6

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

AND SCALING UP

Context and rationale

Cases of participatory watershed management ... managed by NGOs, are becoming increasingly abundant. Yet, almost without exception, they are very small in scale and can be expanded only by repeating the same slow, costly, in-depth techniques in successive villages. Many government-sponsored approaches have expanded rapidly, but often lack the local ownership and group coherence necessary for sustainable management of the common pool components of watersheds. If approaches ... are to be participatory and rapidly replicable, then the preconditions for scaling up have to be identified and introduced into the design of projects and programmes.

Farrington and Lobo, 1997: 1

Over the last decade, there has been a growing concern among donors and development agencies about the limited impact that natural resource management (NRM) technologies and practices have had on the lives of poor people and their environment. Interventions have often failed to reach the poor at a scale beyond the target research sites (Ashby et al., 1999; Briggs et al., 1998; Bunch, 1999). Acknowledgment of this fact has resulted in a recent surge of interest in the concept and practicalities of “scaling up.” Yet organizations accustomed to work at a certain scale struggle with the organizational, methodological, and financial challenges of “going to scale” (Snapp and Heong, 2003). Technologies that are relatively easy to assimilate into farming systems and bring rapid returns to farmers can often spread of their own accord (Chapter 2, this volume). Yet moving beyond socio-cultural and institutional barriers to access, and disseminating more complex NRM technologies at larger scales, pose more complex challenges (Middleton et al., 2002). If technologies and novel approaches to research and development are to be rapidly replicable, then the preconditions for scaling up have to be identified and introduced into the design of projects and programmes (see, for example, Farrington and Lobo, 1997). This chapter explores AHI experiences with “scaling out” from benchmark sites and facilitating institutional reforms for more widespread impact.

Scaling out and institutional change defined

The proliferation of terminology around efforts to “go to scale” has created a lot of confusion, with the terms scaling out, scaling up, horizontal scaling up and vertical scaling up, among others, often used interchangeably. For example, for the World Bank (2003) the term scaling up is used in reference to the replication, spread, or adaptation of techniques, ideas, approaches, and concepts (the means), as well as to increased scale of impact (the ends), while for Lockwood (2004) scaling up implies expanded coverage rates to rapidly meet the needs of diverse groups or to ensure that “islands of success” are maintained at expanded scale.

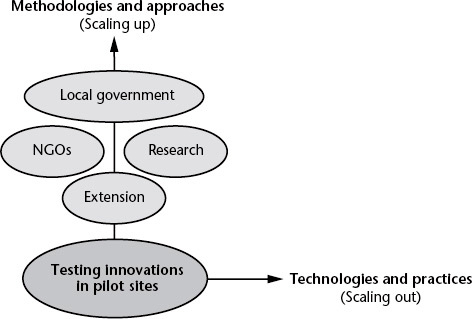

The use of different terminology to say the same thing requires that one's definitions be clarified up front. AHI adopts definitions similar to those proposed by Gündel et al. (2001), which clearly differentiate between the horizontal and vertical dimensions of “going to scale” as a question of geographical expansion vs. changes in structures, policy, and institutions. To be more precise, AHI defines “scaling out” as a process of reaching larger numbers of a target audience through expansion of activities at the same level of socio-political organization. In short, it implies doing the same things but over a larger area. “Scaling up,” on the other hand, involves innovations at a new level of socio-political organization—namely, support to institutional changes which enable tested innovations or the process of innovation itself to be supported over a larger area (Millar and Connell, 2010). In short, it involves doing new things at a level where it will make a bigger difference. It often involves taking the lessons and experiences from pilot projects to decisions that are made at the upper levels of management, such as what kind of approaches to support and where. Institutionalization is the process through which new ideas and practices become acceptable as valuable and become incorporated into normal routines and ongoing activities in society (Norman, 1991). It is a more permanent form of scaling up, as it involves assimilation of the innovation into the everyday structures, procedures or practices, or organizations. According to Jacobs (2002: 178), institutionalization is a change that has “relative endurance” or “staying power over a length of time,” or “has become part of the ongoing, everyday activities of the organization.” Figure 6.1 helps to visualize how scaling out and scaling up are conceived of within AHI.

FIGURE 6.1 Scaling out and scaling up in AHI

In the context of AHI, many activities—whether at farm, landscape, or district scale—have been designed as pilot or demonstration projects enabling the design and testing of innovations to explore “what works, where and why.” This has enabled the program to test what does or does not work well and identify needed adjustments, before engaging in costly (and risky) innovations at a broader scale. This “piloting” strategy is essential for enhancing innovation while ensuring efficient use of resources.1 It helps to avoid the traps of sticking to the status quo (which may or may not be working well) for fear of making costly mistakes and supporting costly innovations before they are proven to work. Yet it also leaves the innovation process incomplete, as the process of taking pilot experiences to a larger scale remains—and is also likely to involve further refinements for the approach to become more widely applicable to new contexts.

Methodological innovation in AHI has been structured around a set of “learning loops”—key analytical thrusts that have been the subject of action research-based learning (Figure 6.2). It is important to note that while the innermost loops are largely focused on developing novel methodological innovations, the outermost loop focuses on “going to scale.” This encompasses the dissemination of lower-level social and biophysical innovations as well as new types of institutional innovations to enable the former to be applied as part of everyday institutional practice, and to support the institutionalization of the overall approach to action research.

Before closing the section on definitions, it is important to acknowledge the partnership dimension of scaling up. To some authors (Uvin and Miller, 1994; 1996), scaling up implies increased interaction with diverse stakeholders. FARA (2006) has also emphasized the need for widening the scope of participants in agricultural research beyond traditional actors to bring impact to rural communities. This view is in tandem with proponents of the innovation systems approach (Hall, 2005; Sumberg, 2005) and beyond farmer participation (Scoones et al., 2007). While this is not an explicit feature in AHI definitions, it is explicit in the innovations tested by the program.

FIGURE 6.2 AHI “Learning loops”

Elements of “scalable” innovations

An objective of AHI is to spread successful innovations (whether new approaches to development and NRM or tangible technologies) from pilot benchmarks to new environments, be they communities or research and development organizations. Scalability may be defined as the ability to adapt an innovation to effective usage in a wide variety of contexts (Clarke et al., 2006). From both empirical work and interactions with farmers, researchers, and managers, AHI has harvested some of the elements regarded as key ingredients for innovations to be scalable in a given context (Box 6.1).

BOX 6.1 CHARACTERISTICS THAT DETERMINE THE POTENTIAL OF AN INNOVATION TO GO TO SCALE

Valued outcomes: The ability of the innovation to generate income and enhance well-being at community level or to achieve policy objectives at the institutional level. An example of the former is a high-value cash crop with a ready market in urban centers. An example of the latter is a methodological innovation within a research or development organization that promotes institutional objectives (e.g., farm-level value capture, market-oriented research), or demand-driven service provision.

Effectiveness: The ability of the innovation to meet the goals and aspirations of beneficiaries. For example, an approach or process that emphasizes equitable technology distribution or sharing among individuals and among villages will appeal to the majority of farmers, especially those with meager resources and formerly excluded by research and development programs.

