CHAPTER 2

Bodies of Knowledge and Competency Standards in Project Management

ALAN M. STRETTON, UNIVERSITY OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY, ARLINGTON, VA

The original version of this chapter, published in the first edition of this handbook, was written when the only knowledge standard for project management was the 1987 Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®)1 developed by the Project Management Institute (PMI), headquartered in the United States. After publication of the first edition, the PMBOK® was completely rewritten and renamed A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) in 1996, with revised editions published in 2000, 2004, and 2008, but with the basic 1996 structure unchanged.2

In the meantime, other bodies of knowledge of project management have been developed around the world, notably in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Japan. These are all markedly different from the PMBOK® Guide, but are the de facto project management knowledge standards in their respective geographic domains. Thus, no single universally accepted body of knowledge of project management is currently recognized.

This situation has stimulated numerous efforts to try and define which topics should be included in a global body of knowledge of project management, and how they might be structured. The most notable of these was the OLCI, initiated in 1998. Results from this initiative will be discussed below.

Another development is the adoption in some countries of performance-based competency standards, rather than knowledge standards, as a basis for assessing and credentialing project managers. Another global effort, this time for the development of a framework of Global Performance Based Standards for Project Management Personnel, was initiated in 2000. Progress and prospects are discussed below. First, we will examine the origins and natures of key bodies of knowledge and competency standards for project management.

WHY A BODY OF KNOWLEDGE FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT?

Knowledge standards or guides, which typically take the form of bodies of knowledge, focus primarily on what project management practitioners need to know to perform effectively.

The most compelling argument for having a body of knowledge for project management is to help overcome the “reinventing-the-wheel” problem. A good body of knowledge should help practitioners do their jobs better, by both direct referencing and by use in more formal educational processes.

Koontz and O’Donnell express the need as follows: “In managing, as in any other field, unless practitioners are to learn by trial and error (and it has been said that managers’ errors are their subordinates’ trials), there is no other place they can turn for meaningful guidance than the accumulated knowledge underlying their practice. …”3

Beginning in 1981, the Project Management Institute (PMI) took formal steps to accumulate and codify relevant knowledge by initiating the development of what became their Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®). The perceived need to do so arose from the PMI’s long-term commitment to the professionalization of project management. As they stated at the time, “… there are five attributes of a professional body:

1. An identifiable and independent project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® standards).

2. Supporting educational programs by an accredited institution (Accreditation).

3. A qualifying process (Certification).

4. A code of conduct (Ethics).

5. An institute representing members with a desire to serve….”4

The initial overambitious goal of trying to codify an entire body of knowledge—surely a dynamic and changeable thing—was tempered in 1996 by the change in title to A Guide to… and the statement that the PMBOK® Guide was in fact, “a subset of the … Body of Knowledge that is generally accepted as good practice.” That is to say that the PMBOK® Guide is designed to define a recommended subset rather than describe the entire field.

In summary, PMI sees its subset of the body of knowledge, as set forth in the PMBOK® Guide, as a basis for the professionalization of project management. The PMBOK® Guide is used to support education programs and to accredit programs for degree-granting educational institutions. A test on knowledge of the PMBOK® Guide is part of the qualifying process for its Project Management Professional (PMP) certification. The United Kingdom, European, and Japanese bodies of knowledge were developed for somewhat different purposes, but they all share the purpose of providing a basis for assessment and certification of project management practitioners.

We now look at some of the principal bodies of knowledge of project management in more detail.

PMI’s PMBOK® Guide

PMI has produced the oldest and most widely used body of knowledge of project management, which was been modified substantially over the years. In the words of an editor of the Project Management Journal: “It was never intended that the body of knowledge could remain static. Indeed, if we have a dynamic and growing profession, then we must also have a dynamic and growing body of knowledge.”5

The precursor of the PMBOK® was PMI’s ESA (Ethics, Standards, and Accreditation) report of 1983,5 which nominated six primary components, namely the management of scope, cost, time, quality, human resources, and communications.

The 1987 PMBOK® was an entirely new document, and the first separately published body of knowledge of project management. It added contract/procurement management and risk management to the previous six primary components.

The 1996 PMBOK® Guide was a completely rewritten document, which added project integration management to the existing eight primary components. The nine components were then renamed Project Management Knowledge Areas, with a separate chapter for each. Each knowledge area has a number of component processes, each of which is further discussed in terms of inputs, tools and techniques, and outputs.

