CHAPTER 27

The Project Office: Rationale and Implementation

The value of sound project management has never been more in the public consciousness, thanks to studies by the Standish Group, the Gartner Group, and other IT research firms.1

But sound project management of individual projects is no longer enough. While there still are some instances in which a company is almost entirely focused on one or two major projects at a time—small software development firms or capital construction firms, for example—in most businesses dozens of projects exist throughout the company in various stages of completion (or, more commonly, of disarray). It wouldn’t be at all uncommon for a company to have several new product development projects in process, along with a process reengineering effort, a Six Sigma initiative, a new marketing program, and a fledgling e-business unit. Widen the scope of your thought to take in facilities, logistics, manufacturing, and public relations, and you begin to understand why most companies have no idea how many projects they have going at one time. And, when you consider that technology plays a role in almost all changes to organizations these days and that technology projects have an abysmal record of failure,2 it becomes apparent: unless all the projects that a company engages in are conceptualized, planned, executed, closed out, and archived in a systematic manner—that is, using the proven methodologies of project management—it will be impossible for an organization to keep track of which activities add value and which drain resources.

And the only way to have a global sense of how a company’s projects are doing is to have a project focus point: the Project Office.

No matter what name it carries—Center of Excellence, Project Support Office, Program Management Office, or Project Office—a home base for project managers and project management is a must for organizations to move from doing an adequate job of managing projects on an individual basis, to creating the organizational project management systems that adds value dependably and repeatedly.

WHY IMPLEMENT A PROJECT OFFICE?

Why do companies increasingly find they cannot do projects well enough without a Project Office? Imagine for a moment your organization without a finance department. Without documented procedures or systems, a shared vocabulary, or professional standards. Without systematic data collection or reporting. Without any knowledge transfer or management in the financial practice. Without a CFO or comptroller.

Whereas our imaginary company with no financial processes in place would at least have entry-level employees with four-year degrees in accounting or finance, project managers are often “accidental,” with no education in the specialty and no clear training plan for the future in mind. Even if a company has standardized on a project management tool across the enterprise, they may have access to the methodologies inherent in that tool, but it’s unlikely that everyone who works on project teams has had adequate training to make the best use of it. This is undoubtedly why the Gartner Group predicted in 2001 that companies that failed to establish a project office would experience twice as many major project delays, overruns, and cancellations as will companies with a PMO in place.3

Project management and, in particular, the project office are critical to the enterprise because most of the value-adding activities that companies do come in the form of projects. Think of operations as interest on capital already amassed; think of projects as the entrepreneurs who create new wealth. New products; new marketing initiatives; new facilities; new organizational processes implemented, mergers, and acquisitions: all of these are projects. Time is money—if a project is late for an amount of time equal to 10 percent of the projected life of the project, it loses about 30 percent of its potential profits.4

Furthermore, recent research is beginning to prove that a mature, strategic PMO provides performance benefits to the entire organization. In the 2007 study The State of the PMO, those organizations with mature, enterprise level PMOs that took a role in project resource management, project portfolio management, and organizational change management, scored consistently higher across eight measures of organizational performance, from customer satisfaction to financial outcomes.5

Ending Project Failure

In the past decade, there has been a trend toward improvement in our ability to pull off projects. Project slippage and failure rates are falling, at least in those application areas that attract research interest, such as software development and pharmaceutical R&D. Cost and time overruns are down. Large companies have made the most dramatic improvement. In 1994, the chance of a Fortune 500 company’s project coming in on time and on budget was 9 percent, its average cost $2.3 million. In 1998, that same project’s chances of success had risen to 24 percent, while the average project cost fell to $1.2 million.6

Three factors explain these encouraging results: 1) a trend toward smaller projects which are more successful because they are less complex; 2) better project management; and 3) greater use of “standard infrastructures,” such as those instituted through a Project Office. Large companies show up as more successful in the Standish Group study for one simple reason, in our view: large companies lead the pack in the establishment of enterprise-level project offices.7

The enterprise-level project office is so powerful because it helps to address the persistent management problems that plague projects:

![]() Poor tool implementation. Project managers who lack enterprise-wide multiproject planning, control, and tracking tools often find it impossible to comprehend the system as a whole.8 Such tools are rarely effectively implemented, trained for, or utilized except under the auspices of a project office. Buying a tool addresses the software issue; the “peopleware” issues must be addressed by a management entity that specializes in projects.