Efficiency: What is being piloted is cost-effective, thus enhancing its potential for scaling up and out. Production of a unit of good or service is termed economically efficient when that unit of good or service is produced at the lowest possible cost, relative to the value it generates. With limited financial resources, this consideration is particularly important in an organization's decisions to invest in particular research or development activities.

Sustainability: The potential for the benefits from the innovation process to be enjoyed over prolonged periods by the recipients, even after those supporting its dissemination are no longer involved. This is a characteristic of a process or state that can be maintained at a certain level indefinitely. Although the term is used more in environmental circles, it is relevant to social processes (e.g., participation, collective decision-making, institutional collaboration) that work in tandem with technologies.

Yet it is not just the characteristics of the innovation that matter, but the nature of the scaling up/out process itself, that will determine its success. For scaling out to be effective, the following conditions must be met:

• The participatory process of problem identification and prioritization, and the matching of innovations to these priorities, must be effective and sustained over time.

• Efforts must be made to overcome the social and institutional constraints to spontaneous and mediated forms of technology dissemination, such as the tendency for gender-based patterns of technology access or the bias exhibited by extension agents in some countries or locations toward wealthy male farmers (who can more easily innovate).

• Adequate attention is given to developing the financial, human, and social capital required to apply the technology successfully (Adato and Meinzen-Dick, 2002; Knox McCulloch et al., 1998).

• Adequate attention is given to adapting the technology to local conditions (Chambers et al., 1989).

For scaling up to be effective, the following conditions must be met:

• Committed leadership to identify and support new strategic directions.

• Budgetary reallocations and the provision of sufficient financial resources to support proposed institutional changes.

• Behavioral and attitudinal changes that exhibit a willingness to make reforms (e.g., the decentralization of authority and resources) (Gillespie, 2004).

• Realignment of institutional incentive mechanisms such as staff performance appraisals to new policy objectives.

• Strategic networks to build upon complementary skill sets, institutional mandates, and resources.

• Scaling up fast-track interventions needs to be well aligned with government policies and procedures so as to ensure sustainability (Buse et al., 2008).

• Scaling up requires that the host organization has the capacity to interest people and enable them to adopt new ideas or diffuse the intended innovations (Senge et al., 1999).

• Ability to cope with and adapt to a diversity of contexts and dimensions that are political, institutional, financial, technical, spatial, and temporal (Gonsalves and Armonia, 2000).

Learning organizations

As part of an introduction to institutionalization, it is important to consider what is known about characteristics that make organizations effective in meeting new challenges and adapting to change. One highly relevant body of literature in this regard is that which explores the nature of “learning organizations.” Just what constitutes a learning organization is a matter of ongoing debate (Argyris and Schon, 1996; Senge, 1990). In this sub-section, we explore some of the themes that have emerged in the literature and among key thinkers on the subject.

The concept of a learning organization emerged in response to an increasingly unpredictable and dynamic business environment. Organizational learning involves individual learning, and those who make the shift from traditional thinking to the culture of a learning organization develop the ability to think critically and creatively. According to Meinzen-Dick et al.,

[this] can be fostered by a spirit of critical self-awareness among professionals and an open culture of reflective learning within organizations. In such an environment, errors and dead ends are recognized as opportunities for both individual and institutional learning that can lead to improved performance.

Meinzen-Dick et al., 2004

The term “learning organization” was coined in the 1980s to describe organizations that experimented with new ways of conducting business in order to survive in turbulent, highly competitive markets (see Argyris and Schon, 1996; Senge, 1990). The aim in such organizations is to become effective problem solvers, to experiment with new ideas and to learn from internal experiences and the best practices of others. In the learning process, positive results accrue to individuals and the organization or to the organizational culture as a whole. However, concrete cognitive (mental) and behavioral traits, as well as specific types of social interaction and the structural conditions to enhance the likelihood that the necessary organizational qualities are achieved and sustained over time, need to be in place. Some of these key qualities are communication and openness; a shared vision, open inquiry and feedback; adequate time allocation for piloting new ideas; and mutual respect and support in the event of failure. Senge (1990) notes that for learning to be effective, the personal goals of staff in such organizations must be in line with the mission of the organization.

The process of evolving into a learning organization therefore involves behavioral change, and changes in the ways of thinking and information processing (Garvin, 1993). It may take as long as five to ten years for institutional change to become part of the corporate culture, given the fragility of change and resistance that often accompanies it (Kotter, 1995). This is because most people practice defensive reasoning; because people make up organizations, those organizations also tend to exhibit this culture (Argyris, 1991). So at the same time that an individual or organization is avoiding embarrassment or the threat of failure, it is also avoiding learning. Senge et al. (1999) point out that there is also a need to focus on understanding the factors limiting change, such as lack of systems thinking, fear and anxiety in the face of change, and the danger of innovations acquiring “cult status” and thus becoming isolated from the organization. Kotter (1995) has suggested that the failure to “anchor” cultural change is a key challenge to learning organizations. Thus, until new behaviors are rooted in social norms and shared values of the organization, they are subject to resistance.

Research and development organizations also operate in a dynamic world and must learn to adjust to changes in their context in order to be effective and, often, in order to survive. The institutional learning and change (ILAC) initiative of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research represents a formalized response of the agricultural sector to embrace the concept of institutional learning.2 The ILAC mission is to strengthen the capacity of collaborative programs to promote pro-poor agricultural innovation, and to ensure that research and development activities are managed more effectively vis-à-vis contributions to poverty reduction. Institutional learning and change is a process that can change behavior and improve performance by drawing lessons from the research process and using them to improve future work. The ILAC framework encompasses a set of emerging interventions that will strengthen performance by encouraging new modes of professional behavior associated with continuous learning and change (ILAC, 2005). Research in the ILAC model involves multiple stakeholders in a process that is more participatory, iterative, interactive, reflective, and adaptive.

According to ISNAR (2004), research activities that would allow for institutional learning and change include new modes of working, such as: (i) public–private partnerships as research organizations embrace a market-led research agenda; (ii) new research approaches oriented towards innovations in the commodity value chain; and (iii) new paradigms that link research, extension, universities, and farmers’ organizations in participatory knowledge quadrangles. While R&D actors engage in these activities, institutional change and learning take place, leading to the generation of lessons that further inform thinking and organizational practice.

Institutional change in agricultural research systems

As much of AHI's work on institutional change involved national agricultural research systems (NARS), it is worth taking some time to summarize what is known to date about institutional change and innovation in these organizations.

Historical evolution of research approaches

In the past, most agricultural research and extension organizations have carried out research and extension in a top-down or linear manner. Technologies have in large part been generated on-station, with minimum inputs of end users to define desirable characteristics of the technology, and then transferred to the end users using the unidirectional “transfer-of-technology” model (research to extension to farmers) (Hagmann, 1999). This approach tends to be commodity based and employs a unidirectional communication model, undermining the extent to which the socio-economic circumstances of the end users are considered. With such an approach, R&D institutions are unable to adequately respond to the demands of end users.

