CHAPTER 17

Competency and Careers in Project Management

Research into the causes of project failures has identified a primary cause of troubled or unsuccessful projects: the lack of qualified project managers.1 At one time, this lack was primarily due to the fact that qualified project managers were, in fact, quite rare. Project management was “the accidental profession,” not one for which people chose and trained.

Today, with the proliferation of degree programs, training courses, and a growing professional body, this is less true. The problem facing projects now is an organizational one. In many organizations, employees have very little incentive to assume the position of project manager, largely because of a disconnect surrounding what the role entails. Organizations have historically assumed that technical capabilities of individuals could be translated into project management expertise. Because of this, professionals who have worked for years to earn the title of senior engineer or technical specialist have been unwilling to exchange their current jobs for the role of project manager. The role is added to their regular job description, instead of being viewed as a legitimate function to be valued by the organization, and which requires a special set of skills. Therefore, many organizations still haven’t connected the value of the project manager to the success of the organization.

A second, related reason is that poor role definition—for all the roles in a project, but especially for the project manager—places even qualified personnel into situations where they are doomed to failure by requiring them to do too much and be expert in everything.

Clearly it’s time for organizations to become more systematic in the way they deal with the human resource challenges posed by the project environment. To explore a framework for the division of labor on projects that we think works both for the people and for the project outcomes, let’s start by examining the historical role of the project manager.

WHAT DOES A PROJECT MANAGER DO?

The project manager’s challenge is to combine two discrete areas of competence:

![]() The art of project management—Effective communications, trust, values, integrity, honesty, sociability, leadership, staff development, flexibility, decision making, perspective, sound business judgment, negotiations, customer relations, problem solving, managing change, managing expectations, training, mentoring, and consulting.

The art of project management—Effective communications, trust, values, integrity, honesty, sociability, leadership, staff development, flexibility, decision making, perspective, sound business judgment, negotiations, customer relations, problem solving, managing change, managing expectations, training, mentoring, and consulting.

![]() The science of project management—Plans, WBS, Gantt charts, standards, CPM/precedence diagrams, controls variance analysis, metrics, methods, earned value, s-curves, risk management, status reporting, resource estimating, and leveling.

The science of project management—Plans, WBS, Gantt charts, standards, CPM/precedence diagrams, controls variance analysis, metrics, methods, earned value, s-curves, risk management, status reporting, resource estimating, and leveling.

Because of the nature of the enterprises that were early adopters of project management (military, utility, construction industries), the profession “grew up” in an environment with a strong cost accounting view and developed a focus on project planning and controls—an emphasis on the science. This is the kind of project management that we think of as being “traditional” or “classic” project management. However, it simply represents an early evolutionary stage in the life of the discipline.

Since then, we have seen the emergence of countless trends. Project management is being used in nearly all industries and across all functions within those industries. Organizations have flattened out, matrixed organizations have taken root, and new information technology has allowed people to communicate more effectively and reduce cycle times across all business processes. As a result, management began pushing more projects onto an increasingly complex organization. The role of project manager is now very demanding and requires an ever-expanding arsenal of skills, especially “soft” or interpersonal skills.

What Makes a Good Project Manager?

The debate about project manager skills and competencies is well into its third decade. Thus, we have lists compiled by a dozen or so organizations, academics, and consultancies expressing views on “the good project manager.” What project manager skills, competencies, and characteristics do these lists agree on?

Technical or Industry Expertise

A baseline of technical or industry knowledge is what gets a project manager candidate in the door. Commonly, a project manager has an undergraduate degree in some technical specialty—and while that can mean engineering or computer science, with the broadening of the project management field, it can also mean a degree in marketing or one of the helping professions (e.g., health care, social work, education, law). Industry knowledge gained from work in a particular field, such as construction, information technology, or health care, is added to that baseline. Into this category also fall the technical aspects of project management: facility with project management software tools, for example.

Interpersonal and General Management Skills

But the bulk of the skills required—the skills upon which the role seems to succeed or fail—are those that are variously termed “Organization and People Competencies” (Association for Project Management, UK), “Personal Competencies” (PMI), or “High Performance Work Practices” (Academy of Management Journal, 1995). PMI’s list of project manager roles reads like a soft skills wish list: decision maker, coach, communication channel, encourager, facilitator, and behavior model.2 This last item was explored in research by Dr. Frank Toney of the University of Phoenix. In his book The Superior Project Manager, he states that “honesty” trumps education, experience, and even intelligence as a desirable quality in project managers.3

Thus, the “new project management” is characterized by a more holistic view of the project that goes beyond planning and controls to encompass business issues, human resource issues, organizational strategy portfolios, and marketing. The new project management places its focus on leadership and communication rather than a narrow set of technical tools, and advocates the use of the project management office in order to change corporate culture in a more project-oriented direction.

As a result, the role of the project manager has expanded in both directions: becoming more business- and leadership-oriented on one hand, while growing in technical complexity on the other. This puts both project managers and the organizations they serve in a bind. The title “project manager” often falls to an individual who carries a “kitchen-sink” job description that ranges from strategic and business responsibilities to paperwork to writing code: the “monster job.”

