1

INTEGRATED NATURAL

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

From theory to practice

Introduction

Highlands worldwide are important repositories of biodiversity as well as water towers for vast lowland and urban populations. The highlands of eastern Africa are no exception, with the Eastern Arc mountains home to a host of endemic species and a globally renowned biodiversity hotspot (Burgess et al., 1998). Yet while the ecological importance of highland areas cannot be underestimated, neither should their cultural and economic importance. Surrounded in most eastern African countries by semi-arid lowlands, the highlands have historically been home to disproportionately large human populations attracted by good rainfall, relatively good soils, and—in some locations—the potential to develop vast irrigation networks (SCRP, 1996).

In the past four decades, the eastern African highlands have seen rapid population growth and unprecedented land-use changes (Zhou et al., 2004), heightening the challenge of sustaining the resource base while providing for a growing population heavily dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods. Population growth and inheritance practices have contributed to very small household landholdings, reducing incomes and food security and in turn undermining farmers’ capacity to invest in conservation activities, often characterized by delayed returns.

Population pressure has also caused people to expand into marginal hilly areas, increasing soil and water loss, and destroying unique habitats (Amede et al., 2001; Stroud, 2002). The erosion in collective action traditions and traditional authority structures at a time when interactions among adjacent landscape units and users are ever more tightly coupled has undermined cooperation in natural resource management and led to increased incidence of conflict (German et al., 2009; Sanginga et al., 2007, Sanginga et al., 2010).

Historical factors have also established powerful path dependencies in local attitudes and behavior that continue to undermine local natural resource management investments. Colonial era agricultural policies—externally imposed, coercive and often brutal—led to such an active resistance to soil conservation practices that they played a key role in the growth of organized resistance to colonial rule (Anderson, 1984; Throup, 1988). Fortress conservation policies in the colonial and post-colonial era have served as a similar disincentive to sustainable forest management (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2002; Colchester, 2004; Western, 1994). Shifts in political regimes and related land reform policies have also resulted in significant ambiguity in resource ownership and control, contributing in some cases to resource mining behaviors (Bekele, 2003; Omiti et al., 1999).

Yet if the colonial state “failed to show the farmer what tangible benefits the conservation effort would bring to the land ... [or to] provide an adequate incentive for this effort” (Anderson, 1984: 321), to what extent have contemporary natural resource management interventions done any better? Within the conservation establishment, fortress conservation policies and approaches have slowly given way to a host of decentralized approaches—variously labeled Joint Forest Management, Co-Management, and Integrated Conservation and Development (Blomley et al., 2010; Brown, 2003; Hobley, 1996). Yet with the bottom line almost always one of natural resource conservation, some authors have begun to question whether such approaches have shifted the burden of conservation to local people without corresponding shifts in authority and benefits (Nsibambi, 1998; Wells, 1992). Others question whether these more participatory approaches are even suited to biodiversity conservation (Oates, 1999; Terborgh, 1999). Furthermore, these efforts have focused almost exclusively on production and protection of forests, leaving what happens in surrounding “anthropized” landscapes either beyond the scope of concern or of interest only to the extent that it furthers conservation objectives within protection forests (Hughes and Flintan, 2001). Where real powers for forest management have been devolved to local communities, it has often been where resources are already degraded and therefore of limited economic or conservation value (Blomley and Ramadani, 2006; Oyono et al., 2006).

Within the agricultural establishment, on the other hand, natural resource management concerns are squarely focused on landscapes where the human influence on landscape structure and function is dominant. Early emphasis, still prominent among agricultural research and extension institutions, was placed on soil erosion and its effect on soil fertility decline—with smaller communities of researchers focused on crop and livestock pests, agro-biodiversity, and rangeland management. With the vast majority of agricultural scientists and practitioners emanating from biophysical disciplines, problem definition has focused almost exclusively on biophysical constraints, and solutions put forward to address these have been largely technological (German et al., 2010). Early approaches, still evident today in the structure and functions of agricultural research and extension agencies, stressed a unilinear “transfer of technology” (ToT) approach in which research diagnoses problems and generates technologies to address these and passes them along to extension agents, who in turn disseminate them to farmers (Hagmann, 1999). Criticized for limited adoption levels and inability of this approach to catalyze effective responses to local needs, the rhetoric—and to some extent research practice as well—has slowly given way to a focus on more participatory forms of research. This has led to the proliferation of new approaches to address deficiencies in the old model, from “on-farm research” (advocated to adjust technologies to local conditions), “farmer participatory research” and “participatory technology development” (seeking to integrate farmers’ criteria into technology testing and evaluation), and “farming systems research” (to take a more holistic look at farms as systems and explicitly address component interactions and the allocation of finite resources among multiple production objectives) (Byerlee and Tripp, 1988; Farrington and Martin, 1987; Haverkort et al., 1991; Walters-Bayer, 1989). While these approaches went a long way in adapting agricultural research and extension to local concerns and priorities, their institutionalization has been partial at best; the focus has remained largely technological and exclusive attention to the farm level and individualized decision-making has left many natural resource management problems unaddressed.