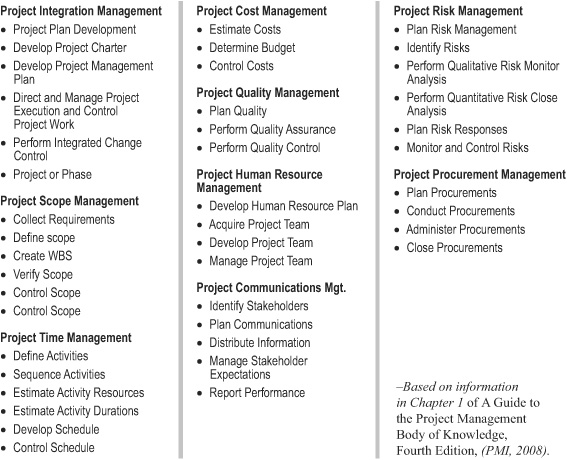

The knowledge areas and their component processes in the 2008 PMBOK® Guide, Fourth Edition, are listed in Table 2-1. As you can see, there are forty-two component processes identified in this model.

TABLE 2-1. THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESSES, LISTED BY KNOWLEDGE AREA

Discussions of the nine knowledge areas and component processes are preceded by two chapters on the Project Management Framework, one is an introductory chapter and one is about the project life cycle and organization. These are followed by a section on the standard for project management, which includes a chapter on project management processes for a project.

Whereas the PMBOK® Guide (1996) aimed to identify and describe generally accepted knowledge and practices—that is, those that are applicable to most projects most of the time and about which there is widespread consensus about their value and usefulness—a major conceptual change for the third and fourth editions is that they have replaced the criterion “generally accepted” from the previous editions “to identify that subset of the Project Management Body of Knowledge that is generally recognized as good practice” [author’s italics], and they go on to explain that “ ‘good practice’ means that there is general agreement that the correct application of these skills, tools, and techniques can enhance the chances of success over a wide range of different projects. Good practice does not mean that the knowledge described should always be applied uniformly on all projects; the project management team is responsible for determining what is appropriate for any given project.”7

While acknowledging that “much of the knowledge needed to manage projects is unique or nearly unique to project management,” the 2000 PMBOK® Guide went on to note that it does overlap other management disciplines, and that general management skills provide much of the foundation for building project management skills:

On any given project, skill in any number of general management areas may be required…. These skills are well documented in the general management literature and their application is fundamentally the same on a project…. There are also general management skills that are relevant only on certain projects or in certain application areas. For example, team member safety is critical on virtually all construction projects and of little concern on most software development projects.8

In the PMBOK® Guide, Third Edition, this paragraph was replaced by a table defining “general management” as the “planning, organizing, staffing, executing, and controlling the operations of an ongoing enterprise” and listing the categories of such skills that might be of use to the project manager, including financial management and accounting; sales and marketing; contracts and commercial law; manufacturing and distribution; logistics and supply chain management; strategic planning, tactical planning, and operational planning; organizational behavior and development; personnel administration and associated topics; and information technology; among others.

In the fourth edition, specific discussion of general management knowledge and skills has evidently been dropped, but a new appendix on project management people skills has been added, covering such skills as leadership, team building, motivation, communication, influencing, decision making, political and cultural awareness, and negotiation.

In summary, the PMBOK® Guide has focused on (project) management skills that are generally recognized as good practice and has not included in the knowledge areas those general management skills that may be required only on some projects and/or only on some occasions.

The Association of Project Management Body of Knowledge (APMBOK®)

Morris9 [11] notes that when the United Kingdom’s APM launched its certification program in the early 1990s, it was because the APM felt that PMI’s PMBOK® did not adequately reflect the knowledge base that project management professionals need. It therefore developed its own body of knowledge, which differs markedly from PMI’s.10

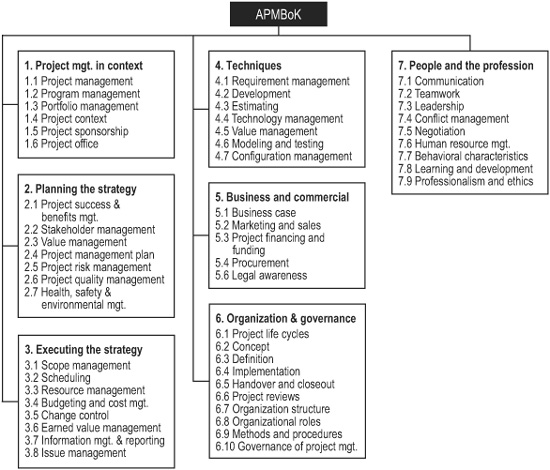

The fifth edition (2006) of APMBOK® was organized into seven main sections, with a total of 52 component items, as represented in Figure 2-1. There are brief discussions of all headings and topics, and references given for each topic.