Historically, the focus of research in the CGIAR and in NARS has been on food crops and on high yielding varieties. This has led to some undeniable successes, with nearly 71 percent of production growth since 1961 occurring owing to yield increases (Hall et al., 2001). However, recognition of the huge gap between what scientists do and can do on-station, and what farmers do and can do on-farm, led to a conviction that major changes were necessary in the way in which technologies were designed and evaluated (Collinson, 1999).

There is evidence from adoption studies and direct feedback from farmers that technologies developed by research were not always relevant to farmers’ needs because the socio-economic and agro-ecological circumstances of the end users were seldom considered (Baur and Kradi, 2001). Probst et al. (2003) show that the complexity and magnitude of farmers’ problems have increased considerably and “new” approaches, concepts, and theoretical perspectives are needed. They argue that research should shift from a focus on the production of scientific “goods” to support more integrated and complex livelihood options. Collinson (2001) lays the blame for low research impact among smallholder farmers in developing countries on conventional approaches and paradigms undergirding applied research institutions. He argues that in this paradigm, scientists and managers give their allegiance to commodities, disciplines, and institutions rather than to the intended beneficiaries as the appropriate drivers of research programming and organization.

In response to these critiques, research approaches have gone through a series of transformations in an attempt to enhance the effectiveness of research in achieving impact. One of the first shifts was from on-station research to on-farm research, notably through the farming systems research (FSR) approach. Even FSR has gone through a series of conceptual and methodological transformations, with its guiding conceptual framework expanding from an initial emphasis on cropping systems in the 1970s to an emphasis on farming systems in the 1980s and on watershed level work in the 1990s (Hart, 1999). Part of this transformation involved an increasing emphasis on farmer participatory research (FPR) (Ashby and Lilja, 2004; Collinson, 1999), where farmers’ circumstances and criteria become central to problem definition and research design. The move from FSR to FPR was necessitated by the tendency of researchers to lead the research process in FSR, with limited involvement of farmers. Other reasons were that: (i) smallholder farmers, particularly in marginal areas, were not benefiting from the yield increases achieved through FSR; and (ii) the commodity orientation, which places emphasis on finding the best germplasm and the best husbandry to maximize yields, isolates results from the everyday realities of farmers (Collinson, 1999). The shift to FPR, where effectively applied, led to the more active participation of farmers in decision-making at all stages of research, from problem identification to experimentation and implementation, and even the dissemination of research results.

While these approaches led to important changes in research methodology and involvement of smallholders, they failed to catalyze large-scale impacts from agricultural research and extension or widespread changes in institutional practice. The demand for demonstrable impacts of research and development efforts is now high on the agenda of governments, donors, and civil society (FARA, 2005; IAC, 2004; NEPAD, 2001; Williamson, 2000). In this regard, national agricultural research organizations in developing countries are seeking ways of improving the involvement of stakeholders in research and development (R&D) processes to achieve greater impact and more efficient research systems in times of shrinking budgets (AHI, 2001, 2002; ASARECA, 1997). This has led to a drive for institutional change throughout the system.

New drive for institutional change

The demand for demonstrable impacts on poverty has led to a call for institutional learning and change (ILAC) within the agricultural profession and institutions (Ashby, 2003; Meinzen-Dick et al., 2004; Okali et al., 1994). A number of initiatives have supported institutional change in the agricultural sector in Africa and beyond. One of the most prominent is the World Bank's efforts to work with developing countries to improve the ability of their national agricultural research organizations (NAROs) to generate technology that increases agricultural productivity while alleviating poverty (World Bank, 1998). In so doing, diverse reforms have been carried out in an effort to make research systems more effective.3 These have included efforts to: (i) ensure greater administrative flexibility to enable the pursuit of financing from diverse sources, guarantee timely disbursement of funds and provide a system of open and merit-based recruitment, pay, and promotion; and (ii) deepen the involvement of different stakeholders (farmers and others) to help focus research on client needs. Interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approaches have been promoted as part of the latter effort (and adopted with varying degrees of success) and as a means to accommodate the diversity of farmers’ needs, integrate production with the management of natural resources that sustain agricultural productivity, and ensure contextual factors (constraints and opportunities beyond local control) are considered.

More recent efforts such as Integrated Agricultural Research for Development (IAR4D) and innovation systems approaches recognize the need to extend beyond technological innovation to cover a wider set of institutional and policy innovations essential for rural development. Such developments must be multi-directional, expanding the institutional knowledge base of research institutions to enhance the contribution of research to agricultural innovation, while also enhancing the capacity of individuals, organizations, and innovation systems to catalyze this innovation and better articulate the contribution of research to it (ISNAR, 2004). ICRA-NATURA (2003) further argues that capacity building in key components of IAR4D is essential for bringing about the desired impacts from research investments. This is because the shift from the traditional commodity-based and disciplinary approach to more integrated approaches will expand the complexity of challenges faced, and thus the knowledge systems and skill sets required to confront these. It is also important to recognize that change will only be meaningful and sustained when there is buy-in from within organizations. When involving institutional leaders themselves in institutional learning and change, change objectives can emerge from within—shaping the nature of institutional aims and the strategies seen as most likely to support these.

In support of this call for institutional reforms in agricultural research, AHI has worked with NARS to support institutional learning and change using an action research/action learning approach. The approach aimed to ensure that institutional change objectives and processes within national research systems respond to the concerns of managers and national policy priorities, as well as the needs and interests of the intended beneficiaries. The challenges facing AHI and its NARS partners included: (i) how to build in-house capacity for critical reflection and experiential learning at institutional level; and (ii) how to form strategic partnerships with organizations beyond agricultural extension.

The sections which follow highlight approaches taken to scale out proven innovations from benchmark sites and for supporting institutional change, and lessons learned in the process.

Scaling out proven innovations from benchmark sites

As illustrated in Chapters 1 through 5, AHI places an emphasis on action research for the purpose of developing and testing innovative approaches to INRM. This requires sustained investment by donors and site teams in specific locations (plots, farms, villages, micro-watersheds, and even districts) in a process of experiential learning and trial and error. Thus, activities are implemented as pilot or demonstration projects to test what is and is not working and undertake any needed adjustments, before translating lessons from benchmark or pilot sites to a broader scale. Once specific solutions or approaches to generating these are validated in benchmark sites, R&D teams face the challenge of scaling these out to wider areas. The overall goal of scaling out is to reach more people with technologies, approaches, and tools that have been validated in pilot learning sites and thus expand impacts on livelihoods and landscapes.

Lessons learned from the original testing of methods and approaches in benchmark sites are key ingredients to scaling out to new farms, villages, watersheds, or districts. However, scaling out is also in and of itself a learning process, owing both to the process of discriminating among past interventions to highlight those that worked the best and to the surprises that come from implementing a similar set of actions in new locations. The process also requires some methodological innovations, as scaling out implies using new techniques or approaches to spread the same innovations but over a wider area.

Approach development

Two primary approaches were tested for scaling out successful innovations from AHI benchmark sites.

Approach 1—Implement a high-profile activity and advertise it well

One approach that was tested involved few steps, as follows:

1. Replicate the successful activity in a highly visible location that is accessible to a large number of people;

2. Publicize the activity, approach used, and impacts obtained using mass media; and

3. Find means to effectively harvest expressions of interest in adopting the approach, and support endogenous efforts to learn from project experiences.