Poor tool implementation. Project managers who lack enterprise-wide multiproject planning, control, and tracking tools often find it impossible to comprehend the system as a whole.8 Such tools are rarely effectively implemented, trained for, or utilized except under the auspices of a project office. Buying a tool addresses the software issue; the “peopleware” issues must be addressed by a management entity that specializes in projects.

![]() Poor project management/managers. Most of the reasons technology projects fail are management-related rather than technical. Many enterprises have no processes in place to ensure that project managers are appropriately trained and evaluated.9 The average corporate HR department does not possess the knowledge to appropriately hire, train, supervise, and evaluate project management specialists, but an enterprise project office does.

Poor project management/managers. Most of the reasons technology projects fail are management-related rather than technical. Many enterprises have no processes in place to ensure that project managers are appropriately trained and evaluated.9 The average corporate HR department does not possess the knowledge to appropriately hire, train, supervise, and evaluate project management specialists, but an enterprise project office does.

![]() Lack of executive support for/understanding of projects. This correlates to project failure.10 An enterprise project office helps close the chasm between projects and executives. Those companies that have a senior-level executive who oversees the PMO reported greater project success rates (projects completed on time, on budget, and with all the original specifications) than those without.11

Lack of executive support for/understanding of projects. This correlates to project failure.10 An enterprise project office helps close the chasm between projects and executives. Those companies that have a senior-level executive who oversees the PMO reported greater project success rates (projects completed on time, on budget, and with all the original specifications) than those without.11

![]() Antiquated time-tracking processes. Accurate project resource tracking is imperative to successful project management. Project-based work requires new processes for reporting work progress and level of effort, but most companies’ time-tracking processes are owned by and originate in the HR department, and most HR departments are still using an employment model developed in the early Industrial Age.12

Antiquated time-tracking processes. Accurate project resource tracking is imperative to successful project management. Project-based work requires new processes for reporting work progress and level of effort, but most companies’ time-tracking processes are owned by and originate in the HR department, and most HR departments are still using an employment model developed in the early Industrial Age.12

![]() Lack of consistent methodology; lack of knowledge management. Enterprises that hold postimplementation reviews, harvest best practices and lessons learned, and identify reuse opportunities are laying the necessary groundwork for future successes.13 A Project Office shines as the repository for best practices in planning, estimating, risk assessment, scope containment, skills tracking, time and project reporting, maintaining and supporting methods and standards, and supporting the project manager.

Lack of consistent methodology; lack of knowledge management. Enterprises that hold postimplementation reviews, harvest best practices and lessons learned, and identify reuse opportunities are laying the necessary groundwork for future successes.13 A Project Office shines as the repository for best practices in planning, estimating, risk assessment, scope containment, skills tracking, time and project reporting, maintaining and supporting methods and standards, and supporting the project manager.

Adding Corporate Benefits

Project portfolio management. If an enterprise-level project management office does not own the process of project inventory, prioritization, and selection, it cannot be done well. The META Group recommends this strategy, and those companies that have put enterprise-wide PPM in place, such as Cabelas and Northwestern Mutual Life, have relied on it. In fact, while intra-departmental portfolios may perhaps be selected and balanced without involvement of a project management office, it’s doubtful that anything on a wider scale can succeed … and you can’t optimize the system by balancing only parts of it.14

You can’t manage what you can’t measure, the old saying goes, and unless all the projects on the table can be held up to the light and compared to each other, a company has no way of managing them strategically, no way of making intelligent resource allocation decisions, and no way of knowing what to delete and what to add. And the only way to have a global sense of how a company’s projects are doing is to have some sort of project focus point.15

Problems resolved by project offices. These include projects not supported by senior executives, lack of authority, conflict over project ownership, difficulty of cross functional interface with projects, project prioritization and selection, development of project manager and project team capabilities, and knowledge management issues.16

