Cultural and Ethical Issues in Working with Culturally Diverse Patients and Their Families: The Use of the Culturagram to Promote Cultural Competent Practice in Health Care Settings

SUMMARY. In all aspects of health and mental health care–the emergency room, the outpatient clinic, inpatient facilities, rehab centers, nursing homes, and hospices–social workers interact with patients from many different cultures. This paper will introduce an assessment tool for health care professionals to advance understanding of culturally diverse patients and their families. [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2004 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Culturagram, cultural diversity, cultural competence, cultural and ethical issues, family assessment, culture and health care, ethical issues and health care

INTRODUCTION

The increasing cultural diversity of the United States has been the subject of news articles (Cohn, 2001; Purdum, 2000; Schmitt, 2001), as well as professional publications (Devore & Schlesinger, 1996; Gelfand & Yee, 1991; Homma-True, Greene, Lopez, & Temble, 1993; Lum, 2000; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). While immigrants in the early 1900s originated primarily from Western European countries, current immigrants come from Asia, South and Central America, and the Caribbean. It is projected that in this century over half of Americans will be from backgrounds other than Western Europe (Congress, 1994).

CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND CULTURAL COMPETENT PRACTICE

From the beginning the social work profession has provided services to culturally diverse clients. In the early days of the 20th century, social workers worked with immigrant populations in settlement houses. Since the late 1960s the NASW Code of Ethics has had an anti-discrimination section, and in last ten years there has been much stress on cultural competent practice. In the most recent Code of Ethics social workers are advised to understand cultural differences among clients and to engage in cultural competent practice (NASW, 1999), while the Council on Social Work Education (1996) mandates that each accredited school of social work include content on diversity. Cultural sensitivity often begins with self-assessment, and Ho (1991) has developed an ethnic sensitive inventory to help social workers measure their cultural sensitivity. The need for social workers in health care institutions to be attentive to the cultural diversity of patients has been stressed (Congress & Lyons, 1994).

Health care professionals have recently given much attention to the impact of cultural diversity on health care (Beckmann & Dysart, 2000; Chin, 2000; Cook & Cullen, 2000; Davidhizar, 1999; Dootson, 2000; Erlen, 1998). There has been some concern, however, that the curriculum of medical schools does not include content on cultural issues (Flores, 2000). A recent Diversity in Medicine project funded by the U.S. Dept of Education, however, developed a curriculum for medical students in training on cultural factors that affect diagnosis, treatment, and communication between patient and doctor (O’Connor, 1997). Although the need for health care professionals to be culturally sensitive has been repeatedly stressed, providing health care to diverse cultural groups has been seen as one of the most challenging for health care providers (Davidhizar, Bechtel, & Giger, 1998).

While developing cultural competent practice is an ongoing goal for social workers (Lum, 2000), the diversity of clients’ backgrounds, especially in urban areas, makes this process most challenging. The presence of families from 125 nations in one zip code in Queens (National Geographic, 1998) attests to the challenges that face health care social workers. How can a social worker know and understand the culture of each patient? Some literature has focused on teaching social workers specific characteristics of different ethnic populations (McGoldrick, 1998; Ho, 1987; Goldenberg, 2000).

Considering a family only in terms of a generic cultural identity, however, may lead to over generalization and stereotyping (Congress, 1994, 1997). In working with culturally diverse patients, social workers soon learn that one patient and family is very different from another. For example, an undocumented Mexican family that recently immigrated to the United States may access and use health care very differently than a Puerto Rican family that has lived in the United States for thirty years. Yet both families are Hispanic.

Even two patients from the same ethnic background may be dissimilar. For example one Puerto Rican patient who is hospitalized for a heart condition may be very different from another Puerto Rican patient with a similar medical condition. Generalizations about people from similar ethnic backgrounds may be not always give the most accurate understanding. When attempting to understand culturally diverse patients and families, it is important to assess the family from a multi dimensional cultural perspective.

