Chapter 13

Managing Successful Collaboration Communities

In This Chapter

![]() Keeping a social community healthy

Keeping a social community healthy

![]() Forming a community management team

Forming a community management team

![]() Focusing collaboration in groups and project workspaces

Focusing collaboration in groups and project workspaces

Online collaboration becomes social only when you add community, which extends the scale of interaction between one project or one team, making it more widespread and ongoing. You can assign project team members to check into a collaboration workspace, and they will comply if their job depends on it. People come back to a community of their own accord because they find it valuable and want to be part of something larger.

Community isn’t really a matter of technology. Tools can make a difference by providing an environment for communities to form and sustain themselves, but what matters a lot more is how those tools are used and how effectively communities are managed. In this chapter, I help you understand how you can manage a successful, healthy social collaboration community. When social collaboration fails, it most often fails because communities fail to form in the first place or because they fall into disuse and disorder.

Healthy collaboration communities have the right combination of spontaneous, free-form participation and enough organization to make it easy for members to find both content and people who are relevant to their interests and their work.

Keeping a Social Community Healthy

As a community manager, you know that productive collaboration communities don’t just happen, spontaneously, with the activation of a software tool. Even those collaboration communities that get off to a great start don’t remain healthy without proper care and feeding. Communities are subject to entropy, the tendency of the universe to devolve into disorder. What you’re trying to avoid is the collaboration network that, in theory, seemed so promising as a way of organizing work and putting information in context becomes a rat’s nest of overlapping discussion and project groups, duplicate versions of documents, and activities that waste time rather than making everyone more productive.

Avoiding these traps requires active community management and system administration. At the same time, the role of community management has to be one of coaching and nurturing communities. Communities do not form by management edict, or in response to a memo.

“You can’t force community,” writes Deborah Ng in Community Management For Dummies. “You can’t put members in the same virtual room and expect magic to happen. Instead, you have to get the party started and keep it going.” If you read her book (which I would recommend even if we didn’t share a publisher), you will learn a lot about how communities form and function. However, her book is primarily focused on externally accessible online communities, such as the customer support communities many firms operate so their customers can share tips and answer each other’s questions. In this section, I tell you what you can learn from those external communities, and I give you some guidelines for how you can keep an internal community healthy and productive.

Much of the material that follows on the types of people you encounter in an online community is adapted from Community Management For Dummies, with my own tweaks to make it more relevant to the work environment.

Learning from external communities

For the sake of maintaining focus within a broad subject area, this book primarily focuses on internal collaboration networks limited to employees and perhaps trusted freelancers and contractors. In Chapter 14, I cover scenarios where it makes sense to include selected external users, such as partners or customers, in a subcommunity within your collaboration network. This can be a useful way of engaging in projects that stretch beyond the bounds of your organization without giving those people access to internal strategic discussions.

Managing public social communities — such as those communities that companies provide for customer service and peer-to-peer sharing of tips among their customers — is a different kind of challenge and mostly outside the scope of this book. However, there are good reasons for internal community managers to study the dynamics of truly public social communities here.

![]() Participation is voluntary. The users of a public social community participate because they find the community interesting and useful. The community manager has no leverage to compel participation.

Participation is voluntary. The users of a public social community participate because they find the community interesting and useful. The community manager has no leverage to compel participation.

An internal corporate social network manager actually can compel a certain degree of usage — for example, by making essential employee information available only on the collaboration network. Still, active (rather than grudging) participation remains within the control of the individual, who will actively participate only if the community is interesting and useful.

![]() Public communities are an open book. Getting a peek at another organization’s internal collaboration network can be challenging. If you want to see a lot of community managers at work, study public examples, such as:

Public communities are an open book. Getting a peek at another organization’s internal collaboration network can be challenging. If you want to see a lot of community managers at work, study public examples, such as:

• Home Depot (http://community.homedepot.com)

• SAP Community Network (http://scn.sap.com)

• Jive Community (http://community.jivesoftware.com)

• IBM DeveloperWorks (www.ibm.com/developerworks)

![]() Public communities set expectations for private ones. Watch public communities at work for clues to patterns (good and bad) that will also play out within your collaboration network.

Public communities set expectations for private ones. Watch public communities at work for clues to patterns (good and bad) that will also play out within your collaboration network.

Analyzing the community population

One of the roles of any community manager is to jump in as moderator, when necessary, deleting posts that are profane, offensive, or otherwise in violation of community rules. They must also deal with what are known in the trade as trolls: namely, those people who are aggressively provocative and disruptive, sucking energy out of the community rather than putting energy into it.

