CHAPTER 12B

Studies in Project Human Resource Management

Leadership

More than any other organizational form, effective project management requires an understanding of motivational forces and leadership. The ability to build project teams, motivate people, and create organizational structures conducive to innovative and effective work requires sophisticated interpersonal and organizational skills.

There is no single magic formula for successful project management. However, most senior managers agree that effective management of multidisciplinary activities requires an understanding of the interaction of organizational and behavioral elements in order to build an environment conducive to the team’s motivational needs and subsequently lead effectively the complex integration of a project through its multifunctional phases.

MOTIVATIONAL FORCES IN PROJECT TEAM MANAGEMENT

Understanding people is important for the effective team management of today’s challenging projects. The breed of managers that succeeds within these often unstructured work environments faces many challenges. Internally, they must be able to deal effectively with a variety of interfaces and support personnel over whom they often have little or no control. Externally, managers have to cope with constant and rapid change regarding technology, markets, regulations, and socioeconomic factors. Moreover, traditional methods of authority-based direction, performance measures, and control are virtually impractical in such contemporary environments.

Sixteen specific professional needs of project team personnel are listed below. Research studies show that the fulfillment of these professional needs can drive project personnel to higher performance; conversely, the inability to fulfill these needs may become a barrier to teamwork and high project performance. The rationale for this important correlation is found in the complex interaction of organizational and behavioral elements. Effective team management involves three primary issues: (1) people skills, (2) organizational structure, and (3) management style. All three issues are influenced by the specific task to be performed and the surrounding environment. That is, the degree of satisfaction of any of the needs is a function of (1) having the right mix of people with appropriate skills and traits, (2) organizing the people and resources according to the tasks to be performed, and (3) adopting the right leadership style.1 The sixteen specific professional needs of team personnel are as follows:

1. Interesting and challenging work. Interesting and challenging work satisfies various professional esteem needs. It is oriented toward intrinsic motivation of the individual and helps to integrate personal goals with the objectives of the organization.

2. Professionally stimulating work environment. This leads to professional involvement, creativity, and interdisciplinary support. It also fosters team building and is conducive to effective communication, conflict resolution, and commitment toward organizational goals. The quality of this work environment is defined through its organizational structure, facilities, and management style.

3. Professional growth. Professional growth is measured by promotional opportunities, salary advances, the learning of new skills and techniques, and professional recognition. A particular challenge exists for management in limited-growth or zero-growth businesses to compensate for the lack of promotional opportunities by offering more intrinsic professional growth in terms of job satisfaction.

4. Overall leadership. This involves dealing effectively with individual contributors, managers, and support personnel within a specific functional discipline as well as across organizational lines. It involves technical expertise, information-processing skills, effective communications, and decision-making skills. Taken together, leadership means satisfying the need for clear direction and unified guidance toward established objectives.

5. Tangible records. These include salary increases, bonuses, and incentives, as well as promotions, recognition, better offices, and educational opportunities. Although extrinsic, these financial rewards are necessary to sustain strong long-term efforts and motivation. Furthermore, they validate more intrinsic rewards such as recognition and praise and reassure people that higher goals are attainable.

6. Technical expertise. Personnel need to have all necessary interdisciplinary skills and expertise available within the project team to perform the required tasks. Technical expertise includes understanding the technicalities of the work, the technology and underlying concepts, theories and principles, design methods and techniques, and functioning and interrelationship of the various components that make up the total system.

7. Assisting in problem solving. Assisting in problem solving, such as facilitating solutions to technical, administrative, and personal problems, is a very important need. If not satisfied, it often leads to frustration, conflict, and poor quality work.

8. Clearly defined objectives. Goals, objectives, and outcomes of an effort must be clearly communicated to all affected personnel. Conflict can develop over ambiguities or missing information.

9. Management control. Management control is important for effective team performance. Managers must understand the interaction of organizational and behavior variables in order to exert the direction, leadership, and control required to steer the project effort toward established organizational goals without stifling innovation and creativity.

10. Job security. This is one of the very fundamental needs that must be satisfied before people consider higher-order growth needs.