The solution to this problem is being worked out in many best-practice companies where the implementation of enterprise-level project management offices allows the development of specialized project roles and career paths. Our 2007 research study on the State of the PMO proved this by detailing an unprecedented rise in the number of enterprise project offices and the number of employees supervised within those PMOs. It also demonstrated that mature PMOs with large staffs of project managers and supporting project roles displayed better organizational performance.4 Best-practice companies define specific competencies for these roles, and provide “a fork in the road” that allows individuals who are gifted strongly either on the art side of the ledger—as program and project managers and mentors—to flourish, while allowing those whose skill lies in the science of project management to specialize in roles that provide efficiency in planning and controlling projects.

The Fork in the Road

Because the project leader has been found to be one of the most (if not the single most) critical factors to project success, much effort has been devoted to understanding what project managers can/should do to enhance the chances of project success. Leadership, communication, and networking skills top the list. In spite of the importance of leadership characteristics for project managers, researchers and practitioners have observed that project managers in many organizations are seen by senior management as implementers only.5

Confusion of roles and responsibilities would be averted if these two very different roles—leader and implementer—were not both referred to as “project managers.” Organizations can avoid this problem by determining beforehand who has the best mix of traits and skills to be a superior project manager, or the potential to become one, and by creating career paths for both technically oriented project managers and leadership-oriented project managers so that senior management can fully appreciate the breadth of the roles necessary to the effective management of projects. Technical project managers tend to focus more on process while business project managers are more concerned with business results. Ideally, a balance between the two is required, determined by the project type, organization culture, and systems.6

In addition, other roles can be broken out of the “monster” job description, further streamlining the leadership work of the project manager. Many tasks that have long been part of the project management landscape feature elements of administrative work, for example.7 In addition, project managers must be “grown” in the organization through a series of roles that develop the individual in positions of increasing responsibility: a career path.

IDENTIFYING AND ASSESSING COMPETENCY

One of the first things an organization must do is inventory the skills required for effective project management at all levels. After a skills inventory is developed, the key attributes of those skills must be determined and a profile developed. This is also the first step in developing competency requirements. Christopher Sauer, in his study of successful project-based organizations, points out that organizational capability is built from the ground up: by making it possible for the people who do projects to do their best.8 Focusing on building project manager competencies to the “best” level means first identifying what needs to be improved. To do this requires a competency assessment program.

Dimensions of Individual Competence

Competence may be described in different ways, but there are four dimensions that seem to be universally acknowledged:

Knowledge

For project managers, the “body of knowledge” contains more than simply specific knowledge about how to plan and control projects—the knowledge outlined in the PMBOK® Guide. There’s also knowledge in their chosen discipline (engineering, marketing, information systems, etc.) and knowledge of other disciplines that come into play in the industry in which they work, such as regulatory law or technology advancements; and knowledge of the business side (finance, personnel, strategic planning). Knowledge in all these areas can be built up through reading, classroom training, research on the Internet, and the kind of informal knowledge transfer that takes place constantly in the workplace and in professional associations.

Skills

For a project manager, skills may fall into any of three areas: their area of subject matter expertise (engineering, marketing, information systems); project management skills related to planning and controlling; or human skills (influencing, negotiating, communicating, facilitating, mentoring, coaching). The technical skills become less and less important as the project manager’s responsibility for the managerial skills grows; this is one reason why excellent technologists have often failed as project managers. As roles become more abstract—one of the hallmarks of knowledge work—the difficulty of defining the competencies necessary becomes complex. Skill at using a scheduling tool is easy to quantify; skill in strategic thinking, innovation, or teambuilding is much harder.

Personal Characteristics

On the intangible, but extremely important, side of the ledger, are things like energy and drive, enthusiasm, professional integrity, morale, determination, and commitment. In recent years, a number of project management writers have focused on these traits as being perhaps the most important for project managers, outweighing technical knowledge and skills. To focus on a few of these:

![]() Honesty. Project managers are role models for the entire project team. They must conduct themselves honestly and ethically to instill a sense of confidence, pride, loyalty, and trust throughout their project team. An honest and trustworthy project organization leads to greater efficiency, fewer risks, decreased costs, and improved profitability.

Honesty. Project managers are role models for the entire project team. They must conduct themselves honestly and ethically to instill a sense of confidence, pride, loyalty, and trust throughout their project team. An honest and trustworthy project organization leads to greater efficiency, fewer risks, decreased costs, and improved profitability.

![]() Ambition. Ambition is an important factor in business goal achievement. Project managers must be careful that their ambition doesn’t make them ruthless or selfish. They must use their determination to accomplish goals for the organization, as a whole, rather than for their own personal gain. However, achievement orientation, as defined in the ground-breaking work on motivation by David McClelland, comprises a focus on excellence, results orientation, innovation and initiative, and a bias toward action, and is very desirable in project managers.9

Ambition. Ambition is an important factor in business goal achievement. Project managers must be careful that their ambition doesn’t make them ruthless or selfish. They must use their determination to accomplish goals for the organization, as a whole, rather than for their own personal gain. However, achievement orientation, as defined in the ground-breaking work on motivation by David McClelland, comprises a focus on excellence, results orientation, innovation and initiative, and a bias toward action, and is very desirable in project managers.9

![]() Confidence. Leaders who are confident in their decisions are most likely to succeed. The most confident project managers believe that they have full control of their actions and decisions, versus the belief that outcomes are due to luck, fate, or chance. Superior project managers are confident in their decisions, proactive rather than reactive, and assume ownership for their actions and any consequences.

Confidence. Leaders who are confident in their decisions are most likely to succeed. The most confident project managers believe that they have full control of their actions and decisions, versus the belief that outcomes are due to luck, fate, or chance. Superior project managers are confident in their decisions, proactive rather than reactive, and assume ownership for their actions and any consequences.