What are the common elements of all communities, public or private? First, consider motivation. People voluntarily share in an online community for a few reasons:

![]() They want to belong. We are social animals and want to feel part of something larger. Sometimes the co-workers we have the most natural affiliation with are not sitting in the same office (or, in the age of telecommuting, we may be alone in the office).

They want to belong. We are social animals and want to feel part of something larger. Sometimes the co-workers we have the most natural affiliation with are not sitting in the same office (or, in the age of telecommuting, we may be alone in the office).

![]() They know things that other people don’t. They want to give answers, enlighten, and maybe show off a little.

They know things that other people don’t. They want to give answers, enlighten, and maybe show off a little.

![]() They are returning the favor. The community has been helpful to them, and they want to pay it back.

They are returning the favor. The community has been helpful to them, and they want to pay it back.

![]() They have tips or shortcuts to share. They have found a better way to do something at work and hate to see others wasting time doing it the hard way.

They have tips or shortcuts to share. They have found a better way to do something at work and hate to see others wasting time doing it the hard way.

![]() They enjoy recognition. When they share something useful, and other people click “Like,” they feel good and know they are getting noticed.

They enjoy recognition. When they share something useful, and other people click “Like,” they feel good and know they are getting noticed.

![]() They are scoring points. By giving to the community, they are banking good will, which will make it easier for them to ask for help in the future.

They are scoring points. By giving to the community, they are banking good will, which will make it easier for them to ask for help in the future.

![]() They are establishing trust and credibility. By dispensing a steady stream of useful tips and pointers, they know they are building credibility that will pay off when they have an important message to spread.

They are establishing trust and credibility. By dispensing a steady stream of useful tips and pointers, they know they are building credibility that will pay off when they have an important message to spread.

People will share information others may find useful out of the purest generosity, but they may also want to show how smart they are or burnish their professional brands. They want to build trust and credibility within the organization so they will have more influence and be able to get trust when they need it. They are looking to make connections that may pay off later in a promotion, a transfer, or a recommendation for a new job.

Not everyone participates at the same level. Here are a few of the common types you will encounter. The labels have been adapted from Online Community Management For Dummies, but the descriptions are mine.

![]() The Lurker: You rarely hear from lurkers. They are there in the background, watching, reading, and consuming content but rarely contributing. As I discuss later, community managers should appreciate passive participation over non-participation. If the lurker finds value in the community, even without actively contributing, that is a good thing. Still, a community that consisted only of lurkers would not work.

The Lurker: You rarely hear from lurkers. They are there in the background, watching, reading, and consuming content but rarely contributing. As I discuss later, community managers should appreciate passive participation over non-participation. If the lurker finds value in the community, even without actively contributing, that is a good thing. Still, a community that consisted only of lurkers would not work.

![]() The Newbie: Newbies are new members of the community. They may be new employees or employees who only recently created an account. They are still figuring out the software and may not understand the ground rules. Their level of participation ranges from tentative to over-eager. They need help from the community manager and the community at large finding their bearings and becoming long-term productive members.

The Newbie: Newbies are new members of the community. They may be new employees or employees who only recently created an account. They are still figuring out the software and may not understand the ground rules. Their level of participation ranges from tentative to over-eager. They need help from the community manager and the community at large finding their bearings and becoming long-term productive members.

![]() The Regular: Everyone knows The Regular as a familiar face in the online community. The Regular may win credibility as a known quantity, just by being so active. If nothing else, The Regular knows how to navigate the online community and can help guide others through it.

The Regular: Everyone knows The Regular as a familiar face in the online community. The Regular may win credibility as a known quantity, just by being so active. If nothing else, The Regular knows how to navigate the online community and can help guide others through it.

![]() The Leader: The Leader is a knowledgeable, established community member who is either self-appointed or appointed by the community into a leadership role. When The Leader speaks up, people listen.

The Leader: The Leader is a knowledgeable, established community member who is either self-appointed or appointed by the community into a leadership role. When The Leader speaks up, people listen.

The Leader may also hold some ranking position offline within the organization. Not always, though. Sometimes the online community provides employees with an opportunity to demonstrate leadership skills they have not displayed in other contexts — in which case, their online leadership may translate into greater offline success.

![]() The Expert: The Expert knows everything about everything — or claims to. You want people with legitimate expertise to participate in the community but will also have to contend with some know-it-alls.

The Expert: The Expert knows everything about everything — or claims to. You want people with legitimate expertise to participate in the community but will also have to contend with some know-it-alls.