A host of newer approaches to conservation and natural resource management1 hold great promise in placing the nexus of ownership and control squarely with local institutions, taking a wider view on natural resource management (beyond the farm, beyond the biophysical) and linking local users with outside actors and institutions. Yet, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Colfer, 2005), the proliferation of jargon and rhetoric far outpaces efforts to operationalize them in practice (Rhoades, 2000; Sayer, 2001). This volume focuses on one such approach, Integrated Natural Resource Management (INRM), and tries to address this gap by profiling efforts to conceptualize the concept, develop and test approaches to operationalize it, and distil lessons learned. This chapter seeks to set the stage for the rest of the book by providing an overview of the INRM approach and how it is framed and interpreted in this volume, and by introducing and defining key concepts that form the “conceptual core” of the approaches profiled in the chapters to follow. The second half of the chapter is dedicated to an introduction to an eco-regional program operating in the eastern African highlands where the INRM concept was defined, piloted, and evaluated.

Integrated natural resource management

Key aims

Integrated natural resource management is a scientific and resource management paradigm uniquely suited to managing complex natural resource management challenges in densely settled landscapes where people are highly dependent on local resources for their livelihoods, thus heightening the tension between livelihood and conservation aims. The explicit effort to bridge productivity enhancement, environmental protection, and social well-being (Sayer and Campbell, 2003b) therefore makes INRM strategically relevant in such situations. The CGIAR (2001) defines INRM as “an approach to research that aims at improving livelihoods, agro-ecosystem resilience, agricultural productivity and environmental services. It does this by helping solve complex real-world problems affecting natural resources in agro-ecosystems.”2

Yet, what does this mean in practice? A wide variety of research, development and conservation actors would already claim to be working towards such aims without employing the INRM label. So what aims and features set INRM apart from other approaches designed to address complex agricultural and natural resource management challenges? The CGIAR Task Force on INRM identified a number of success factors in managing an effective INRM process (CGIAR, 2002). Grouped by organizational level, these include:

Research and development teams:

• Employment of a participatory action research, learning process approach by all.

• Partnerships built on mutual trust, respect, and ownership by all.

• Multi-institutional arrangements with clear roles and commitments.

• Effective facilitation and coordination of interactive processes.

• Cross-disciplinary adaptive learning of research teams and development agents.

• Explicit scaling up/out strategy, building on “to-be” successes and strategic entry points.

• Effective communication strategy.

Partner and target communities/institutions:

• Application of a participatory action research, learning process approach by all.

• Shared problem and opportunity-driven focus.

• Short-term gains through the process itself (rather than via “handouts”).

• Local organizational capacity for INRM.

• Access to knowledge, technological, policy, and institutional options.

Thus, the concept as it has evolved within the CGIAR emphasizes the process through which NRM innovations evolve. As stated by Hagmann et al. (2003), INRM is grounded in a learning paradigm, premised upon a social constructivist approach3 to development and grounded in learning process approaches. Yet what is the substance of INRM? Key proponents emphasize the following core aims (Campbell, 2001; Sayer, 2001; Voss, 2001):

• Fostering sustainable agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

• Enhancing local adaptive capacity (in agriculture, forestry and fisheries), while supporting adaptive management beyond community level (e.g., the evolution of NARS, government agencies, and international organizations into learning organizations).

• Acknowledging and addressing trade-offs in NRM through negotiation support.

• Emphasizing sustainable livelihoods through a client-centered approach.

• Solving real-world problems with partners through the integration of system components, disciplines, stakeholders, and scales.

Given the complexity of aims and the arbitrariness of “system boundaries” within multi-scale NRM initiatives, it is essential that these boundaries be set in some clear way (Campbell, 2001). Aside from bounding the “system” spatially, it is important to clearly define the nature of challenges to be addressed. While INRM could encompass efforts to reconcile local livelihood needs and NRM concerns with societal and global interests in environmental services emanating from rural areas, this volume makes an explicit effort to focus on the NRM concerns of local land users. It therefore focuses on natural resource management within landscapes managed by local resource users to meet their own livelihood goals, addressing issues related to protected areas only to the extent that these more “exclusionary” conservation efforts are of concern to adjacent land users. The scope of issues encompassed in subsequent chapters therefore includes the following:

• Stimulating farmer investment in natural resource management and adoption of land management innovations through innovative efforts to package and deliver technologies which address the livelihood and NRM concerns of farmers in an integrated manner.

• Addressing the social, economic, and cultural factors influencing NRM at farm and landscapes scales, including the pervasive tension between individual and collective goods.

• Improving farmer feedback to research, extension and development agencies within a social learning process, so as to exploit the complementary knowledge, skills, and mandates of different sets of actors in addressing pressing development and NRM problems.

• Achieving synergies between local technological, institutional, market, and policy innovations in NRM.

• Enabling higher-level innovations within research and development institutions to support local resource users, foster synergies in knowledge and skills, and institutionalize lessons learned.

Conceptual overview

This section provides an introduction to some of the key concepts utilized to frame this book and the methodological innovations that underlie it. It therefore sets the conceptual foundations to the chapters that follow.

