15

REVENUE AND GROSS MARGINS

CHAPTER INTRODUCTION

Revenue growth is one of the most important drivers in building and sustaining shareholder value. Understanding the drivers of revenue growth, estimating future revenue levels, and achieving sustainable growth rates are some of the most difficult challenges that managers face. This chapter is not intended to be a work on strategy or creative marketing. The objective in this chapter is to enable more discipline and analysis in predicting, driving, and evaluating future revenue projections.

Gross margins are an important indicator of efficiency and competitive position. Product and service pricing, discounting, new product introductions, and competitor challenges all impact gross margins. Design effectiveness and material, manufacturing, and supply chain effectiveness impact the costs of products or services and gross margins.

REVENUE GROWTH: KEY DRIVERS

Figure 15.1 presents a summary of key drivers of revenue growth. Revenue growth arises from two sources: growth resulting from internal activities and growth resulting from acquisitions. Growth resulting from internal activities is often referred to as organic growth. Growth resulting from acquisitions will have very different drivers and economic characteristics from organic growth. The economics of acquired growth are covered in detail in Chapter 23, Analysis of Mergers and Acquisitions. We will focus on organic growth for the remainder of this chapter. Organic growth may result from growth in the overall size of the market, by gaining share from competitors within the market, or by entering new markets.

FIGURE 15.1 Drill‐Down Illustration: Revenue Growth Drivers

Market

Whether chosen by luck or as a result of great strategic thinking, the market that a company serves will be a key driver in determining potential sales growth. Some markets are mature and will grow at slow rates. Others are driven by external forces that will result in high growth rates for a number of years. In markets with high growth rates, even marginal competitors may thrive as all market participants are raised by the rising tide.

Competitive Position

Within a market, the competitive environment and the competitive position of a particular company will determine its ability to grow by increasing market share. A number of factors will determine a company's competitive position, including innovation, customer satisfaction and service, cost and pricing, and the number and size of competitors. Analysis of competitive position should be performed from a customer's perspective. What are the key decision criteria that drive a customer's purchase evaluation and decision? Analysis of competitive position is a relative concept; it is the performance of a company on key factors relative to another firm's offering similar products or services.

Innovation. Innovation can be a leading source of competitive position and should be considered in broad terms and not simply limited to product innovation. In addition to product innovation, firms such as Dell and Amazon have differentiated themselves by radically changing the customer fulfillment and supply chain processes to redefine the business model within an industry. Innovations in marketing or packaging can also produce a significant advantage leading to revenue gains. Innovation was covered in more detail in Chapter 10.

Customer Satisfaction. Customer satisfaction plays a vital role in revenue growth in three ways. First, customer satisfaction will always be a key factor in retaining existing customers. Second, customers that are satisfied with a supplier's performance are likely to offer additional opportunities to that supplier. Third, a strong reputation for customer satisfaction and underlying performance may also lead to opportunities with new customers. Most markets are small worlds, with key customer personnel changing companies. A satisfied customer will likely pull a high‐performing company along with him or her.

Customer Service. Many companies compete by providing outstanding service beyond the traditional customer satisfaction areas such as delivery and quality performance. Working with customers to solve their problems and participating in joint development programs are both examples of investments that build long‐term customer loyalty.

Cost or Pricing Advantages. Price is nearly always a key factor in a customer's procurement decision. The price of a product or service will be driven by the cost of the product, profit targets, and market forces.

The cost of a product or service includes direct and indirect costs. Prices are often set by marking up or adding a profit margin to the cost to achieve a targeted level of profitability or return on invested capital (ROIC). The actual price will have to be set in the context of market forces, including price‐performance comparisons to competitor products.

Suppliers can attain a cost advantage in a number of ways, including achieving economies of scale, process efficiencies, or improvements in quality. Most sophisticated customers look at the total life cycle cost of a procurement decision, of which the product selling price is one component. Other elements of life cycle cost may include installation and training, service, maintenance, and operating and disposal costs. Suppliers that can demonstrate a lower life cycle cost can achieve an advantage over competitors, even if the product price component is more expensive.

Competitor Attributes and Actions. The performance of competitors in the areas that are important to customers will have big impact on a company's ability to grow or even maintain sales. It is not meaningful to project or evaluate revenue projections without a view of competitor intentions, tendencies, and actions. What is the competitor's strategy? How will its financial performance impact its performance in the market? If the competitor has other related businesses, how does that impact its ability to serve this market? What new product or service will the competitor introduce? How will the competitor respond to the introduction of a new product? Do competitors define the market differently? What new competitors may enter the market?

Many revenue projections are prepared without fully considering the answer to these questions. Revenue from new products is assumed to gain market share without reflecting the competitor response. Again, the value in planning is not in the precise quantitative values on the spreadsheet, but rather in the evolution in thinking as a result of the planning process.

Entering New Markets: Opportunities to Broaden or Migrate to Other Segments

Many companies have been successful at growing over extended periods of time. In addition to growing with their primary market and gaining share within that market, companies have found ways to expand the size of the market they serve by moving into adjacent markets. Amazon, for example, leveraged its competencies in distribution and supply chain management to expand its market from books to just about everything!