Experience

When knowledge can be applied to practice, and skills polished, experience is gained. Experience also increases knowledge and skill. Experience can be gained in the workplace, or as a result of volunteer activities.

COMPETENCY MODELS

The first step toward competency-based management is to understand the patterns that are repeated by the most effective employees in their knowledge, skills, and behaviors—in other words, competencies that enable them to be high performers. This “architecture” of effectiveness for a given position is a competency model.10 A competency model comprises a list of differentiating competencies for a role or job family, the definition of each competency, and the descriptors or behavioral indicators describing how the competency is displayed by high performers. There are two types of competency models:

![]() Descriptive competency models define the knowledge, skills, and behaviors known to differentiate high performance from average performance in the current environment or recent past. Descriptive models can have high validity because they are built from actual data about the difference between average and star performers.

Descriptive competency models define the knowledge, skills, and behaviors known to differentiate high performance from average performance in the current environment or recent past. Descriptive models can have high validity because they are built from actual data about the difference between average and star performers.

![]() Prescriptive models lean toward describing competencies that will be important in the future. They are helpful in dynamic environments or to help drive a major change in culture or capabilities.

Prescriptive models lean toward describing competencies that will be important in the future. They are helpful in dynamic environments or to help drive a major change in culture or capabilities.

The best competency models combine features from each category.

Models for Project Management

Within the last decade, research attention has been focused on identifying competencies for project managers. The seminal work in this field was done by the Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM), whose National Competency Standard for Project Management was adopted by the Australian Government as part of that country’s national qualification system. In England, the Association for Project Management (APM) created competency standards for project controls specialists and project managers. The publication of the U.S.-based PMI’s competency standard in 2002,11 after five years of developmental work, established another framework for thinking about the components of competence in a project management context. The existence of project manager competency models streamlines the adoption of competency-based management for project-oriented companies. Although all these assessment frameworks are quite different, they do have certain themes in common.

From our point of view, a project manager competency assessment should determine who has the best mix of traits and skills to be a superior project manager, or the potential to become one.

Once competencies are defined, it is time to conduct an assessment of the identified project management populations. The assessment process should be clearly focused on building strengths, not on eliminating staff; mitigating fear of assessments through open communication is critical.

Let’s look at one model in detail: The Project Manager Competency Assessment Program (PMCAP) co-developed by PM College and Caliper International, a human resources assessment firm.12

Like other competency assessment systems, the PMCAP has three components: a multilevel knowledge test, a personality and cognitive assessment, and a multirater survey reviewing the current workplace performance of project managers. These three instruments address three aspects of competence: Knowledge of project management concepts, terminology, and theories; behavior and performance in the workplace; and personal traits indicative of the individual’s project manager potential. Thus it is both descriptive and prescriptive.

![]() Knowledge. The Knowledge Assessment Tool tests the candidate’s working knowledge of the language, concepts, and practices of the profession with questions based on the Project Management Institute’s PMBOK® Guide, the ISO-approved industry standard.13 On an individual basis, candidates can see how they scored on each knowledge area, how they compared to the highest score, their percentile ranking, and how many areas they passed. For the organization, an aggregate table provides insight into the areas that need improvement for their entire population. This information is used to begin developing a targeted education and training program designed to meet those needs.

Knowledge. The Knowledge Assessment Tool tests the candidate’s working knowledge of the language, concepts, and practices of the profession with questions based on the Project Management Institute’s PMBOK® Guide, the ISO-approved industry standard.13 On an individual basis, candidates can see how they scored on each knowledge area, how they compared to the highest score, their percentile ranking, and how many areas they passed. For the organization, an aggregate table provides insight into the areas that need improvement for their entire population. This information is used to begin developing a targeted education and training program designed to meet those needs.

![]() Behavioral Assessment. A second area of assessment is in behaviors exhibited in the workplace. This requires the use of a multirater tool (sometimes called a 360-degree tool), which allows the acquisition of feedback on the project managers’ behavior from a variety of sources—typically peers, subordinates, supervisors, and/or clients, but always someone who has first-hand knowledge of the candidate’s behavior in the workplace. For example, it might examine the creation of a stakeholder communication plan, the development and distribution of a team charter, or the execution of a risk management plan. Individuals rate themselves on their competency in several key performance indicators. The independent assessors then rate the individuals on those same criteria. Ratings are compared. A multirater assessment provides holistic view of the individual’s project manager behaviors and serves as a gauge for determining which behaviors demonstrate areas for potential growth.

Behavioral Assessment. A second area of assessment is in behaviors exhibited in the workplace. This requires the use of a multirater tool (sometimes called a 360-degree tool), which allows the acquisition of feedback on the project managers’ behavior from a variety of sources—typically peers, subordinates, supervisors, and/or clients, but always someone who has first-hand knowledge of the candidate’s behavior in the workplace. For example, it might examine the creation of a stakeholder communication plan, the development and distribution of a team charter, or the execution of a risk management plan. Individuals rate themselves on their competency in several key performance indicators. The independent assessors then rate the individuals on those same criteria. Ratings are compared. A multirater assessment provides holistic view of the individual’s project manager behaviors and serves as a gauge for determining which behaviors demonstrate areas for potential growth.

![]() Potential. The potential to perform the project manager role is evaluated through a series of questions that test the ability to solve problems, handle stress, be flexible, negotiate, deal with corporate politics, manage personal time, and manage conflict. The candidate’s score is compared to high performers (project managers who show the highest level of competency). The results of this assessment indicate an individual’s potential to survive and thrive in the role of a project manager.