A notable example of this approach is the water source rehabilitation activities carried out in Lushoto, Tanzania. It is worth noting that AHI research teams in the benchmark sites not only considered and dealt with agricultural technologies and approaches, but also ecosystem services that were seen as central to community livelihoods. The idea was not only to build rapport with the community based on the program's responsiveness to NRM priorities highlighted in the participatory diagnostic exercises (thus hoping to catalyze interest in a wider set of activities), but also to link water source improvement to broader processes of INRM at landscape level (e.g., reduced erosion, labor saving for investment in other NRM activities, etc.).

Approach 2—Document successes and demonstrate them to the target audience

A second approach has been to monitor implementation of the innovation and gather proof of its effectiveness, and to host targeted dissemination activities. The following generic steps were taken to scale out integrated solutions to new watersheds or districts:

1. Ensure the development and documentation of successful innovations in pilot sites by following a minimum set of necessary steps:

a) Facilitate a participatory process of problem identification and prioritization, planning, and implementation for the most pressing concerns related to agriculture and NRM, as described in Chapters 2 through 5;

b) Provide close follow-up to implementation through periodic monitoring and reflection meetings with intended beneficiaries, to ensure any emerging problems are rapidly addressed. This enables adjustment and replanning as needed, while identifying, addressing, and documenting success factors and challenges; and

c) Evaluate the effectiveness of the approach using participatory monitoring and evaluation or measurement of project-level indicators through a more formal impact assessment.

2. Host an event to showcase successful innovations to relevant stakeholders and decision-makers to stimulate demand and bring pride to communities hosting the innovation.

3. Provide follow-up to organizations interested in scaling out the approach to their respective areas of operation.

Field days with diverse stakeholders have been widely used by AHI as mechanisms for scaling out successful technologies and approaches. This is an opportunity for participating farmers to demonstrate and testify to the performance of the technology or approach to non-participating farmers, policy and decision-makers, input suppliers, NGOs, CBOs, and other relevant stakeholders. Box 6.2 illustrates how such a field day is carried out through a case study from Areka BMS in 2007.

BOX 6.2 FIELD DAY IN AREKA, SOUTHERN ETHIOPIA

Phase III of AHI at the Areka BMS started with a participatory exploration of problems of Gununo watershed, in 2002/2003. Problems were identified and prioritized by groups disaggregated by gender, wealth, and age. This was followed by the development of a formal action research proposal. Since then, a number of research activities have been launched to develop integrated solutions to prioritized problems related to the management of soil and water, vertebrate pests, trees, and springs. Two years after the commencement of activities, positive results were observed for most of the activities undertaken—many of which had not been attempted before by research institutions or NGOs (e.g., equitable dissemination of technologies, porcupine control). The team decided to undertake a field day to demonstrate and scale out the initial results to various stakeholders from within and outside the pilot site (see Plate 15).

In 2007, the Areka site team organized a field day to scale out experiences from Gununo watershed. Over 236 participants from various institutions participated, including research centers (Awasa and Holleta Agricultural Research Institutes), directors from national and regional agricultural research institutes (EIAR, SARI), institutes of higher learning, the Bureau of Agriculture at different levels (regional, zonal, district), Council members at different levels (zonal, district, and peasant association), NGOs and farmers in and outside of the watershed. News agencies (national and regional TV and radio) were invited to help document the event and related innovations and share them with a wider public. In the course of the day, participants visited sites where different technologies and approaches had been applied. Leaflets on different topics were prepared for participants, and over one hundred copies were distributed among them. News of the experiences received media coverage in the national language on Ethiopian Television and Southern Nation Television and Radio. The team also made an arrangement with the news agencies to host a special TV program for wider dissemination, and to have an additional radio program aired in the local language spoken by farmers in Gununo watershed and surrounding areas. The impact of the field day has included increased demand for technologies and approaches by farmers in neighboring villages, government agencies, and NGOs. It has also led to an expanded membership in village research committees, including farmers from neighboring villages who had not participated in pilot research activities, thus scaling out technologies and approaches beyond the watershed.

Lessons learned

The following lessons have been learned through AHI's early efforts to scale out proven innovations from benchmark sites:

1. The first approach to scaling out, in which a high profile activity is implemented and well advertised, is effective only for activities that carry a very high value among local communities, and can therefore muster political support for scaling out.

2. Farmers often need organizational training more than technical training to enable them to adopt or sustain an innovation. Key competencies include articulating their demands, developing institutional capacities (e.g., for accessing input or output markets or ensuring technologies are equitably multiplied and disseminated), improving natural resource governance (e.g., implementing local by-laws in support of technological or other innovations), and monitoring and evaluating innovations.

3. Practical field demonstrations and inter-community visits are vital elements of scaling out, because they enable farmers and other stakeholders to understand how the technology or practice works and observe the benefits in situ.

4. Institutional dependency needs to be overcome if scaling out is to be sustained. Success cases have indicated that in order to overcome any given problem, farmers need ready access to all the necessary elements that enable them to adopt, adapt, and disseminate new technologies and practices that they have found attractive. These include increased organizational capacity, access to appropriate materials for implementation and maintenance of the innovation, and technical support when problems arise.

5. The use of participatory monitoring and evaluation and process documentation tools is helpful not only in guiding the change process, but also in providing information on outcomes and impacts accruing from R&D efforts. These tools generate information that is complementary to that which is normally collected by researchers (which tends to focus on quantitative, and often biophysical indicators such as yield or soil fertility), such as the performance of indicators of importance to farmers. This information is essential to bolstering support for the innovations among actors seeing them for the first time.

6. Radio is a very effective tool for raising awareness on an innovation to a large audience; however, it is insufficient for imparting the necessary knowledge and skills to ensure effective implementation. Thus, effective scaling out requires both awareness creation and support to formal efforts to train others and help them trouble shoot during their efforts to implement complex methodological innovations. Fortunately, piloting an innovation develops human resource capacities within villages and institutions that can in turn be leveraged to support the spread of innovations, provided these individuals are empowered with the necessary training/facilitation skills and financial resources.

7. Responsiveness of research and development institutions to farmers’ articulated needs is critical to ensuring the effectiveness of any scaling-out effort. In order to maintain the interest of the intended beneficiaries of any scaling-out effort, it is important that time is taken by researchers or development professionals to understand their problems, that attractive options be made available and that timely actions are taken to respond to farmer demand. This represents a challenge for most institutions or projects, particularly those constrained by inadequate human and financial resources. For instance in Tanzania, the ratio of extension agent to farmers is 1:1600. It is also constrained by institutional approaches that are supply- rather than demand-driven.

8. A comprehensive approach to scaling out that considers various requirements to successful adoption of the technology or approach is essential. This includes strategies for raising awareness, for building capacity, for availing the necessary inputs (technological or other), and for monitoring the spread and performance of the innovations. Capacity development efforts often involve more than a one-off training in the classroom; practical implementation is generally required for adequate assimilation of new technologies or practices.