Should you try to coax people toward higher levels of participation? Absolutely. Yet given that part of the point of social collaboration is to create a richer knowledge resource for the community, shouldn’t you appreciate when people take advantage of that resource? One person who made this point to me is Tracy Maurer, a community manager and strategist at UBM, the publisher of InformationWeek and organizer of events including the E2 Conference series. The negative view of lurkers “where the idea was all they do is come in and watch — they don’t contribute anything — I wouldn’t say that’s a fair assessment,” she says. Throughout our lives, we learn new skills by observing how others do them before we try them ourselves, she points out. In other words, there is wisdom in listening and learning before you speak up. Part of the value of a social collaboration platform is to make it easier to publish information, she says, “and if you don’t have readers, what the heck good is it?”

There are also some negative personality types to watch for:

![]() The Malcontent: Complains about everything from the collaboration platform to management and never has anything positive to say.

The Malcontent: Complains about everything from the collaboration platform to management and never has anything positive to say.

![]() The Heckler: Questions or comments sarcastically about everything, not so much to disagree as to show her own superiority or to make others look bad.

The Heckler: Questions or comments sarcastically about everything, not so much to disagree as to show her own superiority or to make others look bad.

![]() The Rabble Rouser: Determined to incite the community to riot, rather than discuss disagreements in a respectful manner.

The Rabble Rouser: Determined to incite the community to riot, rather than discuss disagreements in a respectful manner.

![]() The Troll: The anonymity of the Internet gives the troll the keyboard courage to be cruel to other members.

The Troll: The anonymity of the Internet gives the troll the keyboard courage to be cruel to other members.

Compared with anonymous public social forums, the worst of these patterns are much rarer in a social collaboration network where obnoxious behavior or disrespectful talk about management can be a career-ending move. There may be some heckling and some rabble rousing going on, but it will have to be couched in the form of sarcasm or passive aggressive behavior to sneak under the radar.

Here are some suggestions for dealing with negativity on the social collaboration system:

![]() Steer colleagues toward more positive expression. Even cloaked, negative sentiment about the company and its goals tends to reflect poorly on the person expressing it. If you help the malcontents and hecklers understand how they are making themselves look, that may be enough to make them stop. Or, if there are legitimate concerns mixed in with their complaints, you can try to redirect them toward constructive criticism that seeks solutions. Worth a try.

Steer colleagues toward more positive expression. Even cloaked, negative sentiment about the company and its goals tends to reflect poorly on the person expressing it. If you help the malcontents and hecklers understand how they are making themselves look, that may be enough to make them stop. Or, if there are legitimate concerns mixed in with their complaints, you can try to redirect them toward constructive criticism that seeks solutions. Worth a try.

![]() Acknowledge complaints and do your best to resolve the issues or offer workarounds. Will you have some malcontents and hecklers where the collaboration environment itself is concerned? Count on it. You should be prepared for their complaints about what the platform can’t do or doesn’t do the way they would expect it to. You may never win them over, but do the best you can to prevent them from putting so much focus on the platform’s shortcomings that they distract other community members from discovering its practical uses.

Acknowledge complaints and do your best to resolve the issues or offer workarounds. Will you have some malcontents and hecklers where the collaboration environment itself is concerned? Count on it. You should be prepared for their complaints about what the platform can’t do or doesn’t do the way they would expect it to. You may never win them over, but do the best you can to prevent them from putting so much focus on the platform’s shortcomings that they distract other community members from discovering its practical uses.

If you can, address their legitimate complaints or feature requests with the vendor or by reconfiguring the collaboration network. Just understand that a habitual malcontent will not be satisfied no matter what you change.

If you can, address their legitimate complaints or feature requests with the vendor or by reconfiguring the collaboration network. Just understand that a habitual malcontent will not be satisfied no matter what you change.

Models of social community quality

The Community Maturity Model shown in Figure 13-1 was developed by Rachel Happe and Jim Storer, the co-founders of The Community Roundtable (CR), an organization devoted to research and gathering best practices about community management and strategy.

Turning social community management from a casual effort to an organizational discipline that spans many teams and groups “is actually pretty difficult and disruptive because it requires cultural, leadership, strategy, workflow, and operational changes,” Happe writes in a blog post on the model. “However, it is critical if organizations don’t want to have their social efforts isolated from everything else, which doesn’t work very well anyway.” Her idea for avoiding this disruption was to develop a common framework and taxonomy for the elements of successful social communities, providing a common vocabulary for strategy discussions as well as training and certification.

The competencies laid out in the model are

1. Strategy

2. Leadership

3. Culture

4. Community Management

5. Content & Programming

6. Policy & Governance

7. Tools

8. Measurement

Figure 13-1: The Community Maturity Model.