11. Senior management support. Senior management support should be provided in four major areas: (1) financial resources, (2) effective operating charter, (3) cooperation from support departments, and (4) provision of necessary facilities and equipment. It is particularly crucial to larger, more complex undertakings.

12. Good interpersonal relations. These are required for effective teamwork since they foster a stimulating work environment with low conflict, high productivity, and involved, motivated personnel.

13. Proper planning. Proper planning is absolutely essential for the successful management of multidisciplinary activities. It requires communications and information-processing skills to define the actual resource requirements and administrative support necessary. It also requires the ability to negotiate resources and commitment from key personnel in various support groups across organizational lines.

14. Clear role definition. This helps to minimize role conflict and power struggles among team members and/or supporting organizations. Clear charters, plans, and good management direction are some of the powerful tools used to facilitate clear role definitions.

15. Open communications. This satisfies the need for a free flow of information both horizontally and vertically. It keeps personnel informed and functions as a pervasive integrator of the overall project effort.

16. Minimizing changes. Although project managers have to live with constant change, their team members often see change as an unnecessary condition that impedes their creativity and productivity. Advanced planning and proper communications can help to minimize changes and lessen their negative impact.

THE POWER SPECTRUM IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Project managers must often cross functional lines to get the required support. This is especially true for managers who operate within a matrix structure. Almost invariably, the manager must build multidisciplinary teams into cohesive work groups and successfully deal with a variety of interfaces, such as functional departments, staff groups, other support groups, clients, and senior management. This is a work environment where managerial power is shared by many individuals. In the traditional organization, position power is provided largely in the form of legitimate authority, reward, and punishment. These organizationally derived bases of influence are shown in Table 12B-1. In contrast, project managers have to build most of their power bases on their own. They have to earn their power and influence from other sources. Trust, respect, credibility, and the image of a facilitator of a professionally stimulating work environment are the makings of this power and influence. These individually derived bases of influence are also shown in Table 12B-1.

In today’s environment, most project management is largely characterized by:

• Authority patterns that are defined only in part by formal organization chart plans.

• Authority that is largely perceived by the members of the organization based on earned credibility, expertise, and perceived priorities.

• Dual accountability of most personnel, especially in project-oriented environments.

• Power that is shared between resource managers and project/task managers.

• Individual autonomy and participation that is greater than in traditional organizations.

• Weak superior-subordinate relationships in favor of stronger peer relationships.

• Subtle shifts of personnel loyalties from functional to project lines.

• Project performance that depends on teamwork.

• Group decision making that tends to favor the strongest organizations.

• Reward and punishment power along both vertical and horizontal lines in a highly dynamic pattern.

TABLE 12B-1. THE PROJECT MANAGER’S BASES OF INFLUENCE

• Influences to reward and punish that come from many organizations and individuals.

• Multiproject involvement of support personnel and sharing of resources among many activities.

Position power is a necessary prerequisite for effective project/team leadership. Like many other components of the management system, leadership style has also undergone changes over time. With increasing task complexity and an increasingly dynamic organizational environment, a more adaptive and skill-oriented management style has evolved. This style complements the organizationally derived power bases—such as authority, reward, and punishment—with bases developed by the individual manager. Examples of these individually derived components of influence are technical and managerial expertise, friendship, work challenge, promotional ability, fund allocations, charisma, personal favors, project goal indemnification, recognition, and visibility. This so-called Style II management evolved particularly with the matrix. Effective project management combines both the organizationally derived and individually derived styles of influence.

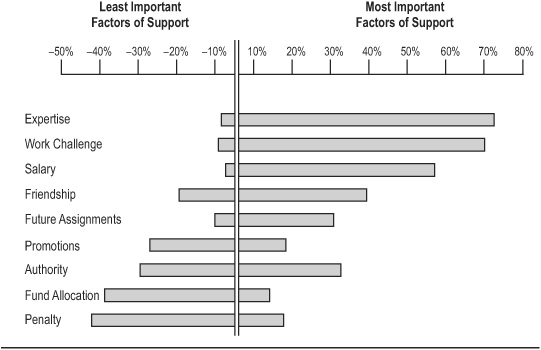

Various research studies by Gemmill, Thamhain, and Wilemon provide an insight into the power spectrum available to project managers.2 Project personnel were asked to rank nine influence bases; Table 12B-2 shows the results. Technical and managerial expertise, work challenge, and influence over salary were the most important influences that project leaders seem to have, while penalty factors, fund allocations, and authority appeared least important in gaining support from project team members. Moreover, the trend represented in these studies, toward the greater influence of expertise and work satisfaction, continues to strengthen as Gen X and Y individuals bring their particular worldview to bear in the work place.