THE CHALLENGES OF IMPLEMENTING A PMO

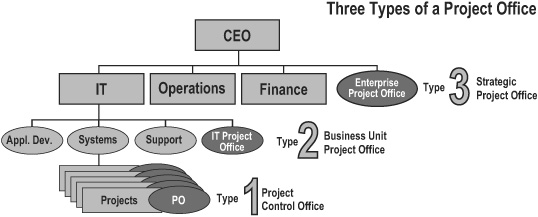

Many hold the misconception that a PMO is merely a project controls office that focuses on scheduling and reports. At one time, of course, this was true: in the old matrix organization, if a project was lucky to have a “project office,” it was usually nothing more than a “war room” with some Gantt charts on the walls and perhaps a scheduler or two. This simple single-project control office is what we’ll call a Type 1 Project Office (see Figure 27-1).

FIGURE 27-1. THREE TYPES OF A PROJECT OFFICE

Inside the matrix. When project management’s early tools—Gantt charts, network diagrams, and PERT—began to be used in private industry, the new project managers faced a hurdle: business was also fashioned on the command-and-control model. Putting together an interdisciplinary team was a process fraught with bureaucratic roadblocks. The earliest uses of project management—in capital construction, civil engineering, and R&D—imposed the idea of the project schedule, project objectives, and project team on an existing organizational structure that was very rigid. Without a departmental home or a functional silo of its own, a project was the organizational stepchild—even though it may have been, in terms of dollars or prestige, the most important thing going on. Thus was born the concept of the “matrix organization”—a stopgap way of defining how projects were supposed to get done within an organizational structure unsuitable to project work. It was a “patch,” to use a software development term—not a new version of the organization.

Up the steps to maturity. A Type 2, or “divisional-level,” Project Office may still provide support for individual projects, but its primary challenge is to integrate multiple projects of varying sizes within a division from small, short-term initiatives to multi-month or multi-year initiatives that require dozens of resources and complex integration of technologies. With a Type 2 PMO, an organization can, for the first time, integrate resources effectively, at least over a set of related projects. We should note that while the Type 2 PMO is most often an IT office, organizing around projects is not “an IT thing.” Project offices have arisen first in IT because of the competitive pressure to make IT projects work. IT is one of our primary drivers of economic prosperity; America spends over $200 billion annually on software development projects—many of which fail. That IT project offices have been proven to reduce waste, bring projects in on time, and improve morale should be a wake-up call for all areas of the corporation, and in all industries.17

For an organization without any repeatable processes in place, which are at the first, or Initial level on a Project Management Maturity Model,18 these levels of Project Office organization are beneficial. At the individual project level, applying the discipline of project management creates significant value to the project because it begins to define basic processes that can later be applied to other projects within the organization. At Type 2 and higher, the project office not only focuses on project success, but also migrates processes to other projects and divisions, thus providing a much higher level of efficiency in managing resources across projects. A Type 2 project office allows an organization to determine when resource shortages exist and to have enough information at their fingertips to make decisions on whether to hire or contract additional resources. And at Type 3, the enterprise project office applies processes, resource management, prioritization, and systems thinking across the entire organization.19, 20

Advantages of the Enterprise-Level, or Strategic, Project Management Office

Although many companies today still struggle to implement even Type 2 project offices, our primary focus is on the Type 3 project office, which we call the Strategic Project Office (SPO). Why? Because that’s where organizations can derive the most benefit. Like the matrix organization, lower-level project offices are a way station: a stage between the old-style organization and the new, project-based enterprise.

At the corporate level, the project office serves as a repository for the standards, processes, and methodologies that improve individual project performance in all divisions. It also serves to mitigate conflicts in the competition for resources, and to identify areas where there may be common resources that could be used across the enterprise. More important, a corporate project office allows the organization to manage its entire collection of projects as one or more interrelated portfolios. Executive management can get the big picture of all project activity across the enterprise from a central source (the Project Office), project priority can be judged according to a standard set of criteria, and projects can at last fulfill their promise as agents of enterprise strategy. The higher the Project Office resides in the organization, the fewer the problems reported. A project office is a communication tool, maintaining a consistent flow of communication to senior executives and report both successes and problem areas.21