At each stage of development (Hierarchy, Emergent Community, Community, and Network), the organization graduates to a more mature stage of each of these competencies. While the stages will play out a little differently in every organization, the Community Maturity Model attempts to show the patterns and connections among these competencies. For example, a truly integrated strategy is interdependent with achieving distributed leadership that spans multiple communities, integrated roles and processes for community management, and an integrated suite of social collaboration tools. Trying to implement a truly integrated strategy with a hodgepodge of consumer-grade tools would not really work, nor would the best most integrated tool suite make up for a reactive, command-and-control culture where community members are reluctant to participate because they don’t know whether they will be rewarded or punished.

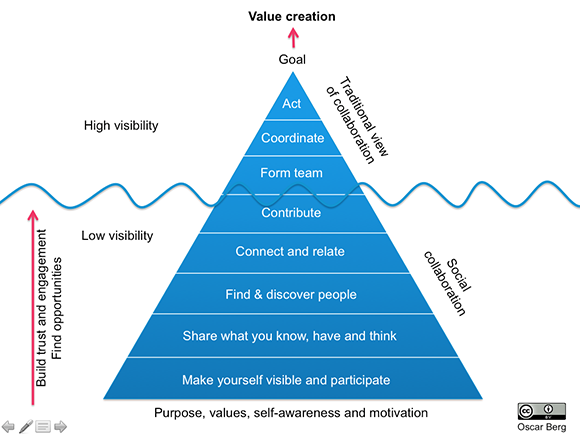

The digital strategist Oscar Berg pictures the relationship between social and collaboration activities as a pyramid (shown in Figure 13-2), where the broad base of more community-oriented social collaboration provides the foundation for more intensive team collaboration around specific projects and work processes.

Courtesy of Oscar Berg

Figure 13-2: Oscar Berg’s collaboration pyramid (or iceberg).

"The majority of the value-creation activities in an enterprise are hidden. They happen below the surface," Berg writes in his blog at www.thecontenteconomy.com. "What we see when we think of collaboration in the traditional sense (structured team-based collaboration) is the tip of the iceberg — teams who are coordinating their actions to achieve some goal. We don't see — and thus don't recognize — all the activities which have enabled the team to form and which help them throughout their journey."

In other words, if you really want employees to collaborate effectively to create and deliver new products, you need to pay equal attention to the social community underpinnings as to the more formal team collaboration and project management. Berg exalts the value of “ongoing community building that makes people trust each other and commit themselves to a shared purpose.”

These models provide inspiration for what an organization can aim to achieve with social collaboration. Now, how are you going to make it happen?

Moderating conversations

Responsibility for moderating online community content and conversations is typically divided among platform administrators, community managers, and the owners of specific groups or collaboration spaces. Moderation is considered a system administration task, and a person with moderation rights has the power to edit, reclassify, or delete content that others have posted. That is primarily what I’m talking about here although you can also think in terms of the role the moderator of a panel discussion plays, which is more about keeping the conversation going.

Some of the things you want to be able to delete are

![]() Profane, vulgar, or pornographic posts or images

Profane, vulgar, or pornographic posts or images

![]() Personal attacks on other community members

Personal attacks on other community members

![]() Sensitive private or confidential information shared too widely or in a space with inadequate security controls

Sensitive private or confidential information shared too widely or in a space with inadequate security controls

![]() Inaccurate content about company leaders, policies, or procedures (may be better to correct than delete)

Inaccurate content about company leaders, policies, or procedures (may be better to correct than delete)

The power to delete inappropriate content is important and necessary, but preventing it from being posted in the first place is far better.

When it does come up, the decision to delete content deserves careful thought. There are extreme cases where it is obviously the right decision. Examples would include pornography or other blatantly offensive content, as well as confidential information posted in a public space.

Instead, a more appropriate response would be to intervene by

![]() Reminding participants of the company’s acceptable use policies, which you will have designed to discourage this kind of loose talk

Reminding participants of the company’s acceptable use policies, which you will have designed to discourage this kind of loose talk

![]() Posting a factual rebuttal of the misinformation being disseminated

Posting a factual rebuttal of the misinformation being disseminated

![]() Encouraging the CEO to post his own response (“I’m glad to learn you don’t want to lose me, but . . .”), gently chiding community members who have been misbehaving

Encouraging the CEO to post his own response (“I’m glad to learn you don’t want to lose me, but . . .”), gently chiding community members who have been misbehaving

![]() Limiting further responses to the thread to prevent it from going off track again

Limiting further responses to the thread to prevent it from going off track again

![]() Deleting the most egregious comments, or the most objectionable material within them, if necessary

Deleting the most egregious comments, or the most objectionable material within them, if necessary

Rather than vanishing this content down an Orwellian “memory hole,” you can leave behind an explanation of what was deleted and what policy it violated.

