![]()

Web Services

Up until this point, you have seen how you can use Grails to develop user-oriented web applications. This chapter focuses on how to use web services to expose your application functionality to other applications. You can also use the techniques discussed in this chapter to drive Web 2.0 Ajax enabled web applications, like those discussed in Chapter 8.

Originally, web services grew in popularity as a means for system integration. But with the recent popularity of sites such as Google Maps and Amazon.com, and social networking sites like Facebook, there is an expectation that public APIs should be offered so users can create new and innovative client applications. When these clients combine multiple services from multiple providers, they are referred to as mashups.(See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mashup_(web_application_hybrid) for more information.) They can include command-line applications, desktop applications, web applications, or some type of widget.

In this chapter, you will learn how to expose your application functionality as a Representational State Transfer (REST) web service by extending the Collab- Todo application to provide access to domain objects. This RESTful web service will be able to return either XML or JavaScript Object Notation (JSON), depending on the needs of the client application. This web service will also be designed to take advantage of convention over configuration for exposing CRUD functionality for any Grails domain model, similar to the way Grails scaffolding uses conventions to generate web interfaces. Finally, you will discover how to write simple client applications capable of taking advantage of the web service.

RESTful Web Services

REST is not a standard or specification. Rather, it is an architectural style or set of principles for exposing stateless CRUD-type services, commonly via HTTP. Web services are all about providing a web API onto your web. That is, setting the web services for the application makes the application a source of data that other web applications can use. These web services can be implemented in either REST or SOAP. In the case of SOAP, the data exchange happens in a specialized XML with a SOAP-specific header and body, which adds to the complexity of building web services. Rest supports regular old XML (POX) as well as JSON for data exchange.

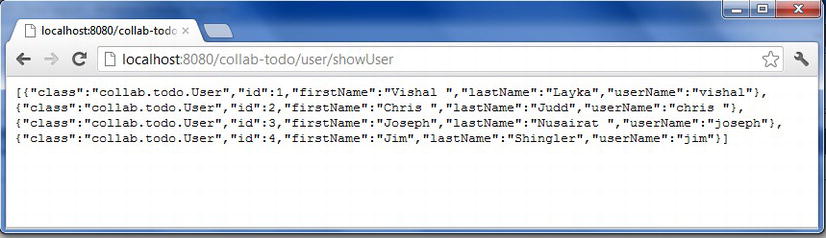

Unlike SOAP, the web services based on REST are resource-oriented. For example, if we implement a web service in the Collab-Todo application that returns an XML representation of the user, the URI to this web service, http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/todo/user , is resource oriented, as the user in the URI is a resource(noun). If the URI was like http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/todo/showuser , it was not resource-oriented, as the showuser is a method (verb) and such a URI is service-oriented. In addition to resource-oriented URI, in the RESTful web service, the access is achieved via standard methods such as HTTP’s GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE. To understand this, we will first implement a web service that is not RESTful. The quickest way to get POX or JSON output from your Grails application is to import the grails.converters.* package and add a closure, as shown in Listing 9-1 and Listing 9-2, with output shown in Figure 9-1 and Figure 9-2, respectively.

Listing 9-1. Implementing a Non-RESTful Web Service for POX Output

import grails.converters.*

class UserController{

def showUser = {

render User.list() as XML

}

...

}

Figure 9-1 . A POX output

Listing 9-2. Implementing a Non-RESTful Web Service for JSON Output

import grails.converters.*

class UserController{

def showUser = {

render User.list() as JSON

}

...

}

Figure 9-2 . JSON output

A RESTful web service in the Collab-Todo application, which we will discuss in later sections, might look like this:

http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/todo/1

In this example, a representation of the Todo object with an id of 1 could get returned as XML, as shown in Listing 9-3.

Listing 9-3. POX Representation of a Todo Object Returned from a RESTful Web Service

<todo id="1">

<completedDate>2012-08-11 11:08:00.0</completedDate>

<createDate>2012-08-11 00:15:00.0</createDate>

<dueDate>2012-08-11 11:08:00.0</dueDate>

<name>Expose Web Service</name>

<note>Expose Todo domain as a RESTful Web Service.</note>

<owner id="1"/>

<priority>1</priority>

<status>1</status>

</todo>

Another alternative might be to return a representation as JSON, like the example shown in Listing 9-4.