Projecting and Testing Future Revenue Levels

Since revenue growth is an important driver of economic value, it is critical for managers and investors to fully identify, understand, and evaluate the factors impacting future revenues. Despite the relative importance of revenue compared to other drivers, it often suffers from less disciplined analytical approaches than other drivers such as cost management and operating efficiency. This is due in part to the complexity of the driver and to the significant impact of external forces such as customers, competitors, and economic factors. Managers should develop and improve tools and practices for projecting future revenues and monitor leading indicators of revenue levels. Best practices include:

- Improve revenue forecasting process.

- Prepare multiple views of revenue detail.

- Measure forecast effectiveness.

- Deal effectively with special issues.

Improve Revenue Forecasting Process

Forecasting. In addition to providing a projection of future performance for planning, budgeting, and investor communication, the revenue forecast typically drives procurement and manufacturing schedules and activities. Forecasting revenue is an extremely important activity within all enterprises. Forecasting future business levels is also generally a significant challenge!

Predicting the future is inherently difficult. Having said that, there are a number of things managers can do to improve the forecasting process. First, it is of vital importance that all managers understand the importance of forecasting as a business activity. It impacts customer satisfaction and service levels, costs and expenses, pricing, inventories, and investor confidence, to name a few. Businesses that are predictable and have consistent levels of operating performance will have lower perceived risk, leading to a lower cost of capital. Second, huge gains can be made by measuring forecast effectiveness and assigning responsibility and accountability to appropriate managers. Third, there are a number of techniques that can be applied to improve the effectiveness of forecasts, such as using ranges of expected performance, identifying significant risks and upsides, and developing contingency plans. However, because forecasting involves an attempt to predict the future, it will always be an imperfect activity.

Forecast Philosophy and Human Behavior. The starting point in improving forecasting is to recognize tendencies in human behavior. Most managers are optimistic. They are positive thinkers. They are under pressure to achieve higher levels of sales and profits. They are reluctant to throw in the towel by lowering performance targets. They recognize that decreasing the revenue outlook may result in a decrease in value, necessitate cost and staff reductions or even the loss of their job. Managers who are ultimately responsible for the projections, in most cases the CEO and CFO, must recognize these soft factors and their impact on projections. They must communicate and reinforce the need for realistic and achievable forecasts.

Base Forecast. Many companies have improved their ability to project revenues by using multiple scenarios. A base forecast is developed, which is often defined as the most probable outcome. Managers find it helpful to define an intended confidence level for the base forecast. Is it a 50/50 plan or 80/20? The former would indicate that there is as much chance of exceeding the forecast as falling short. The latter confidence level implies a greater level of confidence in achieving the forecast: there is an 80% chance of meeting or exceeding the forecast. A practical way of defining this would be that 8 out of 10 forecasts would be met or exceeded.

Upside and Downsides. After planning the base case, upside and downside events can be identified. These can be economic factors, competitor actions, or acceleration or delays in new product introductions. For each possible event, managers should identify how they will monitor the possible event and the probability of the event occurring during the plan horizon. In most cases, upside and downside events with high probabilities should be built into the base forecast.

Development of Aggressive and Conservative Forecast Scenarios. Using the base case scenario and potential upside and downside events, managers can prepare an aggressive scenario and a conservative scenario. The aggressive scenario can be achieved if some or all of the upside events materialize, for example if product adoption rates exceed the estimates incorporated into the base case. The conservative scenario contemplates selected downside events. What actions will we take if it becomes apparent that we are trending toward either the aggressive or the conservative scenario? If trending to the aggressive scenario, do we need to accelerate production, hiring, and other investments? If trending to the downside scenario, do we need to reduce or delay investments or hiring? Pedal harder to close the gap?

Identify, Document, and Monitor Key Assumptions. As with any projection, it is important to identify and document key assumptions that support the revenue forecast. Projecting revenues is typically the most difficult element of business planning and involves many assumptions, including factors external to the organization. Key assumptions for revenue projections typically include:

- Market size and growth rate

- Pricing

- Product mix

- Geographic mix

- Competitor actions/reactions

- New product introductions

- Product life cycle of existing products

- Macroeconomic factors, including interest rates, GDP growth, and others

After identifying and documenting these key assumptions supporting revenue projections, these factors must be monitored. Any changes in assumptions must be identified and the potential impact on sales must be quantified and addressed. Critical assumptions should be included on the performance dashboard for revenue growth as illustrated later in this chapter.

Prepare Multiple Views of Revenue Detail

Key dynamics of revenue projections can be identified by reviewing trend schedules of revenue from various perspectives. Table 15.1 is a sample summary of revenue by product. This level of detail identifies contributions from key products and provides visibility into dynamics such as product introduction and life cycles. Other views may be sales by region or geography, customers, and end use market.