9. For scaling out to be effective, partnerships with new actors beyond agricultural research are important. This is true for several reasons. In the absence of such partnerships, bottlenecks to participatory processes are quickly reached as communities express needs that go beyond the institutional mandate of research. Second, with limited communication and harmonization of efforts, different organizations may pursue conflicting goals or duplicate efforts in some locations while leaving other locations with no services. There may also be a need for research institutions operating at different levels or in different locations to coordinate their activities for greater effectiveness. While partners may face challenges associated with divergent approaches, mandates, and resource levels, most important is that they share the same goals, philosophy, and eventual credit.

Self-led institutional change

In addition to scaling out technological and methodological innovations from benchmark sites to new watersheds and districts, AHI has supported processes of institutional change at national level. Institutional change is aimed at structural, procedural, and systems changes within R&D organizations to enhance the effectiveness of these organizations and their relevance to clients.

Most institutional change work in the region has been catalyzed by actors and factors outside of the organizations undergoing change (Chema et al., 2003). While this may also be true in the case of AHI, the institutional change processes carried out in partnership with NARS may be termed “self-led” because while AHI and partner organizations have provided the facilitation, the change process was largely self-propelled and self-managed by senior managers. In participatory reflection workshops, NARS managers and partners noted that for sustainable change to be realized, the change process had to start from within the organizations themselves (AHI, 2001). The managers indicated that self-led institutional change should start with development of better dialogue between researchers and managers, and then with external partners such as NGOs, extension departments, the private sector, and institutes of higher learning. AHI has engaged with NARS managers to facilitate their efforts to steer self-led institutional transformations, with the aim of ensuring that change is initiated and managed from within the organization. This has enabled changes to be aligned with organizational and national policies and priorities. This means that NARS stakeholders jointly reflect on the key aspects that they would like to change and then internally develop solutions and strategies for managing the change process.

While a general focus on poverty alleviation is clear in the emphasis on institutional change in eastern African research institutions, more specific change objectives needed to be clearly articulated. As a result, AHI held meetings with NARS managers and researchers to discuss some of the main objectives of agricultural research, and the changes that are needed in national agricultural research systems to achieve these objectives (AHI, 1998; 2001). Participants highlighted the following changes in organizational policies, structure, and function that are required to enhance their effectiveness in contributing to poverty alleviation:

1. Enacting policy reforms in research and extension agencies to ensure that participatory approaches become part and parcel of researchers’ daily routines. It was observed that such reforms necessitate new incentive schemes so as to motivate staff and reward them for their efforts. Stakeholders identified reluctance of managers to experiment with innovative reward mechanisms as a key barrier to institutionalization of participatory approaches. They stressed decentralization of authority from headquarters to research stations and accountability to stakeholders as the main strategies to ensure demand-driven approaches to R&D.

2. Strengthening and targeting research activities through improved consultation with end users. This includes two key elements: farmer participation in defining desired changes and the contributions of research to these, and the need to strengthen farmer organizations to enable them to participate effectively in defining research priorities and articulating demand for advisory services. The National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) of Uganda, for example, has restructured its programs to shift from a commodity-based to a thematic focus to ensure that farmers’ priorities and participation are at the center of research activities (see www.naads.org).

3. Strengthening the interface between research and extension, especially at local, district, and regional levels. The general trend is for research and extension to work independently of one another, creating unnecessary competition over resources and resulting in the dissemination of contradictory information to the public. In Uganda, stakeholders envisioned a stronger relationship between NAADS and NARO through zonal agricultural research institutes and NAADS district operations.

4. Developing systems for experiential learning and action research in support of institutional learning and change. Stakeholders identified the iterative process of planning, action, reflection, and feedback (among implementers, and with farmers and policy makers), replanning, and continuous improvement as key to meeting any challenge associated with impact-oriented research and extension. Part of this strategy includes the need for an effective and flexible system for data capture and analysis, so that information on the effectiveness of approaches under development is accessible to decision-makers.

5. Creating and strengthening innovation platforms, networks, and systems for communication, documentation, and dissemination. Strategic partnership arrangements were seen as a key ingredient to achieving impact, to capitalize upon synergies in institutional mandates, skills, and resources. For example, demands emerging out of participatory problem diagnosis and prioritization that do not fall within the mandate of one organization can be more easily accommodated if organizations with diverse mandates are working in partnership. Similarly, action research to develop methodological innovations in research and development requires contributions from both research and development agencies.

6. Bolstering support from senior leadership. As institutionalization of participatory and impact-oriented research approaches was required to accelerate impacts, AHI and NARS partners were of the view that the process needed the support of the top leadership within the organization—both to reflect on their readiness to engage in change, and to develop the necessary mechanisms to support it.

AHI support to self-led institutional change agendas has gone through several phases. From 2002, an attempt was made to pilot the institutionalization of participatory research approaches together with researchers, managers, and their development partners so as to make them common practice in selected NARS. These efforts have evolved to encompass a wider array of approaches, such as integrated research and innovation systems approaches. Organizations that have been involved in these efforts included the Department of Research and Development of Tanzania, the Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization,4 and, more recently, the National Agricultural Research Organization of Uganda and the Institut des Sciences Agronomiques du Rwanda. AHI and its partners aimed to catalyze changes among the NARS partners so that approaches proven to be effective become institutionalized. This implied developing new ways of interacting and engaging with other stakeholders, among other internal changes in organizational structure and function.

Approach development

Two approaches may be highlighted based on where the impetus for change originated from, whether the external environment or the beneficiaries themselves.

Approach 1—Self-led institutional change catalyzed by external drivers

The first approach involves changes induced by external drivers, such as donor agencies, new government policies or global trends (e.g., newly acquired knowledge or development strategies, shifts in the global economy or climate change). Since change cannot be effective without local ownership, the approach involves collaboration with internal managers and leaders of R&D organizations so that the change process is driven and managed from within.

The following primary steps were taken in the AHI context:

1. An external push for change in the way research and development practices are undertaken occurs. One prominent example is the recent push by donors, politicians, and civil society for research and development organizations to show impact, and increase the rate and scale over which impact is achieved.

2. Managers and other stakeholders visualize the changes they would like to see, often with the help of an external facilitator. Visualizing change often involves a search for evidence of what works in practice, so as to ground change in proven practices rather than in theory alone. Within public research organizations, for example, managers are demanding that evidence of impact from new approaches be gathered to enable them to make informed decisions about new investments (e.g., reallocation of budgets and staff time). Visualizing change may also involve developing a framework to highlight the scope of changes required, to plan for these, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the process as it is implemented (Box 6.3).

BOX 6.3 DEVELOPING PERFORMANCE CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE

In Ethiopia, an assessment framework was developed by asking workshop participants, “If research were highly effective, what would stakeholder X be doing differently?” The question was asked of farmers, farmer organizations, researchers, and research organizations, to highlight behavioral changes that would occur at diverse levels if the envisioned outcomes were achieved. Answers to this question helped in the development of a set of performance criteria against which institutional changes were evaluated during implementation.

