Managing Organizations Securely |

CHAPTER6 |

IN THIS CHAPTER, WE WILL devote some time to reviewing some of what we covered thus far, and then present security management concerns and cover organizational impacts, both positive and negative. In preparation for moving on to more technical content, we will visit some of the issues related to security contravention and security omission. We will distinguish between insider and outsider threats and discuss monitoring. In line with the knowledge scaffolding approach we have taken in this textbook, we will briefly summarize highlights from Section 1 to reinforce learning, and we will provide a preview of things to come.

Chapter 6 Topics

This chapter:

• Provides an overview of information architecture.

• Reviews security policies and security models and their relationships.

• Discusses security stances.

• Discusses risk management and risk assessment in relation to security countermeasures.

• Describes monitoring, information collection, and handling of incidents.

• Explains organizational impacts from monitoring.

Chapter 6 Goals_

When you finish this chapter, you should:

![]() Be able to describe the layered aspects of information architecture and describe the relationships to information security.

Be able to describe the layered aspects of information architecture and describe the relationships to information security.

![]() Be able to explain security management in a security policy context.

Be able to explain security management in a security policy context.

![]() Know what countermeasures are and how they are used.

Know what countermeasures are and how they are used.

![]() Understand key critical issues related to security standards and policies.

Understand key critical issues related to security standards and policies.

![]() Be able to discuss the issues related to employee monitoring and surveillance.

Be able to discuss the issues related to employee monitoring and surveillance.

6.1 Security Management Overview

A primary role for managers as far as security is concerned is to provide well-defined means of identifying, monitoring, mitigating, and managing security risks. This involves oversight of members in the organization who are responsible for taking security-related actions. Viewed traditionally, it may seem as though security is only a technological problem by the concentration on techniques and technologies for creating better defenses and using criteria in performing risk analyses and the application of security countermeasures, but it is important to note that security is mainly a behavioral issue.

Along those lines, an important consideration is that businesses are dynamic, as are the environments in which they operate, and organizations are on an evolutionary path. To illustrate, organizational theory from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s saw the rise of socio-technical systems management. In this era, the importance of creativity was recognized. Organizations were viewed as strategically behaving entities, and workers were viewed as part of a larger system in which systematic alignment between inputs and outputs was seen as crucial in maintaining a well-oiled organizational machine. From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, organizations evolved through the view of the general systems theory of management. The concept of systematic organization as a well-oiled machine was supplanted by the view of the systemic organization. Complexity, interconnectedness, and globalization generated emphasis on organizations as “epiorganisms”— functioning economic systems that were organic and interactive.

Since the early 2000s, we have witnessed a paradigm shift toward reconstructivist management view. This theory presumes that self-organizing and emergent forces shape work, and workers lead in self-development and the humanization of work, taking active roles in reconstructing organizations as parts of global societies. After several scandals, such as the one at Enron, and corporate “bailout” controversies, there has been a renewed emphasis on ethics and social responsibility; budding ethical tenants also create struggles in managing organizations securely. Incorporating all of the administrative, procedural, technological, and human resource elements of security management, we will now take a broad survey of how these interactions affect security behaviors to conclude Section 1.

6.1.1 Information and Systems Security Infrastructure

Looking back on what we have covered thus far, we understand that security management strives for the reduction of risk exposure by using the processes of threat identification, asset measurement, control, and minimization of losses associated with threats. Managers often survey and classify assets, conduct security reviews, perform risk analyses, evaluate and select information security technologies, perform cost/benefit analyses, and test security effectiveness.

This is accompanied by the development of policies, comparisons against standards, procedures, and guidelines; all of these activities help managers to ensure information CIA: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. To classify assets and information, to identify threats and vulnerabilities, and to help ensure that effective countermeasures are implemented, there are a variety of tools available to managers including information classification systems, configuration management and change controls, and employee security training. Considering all of these organizational security aspects, it is easy to see how complicated managing security can be, especially considering that a company’s information systems infrastructure comprises all the resources and assets and efforts related to information and the computing facilities used by people in organizations for decision making and action taking.

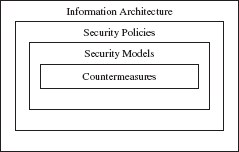

We know that an organization’s information and systems security infrastructure supports the organizational mission and objectives by helping to ensure CIA. Under the umbrella of information infrastructure resides information architecture, which consists of how information and systems are organized within a company and between trading partners; therefore the information architecture outlines all the facilities that must be secured. Security policies, as we have learned, are the rules used to maintain organizational security, as well as for monitoring and reporting in the case of security breaches.

Security models are methods and techniques policies might dictate, such as what privileges are allocated for which resource and to whom. Finally, countermeasures are the specific implementations or technologies used in protecting the CIA of the information architecture, and procedures are how countermeasures are carried out. Figure 6.1 highlights these layered relationships.

FIGURE 6.1

Layered security relationships.

6.1.2 Information Assets: Classification and Architecture

A main element in attending to information security is to know what information is maintained by the organization, where the information is located, and how the information is “classified,” such as company confidential or proprietary. As previously noted, ISO/IEC 17799 and ISO/IEC 27002 are examples of classification systems and criteria. Classification is an important component in carrying out security policies, especially in relation to the rules for implementing controls that determine who has what access rights to various resources. This is necessary to ensure that only those who are authorized are able to gain the proper access. Managers can then specify in procedure manuals or other documents what technologies and techniques (countermeasures) to use to ensure this.