TABLE 15.1 Revenue Planning Worksheet: Product Detail ![]()

| Revenue Planning Illustration | |||||

| Actual | Projected | ||||

| Existing Products | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| 1 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 60 | 50 |

| 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3 | 50 | 40 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

| 4 | 30 | 60 | 70 | 90 | 110 |

| Subtotal | 280 | 290 | 270 | 260 | 260 |

| New Product Pipeline | |||||

| 5 | 20 | 35 | 60 | ||

| 6 | 5 | 20 | 35 | ||

| 7 | 20 | 45 | |||

| 8 | |||||

| Subtotal | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 140 |

| Total Sales Projection | 280 | 290 | 295 | 335 | 400 |

| Year‐over‐Year Growth | 3.6% | 1.7% | 13.6% | 19.4% | |

| CAGR: 2017: 2021P | 9.3% | ||||

Another insightful analysis is to evaluate the projections in light of recent performance and comparisons to the plan and to prior year results. Table 15.2 compares year to date (YTD) actual and rest of year (ROY) projected performance to last year and the plan. Since it is comparing the same periods, seasonality is accounted for in the analysis. This forecast needs some explaining! On a year to date basis, revenues are 99% of last year and 92% of plan. However, the forecast revenue for the remainder of the year is 113% of last year and 107% of plan. Coincidentally, the forecast projects that the total year plan will be achieved. There may be some very good reasons for this inconsistency. I sure would like to hear and evaluate them!

TABLE 15.2 Forecast Evaluation Worksheet ![]()

| YTD | ROY | Year | |||||||

| Revenue ($m) | Actual | Last Year | Plan | Fcst | Last Year | Plan | Fcst | Last Year | Plan |

| Product 1 | 1,175 | 1,208 | 1,300 | 1,525 | 1,325 | 1,400 | 2,700 | 2,533 | 2,700 |

| Product 2 | 950 | 985 | 1,100 | 1,350 | 1,102 | 1,200 | 2,300 | 2,087 | 2,300 |

| Product 3 | 1,250 | 1,310 | 1,400 | 1,650 | 1,433 | 1,500 | 2,900 | 2,743 | 2,900 |

| Product 4 | 850 | 825 | 900 | 1,000 | 879 | 950 | 1,850 | 1,704 | 1,850 |

| Product 5 | 733 | 715 | 750 | 800 | 775 | 800 | 1,533 | 1,490 | 1,550 |

| Product 6 | 1,650 | 1,612 | 1,700 | 1,860 | 1,725 | 1,800 | 3,510 | 3,337 | 3,500 |

| Total | 6,608 | 6,655 | 7,150 | 8,185 | 7,239 | 7,650 | 14,793 | 13,894 | 14,800 |

| YTD | ROY | Year | |||||||

| Revenue % | Last Year | Plan | Last Year | Plan | Last Year | Plan | |||

| Product 1 | 97% | 90% | 115% | 109% | 107% | 100% | |||

| Product 2 | 96% | 86% | 123% | 113% | 110% | 100% | |||

| Product 3 | 95% | 89% | 115% | 110% | 106% | 100% | |||

| Product 4 | 103% | 94% | 114% | 105% | 109% | 100% | |||

| Product 5 | 103% | 98% | 103% | 100% | 103% | 99% | |||

| Product 6 | 102% | 97% | 108% | 103% | 105% | 100% | |||

| Total | 99% | 92% | 113% | 107% | 106% | 100% | |||

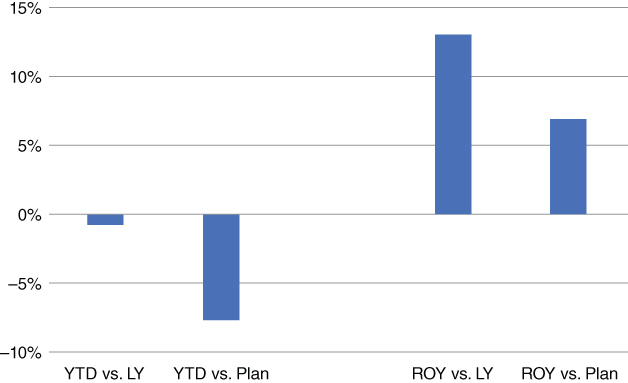

The graphic presentation in Figure 15.2 vividly portrays the inconsistency between actual year to date performance relative to plan and last year, compared to projections for the remainder of the year.

FIGURE 15.2 Revenue Variance

Revenue Change Analysis. A useful way to evaluate revenue projections is to compare them to the prior year and identify significant changes. Each source of significant change can be evaluated and tested. There is a tendency to project future revenues by identifying future sources of revenue growth and adding these increments to existing revenue levels. For example, additional revenues may result from new product introductions or geographic expansion. It is also important to identify factors that will decrease revenues. For example, many industries will experience decreases in average selling prices (ASPs) over time. In addition, all products are subject to life cycles with the eventuality of declining sales levels at some point. Figure 15.3 provides a good visual summary of significant changes in sales from 2018 to 2019.

