4

PARTICIPATORY LANDSCAPE

GOVERNANCE

Context and rationale

This chapter builds on AHI experiences in participatory watershed management, but focuses on the social and institutional dimensions of natural resource management challenges at landscape level. As mentioned in Chapter 3, time–space interactions between plots and common-pool resources, lateral flows of materials (water, nutrients, pests), and interdependence between users in terms of resource access and management, require decision-making and intervention strategies beyond the farm level (Johnson et al., 2001; Knox et al., 2001; Ravnborg and Ashby, 1996). Therefore, in addition to emphasizing effective participation and integrated decision-making to acknowledge linkages among diverse system components and users, processes for governing biophysical processes connecting different land users and interest groups are sorely needed. This is particularly true where demographic, economic, and ecological dynamics have outpaced the ability of customary systems of natural resource management to cope with change. Efforts to foster collective action and govern natural resource decision-making should therefore be considered a fundamental component of any watershed management process—particularly where local motivations (e.g., issues that are of deep concern to at least some land users) do not translate into effective solutions in the absence of intervention.

Social and political dimensions of NRM are very poorly addressed in NRM research and development programs. These include a complex social fabric within communities based on differences of gender, kinship, tribe, wealth status, religion, and politico-administrative divisions. They also include internal polarization around “appropriate” land-use practices based on economic or other interests. The divergent “stakes” that lend a political dimension to landscape management generally go unrecognized. The intractability of many natural resource management challenges—which manifest as inherently biophysical on the surface—may in fact result from underlying epistemological, cultural, and political factors (German et al., 2010; Leach et al., 1999). These include divergent interests associated with either a mismatch between efforts required of individuals to implement an innovation and the benefits they anticipate from them, or from land-use practices for which benefits accrue to some land users and costs to others. At times, the prevalence of practices that carry negative consequences for other land users may be owing to limited awareness of the consequences of current behavior on others or on environmental services of local importance (e.g., water). However, as this chapter shows, it is often owing to the fact that important benefits accrue to those households continuing practices viewed as detrimental by others. These divergent interests often create latent conflict that leads to a breakdown in communication among those who most need to plan collectively to address the problem.

Such divergent interests need to be taken into consideration in the approaches used by NRM research and development organizations. The tendency, however, is to focus on technological solutions to NRM problems and on individual decision-making on which solutions to test. Who participates and who benefits are questions that are largely left unaddressed, as are those issues that require collective or negotiated decisions in order to be effectively addressed. Such deficiencies may create further inequities, undermine the effective resolution of landscape-level NRM problems, or result in lost synergies between social capital development, technological innovation, and natural resource governance.

As this chapter and the wider literature illustrates, collective action and participatory governance processes are required to regulate rights and responsibilities to common property resources and public goods such as water, communal grazing lands, and community forests (Gaspart et al., 1998; Gebremedhin et al., 2002; Munk Ravnborg and Ashby, 1996; Ostrom, 1990; Scott et al., 2001). Collective solutions are also required to manage biophysical processes that do not respect farm boundaries, such as control of pests and excess run-off, minimizing damage caused from free grazing, or managing the effects of boundary vegetation on adjacent farms (Munk Ravnborg et al., 2000). Collective action is likewise necessary to negotiate joint investments and technological innovations for enhanced productivity or income, for example to enable the sharing of transaction costs of organizing or marketing, and to regulate benefits capture from outside interventions (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002).

When developing and testing social and institutional innovations to be tested in this arena, it was necessary to ground the design of interventions on established theoretical understandings of the foundational elements to effective local governance of natural resources. For this, we drew heavily on the work of Eleanor Ostrom (1990). Ostrom's work was instrumental in countering the theory laid out in Hardin's The Tragedy of the Commons (1968), where it is posited that open access and unrestricted demand for a finite good in common pool resources will inevitably cause over-exploitation and resource degradation—thus requiring enclosure or privatization of the commons. The Ostrom tradition has clarified how groups of users can create institutions to fulfill a set of functions required for managing resources sustainably—namely, exclusion, allocation among users, and establishing conditions of transfer. By studying a large number of case studies from traditional common property regimes across the world, they were able to distill a set of features common to institutions that have proven effective in managing common pool resources sustainably (Ostrom, 1990; see also Pandey and Yadama, 1990; Wittayapak and Dearden, 1999). These include:

1. A clearly defined community of resource users and clearly defined resource (both of manageable size).

2. The presence of a set of clearly defined “collective choice rules” developed voluntarily by users to clarify the rules of the game (e.g., what is permissible, what contributions are required in exchange for use rights, and sanctions for non-compliance) and which help to balance the costs of collective action with the benefits derived from it.

3. Sanctions that are “graduated” or matched to the level of the offense.

4. Systems for monitoring the status of the resource and for adaptive management (to enable rules to be modified as need arises).

5. Conflict resolution systems.

Yet despite the rich body of research and accumulated wisdom on customary systems of natural resource governance emanating from the Ostrom tradition, efforts to apply these principles to contemporary natural resource management challenges are hard to come by. To what extent can negotiation support processes enable local interest groups to see the value of collective action or to overcome the silences that characterize latent conflicts and thus contribute to inaction? To what extent are the principles of Ostrom's “self-governing institutions” relevant to contemporary problems where institutions are insufficient for addressing natural resource management problems of local concern? And are they effective in building solutions that lie beyond common pool resources? To what extent can external research and development institutions move beyond generic forms of support to undifferentiated communities towards “more explicit partiality” (Leach et al., 1999)? These are the questions that the body of work presented in this chapter attempted to address.

The following section presents a typology of natural resource management issues, constructed based on experience in supporting local land users to identify and address natural resource management issues requiring collective solutions. The three sections that follow describe different approaches employed to strengthen local governance of these issues, and the closing sections synthesize lessons learned and remaining challenges.

Toward a typology of issues requiring improved landscape governance

In AHI watershed sites, two broad scenarios were found that require efforts to foster collective decision-making among divergent local interest groups. The first involves NRM issues that remain unresolved owing to inadequate collective action among community members. The second and more intractable scenario involves local interest groups with divergent views and interests around the issue. The nature of these issues determines the type of strategies most effective for improving equitable landscape governance. For a brief illustration of the two scenarios as they apply to vertebrate pest control, see Box 4.1.

BOX 4.1 CONTROLLING PORCUPINE IN AREKA: TWO DETERRENTS TO COLLECTIVE ACTION

Crested porcupine was the most important vertebrate pest identified during the problem diagnosis stage of AHI in Gununo watershed. Porcupines cause tremendous crop losses for Areka farmers. Porcupines eat primarily maize cobs, followed by roots of sweet potato, leaves of cabbage, roots and tubers of yams, potato, cassava, haricot bean, and seeds of field pea. As mentioned in Chapter 3, farmers spend their nights keeping watch over their fields against porcupines during the growing season, causing loss of sleep and frequent visits to the health center for weather-induced disease. The porcupine case is an interesting collective action challenge because it applies to each of the two scenarios, as follows:

A. The problem remains unresolved owing to inadequate collective action

As porcupines travel up to 14 km at night in search of food, crossing many farm boundaries, efforts to kill or trap them by individual farmers are largely ineffective. Its management must extend beyond farm and watershed boundaries, even up to district level, to minimize the effect of re-infestation from adjacent villages or Peasant Associations (PAs). The large areas over which re-infestation may occur makes individualized efforts at porcupine control largely ineffective.