Architecture in a classic sense is visualized in blueprints for how a structure is organized along with its amenities or features. Information architecture similarly contains the specifications, diagrams, designs, requirements, documentation, topologies, and all the schematics that illustrate the information and computing resources used by an organization. Its function is to create and communicate the “information environment” including aesthetics, structure, and mechanics involved in organizing and facilitating information ease of use, integrity, access, and usefulness [1].

Information architecture is divided into macro- and micro-levels. For example, architecture for a web-based application on a macro-level would illustrate all of the intersections and distributions of the information storages and flows through the consumer–producer (value) chain including those among trading partners, company locations, co-locations, and agencies in which the organization corresponds such as between airlines and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or banks and the Federal Reserve. On the other hand, architecture for a web-based application on a micro-level would illustrate the individual components within a system or a collection of systems. It might show how software and systems are partitioned, where the network access points are located, and which components are centralized and which are distributed; it might even specify some of the key technologies that would constrain the architecture to a type of platform or software system.

6.1.3 Security Policies and Models

As we have discussed, among the primary tools for managers are security policies. Because security policies define how information and systems assets are to be used and governed, they differ somewhat from other organizational policies. Security policies are either documents that establish the rules and punitive sanctions regarding security behaviors (for instance, they may dictate that users must change their passwords monthly) or they consist of facilities that are codified into information and communications systems that define the rules and permissions for system operations. For example, a router’s security policy may permit only egress ICMP messages and deny all those that are ingress, or a host computer’s security policy may prohibit files from copying themselves, or from accessing an email address book, or from making modifications to the Microsoft Windows Registry (more about these technical details in Section 6.2).

Security policies are not just written documents for human consumers. They can be electronically implemented in computer systems to automatically govern system usage and behavior.

Some security policies define security models. For example, the Clark and Wilson model states that systems must prevent tampering from unauthorized users; that file changes must be logged; and that the integrity of data must be maintained and kept in a consistent state. A countermeasure is the specification for an implementation of a security procedure or technology to address vulnerabilities, and countermeasures are often dictated by security models. For example, if we applied the Clark and Wilson model to a human process such as “payroll,” the model would specify that someone in an authorized role, such as the CFO, must approve and record the distribution of the payroll checks cut by the accounting department. A countermeasure that implements the Clark and Wilson model may include computer transaction monitors such as Tuxedo, CICS, and Open/OLTP.

The Clark and Wilson model is therefore transaction-oriented, and an electronic transaction is defined by ACID properties, for (1) atomicity—a discrete unit of work, where all of the transactions must be completed or committed to databases simultaneously, or rolled back until it can be committed, (2) consistency—where data must transition in an orderly manner from the beginning of the transaction to the end of the transaction, (3) isolation—where the transaction is self-contained and not reliant on any other transactions for its operations, and (4) durable—meaning the data remain in a consistent state until they are intentionally changed [2].

An essential concept in transactional security models such as Clark and Wilson is that operations must be well formed. A well-formed transaction occurs in a specific authorized sequence, which is monitored and logged. Logging is often done to an audit file, or computer program changes are typically logged to a change control log. Logs allow auditors, administrators, and managers to review the transactions to ensure that only authorized and correct changes were made. Besides transaction monitors, many companies use change control applications and system configuration management (SCM) systems for these purposes.

In Focus

There are other security models such as state machines and access matrices, and many of these models are used in combination. Security models attend to different aspects of the information system security infrastructure, such as the confidentiality and/or integrity of the information among disparate systems and users in various roles. At the most basic level, security models define read, write, and execute permissions for “objects” and how these are allocated to “subjects,” whether they are human processes or implemented in operating systems and software applications.

6.1.4 Stances and Countermeasures

A security model may specify security stances. Stances are primarily affected by the countermeasures that control the flow of information and managing what subjects (e.g., people or processes) can have what kind of access to objects (e.g., resources, data, or programs). Stances can be optimistic, where that which is not explicitly denied is permitted, or pessimistic, where that which is not explicitly permitted is denied. Consider, for example, that a network administrator may set a network router to permit all Internet connections unless he or she specifically creates a rule to block those named—this is an optimistic stance.

There will be combinations of stances at different points in the systems and networks in the infrastructure. For example, an optimistic security stance may be taken to allow traffic to a web server, and a pessimistic stance taken to permit only a given proxy system to access an internal domain name service (DNS). Fundamentally, in addition to resource access, stances deal with the rules that guide procedures for access rights, for instance, granting read, write, and execute permissions to an owner or creator of a file, but not to anyone else.

An example of an information flow security stance model is the Bell and LaPadula. This model (among other things) defines who is privileged to access what, in an effort to help ensure information confidentiality. In its original form, as shown in Figure 6.2, it was designed for the intelligence community to specify who could access information based on their security clearance levels. If we applied this model to a human process such as the production of company confidential planning documents, it would specify that no one outside the company may be given a copy of them. Technologically, we see the countermeasures implemented in computer operating systems as file system permissions and as access control lists.