3. “Best bet” approaches are identified. Before getting started with the self-led change process, organizational leaders assess internally their own projects or those of other agencies to identify key approaches and lessons that can be institutionalized. In Ethiopia and Tanzania, for example, eight projects using participatory research were assessed to give managers insights on best practices and conditions for successful outcomes to be achieved. A standardized structured questionnaire was employed to collect data about the approaches employed by and results emanating from each of these projects. Analysis of all the case studies and discussions that followed provided a basis for defining critical success factors or “cornerstones” for effective research (Figure 6.3). These cornerstones were in turn utilized to design an institutional change strategy, and to monitor and evaluate the performance of this strategy during its implementation.

4. Piloting of the innovation in selected sites or research centers. Prior to engaging in organization-wide change processes, pilots are used to test whether the new ideas/approaches are feasible within the new institutional context. This helps to build capacity in applying the innovation in practice and also highlights key activities that must be undertaken to ensure the innovation is successfully internalized. Only once these pilot experiences have proven successful are efforts made to institutionalize them within the organization as a whole.

FIGURE 6.3 Cornerstones for effective research in Ethiopia and Tanzania

5. Synthesis of lessons learned. The lessons from the change process are documented continuously and synthesized for wider dissemination. This synthesis enables key lessons to be distilled on what did and did not work well, which then guides efforts to expand the approach within the wider organization.

6. Institutionalization of changes based on lessons learned. Once the lessons are synthesized, the managers of the research or development organization utilize them as ingredients for institutionalizing the approaches. Institutionalization is meant to ensure the approaches become routine and are applied in everyday activities of the organization. This requires allocating budgets and staff time to these activities in all research centers and/or among all staff, and mainstreaming the activities into annual planning and review processes. In some cases (only where needed for effective implementation), structural changes may be required—for example, the creation of new units to enhance interactions among disciplines or with outside actors. Such institutional reforms begin during the piloting phase, but are often expanded at this time as they require commitments from senior management or the organization's headquarters.

An example from Rwanda is illustrated in Box 6.4.

BOX 6.4 SCALING UP AND OUT AHI APPROACHES TO INRM: THE CASE OF ISAR IN RWANDA

Limited adoption of NRM practices by smallholder farmers in Rwanda had led to increasing soil erosion and subsequent siltation of cultivated wetlands and valley bottoms. Research and development approaches were ineffective in catalyzing shifts toward more sustainable NRM. Limitations of the conventional approach included an emphasis on individual components rather than on component interactions or systems; a top-down approach to technology development and dissemination with limited involvement of intended beneficiaries (and developed technologies failing to reflect farmers’ priorities or realities); a focus on the plot and farm level (which left issues operating at other spatial scales or requiring collective action unaddressed); failure to link technological innovation with other complementary innovations (e.g., supportive market linkages or policies); and limited collaboration among relevant research and development partners. The composition of research teams (with few social scientists or researchers with skills in integrated approaches) and high staff turnover were further impediments to implementing desired institutional changes. This called for an approach for encompassing broader units of analysis and intervention and which takes into account both the biophysical and social dimensions of NRM. To accommodate these requirements, the Institut des Sciences Agronomiques du Rwanda (ISAR) adopted the AHI approach to INRM to address the diverse factors responsible for natural resource degradation in Rwanda.

Initiatives taken to address the problem

The development and implementation of watershed management plans for integrated NRM was identified as a major thrust over the next two decades in Rwanda's agricultural sector master plan. Subsequently, ISAR sent two scientists to India to explore the possibility of learning from this country's experience with participatory watershed management and explore the possibility of a south–south partnership to leverage benefits from past experiences in both countries. With World Bank support, ISAR also recruited a group of “experts” in different professional fields outside Rwanda to support capacity development following the genocide. In 2005, one of the senior scientists recruited by ISAR, a former AHI benchmark site coordinator, was hired to support institutionalization of the watershed management approach within ISAR. The following steps were followed:

1. A country-wide tour to different agro-ecological zones was organized for newly recruited scientists.

2. The integrated watershed approach was introduced to ISAR management and scientists.

3. The ISAR DG requested that capacity building on INRM be conducted for all ISAR scientists.

4. Two training workshops, sponsored by the Government of Rwanda, were conducted at ISAR headquarters.

5. The ISAR DG agreed to sponsor watershed-level INRM pilot activities in three pilot sites (and to subsequently increase this to four sites).

6. Watershed teams comprised of all disciplines were formed, and local development partners engaged.

7. Selection of pilot sites by research teams in collaboration with farmers and district partners.

8. Introduction of the approach to watershed communities.

9. Selection (by farmers) of representatives to work with the research team, taking into consideration hamlet representation and farmer categories (age, wealth, gender, landscape location of plots).

10. Implementation of participatory diagnostic surveys to identify constraints and opportunities for overcoming these constraints.

11. Prioritization of identified issues by farmers, with facilitation of the research team.

12. Feedback of results to watershed communities and other stakeholders.

13. Participatory preparation of community action plans (CAPs).

14. Implementation of CAPs, and periodic follow-up by the research and development team.

15. Lessons learning from pilot watersheds to explore the potential for institutionalizing the approach throughout the organization.

Although the above steps in self-led institutional change have taken place within the selected NARS, variations in the approaches used in different countries have been noted. Box 6.5 illustrates how self-led institutional change may be catalyzed by different drivers—whether national policy priorities or donors.

BOX 6.5 NATIONAL POLICY PRIORITIES AND DONORS AS DRIVERS OF INTERNAL CHANGE IN NARS

In Ethiopia, the director of research, managers, and researchers were under pressure by government ministers and members of parliament to provide evidence of impact from agricultural research in order to secure ongoing funding for their activities. The recurrent drought and food insecurity had created pressure on the government to deliver interventions to mitigate these challenges. In the case of Uganda, donors demanded evidence of impact from the work that had been funded. This led the Director General of NARO to bring in external consultants from ICRA and Makerere University to design a workshop on integrated agricultural research for development (IAR4D) as a new way of conducting research that would show rapid impacts among target beneficiaries. All 13 zonal agricultural research and development institutes (ZARDI) attended these workshops and developed action plans that they implemented when they returned to their respective research stations to practice what was learned in the workshops.

Box 6.6 illustrates how the key steps in institutional change may vary according to context and the priorities of stakeholders involved.

BOX 6.6 VARIATIONS IN INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE PROCESSES LED BY EIAR AND NARO MANAGERS

Steps in institutional change in the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR):

1. Inception workshop with managers on what needs to change

2. Learning and experience sharing workshops combined with training

3. Field-based implementation of action plans generated in workshops

4. Follow-up by AHI Regional Research Team and managers on implementation of action plans

5. Synthesis of lessons and insights from workshops and the field

6. Dissemination of lessons and insights to managers, researchers, and regional stakeholders.

Steps in institutional change in the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO):

1. Institutional change facilitators’ design workshop for senior managers

2. Workshop on institutionalized responses to research and development challenges for representatives from zonal agriculture research and development institutes (ZARDI)

3. Workshops for staff of research stations implementing pilot experiences

4. Piloting of innovations at station level

5. Mid-term evaluation

6. Adjustments in the approach formulated based on recommendations from the evaluation, and proposal developed and submitted for funding.

Approach 2—Self-led institutional change catalyzed by grassroots demand

A second approach to institutional change is catalyzed not by external actors, but by grassroots demand. While change is initiated from below, it also requires responsiveness to farmer demands among service organizations—and is thus often conditional on a favorable institutional and policy environment or organizational leadership.