B. Divergent interests of local stakeholder groups hinder the quest for easy solutions

There is a second challenge to catalyzing collective action for porcupine control, namely, the presence of local interest groups here defined by the level at which different households are affected by porcupine. Farmers growing crops vulnerable to porcupine damage are more eager to engage in collective solutions than those growing crops less susceptible to attack (for example, teff, wheat, barley, and enset). For this purpose, tools for awareness creation were used to encourage high levels of collective action across several PAs. Community meetings were called to raise awareness of the fact that households less affected today may be susceptible in the future if they shift to crops eaten by porcupine. By-laws were also developed through participatory dialogue among the different interest groups to hold individual households accountable to collective interests.

In recognition of these barriers to collective action, combined strategies were used both to mobilize the overall community (megaphones, local music, and awareness creation) and to foster equitable solutions between the local interest groups (negotiation support, participatory by-law reforms). When applied concurrently, these strategies were instrumental in reducing crop losses, labor burden, and illness resulting from long nights spent policing fields against the pest among PA residents.

We now delve into each of the two scenarios in greater detail as a means of illustrating the diversity of issues that falls within each, as well as the sub-classes into which each of these issues may be further differentiated.

Scenario 1: Issues remain unresolved owing to inadequate collective action

In this scenario, either the solution is not fully effective when carried out by individuals, or in the absence of collective action the issue simply cannot be solved. The following types of NRM problems are less effective when done on an individual basis:

• Control of many pest and weed species that easily spread across farm boundaries (as in Box 4.1).

• Controlling run-off and soil erosion, for which greater levels of collective action imply more effective solutions, owing to “aggregate effects” of many households implementing soil conservation structures (Box 4.2).

• Nursery management, where “free riders” (who fail to invest time according to agreements) undermine incentives of others to engage in collective action (Box 4.3).

BOX 4.2 CONTROLLING RUN-OFF IN KAPCHORWA DISTRICT, UGANDA: FROM “LONE RANGER” TO COLLECTIVE ACTION

Mr. Akiti Alfred of Tolil village in the Benet Sub-County has, in recent years, been constructing soil and water conservation structures in an attempt to control the run-off in his fields. However, his fields continued to be affected by the ever-increasing run-off from his upslope neighbor's fields. He approached one of his neighbors from the adjacent village, Mr. Kissa Peter, and told him about the continued run-off affecting his fields. Mr. Kissa said that he was also experiencing similar problems of soil degradation and declining crop yields and that his crop yields of maize had reduced by about 60 percent. Mr. Kissa further explained that there were other farmers in other villages experiencing similar problems, despite the fact that they had adopted soil conservation structures in their fields. From this experience, Mr. Akiti approached two other neighbors about the problem and discovered that they were equally concerned. Mr. Kissa and these other neighbors advised him to call for an urgent village meeting to share with other farmers ideas on how they could deal with the run-off affecting livelihoods of the entire community. A meeting was convened in the Tolil village to discuss strategies for controlling run-off.

In the village-level meeting, it was resolved that a broader meeting should be held among four of the most heavily affected villages. In that meeting, residents of the four villages resolved to form Village Watershed Committees to take responsibility for common NRM problems. New by-laws governing common NRM issues were then formulated, and soil and water conservation technologies used to implement agreed by-laws. The Kapchorwa District Landcare Chapter continues to serve as a multi-stakeholder platform to backstop and support communities in their articulation and resolution of this and other common NRM concerns.

BOX 4.3 NURSERY MANAGEMENT IN GINCHI: LEARNING THROUGH ITERATIVE PHASES OF IMPLEMENTATION AND ADJUSTMENT

Extensive forest clearing for cultivation and over-grazing, and unregulated exploitation of forests for fuelwood and construction materials in the absence of reforestation efforts at household or community level, has led to the depletion of forest resources in the watershed. As an integral part of integrated watershed management, introducing multi-purpose tree species in Galessa watershed was seen as a priority of both farmers and the site team. An action research approach was employed to develop, test, and improve upon the approach over time.

Testing of approaches

Approach 1—A meeting was organized and farmers were reminded about the concern they ranked very highly during the participatory watershed diagnosis—namely, loss of indigenous tree species. Farmers were asked to identify the most preferred tree species in their locality. One tree nursery was established in the watershed for the whole watershed community in 2004/2005. The nursery was to be managed collectively by the entire watershed community.

Outcome 1—The performance and survival rate of seedlings in the nursery was poor (54.7 percent) owing to poor nursery management. This was in turn owing to lack of agreements on communal work (e.g., how responsibilities and benefits would be shared), lack of knowledge on raising seedlings, and lack of nursery tools.

Approach 2—In 2005/2006, those farmers with an interest in raising seedlings in each village were organized in groups and a single nursery was established at Legbatebo village with subdivisions into blocks corresponding to different villages, to clarify ownership. Collective choice rules were developed to specify how responsibilities for nursery maintenance would be shared and seedlings distributed. Trainings were given and continuous follow-up was made to reinforce local agreements.

Outcome 2—While the number of participating farmers declined (from 86 to 36), the performance and survival rate of seedlings was very good (97 percent) owing to the manageable size of the group and the local governance arrangements put into place.

The lessons learned from this experience included: (i) the need to have a manageable number of farmers to work together for nursery management; (ii) the importance of developing collective choice rules through the full participation of all participants; and (iii) the importance of ensuring these rules are enforced. Each of these is a key to sustaining collective action, as they assist in clarifying both responsibilities and the distribution of benefits.

Examples of natural resource management problems that generally cannot be solved in the absence of collective action include the following:

• Extensive use of outfields, in which free grazing traditions (including seasons of restricted and/or open access grazing) will subject any innovation to collective agreement.

• Extensive use of outfields, in which traditional beliefs governing the use of the common property resource prohibit any innovation (Box 4.4).

• Controlling extreme run-off, which requires trenches across the entire landscape and agreement on the location of common waterways which must pass through farmers’ fields (to divert excess water from fields).

BOX 4.4 LOCAL BELIEFS GOVERNING THE USE OF COMMUNAL GRAZING AREAS IN AREKA

The communal grazing area in Areka covers approximately 60 ha. Residents of Gununo watershed say that the land was once privately owned but transferred to the community for grazing purposes. At that time, the landowner called a community meeting for the purpose of handing over the land to the community and about 100 cattle were slaughtered for the celebration. On this occasion, the owner made the community promise not to utilize the land for any purpose other than communal grazing. At that time, the land was productive owing to the low livestock population. However, now the land is utilized unproductively, scarcely supporting the large livestock population. When exploring options for intensification, the community strongly resisted touching the grazing area. One man whose farmland had encroached onto the communal grazing land in the past died, making the community believe that they will be cursed if they do the same. These beliefs may have an adaptive logic, such as ensuring access to pasture irrespective of household landholdings and supporting social safety nets (through the complex livestock sharing mechanisms mentioned in Chapter 3). However, its productive value is strongly undermined through overgrazing – suggesting the need for some form of collective action.

Scenario 2: Divergent interests of local interest groups hinder easy solutions

The issues that fall within this second category remain unresolved either because collective action requires that some individuals contribute or sacrifice more than they are likely to benefit from collective action, or because one party is benefiting while another party(ies) is harmed by the status quo. Problems stemming from the latter often involve latent or overt conflict and a resulting breakdown in communication.