Another information flow security stance model is the Biba model. This approach is similar to Bell–LaPadula, but it goes beyond addressing confidentiality by also attempting to protect the integrity of data by prohibiting unauthorized persons from making modifications to data to which they have only read access. Countermeasures using the Biba model include access controls (including biometrics; more on this later in the chapter) and authentication to ensure authorized access and to dictate that an authorized user-level process may not exceed its privileges to modify a file unless specifically granted—for example, through the Windows “Executive” security access module, or the authorized grant of escalated privileges using the “setuid” capability in the UNIX operating system, which allows a user-level program to gain access to “superuser” or “root” (administrator) operating system–level functions.

FIGURE 6.2

Illustration of the Bell–LaPadula model.

Unfortunately, as we will see later, the UNIX setuid capability can also become a source of security threats by gaining unauthorized access to privileged system functions or by illicitly escalating privileges.

As seen, then, ways to deal with threats involve implementing countermeasures. Countermeasures consist of physical, technical, administrative, and behavioral techniques. Physical countermeasures are those that have a tangible presence, such as a fireproof storage vault. Technical countermeasures are those that involve some software system or application such as a virus scanner. Administrative countermeasures are those that involve procedures, such as having employees sign non-disclosure agreements or using checklists to ensure compliance with a standard. Behavioral countermeasures are those that involve “humans in the loop,” such as ensuring the administrator deletes login accounts that belonged to terminated employees [3].

6.2 Risk Assessment and Management

Obviously, information systems are critical assets in most organizations, and protecting them is essential in corporate and governmental operations, yet no system can be completely secure, and determined attackers can breach even the hardest of defenses. Managers must be prepared to define the level of risk that they are willing to accept compared to the costs associated with implementing preventive and corrective measures. As we presented in the previous chapter, risk assessment is an ongoing process of identifying risks and threats, whereas risk management is the ongoing process of implementing measures according to the costs and benefits associated with risks and security countermeasures, as well as determining containment and recovery strategies and measures for attacks when they occur.

In Chapter 5, we also presented the idea that that managers, through their administrative practices, strive to mitigate risk, or take preventive measures to reduce them. Managers also try to avoid risks by placing constraints on what people do or what they implement, where they implement countermeasures, and when, and most particularly, what not to implement. Managers may also choose to accept some level of risk because the costs or time to implement precautions are not worth the benefits. We also presented the notion of risk transference, which involves placing the onus or risk burden on another in exchange for a fee (for example, having insurance) or by exclusions in a contract, such as indemnification clauses. In this section, we will present technological countermeasures to help managers manage securely.

6.2.1 Risks and Countermeasures

We have covered some of the techniques used in the ongoing process of risk assessment, such as conducting inventories, classifying information, attempting to determine vulnerabilities, and so forth. As these functions are done, part of assessing risk includes determining how proactive versus reactive to be as an economic tradeoff when it comes to security countermeasures. To try to illustrate this idea, a manager may spend 15 percent of his or her budget to prevent access of HIPAA-regulated data (i.e., medical patient information), but perhaps he or she is willing to spend only 5 percent of his or her budget to protect sales report data, with consideration for the expenditures in mind if a security breach occurs after the fact.

Some guidelines in the security literature suggest using a formula denoted ALE for annualized loss expectancy, which is a function of the cost of a single loss expectancy (SLE), or the cost to deal with the loss of a given compromised asset, multiplied by the annualized rate of the loss for each potential occurrence (ARL) [4]. Other financial formulas that are often used include payback periods on depreciated loss of assets and expected future value with time value of money for replacement costs from a loss. However, although certainly helpful, these quantitative financial assessments overlook important qualitative components that should also be considered, such as damage to company reputation from a security breach [5]. Moreover, even the quantitative measures rely on some amount of subjectivity and guesswork.

In Focus

It is important that managers involve the finance and accounting departments before making financial declarations to help avoid discrepancies that may arise during an audit.

The key to determining risk is a blend of quantitative (often statistical) assessments and logical evaluations, and just plain good judgment—and managers are paid as much for their judgments as any other aspect of their job. Therefore, because countermeasures are designed to prevent a security breach and their assessed value according to the total impact, both quantitative assessments (such as ALE) and the qualitative judgments of managers (such as following normative rules) are necessary for successfully managing security.

Countermeasures are actions that implement the spirit of security policies and are designed to address vulnerabilities. Where a security policy might call for the use of role-based access controls (RBAC) for a particular business function, such as “cut checks for payroll,” an example of a countermeasure in computer security may be to utilize a particular access control list (ACL) maintained with a directory service, such as Microsoft’s Active Directory. The vulnerability this may address is to prevent unauthorized access to payroll files and control who is allowed to cut checks. Or a countermeasure may call for the use of a transaction management system, such as Tuxedo. The vulnerability this might address is to prevent data inconsistency and preserve data integrity by ensuring a completed two-phased commit between processes and distributed databases involving an update to a hospital patient medical record (Figure 6.3). In this latter example, the transaction manager issues to each database a request to update (called a pre-commit); if the database can lock the data and allow the update, it will return an acknowledgment to the transaction manager. If all of the databases return positive acknowledgments, the transaction manager will commit all of the data updates simultaneously; otherwise it will do a rollback and try again.

FIGURE 6.3

Two-phased commit for a patient record.

Other countermeasures might consist of implementations of cryptography—ranging from encrypting a message using PGP before sending it through email, to the authentication of users with Kerberos. Cryptography is also used in creating message digests (such as MD5) to ensure that there has been no tampering with data and in creating digital signatures for non-repudiation. We will explore the technical aspects involved in counter-measures in Section 6.3.