FIGURE 15.3 Revenue Change Analysis

Market Size and Share Summary. Another view that is useful for evaluating revenue projections is to consider them in the context of the overall market size and growth and market share. Table 15.3 presents the market for Steady Co. For each year, the size of the market is estimated and the growth rate is provided. Sales for each competitor are also estimated, forcing a consideration of competitive dynamics and identification of share gains. In this case, we see that Steady Co.'s 8% growth projected for each year is higher than the market growth. Who will the company take market share from? Why? Is 8% growth each year possible? Is it consistent with the real‐life market dynamics such as product introductions and life cycles, economic factors, and competitive factors?

TABLE 15.3 Market Size and Share Analysis ![]()

| CAGR | ||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2017–2025 | |

| Market Size | 1500 | 1550 | 1600 | 1650 | 1710 | 1770 | 1825 | 1900 | 1975 | 3.5% |

| Growth Rate | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.2% | 3.1% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 3.1% | 4.1% | 3.9% | |

| Sales | ||||||||||

| BigandSlo Co | 700 | 705 | 710 | 712 | 705 | 700 | 680 | 660 | 640 | −1.1% |

| Complex Co | 390 | 400 | 420 | 430 | 450 | 475 | 480 | 500 | 510 | 3.4% |

| Steady Co | 100 | 108 | 117 | 126 | 136 | 147 | 159 | 171 | 185 | 8.0% |

| Fast Co | 10 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | 300 | 370 | 57.0% |

| Other | 300 | 307 | 303 | 282 | 269 | 248 | 256 | 269 | 270 | −1.3% |

| Total | 1500 | 1550 | 1600 | 1650 | 1710 | 1770 | 1825 | 1900 | 1975 | 3.5% |

| Market Share | ||||||||||

| BigandSlo Co | 46.7% | 45.5% | 44.4% | 43.2% | 41.2% | 39.5% | 37.3% | 34.7% | 32.4% | |

| Complex Co | 26.0% | 25.8% | 26.3% | 26.1% | 26.3% | 26.8% | 26.3% | 26.3% | 25.8% | |

| Steady Co | 6.7% | 7.0% | 7.3% | 7.6% | 8.0% | 8.3% | 8.7% | 9.0% | 9.4% | |

| Fast Co | 0.7% | 1.9% | 3.1% | 6.1% | 8.8% | 11.3% | 13.7% | 15.8% | 18.7% | |

| Other | 20.0% | 19.8% | 18.9% | 17.1% | 15.7% | 14.0% | 14.0% | 14.2% | 13.7% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Growth Rate | ||||||||||

| BigandSlo Co | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.3% | −1.0% | −0.7% | −2.9% | −2.9% | −3.0% | ||

| Complex Co | 2.6% | 5.0% | 2.4% | 4.7% | 5.6% | 1.1% | 4.2% | 2.0% | ||

| Steady Co | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | 8.0% | ||

| Fast Co | 200.0% | 66.7% | 100.0% | 50.0% | 33.3% | 25.0% | 20.0% | 23.3% | ||

| Other | 2.3% | −1.3% | −6.9% | −4.6% | −7.8% | 3.2% | 5.1% | 0.4% | ||

| Total | 3.3% | 3.2% | 3.1% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 3.1% | 4.1% | 3.9% |

Measuring Forecast Effectiveness

A very effective way to improve the forecast accuracy is to monitor and track actual performance against the forecasts. Table 15.4 presents the changes made to each quarterly projection over the course of 12 months. It is very effective in identifying biases and forecast gamesmanship. In this example, the analysis surfaces a number of concerns and questions. Note that the actual revenue achieved for each quarter is consistently under the forecast developed at the beginning of that quarter. In addition, shortfalls in one quarter are pushed out into subsequent quarters. However, the team does seem to be able to forecast revenues within one month of the quarter end.

TABLE 15.4 Revenue Forecast Accuracy ![]()

| Month Forecast Submitted: | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Year |

| January | 7,500 | 8,000 | 8,700 | 9,200 | 33,400 |

| February | 7,200 | 8,300 | 8,700 | 9,200 | 33,400 |

| March | 7,000 | 8,500 | 8,700 | 9,200 | 33,400 |

| April | 7,045 | 8,400 | 8,800 | 9,200 | 33,445 |

| May | 8,400 | 8,800 | 9,200 | 33,445 | |

| June | 8,000 | 9,200 | 9,200 | 33,445 | |

| July | 7,076 | 9,200 | 9,200 | 32,521 | |

| August | 9,100 | 9,200 | 32,421 | ||

| September | 8,700 | 9,600 | 32,421 | ||

| October | 8,725 | 9,600 | 32,446 | ||

| November | 9,600 | 32,446 | |||

| December | 9,200 | 32,046 | |||

| January (Final) | 9,250 | 32,096 | |||

| Variance, from beginning of quarter ($) | (455) | (1,324) | (475) | (350) | (1,304) |

| Variance, from beginning of quarter (%) | −6.1% | −15.8% | −5.2% | −3.6% | −4.1% |

Figure 15.4 tracks the evolution of the total year forecast over a 12‐month period. Note that the forecast for the year was not decreased until two quarterly shortfalls were posted.