Potential. The potential to perform the project manager role is evaluated through a series of questions that test the ability to solve problems, handle stress, be flexible, negotiate, deal with corporate politics, manage personal time, and manage conflict. The candidate’s score is compared to high performers (project managers who show the highest level of competency). The results of this assessment indicate an individual’s potential to survive and thrive in the role of a project manager.

Project Manager Competencies

According to research conducted by PM College in conjunction with Caliper, 70 percent of the competencies of a project manager overlap with the competencies of a typical mid-level functional manager. These competencies can be summarized as:

![]() Leadership. This is usually characterized by a sense of ownership and sense of mission, a long-term perspective, assertiveness, and a managerial orientation. Leaders focus on developing people, creatively challenging the system, and inspiring others to act.

Leadership. This is usually characterized by a sense of ownership and sense of mission, a long-term perspective, assertiveness, and a managerial orientation. Leaders focus on developing people, creatively challenging the system, and inspiring others to act.

![]() Communication. This includes written and oral communication, as well as listening skills, and competent use of all available communication tools. Understanding communication differences, and not letting them become a barrier to project success, is key to clearly delegate responsibilities and instructions to the project team. Project managers also must serve as liaisons between project teams and executive teams. Skilled project managers know when to speak, when to listen, and how to resolve issues and conflicts in a calm and professional manner. A related skill, negotiation, is a daily feature of the project manager’s life. Among the issues that must be negotiated with clients, executives, contractors, functional managers and team members are scope, changes, contracts, assignments, resources, personnel issues, and conflict resolution.

Communication. This includes written and oral communication, as well as listening skills, and competent use of all available communication tools. Understanding communication differences, and not letting them become a barrier to project success, is key to clearly delegate responsibilities and instructions to the project team. Project managers also must serve as liaisons between project teams and executive teams. Skilled project managers know when to speak, when to listen, and how to resolve issues and conflicts in a calm and professional manner. A related skill, negotiation, is a daily feature of the project manager’s life. Among the issues that must be negotiated with clients, executives, contractors, functional managers and team members are scope, changes, contracts, assignments, resources, personnel issues, and conflict resolution.

![]() Problem Solving Skills. These include proactive information gathering/strategic inquiry (this goes hand in hand with the “bias for action”—project managers actively seek out information that might impact the project instead of waiting for it to surface, and apply that information in creative ways); systematic/systemic thinking—project managers must be able to both focus on the details of a problem and see it in the context of the larger organizational or business issues.

Problem Solving Skills. These include proactive information gathering/strategic inquiry (this goes hand in hand with the “bias for action”—project managers actively seek out information that might impact the project instead of waiting for it to surface, and apply that information in creative ways); systematic/systemic thinking—project managers must be able to both focus on the details of a problem and see it in the context of the larger organizational or business issues.

![]() Self-Assessment/Mastery. Best practices project managers are able to consider their actions in a variety of situations and critically evaluate their own performance. This introspective ability enables the great project managers to adjust for mistakes, adapt for differences in team personalities, and remold their approaches to maximize team output.14

Self-Assessment/Mastery. Best practices project managers are able to consider their actions in a variety of situations and critically evaluate their own performance. This introspective ability enables the great project managers to adjust for mistakes, adapt for differences in team personalities, and remold their approaches to maximize team output.14

![]() Influencing ability. This is the ability to influence others’ decisions and opinions through reason and persuasion, the strategic and political awareness and the relationship development skills that are the basis for influence, and the ability to get things done in an organizational context.15

Influencing ability. This is the ability to influence others’ decisions and opinions through reason and persuasion, the strategic and political awareness and the relationship development skills that are the basis for influence, and the ability to get things done in an organizational context.15

Gap analysis is the next step after assessment of competency. The knowledge gaps are determined by examining the differences between the demonstrated level of knowledge and the level of knowledge that is required. The behavioral gaps are identified by examining the differences between the self-rating of the project manager candidate and the rater’s score. The gaps in both knowledge and behavior, based on the size of the gap, are targeted as developmental opportunities. The results of this integrated assessment are used to create professional development plans for project manager candidates.

While an individual assessment is being conducted, the organization should be determining what roles they will need to ensure an improved level of project performance. Possible roles include team leaders, multiple levels of project managers, program managers, project portfolio managers, project executives, project office directors, and chief project officers. With each of these roles, the organization will need to create effective job/role descriptions that define performance/competency expectations, experiential requirements, and prerequisites of whatever technical skills are required.16,17,18

As project managers expand into new industries, additional areas of competency will emerge. The project manager’s role is evolving away from technical, tool-based project management (especially in knowledge-based organizations such as R&D), and towards a broader “art” of leadership. But that doesn’t mean the science can be left behind. Equally as important are the competencies that many companies are successfully sorting into a new “starring role”: the Project Planner.

The Emergence of the Project Planner Role

A project planner supports the project manager by taking over critical, detail-oriented, time-intensive tasks, such as the ones discussed above. As a result, the project manager is free to focus on more strategic project goals and objectives. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the core tasks of the leader. It’s worthwhile noting that the core tasks of the manager have been identified as:

• Planning the work.

• Organizing the work.

• Implementing the plan.

• Controlling results.

These tasks align with the role of planner. Together, the project manager and planner/controller resolve the leader/manager dilemma by supplying both aspects of these roles in collaboration.

