Management, Security Law, and Policies |

CHAPTER3 |

MANAGERS ARE NOT USUALLY LAWYERS; therefore, it is best to leave legal interpretations, advice, and legal procedures to the attorneys. Even those who are attorneys know the joke about a lawyer who represents himself or herself has a fool for a client. However, there are some aspects of security law that managers must be knowledgeable about to avoid creating legal problems for the corporation and for themselves further down the road. Main areas that are of particular interest in this regard are employment law related to security and policies, intellectual property, the use of company equipment and facilities, cyber crime and cyber law, electronic monitoring of employees, and forensic analysis and evidence preservation. In this chapter, we will present a basic orientation to these key legal issues.

Chapter 3 Topics

This chapter:

• Describes strategic security initiatives as the use of power and organizational politics to bring about broadly conceived outcomes.

• Explains security incidents from attacks or disasters.

• Illustrates the information security management life cycle (ISML) and its iterative stages.

• Covers security and employment law and security policies.

• Disscusses virtual work and related security and privacy issues.

• Explains intellectual property (IP) including trade secrets, copyrights, trademarks, and patents.

• Describes employee surveillance and privacy issues.

• Introduces forensics and the activities in collecting and preserving evidence and answering questions for legal purposes.

When you finish this chapter, you should:

![]() Understand how management, security law, employment law, and policies are related.

Understand how management, security law, employment law, and policies are related.

![]() Know security-related legal aspects of mobile and remote work.

Know security-related legal aspects of mobile and remote work.

![]() Be able to identify the nature of intellectual property so that these assets can be classified for a risk assessment process.

Be able to identify the nature of intellectual property so that these assets can be classified for a risk assessment process.

![]() Know what is permissible regarding employee monitoring and implications for policies.

Know what is permissible regarding employee monitoring and implications for policies.

![]() Understand the basic legal aspects of forensic analysis and preservation of evidence and the chain of custody concept.

Understand the basic legal aspects of forensic analysis and preservation of evidence and the chain of custody concept.

3.1 The Management Discipline

The functions of management include planning, organizing, directing, and controlling organizational resources [1]. Planning may be broken down into operational, tactical, and strategic levels [2]. Operational planning targets ways to gain efficiencies and cost-effectiveness in daily transactions. Tactical planning involves determining the incremental steps that are needed to achieve a strategy; strategic planning involves structured processes that lead to the realization of an envisioned future by leveraging the organization’s core competencies [3–5]. How management goes about this planning divides along the lines of using processes that are scientific, formal, and structured (e.g., Semler, [6] 1997) or using techniques that involve artistry, creativity, imagination, and intuition (e.g., Stacy 1992 [7]).

In Focus

The strategy concept has been conceptualized and defined differently by experts in the field. Some consider it to be a scientific plan for the future, others consider it to be the expedient use of resources to capitalize on major goals, and others consider it an “ability” to envision the future and inspire others to help achieve it. Michael Porter is among the most recognized experts in strategy because of his centrist views about strategy. His practical approach deals with the forces that affect decisions and corporate positioning and his use of the process of examining strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—called a SWOT analysis.

Managers organize resources by allocating their budgets and time to tasks so that they can fulfill their plans in support of organizational objectives. Organizing resources aims at the operational and tactical levels of management while keeping the strategic plan in mind [1]. The directing activity consists of clarifying goals and setting expectations with employees and superiors. The controlling activity involves conducting evaluations of business and employee performance, monitoring performance and comparing against plans, making adjustments, and creating a feedback loop for continuous organizational improvement [8].

3.1.1 Management Initiatives and Security

An initiative may simply be thought of as a project, and as with planning, initiatives may be operational, tactical, or strategic [1]. A strategic initiative is a product development or service activity that is used to gain competitive advantage [9, 10] and requires “long-term” commitment in time and resources to produce or provide [11]. Strategic initiatives therefore differ from tactics and operational initiatives in that the former is a blend of various analyses, behavioral techniques, and the use of power and organizational politics to bring about broadly conceived outcomes [12], whereas tactical initiatives are managerial actions that enact a strategy [13] and operational initiatives are the daily routines that result from management actions [8]. As such, realizing a strategy comes by way of product or service initiatives [14].

Security management comprises planning, organizing, directing, and controlling organizational resources (human and non-human) aimed specifically at securing the organization at operational, tactical, and strategic levels. Security initiatives include identifying and prioritizing business and security needs; determining the value of assets; defining, developing, overseeing, and monitoring security processes and procedures; producing and executing contingency plans; and evaluating, comparing, and selecting security technology to mitigate risks and prevent vulnerabilities from being exploited [15].

Security management may be a general management function or it or may be divided among designated security management positions; however, the management of operational, tactical, and strategic levels of security tends to ascend upward through the management echelon. For example, line managers or supervisors may oversee network and computer administrators who configure and deploy security solutions. The line managers monitor and report security threats and security needs to midlevel managers, who are usually tasked with allocating budgets and making decisions about security technologies and procedures [16].

Midlevel managers and line managers together are responsible for the implementation of the security architecture and the enforcement of security policies, and they report security and policy requirements upward to senior management. Senior managers work with the legal department and human resources to develop security policies, and they work across the organization to develop security strategies. They may also direct reviews and audits of security and ensure business continuity and/or recovery from disasters [15].

3.1.2 Information Security Management

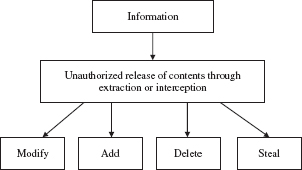

Although managers are responsible for helping to ensure the security and well-being of employees, information security is at the core of the security management functions. Computer security often refers to those efforts to secure computing devices such as desktops and laptops [17], whereas network security often refers to those efforts to secure the communications and data transmission infrastructure [18]. All of the efforts designed to protect computers and networks are primarily geared toward protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. This is partially accomplished by establishing preventive and corrective measures to address unauthorized access to information that would lead to adding, deleting, modifying, or stealing. Figure 3.1 illustrates the broad categories of threats to information security.

FIGURE 3.1

Information security threats.

We have defined the concept of a threat previously, but for the purposes here relative to information security, we may view a threat as the potential for a security breach due to vulnerabilities. When vulnerabilities are exploited in attacks, the attacks can be either passive or active. A passive attack may be designed to simply steal information without the victim realizing it. An active attack may attempt to corrupt information or cause a disruption of a service or prevent access to critical information resources.