Security controls that are used in countermeasures must allow people to work efficiently and effectively; therefore, countermeasures must enable maximum control with minimum constraints. This aspect relates to ensuring resource availability to legitimate workers. Managers have to contemplate the consequences of security actions; however, in modern organizations, successful work typically means successful teamwork and open communications where information must be able to pass through organizational barriers for work to be done efficiently and effectively, and also to ensure effective security operations.

This important element was described by Sine et al. [6] as organic organizational capabilities that enable company adaptation and agility. Yet all the efforts to compartmentalize and quarantine people for security purposes work against these core organic principles. Thus, strict approaches to security such as separation of duties and compartmentalization should be confined to only those most sensitive operations, functions, and roles in the company.

In Focus

Most organizations strive to thin the boundaries between organizational units in order to improve visibility of operations and communications, and to facilitate problem solving (including solving security problems). However, certain government agencies and companies doing secure work such as Northrop Grumman, Harris Corporation, or Unisys are perhaps more inclined than an average organization to use stringent security measures in organizational controls, especially in certain departments.

6.2.2 Hoping for the Best, Planning for the Worst

Managers, of course, hope that their proactive attempts to protect the organizational resources and personnel will be successful, but they also must consider the worst-case scenarios. Risk management, as we have discussed, is the process that addresses threats and their associated costs and planning for contingencies. Contingency planning may often involve the development of “what if” disaster scenarios, and popular techniques for this range from Delphi, which is a group decision-making process in which participants provide anonymous input and ideas that are evaluated by the group—or computerized stochastic modeling, which produces statistical probabilities about possible outcomes based on information solicited from people or derived from technology queries in data mining or from expert systems.

Contingency planning includes a disaster recovery planning process in which alternative means of information processing and recovery (if a disaster occurs) are devised. This process produces a business continuity plan, which outlines how the businesses are to continue to operate in the case of a disaster—manmade or natural [4]. Managers also need to consider what to do after a disaster happens and how to recover from it.

A recovery plan concentrates on how to restore normal operations. These plans may include using a disaster recovery center, where equipment is kept and personnel are sent in such an event. There are companies such as SunGard that specifically provide these services. Another important process is facilities management, which incorporates procedures for dealing with disasters such as using offsite backup and storage facilities, distributed operations and monitoring centers, and self-healing systems.

As presented earlier, there are many standards; for example, those devised by the National Computer Security Center (NCSC), which is part of the National Security Agency (NSA), are specifically geared toward the government or makers of systems for government consumers. The NCSC conducts security evaluations and audits under the Trusted Product Evaluation Program (TPEP), which tests commercial applications against a set of security compliance criteria. In 1983, the NCSC issued the Department of Defense (DoD) Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria (TCSEC), which has become one of the standards for security compliance for these kinds of systems.

The TCSEC defines the concepts of subjects and objects within a security framework. Subjects fall into two categories: (1) direct surrogates for a user, which are applications or components that represent a human being or human action, or (2) internal subjects, which consist of those components or objects that provide services for other subjects, such as software applications or operating system features. Objects in this case are the instruments, applications, software, information, and other resources that subjects use or manipulate during the course of carrying out their duties. These standards rely on the notion of “trust,” and trust from a security perspective has a specific connotation. The concept of trust in an information security context is a system that is attack resistant and reflects the ability of a system to protect its information and resource integrity. The failure of a trusted system may compromise the entire security infrastructure, and so trust is a crucial concept [7].

6.2.3 Trusted Computing Base Versus Common Criteria

Early evaluation criteria based on the notion of trust included what is commonly referred to as the orange book, which defines a trusted computing base (TCB), and attempted to establish a base level of trust. The TCB was intended to comprise the entirety of protections including the roles and actions of users for a computing system, including hardware, firmware, databases, file systems, and software, and the combination responsible for enforcing security. The TCB criteria are denoted as (1) minimal protection (class D), (2) discretionary protection (class C), (3) mandatory protection (class B), and (4) verified protection (class A).

Each of these classifications includes subcategories of trust. For example, the C1 level calls for the separation of duties, particularly in terms of users and information. Among its requirements are the identification of information and the authorizations to access it. To achieve C1, access control lists (ACLs) must be used in addition to login controls. Also, there must be insulation between user and administrative or “system” modes of operations. The C2 level extends the requirements for C1 to include a requirement for auditing, among other things.

In Focus

When codified into systems, security policies can dictate which actions are permitted and which ones are denied, according to roles or permissions assigned to a user. Role-based entities and permissions may also work in conjunction with a directory service. One example is a version control system that can be used to manage access to documents as well as source code. In some configurations, a directory service such as the lightweight directory access protocol, or LDAP, or the Microsoft Active Directory, can be used to manage access to information and resources.

The TCSEC orange book—at least in terms of the vernacular used in the criteria—is applicable primarily to government and military systems. Industry tends to have different needs and often has different trust requirements. For instance, the TCSEC tends to leave out criteria that are concerned with the availability of systems and specify only weak controls for integrity and authenticity actions. Moreover, the TCSEC is mainly concerned with host computers and leaves void many of the important aspects of network security— especially in the context of the Web. The trusted network interpretation (TNI), also called the red book, was thus devised to help compensate for some of these gaps by including criteria for local area and wide area networks.