CULTURAGRAM

The culturagram grew out of the author’s experience in working with families from different cultural backgrounds. Two social work assessment tools, the ecomap (Hartman & Laird, 1983) that looked at families in relationship to the external environment, and the genogram (McGoldrick & Gerson, 1985) that examines internal family relationships, are useful tools in assessing families, but do not emphasize the important role of culture in understanding families.

The culturagram (Congress, 1994; Congress, 1997) a family assessment instrument discussed in this journal article was originally developed to help social workers understand culturally diverse clients and their families. During the last seven years the culturagram has been applied to work with people of color (Lum, 2000), battered women (Brownell & Congress, 1998), children (Webb, 1996, 2001), and older people (Brownell, 1998). This article applies the culturagram to work with patients and their families in health and mental health settings.

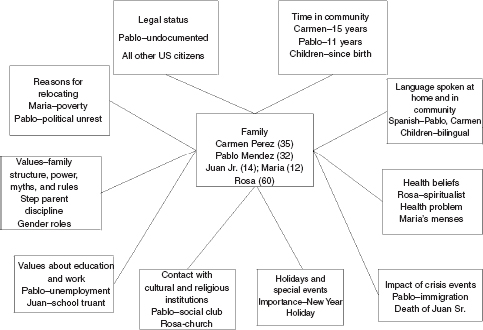

Developed in 1994 and revised in 2000, the culturagram (see Figure 1) examines the following 10 areas:

• Reasons for relocation

• Legal status

• Time in community

• Language spoken at home and in the community

• Health beliefs

• Crisis events

• Holidays and special events

• Contact with cultural and religious institutions

• Values about education and work

• Values about family–structure, power, myths, and rules

Reasons for Relocation. Reasons for relocating vary among families. Many families come because of economic opportunities in America, whereas others relocate because of political and religious discrimination in their country of origin. For some it is possible to return home again, and they often travel back and forth for holidays and special occasions. Others know that they can never go home again. Some families move within the United States, often from a rural to a more urban area. Some immigrants come from backgrounds with very limited formal health care and may have associated health problems.

After relocating from their native countries, immigrant families often experience differing amounts of stress that is manifested in anxiety and depressive symptoms. There may be feelings of profound loss if they have left a land to which they can never return. Health care professionals need to understand the reasons for relocation, as this information may be helpful in understanding the physical and psychological symptoms of patients and their families.

FIGURE 1. Culturagram–2000

Legal Status. The legal status of a family may have an effect on patients and their families. If a family is undocumented and fears deportation, members may become secretive and socially isolated. Patients may have difficulty accessing treatment because of their undocumented status. They may also avoid seeking treatment until their health condition is very severe, less they will have to disclose their undocumented status. An important first step for the health care professional is to establish trust and to reassure the undocumented patient and family about the confidentiality of contact with health care professionals. This may not be easy especially in the patient has come from a country in which confidentiality is unknown (Congress, 1994).

Length of Time in the Community. The length of time in the community may differ for patients and their families. Often family members who have arrived earlier are more acculturated than other members. Another key factor is that family members are different ages at the time they relocate. Because of attending American schools and developing peer relationships, children are often more quickly assimilated than their parents. Children often become interpreters for parents in contacts with schools, health care providers and social service agencies.

Language. Language is the mechanism by which families communicate with each other. Often families may use their own native language at home, but may begin to use English in contacts with the outside community. Sometimes children may prefer English, as they see knowledge of this language as most helpful for survival in their newly adopted country. This may lead to conflict in families. A most literal communication problem may develop when parents speak no English, and children speak only minimally their native tongue.

Often children are used as interpreters in health care settings. Exposure of the child to sensitive health care issues and role reversals may be the unwanted results. Another concern is how can the health care provider insure that the patient has given informed consent, if it is unclear that information has been accurately understood. This points to the need for bilingual staff to facilitate the care of culturally diverse patients.

Health Beliefs. This part of the culturagram must be thoroughly explored by social workers working in health care settings. Families from different cultures have varying beliefs about health, disease, and treatment (Congress & Lyons, 1992). There are significant differences in how culturally diverse populations seek health care (Zambrana, Dorrington, Wachsman, & Hodge, 1994), view chronic illness (Anderson, Blue, & Lau, 1991; Wallace, Levy-Storms, Kinston, & Andersen, 1998), and death and dying (Parry & Ryan, 1995). Differing life expectancies have also been identified (Devore & Schlesinger, 1998).