Listing 9-4. JSON Representation of a Todo Object Returned from a RESTful Web Service

{

"id": 1,

"completedDate": new Date(1197389280000),

"status": "1",

"priority": "1",

"name": "Expose Web Service",

"owner": 1,

"class": "Todo",

"createDate": new Date(1197350100000),

"dueDate": new Date(1197389280000),

"note": "Expose Todo domain as a RESTful Web Service."

}

In both Listings 9-3 and 9-4, you see that the Todo representation includes all the properties of the object, including the IDs of referenced domain models like owner. The one difference is the lack of the action, or verb. RESTful accessed via HTTP uses the standard HTTP methods of GET, POST, PUT, or DELETE to specify the action. Table 9-1 provides a mapping of CRUD actions to SQL statements, HTTP methods, and Grails URL conventions.

Table 9-1. Relationship Between SQL Statements, HTTP Methods, and Grails Conventions

The relationships described in Table 9-1 are self-explanatory and follow the REST principles, except for the last action of the collection. Because REST is purely focused on CRUD, it doesn’t really address things like searching or returning lists. So the collection is borrowed from the Grails concept of the list action and can easily be implemented by doing a REST read without an ID, similar to the following:

http://localhost/collab-todo/todo

The result of this URL would include a representation of all Todo objects as XML, as shown in Listing 9-5.

Listing 9-5. POX Representation of a Collection of Todo Objects Returned from a RESTful Web Service

<list>

<todo id="1">

<completedDate>2012-08-11 11:08:00.0</completedDate>

<createDate>2012-08-11 00:15:00.0</createDate>

<dueDate>2012-08-11 11:08:00.0</dueDate>

<name>Expose Web Service</name>

<note>Expose Todo domain as a RESTful Web Service.</note>

<owner id="1"/>

<priority>1</priority>

<status>1</status>

</todo>

<todo id="2">

<completedDate>2012-08-11 11:49:00.0</completedDate>

<createDate>2012-08-11 00:15:00.0</createDate>

<dueDate>2012-08-11 11:49:00.0</dueDate>

<name>Expose Collection of Todo objects</name>

<note>Add a mechanism to return more than just a single todo.</note>

<owner id="1"/>

<priority>1</priority>

<status>1</status>

</todo>

</list>

Notice that in Listing 9-5, two Todo objects are returned within a <list> element representing the collection.

Grails provides several features that make implementing a RESTful web service in Grails easy. First, it provides the ability to map URLs. In the case of RESTful web services, you want to map URLs and HTTP methods to specific controller actions. Second, Grails provides some utility methods to encode any Grails domain object as XML or JSON.

In this section, you will discover how you can use the URL mappings, encoding, and the Grails conventions to create a RestController, which returns XML or JSON representations for any Grails domain class, similar to how scaffolding is able to generate any web interface.

As you learned in the previous section, URLs are a major aspect of the RESTful web service architectural style. So it should come as no surprise that URL mappings are involved. But before we explain how to map RESTful web services, let’s look at the default URL mappings.

You can find the URL mappings’ configuration file, UrlMappings.groovy, with the other configuration files in grails-app/conf/. It uses a simple domain-specific language to map URLs. Listing 9-6 shows the default contents of the file.

Listing 9-6. Default UrlMappings.groovy

1. class UrlMappings {

2. static mappings = {

3. "/$controller/$action?/$id?"{

4. constraints {

5. // apply constraints here

6. }

7. }

8. "500"(view:'/error')

9. }

10. }

In case you thought the Grails URL convention was magic, well, it isn’t. Line 3 of Listing 9-6 reveals how the convention is mapped to a URL. The first path element, $controller, as explained in Chapters 4 and 5, identifies which controller handles the request. $action optionally (as noted by the ? operator, similar to the safe dereferencing operator in Groovy) identifies the action on the controller to perform the request. Finally, $id optionally specifies the unique identifier of a domain object associated with the controller to be acted upon.