Whereas early computer systems, such as the Digital Equipment VAX running the VMS operating system, were evaluated according to the TCSEC, globalization has forced national or regional standards bodies to cooperate on standards criteria. Consequently, the International Standards Organization (ISO) created specification 15408, or what has become known as Common Criteria. The Common Criteria supplanted the TCSEC, as well as the Canadian Trusted Computer Product Evaluation Criteria (CTCPEC) and the European Information Technology Security Evaluation Criteria (ITSEC), among others.

The Common Criteria has several parts, but among the most important is the Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA), which is an agreement among participating countries to accept the criteria and recognize the audit results from evaluations regardless of which auditing entity (called signatories) performed the evaluation. U.S. signatories, such as the National Security Agency (NSA) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), work with the National Information Assurance Partnership (NIAP) and have developed an informal standard called the Common Criteria Evaluation and Validation Scheme (CCEVS). CCEVS summarizes all the standards used by the United States in order to conform to the Common Criteria.

6.2.4 Evaluation and Certification

Systems sold to or used by government agencies are measured by various criteria (depending on the agency). In addition to the TCB and Common Criteria, there are myriad other standards and criteria that may need to be considered, as indicated in previous chapters. For commercial (non-governmental) applications, the important points for managers to know are that standards may provide some good guidelines for large organizations in terms of security assurance of systems and networks, as well as for developing security policies and conducting information assessments of risk. For instance, ISO 13355 provides guidelines for risk management processes.

However, if an organization is a government agency, or is federally regulated, it will probably require a formal certification and accreditation (called C&A) as part of the overall security policy. A certification is a comprehensive evaluation of an information system and its infrastructure to ensure that it complies with federal standards, such as the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA). An accreditation is the result of an audit conducted by a signatory or accrediting body, such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which gives the “go ahead” to put into production a certified system. Signatory auditors may give one of four accreditation levels ranging from low security to high security. Auditors will use various methods depending on which agency is doing the certification and who the consumers will be [3].

Even the best-laid plans can fail, so managers spend a significant amount of time pondering and trying to balance the security risks against other important organizational needs. The problem is that there are wide-ranging risks that cannot be foreseen, and not only are they human-induced, but they also come from natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods.

In Focus

After a major hurricane hit the Florida operations center for a large transaction processing firm, engineers from the organization flew to their SunGard site in Pennsylvania, where hot standby systems were at the ready, and the company resumed operations within 24 hours of the disaster. However, one should take into account whether, in the event of a disaster, critical personnel will be able to get to these backup centers. Consider, for example, that airlines were grounded during the 9/11 attacks in the United States—how would personnel get to the standby site if one could not fly?

A difficulty presented to managers is that security technologies and infrastructure, as an overhead (non-revenue generating) cost of doing business, has grown to a sizable amount of the average company’s budget. As noted earlier, security initiatives consume about 8 percent of the average company’s budget. Although it is important that security countermeasures be implemented to protect against what might involve much greater financial costs related to a security breach, they need to be commensurate [8].

To highlight this escalating issue, private industry spending on information security in the United States increased to more than $1 billion and surpassed $6.5 billion in the U.S. government, and spending has continued to rise steadily [9]. That is important to note when one considers that these costs provide zero contribution to the corporate profit margin; they are pure overhead expenses to the company along with opportunity costs. Consequently, there is an entire burgeoning field in preparedness and recovery with special emphasis placed on building cost-effective “smart, sustainable, and resilient” infrastructure [10].

6.3 Monitoring and Security Policies

Because of the costs and implications of security breaches to organizations, managers are striving to be more proactive in their security implementations. Among these techniques are the creation of security and incident response teams, increasing the provision for security training, the development of policies, and the implementation of physical and electronic countermeasures. Among the latest approaches finding its way into the security arsenal is the use of employee surveillance and monitoring. Although there are benefits to this practice, there are also many issues to consider including laws and the impact on human resources and performance [11, 12].

It is one thing to put in place countermeasures to try to prevent security breaches, and another to follow up after the fact. Employee surveillance (which we will include under various forms of monitoring) is on the rise to try to intervene in the middle as behavioral conduct unfolds real time. Monitoring is the physical or electronic observation of someone’s activities and behavior [13]—including monitoring email, observing web browsing, listening in on telephone conversations (such as for “quality assurance purposes”), and video recording employee movements and actions.

Surveillance laws and regulations differ by country, as we indicated earlier in the chapters on laws and governance. Many countries in Europe and the United Kingdom, for example, have stringent privacy laws, as noted. In the United States, privacy has been guarded under the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, but was weakened by the Patriot Act. Moreover, privacy in a legal sense generally pertains to those places and occasions where people have an expectation of privacy, which, for the most part, excludes public places and many areas within an organization.

Generally speaking, in the United States, common law (also called case law because it is created as cases are decided) stipulates privacy torts that have been used as grounds for lawsuits against organizations, such as intrusions into seclusion, which involves invading one’s private space, and public disclosure of private facts (private facts do not include public records) [14]. In the United States, there are differences among state laws in terms of what constitutes privacy; where some states such as Arizona, California, and Florida have in their constitutions a right to privacy clause, many other states do not [15].