TABLE 12B-2. THE PROJECT MANAGER’S POWER SPECTRUM

LEADERSHIP STYLE EFFECTIVENESS

For more than 15 years, the author has investigated influence bases with regard to project management effectiveness.3 Through those formal studies it is measurably and consistently found that managers who are perceived by their personnel as (1) emphasizing work challenge and expertise, but (2) deemphasizing authority, penalty, and salary, foster a climate of good communications, high involvement, and strong support to the tasks at hand. Ultimately, this style results in high performance ratings by upper management.

The relationship of managerial influence, style, and effectiveness has been statistically measured.4 One of the most interesting findings is the importance of work challenge as an influence method. Work challenge appears to integrate the personal goals and needs of personnel with organizational goals. That is, work challenge is primarily oriented toward extrinsic rewards with less regard to the personnel’s profressional needs. Therefore, enriching the assignments of team personnel in a professionally challenging way may indeed have a beneficial effect on overall performance. In addition, the assignment of challenging work is a variable over which project managers may have a great deal of control. Even if the total task structure is fixed, the method by which work is assigned and distributed is discretionary in most cases.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EFFECTIVE PROJECT TEAM MANAGEMENT

The project leader must foster an environment where team members are professionally satisfied, are involved, and have mutual trust. By contrast, when a team member does not feel part of the team and does not trust others, information is not shared willingly or openly. One project leader emphasized the point: “There’s nothing worse than being on a team where no one trusts anyone else. Such situations lead to gamesmanship and a lot of watching what you say because you don’t want your own words to bounce back in your own face.”

Furthermore, the greater the team spirit and trust and the quality of information exchange among team members, the more likely the team will be able to develop effective decision-making processes, make individual and group commitment, focus on problem solving, and develop self-forcing, self-correcting project controls. These are the characteristics of an effective and productive project team. A number of specific recommendations are listed below for project leaders and managers responsible for the integration of multidisciplinary tasks to help in their complex efforts of building high-performing project teams.

![]() Recognize barriers. Project managers must understand the various barriers to team development and build a work environment conducive to the team’s motivational needs. Specifically, management should try to watch out for the following barriers: (1) unclear objectives, (2) insufficient resources and unclear findings, (3) role conflict and power struggle, (4) uninvolved and unsupportive management, (5) poor job security, and (6) shifting goals and priorities.

Recognize barriers. Project managers must understand the various barriers to team development and build a work environment conducive to the team’s motivational needs. Specifically, management should try to watch out for the following barriers: (1) unclear objectives, (2) insufficient resources and unclear findings, (3) role conflict and power struggle, (4) uninvolved and unsupportive management, (5) poor job security, and (6) shifting goals and priorities.

![]() Define clear project objectives. The project objectives and their importance to the organization should be clear to all personnel involved with the project. Senior management can help develop a “priority image” and communicate the basic project parameters and management guidelines.

Define clear project objectives. The project objectives and their importance to the organization should be clear to all personnel involved with the project. Senior management can help develop a “priority image” and communicate the basic project parameters and management guidelines.

![]() Assure management commitment. A project manager must continually update and involve management to refuel its interests in and commitments to the new project. Breaking the project into smaller phases and being able to produce short-range results are important to this refueling process.

Assure management commitment. A project manager must continually update and involve management to refuel its interests in and commitments to the new project. Breaking the project into smaller phases and being able to produce short-range results are important to this refueling process.

![]() Build a favorable image. Building a favorable image for the project in terms of high priority, interesting work, importance to the organization, high visibility, and potential for professional rewards is crucial to the ability to attract and hold high-quality people. It is also a pervasive process that fosters a climate of active participation at all levels; it helps to unify the new project team and minimize dysfunctional conflict.