Morris discusses the reasons why APM did not use the PMBOK® model. In essence, he says that the different models reflect different views of the project management discipline. He notes that while the PMI model is focused on the generic processes required to accomplish a project “on time, in budget, and to scope, “APM’s reflects a wider view of the discipline, “addressing both the context of project and the technological, commercial, and general management issues, which it believes are important to successfully accomplishing projects.”

FIGURE 2-1. THE ASSOCIATION OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT BODY OF KNOWLEDGE

… all the research evidence … shows that in order to deliver successful projects, managing scope, time, cost, resources, quality, risk, procurement, and so forth … alone are not enough. Just as important—sometimes more important—are issues of technology and design management, environment and external issues, people matters, business and commercial issues, and so on. Further, the research shows that defining the project is absolutely central to achieving project success. The job of managing the project begins early in the project, at the time the project definition is beginning to be explored and developed, not just after the scope, schedule, budget, and other factors have been defined … APM looked for a structure that gave more recognition to these matters.11

One of the key differences between the PMI and APM approaches is that the PMBOK® Guide’s Knowledge Areas have focused on project management skills that are generally recognized as good practice, while contextual issues and the like are discussed separately in its Framework section. On the other hand, the APMBOK® includes knowledge and practices that may apply to some projects and/or part of the time, which is a much more inclusive approach. This is exampled by the fact that the PMBOK® Guide specifically excludes safety, while the APMBOK® specifically includes safety.

European Bodies of Knowledge

Following the publication and translation of the first editions of the APMBOK® in 1992 and 1994, several European countries, including Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, and The Netherlands, developed their own bodies of knowledge.

The International Project Management Association (IPMA), a federation of national project management associations, mainly European, developed an IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB) in the late 1990s. This was reviewed and updated in 1999 (Version 2) and again in 2006 (Version 3).12 The primary purpose of the ICB is to provide a reference basis for its member associations to develop their own National Competence Baselines (NCBs). Another purpose of the ICB was to “harmonize” the then-existing European bodies of knowledge, particularly those of the UK, France, Germany, and Switzerland. The majority of members have since developed their own baselines, which may include additional elements to reflect any cultural differences and provide a basis for certification of their project managers.

In spite of its name, the majority of the content of the ICB can be seen primarily as a knowledge guide although it is explicitly intended as a basis for assessment and certification at four levels IPMA A, B, C, and D. Competence in the ICB is defined as a “collection of knowledge, personal attitudes, skills and relevant experience needed to be successful in a certain function.”

The ICB comprises some 46 competence elements of which 20 are classified as technical, 15 as behavioral, and 11 as contextual. The 46 competence elements are required to be included in each member’s NCB.

Japan’s P2M

In mid-1999, Japan’s Engineering Advancement Association (ENAA) received a commission from the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry to establish a new Japanese-type project management knowledge system and a qualification system. ENAA established a committee for the introduction, development, and research on project management, which produced A Guidebook of Project & Program Management for Enterprise Innovation—officially abbreviated to P2M—in 2001, with English revisions in 2002, 2004 and 2008.13

The task of issuing, maintaining, and upgrading P2M was undertaken by the Project Management Professionals Certification Center (PMCC) of Japan (formed in 2002), which also implemented a certification system for project professionals in Japan, based on P2M. The PMCC consolidated its organization with that of the Japan Project Management Forum (JPMF, which was originally inaugurated in 1998) in November 2005, to make a fresh start as the Project Management Association of Japan (PMAJ), which is the publisher of the 2008 edition of P2M.

The rationale for developing P2M and the certification system was a perceived need for Japanese enterprises to develop more innovative approaches to developing their businesses, particularly in the context of the increasingly competitive global business environment and also a perceived need to provide improved public services. The key concept in addressing this need is “value creation.” The recommended means of achieving “value creation” is through developing an enterprise mission, then strategies to accomplish this mission, followed by planned programs to implement these strategies, and then specific projects to achieve each of the programs. The focus of P2M is on how to facilitate the effective planning, management, and implementation of such programs and projects.