Listing 9-6 shows how this configuration file maps the default URLs. It is completely customizable if you don’t like the default or if you want to create additional mappings for things such as RESTful web services. Mappings are explained in the next section.

RESTful Mappings

The basic concept behind RESTful URL mappings involves mapping a URL and an HTTP method to a controller and an action.

Listing 9-7. RESTful URL Mapping

static mappings = {

"/user/$id?"(resource:"user")

}

This maps the URI /user onto a UserController. Each HTTP method such as GET, PUT, POST, and DELETE map to unique actions within the controller. You can alter how HTTP methods are handled by using URL Mappings to map to HTTP methods, as shown in Listing 9-8.

Listing 9-8. URL Mappings to Map to HTTP Methods

"/user/$id"(controller: "user") {

action = [GET: "show", PUT: "update", DELETE: "delete", POST: "save"]

}

As we discussed earlier, Grails provides automatic XML or JSON marshalling. However, unlike the resource argument used in Listing 9-7, Grails will not provide automatic XML or JSON marshalling in the case of Listing 9-8, unless you specify the parseRequest argument as shown in Listing 9-9.

Listing 9-9. URL Mappings to Map to HTTP Methods with Auto Marshalling

"/product/$id"(controller: "product", parseRequest: true) {

action = [GET: "show", PUT: "update", DELETE: "delete", POST: "save"]

}

This technique also simplifies making the generic RestController in the next section, because using a common base URL can always be mapped to the RestController. So the URL to invoke a RESTful web service that returns an XML representation like that found in Listing 9-3 would look like this:

http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/rest/todo/1

The URL for returning a JSON representation like that found in Listing 9-4 would look like this:

http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/json/todo/1

You can implement this mapping by adding an additional URL mapping to UrlMappings.groovy. Listing 9-10 shows what the mapping looks like.

Listing 9-10. Using rest Format Type

1. "/$rest/$controller/$id?"{

2. controller = "rest"

3. action = [GET:"show", PUT:"create", POST:"update", DELETE:"delete"]

4. constraints {

5. rest(inList:["rest","json"])

6. }

7. }

Line 1 of Listing 9-10 shows the format of the URL. It includes a required $rest, which is the resulting format type, followed by the required $controller and an optional $id. Because $rest should only allow the two format types we are expecting, line 5 uses an inList constraint much like the constraints discussed in the GORM discussions of Chapter 6. Anything other than a “rest” or a “json” will cause an HTTP 404 (Not Found) error. Line 2 specifies that the RestController will handle any URL with this mapping. Finally, line 3 maps the HTTP methods to Grails conventional actions on the RestController.

Content negotiation is a mechanism defined in the HTTP specification that makes it possible to deal with different incoming requests to serve different versions of a resource representation at the same URI. Grails has built-in support for content negotiation using either the HTTP Accept header, an explicit format request parameter, or the extension of a mapped URI.

With the content negotiation, a controller can automatically detect and handle the content type requested by the client. Before you can start dealing with content negotiation, you need to tell Grails what content types you wish to support. By default, Grails comes configured with a number of different content types within grails-app/conf/Config.groovy using the grails.mime.types setting, as shown in Listing 9-11.

Listing 9-11. Default Content Types

grails.mime.types = [ xml: ['text/xml', 'application/xml'],

text: 'text-plain',

js: 'text/javascript',

rss: 'application/rss+xml',

atom: 'application/atom+xml',

css: 'text/css',

csv: 'text/csv',

all: '*/*',

json: 'text/json',

html: ['text/html','application/xhtml+xml']

]

The above bit of configuration allows Grails to detect to format of a request containing either the 'text/xml' or 'application/xml' media types as simply 'xml'.

Content Negotiation using the Accept Header

Every browser that conforms to the HTTP standards is required to send an Accept header. The Accept header contains information about the various MIME types the client is able to accept. Every incoming HTTP request has a special Accept header that defines what media types (or mime types) a client can “accept.” Listing 9-12 illustrates an example of a Firefox Accept header.