Local interest groups or stakeholders for Scenario 2 may be defined in much the same way:

(i) Some households are more affected than others, and the motivation to participate in collective action varies among most and least affected households. Examples include the following:

• Controlling excess run-off, where upslope farmers benefit less from soil conservation structures because they are less affected by the damage caused by excess run-off from upslope.

• Crop destruction from porcupine, since some households grow crops that lure this pest (e.g., sweet potato, maize, haricot and faba bean), while others do not grow crops attractive to porcupine (please refer to Box 4.1).

• Loss of soil fertility from excess erosion under the following situations:

– When eroded soil is fertile: Upslope farmers are negatively affected by loss of fertile topsoil, while downslope farmers benefit from the deposition of this same soil on their land.

– When eroded soil is infertile: Downslope and valley bottoms are negatively affected by deposition of infertile soil over their more fertile soil, while upslope farmers are losing only infertile soil and are less affected compared to downslope farmers (Figure 4.1).

– Irrespective of the fertility of eroded soil: Households with steep slopes are more affected by soil fertility lost to erosion than households with flatter land.

(ii) Land-use practices of some households (interest group 1) have a negative effect on other households (interest group 2). Examples include the following, which are common to most AHI sites:

• Fast-growing trees (most notably, eucalypts) planted on farm boundaries, which have a negative effect on adjacent farmers’ fields owing to competition for nutrients, water and light, and to allelopathic effects.

• Spring degradation from land-use practices of landowners with springs on or near their land, owing to the cultivation of “thirsty” trees (which tend to grow better with improved water uptake), and to the loss of protective vegetation and contamination associated with the cultivation of crops up to the edge of springs (where land owners gain from bringing a larger land area under cultivation) (see Plates 12 and 13).

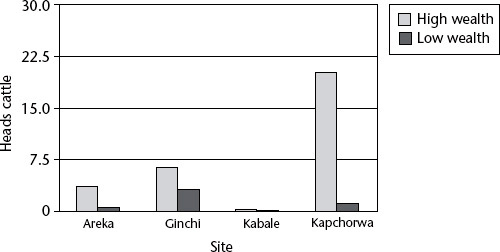

• Crop loss from free grazing, where households have very divergent livestock holdings and incentives to reduce free grazing only exist among households with low livestock endowments or deriving significant benefits from livestock sharing arrangements (Figure 4.2).

In the text that follows, AHI efforts to develop and test approaches for improving landscape governance—with an aim of enhancing both equity and sustainability—are described. The text is organized according to key methodological innovations that were tested for this purpose, including approaches for supporting negotiations among local stakeholders with particular interests vis-à-vis the identified natural resource management challenges; methods for catalyzing collective action; and methods for participatory by-law reforms. Negotiation support was applied independently of the scenario under consideration (inadequate collective action, or divergent interests). The last two approaches, however, were explicitly targeted to consider the unique features of the issues being addressed. Strategies to mobilize collective action were applied largely to problems defined by Scenario 1, while participatory by-law reforms were applied largely to problems defined by Scenario 2. The reason for this differentiation is that formally endorsed by-laws are generally required to ensure negotiated agreements are implemented in practice, given the divergent interests characterizing the latter set of issues.

FIGURE 4.1 Perceived causal linkage between soil erosion on the hillsides and soil fertility in the valley bottoms, Lushoto, Tanzania

Note: Data collected through semi-formal interviews with elders (to identify key changes in livelihoods and NRM), interpretation of reasons behind these trends (to identify causal processes and relationships among variables), and participatory ranking of rates of change in variables selected to represent observed trends.

FIGURE 4.2 Livestock holdings by wealth category in four AHI benchmark sites

Negotiation support

The first strategy tested by AHI to address landscape governance challenges (insufficient collective action or divergent interests) was to support negotiations among affected parties. This helped to raise awareness of the need to act collectively, to reconcile latent conflicts among divergent local interest groups, and to devise strategies to hold external agencies (i.e., local government, extension, conservation agencies) accountable to locally felt needs. In AHI, several broad negotiation support strategies may be distilled, based both on the level at which negotiation support was carried out and the extent to which stakeholder interests are aligned or divergent. Strategies which may be defined by the level of intervention include support to negotiations among local stakeholders within the watershed area itself on the one hand, and support to negotiations between local communities and external stakeholders on the other. The second set of strategies may be differentiated according to whether the problem affects all stakeholders equally (and thus requires simple resolution of differences of opinion on whether and how to address it), or involves divergent interests and “stakes” (and thus interests which may be advanced or undermined through the negotiation process).

Approach development

Irrespective of the nature of the issue, the negotiation support strategy employed started with the following two steps:

1. Identification of specific landscape niches where the watershed problem is manifest.

2. Stakeholder identification, to explore which of the following scenarios the problem may be best characterized by:

• Scenario 1—Different households are equally affected by the problem, but the collective action required to effectively address the problem is lacking;

• Scenario 2—Different households are negatively affected by the problem but by different degrees—thereby causing them to have different levels of motivation for investing in a collective solution; or

• Scenario 3—The issue may be characterized by two distinct interest groups, those perceived to be causing the problem and those affected by it.

At this point, once it is clear whether the problem is characterized by stakeholder groups with divergent interests, the approach diverges. If there is no such differentiation, one proceeds with the “undifferentiated” approach; if stakeholders with divergent interests are identified (Scenarios 2 and 3), one proceeds with the second approach—negotiation support involving stakeholders with divergent interests.

Approach 1—“Undifferentiated” negotiation support

If the problem is characterized by Scenario 1, the undifferentiated approach follows in which the following steps are followed with all involved parties present:

1. Provide feedback to participants on the steps taken so far and their outcomes (e.g., problem diagnosis, niche and stakeholder identification), and solicit reactions to the same.

2. Facilitate a discussion of the role of collective action in addressing the identified issue—confirming whether it is needed and why, discussing why it has been ineffective to date (or might have been more effective in the past), and agreeing on implications for the way forward.

3. Negotiate solutions that are acceptable to all parties present and implicated in one way or another by the proposed action.

4. Develop a detailed implementation plan with responsibilities and timeline.

5. Participatory monitoring and evaluation, and adjustment of work plans to address problems that arise during implementation.

As collective action involves a trial-and-error process that may not be effective the first time around, regular participatory monitoring and evaluation are required to identify deficiencies in collective action and solutions for overcoming these. The monitoring may reduce in frequency as participants become increasingly adept at working together towards a solution, but only stops once the underlying problem is solved.

Approach 2—Negotiation support involving stakeholders with divergent interests (“multi-stakeholder” negotiations)

If the problem is characterized by Scenarios 2 (households affected by different degrees) or 3 (losers and winners), the second approach is followed—which makes an explicit attempt to reconcile the interests and perspectives of different stakeholders. This approach aligns with the “stakeholder-based planning” approach described in the participatory diagnosis and planning section of Chapter 3. Following the two initial steps described above, it proceeds as follows:

1. Identification of appropriate mediators. Prior to the negotiation, an appropriate mediator should be identified—particularly for the more entrenched conflicts for which one or more parties are reluctant to enter into dialogue. This person should be someone well known and respected by both parties, knowledgeable about the technical and social aspects of the conflict, and neutral with regard to the outcome and the interests of each party. If the issue is not overly polarized, this facilitator could include project personnel, but more often local elders and opinion leaders, local administrative leaders, or spiritual leaders can be engaged as mediators, with support from project personnel.1

2. Consultation of individual stakeholder groups to identify their perceptions on the causes and consequences of the issue, possible opportunities for “win–win” solutions and approaches they are comfortable with for entering into dialogue with the other stakeholder group. These consultations also help to demonstrate the external party's concern for their “stakes” in the issue, and to reduce their fear of engagement (for fear of what they might lose). In cases of entrenched conflict or highly divergent interests, this step is often essential in bringing the two parties closer to dialogue and may involve a series of meetings (Box 4.5).