![]() Pinning the post containing the organization’s official response to the discussion at the top of the list or otherwise highlighting it

Pinning the post containing the organization’s official response to the discussion at the top of the list or otherwise highlighting it

Interventions of this sort ought to be extremely rare, but it’s better to plan for them than to have to improvise.

Coaching community members for success

Where internal community managers want to be spending more of their time is encouraging positive behaviors. They want employees to use the collaboration network more actively and more productively, while doing their best to eliminate or minimize any frustrations with the social software environment.

Here are some approaches:

![]() Training how to use the social collaboration network: Use in-person training, live webcasts, video tutorials, and company-specific documentation, as well as provide pointers to tutorial content from the vendor or other sources. Offer (re)training when you have major upgrades. All new employees should also get training as part of their company orientation.

Training how to use the social collaboration network: Use in-person training, live webcasts, video tutorials, and company-specific documentation, as well as provide pointers to tutorial content from the vendor or other sources. Offer (re)training when you have major upgrades. All new employees should also get training as part of their company orientation.

![]() Answering questions: When community members ask questions about the best way to accomplish a task on the collaboration network, community managers provide answers or options.

Answering questions: When community members ask questions about the best way to accomplish a task on the collaboration network, community managers provide answers or options.

![]() Making suggestions: When community members waste energy doing something the hard way, the community manager can suggest an easier path, introducing members to a new tool or software feature or introducing them to a person who can help solve the problem.

Making suggestions: When community members waste energy doing something the hard way, the community manager can suggest an easier path, introducing members to a new tool or software feature or introducing them to a person who can help solve the problem.

![]() Sharing success stories: The community manager studies what the most successful users of the collaboration network are doing right and shares clues with all the rest. If, for example, the sales organization within one business unit is able to cut its proposal preparation time in half and win more deals, you want that success to be replicated in other business units.

Sharing success stories: The community manager studies what the most successful users of the collaboration network are doing right and shares clues with all the rest. If, for example, the sales organization within one business unit is able to cut its proposal preparation time in half and win more deals, you want that success to be replicated in other business units.

![]() Mobilizing ambassadors or champions: Successful collaboration network users can be its most effective advocates, regardless of whether they hold any official community management title or authority. Seek out the people who are enthusiastic about telling their stories and sharing tips and encourage them to do more of it. Then treat them like gold.

Mobilizing ambassadors or champions: Successful collaboration network users can be its most effective advocates, regardless of whether they hold any official community management title or authority. Seek out the people who are enthusiastic about telling their stories and sharing tips and encourage them to do more of it. Then treat them like gold.

![]() Encouraging productive outcomes: A good community manager knows when to suggest that a speculative discussion should be turned into a research project to gather more facts and data. Or, if a debate over some issue is going in circles, maybe members should vote on one or more proposed resolutions rather than continuing to chase their tails. Or when an idea for a product or a process change coalesces, the community manager helps with the transition from fruitful brainstorming session to active project.

Encouraging productive outcomes: A good community manager knows when to suggest that a speculative discussion should be turned into a research project to gather more facts and data. Or, if a debate over some issue is going in circles, maybe members should vote on one or more proposed resolutions rather than continuing to chase their tails. Or when an idea for a product or a process change coalesces, the community manager helps with the transition from fruitful brainstorming session to active project.

![]() Listening to feedback: When community members complain that the social tools don’t function as they should or lack important features, community managers consider those remarks seriously. Sometimes they can suggest alternative approaches, or features of the collaboration network that a frustrated user was not aware of. Other times, they will acknowledge the gap in functionality and investigate whether it can be fixed with a customization, a plug-in, or by pushing the social software vendor to include the missing feature in a future release.

Listening to feedback: When community members complain that the social tools don’t function as they should or lack important features, community managers consider those remarks seriously. Sometimes they can suggest alternative approaches, or features of the collaboration network that a frustrated user was not aware of. Other times, they will acknowledge the gap in functionality and investigate whether it can be fixed with a customization, a plug-in, or by pushing the social software vendor to include the missing feature in a future release.

Structuring Collaboration with Groups

Social networking opens up possibilities for ad hoc, spontaneous collaboration, but it also benefits from a little structure. By mapping out your online world, you provide signposts to guide employees toward their most likely collaborators.