Integration

AHI has worked with the concept of integration in its efforts to pursue integrated research and development innovations since its inception. In the first two phases, this concept was advanced by the work done to foster synergies among diverse system goals at farm level. In many benchmark sites, for example, teams experimented with “linked technologies,” defined as a set of technologies whose benefits are best manifested when applied as an integrated whole rather than in isolation. For example, farmers experimented with soil conservation structures (bench terraces, fanya juu) stabilized with fodder, which was in turn fed to zero-grazed livestock in improved sheds, which in turn helped to make more efficient use of dung for fertilizing high-value crops on these structures. The integration concept is seen in the functional linkages established between system components (crops, livestock, soil, trees, water), which may be either ecological or economic. Ecologically, tighter nutrient recycling between crop and livestock components is designed to enhance the productivity of both crop and livestock components. From an economic standpoint, improved income from high-value crops on conservation structures may give farmers an incentive to invest in soil and water conservation, as well as additional disposable income. In Phase II the concept continued to be employed for achieving multiple and linked production objectives at farm level, but was further expanded to consider how integrated forms of support (e.g., technological, organizational, credit) to farm-level production could generate synergies and unlock change. Several years of systems modeling and experimentation in Areka, Ethiopia, also led to methodological innovations for understanding farms as systems—namely, integrated production units where multiple aims are pursued simultaneously in a context of limited financial, nutrient, and labor resources. It also led to strategies for enhancing component contributions to the wider farming system (as opposed to research efforts seeking to simply maximize returns to the component itself) and to participatory approaches to systems intensification.

During Phase 3, AHI began to experiment with integration concepts at the watershed level. These innovations helped to consolidate our understanding not only about what integration means at this level, but also overall. A typology of three forms of integration was developed during this phase to concretize current understanding of the integration concept (German, 2006). The first form, “component integration,” involves understanding and managing the impacts of any given component (or component innovations) on other parts of the system. Farm-level components include trees, crops, livestock, and soil, while landscape components include these same components plus common property resources (including water, both for productive and domestic use). “Integration” in this sense implies moving beyond component-specific objectives (i.e., maximizing the yield of edible plant products) and outcomes. Integration generally implies an optimizing logic, ensuring balanced returns to diverse system components (yields from tree, crop, and livestock components) or increasing biomass yield without depleting system nutrients or water. At times, optimization requires sacrificing yield gains in one component of the system so as to balance returns to other system components or goals. An example of this would be the selection of a crop variety that does not exhibit the highest grain yield, but yields an optimal return to crop and livestock components in the form of grain and plant biomass (for fodder). Yet the integration concept may also cater to the logic of maximization, common to market-oriented production systems, by elucidating the consequences to other system components (synergies and/or trade-offs) when maximizing outputs from one component. For example, research might quantify the effects of fast-growing tree species—chosen to maximize timber yield and tree income—on crop yield and income within the landholding and on adjacent farms, and on spring discharge. Understanding such trade-offs provides information on what is gained and lost to different system goals and land users, which may provide important inputs into development practice or policy.

The second form, “constructivist integration,” is more socio-political in nature—aiming to integrate the needs and priorities of different interest groups into research. “Constructivism” acknowledges that there is not one ‘correct’ view of reality but rather multiple, socially constructed realities (Chambers et al., 1992). In systems innovation, the priorities of these different social actors are actively solicited and integrated into the design of innovations. One form of constructivist integration is participatory research, in which farmers articulate research priorities and variables to be maximized or optimized. Variables that will often enter into research through participatory processes (and which would otherwise be absent) include those associated with risk; those exposing trade-offs related to the allocation of limited resources (land, labor, organic nutrient resources, capital) to different system components; and cultural variables such as those relating to local culinary practices and preferences (German, 2006). A second form of constructivist integration acknowledges the social trade-offs of current and alternative land-use scenarios by making explicit who gains and who loses from diverse types of innovations. By making social trade-offs explicit during the planning stage, alternative solutions or means of implementation can be considered that aim to optimize gains to diverse social actors while minimizing losses to any given one. By monitoring who wins and loses during an implementation process, creative strategies can be developed to ameliorate losses suffered by any given land user and to enable more equitable access to the benefits stream.

A third form of integration involves efforts to foster positive synergies among diverse types of innovations—for example, linking biophysical innovations to the social, policy, and institutional processes required to bring far-reaching change. This “sectoral integration” concept helps to frame scientific inquiry around the synergies among technological and other forms of innovation (social, organizational, policy, economic). The latter might include negotiation processes, participatory policy reforms and strategies to enhance market access so as to foster multiple goals simultaneously (i.e., income generation, equity, good governance, sustainable NRM).

Participation

“Participation” means different things to different people. All too often, however, it is taken to mean mere numbers of people present in community fora. AHI has been experimenting with ways to understand participation in more meaningful terms, by exploring the mechanisms and processes through which equitable development strategies and local empowerment may be achieved. Empowerment means enhancing people's ability—individually or collectively—to address their own concerns by leveraging existing resources and capacities and capturing opportunities. Equity, on the other hand, is about the fairness and social justice in the distribution of resources, opportunities, and benefits within a society. It is also about how approaches used by external facilitators or local change agents structure patterns of benefits capture.