Threats may represent natural disasters, or they may represent the potential for human-induced incidents. Incidents are the realization of a disaster, such as a hurricane that obliterates an operations center or an attempted or successful attack by one or more people to bring down an operations center network. Human-induced incidents may be the result of accidental errors or intentional attacks by either company insiders (e.g., employees or contractors) or outsiders who do not work for the company. Intentional attacks aim at exploiting vulnerabilities that allow unauthorized access to information, hardware, networks, or software such as operating systems, database management systems, or applications. One classification of an intentional attack involves theft of information by identity thieves or corporate spies. Table 3.1 provides some examples of information of interest to those who perpetrate such an attack.

To handle the threat risks, there are a variety of technologies and techniques available. For instance, access control applications coordinate who has what type of access to which resource. In this example, a systems administrator may have login access to a computer and may be authorized to read, add, and modify system configuration files, whereas non-administrators who have login access to the computer may only have permission to read them. When managers and their security assurance teams determine the threats and vulnerabilities to information resources, they assess the likelihood of attacks and the severity of consequences from successful attacks. Managers must then weigh the threat risks (exposure) and the value of the assets against management priorities, timelines, and budgets [16].

TABLE 3.1 Examples of Information Assets

|

• Current customer lists: Customer information provides competitors with “competitive intelligence” about what a company is providing and to whom, which may facilitate opportunities to undermine them. • Supplier, distributor, and contractor lists: These lists enable outsiders to determine potential vulnerabilities. • Marketing plans: These include sales projections, statistics, pricing, forecasts, financial information, and promotional strategies, which can be exploited by a competitor. • Research and development: This information pertains to intellectual property, strategic directions, product lines, preliminary research findings, and new product announcement dates. • Operational information: This pertains to capacity, expansion, liquidity/working capital, austerity plans, and internal costs of doing business (i.e., profit margins). |

3.1.3 Information Security Management Life Cycle

The information security management life cycle (ISML) consists of iterative stages. The stages typically include security analysis and planning, security design, security testing, security implementation, and security audit and review. Because the stages are iterative, feedback from the audits and reviews is then used the analysis and planning stage, which begins the cycle again. In the security analysis and planning stage, the assets and resources are classified according to their value, sensitivity, and exposure. Security requirements are developed according to the identified threats and vulnerabilities. Risk mitigation strategies and contingency plans are established, along with business continuity and recovery plans.

In Focus

A systems development life cycle (SDLC) is a structured set of processes used to produce a product or deliver a solution. An ISML is similar in this regard.

This stage is followed by a design stage, when security policies and procedures are created. The security design stage has a logical and a physical design aspect. The logical design involves developing the breadth and depth of the security measures that are to be implemented. The physical design involves the cost/benefit and risk assessment–based selection of technologies and techniques to be used in the implementation of information security. Depending on the technology or technique, a pre-implementation testing phase may be conducted to determine the quality and impact of the planned security measure. The security testing stage may run concurrent with or after the implementation of security measures, followed by the development of security criteria and checklists used when the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information are audited and reviewed [15].

3.2 Security Law and Cyber Knowledge Work

Knowledge work is a term coined by Peter Drucker to describe jobs that derive their products and services from intellectual/cognitive tasks, and the Internet is often an important tool in knowledge work. Yet because information can be easily accessed and shared, this feature raises a variety of legal and security issues that managers need to consider. Among these issues are how information assets and intellectual property are used and how employees conduct their online activities, such as when posting information or comments in newsgroups, blogs, or social media that may affect the company. If an employee violates the law, depending on the nature of the violation, it may open a company to either civil or criminal liabilities, or both. In the United States, civil litigation seeks compensation for injuries to individuals or corporations, whereas the criminal justice system seeks to deter people from committing crimes and outlines punishments for those who inflict injury upon others [19]. Within this rubric, court decisions are called case law, whereas statutes are created from federal government and state legislation.

Statutory law may include criminal or penal law. Criminal violations of the law can be felonies, that, depending on jurisdiction, may be subdivided into four classes, where class “A” represents the most severe and class “D” represents the lesser felonies. Misdemeanors are often divided into class A” (more severe) and class “B” (less severe). The standards of proof to determine that an offense has occurred differ between civil and criminal systems. In civil litigation, a finding of fault is based on the greater evidentiary weight (a preponderance of the evidence), whereas in criminal proceedings, guilt is decided based on the higher standard of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” as decided by a judge or jury [20].

One of the major challenges for managers is that governments and their development of laws and legislation move slowly because, especially in the United States, there is the presumption that the slow-moving machinery of democracy promotes stability, but diffusions of technologies and organizational practices evolve and become implemented much more quickly. For instance, it has been debated (and decided differently) in many of the states in the United States as to whether a faxed signed document is an original, or a replica or copy, or nothing more than a series of “ones and zeros” that traverses a telephone line [21]. Likewise, there are different consequences and ways to adjudicate grievances depending on whether it is tried in a state or a federal jurisdiction [22]. Thus navigating these digital/cyber law issues is tricky and, in many instances, undecided. Having good security policies and well-written procedures in place is crucial in this regard.

3.2.1 Security, Employment Law, and Policies

If we are talking about security policies related to employee misconduct, we are necessarily talking about employment law. Under common law, a contract for employment for other than a definite term is generally terminable at will by either party. Accordingly, employers may dismiss their employees at will for good cause, for no cause, or even for a cause that might be considered morally reprehensible, even without being guilty of a legal wrong. However, recently, the courts have delineated a growing number of implied contract and public policy grounds for allowing suits to be brought against former employers under federal- and state-enacted rules (see Novosel v. Nationwide Insurance Company, 1983 [23]). There are also a growing number of tort suits [24]. A tort is defined as a breach of legal duty to exercise reasonable care that proximately causes injury or damage to another. This is a civil wrongdoing that does not arise from a breach of contract.

Because there are many international, federal, and state (or province, geographical, or local) laws that can be involved when it comes to security law, employment, and policies, when organizational policies are crafted it bears repeating that it is important to have legal guidance (such as from corporate attorneys in the legal department) along with the involvement of the human resources department [25]. Still, the implementation and enforcement of policies are often the burden of management [26], and so managers cannot afford to be ignorant of the law—and ignorance of the law is not a defense in court [27].

In Focus

Employment at will is a common-law employment doctrine that allows employers to dismiss employees without cause, and employees to quit without giving reason or notice. This contrasts with employment contracts and unionized employment.