Often health issues impact adversely on culturally diverse families, as for example when the primary wage earner with a serious illness is no longer able to work, a family member has HIV/AIDS, or a child has a chronic health condition such as asthma or diabetes. Also, mental health problems can impact negatively on families. Coping with the aftermath of losses associated with immigration, a mother may be too depressed to care for her children or a child may be acting out in school as a result of feeling an outsider in a new country. Families from different cultures especially if they are undocumented may encounter barriers in accessing medical treatment, or may prefer alternative resources for diagnosing and treating physical and mental health conditions (Devore & Schlesinger, 1996).

Many immigrants may use health care methods other than traditional Western European medical care involving diagnosis, pharmacology, x-rays, and surgery (Congress & Lyons, 1992). Some immigrants may choose to use a combination of western medicine and traditional folk beliefs.

An important issue is that of preventive care. We continually hear from early childhood about the importance of regular checkups. Managed care has reinforced the concept of regular preventive care in order to avoid future expensive medical treatment. Many new arrivals may not share American health care values about the importance of preventive care, as the following example indicates.

A mother brought her 18-month-old son to the emergency room with a very high fever. The doctor questioned if the child had been seen previously in the Well Baby Clinic. The mother responded that she had never brought the child for care previously, as he had not been sick.

When a member of a cultural diverse family is hospitalized, there may be issues in adjusting to hospital policies and procedures. For example, a family may wish to have all family members including small children come to the patient’s hospital room. There may be concerns about limited visiting hours or the number of concurrent visitors. Families may want to bring the patients foods that are contrary to medically prescribed diets. The health care professional has a responsibility to explore the health beliefs of the patient and family. An important ethical dilemma arises when the health beliefs of the patient may seem contrary to those of the employing health care institution.

Crisis Events. Families can encounter developmental crises as well as “bolts from the blue” crises (Congress, 1996). Developmental crises may occur when a family moves from one life cycle stage to another. A particular stressful time for culturally diverse families may be when children become adolescents. Parents with expectations for adolescents to work or care for younger siblings may not accept that American adolescents often want to socialize with peers. Different familial attitudes about sexuality are often quite apparent for health care professionals who work in adolescent health clinics.

Families also deal with “bolts from the blue” crises in different ways. A family’s reactions to crisis events are often related to their cultural values. For example, a father’s accident and subsequent inability to work may be especially traumatic for an immigrant family in which the father’s providing for the family is an important family value. While rape is certainly traumatic for any family, the rape of a teenage girl may be especially traumatic for a family who values virginity before marriage. Also, the serious illness and death of an elderly member may have tremendous impact on the culturally diverse family who look to the elderly family member for major support and decision-making.

Holidays and Special Events. Each family has particular holidays and special events. Some events mark transitions from one developmental stage to another; for example, a christening, a bar mitzah, a wedding, or a funeral. It is important for the social worker to learn the cultural significance of important holidays for the patient and family, as they are indicative of what families see as major transition points within their family. It may be particularly traumatic for culturally diverse patients who are too ill to participate in an important family celebration.

Contact with Cultural and Religious Institutions. Contact with cultural institutions is often very important for immigrant patients and their families. Family members may use cultural institutions differently. For example, a father may belong to a social club, the mother may attend a church where her native language is spoken, and adolescent children may refuse to participate in either because they wish to become more Americanized.

Religion may provide much support to patients and their families and the health care provider will want to explore the patient’s contact with formal religious institutions, as well as informal spiritual beliefs. Knowledge of a patient and his/her family’s religious beliefs are particularly important for health care professionals whose patients are struggling with serious illnesses.