Build a favorable image. Building a favorable image for the project in terms of high priority, interesting work, importance to the organization, high visibility, and potential for professional rewards is crucial to the ability to attract and hold high-quality people. It is also a pervasive process that fosters a climate of active participation at all levels; it helps to unify the new project team and minimize dysfunctional conflict.

![]() Manage and lead. Leadership positions should be carefully defined and staffed at the beginning of a new program. Key project personnel selection is the joint responsibility of the project manager and functional management. The credibility of the project leader among team members with senior management and with the program sponsor is crucial to the leader’s ability to manage multidisciplinary activities effectively across functional lines. One-on-one interviews are recommended for explaining the scope and project requirement, as well as the management philosophy, organizational structure, and rewards.

Manage and lead. Leadership positions should be carefully defined and staffed at the beginning of a new program. Key project personnel selection is the joint responsibility of the project manager and functional management. The credibility of the project leader among team members with senior management and with the program sponsor is crucial to the leader’s ability to manage multidisciplinary activities effectively across functional lines. One-on-one interviews are recommended for explaining the scope and project requirement, as well as the management philosophy, organizational structure, and rewards.

![]() Plan and define your project. Effective planning early in the project life cycle has a favorable impact on the work environment and team effectiveness. This is especially so because project managers have to integrate various tasks across many functional lines. Proper planning, however, means more than just generating the required pieces of paper. It requires the participation of the entire project team, including support departments, subcontractors, and management. These planning activities—which can be performed in a special project phase such as requirements analysis, product feasibility assessment, or product/project definition—usually have a number of side benefits besides generating a comprehensive road map for the upcoming program.

Plan and define your project. Effective planning early in the project life cycle has a favorable impact on the work environment and team effectiveness. This is especially so because project managers have to integrate various tasks across many functional lines. Proper planning, however, means more than just generating the required pieces of paper. It requires the participation of the entire project team, including support departments, subcontractors, and management. These planning activities—which can be performed in a special project phase such as requirements analysis, product feasibility assessment, or product/project definition—usually have a number of side benefits besides generating a comprehensive road map for the upcoming program.

![]() Create involvement. One of the side benefits of proper planning is the involvement of personnel at all organizational levels. Project managers should drive such an involvement, at least with their key personnel, especially during the project definition phases. This involvement leads to a better understanding of the task requirements, stimulates interest, helps unify the team, and ultimately leads to commitment to the project plan regarding technical performance, timing, and budgets.

Create involvement. One of the side benefits of proper planning is the involvement of personnel at all organizational levels. Project managers should drive such an involvement, at least with their key personnel, especially during the project definition phases. This involvement leads to a better understanding of the task requirements, stimulates interest, helps unify the team, and ultimately leads to commitment to the project plan regarding technical performance, timing, and budgets.

![]() Assure proper project staffing. All project assignments should be negotiated individually with each prospective team member. Each task leader should be responsible for staffing his or her own task team. Where dual-reporting relationships are involved, staffing should be conducted jointly by the two managers. The assignment interview should include a clear discussion of the specific tasks, outcome, timing, responsibilities, reporting relation, potential rewards, and importance of the project to the company. Task assignments should be made only if the candidate’s ability is a reasonable match to the position requirements and the candidate shows a healthy degree of interest in the project.

Assure proper project staffing. All project assignments should be negotiated individually with each prospective team member. Each task leader should be responsible for staffing his or her own task team. Where dual-reporting relationships are involved, staffing should be conducted jointly by the two managers. The assignment interview should include a clear discussion of the specific tasks, outcome, timing, responsibilities, reporting relation, potential rewards, and importance of the project to the company. Task assignments should be made only if the candidate’s ability is a reasonable match to the position requirements and the candidate shows a healthy degree of interest in the project.

![]() Define team structure. Management must define the basic team structure and operating concepts early during the project formation phase. The project plan, task matrix, project charter, and policy are the principal tools. It is the responsibility of the project manager to communicate the organizational design and to assure that all parties understand the overall and interdisciplinary project objectives. Clear and frequent communication with senior management and the new project sponsor is critically important. Status review meetings can be used for feedback.