The Gartner Group has identified several key roles for a Project Office,22 all of which are most effectively carried out at Type 3:

![]() Developer, documenter, and repository of a standard methodology (a consistent set of tools and processes for projects). The SPO provides a common language and set of practices. This methodology boosts productivity and individual capability and takes a great deal of the frustration out of project work. Research by the Center for Business Practices revealed that over 68 percent of companies who implemented basic methodology experienced increased productivity, and 37 percent reported improvement in employee satisfaction.23

Developer, documenter, and repository of a standard methodology (a consistent set of tools and processes for projects). The SPO provides a common language and set of practices. This methodology boosts productivity and individual capability and takes a great deal of the frustration out of project work. Research by the Center for Business Practices revealed that over 68 percent of companies who implemented basic methodology experienced increased productivity, and 37 percent reported improvement in employee satisfaction.23

![]() Center for the collection of data about project human resources. Based on experience from previous projects, the SPO can validate business assumptions about projects as to people, costs, and time; it is also a source of information on cross-functional project resource conflicts or synergies.

Center for the collection of data about project human resources. Based on experience from previous projects, the SPO can validate business assumptions about projects as to people, costs, and time; it is also a source of information on cross-functional project resource conflicts or synergies.

As a project management consulting center, the SPO provides a seat of governing responsibility for project management and acts as a consultant and mentor to the entire organization, staffing projects with project managers or deploying them as consultants or mentors. As a center for the development of expertise, the SPO makes possible a systematic, integrated professional development path and ties training to real project needs as well as rewarding project teams in ways that reflect and reinforce success on projects. This is quite different from the reward and training systems presently in place in most organizations, which tend to focus on functional areas and ignore project work in evaluation, training, and rewards.

As a knowledge management center for project management, the SPO provides a locus not only for project management knowledge, but for knowledge about the content of the organization’s projects. With a “library” of business cases, plans, budgets, schedules, reports, lessons learned, and histories, as well as a formal and informal network of people who have worked on a variety of projects, the SPO is a knowledge management center that maximizes and creates new intellectual capital. Knowledge is best created and transferred in a social network or community, and the SPO provides just that. Through mentoring, both within the SPO among project managers and across the enterprise to people in all specialty areas, knowledge transfer about how to get things done on deadline and within budget is facilitated.24

The enterprise-level project office facilitates the management of projects on one level, and improves management of the entire enterprise via project portfolio management and linking projects to corporate strategy on another level. More than establishing an office and creating reports, it infuses cultural change throughout the organization.

Table 27-1 shows the capabilities and features of each type of PMO.

![]() A systems-thinking perspective. To effectively deploy project management throughout an organization, all the players must be on board. Everyone from the project team member on up to the executive sponsors of projects must understand what is happening with project management. This translates to an organizational setting in which virtually everyone who is touched by a project is impacted by what happens with the project management initiative. Ultimately this impact sweeps across the entire corporation. That’s why effective organizations have project offices located at the corporate level, providing data on total corporate funding for projects, the resources utilized across all corporate projects, capital requirements for projects at the corporate level, materials impact, supplies impact, and the procurement chain impacts. A fully mature organization may actually have project offices at each of the levels described in Figure 27-1: a Strategic Project Office at the corporate level to deal with enterprise (cross-divisional) programs/projects, corporate reporting, corporate portfolio management, etc.; and a divisional Project Office to deal with divisional programs/projects, divisional resource management, divisional portfolios, and the division’s contribution (technology, labor, etc.) to corporate programs/projects. And, there may be one or more Type 1 Project Offices within a divisional PMO dealing with major projects.