6.3.1 Monitoring as a Policy

Managers carry special responsibilities for stewardship over personnel and organizational resources through enforcement of company policies and practices. In the execution of their stewardship, they may be involved in the gathering of information about employees such as their performance measurements compared to their objectives and other work-related activities; but also, increasingly, managers are called upon to gather information about and enforce organizational policies that include various security practices such as monitoring access to vital corporate resources [16].

To try to head off security breaches and improve prosecutorial ability, managers are implementing employee surveillance with increasing frequency. Employers generally have the right to monitor employees and their information and anything they have or do that is in “plain sight.” They also have the right to monitor information stored on their assets and to determine how these assets are accessed and used. Note that there may be legal restrictions that apply to listening in on telephone conversations or monitoring information in transit from one place to another—which can be subject to wiretap laws in the United States. Nevertheless, undoubtedly, the phrase “This call may be monitored for quality assurance and training purposes” has been heard by anyone who has called a customer service center or a technical support department. Why do they say this? Partly, it is to notify both the caller and the customer service agent that the call might be recorded as a way to deal with restrictions from wiretap laws that prohibit such activities [15].

A survey conducted by Harvey [17] indicated that managers regularly monitored employee web surfing. More than half reviewed email messages and examined employees’ computer files, and roughly one-third tracked content, keystrokes, and time spent at the computer. In addition, employers are increasingly adding video monitoring to their monitoring repertoire [18]. Of companies surveyed [17], only 18 percent of the companies used video monitoring in 2001, but by 2005, that number had climbed to 51 percent, and 10 percent of the respondents indicated that cameras were installed specifically to track job performance. Although the trend toward increased surveillance helps in prosecution after the fact, it has had little effect on prevention according to research [13, 19].

If a monitoring approach to security is used, it should be outlined in security and human resource policies and employment agreements; employees (and anyone who is monitored, including customers) should be notified. For legal purposes, as we stated before, security policies must be both enforceable and enforced, so there are particular elements of these legal issues to which managers must attend. Enforceability is partly a contractual matter, and for that reason, the corporate legal and human resources departments must be involved in the drafting of security policy documents regarding monitoring and surveillance, especially if security practices include telephone or video monitoring (surveillance) of employees.

6.3.2 Information Collection and Storage

Collecting information about employees has been viewed as important to perform three major functions: (1) credentialing for the purpose of allocating access rights to physical and/or virtual locations and resources, (2) the collection and distribution of data about employees, their demographics, physical characteristics (biometrics), and their travels and actions, and (3) surveillance, which is the physical or electronic observation of someones activities and behavior. These three elements are broadly focused on identifying employees and ensuring that only authorized persons have access to only those locations and resources to which they are authorized. The storage of surveillance and monitoring information is subject to a completely separate set of laws and regulations—and those are according to industry and purpose.

Because this is a tricky and an emerging area of law, it is extremely important to have any monitoring or surveillance measures or policies examined by the human resources department and reviewed by legal counsel before they are implemented. Not only are federal and state regulations involved, there are employment laws and statutes to be considered. On the other hand, employers may be compelled by law or regulation to monitor employees and/or information. There are times when managers can be ordered to conduct surveillance of some activity by court order.

Given the range of data collected by organizations, and the many laws and regulations involved, at this point, we will raise the idea that dealing with a breach of security such as an intrusion into a computer system by a hacker may require taking certain legal steps. If a manager ends up in a situation where he or she has to be involved in litigation, or must comply with a court order served by law enforcement, he or she needs to be prepared to present admissible evidence [14]. Computer logs and email are often not admissible by themselves without non-repudiation techniques. Non-repudiation involves generating a message digest such that a sender cannot deny sending a message, and a receiver cannot deny receiving it.

Next, the impromptu means of monitoring that managers have to work with, such as call monitoring, are not typically disconcerting to an outsider (such as a customer), but employees often report that they feel overly scrutinized by call monitoring. Indeed, such monitoring implies that everyone is potentially guilty of a crime [20]. This can have negative effects on positive organizational behaviors such as cooperation and information sharing. However, managers can help mitigate this concern by ensuring the preservation of organizational procedural justice—which is the perceived fairness in the process and the ability to have one’s concerns addressed along with having an avenue for escalation of concerns.

In Focus

Many organizations create a position called ombudsman; this person acts as a trusted intermediary between a complainant and the organization.

6.3.3 Monitoring and Organizational Justice

This point bears repeating, especially relative to surveillance: Managers should not draft security surveillance policies without legal advice. This is because, as with policies in general, security policies carry certain legal constraints and managers may even be held personally liable. Some of these constraints fall under employment law; in other cases, laws and regulations influence or determine such policies [14]. There are also laws that govern how you enforce a policy, such as how a manager (and his or her company) can monitor employees and their information.

We have suggested that enforcement of security policies needs to be offset with the concept of organizational procedural justice. Procedural justice is perceived when the process used to make the decision is deemed fair. There are a number of conditions that lead people to perceive justice in the process. First, people want to be able to have a say or voice in any decision that might affect them. Furthermore, people want to know that managers and those with power in the organization are suspending their personal biases and motivations from decisions and are relying on objective data to the greatest possible extent. Finally, procedural justice is perceived when people are presented with a mechanism for correcting perceived errors or poor decisions, such as having an appeal process.