BOX 4.5 CASE STUDY ON CONFLICT: THE ROLE OF SEQUENTIAL NEGOTIATIONS

Farmers ranked spring degradation as the top watershed issue in Lushoto. Springs are communally owned according to national laws, even when located in people's fields or plots. However, individuals refused to abide by by-laws aimed to conserve the resource. Dialogue between spring owners and users was therefore necessary to avert conflict and address the problem. A series of multi-stakeholder dialogues were convened by AHI, bringing the negatively affected spring users and the landowners together to discuss how costs and benefits are distributed among local interest groups. While losses were occurring to both groups (through reduced access to water by spring users, and latent conflict for spring owners), benefits were only accruing to spring owners (e.g., from the expansion of cropping area or rapid growth of woodlots in the presence of water). Solutions were needed that acknowledged the stakes involved for both parties. In most such meetings, participants were able to agree and strike an acceptable balance. However, certain spring owners were initially reluctant to change, and often missed such meetings altogether. More targeted follow-up negotiations between local leaders and land users were effective in encouraging most of these landowners to protect the springs falling within their land. The few individuals who continued to protest—and even destroy investments made in spring protection by other community members—were eventually taken to court. Informal negotiations should be seen as complementary to formal law enforcement, given the ability of the former approach to avert longstanding conflict between families. The latter is, however, needed in some cases.

In the case of informal consultation of specific interest groups, it is also necessary to show compassion or empathy for the interests and concerns of each party. If the mediator is perceived at this time as being biased toward one party or having an interest in a particular outcome, it will jeopardize their ability to bring the two parties to the negotiating table. This should also include joint formulation of the agenda to be followed during the first negotiation, which will help diffuse tension and create a more comfortable and harmonious atmosphere for dialogue. Even the language that is used has a crucial role in either further polarizing the two parties or bringing them closer to the negotiating table at this time (Box 4.6).

BOX 4.6 PRINCIPLES OF MULTI-STAKEHOLDER NEGOTIATION: THE CASE OF THE SAKHARANI MISSION

The Sakharani Mission boundary case study described above illustrates some additional principles in multi-stakeholder negotiation. These include the following:

• Showing empathy. Having diagnosed watershed problems through the minds of farmers alone during the watershed exploration phase in effect marginalized a host of issues faced by Sakharani in relation to neighboring villages. These issues—including deforestation and its perceived effect on rainfall and water supply, and damage caused to tree seedlings from free grazing by neighboring farmers—were promptly brought to our attention in the first meeting (stakeholder consultation). By expressing empathy and concern for these problems in addition to those raised by neighboring smallholders, the farm manager perceived AHI to be a neutral and unbiased party and became more open to engaging in a negotiation process—as it was seen as a potential opportunity for addressing longstanding concerns of the Mission as well.

• Use of language. During our preliminary meeting with the Sakharani farm manager, one of the team members introduced the problem voiced by farmers—namely the negative impact of Sakharani boundary trees on neighboring cropland and springs. Use of language that unnecessarily polarized the interests of the two parties (“stakeholder”) and presupposed compromise on behalf of the landowner (“negotiation”) provoked an understandably defensive reaction in the mind of the farm manager. Careful choice of words to avoid further polarizing the issue is essential in early stages of stakeholder consultation and negotiation support. Words such as “party” and “dialogue,” for example, are less threatening than words such as “stakeholder” and “negotiation.”

• Importance of balanced concessions. The last principle relates to the first, in that deadlocks to constructive engagement can rarely be solved without each party “giving up” something for the collective good. In this case, the Sakharani farm manager agreed to change the boundary tree species from eucalyptus spp. to Mtalawanda (Markhamia obtusifolia), provided neighboring farmers kept their livestock from grazing within Mission boundaries and they both agreed to work together to recuperate degraded waterways.

3. Facilitation of multi-stakeholder dialogue between the two parties, through the following steps:

• Provide feedback to participants on steps taken so far and their outcomes.

• Jointly establish ground rules for dialogue, such as being respectful in listening fully to others and focusing on needs and interests rather than specific solutions when each stakeholder presents their perspective on the issue.

• Ask each interest group to express their views using the ground rules.

• Support the negotiation of socially optimal solutions that meet the needs of each stakeholder group and that do not overly burden households who have little to benefit from the outcome.

• Formulate by-laws to support the agreements reached by the negotiating parties (see below and Chapter 5 for additional details).

• Develop a detailed implementation plan stating what is to be done (activities), who is to do it (responsibilities), when (timeline), where (in which particular areas), and how (Box 4.7). Written agreements with the signature of all participating parties bring greater legitimacy to agreements and ensure accountability by each party.

4. Formal endorsement of by-laws.

5. Participatory monitoring and evaluation, and adjustment of work plans to address problems that arise during implementation

BOX 4.7 THE IMPORTANCE OF DETAILED PLANNING FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AGREEMENTS

Two cases illustrate the fundamental importance of detailed planning during multi-stakeholder negotiations.

Case 1—Sakharani boundary

Participants to the Sakharani boundary negotiations agreed on the criteria to be used for selecting priority areas for replacing eucalyptus with Markhamia species. However, the identification of specific boundary areas meeting those criteria was not done, leaving the most urgent case (where a neighboring farmer's home was at greatest risk of being destroyed from tree fall) unaddressed. Furthermore, the schedule of eucalyptus tree replacement was not specified, causing subsequent misunderstandings owing to divergent (unspoken) expectations. Therefore, the early trees to be removed were removed in areas of little consequence to adjacent landowners and subsequent actions were slow to materialize, undermining the spirit of agreements reached.

Case 2—Ameya spring

In the case of Ameya spring (Ginchi benchmark site), the landowner agreed during negotiations to remove eucalypts around the spring as long as other households contribute seedlings for re-establishment of the woodlot in other areas of his farm. Other details were left open. Thus the “who” was identified, but not the when, where, and how. A section of the woodlot was subsequently cut down as an expression of compliance on the part of the landowner, but the trees were not uprooted (enabling them to coppice and re-grow) and the other households did not contribute seedlings as agreed. While negotiations were ongoing at the time of writing, it is therefore clear that important opportunities are lost if concrete action plans are not developed in the first multi-stakeholder dialogue.

