders may invest their cash dividends in the common stock of the company—sometimes at market price, usually with no brokerage fee, and sometimes at a discount, that is, 5% of the market price. Many dividend investment marketing plans utilize shares purchased in the open market. Others permit the issue of original shares directly by the company.

Dividend investment plans have now been expanded to permit the purchase of additional shares over and above the dividend amount with cash payments—sometimes with a ceiling on such quarterly or annual purchases, say, of $5 million. Also, some companies permit the preferred shareholders or bond holders to purchase common shares with the quarterly or semiannual dividend or interest payments.

EXHIBIT 13.9 BUDGET FOR SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY

Financial officers should consider such a practice. The costs of operating the program versus the probable level of participation (based on industry experience, etc.) should be weighed. Trustees who handle such plans for other corporations, competitors or otherwise, may be helpful sources of information.

Stock Dividends and Stock Splits

This chapter is not intended to be a treatise on the types of stocks that may be issued or their advantages or disadvantages, and the many related subjects. However, the controller should be aware of the accounting treatment of stock dividends as well as stock splits and the arguments for and against the issuance of such designated shares.

Basically, the New York Stock Exchange has ruled that the issuance of 25% or less of stock is a stock dividend and that the issuance of more than 25% is a stock split. Both are essentially paper transactions that do not change the total equity of the company but do increase the number of pieces or shares. However, depending on state law, the accounting treatment may differ. Thus a stock split may not change retained earnings; only the par or stated value is changed. A stock dividend may cause the paid-in-capital accounts and retained earnings to be modified (but not the total equity).

The controller should be aware of the pros and cons, the expense involved, and the procedure for issuance of dividends, or splits, or reverse splits.

Repurchase of Common Shares

Another subject to be considered by the financial management is the repurchase of common shares. Conceptually, a company is enfranchised to invest capital in the production of goods or services. Hence it should not knowingly invest in projects that will not provide a sufficiently high rate of return to adequately compensate the investors for the risk assumed. In other words, the enterprise should not invest simply because funds or capital are available. Business management should identify sufficiently profitable projects that are consistent with corporate strategy, determine the capital required, and make the investment. Hence shareholders might interpret the purchase of common stock as the lack of available investment opportunities. To some, the purchase of company stock is not an “investment” but a return of capital. It is “disfinancing.”

Some legitimate reasons for the purchase of common stock are:

- Shares may be needed for stock options or employee stock purchase plans, but the management does not wish to increase the total shares outstanding.

- Shares are required in the exercise of outstanding warrants or for the conversion of outstanding convertibles, without issuing “new” shares.

- Shares are needed for a corporate acquisition.

Some guidelines to be heeded in considering a decision to repurchase shares are:

- If a company is excessively leveraged, it might do well to use cash to pay down existing long-term debt to reach the capital structure goal it envisages and not repurchase common shares.

- The management should examine its cash requirements for a reasonable time into the future, including fixed asset requirements, project financing (working capital) needs, and other investment options, before it concludes that excess cash is available and that the equity capital genuinely is in excess of the apparent long-term demands.

- The cash dividend policy should be examined to see that it helps increase the market price of the stock.

- Only after such a review, should the conclusion be reached to dispose of “excess equity” through the purchase of the company stock.

Given these conditions, timing may be important. Thus, if the market price of the stock is below book value, the purchase of shares in fact increases the book value of the remaining shares. It might be prudent to purchase shares below book value rather than at a price that dilutes the shareholders' equity.

Capital Stock Records

An administrative concern in the management of shareholders' equity relates to the maintenance of necessary capital stock records. In the larger companies, the stock ledgers and transfer records are kept by the transfer agent. The information relative to payment of dividends on outstanding shares, for example, is secured from this source. Quite often, the database is contained on computer files, and any number of sortings can produce relevant data regarding ownership:

- Geographic dispersion

- Nature of owners (individual, institution, etc.)

- History and timing of purchases

- Market price activity

- Volume of sales and the like

Under these circumstances, a ledger control account for each class of stock is all that is maintained by the company.

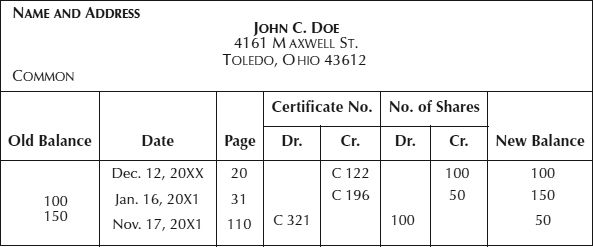

If a corporation conducts its own transfer department, then a separate account must be maintained for each stockholder regarding each class of stock. An illustrative simple form is shown in Exhibit 13.10. The ledger might contain:

- Name and address of holder with provision for address change

- Date of changes in holdings

- Certificate numbers issued and surrendered

- Number of shares in each transaction

- Total number of shares held

EXHIBIT 13.10 CAPITAL STOCK LEDGER SHEET

Optional information might include a record of dividend payments and the data mentioned above for the computer files.

The stock ledgers should be supported by registration and transfer records that give the details of each transaction. Transfer journals are not required in all states. In circumstances that justify it economically, computer applications may be desirable.

Finally, of course, sufficient records must be maintained to satisfy the reporting needs of the federal and state government—foreign holdings, large holdings, and so on.

The management, of course, has an interest in monitoring, perhaps monthly, large holdings and the changes therein. Such a review may provide signals about possible take-over attempts and the like. For this purpose, as well as soliciting proxies, the services of outside consultants, such as Georgeson & Co., that specialize in such matters, may be used.

1. Reprinted with permission from pp. 270-278 of Steven M. Bragg, Financial Analysis (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ: 2000).