FIGURE 15.4 Forecast Progression Analysis

Additional Tools for Projecting Revenue

There are additional tools that can be effectively utilized in developing and evaluating revenue projections. These topics are covered in several other chapters, principally in Part Three, Projecting Financial Performance and in Chapter 21, Capital Investment Decisions: Advanced Topics.

Special Issues

There are a number of special circumstances that present challenges in developing and evaluating revenue projections. These include sales projections for new products, chunky or lumpy businesses with uneven sales patterns, and large programs.

Sales Projections for New Products. The development and introduction of new products are always a factor in growing or maintaining sales. Revenue plans for new products must be directly linked to new product development schedules. These schedules must be monitored closely and any changes in the development timeline must be considered in the related revenue projections. A delay in the product schedule will almost certainly delay introduction and the revenue ramp. Product introduction plans must be broad, expanding beyond product development to incorporate key marketing and customer activities. Critical assumptions should be reviewed as well. Any changes in these underlying assumptions should be tested to support revenue plans and even project viability. Examples include changes in key customer performance, economic conditions, and competitor actions.

Chunky and Lumpy Businesses. Some businesses are characterized by large orders resulting in lumpy business patterns from the presence or absence of these orders. These chunks wreak havoc in trend analysis and short‐term projections. Depending on the cost structure and degree of operating leverage, these swings in revenue can result in extremely large fluctuations in profits. Care must be taken in setting expense levels in these situations. It may be appropriate to set expectations and expense levels for a base level of revenue and consider these lumps as upsides. Communicating with investors and other stakeholders about the business variability and disclosing the inclusion of lumpy business are essential to avoid significant fluctuations in the company's valuation and loss of management credibility.

Large Programs and Procurements. In many industries, large procurements, programs, or long‐term contracts are awarded periodically, for example every three years. Revenue changes in these situations are often binary and significant: if the contract is awarded to your firm, significant sales growth will be achieved for the contract period. If unsuccessful, your firm loses the opportunity to obtain that business for that contract period. If a firm loses that business at the end of the contract period, there is a significant decrease to sales. This presents a number of management, financial planning, and stakeholder communication issues.

When pursuing a large procurement opportunity, it is useful to prepare a base forecast without the inclusion of the large procurement and prepare an upside forecast reflecting the award. If a company's existing contracts are up for grabs, consideration should be given to a downside scenario, reflecting conditions if the contract is lost. Investors should have visibility into the presence and expiration dates of significant contracts.

KEY PERFORMANCE MEASURES: REVENUE GROWTH

A number of key performance measures can provide insight into historical trends and future revenue potential.

Sales Growth: Sequential and Year over Year

A critical measure of business performance is simply to measure the rate of growth in sales from one period to another. Table 15.5 illustrates a typical presentation of sales growth rates. Two different measures are frequently used. The first is simply to compute the growth from the previous year. The second measure computes sequential growth rates – that is, from one quarter to another.

TABLE 15.5 Quarterly Sales Trend

| 2018 | 2019 | |||||||||

| $m | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Year |

| Sales | 62 | 64 | 60 | 75 | 261 | 65 | 70 | 58 | 82 | 275 |

| Year‐over‐Year Growth | 5.1% | 6.7% | 11.1% | 8.7% | 7.9% | 4.8% | 9.4% | −3.3% | 9.3% | 5.4% |

| Sequential Growth | −10.1% | 3.2% | −6.3% | 25.0% | −13.3% | 7.7% | −17.1% | 41.4% | ||

While these growth rate measures are important top‐level performance measures, they are of limited usefulness without additional insight and analysis. Some managers and investors will extrapolate past sales growth rates into the future. This works in certain circumstances for a period of time; however, it does not take into consideration the underlying dynamics that will drive future revenues. These factors include market forces, competitive position, innovation, and customer satisfaction discussed earlier in this chapter.

Customer/Competitor Growth Index

The evaluation of a company's performance is best done in the context of competitors, customers, and overall market performance. This is very important in assessing a company's performance in growing sales. For example, if Steady Co. grew 8% last year, the market grew by 3%, and one of the competitors grew 25%, would we consider this acceptable performance?

Comparing growth to rates experienced by key competitors and customers places the company's performance in an appropriate context. It can also be important input to strategic analysis. For example, what are the causes and implications of customer growth exceeding our own? Are we missing potential opportunities to grow with our customers? A summary of comparative growth rates is provided in Figure 15.5. In this case, Steady Co. is growing faster than the market, and at a rate between the company's two largest customers. Steady Co.'s growth rate is ahead of two competitors' rates, but is significantly under Fast Co.'s rate.

FIGURE 15.5 Year‐over‐Year Growth

Percentage of Revenue from New Products

Most companies seek to maintain and grow sales by developing and introducing new products. An important indicator of the success of the new product development and introduction activities is the percentage of revenue from products recently introduced. Some companies would define recently as within two years. Others may shorten the period to reflect shorter product life cycles. This measure is highly susceptible to gaming, so it is critical to have considered definitions, including “What is a new product?”