A systems-thinking perspective. To effectively deploy project management throughout an organization, all the players must be on board. Everyone from the project team member on up to the executive sponsors of projects must understand what is happening with project management. This translates to an organizational setting in which virtually everyone who is touched by a project is impacted by what happens with the project management initiative. Ultimately this impact sweeps across the entire corporation. That’s why effective organizations have project offices located at the corporate level, providing data on total corporate funding for projects, the resources utilized across all corporate projects, capital requirements for projects at the corporate level, materials impact, supplies impact, and the procurement chain impacts. A fully mature organization may actually have project offices at each of the levels described in Figure 27-1: a Strategic Project Office at the corporate level to deal with enterprise (cross-divisional) programs/projects, corporate reporting, corporate portfolio management, etc.; and a divisional Project Office to deal with divisional programs/projects, divisional resource management, divisional portfolios, and the division’s contribution (technology, labor, etc.) to corporate programs/projects. And, there may be one or more Type 1 Project Offices within a divisional PMO dealing with major projects.

TABLE 27-1. CAPABILITIES OF VARIOUS TYPES OF PROJECT OFFICE

![]() Knowledge management. A whole new set of procedures and standards need to be established along with a common mechanism for storing and sharing that information. Along with this goes the training process and data collection routine that must be established to get information into this database before knowledge transfer can take place.

Knowledge management. A whole new set of procedures and standards need to be established along with a common mechanism for storing and sharing that information. Along with this goes the training process and data collection routine that must be established to get information into this database before knowledge transfer can take place.

Project/program managers will make good decisions with good data. Without good data, decisions are going to be very poor. So the organization is faced with a very complex integrated system and process that they have very little knowledge how to deploy. That’s why the Gartner Group recommends incorporating a contractor or consultant in the implementation strategy. It’s necessary to get folks in who have actually done systems deployment in the past so that the probability of success is going to be much higher.

The Objective: Results and Fast

All this costs money, so at the end of the day, it is absolutely essential that an organization is able to quantify the value that project management brings.

How can the initiative show results fast enough to avoid top management loss of interest? Dianne Bridges, PMP, writes that there are two ways to demonstrate the immediate value of the Project Office: through short-term initiatives and project mentoring.25 Short-term initiatives provide solutions to immediate concerns and take care of issues surfaced by key stakeholders. These are items that can be implemented quickly, while at the same time they take care of organizational top-priority concerns. Examples include: support for new projects and projects in need; an inventory of projects (new product development, information technology, business enhancements, etc.); summary reports and metrics; informal training lunches; project planning or project control workshops; templates, project audits, and identification of project managers or those who aspire to the role.

In conjunction with the short-term initiatives, project mentoring is an excellent way to provide immediate project management value to projects that are in the initial start-up phase or are in need of support, without waiting for the implementation of formal training programs, or process roll-outs.

The best approach to building organizational and individual maturity is to move forward quickly—show results on specific projects within six months, really begin changing the culture within the first year, and begin showing corporate results within a two-year time frame. But be prepared—this is no quick fix. It will take anywhere up to five years to fully deploy a Strategic Project Office.26

What does success look like? How will you know when you have arrived? Research studies allow us to paint a picture of the organization that has demonstrated competence in managing projects, and managing by projects:

• Top management understands project management basics.

• Effective training programs are in place.

• Clear project management systems and processes have been established.

• There is improved coordination of inter-group activities.

• There is an enhanced goal focus on the part of employees.

• Redundant or duplicate functions are eliminated.

• Project expertise is centralized.

• Changes in organizational culture including new information systems, altered communications channels, and new performance measurement strategies.27, 28

PMO in Place? Don’t Relax Yet

A trend that first surfaced in 2002 at the Project Management Benchmarking Forums, and which has continued to plague PMOs despite increasing organizational clout, visibility and proven value-add, was of companies that had achieved a mature project management process under the auspices of an enterprise project office, but which were disinvesting in project management in the name of cost-cutting exercises.

Forum participants—representatives of project management practices within some of America’s top corporations—described the expressed opinions of their executive leadership as paradoxical: on one hand they claimed to support and value project management; on the other hand they were slashing project management office budgets and cutting training for project managers. In a tight economy, management identified the entire project management exercise as an overhead expense.