Listing 9-12. Example of Accept Header

text/xml, application/xml, application/xhtml+xml, text/html;q=0.9,

text/plain;q=0.8, image/png, */*;q=0.5

Grails parses this incoming format and adds a property to the response object that outlines the preferred response format.

To deal with different kinds of requests from Controllers, you can use the withFormat method, which acts as kind of a switch statement, as shown in Listing 9-13.

Listing 9-13. Using withFormat Method

import grails.converters.XML

class UserController {

def list() {

def users = User.list()

withFormat {

html userList: users

xml { render users as XML }

}

}

}

If the preferred format is html, Grails executes the html() call only. If the format is xml, the closure is invoked and an XML response is rendered. When using withFormat, make sure it is the last call in your controller action, as the return value of the withFormat method is used by the action to dictate what happens next. The request format is dictated by the CONTENT_TYPE header and is typically used to detect if the incoming request can be parsed into XML or JSON, while the response format uses the file extension, format parameter, or Accept header to attempt to deliver an appropriate response to the client. The withFormat available on controllers deals specifically with the response format. To add logic that deals with the request format, use a separate withFormat method on the request, as illustrated in Listing 9-14.

Listing 9-14. Using withFormat with Request

request.withFormat {

xml {

// read XML

}

json {

// read JSON

}

}

Content Negotiation with the Format Request Parameter

Another mechanism of content negotiation is to use the format request parameter, which is used to override the format used in the request headers by specifying a format request parameter:

/user/list?format=xml

You can also define this parameter in the URL Mappings definition:

"/user/list"(controller:"user", action:"list") {

format = "xml"

}

Content Negotiation with URI Extensions

Grails also supports content negotiation using URI extensions. For example, suppose you have the following URI:

/user/list.xml

In this case, Grails will remove the extension and map it to /user/list instead, while simultaneously setting the content format to xml based on this extension. This behavior is enabled by default; to turn it off, set the grails.mime.file.extensions property in grails-app/conf/Config.groovy to false:

grails.mime.file.extensions = false

RestController

Because Grails already has conventions around CRUD as well as dynamic typing provided by Groovy, implementing a generic RESTful controller that can return XML or JSON representations of any domain model is relatively simple. We’ll begin coverage of the RestController by explaining the common implementation used by all actions. We’ll then explain each action and its associated client, which calls the RESTful service.

The common functionality of the RestController is implemented as an interceptor, as discussed in Chapter 5, along with two helper methods. Listing 9-15 contains a complete listing of the common functionality.

Listing 9-15. RestController

import static org.apache.commons.lang.StringUtils.*

import org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.InvokerHelper

import org.codehaus.groovy.grails.commons.GrailsDomainClass

import Error

/**

* Scaffolding like controller for exposing RESTful web services

* for any domain object in both XML and JSON formats.

*/

class RestController {

private GrailsDomainClass domainClass

private String domainClassName

// RESTful actions excluded

def beforeInterceptor = {

domainClassName = capitalize(params.domain)

domainClass = grailsApplication.getArtefact("Domain", domainClassName)

}

private invoke(method, parameters) {

InvokerHelper.invokeStaticMethod(domainClass.getClazz(), method, parameters)

}

private format(obj) {

def restType = (params.rest == "rest")?"XML":"JSON"

render obj."encodeAs$restType"()

}

}

The beforeInterceptor found in Listing 9-15 is invoked before any of the action methods are called. It’s responsible for converting the $controller portion of the URL into a domain class name and a reference to a GrailsDomainClass, which are stored into private variables of the controller. You can use the domainClassName later for logging and error messages. The name is derived from using an interesting Groovy import technique. Since the controller in the URL is lowercased, you must uppercase it before doing the lookup. To do this, use the static Apache Commons Lang StringUtilscapitalize() method. Rather than specifying the utility class when the static method is called, an import in Groovy can also reference a class, making the syntax appear as if the static helper method is actually a local method. A reference to the actual domain class is necessary so the RestController can call dynamic GORM methods. Getting access to that domain class by name involves looking it up. However, because Grails domain classes are not in the standard classloader, you cannot use Class.forName(). Instead, controllers have an injected grailsApplication with a getArtefact() method, which you can use to look up a Grails artifact based on type. In this case, the type is domain. You can also use this technique to look up controllers, tag libraries, and so on.