The original Japanese document comprises approximately 420 pages, so it is a large and very detailed document. Alone among the main project management bodies of knowledge, P2M not only covers the management of single projects, but also has a major section specifically on program management.

On the project management side, P2M has chapters on the following project management topics, under the overall heading of Individual Management.

1. Project Strategy Management

2. Project Finance Management

3. Project Systems Management

4. Project Organization Management

5. Project Objectives Management

6. Project Resources Management

7. Risk Management

8. Program and Project Information Management

9. Project Relationships Management

10. Project Value Management

11. Project Communications Management.

TOWARD A GLOBAL BODY OF KNOWLEDGE?

In the current situation, no one globally accepted body of knowledge of project management exists. Each main professional association has a vested interest in maintaining its own body of knowledge, as each case has involved such a big investment in, and commitment to, subsequent certification processes. It is, therefore, difficult to envisage any situation that might prompt professional associations to voluntarily cooperate to develop a global body of knowledge to which they would commit themselves.

Nonetheless, there have been many Global Forums since the mid-1990s, often in association with major project management conferences, which indicate a wide recognition that a globally recognized body of knowledge would be highly desirable.

One particular initiative was the coming together of a small group of internationally recognized experts to initiate workshops, beginning in 1998, to work toward a global body of project management knowledge. This group, known as OLCI (Operational Level Coordination Initiative) has recognized that one single document cannot realistically capture the entire body of project management knowledge, particularly emerging practices, such as in managing “soft” projects (e.g., some organizational change projects), cutting edge research work, unpublished materials, and implicit as well as explicit knowledge and practice. Rather, there has emerged a shared recognition that the various guides and standards represent different and enriching views of selected aspects of the same overall body of knowledge.14

COMPETENCY STANDARDS

Competency has been defined as “the ability to perform the activities within an occupation or function to the standard expected in employment.”15 There are two primary approaches to inferring competency: attribute based and performance based.

The attribute-based approach involves definition of a series of personal attributes (e.g., a set of skills, knowledge, and attitudes) that are believed to underlie competence and then testing whether those attributes are present at an appropriate level in the individual. The attribute-based approach appears to be the basis for PMI’s Project Manager Competency Development Framework (PMCDF),16 although this is intended for use in professional development for project managers rather than in selection or performance evaluation.

The performance-based approach is to observe the performance of individuals in the actual workplace, from which underlying competence can be inferred. This has been the approach adopted by the Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM) as a basis for its certification/registration program.

Australian National Competency Standards for Project Management (ANCSPM)

Several factors combined to lead AIPM to develop competency standards, including a recognition that the possession of knowledge about a subject does not necessarily mean competence in applying that knowledge in practice. The Australian Government was also very influential, through its Department of Employment, Education, and Training, which very actively promoted the development of national competency standards for the professions.

The format of Australian Competency Standards emphasizes performance-oriented recognition of competence in the workplace, and includes the following main components:

![]() Units of competency: the significant major functions of the profession.

Units of competency: the significant major functions of the profession.

![]() Elements of competency: the building blocks of each unit of competency.

Elements of competency: the building blocks of each unit of competency.

![]() Performance criteria: the type of performance in the workplace that would constitute adequate evidence of personal competence.

Performance criteria: the type of performance in the workplace that would constitute adequate evidence of personal competence.

![]() Range indicators: describe more precisely the circumstances in which the performance criteria would be applied.

Range indicators: describe more precisely the circumstances in which the performance criteria would be applied.

The ANCSPM units of competency align with the nine knowledge areas of the PMBOK® Guide. The elements of competency are expressed in action words, such as determine, guide, conduct, implement, assess outcomes, and the like. There are generally three elements of competency for each unit, but occasionally more. There are typically two to four performance criteria for each element of competency. ANCSPM also has substantial supporting material, which includes “a broad knowledge and understanding of … [various relevant topics]” and checklists of “substantiating evidence.”17

Other Competency Standards

South Africa is developing its own performance-based competency standards. Standards have been completed for a National Certificate in Project Management—NQF Level 4 (SAQA), and work on Levels 3 and 5 is proceeding.18

In the UK, the Association for Project Management published the APM Competence Framework in 2008.19 This is linked to the APM Body of Knowledge (5th Edition) and the ICB-IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0. Earlier, the Occupational Standards Council for Engineering produced standards for Project Controls (1996) and for Project Management (1997). These were reviewed in 2001, and the revised standards endorsed by the regulatory authorities in 2002. These are now the responsibility of the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board.20

The above standards are formally recognized and provide the basis for award of qualifications within their respective national qualifications frameworks.