The following steps are key in enabling institutional change based on grassroots demand:

1. Grassroots problems identification, facilitated by an independent party. In contexts where farmers are not adequately organized, the articulation of grassroots demand may require the involvement of an independent party. In cases where community-based organizations are strong and networked at higher levels, this demand may be expressed spontaneously.

2. Information sharing or advocacy with district and national policy makers. Once demands are articulated, identified changes must be advocated to leverage the necessary political will to support these changes among policy makers or institutional managers (depending on the nature of changes desired).

3. Gathering of evidence that identified changes are in fact able to leverage the purported benefits. As mentioned above, policy makers and managers will often require evidence that the proposed change works in order to justify changes in policies, institutional practices or budgets. Where such an innovation has already been implemented in practice, evidence can be gathered from these existing cases. Where such cases do not exist, evidence can only be gathered through the piloting of innovations and documentation of observed changes (for example, using an action research approach).

4. Lessons sharing at diverse levels (e.g., national fora, cross-district exchange visits) to influence other actors to invest in the innovation.

5. Scaling up or institutionalization of the innovation with monitoring, to enable mid-course adjustments to be made.

For an example of this approach, please see Box 6.7.

BOX 6.7 LINKING FARMERS TO POLICY MAKERS: THE ROLE OF ACTION RESEARCH IN FARMER INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

A host of challenges have been experienced in the delivery of public sector services in developing countries: matching services to felt needs of beneficiaries, enabling effective stakeholder participation, ensuring equitable coverage and representation of diverse social groups, efficiency and effectiveness in service delivery, and overcoming barriers to information flow. The National Agricultural Advisory Services of Uganda (NAADS) is a program for demand-driven extension provision that relies on local institutions (farmer fora) to articulate farmers’ demands from private service providers. While NAADS policies provided the institutional framework for effective demand-driven service delivery, a number of concerns were raised by intended beneficiaries about its effectiveness in practice.

Initiatives to address the problem

AHI, CARE, and other organizations operating at community level throughout the district had observed a host of complaints leveraged by farmers about the implementation of NAADS. One key concern was the limited effectiveness of farmer fora in representing all of the villages in their jurisdiction and in ensuring downward accountability in the management of financial resources and services. In response to these concerns, AHI and CARE formed the Coalition for Effective Extension Delivery (CEED) with other concerned organizations to support stakeholders in addressing these concerns. Key steps in the process included the following:

1. Identification of critical bottlenecks to the effective functioning of NAADS. This was done by consulting diverse stakeholders involved in implementing the program or intended to benefit from it (e.g., male and female farmers). The limited effectiveness of farmer institutions was identified as one key barrier to effective program implementation.

2. A participatory diagnostic activity was carried out in one parish where CARE was working to assess the problem more deeply from the perspective of the intended beneficiaries. The primary concern related to farmer representation was poor coverage of services for parishes geographically distant and politically disconnected from the farmer fora.

3. A participatory action research process was initiated with CEED facilitation, to support parish residents to find their own ways to overcome the problems of representation and accountability. This involved the piloting of institutional innovations recommended by farmers—in this case, the formulation of parish-level farmer fora to help represent and advocate on behalf of parish residents at sub-county level.

4. The performance of these pilot experiences was evaluated in order to formulate recommendations.

5. Feedback was provided to NAADS at national and district level, and CEED lobbied for institutionalizing the approach in other NAADS parishes/districts.

6. NAADS commissioned a national-level study by CEED on farmer institutional development to explore whether the same problems exist in other NAADS districts, as a key step in leveraging institutional commitment for reforms. Findings suggested the problems were very similar to those experienced in other districts.

7. Parish-level farmer representative bodies were adopted by NAADS and implemented in other districts under the name of parish coordination committees (PCCs).

Outcomes

NAADS implementation at parish level (i.e., planning, monitoring, and quality assurance of service delivery) has been strengthened as a result of PCCs. This has increased awareness and interest of farmers in the NAADS program, leading to improved outputs from program activities. PCC chairpersons have also been integrated into the sub-county farmer fora for improved information flow and overall coordination. The primary challenge is sustaining and maintaining the spirit of volunteerism within farmer institutions, as the members of NAADS farmer fora and PCC perform their roles without a wage.

Approach 3—Self-led institutional change catalyzed from within

The final approach involved institutional changes for which the impetus largely comes from within the organization itself. The external environment may be instrumental in either the creation of the institution or in providing inspiration to reforms, but the management is self-motivated to innovate in the development and/or reform of key organizational processes as a means to meet the core objectives of the organization. The following are key steps involved in such reforms:

1. Development of an institutional mandate, policies or guidelines that structure learning within the organization.

2. Exposure to innovations related to the overall mandate of the organization. This may occur through partnerships, literature review, field visits or internal monitoring systems that enable the identification of best practices or ‘nodes of innovation’ within the organization itself. This step may be particularly instrumental or time consuming cases involving a new organization for which all operational systems must be generated from scratch.

3. Direct involvement in an innovation and lessons learning process, either within partner organizations or from isolated cases.

4. Active improvement on the approach as the innovation process unfolds through periodic monitoring, reflection, synthesis of lessons learned and documentation. This has multiple functions, from improved performance of the innovation to better alignment of the approach with the broader institutional mandate and procedures.

5. Development of a strategy for institutionalizing the approach, including the formulation of action plans and formalization of partnership agreements required to apply the innovation at a larger scale (e.g., nationally, or institution-wide).

An example of this approach is summarized in Box 6.8, which profiles efforts to institutionalize the system for demand-driven information provision within NAADS operations in Kabale District. An example in which AHI played a more minor role in exposing the lead institution to innovations of possible relevance to the organizational mandate (as highlighted in Step 2, above) is presented in Box 6.9.

BOX 6.8 EFFORTS TO INSTITUTIONALIZE DEMAND-DRIVEN INFORMATION PROVISION IN NAADS

Once the system for demand-driven information provision developed under the ACACIA project and described in Chapter 5 was running on a pilot basis, AHI faced the challenge of how to institutionalize it before the project came to an end. Several options were considered. The most feasible of these was to institutionalize the initiative within NAADS, the Ugandan system for demand-driven extension delivery described in Box 6.7. NAADS had both the vision and the institutional infrastructure to accommodate demand-driven information provision. Parish coordination committees (PCCs), sub-county farmer fora and district farmer fora under NAADS provided a hierarchy of farmer institutions through which information needs could be articulated and delivered. PCCs were already responsible for articulating agricultural service delivery needs within NAADS, and their role could easily be expanded to encompass information needs. NAADS also had a district monitoring and evaluation team drawn from various government departments (production, planning, information) and civil society that could assume the functions of the Quality Assurance Committee set up under AHI–ACACIA. In an exploratory meeting, we discovered that not only was NAADS an opportunity for AHI, AHI was also an opportunity for NAADS. NAADS had faced a series of challenges in their efforts to nationalize a system for demand-driven service provision in agriculture, and saw the model as a potential means to address the following concerns:

• Ensuring service providers have quality and up-to-date information.