Values About Education and Work. All families have differing values about work and education, and culture is an important influence on such values. Social workers in health care settings must explore what these values are in order to understand their patients and families. Economic and social differences between the country of origin and America can affect immigrant families. For example, employment in a low status position may be very denigrating to the male breadwinner. It may be especially traumatic for the immigrant family when the father can not find any work or only works on an irregular basis. Another very stressful event for immigrant families is when the breadwinner is not able to work because of serious illness, accident, or disability. For workers who are marginally employed there may not be worker’s compensation or social security benefits to help the patient and families when the primary breadwinner is not able to work.

Immigrant families usually believe in the importance of education for their children. Yet children may be expected to work to maintain families in times of economic hardships. With a strong commitment to family, culturally diverse families with a parental member who is struggling with a serious illness may not want children to leave home to pursue further education.

Values About Family–Structure, Power, Myths, and Rules

Each family has its unique structure, beliefs about power relationships, myths, and rules. Some of these may be very unique to the cultural background of the family. The clinician needs to explore these family characteristics individually, but also understand in the context of the family’s cultural background. Culturally diverse families may have differing beliefs about male-female relationships especially within marriage. Families from cultural backgrounds with a male dominant hierarchical family structure may encounter conflict in American society with a more egalitarian gender relationships. This may result in an increase in domestic violence among culturally diverse families. The health care professional needs to be sensitive to recognizing family violence within culturally diverse families.

If there are more rigidly proscribed household roles for women, there may much stress on the family when the woman/wife/mother is hospitalized and/or unable to carry out usually household responsibilities. Other female relatives who previously would have helped out during a health crisis may have remained behind in the country of origin and thus not be available to the immigrant family.

Finally, child-rearing practices especially in regard to discipline may differ in culturally diverse families. The social work in health care settings is always very alert to signs of child abuse or neglect, as social workers are mandated reporters of child abuse. Since health care professionals want to be culturally sensitive, however, they may face a dilemma about whether to report a mother who is disciplining a child using mild physical punishment that is acceptable in her country of origin.

The following case vignette will be used to illustrate how the culturagram can be used to understand better a family with its unique cultural background:

Thirty-five-year-old Mrs. Carmen Perez was seen in an outpatient mental health agency in her community because she was having increasing conflicts with her 14-year-old son Juan who had begun to cut school and stay out late at night. She also reported that she had a 12-year-old daughter Maria who was “an angel.” Maria was very quiet, never wanted to go out with friends, and instead preferred to stay at home helping her with household chores. Maria was often kept out of school to accompany and interpret for her mother at medical appointments. Mrs. Perez did express concern that Maria had recently begun to menstruate. Every month she became ill with severe cramps and vomiting. Mrs. Perez commented that this was women’s cross that that there was nothing to be done about this.

Mrs. Perez indicated the source of much conflict was that Juan believed he did not have to respect Pablo, as he was not his real father. Juan complained that his mother and stepfather were “dumb” because they did not speak English. The past Christmas holidays had been especially difficult, as Juan had disappeared for the whole New Years weekend.

At 20 Mrs. Perez had moved to the United States from Puerto Rico with her first husband Juan Sr., as they were very poor in Puerto Rico and had heard there were better job opportunities here. Juan Sr. had died in an automobile accident on a visit back to Puerto Rico when Juan Jr. was 2. Shortly afterwards she met Pablo who had come to New York from Mexico to visit a terminally ill relative. After she became pregnant with Maria, they began to live together. Pablo indicated that he was very fearful of returning to Mexico as several people in his village had been killed in political conflicts.

Because Pablo was undocumented, he had only been able to find occasional day work. He was embarrassed that Carmen had been forced to apply for food stamps. Pablo was beginning to spend more time drinking and hanging out on the corner with friends.

Carmen was paid only minimum wage as a health care worker. She was very close to her mother who lived with the family. Her mother had taken her to a spiritualist to help her with her family problems, before she had come to the neighborhood agency to ask for help. Pablo has no relatives in New York, but he has several friends at the social club in his neighborhood.