In the United States, statutes require that an applicable regulatory agency (depending on the offense) impose penalties or fines for failure to notify employees of their rights and responsibilities [24]. Security policies therefore are an important component of this notification. Their main function, besides helping to ensure a more secure organization, is to reduce risk, and part of risk reduction is to reduce exposure to lawsuits. Because former employees are a main source of suits against companies, especially when it comes to policies and employment discharge, managers must exercise due care and due diligence in preventing problems and in handling employee misconduct and discharge issues [27]. This might include specifying what actions are worthy of immediate termination, what actions are subject to censure and/or corrective actions, and specifically excluding conduct related to policies for which there are extant laws, regulations, or statutes that could bring about a conflict in the interpretation and demand litigation to resolve or clarify by adjudication [25].

Realize that there are important differences between policies, guidelines, and procedures. Policies, in general, make clear acceptable and unacceptable actions in an organization and dictate the consequences for negligence or intentional failure to comply with communicated policies. Guidelines are rules of thumb that make suggestions about how to implement the spirit of the policies, and procedures are the detailed instructions that people must follow to implement the letter of the law intended by the policies. Policies need to delineate those actions that will result in immediate discharge from the company (and include language in the policy that states, in essence, any violations of the law), and those that will subject an employee to a corrective action process [25, 27].

In Focus

The main difference between a guideline and a policy is that a guideline tells management and employees what they should do about a problem. A policy tells management and employees what employee duties are and what they can expect from management as a result. As such, a policy may become a contract [24].

Regardless of whether a company is incorporated (or operates) in an “employment at will” state, it is prudent to have and to use a corrective action process when it is called for. Although technically the employment-at-will doctrine allows companies to discharge employees without cause, a company that does so without using due process (such as through a corrective action process) may open itself up to wrongful discharge suits [24, 25]. For example, most states, provinces, and districts in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and several states in the European Union (EU) including France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, require a “good faith” dealing with employees [28]. Good faith means dealing honestly in one’s conduct. Without proof of this basic treatment, discharged employees may file a suit based on defamation, infliction of emotional distress, malice, and bad faith dealings, or may use a discrimination defense, regardless of an employment-at-will doctrine, that a governing state may allow its incorporations [29].

Whether an employee might win the suit in a court of law is not the complete picture of the financial interests in the issue. First, litigation is expensive to the corporation, even if there are retained or corporate attorneys on staff. Second, even if the corporation wins in court, if a complaint goes to trial there could be a negative image or bad press conveyed. This could damage the corporation’s reputation and negatively affect future recruitment of highly sought-after talent, make it more difficult to secure additional financial investments, or even negatively affect sales. A corrective action process can help to alleviate this problem.

In Focus

Corrective action is a formal process during which management and the legal and human resources departments implement steps that give employees a fair opportunity to correct counterproductive behaviors.

By corrective action, the due process concept simply means notifying an employee of a deficient or negligent behavior, outlining what is required to achieve competence, giving a timeline and specific instructions to overcome the incompetence, listing the support that management is willing to offer to achieve those ends, providing a definite but reasonable timeframe for the employee to achieve competence, and naming the consequences for remission, which typically means employment discharge [25].

In Focus

An employer who tries to avoid potential discharge suits by making a work environment so hostile and onerous that the employee quits of his or her own volition may bring about a constructive discharge or harassment suit against the company, even in a state that utilizes an employment-at-will doctrine.

So how does this apply to information security, policies, and the law? Suppose you had a male employee who downloaded sexually explicit material on a company laptop, but the material did not violate child pornography laws—and a female coworker who sat next to the male employee on an airplane during a business trip saw it while he was viewing the material, and she subsequently filed a sexual harassment charge? Immediately, management has to confront what policies were established by the company for company equipment use and corporate conduct while at work or while “virtually” working.

3.2.2 Virtual Work, Security, and Privacy

Virtual work is a generic term used to describe company-sanctioned work tasks that occur away from the office. Some refer to this kind of work as telework, virtual teaming, mobile work, e-commuting, or some other moniker that essentially means doing company business outside the purview of the traditional corporate office, and it almost always means using some sort of technology and media to facilitate. As such, the technology and media “follow” the virtual worker as he or she travels or operates from a location other than the office (i.e., from a remote location). If that location happens to be a home, a hotel room, or some other “personal space,” there are important intervening considerations for managers to balance relative to security and privacy. An invasion of privacy is an unjustified intrusion into another’s reasonable expectation of privacy [30].

Some common intrusions that often give rise to lawsuits are public disclosure of private facts, the use of private information for the purpose of placing someone in a false or negative light in public, or misusing a person’s identity or personal information for commercial gain or exploitation. In organizations, suits based on the theory of intrusion often arise from illegal searches and unauthorized electronic surveillance where the surveillance serves no business purpose or need [31]. In most organizations today, especially in knowledge work, people work not only in conventional offices, but also on the road or from home. Working from locations other than the workplace (virtual work) has major implications for security because laws and regulations governing the conventional office are being extended to home offices and virtual facilities.

More specifically, virtual work raises questions of employer liability for injuries sustained at home, or those incurred in transit between home and office, and whether these may be covered under worker’s compensation, especially in cases where the employer may require employees to work away from the office. In 1999, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued an advisory letter on home-based workers, apparently requiring employer responsibility for home-based employee site safety. That letter generated so much controversy that OSHA subsequently diluted the requirement [32]. Nevertheless, employers are still required to report injuries that occur from work performed at home and to have some knowledge of employee home office environments.

Tonsing [33] noted various liability issues that virtual work creates, including jurisdictional issues involving situations where employers and employees reside in or are working in different states. This issue is commonly referred to as the “clash of laws.” In the United States, litigation resulting from an Internet transaction is normally determined based on a state’s “long arm” statute, which provides that a state can assert jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant who commits a tort, transacts business, or has some contact with that state [22].

Another recurring concern of employers with regard to virtual work has to do with ensuring the confidentiality of work products in the home or other environment outside the office. This can also have liability implications, where, for example, the employee is in possession of customer data or has in his or her possession employer trade secrets. Sensitive information and software assets may reside on laptop computers or mobile devices such as Blackberrys, iPhones, and so forth that can be easily lost or stolen. To highlight this point, in 2010, AvMed Health Plans Inc. reported the theft of two laptops containing unsecured social security numbers and health-related information for roughly 208,000 subscribers [34].