Fostering these two goals requires experimenting with different approaches at different stages of farm and watershed-level natural resource management. It may involve attention to gendered participation and outcomes; strategies to mobilize communities around a common cause; mechanisms to ensure adequate representation of the many “voices” in large villages or watersheds through representational democracy (e.g., watershed structures and decision-making processes, socially targeted consultations); strategies to “level the playing field” between more and less powerful actors (e.g., stakeholder analysis, negotiation support); or instruments to hold people accountable to negotiated agreements (e.g., by-law reforms). Attention to participation is often concentrated at the planning stage of community interventions. Yet attention to equity and empowerment is needed at all stages—from problem diagnosis and prioritization to planning, implementation, and monitoring. At the planning stage, attention must be given to adequately capturing the diversity of “voices” in rural communities who may have different interests and goals. For farm-level innovations, it involves identification of variables of importance to male and female household members—not just to researchers or elite farmers. For watershed-level innovations, it involves instruments to explicitly capture a diversity of opinions when diagnosing problems, prioritizing, and planning. Similarly, during implementation and monitoring, it involves consulting diverse local interest groups (including participants and non-participants) on their views of how things are evolving to ensure diverse interests and concerns are considered when exploring how to improve upon ongoing change processes. Importantly, each of these phases of farm and watershed innovation requires attention to divergent opinions within communities, and means to reconcile these.

Collective action

Collective action may be defined as action taken by a group, either directly or on its behalf through an organization, in pursuit of members’ perceived shared interests (Marshall, 1998). This pursuit of common goals may go well beyond formal social structures (farmers’ groups) or direct activities carried out by such groups. In the context of AHI, we have experimented with a set of approaches to foster collective action in watershed management, leading us to identify a number of different forms of collective action (see German and Taye, 2008 for a related discussion). The first, and by far the most widely used, refers to direct actions carried out by groups of people working towards common goals (Lubell et al., 2002; Swallow et al., 2001; Tanner, 1995). This may range from two neighboring resource users managing a common boundary to the mobilization of large groups to work towards common interests. German et al. (2006) have called this the “social movement” dimension of collective action.

Another form of collective action involves collective regulation of individual actions (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002; Pender and Scherr, 2002; Gebremedhin et al., 2002; Scott and Silva-Ochoa, 2001). In other words, rather than involving direct actions by groups of people pursuing common goals, this dimension of collective action refers to collectively agreed-upon rules to govern individual behavior—often proscribing what “not to do” or individual responsibilities towards the group. Such rules are generally formulated to minimize the negative impacts of one person's behavior on another person or on an environmental service of public concern, or to bolster individual commitments to group activities. Such rule-making is often one element of other forms of collective action which enable them to work owing to the prior agreement on “rules of the game.”

Mechanisms for group representation in decision-making may also be considered another form of collective action. Given the sheer number of resource users in watersheds, equal levels of direct participation in decision-making on natural resource management or interaction with outside actors is seldom possible. Mechanisms for effective representation of all watershed users in decision-making and benefits sharing are therefore essential to minimize the tendency for elite capture of decision authority and benefits. This role of collective action has been included in collective action definitions of some authors (Meinzen-Dick et al., 2002), but features little in actual case studies.

A final form of collective action includes mechanisms for addressing power relations so as to achieve political equality. This dimension of collective action involves acknowledgment of diverse political interests around any given resource or management decision, and their effective integration into more equitable decision-making processes (Sultana et al., 2002). Issues of political equality among stakeholders have largely been addressed in the literature through case studies illustrating the “winners and losers” of development and conservation interventions owing to the frequent failure to establish mechanisms for equitable outcomes (Munk Ravnborg and Ashby, 1996; Rocheleau and Edmunds, 1997; Schroeder, 1993).

Watershed

The standard definition of watershed refers to a region of land drained by a watercourse and its tributaries to a common confluence point (outlet) (Pattanayak, 2004). However, given the AHI emphasis on participatory watershed management and an integrated approach to NRM, the spatial delineation of hydrological watershed boundaries was taken as only a tentative unit of analysis and engagement. These units were to be adjusted as the landscape-level natural resource management priorities of local users, and the spatial dimensions of these problems and related solutions, came to light. Following the participatory diagnosis of watershed problems, it was found that some “watershed problems” conformed to hydrological boundaries but many others did not. Problems related to the declining quality and quantity of water and the destruction of property from excess run-off, and the land-use practices contributing to this resource degradation, had clear hydrological boundaries. Yet many other landscapelevel natural resource management problems did not conform to hydrological boundaries. These included damage caused by free grazing, incompatible trees on farm boundaries, conflict surrounding protected areas, and pests and diseases. Yet even when problems may be defined by hydrological boundaries, solutions may be more readily found through the use of administrative boundaries. For example, spring rehabilitation may require village-level organizing and the support of government institutions whose mandate covers larger administrative units (e.g., districts), in addition to collective action among land users within catchment areas. In these cases, a flexible approach to defining watershed processes and boundaries was used. Use of the term “watershed” in this book is often, therefore, used interchangeably with the word “landscape.” Similarly, “watershed management” often encompasses problems and solutions whose dimensions extend beyond the biophysical realm altogether.