Toward Global Performance-Based Competency Standards?

As noted, a global effort for the development of a framework of Global Performance-Based Standards for Project Management Personnel (now known as the Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards—GAPPS) was initiated in 2000. The work of an international group, with representatives from major international project management associations, has been facilitated from the outset by Dr. L.H. Crawford of ESC Lille, France, and Bond University, Australia. The philosophy of this endeavor is to be maximally inclusive, so that emerging standards will incorporate input from virtually all project management knowledge and competency standards developed to date.

These standards have the potential to be adopted as truly global, because each project management institute/association should be able to see a direct correspondence between its standards and the Global Performance Based Standards. A table for evaluating the management complexity of project roles has been developed and adopted by a number of global organizations as a basis for categorization of projects and determining the level of competence required to manage them. Based on this categorization, two levels of Project Manager Standards, Global Level 1 and Global Level 2, were released in 2006.20 These are being used and adapted by organizations often in association with the knowledge based standards of the various professional associations as a basis for determining competence, based on evidence of workplace application.

An important aspect of the work of the GAPPS is the mapping or benchmarking of standards for project management produced by a range of project management associations and governments. All output of the GAPPS is made freely available via their web-site (www.globalpmstandards.org).

One can only hope that the potential of this venture for global adoption will be realized, for the benefit of all in the project management field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author gratefully acknowledges the ready assistance of Dr. Lynn Crawford, who was particularly helpful in clarifying certain facts and interpretations.

REFERENCES

1 Project Management Institute, Project Management Body of Knowledge (Drexel Hill, Penn.: PMI 1987).

2 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, PMBOK® Guide, 2000 Edition, PMI, 2000; A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Third Edition, Project Management Institute, PMI, 2004; and A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition, Project Management Institute, PMI, 2008.

3 Harold Koontz and Cyril O’Donnell, Essentials of Management (New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill 1978).

4 PMI (1987), p. 3.

5 “Project Management Body of Knowledge: Special Summer Issue,” Project Management Journal 17, No. 3 (1986), p. 15.

6 “Ethics, Standards, Accreditation: Special Report,” Project Management Quarterly. PMI: Newtown Square, PA. August, 1983.

7 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition. PMI: Newtown Square, PA. (2008).

8 PMI 2000.

9 Peter W.G. Morris, “Updating the Project Management Bodies of Knowledge.” Project Management Journal (September 2001).

10 Association for Project Management, APM Body of Knowledge (5th Edition). APM: High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK (2006).

11 Morris, “Updating the Project Management Bodies of Knowledge.”

12 International Project Management Association, ICB: IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0. Nijkerk, The Netherlands: International Project Management Association (2006).

13 Project Management Association of Japan, P2M: Project and Program Management for Enterprise Innovation: Guidebook (Japan: PMAJ 2008).

14 L.H. Crawford, Global Body of Project Management Knowledge and Standards. In P.W.G. Morris & J.K. Pinto (Editors), The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects, Chapter 46. (Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

15 L. Heywood, A Gonczi and P. Hager, A Guide to Development of Competency Standards for Professions: Research Paper 7 (Australia: National Office of Overseas Skills Recognition, Australian Government Publishing Service, April 1992).

16 Project Management Institute, Project Manager Competency Development Framework (Newtown Square, Penn.: PMI 2002).

17 Australian Institute of Project Management (Sponsor), National Competency Standards for Project Management (Sydney, Australia: AIPM 1996).

18 South African Qualifications Authority, Notice of Publication of Unit Standards-Based Qualifications for Public Comment: National Certificate in Project Management—NQF Level 4. (South Africa: Government Gazette Vol. 437, No. 22846, 21st November 2001).

19 Association for Project Management. APM Competence Framework. High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK (2008).

20 Engineering Construction Industry Training Board, National Occupation Standards for Project Management (Kings Langley, UK; ECITB, 2002).

21 GAPPS A Framework for Performance Based Competency Standards for Global Level 1 and 2 Project Managers. Johannesburg, Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards (2006).