Conversely, there is also a personal risk for the employee, even if the employee regularly encrypts company information, because a legal “discovery” request may lead to the exposure of his or her private information encrypted using the same technologies and techniques that may reside on that computer system [28]. For these and other reasons, it is important for the protection of both employer and employee that company assets are used only for company purposes—and that employees do not use equipment such as laptops for “personal” materials or functions. This should be explicitly stated in company security policies.

A further area of concern in virtual work and security relates to the ability of management to monitor and control employee security behavior, which can run in conflict with privacy. It is generally taken for granted that employees may be under electronic surveillance in the workplace, which includes monitoring employees’ computer files and email, web access, and voice mail within the ordinary course of business [35], and many employers would like to extend this surveillance ability to the remote workplace, including the home.

Although various governmental constitutions differ with regard to privacy rights, neither the Canadian Charter nor the U.S. Constitution, for example, contains provisions that explicitly define privacy rights in terms of personal information or data [18]. In the United States, the home has been an iconic bastion of privacy [36]. This may leave open the possibility for employer liabilities for certain crimes, especially in cases where managers “should have reasonably known” about them or failed to provide policies to address their prohibition in lieu of specific laws, ordinances, statutes, or regulations such as in the misuse of information and information systems [24].

Moreover, in cases where managers are not aware of, and could not reasonably foresee, illegal activities undertaken by employees, employer immunity to liabilities may be open to challenge if there is a company-required commingling of assets (software and hardware) used both in the office and at home or remote locations [27]. Next, because employees sometimes use the same home computer for both work and personal business in spite of policies prohibiting the practice [37], this raises the question of whether employers have a right to extend surveillance to the home office environment to protect their legitimate interests and take precautions from liabilities [38].

When an employee logs in to his or her employer’s computer network using a home computer, the employer has the potential of accessing the employee’s private files and may see what other files the employee is working on during “work time” [39]. If litigation results between the employer and employee, the employer may obtain a court order allowing it to inspect and copy an employee’s home computer’s storage, as happened in the Northwest Airlines case where the airline claimed employees had planned “a sick-out” in order to cripple the airline [40].

Legal and private practices at home, such as downloading explicit sexual content from the Web, may land virtual workers in trouble if the materials are stored on company-owned equipment, and there may be employer tort liabilities from unreasonable intrusions. Among the considerations are the degrees to which employees have a reasonable expectation of privacy and the presence of a legitimate business justification that overrides the privacy expectation [41].

3.3 Intellectual Property Law

Intellectual property (IP) refers to corporate proprietary information, data, trade secrets, copyrights, branding, trademarks, patents, and other materials, methods, and processes claimed as owned by a company, and thus IP is considered assets of a company. IP has value; it costs money to create it and to protect it, and the value can be diminished by someone’s actions even if actual damages are hard to determine [42]. The ease with which information can be distributed over the Web has apparently contributed to common violations involving IP [43]. As part of risk assessment, IP should be classified according to type and sensitivity of the information; in managing risk, IP needs to be protected commensurately. As part of this, organizations need to develop written policies and to conduct training on the proper care and handling of IP.

3.3.1 Trade Secrets

Trade secrets consist of formulas, methods, and information that are vital to company operations. Although employees are generally under a duty of loyalty to their employers not to misappropriate trade secrets by disclosure to competitors, to help protect trade secrets, employees and outside parties to whom trade secrets are divulged are usually asked to sign non-disclosure agreements. People who violate the duty to keep trade secrets confidential commit a tort. To qualify as a tort, the offender must have had a legal duty to the injured and must have breached that duty, and damage must have been inflicted as proximate result [44]. In addition to unauthorized disclosure, trade secrets may be lost due to industrial espionage, electronic surveillance, or spying.

3.3.2 Patents

Patents are inventions to which the patent holder is granted exclusive use for a period of time by federal law (in the United States). A patent owner may profit by granting licenses to others to use the patent for fees or royalties. Unlike trade secrets that are to remain confidential, when inventors patent an invention with the Patent Office, they must describe it in such detail that it can be copied. This is so courts can determine if the invention is patentable or if an infringement has occurred. Once a patent has expired, the invention enters the public domain, where anyone can use it. There are different kinds of patents, but most patents that are related to information security are “utility” patents. To be eligible for patent as a utility, the process, machine, or composition must be novel (that is, it must not conflict with a prior pending application or previously issued patent), and it must have specific and substantial usefulness [29].

In Focus

2010 SCO v. Novell Litigation: Following a 3-week jury trial, attorneys won a unanimous verdict for Novell in SCO v. Novell, a case widely watched by members of the open source software community. SCO’s business model was to convince Linux users to pay license fees to SCO, based on the notion that Linux infringed certain UNIX copyrights, which SCO claimed it had acquired from Novell. Novell stated that it, not SCO, owned the UNIX copyrights, and SCO sued for slander of title, seeking damages of several hundred million dollars. Novell had earlier sought and obtained a summary judgment in the case, when the court ruled that Novell in fact owned the copyrights. SCO appealed to the Tenth Circuit, which reversed and remanded the case for a jury trial. At the conclusion of the trial, the jury unanimously agreed that Novell, not SCO, owned the copyrights, thus denying SCO’s damage claims. In post-trial rulings, Judge Ted Stewart denied SCO’s claims for specific performance and breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. Judge Stewart also granted Novell judgment on its claim for declaratory judgment [45].

3.3.3 Copyrights

Copyrights are protections afforded by federal law to authors of original works. Under Section 102(a) of the Copyright Act, works include music, literature, software, semiconductor patterns and electronic programming, graphics, motion pictures and audiovisual recordings, and the like.

In Focus

Copyright protections do not protect an idea; they only extend to an original expression of an idea.

In most cases, copyrighted work should be registered with the Copyright Office, but this is not required in order to protect a work. For example, in some cases, simply placing a © after the copyright owner’s name and the year is sufficient to create a defensible protection from infringement. Most individual copyrights hold for the lifetime of the author plus 70 years. For corporate authors, the protection extends to 95 years. There are instances where copyright protections may be limited [42]. Two such limitations are compulsory licenses and fair use. Compulsory licenses permit certain limited uses of copyrighted materials upon payment of royalties. Fair use allows reference to copyrighted materials for the purpose of criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research. Fair use is determined by (1) the purpose for which the materials were used, taking into consideration for-profit versus non-profit usage, (2) the nature of the copyrighted work, (3) the amount and proportion used in relation to protected work, and (4) the effect of the use on the market value of the copyrighted work. Owners can transfer copyrighted works to others, and under most cases when work is done for hire, there is typically an implied if not explicit ownership transfer [44].