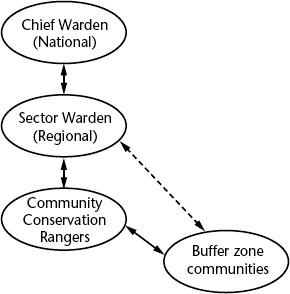

It is worth taking some time to reflect on individual steps in this process in greater depth. Before initiating negotiations, in addition to identifying different stakeholder groups in their aggregate it is important to identify the appropriate avenues and levels of decision-making for each stakeholder. These authority figures can be brought directly into the negotiation process, or can be regularly updated as the dialogue progresses so as to give their blessing to the resolutions and to keep them informed. Whether or not local leaders are directly involved in the particular conflict or niche in question, for example, they should generally be present at the negotiations or be kept informed to lend legitimacy to the dialogue and help align their actions with the process and its aims. Formal institutions involved as a party to negotiations may also have established hierarchies. In Lushoto, for example, failure to involve authorities higher up in the Benedictine Order undermined the ability of the Sakharani Mission farm manager to follow through with some of his commitments on boundary management. Had the appropriate authorities been engaged in the first negotiation process, this problem could have been avoided. In the case of co-management of the Mount Elgon buffer zone (Kapchorwa site), efforts to circumvent standard communication pathways (solid lines in Figure 4.3) by taking community concerns directly to the Sector Warden helped to move beyond conflict to reconciliation, as corrupt local level officials (rangers) had more to lose from reconciliation than higher level officials.

FIGURE 4.3 UWA communication and decision-making channels on co-management

It is also important to acknowledge the legitimate rights and authorities of each party under the law. For example, the landowner (with title or usufruct rights) may have greater authority over the use of his/her land than the affected party, as in the case of trees planted just inside farm boundaries. These rights must be acknowledged in the way the dialogue is mediated. Language matters here. For example, it is better to say to the landowner, “are there any alternative tree species that also meet your needs but minimize any negative effect on your neighbors?” than to ask the neighbors what tree species should be grown on another person's property. Similarly, supporting negotiations among parties with unequal power and authority may require a complex balancing act to acknowledge established hierarchies while also pursuing more balanced or equitable outcomes (Box 4.8).

BOX 4.8 NEGOTIATION SUPPORT IN THE BAGA FOREST BOUNDARY: MANAGING DELICATE POWER DYNAMICS

Tanzania has had a co-management policy since the late 1990s. However, these policies have yet to be operationalized in many parts of the country. In the watershed site, farmers complained that the eucalyptus—planted by the forest department to secure the forest boundary—was competing with cropland and reducing yields and contributing to the drying of springs. The site team brought the District Forestry Officer together with farmers to negotiate alternatives to current boundary management practices under the co-management umbrella.

At one point in the negotiations, the forest officer became visibly uncomfortable with the process being led by the external facilitator, as it departed from the standard approach used by the forestry department. Sensing we were losing one stakeholder's buy-in to the negotiation process, we quickly decided to hand over the facilitation role to the officer. This quickly brought him back to the table, but also tended to put much decision-making authority in the hands of only one party. Fearing we might in turn lose the community's commitment to negotiation, the team continued to play a guiding role in the negotiations, for example by pressuring the forest officer to commit to concrete deadlines for following through with agreed resolutions.

A number of additional observations may be made about the negotiation process itself. First, it is important to give each party an opportunity to express their respective views. Ground rules, such as “listening to the perspectives of others before intervening,” can be either established openly through a facilitated dialogue or integrated into the process implicitly through a skilled facilitator. For example, if one party attacks the other when expressing his or her concerns and views, the facilitator needs to intervene and impress upon people the need to fully hear out the other party and acknowledge the legitimacy of one another's concerns.

It is also important to identify solutions that can ensure the interests of both parties are met. Such opportunities can be identified through detailed exploration of the main interests of each party, to see how they might come together to resolve the concerns not of one party but of both. While the benefit of reduced conflict with one's neighbors may in some cases serve as an important factor motivating the acceptance of solutions that are otherwise undesirable, strong economic rationales often underlie the more intractable problems—requiring a solution that addresses these constraints. Effective strategies can therefore involve efforts to minimize the cost or increase the benefits associated with alternatives (German et al., 2009). And while some solutions may take the form of “win–win” outcomes, the majority will involve balanced concessions from each party (Box 4.6). Ideally in such situations, each party concedes something while also securing certain benefits. Yet parties to a negotiation will seldom offer a concession for nothing; there is often need for reciprocity in such concessions to enable a “middle ground” to be met. This is more easily done through an emphasis on “bottom lines” than by trying to ensure that each and every concern of each party is adequately met. “Bottom lines” emphasize the basic interests that must be met for each party to continue participating in the dialogue (Box 4.9).

BOX 4.9 ENSURING THAT “BOTTOM LINES” ARE MET TO SUSTAIN STAKEHOLDER COMMITMENT TO A NEGOTIATION PROCESS

Case 1—Meeting the Uganda Wildlife Authority's bottom line of biodiversity conservation

The Mount Elgon co-management case study can help to illustrate how ensuring the “bottom lines” of certain stakeholder groups can help to keep the negotiating parties committed to dialogue. Co-management was undergoing implementation in other parts of Mt. Elgon National Park, but had thus far excluded the Benet owing to the history of conflict and the perception that the Benet were fundamentally against biodiversity conservation. Identification of this bottom line of UWA helped to keep them committed to dialogue and to advance the reconciliation process. This went a long way in fostering dialogue and a commitment to shared custodianship of the Park's resources.

Case 2—Meeting landowners’ bottom line of livelihood security in spring negotiations

In the case of Ameya spring (Ginchi site), the landowner was strongly reluctant to enter into dialogue owing to his fear that he would lose a substantial investment and “safety net” if forced to remove his eucalyptus woodlot from the spring. Only when local elders expressed support for his interests did he agree to come to the negotiation table. Once there, only when the community agreed to meet his demand of bearing the costs of relocating his woodlot to another part of his farm would he agree to remove any trees from the existing location.

Resolutions reached through multi-stakeholder dialogue will also require frequent follow-up, particularly in early stages, to ensure effective implementation. When this is not done, stakeholders often identify opportunities to further their interests outside the scope of the agreement. This may be done either by failing to implement resolutions perceived to be less than beneficial to their interests, or by placing more conditionalities on their continuing cooperation than they earlier articulated to exploit gaps in the implementation plan. For example, the Ameya spring owner raised many new demands following failure of the initial agreement to specify the details of implementation. While the initial demand included only contributions of single seedlings per household, subsequent demands included community contributions to land preparation, transplanting, and fencing of the new woodlots. Furthermore, he specified that the uprooting of eucalyptus would be gradual over time, in accordance with the rate of biomass accumulation in the new woodlot. These new demands, if not covered in the original dialogue, can further polarize the issue in the minds of the other party—who by now perceives the relationship as one of exploitation rather than collaboration. Formulation of by-laws to enforce resolutions reached in early negotiations is often necessary to ensure that each party follows through with what is agreed. These proposed by-laws must often be endorsed officially by the relevant local government authorities to be effective, as described in the next section.

Finally, challenges often arise in implementing agreements owing to interactions between watershed and non-watershed communities. Two scenarios where this has occurred may be identified. In the first, parties not directly involved in the negotiations may influence the ability to effectively implement agreements. For example, non-watershed residents whose livestock freely graze in the Ginchi site during the dry season will create a burden on the efforts to police conservation structures. This was found to be particularly true in Tiro village, where the main road passes, thus concentrating livestock movement in adjacent farmers’ fields. In the second scenario, farmers residing outside pilot villages feel resentment from being excluded from highly beneficial activities such as spring development or high-value enterprises. Such was the Ginchi case highlighted in Chapter 3, where the PA leader residing outside the watershed sabotaged village meetings by calling mandatory meetings at PA level during days when watershed activities were planned. This problem was addressed by involving him in his official capacity, thereby giving recognition to his importance in addressing problems within the watershed. This has been effective in dissipating the tension between watershed and non-watershed residents. It is therefore important to either ensure all relevant decision-makers are brought on board, or—should the problems persist—to consider ways to expand some of the benefits beyond watershed boundaries.