What Makes a Good Project Planner?

To efficiently handle the responsibilities outlined above, the successful project controller/planner must possess technical expertise in project management software and related spreadsheet and/or database (financial, resource) tools, as well as business process expertise in cost budgeting and estimating, risk analysis, critical path diagramming and analysis, resource forecasting, and change control. In contrast to the project manager candidate, the ideal project planner has the following personal and professional characteristics:

• Logical thinker and problem solver

• Organized and detail-focused

• Numbers-oriented

• Ability to interpret complicated and interconnected data

• Communication skills, especially as they apply to project information

• PM software expertise

• Application software expertise (accounting, procurement, etc.).

Just as with project managers of varying experience and skill, you’ll find a hierarchy in the project planning and controls arena. A serious project controls person will have a breadth of experience that encompasses many of what we have termed “specialty areas,” like change (configuration) control, risk management (from the perspective of quantifying risks with the tools), issues management, action item tracking, multiproject reporting, executive reporting, scheduling integration, organizational resource management, multiproject resource analysis, forecasting, leveling, multiproject what-if analysis, management of the organizational (enterprise) resource library, schedule estimating, cost estimating, etc. And, just as with project managers, the organization will benefit from establishing a career path from the specialist team member level to a sophisticated divisional project controls position.

One insurance executive characterized the roles relationships in this way:

We like to think of the project manager as the CEO of the project, and the project planner as the CFO. Like the CEO and CFO, both the project manager and project planner carry out crucial duties, and both need to possess significant, albeit different, skill sets and experiences in order to bring the projects in on time, within budget, and at agreed quality levels.19

Project Team Members: Specialty Roles in Project Management

The team member position is where the actual day-to-day work of the project planning, estimating, statusing, and analysis is done. Within this level, more definitive project management roles—depending on the organization—can include: Project Controllers, Project Analysts, Schedulers, Business Analysts, Estimators, and Systems Analysts. In addition, there are some new, evolving specialty roles, such as:

![]() Knowledge Management Coordinator. Sometimes formerly known as the “librarian,” this role has grown to include the maintenance of project records, standards, methods, and lessons learned, all of which must be stored in a project database/repository. In a large organization, the maintenance of such a repository can develop into a full-time job. Once envisioned as a clerical task, the SPO librarian is now evolving into a sophisticated knowledge-management function and will become a be a fruitful source of benefits and value to the entire organization for historical data, successful practices, and effective templates, with knowledge that was previously lost with changes in and transitions of personnel.

Knowledge Management Coordinator. Sometimes formerly known as the “librarian,” this role has grown to include the maintenance of project records, standards, methods, and lessons learned, all of which must be stored in a project database/repository. In a large organization, the maintenance of such a repository can develop into a full-time job. Once envisioned as a clerical task, the SPO librarian is now evolving into a sophisticated knowledge-management function and will become a be a fruitful source of benefits and value to the entire organization for historical data, successful practices, and effective templates, with knowledge that was previously lost with changes in and transitions of personnel.

![]() Methodologist. Best practice or process experts, they provide training, project oversight, quality assurance, and methodology development.

Methodologist. Best practice or process experts, they provide training, project oversight, quality assurance, and methodology development.

![]() Resource Manager. In organizations with significant project activity, the responsibility for resource management may become a full-time job. One major insurance company titles this role the “Project Manager Role Steward.” Individual project managers, rather than having to “beg, borrow, and steal” resources wherever they can find them, turn to the resource manager for assistance. The RM prioritizes resource requests, manages the “fit” of resource skills to project requirements, manages and balances scarce technical resources, forecasts and aids in planning for acquisition of resource shortfalls, and secures assignment of key resources to projects according to the project’s relative rank on the organization’s prioritized project list.

Resource Manager. In organizations with significant project activity, the responsibility for resource management may become a full-time job. One major insurance company titles this role the “Project Manager Role Steward.” Individual project managers, rather than having to “beg, borrow, and steal” resources wherever they can find them, turn to the resource manager for assistance. The RM prioritizes resource requests, manages the “fit” of resource skills to project requirements, manages and balances scarce technical resources, forecasts and aids in planning for acquisition of resource shortfalls, and secures assignment of key resources to projects according to the project’s relative rank on the organization’s prioritized project list.

![]() Organizational Development Analyst. Another project human-resource management role identified in some organizations, the ODA “floats” among projects identifying the human issues that often derail projects before they become a problem and working to resolve them. ODAs are a liaison between projects and the HR department.20

Organizational Development Analyst. Another project human-resource management role identified in some organizations, the ODA “floats” among projects identifying the human issues that often derail projects before they become a problem and working to resolve them. ODAs are a liaison between projects and the HR department.20

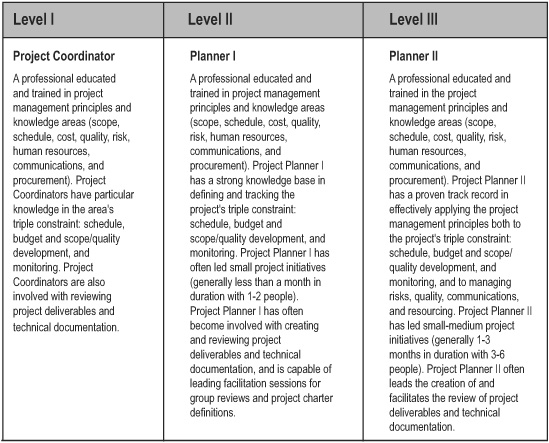

Table 17-1 outlines these positions and how one may be promoted to a higher division.