Institutional innovations

Addressing farm and landscape-level natural resource management problems—and capturing related opportunities—often requires innovation in the institutions that structure patterns of interaction among land users and other entities. Institutions may be defined as “rules of the game in society, ... the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North, 1990) or “decision structures” (Ostrom, 1994). Institutional innovations may therefore be defined as changes in the standard set of rules governing social behavior and in the social structures and processes through which decisions are made. AHI has experimented with each of these forms of institutional innovation. Innovations in organizational structure have included the testing of diverse forms of farmer organization for farm-level technological innovation, demand-driven technology and information provision, and policy innovation. It has also included the testing of novel organizational structures (platforms) to foster district-level collaboration in natural resource management. AHI experimentation with organizational processes has been even more extensive, as exhibited throughout this book. It has included processes for planning, for negotiating rules to govern collective action processes or natural resource management, for monitoring, and for enforcing agreed-upon rules. It has also included organizational processes for improving the effectiveness of innovations at farm, landscape, district, and national level (e.g. within national agricultural research systems). Finally, AHI has experimented with rules for governing how external resources (technologies, training, credit) will be shared within communities; for governing collective action processes (contributions to be made, benefits accruing to different members, and sanctions to be applied when contributions are not made); and for governing individual behavior at farm and landscape level (for example, to curtail certain practices having negative effects on other resource users or to negotiate and incentivize actions that individuals must take in addressing a common problem).

The birth and evolution of the African Highlands Initiative

The African Highlands Initiative (AHI) is an eco-regional research program working to improve livelihoods and reduce natural resource degradation in the densely settled highlands of eastern Africa. To this end, AHI has been developing and pilot testing an integrated natural resource management approach in selected highland areas of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda and institutionalizing its use in key partner organizations. AHI work targets the poor in degraded highland watersheds where environmental and related livelihood problems are widely visible on farms and landscapes and of concern to local residents due to their effects on livelihoods. It is this awareness and concern of natural resource management issues by local land users, rather than external conservation concerns, that has framed the scope of innovations tested by AHI.

The idea of a highland eco-regional program was tabled in 1992 at a regional meeting of the National Agricultural Research Institute (NARI) directors and International Agricultural Centers (IARCs) out of the concern that sustainable use of natural resources was given insufficient attention in agricultural research in the region. AHI was conceived as a NARI–IARC collaborative initiative aimed at improving farmer livelihoods while improving natural resource management so as to sustain rural livelihoods into the future. For most of its history, AHI has therefore operated as an eco-regional program of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and a regional network of the Association for Strengthening Agricultural Research in East and Central Africa (ASARECA), convened by the World Agroforestry Centre. While AHI's hosting arrangements have shifted over the years, and the focus of core innovations has evolved to build on lessons learned and address new challenges, its core vision of developing an integrated approach to improved livelihoods and better management of natural resources has remained unchanged.

The main impetus behind AHI's conception was a growing concern that the absence of a coordinated, inter-institutional effort had contributed to the limited adoption by farmers and communities of technologies and practices that improve and sustain natural resources. Although previous, independent research efforts had generated technologies to improve soil fertility and conserve water and other natural resources, they were not necessarily suited to the diverse socio-economic and biophysical circumstances of farmers living in the humid tropical highlands. Nor were farmer decision frames—the key considerations driving behavior, the “bottom lines” (e.g., food sufficiency and income generation in the near term) and the timeframe over which these are manifest—very often taken into consideration. Yet the ideas leading to the program's birth had less to do with the deficiency of research “inputs” to development and natural resource management (e.g., technologies, knowledge, decision tools) than with the limitations in the approaches through which the research–development interface was structured and these inputs brought to bear on the everyday challenges lived by rural households.

Implementing a regional research-for-development initiative involving multiple stakeholders at multiple levels, and accountable to different actors (farmers, national, regional, and international agricultural research institutes), is no simple task. It requires careful thought regarding institutional aims and design, key concepts that will help to anchor program evolution, and effective program governance (see Annex I). It also requires periodic evaluations to adjust program directions and governance as needed to effectively position the program to make unique contributions or to address challenges emerging through implementation. Adding to this complexity is the emphasis on the development and testing of new methodologies and approaches for integrated natural resource management (INRM) at different scales. This requires a strong methodological backbone to operationalize a social learning process at village, district, and higher levels and to link actors at different levels in a research and innovation process.

With these considerations as a background, the program was born with a mandate to do the following (Stroud, 2001):

• Develop a participatory approach to foster farmer innovation and adaptation.

• Employ an integrated systems approach rather than a commodity-based approach, so as to solve multiple and linked problems and make an impact on livelihoods and the environment.

• Develop a more integrated approach among research and development (R&D) actors in solving land degradation and related poverty issues.

• Give attention to social dimensions of natural resource management, such as local institutional arrangements for managing communal resources or issues of mutual concern.

• Consider how the short-term concerns of smallholders, which often override other considerations and lead to an inability or unwillingness to make investments with medium- to long-term returns, could be taken on board in efforts to support improved natural resource management.

• Explore mechanisms to identify and address external circumstances that act as disincentives to technology adoption—such as lack of market outlets, credit and input supplies.

• Interface with local and national policies that shape local natural resource management and the forms of institutional support to rural development.