Groups or subcommunities are often structured around

![]() Departments or other organizational structures

Departments or other organizational structures

![]() Functions, such as customer support

Functions, such as customer support

![]() Products or product families

Products or product families

![]() Project teams

Project teams

![]() Common roles or disciplines of the participants

Common roles or disciplines of the participants

![]() Communities of practice, specifically geared toward promoting excellence in a process or discipline

Communities of practice, specifically geared toward promoting excellence in a process or discipline

![]() New employees

New employees

![]() Support of the collaboration network itself, particularly for new users

Support of the collaboration network itself, particularly for new users

![]() Groups for off-topic or non–work-related discussions (if allowed at all), meant to build camaraderie, if not productivity

Groups for off-topic or non–work-related discussions (if allowed at all), meant to build camaraderie, if not productivity

I use the term groups here generically. A group on Jive is roughly parallel to a community on IBM Connections. Jive also has spaces, which are sort of super-groups with some additional content management tools, including the ability to contain other spaces, or subspaces. Spaces are often used to represent formal organizational units, such as the human resources department, welcoming visitors with a carefully designed home page including links to important documents, with the activity stream as one widget on the page rather than the central experience.

Yammer has groups for internal discussions but also lets you define multiple networks, with one of the distinctions being that Yammer networks can include external users who have access to that one space but not the rest of the company social network.

Jive, IBM Connections, Podio, and a number of other environments also provide project workspaces as a group type, with task and project management features in addition to discussion and content sharing tools.

Bottom line: These are all subcommunities within the broader community of an enterprise social network. The terminology and the range of group types will vary between platforms, but in every instance, groups exist to focus the activities of the members of your collaboration network. The community manager helps social collaboration participants understand how to interact in these groups to accomplish their business goals.

In the beginning, you want just enough group structure to suggest the possibility of the platform but not so much that users will become lost. As the platform develops, you will want to assert enough control over group proliferation that you don’t wind up with an impenetrable maze.

Controlling the proliferation of groups

One way to encourage more and more productive collaboration is to allow more of it to happen, allowing colleagues to organize their work the way that makes sense to them rather than imposing central planning on all online activities. Typically, participants create new social collaboration groups in one of two ways:

![]() On demand: When collaboration groups can be formed on demand, employees can start getting work done together immediately.

On demand: When collaboration groups can be formed on demand, employees can start getting work done together immediately.

![]() With administrator approval: The alternative to on-demand group creation is to make employees submit a request to create a group or workspace and wait for a system administrator, community manager, or other gatekeeper to act on that request.

With administrator approval: The alternative to on-demand group creation is to make employees submit a request to create a group or workspace and wait for a system administrator, community manager, or other gatekeeper to act on that request.

The dilemma here is not dissimilar to the mess people can make when you make it easier for them to create and share content. I discuss the issues of document sprawl in Chapter 7, and the Jive Community members I turned to for advice tended to cite the issues of content and community proliferation as interrelated management challenges. Especially in a large company, it can be easy to wind up with thousands of groups being formed, many of them overlapping, redundant, or inactive.

When groups proliferate out of control, it becomes more difficult for employees searching or browsing the network to find the right place to ask a question or connect with a subject matter expert. On the other hand, imposing heavy-handed administrative controls can choke off opportunities for collaboration, engagement, and innovation. Successful community strategists don’t all agree on the right approach, but here are some suggestions for reaching middle ground:

![]() Start with on-demand group creation. Allow self-service community creation in the early days of the collaboration network, when promoting adoption and engagement are paramount. Tighten up the process later, if necessary.

Start with on-demand group creation. Allow self-service community creation in the early days of the collaboration network, when promoting adoption and engagement are paramount. Tighten up the process later, if necessary.

![]() Provide an efficient group approval process. Require advance approval but make the approval process as quick and easy as possible.

Provide an efficient group approval process. Require advance approval but make the approval process as quick and easy as possible.

![]() Impose tighter controls for certain types of groups or take them off the menu. For example, some Jive communities restrict the creation of secret groups, which on that platform are invitation-only groups whose content does not show up in search results. Such groups may be warranted for secret projects like negotiating a merger. On the other hand, secret groups can more easily proliferate out of control because they’re invisible.

Impose tighter controls for certain types of groups or take them off the menu. For example, some Jive communities restrict the creation of secret groups, which on that platform are invitation-only groups whose content does not show up in search results. Such groups may be warranted for secret projects like negotiating a merger. On the other hand, secret groups can more easily proliferate out of control because they’re invisible.

![]() Encourage open collaboration. Enterprise community managers should discourage group founders from defaulting to the use of private or secret groups without good reason. Hiding information, or requiring advance permission to join a group, puts roadblocks in the way of collaboration. Most groups benefit more from openness.