• The proliferation of service providers in NAADS districts had raised challenges for quality control, with some service providers less informed than farmers. At other times, contradictory information was provided by different service providers. NAADS saw the AHI–ACACIA model as a means to access quality information and to deliver it to service providers.

• Ensuring cross-fertilization among farmers and communities. Even within farmer groups at village level, farmers were unaware of what happens on the plots of other farmers. As one moves to the district level, such lost opportunities are magnified. Farmers also have indigenous technologies and knowledge that may be of relevance to other farmers and villages. Thus, a centralized information capture and delivery mechanism was seen as an excellent opportunity to achieve economies of scale in knowledge management at district level.

The final year of the AHI–ACACIA project was spent piloting the management of demand-driven information provision within NAADS with NAADS leadership, based on the following steps:

1. Document how the current system works for the NAADS Secretariat and district, to bolster commitment among a wider array of NAADS stakeholders. This included past activities, the value added, lessons learned, and implementation guidelines derived from the pilot phase.

2. Develop and pilot test a mechanism for sustainable demand-driven information provision by the district telecenter. This included: (i) the handover of ownership of the telecenter to the District Farmer Forum and development of mechanisms for its effective management; (ii) developing the terms of reference for contracting a private sector service provider to manage the telecenter; and (iii) contracting a service provider on trial basis under NAADS technical procedures and procurement system, with close follow-up monitoring by AHI and NAADS.

3. Bolster commitment and buy-in from the NAADS Secretariat. This was done by sharing preliminary experiences at the annual NAADS planning meeting, featuring the initiative in the Kabale District semi-annual review report and hosting a site visit for the Secretariat.

4. Harmonize NAADS and AHI procedures for articulating service delivery needs. This included: (i) developing an integrated protocol for articulating farmer needs for advisory services and information and for synthesis of information at the district level; (ii) pilot testing the protocol; (iii) conducting a training on the use of the modified protocol; (iv) mainstreaming the process into standard NAADS information needs assessments (twice yearly); and (v) raising awareness among farmers on the pathways through which they may request information on a regular basis.

5. Pilot test a mechanism for information needs articulation and delivery at sub-county level, and for linking farmers within the sub-county to the district service provider.

In practice, a number of challenges were encountered, among these:

• Frequency of information delivery. Information needs were articulated on a bi-annual basis within NAADS, limiting the agility of information feedback to farmers. An entire production season could come and go within such a period. Establishment of new service contracts at sub-county level and encouraging more proactive articulation of information needs by farmers on a regular basis were two ways envisioned to overcome this problem.

• Articulation of information needs. Under NAADS, sub-counties must prioritize few enterprises for service delivery in order to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery. Under AHI–ACACIA, the focus was much broader—encompassing just about any information need in the area of agriculture, marketing, and NRM. These challenges were addressed by adjusting information needs assessments under NAADS to accommodate a wider set of components (production, marketing, and NRM interests specific to the chosen enterprises). However, information on other enterprises, and on natural resource management concerns that go beyond specific crops or enterprises, was effectively excluded.

• Effective governance of the telecenters. Mechanisms for maintenance and upkeep of computers and other equipment in the telecenters raised a major challenge. NAADS was not in a position to pay salaries; the only means to embed telecenter operations in NAADS was by means of service contracts. The district telecenter would be treated as a priority enterprise for the district, with the same holding true at sub-county level. To ensure effective ownership and upkeep, ownership was to be given to farmers rather than local government—and managed through the district and sub-county farmer fora. The challenge, then, became how to ensure facilities owned by farmers but operated by private service providers would be well maintained.

This helps to illustrate the complexity of trying to mainstream a complex approach within existing institutional structures and mandates—and provides a clear case for embedding new institutional innovations within existing institutional structures that can potentially ensure their sustainability should they prove to be effective. While the learning process was ongoing at the time of writing, efforts to institutionalize the demand-driven information provision model under the NAADS framework had received acceptance by stakeholders at different levels. The NAADS Secretariat was also keen to scale it up to other districts.

BOX 6.9 THE IMPORTANCE OF “OWNERSHIP” OF THE CHANGE INITIATIVE BY KEY DECISION-MAKERS

Experiences of AHI and partner organizations in supporting institutional change suggest that senior level decision-makers are crucial to supporting any change process. These individuals play an essential role in aligning institutional policies and incentives in support of the envisioned change, so that staff are encouraged and enabled to participate in new kinds of activities. They also play an important role in availing the necessary resources for competence building at station and national level and for monitoring and evaluation processes to track learning and outcomes. In Ethiopia, high levels of political and financial commitment have now taken institutional change processes in new directions, with a focus on partnerships with development actors and the private sector, as well as clear impacts on agricultural practices and technology adoption. The pressure and will for change is filtering down to the level of researchers, who are keen to also see impact from their work. At the time of writing, pilot learning was ongoing in certain research stations in Uganda, but greater financial support from government and donors was required to support learning and scaling up.

Lessons learned

A host of lessons were learned through AHI's efforts to support institutional change processes within partner organizations. These include the following:

1. The essential role of political will and ownership of institutional reforms by key decision-makers. AHI experiences suggest that for changes to be successful, key stakeholders—particularly senior management—must be convinced that the new changes are needed and that the changes are both effective in achieving a desired outcome and feasible. This ensures internal ownership of the change process and enables the alignment of organizational resources with change objectives and processes (see Boxes 6.8 and 6.9 above). Building consensus for change requires time and resources, and should be carefully planned.

2. The importance of identifying and supporting “champions” of institutional change. The change process depended a great deal on local “champions” within the respective organizations to motivate others and catalyze change. In Ethiopia, the Director of EIAR and his deputies were the champions in steering the process. In Uganda, the Director General and Deputy Director in charge of outreach managed the process, providing leadership in the process of developing a strategic vision and building local commitment.

3. The critical importance of grounding institutional change on a clear vision, supported by evidence of what works in practice. In each of the cases profiled above, one of the first steps in improving the effectiveness of institutional practice involved a thorough analysis of current performance of priority innovations in order to assess their effectiveness. This is important both for leveraging the necessary political will for reforms, and for learning lessons on what works that can be built upon in efforts to institutionalize new approaches. Acquiring evidence will involve either comprehensive evaluations of approaches already being implemented (building upon rigorous impact assessment or evaluation methods), or the piloting of new concepts using rigorous action research. In the second case, approaches used as they are tested and adjusted over time, and the outcomes achieved at these different stages of innovation, are documented. It is also important to keep visions and expected outputs and outcomes realistic so that visible impacts can be demonstrated and the motivation for reforms can therefore be sustained. This can often be done by reflecting on challenges likely to be faced in realizing the vision and planning accordingly (e.g., to reduce the scope of ambitions or to implement measures to overcome these challenges).

4. The need to support synergies between different levels of organization when supporting institutional change. AHI worked very closely with NAADS staff at district level in implementing the NAADS program and piloting initiatives at community level, while also carrying out strategic nation-wide studies on behalf of the Secretariat. Feedback to the district NAADS coordinator and the Kampala-based Secretariat on lessons learned from these different levels of intervention and knowledge generation helped to inform the NAADS Secretariat on issues concerning institutional policy and strategies.