Define team structure. Management must define the basic team structure and operating concepts early during the project formation phase. The project plan, task matrix, project charter, and policy are the principal tools. It is the responsibility of the project manager to communicate the organizational design and to assure that all parties understand the overall and interdisciplinary project objectives. Clear and frequent communication with senior management and the new project sponsor is critically important. Status review meetings can be used for feedback.

![]() Conduct team-building sessions. The project manager should conduct team-building sessions throughout the project life cycle. An especially intense effort might be needed during the team formation stage. The team should be brought together periodically in a relaxed atmosphere to discuss such questions as: (1) How are we operating as a team? (2) What is our strength? (3) Where can we improve? (4) What steps are needed to initiate the desired change? (5) What problems and issues are we likely to face in the future? (6) Which of these can be avoided by taking appropriate action now? (7) How can we “danger-proof” the team?

Conduct team-building sessions. The project manager should conduct team-building sessions throughout the project life cycle. An especially intense effort might be needed during the team formation stage. The team should be brought together periodically in a relaxed atmosphere to discuss such questions as: (1) How are we operating as a team? (2) What is our strength? (3) Where can we improve? (4) What steps are needed to initiate the desired change? (5) What problems and issues are we likely to face in the future? (6) Which of these can be avoided by taking appropriate action now? (7) How can we “danger-proof” the team?

![]() Develop your team continuously. Project leaders should watch for problems with changes in performance, and such problems should be dealt with quickly. Internal or external organization development specialists can help diagnose team problems and assist the team in dealing with the identified problems. These specialists also can bring fresh ideas and perspectives to difficult and sometimes emotionally complex situations.

Develop your team continuously. Project leaders should watch for problems with changes in performance, and such problems should be dealt with quickly. Internal or external organization development specialists can help diagnose team problems and assist the team in dealing with the identified problems. These specialists also can bring fresh ideas and perspectives to difficult and sometimes emotionally complex situations.

![]() Develop team commitment. Project managers should determine whether team members lack commitment early in the life of the project and attempt to change possible negative views toward the project. Since insecurity often is a major reason for lacking commitment, managers should try to determine why insecurity exists, and then work on reducing the team members’ fears. Conflict with other team members may be another reason for lack of commitment. If there are project professionals whose interests lie elsewhere, the project leader should examine ways to satisfy part of those members’ interests by bringing personal and project goals into perspective.

Develop team commitment. Project managers should determine whether team members lack commitment early in the life of the project and attempt to change possible negative views toward the project. Since insecurity often is a major reason for lacking commitment, managers should try to determine why insecurity exists, and then work on reducing the team members’ fears. Conflict with other team members may be another reason for lack of commitment. If there are project professionals whose interests lie elsewhere, the project leader should examine ways to satisfy part of those members’ interests by bringing personal and project goals into perspective.

![]() Assure senior management support. It is critically important for senior management to provide the proper environment for the project team to function effectively. The project leader needs to tell management at the outset of the program what resources are needed. The project manager’s relationship with senior management and ability to develop senior management support are critically affected by his or her credibility and visibility and the priority image of the project.

Assure senior management support. It is critically important for senior management to provide the proper environment for the project team to function effectively. The project leader needs to tell management at the outset of the program what resources are needed. The project manager’s relationship with senior management and ability to develop senior management support are critically affected by his or her credibility and visibility and the priority image of the project.

![]() Focus on problem avoidance. Project leaders should focus their efforts on problem avoidance. That is, the project leader, through experience, should recognize potential problems and conflicts before their onset and deal with them before they become big and their resolutions consume a large amount of time and effort.

Focus on problem avoidance. Project leaders should focus their efforts on problem avoidance. That is, the project leader, through experience, should recognize potential problems and conflicts before their onset and deal with them before they become big and their resolutions consume a large amount of time and effort.

![]() Show your personal drive and desire. Finally, project managers can influence the climate of their work environment by their own actions. Concern for project team members and ability to create personal enthusiasm for the project itself can foster a climate high in motivation, work involvement, open communication, and resulting project performance.

Show your personal drive and desire. Finally, project managers can influence the climate of their work environment by their own actions. Concern for project team members and ability to create personal enthusiasm for the project itself can foster a climate high in motivation, work involvement, open communication, and resulting project performance.