We might consider our behavior more carefully when we know we are being recorded. In many cases, however, people do not stop and think about the many cameras that cover traffic on highways or those that are on walkways used by law enforcement to observe and record the actions of people, because these devices are blended into the landscape. However, in most cases in organizations, it is recommended (if not required) that managers inform employees of surveillance monitoring. To gain compliance with these policies, fear appeals are often used by managers as justification for conducting surveillance of employees. As technologies become cheaper, less obtrusive, and more sophisticated, there is a growing use of both overt and covert surveillance of employees, as we noted earlier. Also worth considering is that the range and the intensity of monitoring and surveillance has expanded along two axes: first, to try to determine patterns of behaviors associated with certain characteristics (some refer to this as profiling), and second, to reduce risks associated with potential harm and/or liability to individuals and companies.

D’Urso [19] reported that as many as 80 percent of organizations now routinely use some form of electronic surveillance of employees. Vehicles, cellular phones, computers, even the consumption of electricity have become tools for monitoring people and their activities. In the workplace, employers often use video, audio, and electronic surveillance; perform physical and psychological testing, including pre-employment testing, drug-testing, collecting DNA data, and conducting searches of employees and their property; and collecting, using, and disclosing workers’ personal information including biometrics.

To a degree, the use of security measures and surveillance lends to employees’ general perceptions of security, but there is a point at which security measures and surveillance psychologically undermine the perceptions of security as one is, or may be, increasingly placed under scrutiny, which can affect behaviors in unintended ways [21]. At a minimum, people may repress and internalize the emotional impact of the simultaneous effects of feeling under constant threat and under constant scrutiny. Studies have shown that such persistent stress conditions may lead to as much as half of all clinical diagnoses of depression, and ongoing research shows that placing people in a continuous fearful state can permanently alter the neurological circuitry in the brain that controls emotions, and this can exaggerate later responses to stress [22].

Research [23] has shown that employee monitoring can instill a feeling of distrust, and when people don’t feel trusted, they in turn tend to be untrusting, which can create a climate of fear and trepidation. In addition, imposing many monitoring policies can cause a mechanistic organizational environment where people will only perform tasks that are well defined, which limits initiative and creativity and leads to information withholding and a lack of cooperation. If a manager is not careful in considering all sides and viewpoints of the surveillance spectrum, he or she might lead the organization to self-destruction; at a minimum, surveillance can lead to increased employee absenteeism, but it can also lead to legal claims against an employer for emotional distress, harassment, or duress.

In Focus

Circularly, maladaptive social coping responses lead to increased fear, which leads to increased monitoring and surveillance, further elevating maladaptive social coping responses.

6.3.4 Surveillance and Trust

Even the most ardent applied behaviorist must acknowledge that people’s psychological states lead to how they behave. An important example regarding our subject matter is related to the psychological state of trust versus distrust. Trust is developed over time, and it is largely based on a consistency in meeting mutual expectations, such as keeping confidences (i.e., avoiding betrayal) and reciprocity.

In an organizational setting, this sort of trust develops between managers and employees in a rather awkward way, because managers hold reward and punishment power over their subordinates. In this manner, employees add the perception of benevolence of their managers to their perceptions that influence trust. The extent to which employee expectations of what the organization will provide and what they owe the organization in return (reciprocity) forms the basis of what is called a psychological contract. A psychological contract is maintained so long as there is trust between the parties. There are significant relationships between a psychological contract breach and negative work-related outcomes, ranging from poor performance to sabotage.

In terms of information gathering and surveillance, the psychological contract suggests that employees expect that espoused security threats by managers are real and the monitoring of their activities are justified, and that managers will act with due care and due diligence to protect the information gathered about employees and use the information for good purposes. Because the psychological contract involves trust, and because trust is influenced by perceptions of organizational justice, the mitigation for the negative effects of surveillance relies on managers ensuring procedural justice and fostering trust in the organization.

To sum up, when people perceive that they have control over their behavior, they tend to be more responsive to internal motivations (called “endogenous” motives) such as a sense of fair play, ethics, duty, and responsibility. Conversely, when people feel that outcomes are beyond their control, they tend to be more responsive to external motivations (called “exogenous” motives) such as punishment and deterrents. Managers must have organizational treatments for dealing with security behaviors based on the different underlying motivations and factors. It is not a one-size-fits-all proposition.

The collection of employee personal information and the practices of monitoring and surveillance are growing. There can be negative psychosocial outcomes if managers are not careful with these practices—they may backfire. To help ensure that the practices are effective and serve their intended purpose, managers must maintain the sense of managerial and organizational trust that the psychological contract depends on, and this can partly be accomplished by ensuring organizational justice.

We have now defined with a broad stroke security issues and policies and described how they fit into organizations—as well as some of the ways they specify security models and some of the roles of organizational members who are responsible for security policies. We discussed how security standards might be incorporated into commercial enterprises to improve their security, but that the rigor associated with these standards needs to be carefully weighed against other organizational considerations and priorities. We then discussed how that monitoring (surveillance) may act as an important prosecutorial tool in the case of contravention, but it can also have significant consequences for dedicated and law-abiding citizens.

We have now completed Section 1. We will turn our attention to some of the more technical aspects of security. Because the Internet has become a primary means for information interchange and electronic commerce, attacks against information resources threaten the economics in modern society; thus we will devote a fair amount of our textbook to this topic. Due to the interconnection of systems within and among organizations as a matter of globalization, such attacks can be carried out not only locally, but also anonymously and from great distances. We will next review some basics about technologies, and then move into how to implement security measures for them.