Competence-Building Activities

![]() Case Studies. One way to approximate the real-world application of professional skills is to create cases that highlight complex situations that demand skillful performance. Reading and studying such cases, the learner sees how to exercise judgment in applying any particular guideline or rule of thumb. As an organizational learning activity, project personnel can practice their problem-solving skills, either online or at lunch-hour learning sessions, by reviewing cases based on an actual organizational story or event.

Case Studies. One way to approximate the real-world application of professional skills is to create cases that highlight complex situations that demand skillful performance. Reading and studying such cases, the learner sees how to exercise judgment in applying any particular guideline or rule of thumb. As an organizational learning activity, project personnel can practice their problem-solving skills, either online or at lunch-hour learning sessions, by reviewing cases based on an actual organizational story or event.

![]() Mentoring and Coaching. Mentoring is a perfect match for project management development. For project managers, mentoring—whether we called it that or not—has always played an important role in professional development. As members of “the accidental profession,” project managers more often than not learned how to manage projects by managing projects and by observing other project managers in action. And mentoring still remains “the most effective way to bring new project managers up to speed quickly.”21

Mentoring and Coaching. Mentoring is a perfect match for project management development. For project managers, mentoring—whether we called it that or not—has always played an important role in professional development. As members of “the accidental profession,” project managers more often than not learned how to manage projects by managing projects and by observing other project managers in action. And mentoring still remains “the most effective way to bring new project managers up to speed quickly.”21

Frank Toney, PhD, of the Executive Initiative Institute, identifies mentoring as both a skill the project managers should master for success, and as one of the few reliable routes to competence in the project-based workplace. Lynn Crawford, of the University of Technology at Sydney (Australia), a leading project management thinker who was instrumental in developing Australia’s government-mandated competency measurement system for project managers, recommends mentoring and other social learning modes (such as communities of practice), as important learning tools for project management.22

Beyond mentoring, professional coaching combines self-focused personal value measurements, personality-type testing, and style-preference identification with feedback on personal and professional behaviors from a broad group of people. The professional coach is most likely educated in a behavioral field, such as psychology, and combines education and training with years of experience working with other clients to provide extremely valuable insight. Their counsel will help leverage strengths and eliminate behaviors that might derail success.23

Organizational Level |

|

Leadership Track |

|

Chief Project Officer |

Enterprise |

Strategic Project Office Director |

Enterprise |

Project Office Director |

Divisional/Departmental |

Portfolio Manager |

Enterprise |

Manager of Enterprise Project Managers |

Enterprise |

Manager, Project Managers |

Divisional/Departmental |

Global Program Manager |

Enterprise |

Enterprise Program Manager II |

Enterprise |

Enterprise Program Manager I |

Enterprise |

Enterprise Project Manager II |

Enterprise |

Enterprise Project Manger I |

Enterprise |

Program/Project Mentor I, II |

Enterprise or Divisional |

Program Manager II |

Divisional |

Program Manager I |

Divisional |

Project Manager III |

Divisional |

Project Manager II |

Divisional |

Project Manager I |

Divisional |

Technical Track |

|

Chief Project Officer |

Enterprise |

Strategic Project Office Director |

Enterprise |

Project Office Director |

Divisional |

Manager of Enterprise Project Support |

Enterprise |

Manager, Project Support |

Divisional/Departmental |

Enterprise Project Controller |

Enterprise |

Project Controller I |

Divisional |

Project Planner II |

Divisional |

Project Planner I |

Divisional/Departmental |

Project Estimator II |

Divisional |

Project Estimator I |

Divisional/Departmental |

Project Scheduler II |

Divisional |

Project Scheduler I |

Divisional/Departmental |

Specialty Positions |

|

Systems Analyst |

Any level |

Knowledge Management Coordinator |

Any level |

Methodologist |

Any level |

Technical Advisor |

Any level |

Budget Analyst |

Any level |

Business Analyst |

Any level |

Issues Management Coordinator |

Any level |

Change Control Coordinator |

Any level |

Risk Management Coordinator |

Any level |

Organizational Development Specialist |

Any level |

TABLE 17-1. PROGRAM/PROJECT MANAGER CAREER GROWTH POTENTIAL

![]() Personal Development Plans. Professional growth is also personal growth—a commitment to self-improvement. People who continuously seek feedback, work on their listening skills, polish communication skills, build relationships, and demonstrate control of their personal lives will rise above their peers. Yet many individuals passively accept (or grumble about) whatever growth programs are on offer by the organization.

Personal Development Plans. Professional growth is also personal growth—a commitment to self-improvement. People who continuously seek feedback, work on their listening skills, polish communication skills, build relationships, and demonstrate control of their personal lives will rise above their peers. Yet many individuals passively accept (or grumble about) whatever growth programs are on offer by the organization.

Instead, individuals should be encouraged to construct a personal development plan. The essence of this plan is to know yourself and the environment, build a road map to adapt and grow, and take personal ownership for change. Constructing a personal development plan requires openness to feedback, maturity to change behaviors, and willingness to practice new techniques.