After completing the culturagram (see Figure 2), the social worker was better able to understand the Perez family, assess their needs and begin to plan for treatment. For example, she noted that Juan’s undocumented status was a source of continual stress in this family. She referred Juan to a free legal service that provided help for undocumented people in securing legal status. The social worker also recognized that there had been much conflict within the family because of Juan’s behavior. She has also concerned that Maria might have unrecognized medical problems and referred her for a health consultation. She also helped Maria and her mother talk to an adolescent health educator who was bilingual and bicultural. Finally she was keenly aware of family conflicts between Pablo and his stepson Juan. To help the family work out their conflicts the social worker referred the family to a family therapist who was culturally sensitive and had had experience in working out intergenerational conflicts.

The culturagram has been seen as an essential tool in helping social workers work more effectively with families from many different cultures. Initial evaluation of the culturagram has been positive, and there are plans to assess the effectiveness of the culturagram in promoting culturally competent practice.

FIGURE 2. Culturagram–2000

Implications

Developing culturally sensitive practice, however, is only the first step. In addition, the health care social worker has an important responsibility to educate other health care providers about the beliefs of culturally diverse patients and their families. Fandetti and Goldner (1988) stress the important role of the social worker as cultural mediator. In a previous article Congress and Lyons (1994) outlined the following guidelines for social workers in health care settings:

1. increase sensitivity to culturally diverse beliefs;

2. learn more about clients’ beliefs about health, disease, and treatment;

3. avoid stereotyping and emphasize individual differences in diagnostic assessments;

4. increase the ability of culturally diverse clients to make choices;

5. enlarge other health care professionals’ understanding of cultural differences in the health beliefs of clients; and

6. advocate for understanding and acceptance of differing health beliefs in the health care facility and in the larger community. (pp. 90-92)

A crucial role for the social worker in a health care setting is that of advocate on a micro and macro level for the culturally diverse patients and families (Congress, 1994).

Culturally sensitive health care social workers, however, may face an ethical dilemma between advocating for a patient’s right to choose alternative health care and the health care practices and policies of employing institutions. Goldberg (2000) describes a challenge for social workers between respecting the beliefs of all cultures versus supporting basic human rights. This conflict has important implications for social workers in health care settings. While social workers are respectful of different beliefs about health treatment, what if the cultural practice is potentially life threatening? For example, how does the health care provider work with a culturally diverse family who chooses visits to a faith healer and special herbs, rather than chemotherapy and radiation for a child diagnosed with leukemia?

In addition to responsibility to clients/patients, social workers also have an ethical duty to follow the policies of their employing agency (NASW, 1999). What if the behaviors of a culturally diverse patient are contrary to hospital policies and procedures? How does the social worker work with a hospitalized culturally diverse patient who wants her two-year-old child to visit, whose mother brings in special food contrary to the hospital diet? When and where should the health care social worker clearly set limits with the patient or advocate for a change in hospital policy? These questions continue to be challenges for social workers in health care settings.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J., Blue, C., and Lau, A. (1991). Women’s perspectives on chronic illlness: Ethnicity, ideology and restructuring of life. Social Science and Medicine 33(2) 101-113.

Beckmann, C. and Dysart, D. (2000). The challenge of multicultural medical care. Contemporary OB GYN 45(120) 12-25.

Brownell, P. (1997). The application of the culturagram in cross cultural practice with elder abuse victims. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 9(2), 19-33.

Brownell, P. and Congress, E. (1998). Application of the culturagram to assess and empower culturally and ethnically diverse battered women. In A. Roberts (ed). Battered women and their families: Intervention and treatment strategies (pp. 387-404). New York: Springer, Press.

Chin, J.L. (2000). Culturally competent health care Health Forum 115(1), 25-37.

Colon, D. (2001, March 16). Immigration Fueling Big U.S. Cities Washington Post, Section A, p. 1.

Congress, E. (1994). The use of culturagrams to assess and empower culturally diverse families. Families in Society, 75, 531-540.

Congress, E. (1996). Family crisis–life cycle and bolts from the blue: Assessment and treatment. In A. Roberts (ed.), Crisis intervention and brief treatment: Theory, techniques, and applications (pp. 142-159). Chicago: Nelson Hall.

Congress, E. (1997). Using the culturagram to assess and empower culturally diverse families. In E. Congress, Multicultural perspectives in working with families (pp. 3-16). New York: Springer Press.