Customer Retention, Churn Rate, and Lost Customers

Given the cost and difficulty in obtaining new customers, companies must go to great lengths to retain existing customers. Identifying the loss or potential loss of a customer on a timely basis provides immediate visibility into the revenue impact of losing that customer and may afford the company an opportunity to take corrective action. Of course, the reason for losing a customer should be understood, contemplated, and acted upon.

Lost Orders

Companies should track the value and number of orders lost to competitors. Significant trends may signal some change in the competitive environment. Drilling down into lost orders to identify the root cause can also be enlightening. Most companies expect to lose some orders. For example, a high‐end equipment supplier expects to lose some orders to a low‐end supplier where price is a driving factor in the customer's buy decision. However, if the company began to lose orders based on performance or service, the alarm should sound.

Revenue from New Customers

Companies may expect future growth by acquiring new customers. In these cases it would be useful to track revenue derived from sales to new customers. New is defined by individual circumstance, but is frequently defined as revenue derived from customers acquired over the prior 12 months.

Customer Satisfaction

An important factor in maintaining current sales levels and in growing sales is customer satisfaction. An increasing number of companies periodically solicit overall performance ratings from their customers. Many customers have sophisticated supply chain processes that include the evaluation of overall vendor performance. These performance ratings are used as a basis for selecting and retaining vendors.

Key elements of the customer's total experience will include price, quality, delivery performance, and service. Therefore, management should measure these factors frequently. It is important to measure these factors from the customer's viewpoint. For example, the customer may measure quality or service levels differently than the supplier. What matters, of course, is only the customer's perspective.

Past‐Due Orders

Monitoring the number and value of past‐due orders can provide important insight into customer satisfaction. An increase in the level of past‐due orders may indicate a manufacturing or supply problem that resulted in delayed shipments to customers. In addition to tracking (and attacking) the level of past‐due orders, much can be learned by identifying and addressing recurring causes of past‐due orders. Many companies actively “work” past‐due orders. Reducing the level of past‐due sales orders will increase sales and customer satisfaction and reduce inventories and costs.

On‐Time Delivery

On‐time delivery (OTD) is a very important determiner of customer satisfaction. Some companies measure delivery to quoted delivery dates. Progressive companies measure delivery performance against the date the customer originally requested, since that is the date the customer originally wanted the product. This is another measure that can be gamed. Extending the original delivery date or updating the delivery date is counterproductive, but results in a higher OTD performance if the measure is not properly established.

Quality

Measuring the quality of product and other customer‐facing activities is an important indicator of customer satisfaction. Examples include product returns, warranty experience, and the volume of sales credits issued.

Projected Revenue in Product Pipeline

If future growth is highly dependent on new product development and introduction, then management should have a clear view of the revenue potential and project status in each product in the development pipeline. Figure 15.6 is an example of a summary of revenue in the product development pipeline.

FIGURE 15.6 Revenue in Product Development Pipeline

A key benefit to this summary is that development, marketing, sales, and other personnel involved in the introduction of new products have clear visibility of the connection of their activities to future revenue targets. This helps to create linkage in many enterprises where product development teams may not be acutely aware of the timing and potential magnitude of the projects they are supporting. The impact of any delay or acceleration in the development timeline on revenue expectations is easily understood.

Revenue per Transaction

Tracking revenue per transaction can provide important insight into sales trends. Is average transaction or order value increasing or decreasing? Can we capture more revenue per order by selling supplies, related products, service agreements, or consumables? In retail industries, revenue per customer visit is a key revenue metric, and retailers put substantial effort into increasing customer spend per visit by offering related products, cross merchandising, and impulse buy displays.

Revenue per Customer

Reviewing the revenue per customer in total and for key customers can identify important trends. Identifying and tracking sales to top customers is useful in understanding revenue trends, developing future projections, and maintaining an appropriate focus on satisfying and retaining the partners. Analysts must be thoughtful in defining the customer. Many order‐processing systems fragment customers by plant and ship to addresses or divisions, resulting in a less than complete view of the customer's total revenue and activity.

Quote Levels

For certain businesses with long purchasing cycles, tracking the level of open quotes over time can be a leading indicator of future revenue levels. However, not all quotes are created equal. Some may be for budgetary purposes, indicating a long‐term purchase horizon. Others may indicate order potential in the short term. For this reason, quote levels are often summarized by key characteristics to enhance the insight into potential order flow.

Order Backlog Levels

Some businesses have long lead times or order cycles. Customers must place orders well in advance of requested delivery dates. Examples include aircraft, shipbuilding, and large equipment industries. In these industries, the order backlog levels are an important leading indicator of revenue and general business health.

Figure 15.7 provides two views of backlog. In the chart on the top, the backlog by SBU at the end of each quarter is presented. The graph on the bottom presents a phasing of the backlog at Q219 into the future quarter when the revenue is projected to be recorded.