CONCLUSION

Effective team management is a critical determinant of project success. Building the group of project personnel into a cohesive, unified task team is one of the prime responsibilities of the program leader. Team building involves a whole spectrum of management skills to identify, commit, and integrate the various personnel from different functional organizations. Team building is a shared responsibility between the functional managers and the project manager, who often reports to a different organization with a different superior.

To be effective, the project manager must provide an atmosphere conducive to teamwork. Four major considerations are involved in the integration of people from many disciplines into an effective team: (1) creating a professionally stimulating work environment, (2) ensuring good program leadership, (3) providing qualified personnel, and (4) providing a technically and organizationally stable environment. The project leader must foster an environment where team members are professionally satisfied, involved, and have mutual trust. The more effectively project leaders develop team membership, have a higher quality of information exchanged, and have a greater candor of team members. It is this professionally stimulating involvement that also has a pervasive effect on the team’s ability to cope with change and conflict and leads to innovative performance. By contrast, when a member does not feel part of the team and does not trust others, information is not shared willingly or openly.

Furthermore, the greater the team spirit, trust, and quality of information exchange among team members, the more likely the team is able to develop effective decision-making processes, make individual and group commitments, focus on problem solving, and develop self-enforcing, self-correcting project controls. These are the characteristics of an effective and productive project team.

To be successful, project leaders must develop their team management skills. They must have the ability to unify multifunctional teams and lead them toward integrated results. They must understand the interaction of organizational and behavioral elements in order to build an environment that satisfies the team’s motivational needs. Active participation, minimal interpersonal conflict, and effective communication are some of the major factors that determine the quality of the organization’s environment.

Furthermore, project managers must provide a high degree of leadership in unstructured environments. They must develop credibility with peer groups, team members, senior management, and customers. Above all, the project manager must be a social architect who understands the organization and its culture, value system, environment, and technology. These are the prerequisites for moving project-oriented organizations toward long-range productivity and growth.

REFERENCES

1 H. Barkema, J. Baum, and E. Mannix, “Management Challenges in a New Time,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. 5 (2002), pp. 916–930; K. English, “The Changing Landscape of Leadership,” Research Technology Management, Vol. 45, No. 4 (Jul/Aug 2004), p. 9; C. Feld, “Getting it Right,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, No. 2 (February 2004), pp. 72–79; A. Parker, “What Creates Energy in Organizations?” MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Summer 2003), pp. 51–60; R. Rodriguez, M. Green, and M. Ree, “Leading Generation X: Do the Old Rules Apply?” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Spring 2003), p. 67.

2 G. Gemmill and D. Wilemon, “The Hidden Side of Leadership in Technical Team Management,” Research Technology Management, Vol. 37, No. 6 (Nov/Dec 1994), pp. 25–33; H. Thamhain and D. Wilemon, “Building Effective Teams for Complex Project Environments,” Technology Management, Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 1999), pp. 203–212; H. Thamhain, “Leading Technology Teams,” Project Management Journal, Vol. 35, No. 4 (December 2004), pp. 35–47.

3 I. Kruglianskas, and H. Thamhain, “Managing Technology-Based Projects in Multinational Environments,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 47, No. 1 (February 2000), pp 55–64: H. Thamhain, “Working with Project Teams,” Chapter 18 in Project Management: Strategic Design and Implementation, D. Cleland and W. Ireland, eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002); H. Thamhain, “Managing Innovative R&D Teams,” R&D Management, Vol. 33, No. 3 (June 2003), pp. 297–312; H. Thamhain, “Managing Product Development Project Teams,” Chapter 9, pp. 127–143; PDMA Handbook of New Product Development, Kenneth Khan, Editor (New York: Wiley & Sons., 2005).

4 H. Thamhain, Management of Technology, (New York: Wiley & Sons, 2005), Chapter 5; H. Thamhain, and D. Wilemon, “Leadership, Conflict, and Project Management Effectiveness,” Executive Bookshelf on Generating Technological Innovations, Sloan Management Review (Fall 1987), pp. 68–87; H. Thamhain, “Linkages of Project Environment to Performance: Lessons for Team Leadership,” International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 22, No. 7 (October 2004), pp. 90–102.