Encourage open collaboration. Enterprise community managers should discourage group founders from defaulting to the use of private or secret groups without good reason. Hiding information, or requiring advance permission to join a group, puts roadblocks in the way of collaboration. Most groups benefit more from openness.

![]() Assign ownership of each group. Make sure that every group has an owner responsible for basic community management duties within that space. If the group owner leaves the company or stops actively managing the group, make sure someone else is appointed or else shut it down.

Assign ownership of each group. Make sure that every group has an owner responsible for basic community management duties within that space. If the group owner leaves the company or stops actively managing the group, make sure someone else is appointed or else shut it down.

![]() Create a group for group owners and administrators. Share best practices on community management and maintaining a high level of engagement.

Create a group for group owners and administrators. Share best practices on community management and maintaining a high level of engagement.

![]() Suggest that groups with similar purposes merge. Where you see redundant groups, introduce the owners to each other and encourage them to join forces. You may not want to force the issue. Perhaps they will see important differences in their purpose or organization that aren’t obvious to you. On the other hand, if they simply weren’t aware of each other’s efforts, they may be delighted by the opportunity to team up.

Suggest that groups with similar purposes merge. Where you see redundant groups, introduce the owners to each other and encourage them to join forces. You may not want to force the issue. Perhaps they will see important differences in their purpose or organization that aren’t obvious to you. On the other hand, if they simply weren’t aware of each other’s efforts, they may be delighted by the opportunity to team up.

![]() Monitor activity within groups. Set a minimum threshold, such as six months or a year. If there has been no significant group activity within that period, consider it a candidate to be archived or merged with another similar group. Notify the group owner and members first to see whether anyone steps forward to revive it.

Monitor activity within groups. Set a minimum threshold, such as six months or a year. If there has been no significant group activity within that period, consider it a candidate to be archived or merged with another similar group. Notify the group owner and members first to see whether anyone steps forward to revive it.

Most environments also support a range of options for group membership and privacy. Here are some common patterns.

![]() Open: Anyone can join, instantly.

Open: Anyone can join, instantly.

![]() Controlled membership: Anyone can ask to join, but membership requires the approval of a group owner or administrator.

Controlled membership: Anyone can ask to join, but membership requires the approval of a group owner or administrator.

![]() Invitation-only: You must be invited to join. Depending on how this is set up, any member may be able to issue invitations or that power may be limited to a group owner or administrator.

Invitation-only: You must be invited to join. Depending on how this is set up, any member may be able to issue invitations or that power may be limited to a group owner or administrator.

![]() Secret: Not only are secret groups invitation-only, but they do not show up in search results or group directories.

Secret: Not only are secret groups invitation-only, but they do not show up in search results or group directories.

These levels of access to membership can also be associated with access to content. Group membership is required to view or participate, but may not be required to view content. In some setups, users can follow a group (subscribe to its updates) without becoming a full member.

When membership is restricted for the purpose of providing space for private conversations and information — for example, a collaboration group set up to work on a merger that most employees are not supposed to know about — content from that group should be inaccessible to nonmembers and should not show up in search results.

Reserving the company-wide activity stream for items of company-wide interest

One reason for focusing activity related to a department or a function within a group is to keep the company-wide activity stream from drowning in posts that are of interest to only a subset of community members. The company-wide feed ought to be reserved for items of company-wide interest.

The uses of the company-wide feed are one area where the scale of an organization makes a big difference. In a small business, it may be appropriate for everyone to know everyone else’s business to the point where groups are barely necessary. For very large organizations, the company-wide feed of posts can be almost useless without filtering — almost as if you tried to drink in the full fire hose of conversations on Twitter. There are automated systems that process the full stream, but humans would find Twitter unusable if not for the ability to choose whose updates to follow.

Similarly, social collaboration networks let employees filter the total company activity stream to show just the activity of the people and groups they follow. Some platforms will automatically add supervisors, company leaders, and official news sources such as human resources to that list, but users can also make their own choices.

If you still find that important company announcements are being drowned out by too much irrelevant chatter on the company-wide feed, consider creating an official company news group that only authorized personnel can post to. Make subscribing to that group feed mandatory or strongly encouraged.

Segmenting discussions to cut down on noise

Segmenting discussions according to project, interest, department, or any other organizing principle also cuts down on the noise for the people within that group. It’s like taking a few colleagues into a conference room and closing the door to get some work done, away from the hubbub of the rest of the office. If you’re working on a project together, you can share all your planning documents within that space so all participants know where to find them.

This works best when group content is accessible (open) and searchable even for nonmembers.