3.4 Employee Surveillance and Privacy

To augment security, companies are increasingly using employee-monitoring (or surveillance) techniques. Recent studies found that in 1999, 67 percent of employers surveyed electronically monitored their employees, but by 2001, that number had grown to 78 percent; by 2003, 92 percent of employers surveyed indicated that they used electronic monitoring of employees. Most of the employers surveyed monitored employee web surfing, more than half reviewed email messages and examined employees’ computer files, and roughly one-third tracked content, keystrokes, and time spent at the computer [46]. The majority of workplace surveillance to date has consisted primarily of electronic observation of web surfing activity, monitoring emails, and telephone call monitoring for office workers (for quality assurance and training purposes), and global positioning satellite (GPS) tracking of mobile workers [47]. However, the breadth and depth of surveillance is growing.

3.4.1 Video Surveillance

Fairweather [48] determined that video surveillance of employees has become commonplace in many vocations and locations. A survey by Harvey [46] showed that of companies surveyed, only 18 percent used video surveillance in 2001, but by 2005, that number had climbed to 51 percent, and 10 percent of the respondents indicated that cameras were installed specifically to track job performance. The uses of video surveillance to monitor work activity may be supported by an analogy to the “plain view” doctrine, which allows a company to monitor employees in plain sight. This position is strengthened if the company takes overt action to notify its employees of the practice [49]. Areas where video surveillance is common are in computer server rooms, accounting or bookkeeping and payroll offices, stockrooms and warehouses, and manufacturing areas.

3.4.2 Privacy and Policy

As we indicated earlier, one of the central issues in terms of surveillance initiatives concerns worker rights to their privacy versus employer rights to know what workers are doing, along with their responsibilities to report illegal activities. Laws have tended to support the rights of corporations to inspect and monitor work and workers, which arises from needs related to business emergencies and the corporation’s rights over its assets and to protect its interests [50]. Employees may use email or the Web inappropriately for purposes such as disseminating harmful information, infringing on copyrighted or patented materials, harassment, corporate espionage or insider trading, or acquiring child pornography. In these instances, the courts have leaned on the principle of discovery to allow inspection, granting any party or potential party to a suit including those outside the company access to certain information such as email and backups of databases, and even to reconstruction of deleted files [51]. There are protections in place to mitigate unreasonable search and seizure, such as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, which defines an electronic communication as:

Any transfer of signs, signals, writing, images, sounds, data, or intelligence of any nature transmitted in whole or in part by a wire, radio, electromagnetic, photoelectronic or photooptical system that affects interstate or foreign commerce, but it does not include the radio portion of a cordless telephone communication that is transmitted between the cordless telephone handset and base unit, wireless networks, any wire or oral or video communication, any communication made through a tone-only paging device or any communication from a tracking device. [52]

The original intent of the law was to protect one from the interception of communications not otherwise subject to interception, but the U.S. Patriot Act (HR 3162) has vastly expanded the powers of government and enforcement agencies to conduct surveillance and communications interception pertaining to criminal activity [50]. From a legal perspective, the extent of an employee’s expectation of privacy often turns on the nature of an intended intrusion. With the exception of personal containers, there is little reasonable expectation of privacy that attends to the work area. That is, a worker may have reasonable expectation of privacy in personal possessions such as a handbag in the office, but the law holds that employers possess a legitimate interest in the efficient operation of the workplace. One aspect of this interest is that supervisors may monitor at will that which is in plain view within an open work area, and perhaps even within a home if a home is used for teleworking [53].

With the rise of social media such as Facebook, YouTube, and MySpace, people are increasingly giving up their privacy by posting intimate and compromising photos, videos, and other information. Employers are using information posted on these sites for making hiring decisions and, in some cases, terminating employment. These sites are also sources of compromise, including dissemination of IP or defamatory postings. To help prevent company liabilities or other security issues, corporate policies need to include the protocols for appropriate online behavior that might affect the company or the company’s interests [54].

3.4.3 Surveillance and Organizational Justice

The legal protections afforded employers combined with increasing technological sophistication and decreasing costs are allowing companies to monitor the actions of workers more closely than ever before [48, 55]. A concept that originated in the military, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR), has now made its way into the business lexicon. Software that covertly monitors computer activities and surveillance devices are being fashioned to blend into the environment by hiding them in pens, clocks, or bookends, which has a dampening effect on employee surveillance awareness regardless of employer notifications. This creates a psychological bind on employees who know they are being monitored, but the unobtrusiveness of the technology and devices make them seem innocuous [55]; moreover, the concepts of privacy and security are not simply legal matters. Privacy is an element of the psychological state of security. When people’s perception of privacy is reduced, there can be deleterious consequences for work performance.

3.5 Cyber Law and Cyber Crime

Cyber law can be thought of as a collection of extensions to existing law administered under federal, state, or local law. For example, the federal cyber crime statute 18 U.S. Code § 1030, among other stipulations, makes it a crime for anyone to knowingly access a computer without authorization or exceed authorized access of systems that involve national defense or foreign relations, or any other restricted data with reason to believe that such information could result in injury to the United States, including interstate or foreign commerce. It also prohibits willfully communicating, delivering, transmitting, or in any other way allowing the protected data to be leaked to any person not entitled to receive them. This statute and others have been used to combat unauthorized intrusions into computer systems and illegal access and use of intellectual property, financial records, medical records, and fraudulent online activities. States and local municipalities also enact cyber crime laws; for example, every state in the United States prohibits unauthorized access of computer systems and theft from them or damage of them by gaining unauthorized access [19].

3.5.1 International, Federal, and State Cyber Law

As presented earlier, there are jurisdictional issues related to various crimes and civil injuries committed over the Internet. There are situations where a violation can overlap with both civil and criminal prohibitions and with international, federal, and state laws. A common example is an infringement of intellectual property such as a copyright or a patent. Conversely, there have been cases where companies have assumed that their patents were infringed upon, only to learn that their patents were filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office but were not valid in a foreign country.