Personal growth comes through self-evaluation and appraisal against personal standards, role models, group norms, peer behavior, and corporate or team culture. Input to the plan comes from both personal evaluation and relational sources, including supervisors, peers, clients, mentors, and friends. Reading is another critical resource for gaining new insights. Experiential education—conferences, seminars, and the like—is another important source for personal growth.24

Organizational Issues

Often in our discussion of competence, we focus narrowly on the personal traits and abilities of individuals. But even capable individuals still cannot work miracles within dysfunctional teams and organizations. That’s why culture change, not merely individual competence assessments, is required. “Organizational pathology,” says David Frame, is behavior rooted in an organizational culture that works against the best interest of the organization and its members. Organizations that punish the bearers of bad news are an example. Organizations that insist on applying outworn solutions to new problems similarly stifle personal competence in their members. The result? A “a profoundly unhappy workforce.”25

To develop the organization’s project management capability, says Christopher Sauer, it is desirable both to institutionalize the development of individual capabilities and to create learning that extends beyond the individual project manager’s skills and experience. He recommends the project office, as “a focal point in the organization,” where an environment conducive to the development and practice of project management capabilities can flourish.26

PROJECT MANAGEMENT CAREER PATHS

One thing that companies can do to support competence is to nurture the people who are responsible—to ensure that project managers have a clear and desirable career path that includes training, promotion criteria, recognition of achievement, and the opportunity to progress to the highest possible levels in the organization.27 Developing a career structure is essential to the development of an organization’s project management capability. The career path structure serves three purposes:

1. It allows the organization to match a project manager’s level of competence/experience to the difficulty and importance of a project.

2. It assures project managers that the investments they make in developing their professional skills will be rewarded.

3. It provides an incentive for people to stay with the company, because they can see a clear promotion path.28

Tables 17-2 and 17-3 show examples of career path structures for project management, on both the leadership (“art”) and technical sides (“science”).

The objectives of any career development program should be to improve skills, assess an employee’s readiness for advancement, define professional skill areas, create an equitable salary structure, create a positive and open environment for career discussion, ensure frequent feedback, and encourage a “change to grow” environment.

Project Controller: |

A Project Controller brings knowledge of and experience with implementing and using project controls to the team. Professionals in this category are hands-on experts in using project management software to plan and schedule tasks, manage interdependencies, roll-up and/or integrate plans and schedules, report status, and produce suggestions on how to make control process improvements. |

Project Team Leader: |

A professional, the Project Team Leader has a proven track record in effectively applying the project management principles to project performance, attainment of the triple constraint and high team performance/motivation. The Project Team Leader has led medium project initiatives (generally 6 months in duration) with up to 10 core team members. |

Project Manager: |

An experienced manager capable of successfully directing the planning, development and implementation of medium-large projects according to cost, schedule and scope requirements. The Project Manager participates in project initiation activities, including plan and budget preparation; leads the project management team in successfully executing the project as planned and budgeted throughout the project life cycle; and oversees the project closure activities including the collection of lessons learned. |

Program Manager: |

A recognized leader and manager well versed in the principles of project management, strategic and tactical planning, coordinating and integrating multiple large and complex projects into a comprehensive program. The Program Manager is capable of working with the client in defining their business drivers and defining how the program and project objectives meet the benefit triggers for business success. |

Senior Project Manager: |

A recognized leader and manager capable of successfully directing the planning, development and implementation of large and complex projects according to cost, schedule and scope requirements. The Senior Project Manager participates in all phases of the project (from concept to closure) and often has worked in a global environment or setting. |

Mentor: |

A project management professional with extensive project and program experience capable of working with project managers and project teams to help them put the processes, skills and support structure in place to effectively establish and manage projects. Typically, mentors provide consulting services to program managers, project managers, program/project teams and corporate managers. The Project Management Mentor is well versed in leading and managing program/project team members from diverse backgrounds, and within global and virtual settings. In program/project crisis the mentor can be called in to fill-in for an extended period of time for the senior project manager or program manager. |

TABLE 17-2. EXAMPLE CAREER PATH FOR A PROJECT MANAGER

TABLE 17-3. PROJECT COORDINATOR AND PROJECT PLANNER ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

A career path includes at least three elements in order to be valuable: experiential requirements, education/training requirements (knowledge acquisition), and documentation and tracking mechanisms.

![]() The experiential requirements detail the types of on-the-job activities that have to be accomplished for each level in the career path. Experiential opportunities need to be coordinated with the appropriate resource manager and the human resource department in the organization. A broad range of experiences are required for future project managers. It is not possible to develop them by restricting their experiences to one function. Thus, rather than climbing the ladder up the functional silo, project managers benefit from being exposed to a number of functions, perhaps moving back to functions they have fulfilled before, but in a more senior role. One writer has labeled this “the spiral staircase” career path.29

The experiential requirements detail the types of on-the-job activities that have to be accomplished for each level in the career path. Experiential opportunities need to be coordinated with the appropriate resource manager and the human resource department in the organization. A broad range of experiences are required for future project managers. It is not possible to develop them by restricting their experiences to one function. Thus, rather than climbing the ladder up the functional silo, project managers benefit from being exposed to a number of functions, perhaps moving back to functions they have fulfilled before, but in a more senior role. One writer has labeled this “the spiral staircase” career path.29

![]() The education and training requirements detail the types of knowledge that are required for each rung on the career ladder. At the lower levels, these tend to be basic courses designed to provide exposure and practice to the rudimentary skills required of that level. The upper level positions require more advanced strategic or tactical types of educational experiences. These may include topics that go beyond the realm of project management into business strategy, financial, or leadership opportunities. The educational program should be targeted to the requirements identified in the career path, and be designed in a progressive nature. In other words, the training requirements of team members are prerequisites for project managers and so on.30

The education and training requirements detail the types of knowledge that are required for each rung on the career ladder. At the lower levels, these tend to be basic courses designed to provide exposure and practice to the rudimentary skills required of that level. The upper level positions require more advanced strategic or tactical types of educational experiences. These may include topics that go beyond the realm of project management into business strategy, financial, or leadership opportunities. The educational program should be targeted to the requirements identified in the career path, and be designed in a progressive nature. In other words, the training requirements of team members are prerequisites for project managers and so on.30

![]() Documentation mechanisms include the attainment of certificates, degrees, or other credentials that substantiate the acquisition of the desired set of skills.