A strategy unique to Ethiopian sites has combined sensitization with persuasion to deal with certain problems that have persisted for long periods of time. This strategy entailed regular meetings with the concerned parties at diverse levels (Woreda, PA, sub-PA, watershed, village, and individual households) to raise awareness on the issues emerging from the communities themselves and to try to bolster commitments to collective efforts to solve a particular problem. This strategy has been necessary in several specific cases, namely soil and water conservation in Areka and Ginchi (to mobilize greater participation); eucalyptus management in Areka (to reconcile divergent interests); and outfield intensification in Ginchi (to progressively engage wider sets of stakeholders). In the case of soil and water conservation in Ginchi, this strategy has also been necessary to enable landowners to agree to collective drainage canals to pass through their farms, formerly resisted owing to the space it occupies and the potential for crops to be destroyed from channeling greater volumes of water through their fields. In some sites, by-laws were formulated to help consolidate agreements reached through informal means, which has helped to ensure individuals abide by established agreements.

The approach is, however, limited in addressing problems with highly divergent interests. It was ineffective in addressing the problem of eucalyptus on farm boundaries in Areka and springs in both Areka and Ginchi, owing to the cost (of both eucalyptus removal and foregone revenue streams). Landowners therefore actively resisted change. This resistance is actually backed up by national laws mandating that a landowner must be duly compensated for any loss of property. The only viable solution in this case would be for an external actor to bear the cost of woodlot removal (given the prohibitive cost of payment in cash), or for local communities to repay the farmer in kind (e.g., through contributions to moving woodlots to new locations). In Ginchi, the approach was effective in enabling early agreements on approaches to outfield intensification, but these agreements were not ambitious enough to actually solve the problem. For example, agreements did not involve curtailing free movement of livestock in locations where trees and structures were being established, but rather the active policing of outfield areas from livestock damage. The high cost of this activity to households meant that policing was ineffective in practice and most seedlings were damaged through livestock trampling or browsing. Reluctance to engage in more far-reaching innovations was likely due to the tenure insecurity in outfields as well as the open access nature of dry season free grazing, where the users are not well defined—complicating efforts to agree on collective rules for curtailing grazing.

Lessons learned

The following lessons may be distilled from the negotiation support experiences of AHI:

• It is critical to “get it right” the first time, to avoid the additional burdens inherent in follow-up negotiations.

• Effective negotiations require detailed action plans on how to implement resolutions (specifying what, who, where, when, and how), and in cases of divergent interests, ensuring sufficient weight is given to agreements through signed documents, close follow-up and the formulation and endorsement of formal by-laws. Signed documents can assist in making proper follow-up to agreements and minimize the emergence of new demands from both parties.

• For successful negotiations, it is important to identify and involve the appropriate actors throughout the process, including both mediators and stakeholders.

• Negotiation support is the only approach used by AHI that has enabled identification of solutions that effectively reconcile the interests of two divergent interest groups, as it fosters mutual understanding and concessions for the sake of the collective good. Generic watershed planning processes are generally ineffective in this regard, leaving contentious issues unaddressed.

Mobilizing collective action for common NRM problems

Some NRM problems that require collective action to be effectively addressed but do not involve divergent interests require simply mobilizing groups of people to work toward common goals that cannot be achieved through individual efforts. There is no single approach used for this, but rather a sub-set of approaches that differ slightly in their steps and aims.

Approach development

Approach 1—Working through local institutions effective in mass mobilization

The first approach consisted of the identification of local institutions known by local residents to be effective in mass mobilization, and facilitating their efforts to call people to action around a locally identified concern. It consisted of the following steps:

1. R&D team assists local residents to identify NRM issues of high priority through a watershed exploration exercise or stakeholder meetings.

2. R&D team facilitates a process whereby watershed residents identify local forms of collective action (CA) most effective for mass mobilization.

3. R&D team members and/or expert farmers train leaders (from identified forms of CA) on technical aspects of addressing identified NRM problems (based on scientific or local knowledge or both).

4. R&D team or other chosen party facilitates agreement on the roles of identified CA institutions in mobilizing the community around shared concerns (e.g., using megaphones or traditional methods of calling the community to action).

5. Set specific days convenient for all for mass mobilization initiatives.

The approach was very effective in mobilizing collective action at a large scale owing to the involvement of multiple collective action structures, each one operating in a small area and with few households but together covering a large area. If these local institutions of collective action also have the mandate to develop and enforce by-laws, they can be even more effective in mobilizing collective efforts (Box 4.10).

BOX 4.10 MOBILIZING COLLECTIVE ACTION FOR COMMON NRM PROBLEMS: THE PORCUPINE CASE

This box describes in detail how the challenges described in Box 4.1 related to crop damage from porcupine were addressed in practice. As mentioned previously, porcupines travel long distances at night, resulting in very low returns on control efforts applied by individual households. To mobilize collective action over a wide area, individuals or groups effective in mobilizing the community and highly respected by all are needed. Farmers were therefore asked to identify an individual or entity that could be effective in this regard. Farmers selected the “developmental unit” (DU) (local administrative units consisting of 25–30 households) as a local institution most capable of mobilizing farmers. In addition to the DU being of manageable size, DU leaders were thought to be capable of enforcing local by-laws developed for this purpose and effectively monitoring implementation.

Approaches

By-laws specifying contributions to be made by each household to porcupine control were developed and approved by local leaders. Local knowledge on porcupine control was studied, and control methods appropriate to different landscape niches were agreed upon. The DU leader coordinated the mass mobilization and each family in the DU agreed to devote one or two “development days” per week for collective control efforts. DU leaders then mobilized farmers on the designated development day using megaphones and a local instrument called a tirumba and farmers applied the agreed-upon control methods for the relevant niches.

Outcomes and lessons learned

Nearly 1,000 porcupines were captured or killed in the peak porcupine season through these collective efforts. Farmers selected DUs to enable implementation owing to its proximity to communities (small administrative units with few households) and the ease with which they can closely monitor activities in their area. Development of by-laws also enabled farmers to negotiate and clarify ahead of time who would be responsible for what activities, and to ensure those agreements were respected.

Approach 2—Working with self-mobilized local institutions

The second approach seeks to capitalize upon and support self-mobilized local institutions in supporting the evolution of stronger institutions of collective action in support of NRM. This approach consisted of the following steps:

1. Community members organize spontaneously around shared NRM concerns.

2. External development actors (NGOs, research, local government) identify existing “nodes” of collective action to support, and facilitate the formation of a higher-level watershed committee.

3. External facilitators encourage newly formed watershed committee to create awareness among CBOs, NGOs, and local government on the need to collectively address the issue(s) of concern.

4. Local CA institutions conduct village-level planning, and express demand for support from external development actors.

5. External development actors call sub-county and district-level planning meeting to articulate the roles of different actors in addressing local level concerns.

This approach to community mobilization was highly effective as it was grounded in emerging forms of self-mobilized collective action and systematic efforts to provide external support to these emerging initiatives. It further catalyzed interest in new forms of collective action as a result of its effectiveness in addressing the issue and bolstering support from outside development agents or service providers.