Topic Questions

6.1: Computer logs or emails are often not permissible in court as evidence unless they utilize what?

6.2: What is “ALE,” and what is it composed of?

6.3: The defensive coping behaviors toward chronic fear appeals to buffer or neutralize anxieties can be mitigated with what?

6.4: What is a psychological contract? And how does a psychological contract affect security-related behaviors?

6.5: Employees expectations of what the organization will provide and of what they (the employees) owe the organization is called:

___ Procedural justice

___ A psychological contract

___ An obligation

___ A best practice

6.6: Generating a message digest such that a sender cannot deny sending a message and a receiver cannot deny receiving it is called:

___ Non-repudiation

___ A security stance

___ The Biba model

___ Psychological contract

6.7: ISO 15408 is also known as:

___ The threat control model (TCM)

___ The orange book

___ Trusted Computing Base

___ Common Criteria

6.8: The physical or electronic observation of someones activities and behavior:

___ Is a privacy violation

___ Is a violation of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution

___ Is called surveillance

___ Is not permitted in an organization

6.9: A person who acts as a trusted intermediary between a complainant and the organization is called a(n):

___ Ombudsman

___ Corporate attorney

___ Broker

___ Moderator

6.10: Corporate monitoring of phone conversations is NEVER permitted in the United States because of wiretap laws.

___ True

___ False

Questions for Further Study

Q6.1: What are some ways that management in organizations use fear appeals to make their workforce vigilant against security threats?

Q6.2: Can you think of some ways that using fear appeals can backfire and lead to counterproductive behaviors?

Q6.3: What are some of the differences between monitoring centers, offsite storage facilities, replication centers, and disaster recovery centers? Discuss what each is used for and why the distinctions.

Q6.4: Give five examples or situations of a psychological contract.

Q6.5: How can managers protect themselves from complaints of unfairness in monitoring employees?

Clark and Wilson is a transaction oriented model defined by ACID properties.

Countermeasures are proactive implementations of what a policy might establish.

Information architecture is divided into macro- and micro-levels.

Organic organizational cooperation that enables company adaptation and agility is at odds with the concept of separation of duties.

Surveillance laws and regulations differ by country, state, and local levels.

References

1. Morrogh, E. (2003). Information architecture: An emerging 21st century profession. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

2. Carges, M., Belisle, D., & Workman, M. (1990). The portable operating system interface: Distributed database transaction processing systems and the XA protocol. IEEE Standard 1003.11 & X/Open-POSIX. Parsipanny NJ: ISO/IEC.

3. Straub, D. W., Carlson, P., & Jones, E. (1993). Deterring cheating by student programmers: A field experiment in computer security. Journal of Management Systems, 5, 33–48.

4. Solomon, M. G., & Chapple, M. (2005). Information security illuminated. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

5. Williams, B. R. (2009). Risk management follies. The ISSA Journal, 7, 6–7.

6. Sine, W. D., Mitsuhashi, H., & Kirsch, D. A. (2006). Revisiting Burns and Stalker: Formal structure and new venture performance in emerging economic sectors. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 121–132.

7. Tjaden, B. C. (2004). Fundamentals of security computer systems. Wilsonville, OR: Franklin, Beedle, & Associates.

8. Workman, M., & Gathegi, J. (2007). Punishment and ethics deterrents: A comparative study of insider security contravention. Journal of American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58, 318–342.

9. Workman, M. (2008). Mobility security and human behavior. In C. Bragdon (Ed.), Transportation security (pp. 71–95). Boston, MA: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

10. Bragdon, C. R. (2008). Transportation security. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

11. Hansen, K. L. (2002). Anxiety in the workplace post-September 11, 2001. The Public Manager, 31, 133–151.

12. Greenemeier, L. (2006, April). The fear industry. Information Week, pp. 35–49.

13. Workman, M. (2009). A field study of corporate employee monitoring: Attitudes, absenteeism, and the moderating influences of procedural justice perceptions. Information and Organization, 19, 218–232.

14. Fischer, R. J., & Green, G. (1992). Introduction to security. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

15. Grama, J. L. (2011). Legal issues in information security. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

16. Thomas, T. (2004). Network security. Indianapolis, IN: Cisco Press.

17. Harvey, C. (2007, April). The boss has new technology to spy on you. Datamation, pp. 1–5.

18. Fairweather, B. N. (1999). Surveillance in employment: The case of teleworking. Journal of Business Ethics, 22, 39–49.

19. D’Urso, S. C. (2006). Who’s watching us at work? Toward a structural-perceptual model of electronic monitoring and surveillance in organizations. Communication Theory, 16, 281–303.

20. Langenderfer, J., & Linnnhoff, S. (2005). The emergence of biometrics and its effect on consumers. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39, 314–338.

21. Holman, D., Chissick, C., & Totterdell, P. (2002). The effects of performance monitoring on emotional labor and well-being in call centers. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 57–81.

22. Lee, S., & Kleiner, B. H. (2003). Electronic surveillance in the workplace. Management Research News, 26, 72–81.

23. Workman, M., Bommer, W., & Straub, D. (2009). The amplification effects of procedural justice with a threat control model of information systems security. Journal of Behavior and Information Technology, 28, 563–575.