FIGURE 15.7 Backlog Analysis

Anecdotal Input

Nothing beats customer letters or survey responses containing specific feedback. Post them with the quantitative measures and watch the reaction of employees. Many include points actionable by employees at various levels in the company. A few examples:

- “Customer Service never answers the phone. Voice mail messages are not returned for several days.”

- “Service levels have declined. We are contemplating an alternative supplier.”

- “The delay in scheduling installation and training is unacceptable.”

Comprehensive Analysis of Revenue Measures

Collecting and analyzing a broad set of measures supporting revenue growth, lost customers, new product introductions, and other revenue drivers can provide a comprehensive picture into underlying trends and identify issues and opportunities. Table 15.6 illustrates a tool used to collect data that may be useful in the analysis of revenues.

TABLE 15.6 Comprehensive Revenue Measures ![]()

| Performance Measure Collection Worksheets | |||||||||||||

| Revenue | Illustrative | ||||||||||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||||||||

| Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||

| Revenue | 21 | 26 | 18 | 18.7 | 21 | 28 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 30.6 | |||

| Seq Growth | 24% | −31% | 4% | 12% | 33% | −29% | 0% | 10% | 39% | ||||

| Y/Y Growth | 0% | 8% | 11% | 7% | 5% | 9% | |||||||

| Year | 79.4 | 85.7 | 92.6 | ||||||||||

| Y/Y Growth | 8% | ||||||||||||

| Lost Orders | |||||||||||||

| # | 15 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 5 | |||

| $ | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.2 | |||

| % of Sales | 5.7% | 5.8% | 11.1% | 8.0% | 8.1% | 6.4% | 2.5% | 4.5% | 6.8% | 3.9% | |||

| Lost Customers | |||||||||||||

| # | 15 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 5 | |||

| $ | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.8 | |||

| % of Sales | 6.2% | 6.5% | 11.1% | 5.3% | 19.0% | 7.1% | 15.0% | 7.5% | 3.6% | 5.9% | |||

| New Product Sales | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.7 | |||

| % of Total | 14% | 8% | 11% | 11% | 10% | 13% | 19% | 20% | 20% | 15% | |||

| New Customer Sales | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.2 | 3 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 0.5 | |||

| % of Total | 10% | 10% | 17% | 17% | 14% | 13% | 18% | 19% | 10% | 2% | |||

| On‐Time Delivery % | 88% | 75% | 89% | 91% | 84% | 87% | 91% | 92% | 91% | 89% | |||

| Past‐Due Orders $ | 1.7 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.9 | |||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||||||

| Customer Concentration Trend | Customer | $ | Customer | $ | Customer | $ | ||

| 1 | Goliath | 11.0 | Goliath | 12.0 | Goliath | 12.6 | ||

| 2 | DEG | 10.5 | DEG | 11.0 | DEG | 12.0 | ||

| 3 | XYZ | 5.6 | XYZ | 7.0 | XYZ | 9.0 | ||

| 4 | PQR | 4.8 | PQR | 5.0 | PQR | 8.0 | ||

| 5 | MNO | 2.2 | MNO | 3.0 | MNO | 7.0 | ||

| 6 | Upstart | 1.1 | Upstart | 1.2 | Upstart | 1.3 | ||

| 7 | HIJ | 0.8 | HIJ | 0.9 | HIJ | 4.0 | ||

| 8 | TUV | 0.7 | TUV | 0.8 | TUV | 3.0 | ||

| 9 | RST | 0.6 | RST | 0.8 | RST | 2.0 | ||

| 10 | ZAB | 0.5 | ZAB | 0.7 | ZAB | 1.0 | ||

| Total | 0 | 37.8 | 0 | 42.3 | 0 | 59.9 | ||

| % Total Revenue | 47.6% | 49.4% | 64.7% | |||||

| Historical Revenue | |||||||||||

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| 57 | 58 | 60 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 68 | 73.5 | 79.4 | 85.7 | 92.6 | |

| CAGR | 2 Year | 8.0% | |||||||||

| 3 Year | 8.0% | ||||||||||

| 5 Year | 7.7% | ||||||||||

| 10 Year | 5.0% | ||||||||||

| Shading indicates input area | |||||||||||

REVENUE DASHBOARD

Based on the most important drivers and issues impacting current and future revenue growth, a performance dashboard as shown in Figure 15.8 can be created to track and present these measures to managers. The selection of the individual measures to include in the dashboard is an extremely important process. There should be an emphasis on leading and predictive indicators of revenue growth. The measures should focus on the most important drivers and should be changed out over time as appropriate. Properly constructed, this one‐page summary of critical factors is sure to focus the team's attention to appropriate issues and opportunities.

FIGURE 15.8 Revenue Growth and Innovation Dashboard

GROSS MARGINS AND RELATIVE PRICING STRENGTH

It is easy to look at a company with high gross margins and profitability and assume that it is highly efficient from an operating perspective. However, a company may be inefficient but still achieve high margins on the basis of a strong competitive advantage that affords it a premium price. This relative pricing advantage can mask operating inefficiencies and high costs, which can be a source of competitive vulnerability. Over time, relative pricing advantages tend to dissipate, leading to margin erosion unless cost and operating efficiencies are achieved.