Approach 3—Mobilizing CA through local government and NRM champions

The third and last approach consisted in the identification of existing NRM champions and supporting their efforts to mobilize complementary interventions by local government and watershed residents. Basic steps in this approach include the following:

1. External R&D team assists local residents to identify NRM issues of high priority through watershed exploration or stakeholder meetings.

2. Local NRM structures are formed (by election) or strengthened (where existing NRM and leadership structures exist) to spearhead solutions to issues identified in Step 1.

3. Local NRM structures drive a process involving local government to address shared NRM concerns (Box 4.11).

BOX 4.11 VARIATIONS ON THE APPROACH FOR MOBILIZING COLLECTIVE ACTION THROUGH LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND NRM COMMITTEES

Case 1—Controlling run-off in Kabale

The approach utilized in Kabale began with the identification of farmers from communities observed to have “zeal” to find a way to address their own NRM problems. Second, meetings were held with sub-county stakeholders to sensitize newly elected local government representatives given the recent election, and to form sub-county NRM committees. Third, sensitization was carried out at village level by selected members of the sub-county NRM committee with the assistance of LC1 leaders, faith-based organizations, radio announcements, whistles, and word of mouth. LC1s, NRMPCs and AHI worked collaboratively from this point forward, assisting in putting checks and balances on LC1s to encourage them to respond to felt needs of the community. Villages then selected convenient days of the week to hold meetings and collective action activities to avoid clashes with other important activities (market days, hangover days, days of prayer, community development days). The mobilization concluded with action planning at sub-county and village levels, cross-site visits to observe successful strategies to control extreme run-off, and training of farmers on technologies for controlling run-off.

Case 2—Spring development in Ginchi

As already mentioned, decline in water quality was identified as a priority watershed issue in the Ginchi site. A watershed committee composed of representatives of each watershed village was formed. They called on the village-level government (Gare Misoma) to call a meeting on the need to formulate a plan for spring protection, who in turn mobilized the community. In addition to watershed residents and researchers, district-level ministries (the Bureaus of Water Resources, Health and Agriculture, and Rural Development) were called by the Gare Misoma to the meeting. A series of meetings with diverse local stakeholders was held to agree on how rights (to water use) and responsibilities (materials, labor, and cash for spring construction and maintenance) would be allocated both within the watershed and with adjacent villages. Contributions to be made from external stakeholders (funds from AHI, technical assistance from the Ministries of Water Resources and Health) were also agreed upon at this time. After the spring was constructed and officially “gifted” to the community, a Water Committee was established and trainings given on spring maintenance and governance. While spring users contribute small cash payments for maintenance, the Ministry of Water Resources retains the mandate to provide additional technical assistance as required.

This approach is highly effective because collective action was mobilized to address an acute problem facing the community. In those cases where newly formed or reconstituted NRM structures worked hand in hand with local government (spring protection in Areka and Ginchi, and run-off control in Kabale), complementary roles were played by these two institutions, further contributing to the success of mobilization efforts. Local government has a role in mobilization of development efforts in Ethiopia, as well as by-law formulation and enforcement functions in all countries. However, government actors had not adequately addressed common NRM problems owing to lack of capacity (financial, technical), greater emphasis on government-set development agendas than locally felt priorities, or local political interests (getting votes). In a study in Uganda (Sanginga, et al., 2004), ineffective by-laws were found to be the result of weak enforcement by local leaders, lack of awareness on by-laws, outdated regulations, legislative conflicts, small plot size, absence of extension facilities, and the desire to avoid confrontations within and among households and with the local leadership. Newly formed or reconstituted NRM structures emanating from the community itself therefore assumed a complementary “civil society” function of pressuring local government units to work on local NRM priorities. The downward accountability of local NRM structures combined with the authority of local government structures proved to be more effective than either actor working in isolation. In the Kabale case, additional success factors included the use of multiple strategies for mass mobilization and the network of local institutional structures (NRMPCs) to support the mobilization effort.

Lessons learned

Approaches tested for mobilizing collective action around common NRM problems have taught us that:

• Different actors (local government, community-based NRM structures, faith-based institutions, NGOs, CBOs) and strategies (radio, traditional methods, and megaphones) play complementary roles in the mobilization process. When several actors and strategies are engaged simultaneously, mobilization is likely to be more effective.

• Mobilization is easiest when building upon existing or emerging local institutions and collective action initiatives.

• Networks of local institutions are highly effective in mobilizing collective action because they combine a “personalized” approach (e.g., going door to door) with coverage of large areas (by working through multiple local institutions spread throughout the landscape).

• Early successes in mobilizing collective action around specific NRM issues can catalyze community confidence to address new challenges.

• Farmers are willing to invest in NRM on other people's land, provided that: (i) the benefits are for the majority; (ii) the problem cannot be effectively solved individually; and (iii) the gestation of benefits is short term.

Participatory by-law reforms

In addition to informal negotiation support, participatory governance was furthered through participatory by-law reform processes at village and higher levels. The process of negotiating rules and seeking their formal endorsement helped both to clarify aims among diverse parties, as well as to bolster commitment to putting into practice what was agreed upon in informal negotiations.

Three approaches are presented here. The first two, both applicable at village level, were selected based on the issue at hand and the implications for those who should be present during negotiations and/or by-law reform processes. The third approach is best differentiated from the first in its efforts to strengthen the capacity of local institutions and local government to facilitate the participatory by-law reform process, and may therefore be seen as a way to institutionalize the first two approaches.

Approach development

Approach 1—By-law reforms through village-level negotiations

The strategy used in this approach was to hold village-level meetings specifically focused on natural resource governance. While these meetings do not differentiate among local interest groups with divergent ‘stakes’ in the issue, equitable participation by gender and lower-level administrative units (i.e., hamlets in Lushoto site) must be ensured when identifying participants to be called to the meeting. Local leaders charged with proposing by-law reforms and with bylaw enforcement should also be present, to help inform and guide negotiations. These meetings employed the following steps:

1. Use of graphical representations of landscapes with and without rules governing NRM, to foster a collective understanding of the role of governance (see Plate 14).

2. Feedback of watershed problems identified by local residents.

3. Introduction of meeting objectives (namely, to identify the need for governance solutions to address identified watershed problems) and identification of types of shortcomings that might exist in policies, norms and by-laws (namely, poor enforcement, gaps in coverage for certain watershed problems, and poor design undermining its utility in addressing the problem even if enforced).

4. Identification of existing policies, the extent to which they are enforced (and enforceable under local conditions), and how effective they are in addressing identified problems when enforced.

5. Discussion of whether any new by-laws are required to address identified watershed problems, and development of revised by-laws (where existing by-laws are deficient for addressing identified watershed problems) or new bylaws (in cases where no current by-laws exist to address identified problems).

6. By-law endorsement, implementation and monitoring.

Approach 2—By-law reforms in the context of multi-stakeholder negotiations

The second approach to by-law reforms is one and the same with the approach to negotiation support described above. It differs from the first in its explicit attempt to identify and engage in negotiations groups with divergent interests, so as to overcome the impasse that tends to characterize many collective action challenges. It therefore differs by the nature of participants, with this process involving only those with personal interests or stakes in the issue at hand. It is important to note, however, that when negotiation support leads to formal by-law reforms, it will be important to find a means to “scale up” agreements to the lowest administrative level at which by-laws may be formulated. This is because once approved, by-laws apply to all residents within an area; their buy-in is therefore critical.