![]() Note The RestController class is framework-oriented, so it uses some more internal things such as grailsApplication.getArtefact() and InvokerHelper to behave generically. If you get into writing Grails plugins, you will use these type of techniques more often than in normal application development.

Note The RestController class is framework-oriented, so it uses some more internal things such as grailsApplication.getArtefact() and InvokerHelper to behave generically. If you get into writing Grails plugins, you will use these type of techniques more often than in normal application development.

In Listing 9-15, the helper methods are the invoke() method and format() method. The invoke() method uses the InvokerHelper helper class to simplify making calls to the static methods on the domain class. The methods on the domain class that are invoked by the RestController are all GORM-related. The format method uses the $rest portion of the URL to determine which Grails encodeAsXXX() methods it will call on the domain class. Grails includes encodeAsXML() and encodeAsJSON() methods on all domain objects.

There is one other class involved in the common functionality, and that is the Error domain class found in Listing 9-16.

Listing 9-16. Error Domain Class

class Error {

String message

}

Yes, the Groovy Error class in Listing 9-16 is a domain class found in the grails-app/domain directory. Making it a domain class causes Grails to attach the encoding methods, therefore enabling XML or JSON to be returned if an error occurs during the invocation of a RESTful web service.

The show action has double duty. It displays both a single domain model and a collection of domain models. Listing 9-17 exhibits the show action implementation.

Listing 9-17. show Action

def show = {

def result

if(params.id) {

result = invoke("get", params.id)

} else {

if(!params.max) params.max = 10

result = invoke("list", params)

}

format(result)

}

In Listing 9-17, you should notice that the action uses params to determine if an ID was passed in the URL. If it was, the GORM get() method is called for that single domain model. If it wasn’t, the action calls the GORM list() method to return all of the domain objects. Also, notice that just like scaffolding, the action only returns a maximum of 10 domain objects by default. Using URL parameters, you can override that, just like you can with scaffolding. So adding ?max=20 to the end of the URL would return a maximum of 20 domain classes, but it does break the spirit of REST.

Listing 9-18 contains example code of a client application that calls the show action and returns a single domain model.

Listing 9-18. RESTful GET Client (GetRestClient.groovy)

import groovy.util.XmlSlurper

def slurper = new XmlSlurper()

def url = " http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/rest/todo/1 "

def conn = new URL(url).openConnection()

conn.requestMethod = "GET"

conn.doOutput = true

if (conn.responseCode == conn.HTTP_OK) {

def response

conn.inputStream.withStream {

response = slurper.parse(it)

}

def id = response.@id

println "$id - $response.name"

}

conn.disconnect()

There are a couple of things to notice in Listing 9-18. First, the example uses the standard Java URL and URLConnection classes defined in the java.net package. This is true of all client applications through the rest of the chapter. You could also use other HTTP client frameworks, such as Apache HttpClient.1 Second, notice that the request method of GET was used. Finally, the Groovy XmlSlurper class was used to parse the returned XML. This allows you to use the XPath notation to access things such as the name element and the id attribute of the result.

Because DELETE is so similar to GET, both the action code and the client code are similar to that shown in the previous show action section. Listing 9-19 shows the delete action implementation.

Listing 9-19. delete Action

def delete = {

def result = invoke("get", params.id);

if(result) {

result.delete()

} else {

result = new Error(message: "${domainClassName} not found with id ${params.id}")

}

format(result)

}

In Listing 9-19, the GORM get() method is called on the domain class. If it is found, it is deleted. If it isn’t, it will return an error message. Listing 9-20 shows the client code that calls the delete RESTful web service.

Listing 9-20. RESTful DELETE Client (DeleteRestClient.groovy)

def url = " http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/rest/todo/1 "

def conn = new URL(url).openConnection()

conn.requestMethod = "DELETE"

conn.doOutput = true

if (conn.responseCode == conn.HTTP_OK) {

input = conn.inputStream

input.eachLine {

println it

}

}

conn.disconnect()

The only differences between Listing 9-20 and Listing 9-18 are that the request method used in Listing 9-20 is DELETE, and instead of using the XmlSlurper, the contents of the result are just printed to the console, which is either an XML or JSON result of the deleted domain.