Documentation mechanisms include the attainment of certificates, degrees, or other credentials that substantiate the acquisition of the desired set of skills.

The first important criterion for project manager success is the desire to be a manager in general and a project manager in particular. Many organizations force people into the position even if they are not adept at it and do not desire to become one. The step from technical specialist to project manager may be the assumed progression when there is no way to move up a technical ladder. It is better, however, if alternative upward paths exist—one through technical managership and one through project leadership. With such dual promotional ladders, technical managers can stay in their departments and become core team members responsible for the technical portions of projects. Dual ladders also allow progression through project management, but project managers must be able to motivate technical specialists to do their best work.31

REFERENCES

1 The Standish Group, CHAOS Report, 1999; see also www.standishgroup.com and Johnson, James, Chaos: The dollar drain of IT project failures. Application Development Trends, January, 1995. Also, Gartner, Inc. reports that poor project manager competency accounts for 60% of project failures: see M. Light, T. Berg, “The Project Office: Teams, Processes and Tools,” Gartner Strategic Analysis Report, August 2000, also Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, Interview with Dr. Frank Toney, Project Management Best Practices Report, Aug. 2002; and the Robbins-Gioia study on project failure, 1999, posted at www.pmboulevard.com (accessed Sept. 1, 2004).

2 James S. Pennypacker and Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, eds. What Makes A Good Project Manager? Center for Business Practices, 2003.

3 Frank Toney. The Superior Project Manager, Marcel Dekker/Center for Business Practices, 2001.

4 James S. Pennypacker, The State of the PMO 2008-2007, Center for Business Practices, 2008.

5 Frame, J.D. The new project management: Corporate reengineering and other business realities. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1994.

6 Dennis Comninos and Anton Verwey, Business focused project management, Management Services, Jan. 2002; see also R. Graham and R. Englund R., Creating an Environment for Successful Projects, Jossey-Bass 1997; and J. Nicholas, Managing Business & Engineering Projects—Concepts and Implementation, Prentice Hall, 1990.

7 Tom Mochal, Is project management all administration? TechRepublic.com, posted 29 Nov. 2002. Accessed May 2004.

8 Christopher Sauer, LI Liu, Kim Johnston, Where project managers are kings, Project Management Journal, December, 2001.

9 David McClelland, The achieving society, Van Nostrand-Reinholdt, 1961.

10 Howard Risher, Aligning Pay and Results, Amacom, 1999.

11 Project Manager Competency Development Framework, PMI, 2002.

12 PM College can be accessed at www.pmcollege.com; Caliper at www.caliperonline.com.

13 The adoption of any new knowledge areas will be reflected in updates to the testing instruments.

14 Personal mastery is a concept discussed at length in the works of Stephen Covey, Peter Senge, and especially Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence, Bantam Books, 1995.

15 Jimmie West, Building Project Manager Competency, white paper, accessed at http://www.pmsolutions.com/articles/pm_competency.htm, January 15, 2005.10.

16 Jimmie West and Deborah Bigelow, Competency Assessment Programs, Chief Learning Officer, May 2003.

17 Building Project Manager Competency, White Paper, PM College, June 2004. Accessible at http://www.pmsolutions.com/articles/pm_skills.htm.

18 J. Kent Crawford, with Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin. Optimizing Human Capital with a Strategic ProjectOffice. Aurbach, 2005.

19 Jeanne Childers, personal interview, August 2003.

20 Agarwal, Ritu; Ferratt, Thomas W. Enduring practices for managing IT professionals. Communications of the ACM September 1, 2002.

21 Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, Mentoring: A Core Competency for Project Managers, People On Projects, June 2001.

22 Frank Toney, The Superior Project Manager, Marcel Dekker/CBP, 2001.

23 Mark Morgan, Career-building strategies: Are your skills helping you up the corporate ladder? Strategic Finance, June 1, 2002.

24 Ibid.

25 J. Davidson Frame, Building Project Management Competence, Jossey-Bass, 1999.

26 L.P Willcocks, D.E Feeny, & G. Islei (Eds.), Managing IT as a strategic resource. McGraw-Hill, 1999; and Christopher Sauer et al, ibid.

27 Jolyon Hallows, Information Systems Project Management, AMACOM, 1998.

28 Christopher Sauer, LI Liu, Kim Johnston, Where project managers are kings, Project Management Journal, December, 2001.

29 J. Rodney Turner, Anne Keegan, and Lynn Crawford, Learning by experience in the project-based organization, Proceedings of PMI Research Conference, PMI, 2000.

30 Freeman and Gould, The Art of Project Management: A Competency Model For Project Managers, white paper accessed June 2004 at www.BUTrain.com.

31 Robert J. Graham and Randall L. Englund, Creating an Environment for Successful Projects, Jossey-Bass, 1997.