Approach 3—By-law reforms embedded in local government structures

The third approach to participatory by-law reforms is embedded in local government structures established under decentralization reforms, as presented in Chapter 3 (Approach 2 of participatory watershed diagnosis and planning). Here, by-law formulation is integrated into a more general strategy of working through community organizations and local government structures to support participatory INRM. In this approach, these existing structures are themselves empowered with facilitation skills to support participatory INRM and by-law reforms within their respective local administrative structures.

A comparison of the three approaches gives an idea of their relative strengths and drawbacks (Table 4.1). The unique features and purposes of the three approaches, however, suggest that with adequate funding they could be best employed in tandem—with Approach 3 used to build the capacity of local institutions and administrators to implement the specific negotiation support processes outlined in Approaches 1 and 2. A comprehensive approach for linking actors at different levels in the by-law reform process, which could serve as the backbone to the multilevel governance reform process, will be presented in Chapter 5.

It is important to reflect on the stages after negotiations are concluded. It is clear that by-law endorsement by higher-level officials is a necessary condition for their effective enforcement. Yet even with this endorsement, by-laws can be ignored. The following reasons have been identified by farmers for poor enforcement of existing or new by-laws:

• The difficulty of holding certain community members (e.g., traditional healers, wealthy farmers, relatives of the leadership) accountable to by-laws, as they are feared for their status within the community or relationship with local leaders.

• Non-compliance of certain local government leaders with by-laws, which serves as a strong deterrent to others abiding by the by-laws.

• Negative livelihood consequences of enforcement for some households (Box 4.12).

• Failure to provide livelihood alternatives for activities forbidden or curtailed through by-law enforcement (such as disseminating fodder trees in exchange for restrictions on free grazing), thus undermining enforceability.

• Failure of government officials to apply sanctions when offenders are reported, owing to corruption or favoritism.

TABLE 4.1 Comparison of approaches to participatory by-law reforms

BOX 4.12 THE LIVELIHOOD COSTS OF IMPROVED GOVERNANCE

Some by-laws proposed by community members themselves may carry detrimental effects for certain households. For example, by-laws to protect springs and waterways restrict the land area available for cultivation and grazing, in particular for those households that have springs, streams, or irrigation canals on or passing through their farms. Regulations on free grazing of livestock will have consequences on livestock productivity, in particular for households with larger livestock endowments or relying more on free than on zero grazing. By-laws regulating the distance at which certain tree species (those perceived to be overly “thirsty” or harmful to crops) may be grown relative to farm boundaries or springs restricts land-use options and revenue streams for those households practicing these activities. Governance must ultimately balance the social and environmental costs of the status quo (i.e., declining water resources, negative effects of boundary trees on neighbors, conflict) with the costs of solving these problems for the collective good. Alternative technologies (e.g., fodder, crop-compatible trees) can also go a long way in minimizing the livelihood costs of more equitable land management practices (German et al., 2009).

The livelihood costs of improved governance were a very crucial finding, suggesting there are often significant economic deterrents to more equitable, sustainable NRM. Two different possibilities exist for minimizing these costs—one technological and one social. As illustrated in Box 4.12 and in Table 4.2, technologies can play an important role in minimizing the cost of by-law enforcement to those households whose livelihood options would be curtailed in the process. It is interesting to note that during participatory by-law reform processes, complementary governance and technological solutions are almost always spontaneously proposed by participants. This has an important bearing on the sequencing of implementation. By-law formulation must come first, as new by-laws highlight technologies that may be introduced to help minimize the livelihood costs—and enhance the effectiveness—of by-law enforcement (e.g., fodder species providing a feed alternative to free grazing). Awareness of the by-law and its date of enforcement must also be effectively carried out far enough in advance of enforcement to enable households to adopt alternative practices to substitute those that will be curtailed through by-law enforcement. Only then must technologies be made available to all households, as awareness creation on upcoming by-law enforcement will affect demand for technologies and adoption levels. Finally, after livelihood alternatives are in place (i.e., fodder is now available), by-laws may begin to be enforced.

Interactions between watershed and non-watershed residents also have a bearing on effective by-law implementation. For example, a ban on free grazing in the Tuikat Watershed of Kapchorwa has been effective only in controlling free grazing by watershed residents, but not by farmers living outside the watershed. A case from Kabale also illustrates this challenge (Box 4.13).

TABLE 4.2 Proposed solutions to identified NRM problems in Ginchi benchmark site

Problem |

Technological solutions |

Governance solutions |

1. Water quantity |

(i) Spring development (ii) Physical and vegetative |

(i) By-law specifying which tree species (ii) By-laws to balance benefits with (iii) [Following negotiations at Ameya |

2. Incompatible |

(i) Substitute species for farm |

(i) Minimum 10m barrier between (ii) Payment of reparations if policy is (iii) By-law specifying acceptable |

3. Soil erosion |

(i) Technologies for erosion |

(i) Non-conserving farmers will (ii) By-laws governing drainage and |

BOX 4.13 NRM BY-LAWS SHOULD EMBODY FAIRNESS IF THEY ARE TO BE UPHELD AND WIDELY ADOPTED

In Kabale District, AHI support to the formulation of local NRM by-laws raised questions of equity, owing to the initial emphasis on implementing them only in pilot villages. The consequences of NRM by-laws applied in one area but not in others are numerous and often controversial. Villages where the by-laws do not apply regard them as “alien” or “AHI” by-laws, and often resented or worked to actively undermine them. Owing to the prevalent practice of land fragmentation—where individual households own land plots in several landscapes and administrative units (i.e., villages, parishes, and sub-counties)—residents often complained that by-laws were unfair, and hence ineffective, since they only applied in particular locations. Consequently, some farmers were disturbed by the fact that they could freely graze their livestock in some areas, but were denied the right to graze in other “AHI” areas. At times such site-specific variations in by-laws aligned with areas under different administrative units. In a bid to partially redress this inequity brought about by the uneven application of NRM by-laws, NRM Protection Committees resolved to hasten the process of lobbying and convincing the different leadership structures at sub-county level to harmonize the diverse NRM by-laws emanating from different villages, and endorse and publicize these harmonized rules.

Lessons learned

The following lessons were learned from efforts to facilitate participatory by-law reforms in AHI benchmark sites:

• Informal resolutions are generally ineffective in ensuring agreed-upon rules are respected, requiring local government involvement in by-law endorsement and enforcement.

• The importance of creating awareness of the possible benefits of improved governance of natural resources, and of existing policies and by-laws, in the process of by-law review and formulation. Graphical representations of landscapes with and without by-laws can go a long way in stimulating awareness and interest in good governance during participatory by-law reforms.

• Corruption in different levels of government is a strong determinant of poor by-law enforcement, and must be addressed in efforts to improve natural resource governance in the region. This holds from village level (largely owing to interpersonal reasons and self-interest) up to district level (owing to financial and material gain from non-enforcement). It is of fundamental importance that local government leaders govern by example, and that these local leaders be sensitized in the consequences of their actions in this regard.

• By-laws must be applied uniformly in order to avoid negative transboundary effects; local government has an essential role to play in harmonizing by-laws across villages with a high degree of interdependence in their natural resource management practices.

• There is an urgent need to integrate livelihood considerations into landscape governance efforts to enhance their social and economic feasibility. For example, those negotiated agreements that create livelihoods costs to at least one party require livelihood options to minimize those costs. These options often involve technologies that can substitute for the functions of foregone land uses (e.g., fodder in exchange for free grazing).

Missing links