Congress, E. and Lyons, B. (1992). Ethnic differences in health beliefs: Implications for social workers in health care settings. Social Work in Health Care, 17 (3), 81-96.

Congress, E. and Lynn, M. (1994). Group work programs in public schools: Ethical dilemmas and cultural diversity. Social Work in Education, 16(2), 107-114.

Cook, P. and Cullen, J. (2000). Diversity as a Value in Undergraduate Nursing Education. Nursing and Health Care Perspectives 21(4) 178-191.

Davidhizar, R., Bechtel, G., and Giger, J.N. (1998). A model to enhance culturally competent Care. Hospital Topics 76(2) 22-26.

Davidhizar, R., Havens, R., and Bechtel, G. (1999). Assessing culturally diverse pediatric clients. Pediatric Nursing 25(4) 371-386.

Devore, W. and Schlesinger, E. (1999). Ethnic-sensitive social work practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Dootson, G. Adolescent Homosexuality and Culturally Competent Nursing. Nursing Forum 35(3) 13-25;

Erlen, J. (1998). Culture, ethics, and respect: The bottom line is understanding. Orthopaedic Nursing 17(6), 79-85.

Flores, G. (2000). The teaching of cultural issues in US and Canadian medical schools Journal of the American Medical Society 284(3), p. 284-290..

Gelfand, D. and Yee, B. (1991). Trends and forces: Influence of immigration, migration, and acculturation of the fabric of aging in America. Generations 15, 7-10.

Goldberg, M. (2000). Conflicting Principles in Multicultural Social Work. Families in Society 81(1), 12-33.

Hartman, A. and Laird, J. (1983). Family oriented treatment. New York: The Free Press.

Ho, M.K. (1987). Family therapy with ethnic minorities. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Homma-True, R., Greene, B., Lopez, and Temble, J. (1993). Ethnocultural diversity in clinical psychology. Clinical Psychologist 46, 50-63.

Lum, D. (2000). Social work practice and people of color: A process-stage approach (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks Cole.

McGoldrick, M. and Gerson, R. (1985). Genograms in family assessment. New York: W.W. Norton.

National Association of Social Workers. (1999). Code of ethics. Washington DC: NASW Press.

National Geographic (September, 1998). All the world comes to Queens.

O’Connor, B. (1997). Applying folklore in medical education. Southern Folklore 54(2) 67-78.

Parry, J. and Ryan A. (1995). A cross-cultural look at death, dying, and religion. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth.

Purdum, T. (2000, July 4). Shift in the mix alters face of California. The New York Times. Section A, p. 1

Schmidt, E. (2000, April 3). US has biggest 10-year population rise ever. The New York Times. Section A, p. 10.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Redistricting Public Law 94-171, summary file, Tables PL 1 and PL2.

Wallace, S., Levy-Storms, L., Kinston, R., and Andersen, R. (1998). The persistence of race and ethnicity in the use of long term care. Journal of Gerontology 53(2), 104-113.

Webb, N.B. (1996). Social work practice with children. New York: Guilford Press

Webb, N.B. (2001). Helping culturally diverse children and their families. New York: Columbia University Press.

Zambrana, R., Ell, K., Dorrington, C., Wachsman, L, and Hodge, D. (1994). The relationship between psychosocial status of immigrant Latino mothers and use of emergency pediatric services Health and Social Work 19, 93-102.

Elaine P. Congress is Associate Dean at Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service, 113 West 60th Street, New York, NY 10023 USA (E-mail: [email protected]).

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the International Health and Mental Health Conference in Tampere, Finland in July 2001.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Cultural and Ethical Issues in Working with Culturally Diverse Patients and Their Families: The Use of the Culturagram to Promote Cultural Competent Practice in Health Care Settings.” Congress, Elaine P. Co-published simultaneously in Social Work in Health Care (The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 39, No. 3/4, 2004, pp. 249-262; and: Social Work Visions from Around the Globe: Citizens, Methods, and Approaches (ed: Anna Metteri et al.) The Haworth Social Work Practice Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 2004, pp. 249-262. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: [email protected]].