Key phases in AHI's evolution

Since its inception in 1995, the AHI has been operationalized through discrete conceptual and funding phases of approximately three years each. This book reports on the first four phases of program evolution. In Phase I (1995–1997), a competitive grant scheme was employed to foster partnerships for multidisciplinary research in Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, and Uganda. Yet achieving changes in mindset and practices among those accustomed to working in isolation proved challenging in practice, leading to a reconceptualization of modes of operation. In Phase II (1998–2000), the program shifted away from the competitive grant approach to the use of benchmark sites as a means of operationalizing multidisciplinary approaches and teamwork for farm-level innovations. Eight benchmark sites were established and the geographical coverage was expanded to include Tanzania.

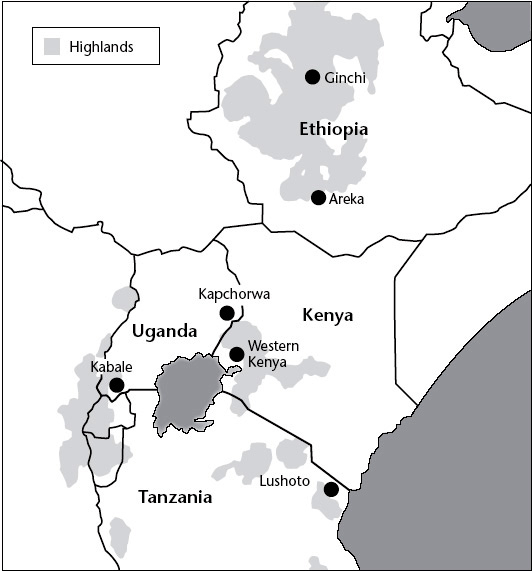

Following a favorable review of Phase 2, it was suggested that the program continue with the benchmark site approach in Phase III (2002–2004). It was also suggested that the number of sites be reduced, resulting in a reduction from the original eight sites to six (Figure 1.1). The program was also encouraged to shift focus from the farm to the watershed level, so as to address NRM issues that cannot be effectively addressed at farm level. Watershed and landscapelevel innovations continued in Phase IV (2005–2007), but greater emphasis was placed on institutional innovations to expand the reach of INRM in benchmark sites and to institutionalize lessons and approaches within the region. A more detailed description of each phase of work is presented in Annex II.

Operationalizing “approach development”

An important question underlying all of this work is the “how” of methodological innovation. How are new ways of managing natural resources identified? How are they tested in practice? And how are they evaluated for their effectiveness? There are two answers to these questions, one looking at the “big picture” of how collaboration is structured within benchmark sites and regionally to foster a culture of methodological innovation—and the other looking at the methodological framework through which innovation was fostered and lessons captured.

The regional “infrastructure” for methodological innovation

The organizational structure and functions of AHI are in many ways explicitly designed for enhancing methodological innovation. The most crucial ingredient has been the presence of functional research and development (R&D) teams in AHI benchmark sites, consisting of representatives of diverse disciplines and institutions with different mandates and organizational competencies (including, minimally, those working in the realms of “research” and “development”) and a well-facilitated process for collective deliberation and experiential learning. This was often operationalized through smaller theme-based teams and periodic meetings for cross-team reflection and replanning. A diverse institutional and disciplinary composition has helped ensure that efforts to conceptualize the “system” and the approaches to be tested are holistic and integrative. It has also helped to instill a more critical perspective on approaches under development, for example to ensure that unfounded assumptions are questioned. For example, the common misperception of communities as homogeneous entities for which interactions with or benefits flowing to one or more members will automatically constitute communication with or benefits to all can be regularly questioned by bringing experienced development practitioners into planning. This diversity of voices has also helped to ensure that work being done on diverse sub-components (e.g., soil and water, animal and crop husbandry) or themes (e.g., technological innovation, watershed management) harmonize their engagements with communities and one another.

FIGURE 1.1 Map of eastern Africa showing AHI mandated areas and the benchmark sites

Note: Two Phase II benchmark sites in Madagascar are not shown here.

Regional research team members, hired to fill gaps in disciplines and perspectives represented in site teams, have also played a critical role in periodic reflection and re-planning sessions. Their engagement with multiple teams at a time has enabled them to bring in unique observations from other sites, which may be at different stages in the implementation cycle or experimenting with different approaches. It also provides a unique “birds-eye” perspective that enables patterns and lessons to be captured across sites, thereby grounding the development of regional synthesis products within different thematic areas. Assisting site teams to distil lessons learned into Methods Guides and other public goods has been a fundamental step in coming “full circle” in the innovation and learning process, and in clarifying the overall role and institutional niche of AHI in the region.

The thematic focus of learning and innovation has been structured through external phase reviews, where broad targets for the next phase are set, and regional phase planning meetings, where representatives of all site teams and research managers come together to agree how to operationalize new concepts and first steps of methodological innovation. Key regional themes are distilled and used to structure learning by site teams, as well as regional team members who specialize in one or more of the themes. By Phase III, the key themes structuring learning and innovation across the program were consolidated into the following:

• approach for integrated natural resource management for watersheds;

• local organizational capacity for collective action;

• innovation systems through partnerships and institutional arrangements (alternatively called, “district institutional and policy innovations”);

• scaling up and institutionalization.