Encouraging open group access

As a general principle, group membership and the content within groups ought to be open unless there is a strong reason why privacy is needed. That is the expectation set by social networking, where you make your own decisions about whom to friend or follow, or what groups to join. You curate the connections that make sense, associating with people and entities you find interesting or want to interact with. Openness and transparency of information throughout the organization also serves the knowledge management goals of social collaboration. You want to put content and context to work making the whole organization smarter, and anything that makes it harder for people to access information or make connections is contrary to that goal.

Legitimate reasons for approving members individually may be to limit membership to people who have some professional qualification, such as a law degree or a Project Management Professional (PMP) certification, or who are actively involved in the project served by a project group. You can argue allowing posts from members who don’t share that qualification or purpose would dilute the focus of the group. Maybe you can allow interested nonmembers to follow the group without being members (again, if that option is available).

Another exception to the principle of self-selection is where group membership is automatic or mandatory. For example, all employees of a given department may automatically be made members of a group for departmental collaboration. All new employees may be added to an employee orientation group, with the option of leaving the group once they feel themselves to be sufficiently oriented.

Supporting private groups, where appropriate

You can make openness the default and strongly encourage it in most cases, but in business, there are also many scenarios where privacy is necessary and required. Although private collaboration may be anti-social, your social platform would not be very useful as a business tool if it failed to support private groups, private documents, and private discussions. You wouldn’t want to make the users of your network switch to some other collaboration platform or (gasp) revert to e-mail whenever they need to collaborate on some activity that not everyone in the company should be able to see.

The nomenclature, options, and degrees of privacy vary between platforms, but I use the term private to mean an invitation-only or approval to join required group within which content is not shared with nonmembers. For instance, on the Jive platform, the only information about a private group available to nonmembers is the name of the group. A secret group is similar except that even the name of the group is unlisted in search and the group directory, making it hard for nonmembers to even know it exists unless they get a request to join.

Some private group scenarios include

![]() A group restricted to senior executives who have to be confident in the privacy of their communications if they are to use the collaboration network for discussions of strategy, prior to announcing the strategy to the broader organization

A group restricted to senior executives who have to be confident in the privacy of their communications if they are to use the collaboration network for discussions of strategy, prior to announcing the strategy to the broader organization

![]() A collaboration group devoted to a secret project, such as a potential acquisition, where shared documents may include drafts of the purchase agreement

A collaboration group devoted to a secret project, such as a potential acquisition, where shared documents may include drafts of the purchase agreement

![]() The project group for a super-secret unannounced new product

The project group for a super-secret unannounced new product

![]() A management group devoted to the discussion of personnel matters

A management group devoted to the discussion of personnel matters

![]() Any group that works with documents containing personnel records, health records, or any other data for which access must be restricted on a need-to-know basis for regulatory reasons

Any group that works with documents containing personnel records, health records, or any other data for which access must be restricted on a need-to-know basis for regulatory reasons

![]() Any group that has a strong desire for privacy and doesn’t buy your arguments in favor of openness. Ultimately, you don’t want to presume to know their business better than they do.

Any group that has a strong desire for privacy and doesn’t buy your arguments in favor of openness. Ultimately, you don’t want to presume to know their business better than they do.

On the other hand, companies that have been comfortable in the past using SharePoint team spaces to organize a planned acquisition may find a private group on a collaboration network worthy of the same kind of trust.

The content of private groups can also be accessible to system administrators either within your company or at the cloud data center or hosting facility that maintains your servers.

If you need to put a lot of faith in the privacy of your collaboration system, make sure you understand just how private its private groups are.

Internal community managers play the moderator role, too, but as long as the enterprise social network sets a reasonable standard of professionalism, trolls are rare. Although conservative organizations may fear inappropriate behavior, employees are no more likely to post long rants about management’s incompetence than they are to stand on a chair in the cafeteria and shout the same message. Sure, you can imagine some unbalanced individual announcing her resignation that way. The more common scenario would be someone inadvertently giving offense or violating community rules.

Internal community managers play the moderator role, too, but as long as the enterprise social network sets a reasonable standard of professionalism, trolls are rare. Although conservative organizations may fear inappropriate behavior, employees are no more likely to post long rants about management’s incompetence than they are to stand on a chair in the cafeteria and shout the same message. Sure, you can imagine some unbalanced individual announcing her resignation that way. The more common scenario would be someone inadvertently giving offense or violating community rules. The hazard here is that group members will assume their participation is more private than it actually is. Because they had to get approval to join the group, they may think of what they post as being secret when actually it is visible to any lurker.

The hazard here is that group members will assume their participation is more private than it actually is. Because they had to get approval to join the group, they may think of what they post as being secret when actually it is visible to any lurker.