Ironically, the most successful and long-standing project management offices may be the most vulnerable to cost cutting because the organization takes good project management for granted. An article in Computing Canada by HMS Software president Chris Vandersluis characterized the attitude as: “Can’t we just do all of this in Excel like we used to?” and “The projects aren’t a problem; why do we spend so much money on managing them?”29

Once implemented, good project management becomes invisible and, paradoxically, that can be a problem. The effects of good change management, good planning, resource capacity planning, and variance management mean that projects just seem to run themselves. Management forgets that the costs associated with maintaining a project management structure are outstripped by the potential costs of having no project management structure. Vandersluis describes the PM-free environment as “projects that run late and over budget … a mismatch of resources to projects … clients [and] suppliers are unhappy … shareholders are unhappy …,” and boldly states that “losing the efficiency that comes with a corporate-wide project management environment can take a company from barely profitable to completely unprofitable in a short period of time.”30

Project Office directors and managers often wonder out loud why processes like accounting are accepted as costs of doing business, while the project management process constantly struggles for survival on the organizational edge. The constant effort to make visible to management costs they didn’t incur saps energy that would be better spent on managing projects. But this vigilance is simply part of the requirements for maintaining your Project Office, once established, as a visible and appreciated part of organizational life.

REFERENCES

1 The Standish Group, 2000 CHAOS Report. See www.standishgroup.com.; also M. Light and T. Berg, Gartner Strategic Analysis Report: The Project Office: Teams, Processes and Tools, 01 August 2000.

2 Ibid.

3 Light and Berg, Gartner Strategic Analysis Report.

4 Preston Smith and Donald Reinertsen, Developing Products in Half the Time, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991.

5 James S. Pennypacker, The State of the PMO, 2007–2008. Center for Business Practices, 2008.

6 Standish Group, Report.

7 Value of Project Management Study, Center for Business Practices, 2001.

8 Lauren Gibbons Paul, “Turning failure into success: Maintain momentum,” Network World, 22 Nov. 1999.

9 Ibid.

10 J. Roberts, J. Furlonger, “Successful IS Project Management,” Gartner Group, 18 April 2000.

11 Lorraine Cosgrove Ware, By the Numbers, CIO Magazine, July 1, 2003

12 C. Natale, “IT Project Management: Do Not Lose Track of Time,” Gartner Group, 9 May 2000.

13 Bailey, Richard W., II, “Six Steps to Project Recovery,” PM Network, May 2000.

14 Project Portfolio Management: A Benchmark of Current Business Practices, CBP Research, 2003.

15 J. Kent Crawford, Portfolio Management: Overview and best practices, Project Management for Business Professionals, Joan Knutson, ed., Wiley, 2001.

16 Comninos and Verwey, ibid.

17 C. W. Ibbs and Young-Hoon Kwak, Benchmarking Project Management Organizations, PM Network, Feb. 1998: 49–53.

18 A capability maturity model is an organizational assessment tool that helps companies identify process maturity—or lack thereof—by documenting how various processes are actually carried out against a standard of best practice behaviors for that process. While there are several versions of maturity model in circulation for project management, we used one developed by our company as the basis for the assessment described in Table 24-1. This model is described in Project Management Maturity Model, by J. Kent Crawford, Marcel Dekker, 2001.

19 J. Kent Crawford, Project Management Maturity Model, Marcel Dekker, 2001.

20 Software Engineering Institute, “Capability Maturity Model for Software Development,” www.cmu.edu/sei.

21 Ware, “By the Numbers.”

22 Light and Berg, Gartner Strategic Analysis Report.

23 Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, The Value of Project Management, PM Best Practices Report, Oct. 2000.

24 J. Kent Crawford, The Strategic Project Office, Marcel Dekker, 2001. (Second edition forthcoming from Auerbach Books, 2010.)

25 Dianne Bridges and Kent Crawford, “How to Start Up and Roll Out a Project Office,” Proceedings of the PMI Annual Seminars and Symposium, PMI, 2000.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibbs and Kwak, Benchmarking Project Management Organizations.

28. J. Davidson Frame, “Understanding the New Project Management,” Aug 7 1996 Presentation to Project World, Washington, DC.

29 Chris Vandersluis, Cutting project office is detrimental to corporate health, Computing Canada, Sept. 2002.

30 Jeannette Cabanis-Brewin, Penny Wise, Pound Foolish: Cost-cutting in the project office, Best Practices e-Advisor, Center for Business Practices, Jun. 2004.