Gross margins are primarily a function of two variables, cost of goods sold and pricing. (See Figure 15.9.) Pricing will be driven by a combination of cost and market forces. What typically drives relative pricing strength for a company is a unique product or service offering or an offering with significantly higher performance attributes than competitors' offerings. The leading market indicators for pricing will center on the competitive position and landscape. Factors such as excess industry capacity, aggressive competitor strategies to gain share, and industry health also will play a role.

FIGURE 15.9 Gross Margins and Relative Pricing Strength

Cost of Goods Sold or Cost of Revenues

Costs and operating effectiveness are covered in greater depth in Chapter 16. Costs comprise direct or product cost of goods sold (COGS) and indirect COGS. Product or service COGS generally includes those costs that are directly associated with the product or service. For example, product costs will include the cost of materials, labor, and overhead to assemble or manufacture that product. Other or indirect COGS includes items such as warranty, manufacturing variances, and cost overruns. Service costs include time, materials, and overhead.

Gross margin analysis is also impacted by other factors, including changes in product mix and foreign currency fluctuations. Most well‐run companies examine gross margin trends carefully and identify the factors accounting for changes between periods, as illustrated in Table 15.7.

TABLE 15.7 Gross Margin Analysis ![]()

| Gross Margin Analysis | Variance Analysis | |||||||||

| 2019 | 2020 | Variance | Volume Increase | Pricing Changes | Mix | Cost Increases | Quality Savings | Other | Total | |

| Sales | 125,000 | 126,000 | 1,000 | 2,500 | −1,500 | 1,000 | ||||

| Cost of Sales | 78,000 | 82,000 | −4,000 | −1,560 | −1,500 | −820 | 280 | −400 | −4,000 | |

| Gross Margin | 47,000 | 44,000 | −3,000 | 940 | −1,500 | −1,500 | −820 | 280 | −400 | −3,000 |

| Gross Margin % | 37.6% | 34.9% | −2.7% | 0.0% | −0.8% | −1.2% | −0.7% | 0.2% | −0.3% | −2.7% |

Figure 15.10 presents the analysis in graphical form, highlighting the major changes in gross margin between the two years. This visual presentation enables the viewer to absorb the direction and relative size of each factor contributing to the change.

FIGURE 15.10 Gross Margin Reconciliation

MEASURES OF RELATIVE PRICING STRENGTH

A number of measures can provide visibility into a company's pricing strength.

Average Selling Price

Tracking and monitoring the average selling price (ASP) of products over time is a good indicator of the relative pricing strength of a product in the market. ASP will decline, often rapidly, in highly competitive situations. In many markets, customers expect lower pricing over time as a result of expected efficiencies and savings.

Discounts as a Percentage of List Price

Tracking the level of pricing discounts is a useful indicator of pricing strength that also quantifies the magnitude of any pricing erosion.

Lost Orders

The lost orders measure provides insight into future revenue and pricing trends. Orders lost on the basis of pricing are of particular concern, since they foreshadow a decrease in both revenue and margins.

Product Competitive Analysis

Capturing and monitoring price and performance characteristics of competitive products is a good way to anticipate changes in relative pricing strength. If a competitor introduces a product with better performance attributes, the pricing dynamics in the market are likely to change in very short order.

Market Share

The pricing and performance measures previously described can be combined with the market share analysis and other measures discussed under revenue growth to help form a complete view of the competitive landscape in the context of pricing and gross margins. For example, it is possible that a company is holding firm on pricing but losing market share to lower‐priced competitors.

Gross Margin and Pricing Strength Dashboard

Based on the most important drivers and issues impacting current and future pricing and gross margins, a performance dashboard as shown in Figure 15.11 could be created to provide visibility for managers. Again, the selection of the individual measures to include in the dashboard is extremely important. There should be an emphasis on leading and predictive indicators of competitive forces and pricing. The measures should focus on the most important drivers and should be modified over time as appropriate.

FIGURE 15.11 Dashboard: Gross Margin and Pricing Strength

SUMMARY

Revenue growth and relative pricing strength are among the most important value drivers. Yet in spite of this importance, managers often do a better job in measuring and managing other value drivers. Revenue planning is inherently difficult owing to the complexity of drivers and the impact of external factors. However, managers can greatly increase their ability to build and sustain shareholder value by improving their discipline over projecting, measuring, and growing revenue.

Relative pricing strength is a key driver of value and is realized by holding a strong competitive advantage. Companies that enjoy a strong competitive advantage or have a unique product offering will enjoy strong product margins. It is important to distinguish between strong operating margins resulting from pricing strength and those due to operational efficiency. Over time, competitive advantage and pricing strength often dissipate. This unfavorable impact to margins can be offset by improving operational effectiveness, our topic for Chapter 16.