Different donors4 have historically funded different pieces of the whole (thematic and geographical), depending on their thematic and country priorities. This has resulted in a complex matrix of sites, projects and to some extent thematic thrusts, from which the methodological innovations and lessons in this book are derived. Having a set of cross-cutting thematic priorities and coordination functions at regional, national, and site levels has therefore been instrumental in ensuring the coherence of the program as a whole.

AHI's benchmark sites have also played a fundamental role in building and consolidating expertise in interdisciplinary teamwork, methodological innovation, and demand-driven research and development over time, and in linking levels of innovation. By having multidisciplinary and multi-institutional teams in place and a specific location where new ideas could be tested, an opportunity was provided for the mindsets and practices of individual professionals to evolve over time as well as for lessons to be more systematically learned and accumulated. At the time of writing, AHI had five active benchmark sites (BMS): Areka, located near Soddo town in south-central Ethiopia; Ginchi, located in the Galessa Highlands near Ginchi town, in central Ethiopia; Kabale, located in the Kigezi highlands of south-western Uganda; Kapchorwa, located on the foothills of Mount Elgon in eastern Uganda; and Lushoto, located in the West Usambara Mountains of Tanzania (Table 1.1). Each of these sites and the wider eco-regions in which they are embedded are characterized by high population density, natural resource degradation, and declining agricultural productivity—posing significant challenges to farmers to provide for a growing population while maintaining the productivity of basic resources (water, food, fuel, fodder). Benchmark sites are delineated by topographical boundaries (micro-watersheds), encompass from six to nine villages, and lie within larger administrative units (districts or woredas) where some of the activities take place. A more detailed description of these benchmark sites may be found in Annex III.

Methodological “nuts and bolts”

Once the institutional “infrastructure” for learning and innovation are in place, how are new methods actually conceived and tested in practice to derive broader lessons about the “approaches that matter”? Perhaps the most important component of this is that the innovations tested by different site teams are fully embedded in rural communities who have become equal partners in methodological innovation. While this element can be partially encompassed by the participatory research concept, in fact it goes much beyond a particular method of structuring farmer–researcher interaction. It may be best characterized by a broader philosophy of shared learning, inquiry and—perhaps most importantly—mutual respect and friendship. In sites where these interpersonal relations have been strongest and the mind-sets of R&D teams most flexible, methodological innovations have more quickly led to successful outcomes.

Another fundamental piece of the puzzle has been an emphasis on learning-by-doing rather than through pure data capture. Researchers were encouraged from early on in Phase II to “enter the system” rather than simply study it as outsiders. As this approach flies in the face of centuries of empiricism emphasizing the neutral observer, it was perhaps the most difficult challenge faced by AHI researchers. While lessons are therefore still being learned at a rapid pace, the approach was advanced considerably during Phases III and IV in efforts to operationalize the concept of “action research” in the context of INRM. This has led to the development not only of methodological innovations for INRM (action research “outputs”), but to innovations in the methods employed to structure learning itself (action research methods). The latter include tools for planning (e.g. action research protocols), tools for observing “process,” monitoring systems (German et al., 2007; Opondo et al., 2005), and approaches for integrating empirical and action research approaches (German and Stroud, 2007).

Action research is exactly what it sounds like—action-oriented research. It focuses explicitly on process, in this case the processes of development and social change. In the context of agricultural development and natural resource management, this might include testing different approaches to enhancing farmer innovation; mechanisms for linking farmers to markets; strategies for improving governance of landscape processes (such as the movement of water, soil and pests); and approaches to institutional change (for impact-oriented research). By superimposing research or systematic inquiry on development-oriented actions by R&D teams, farmers, and policy makers, new lessons can be learned that may otherwise be lost to observation. These lessons are gained by creating spaces to reflect on processes being implemented at diverse levels—including what was done, how it was done, the outcomes tied to particular approaches, and lessons derived from these experiences. Lessons learning is also strengthened by making observation more systematic, for example by clarifying the area of concern (improved livelihoods, equity and sustainability); the framework of ideas that structure research (for example, key challenges to development, sustainability or equity and related knowledge gaps) (Checkland and Holwell, 1998); the research questions (which often emphasize how to address these challenges); and the methodology (what will be observed and documented, and how). Each of these helps to sift out what is significant from the sum total of what is learned and observed—in other words, to determine which findings really count as knowledge (Checkland, 1991; Checkland and Holwell, 1998).

TABLE 1.1 Characteristics of African Highlands Initiative benchmark sites

Action research is different from empirical research in both the questions asked and the methods used. Action research questions are the “how” questions seeking answers to the question, “what works, where and why?” They are questions about development and change. While action research is embedded in an action context (i.e. community-driven watershed management activities), the “research” component helps to promote systematic inquiry about the change process. This can serve two purposes. First, it can encourage systematic reflection at the level where change is taking place (e.g. community, district, institution) on how things are being done so that they can undergo continuous improvement and have a higher chance of success. The second purpose is unique to action research—namely, to derive general principles from the change process that can be of use to other actors (farmers, research and development institutions, policy makers) outside the immediate location. In the context of AHI, for example, we study change processes for the purpose of developing methods and approaches that work in meeting different livelihood or NRM challenges. Without such scrutiny of the method-in-practice, it would be impossible to make reliable claims about the method's usefulness in solving real problems on the ground. This requires both participatory assessments of the methodology and systematic scrutiny at the level of R&D teams.5 Empirical research, on the other hand, is a more controlled form of research which helps to address the “what” questions. It requires more formal data collection protocols and analysis, but can be equally instrumental in informing decision-making at the local level or among policy makers. Applications of empirical research in watershed management within AHI are explored in subsequent chapters.