The viability of any legal complaint across national borders depends on the treaties the nations hold. For international guidance in America, the American Law Institute and the Foreign Relations Law of the United States are important resources; in Europe, check the Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime; and the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) outline rules and guidelines for conducting transactions across international borders [28].

Most of the “industrialized nations” have codified legal restrictions against the most common forms of cyber crimes, although how they are adjudicated, the penalties, and the jurisdictions are fluid and not always clear [44]. For the most part, there are prohibitions against intentionally gaining unauthorized access to (“hacking” into) computer systems to commit theft, cause damage, or commit other illegal offenses; attempting to damage or disable computer systems such as through denial of service attacks or releasing Worms or Trojans; attempting to extort money or create false identities using information gathered from intrusions or social engineering; threatening or harassing others online (cyber harassment); online stalking (cyber stalking); and misappropriating legally protected information, such as copyrighted materials [22].

3.5.2 Employee Behavior and Cyber Law

There are instances where employers may be held liable for employee conduct, both off and on the job. For example, off the job, if employees post confidential customer information or HIPAA-protected materials online, an employer may be held accountable depending on what precautions employers took to preclude such actions [27, 56]. On the job, the risk of liability is much greater. An employer will generally be held liable if an employee is negligent in his or her actions, but not necessarily for intentional violations unless the employer knew or “reasonably should have known” about them [22].

More particularly, employers may be found liable or guilty depending on the nature of the illegal actions by the employee, the employee’s role in the company, and the degrees of diligence given by an employer to prevent foreseeable illegal actions. For instance, if an employer failed to take certain precautions to prevent an employee from committing a violation that leads to leakage of customer financial information or health records, employers may be made a party in the complaint [22, 44]. Or, if an employer failed to perform an appropriate background check of a job candidate where the candidate had a history of harassment and, after hiring the candidate, the employee harassed others in the office or online, the employer may be found as having contributed to the offense [27, 57].

Again, to help reduce risk, it is extremely important to have in place and have communicated policies that govern employee online behavior related to the job. Interestingly, companies are also beginning to develop policies regarding financial dealings and behaviors off the job that pertain to company interests; however, this can invite an invasion of privacy suit and so the decision about these off-the-job policies should be weighed not only with legal counsel [27], but also in risk-mitigation activities (risk of potential exposure) if no policy is established [44]. Note, however, that some legal experts advise that if an offense is already prohibited by law, then it may be best not to create a policy about that issue because it might conflict with the interpretation of the law (raising further legal challenges), and unless all reasonable precautions are taken to prevent the violation, it might make the company culpable because it implies that an action was “foreseen” by the employer [24].

Instead, some legal experts suggest that in those cases where laws are extant, policies should simply state that employees must comply with the law. This decision must be carefully decided by the company attorneys and the human resources department. Furthermore, if policies are written governing “off the job” behavior or “virtual work” behavior, companies need to ensure due care and due diligence in taking all reasonable precautions to prevent violations while simultaneously crafting measures to help ensure the protection of individual privacy [44, 47].

In Focus

The difference in viewpoints about the number of policies a company creates turns on the issue of whether to try to cover as many bases as possible, realizing that someone might claim that a violation not covered by policy was exempt because it was not in an “exhaustive list,” or whether the minimalist approach may risk that someone might claim that management did not take sufficient steps to notify employees of what was acceptable. An attorney is in the best position to judge the lesser of the evils.

3.5.3 Corporate Espionage

In addition to threats from competitive intelligence gathering, and along with globalization and the growth of information and information value, corporate espionage has become easier and pervasive. Espionage, simply put, is a covert method of gathering information about a competitor or enemy. Espionage can lead to blackmail, extortion, defamation (character assassination), and sabotage. Techniques used to gather intelligence and commit corporate espionage can come from human intelligence (humint), signal intelligence (sigint), and image and photographic intelligence (imint).

Human intelligence may come from planted spies, from leakage of confidential information such as from picking through trash for sensitive documents (dumpster diving), and from providers of janitorial services who have access to buildings after hours. People may also reverse engineer technology to learn of trade secrets or steal proprietary information or methods. Signal intelligence is the interception of information as it moves over a communications channel, such as a telephone or a data communications network. Along with the typical video surveillance techniques, with technologies such as Google Earth, people can gather image intelligence about facilities.

Counterintelligence is the term applied to techniques used to prevent corporations from falling victim to intelligence gathering and espionage. Counterintelligence attempts to prevent unauthorized disclosure of proprietary information, detect espionage attempts, and define defensive operations. Sample counterintelligence techniques include document shredding, reviews of public statements and sales presentations to ensure that no proprietary information is disclosed, and ensuring that laptop computers and mobile devices use cryptography and strong authentication (to be discussed in more detail later).

TABLE 3.2 A Brief List of Historical Espionage (Adapted from Casey, 1996 [58]).

|

• Roman financial speculators and merchants financed and performed acts of espionage for the Roman intelligence service. • The Celts stole the secrets for making superior chariot wheels from the Romans. • Hannibal practiced the art of misinformation by having phoney “official” letters fall into enemy hands. • Julius Caesar used spies to learn the weaknesses of battlefield and political opponents. • Napoleon kept extensive background files on political rivals and suspected enemies. |

3.6 Forensics

Forensics involves all the activities in collecting and preserving evidence and answering questions for legal purposes [57]. There are many subcategories of forensics when it comes to information and computer security, which include digital forensics, computer forensics, and others. Forensics may range from a single intrusion from a hacker to systematic corporate espionage. In the latter case, a variety of forensic procedures are necessary and may uncover illicit human intelligence (humint), signal intelligence (sigint), and photographic and image intelligence (imint). For our final section of this chapter, we will address the broad and general legal aspects of forensics and evidence that managers should know about; we will return to forensic procedures and evidence gathering later, in the chapter on security operations.

3.6.1 What Constitutes Evidence?

Generally speaking, to be admissible in court, evidence must pass three tests: (1) It must be relevant to the crime or complaint, (2) it must be authentic, and (3) it must be reliable. Relevance can actually involve casting a wide net. For instance, all the data in a log may be relevant to a crime or a complaint even if the data do not come from the alleged attacker if the data provide contexts with which to interpret the crime or violation [16, 57]. Authenticity of evidence can be a much harder test to pass. For instance, because digital evidence can be altered, some form of “proof of authenticity” is required, which might include non-repudiation techniques or tracing the chain of custody of the information or materials [21]. A chain of custody consists of all the steps and handlers of the information or materials from origination to its delivery into proceedings. Reliability requires the “proof” that there were no errors in the generation or interpretation of the evidence—for instance, that an internet protocol (IP) address of a purported offender was not spoofed (forged) [19, 29].