A POST is used to update the existing domain models in the RESTful paradigm. Listing 9-21 shows the implementation of the method that updates the domain models.

Listing 9-21. update Action

def update = {

def result

def domain = invoke("get", params.id)

if(domain) {

domain.properties = params

if(!domain.hasErrors() && domain.save()) {

result = domain

} else {

result = new Error(message: "${domainClassName} could not be saved")

}

} else {

result = new Error(message: "${domainClassName} not found with id ${params.id}")

}

format(result)

}

Like previous examples, Listing 9-21 invokes the GORM get() method to return the domain model to update. If a domain model is returned, all the parameters passed from the client are copied to the domain. Assuming there are no errors, the domain model is saved. Listing 9-22 shows a client that calls the POST.

Listing 9-22. RESTful POST Client (PostRestClient.groovy)

def url = " http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/rest/todo "

def conn = new URL(url).openConnection()

conn.requestMethod = "POST"

conn.doOutput = true

conn.doInput = true

def data = "id=1¬e=" + new Date()

conn.outputStream.withWriter { out ->

out.write(data)

out.flush()

}

if (conn.responseCode == conn.HTTP_OK) {

input = conn.inputStream

input.eachline {

println it

}

}

conn.disconnect()

Notice that Listing 9-22 uses a POST method this time. Also, pay attention to the fact that the data is passed to the service as name/value pairs separated by &s. At a minimum, you must use the id parameter so the service knows on which domain model to operate. You can also append other names to reflect changes to the domain. Because this is a POST, the container automatically parses the name/value pairs and puts them into params. The result will either be an XML or a JSON representation of the updated domain.

Finally, the most complicated of the RESTful services: the create service. Listing 9-23 shows the implementation.

Listing 9-23. create Action

def create = {

def result

def domain = InvokerHelper.invokeConstructorOf(domainClass.getClazz(), null)

def input = ""

request.inputStream.eachLine {

input += it

}

// convert input to name/value pairs

if(input && input != '') {

input.tokenize('&').each {

def nvp = it.tokenize('='),

params.put(nvp[0],nvp[1]);

}

}

domain.properties = params

if(!domain.hasErrors() && domain.save()) {

result = domain

} else {

result = new Error(message: "${domainClassName} could not be created")

}

format(result)

}

Listing 9-23 begins by using InvokerHelper to call a constructor on the domain class. Unlike POST, PUT’s input stream of name/value pairs is not automatically added to the params. You must do this programmatically. In this case, two tokenizers are used to parse the input stream. After that, the rest of the implementation follows the update example found in Listing 9-21. Listing 9-24 demonstrates a client application that does a PUT.

Listing 9-24. RESTful PUT Client (PutRestClient.groovy)

def url = " http://localhost:8080/collab-todo/rest/todo "

def conn = new URL(url).openConnection()

conn.requestMethod = "PUT"

conn.doOutput = true

conn.doInput = true

def data = "name=fred¬e=cool&owner.id=1&priority=1&status=1&"+

"createDate=struct&createDate_hour=00&createDate_month=12&" +

"createDate_minute=15&createDate_year=2012&createDate_day=11"

conn.outputStream.withWriter { out ->

out.write(data)

out.flush()

}

if (conn.responseCode == conn.HTTP_OK) {

input = conn.inputStream

input.eachLine {

println it

}

}

conn.disconnect()

Listing 9-24 is nearly identical to Listing 9-22, except that the PUT request method and a more complicated set of data are passed to the service. In this example, the data includes the created date being passed. Notice that each element of the date/time must be passed as a separate parameter. In addition, the createDate parameter itself must have a value of struct. The result is either an XML or JSON representation of the created domain object.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned about the architectural style of RESTful web services, as well has how to expose domain models as RESTful web services. As you build your applications, look for opportunities to expose functionality to your customers in this way. You may be amazed at the innovations you never even imagined. In Chapter 13, you will see one such innovation of a Groovy desktop application.