3.6.2 Cyber Crime Evidence

Relative to evidence and cyber crime, there are two critical issues for managers to consider: gathering evidence and preserving evidence to present at trial. In the United States, the Fourth Amendment protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures, but a search or seizure is reasonable if it does not violate a presumed expectation of privacy [19, 21]. Beyond this basic facility, law enforcement and the courts must be involved in the collection of evidence for criminal prosecution and, in most cases, need a court order or a search warrant. If managers suspect criminal activity, it is important to involve the legal department and alert the relevant agencies. If the legal issues are in the nature of civil violations, the bar is set lower in terms of evidence collection and preservation because criminal law requires conviction if evidence is beyond a reasonable doubt, whereas in civil trials, only the lower standard of preponderance of evidence is needed for a favorable judgment. Nevertheless, in all cases of a suspected violation, managers need to coordinate their collection of evidence with legal counsel.

3.6.3 Cyber Law and Cyber Crime Issues

An example of a potential legal violation includes what is called cyber squatting. The U.S. Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (15 U.S.C. 1125) prohibits the registration of a domain name in bad faith (e.g., deception) by a third party. This protects those who hold a trademark or servicemark from cyber pirates (those who register a domain name associated with a trademark or service mark owned by another). It is important to realize that trademarks and servicemarks are given for specific uses (the codes and descriptions are available from the U.S. Patent Office website). No action should be taken unless it is clear that the use of the domain conflicts with the type of trade or service that was registered [42].

For instance, if a trademark was registered by a company called “CookiesRus” for software that installs electronic tracking cookies on a computer for marketing purposes, and a bakery registered a trademark called “CookiesRus” and wanted to register a mail order delivery service using that name, most likely there would be no conflict because these entities would have registered their trademarks or servicemarks under different trademark or service codes [21, 42]. Another example is the Communications Decency Act (47 U.S.C. 223), which stipulates that online service providers shall not be treated as publishers in terms of liability for defamatory postings made by others and may not be held liable for defamation in such cases. However, recent legal challenges may ultimately lead to changes in this stance.

In this chapter, we presented an overview of some legal issues confronting managers who are responsible for information security. We emphasized that managers should not act in the capacity of an attorney, but we also emphasized that they cannot afford to be ignorant of the law. Most of the legal concepts we broached in this chapter will be revisited in a more applied fashion in later chapters, such as those covering topics on operations and personnel management. We discussed security management and security policies, and we covered some of the legal aspects related to mobile and remote work. We introduced the concept of intellectual property and suggested that these assets should be classified in a risk assessment process. We stated that managers should know what is permissible regarding employee monitoring and presented those implications for personnel and security policies. Finally, we gave a quick survey of cyber crime and cyber law to enable a basic understanding of the legal aspects of forensic analysis and preservation of evidence, and we introduced the chain-of-custody concept. In the next chapter, we will rely on these foundations and consider regulations and governance.

Topic Questions

3.1: What are some of the key features of security management presented in this chapter?

3.2: What are some conditions mentioned in this chapter for when employers might be held liable for the actions of their employees?

3.3: Copyrights are____________, whereas patents are___________.

3.4: The Fourth Amendment provides U. S. citizens:

___ Freedom to carry arms

___ Freedom of speech

___ Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures

___ Freedom from self-incrimination

3.5: Espionage is:

___ Only applicable to the military and intelligence communities

___ A covert method of gathering information about a competitor or enemy

___ A crime that cannot be prosecuted if the perpetrators are in another country

___ A physical action that destroys property

3.6: The agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is overseen by the:

___ World Trade Organization (WTO)

___ Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

___ Internal Revenue Service (IRS)

___ U.S. Patent Office

3.7: A chain of custody consists of all the steps and handlers of the information or materials from origination to its delivery into proceedings.

___ True

___ False

3.8: Video surveillance is prohibited in businesses.

___ True

___ False

3.9: The U.S. Anti-Cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (15 U.S.C. 1125) prohibits:

___ Using email to request sale of a domain name

___ Registering more than one domain name

___ People from sending SPAM

___ The registration of a domain name in bad faith

3.10: Most copyrights end with the death of the author.

___ True

___ False

Questions for Further Study

Q3.1: Contrast the U.S. First Amendment Rights with privacy protections in the European Union (EU). For example, consider the Hague Convention on Jurisdiction and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial cases: www.hcch.net.

Q3.2: What are managerial responsibilities for protecting evidence in both criminal and civil incidents?

Q3.3: Explain where the line should be drawn between management’s legal responsibilities and those that should be left to the attorneys.

Q3.4: What are some key trends and changes in cyber crime since the early 2000s?

Q3.5: Investigate the U.S. Patent Office and summarize the various codes used in trademarking.

Defamation may result from posting false comments in newsgroups, blogs, or social media.

Discovery allows inspection access to certain information such as email by outside parties in a lawsuit.

Evidence must pass three tests to be admissible in court: (1) It must be relevant to the crime or complaint, (2) it must be authentic, and (3) it must be reliable.

ISR stands for Intelligence (gathered information), Surveillance (observation), and Reconnaissance (scouting for information).

Management is a function that includes planning, organizing, directing, and controlling organizational resources.

Patents are inventions to which the patent holder is granted exclusive use for a period of time by federal law.

Vulnerabilities represent the potential to exploit systems and information.

References

1. Coventry, W. F., & Burstiner, I. (1977). Management: A handbook. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

2. Meredith, J. R., & Mantel, S. J. (1995). Project management: A managerial approach. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

3. Denton, D. K., & Wisdom, B. L. (1992). Shared vision. In A. A. Thompson Jr., W. E. Fulmer, & A. J. Strickland III (Eds.), Readings in strategic management (pp. 52–56). Boston, MA: Irwin.

4. Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1993, March–April). Strategy as stretch and leverage. Harvard Business Review, pp. 75–85.

5. Mintzberg, H. (1994, January–February). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, pp. 107–114.

6. Semler, S. W. (1997). Systematic agreement: A theory of organizational alignment. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 8, 23–39.

7. Stacy, R. D. (1992). Managing the unknowable. Strategic boundaries between order and chaos in organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

8. Synnott, W. R. (1987). The information weapon: Winning customers and markets with technology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

9. Porter, M. E. (1979). How competitive forces shape strategy. New York, NY: Free Press.

10. Porter, M. E. (1996, November–December). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review, pp. 61–78.

11. Simon, M., & Houghton, S. M. (2003). The relationship between overconfidence and the introduction of risky products: Evidence from a field study. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 139–149.

12. Quinn, J. B. (1992). Managing strategic change. In A. A. Thompson Jr., W. E. Fulmer, & A. J. Strickland III (Eds.), Readings in strategic management, 4th ed., pp. 19–42). Boston, MA: Irwin. (Reprinted from Sloan Management Review, 21, 3–20.

13. Greer, C. R. (1995). Strategy and human resources. A general managerial perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

14. Burgleman, R. A., & Grove, A. S. (1996). Strategic dissonance. California Management Review, 38, 8–28.

15. Solomon, M. G., & Chapple, M. (2005). Information security illuminated. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

16. Purser, S. (2004). A practical guide to managing information security. Boston, MA: Artech House.

17. Newman, R. C. (2010). Computer security: Protecting digital resources. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

18. Himma, K. E. (2007). Internet security: Hacking, counterhacking, and society. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

19. Brenner, S. W. (2010). Cybercrime and the U.S. criminal justice system. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The handbook of technology management (pp. 693–703). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

20. Fischer, R. J., & Green, G. (1992). Introduction to security (pp. 122–157). Boston, MA: Butterworth-Hienemann.

21. Keck, R. (2005). Disruptive technologies and the evolution of the law. The Legal Brief, 23, 22–49.

22. Knudsen, K. H. (2010). Cyber law. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The handbook of technology management (pp. 704–716). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

23. Novosel v. Nationwide Insurance Company (1983). United States Court of appeals, Third Circuit 721 F.2d 894.

24. Sovereign, K. L. (1994). Personnel law. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

25. Van Zant, K. (1991). HR Law. Atlanta, GA: Gerber-Alley Press.

26. Martinko, M. J., Gundlach, M. J., & Douglas, S. C. (2002). Toward an integrative theory of counterproductive workplace behavior: A causal reasoning perspective. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10, 36–50.

27. Beadle, J. (2010). Corporate law and legal counsel: A mutually dependent relation. The Legal Brief, 15, 19–27.

28. Spinello, R. A. (2011). Cyberethics: Morality and law in cyberspace. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

29. Jenkins, J. A. (2011). The American courts. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

30. Gathegi, J., & Workman, M. (2009). Virtual work. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The handbook of technology management (pp. 279–288). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

31. People v. Zelinski, 155 Cal.Rptr. 575 (1979).

32. Swink, D. R. (2001). Telecommuter law: A new frontier in legal liability, American Business Law Journal, 38, 857.

33. Tonsing, M. (1999, July). Welcome to the digital danger zone: Say hello to the virtual workforce of the next millennium, Federal Lawyer, 46, 19.

34. Open Security Foundation (2010). AvMed Health Plans security breach: Lost or stolen laptops. Retrieved March 21, 2010, from http://datalossdb.org/incidents

35. Rosen, J. (2000). The unwanted gaze: The destruction of privacy in America. New York, NY: Random House.

36. Commonwealth v. Brion, 652 A.2d 287, 289 (Pa. 1994).

37. Workman, M., Bommer, W., & Straub, D. (2008). Security lapses and the omission of information security measures: An empirical test of the threat control model. Journal of Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 2799–2816.

38. Monitoring employee e-mail and internet usage: Avoiding the omniscient electronic sweatshop: Insights from Europe 2005. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law, 829.

39. Nichols, D. H. (2000). Window peeping in the workplace: A look into employee privacy in a technological era. William Mitchell Law Review, 27, 1587.

40. Northwest Airlines v. Local 2000, Civ. No. 00-08 (D. Minn. Jan. 4, 2000).

41. Ortega v. O’Connor, 480 U.S. 709 (1987).

42. Nydegger, C. (2010). In a legal sense or rather cents: Why nickel when you can dime your opponent to death? The Law and Legal Strategy Review, 19, 233–249.

43. Ryan, J. J. C. H. (2007). Plagiarism, education, and information security. IEEE Security & Privacy, 5, 62–65.

44. Nemeth, C. P. (2011). Law and evidence. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

45. Workman, H. R., & Nydegger, R. D. (2011). W/N scores big win in SCO v. Novell litigation. Salt Lake City, UT: Workman and Nydegger Attorneys at Law. Retrieved June 12, 2011, from http://www.wnlaw.com

46. Harvey, C. (2007, April). The boss has new technology to spy on you. Datamation, pp, 1–5.

47. Himma, K. E. (2010). Legal, social, and ethical issues of the Internet. In H. Bidgoli (Ed.), The handbook of technology management (pp. 753–775). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

48. Fairweather, B. N. (1999). Surveillance in employment: The case of teleworking. Journal of Business Ethics, 22, 39–49.

49. Scholz, J. T. (1997). Enforcement policy and corporate misconduct: The changing perspective of deterrence theory. Law and Contemporary Problems, 60, 153–268.

50. Borrull, A. L., & Oppenheim, C. (2004). Legal aspects of the Web. In B. Cronin (Ed), Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 38 (pp. 483–548). Medford, NJ: Information Today.

51. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. (1992). Transportation implications of telecommuting. Washington, DC: National Transportation Association. Retrieved July 12, 2010, from http://ntl.bts.gov/DOCS/telecommute.html

52. Losey, R. C. (1998). The electronic communications privacy act: United States Code. Orlando, FL: The Information Law Web. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from http://floridalawfirm.com/privacy.html

53. Braithwaite, J., & Drahos, P. (2000). Global business regulation. New York, NY: Cambride University Press.

54. Kadrich, M. (2010). Does privacy exist in the age of social networking? ISSA Journal, 8, 18–21.

55. Akdeniz, Y., Walker, C., & Wall, D. (2000). The Internet, law, and society. Harlow, UK: Pearson Publishing.

56. Milwaukee News (2009). Nurses fired over cell phone photos of patient: Case referred to FBI for possible HIPAA violations. Retrieved July 15, 2010, from: http://www.wisn.com/news/18796315/detail.html

57. Grama, J. L. (2011). Legal issues in information security. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

58. Casey, M. S. (1996). Corporate intelligence: Information gathering and corporate espionage. Cambridge, MA: Harcourt Press.