Action research starts with participatory action research (PAR). PAR is a process in which the immediate beneficiaries themselves, whether local communities, institutional representatives or policy makers, play the primary role in designing and testing innovations. The objective here is to enhance impact in the context under study—whether community-level change processes, institutional change or policy reforms. However, as applied in AHI, action research does not stop here. AHI has a mandate to generate international public goods in the form of “working methods and approaches,” in this case for integrated natural resource management. Therefore, it was essential to move beyond solving site-specific problems to distil lessons of broader relevance for the international community. This requires an additional level of abstraction and analysis that may not be of interest to the immediate beneficiaries.6 It also requires a particular set of skills to link site-specific circumstances to a broader global community (knowing what challenges and knowledge gaps exist elsewhere); to observe fine details of process (observing how people react to processes when facilitated in certain ways, reading body language, understanding how process relates to outcomes); and to understand how to link the particularities of local-level learning with generalization. While the protagonists (immediate beneficiaries) play a fundamental role in defining research, monitoring progress, adjusting the approach and evaluating impacts, it is generally researchers who play a primary role in managing research quality and bringing a wider body of theory to bear on local innovations. In short, action research encompasses, but is not limited to, participatory action learning for solving localized NRM problems. For a better understanding of how AHI has operationalized the difference between participatory action learning and action research, please see Table 1.2 and Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2 Illustration of the relationship between action research (upper box) and PAR (lower box) (German et al., 2011)

TABLE 1.2 Distinctions between participatory action research and action research as operationalized within AHI

Source: German and Stroud (2007).

Before concluding, it is important to mention two questions of common concern by those new to action research. The first relates to validity, and the second to the role of empirical research. Many people are uncomfortable with the inability to structure controlled and replicable processes in action research, given how participation will inevitably lead to the divergence of processes in different sites—independently of how similarly structured the initial steps are. Some well-known action researchers are comfortable with prior clarification of an area of concern, framework of ideas and methodology as means to ensure validity in action research (Checkland and Holwell, 1998). Yet comparison can also play a fundamental role in lessons learning, to understand how diverse approaches and contexts structure outcomes. This comparison can be operationalized in both space and time. One way in which spatial comparison was employed in AHI to learn lessons was cross-site comparison around different AHI thematic thrusts. Learning across cases is also possible within individual benchmark sites, as in the case of negotiation support processes around different types of natural resource problems (excess run-off, spring degradation, free grazing). Yet comparison can also be employed within a single site and action research topic through a systematic temporal comparison of iterative approaches used and their outcomes (as measured by local and/or scientific indicators). While it may not enable broader generalizations to be made, such systematic learning within cases does yield a wealth of observations about processes that do and do not work in particular contexts.

Many researchers also wonder whether empirical research has a role to play in action research, and struggle with the relevance of their training to action research approaches. In watershed management processes, we have found four discrete roles for empirical research, which are highlighted in more detail in Chapter 3:

1. To characterize the social and biophysical dimensions of natural resource management problems, so that interventions may be effectively targeted.

2. To monitor intermediate outcomes of different approaches to solving any particular problem at different phases of an innovation process, particularly in cases where variables are difficult to observe or monitor by local residents but nevertheless can help determine whether the approach is helping to foster community or program level goals (e.g., equity, sustainability).

3. To clarify complex cause-and-effect relationships that are difficult for farmers to observe, such as the effect of different land uses and their spatial arrangement on system hydrology and sub-service water flows.

4. To assess the impacts once the problem is solved, so that something can be said with confidence about the effectiveness of the approach used.

This said, it is important to clearly identify the “critical uncertainties” or program requirements that actually require costly empirical research investments. The tendency is for researchers to want to expand the scope of empirical research within participatory processes as a means to justify their engagement, and generate publications that conform with conventional standards of academic rigor. Ideally, these investments should be chosen carefully, based on gaps in local knowledge and observation capacity (as in the case of sub-service hydrology) and need (where the knowledge generated is required to identify an effective solution to a problem). In some cases, empirical research will be needed to fill gaps in local motives or to achieve project objectives. For example, participating farmers will tend to focus solely on their own benefits rather than on how to ensure equitable benefits captured by a broader community. This may require empirical research in social science to identify how opinions on issues differ within any given community, or to monitor how any given approach is structuring the distribution of benefits to different sets of actors. The same may be said about sustainability, given the tendency for farmers to focus on the immediate benefits from any given innovation. Empirical research that exposes the deficiencies of an approach from the perspective of equity or sustainability (e.g., only certain groups are benefiting, the innovation is leading to the depletion of nutrients) can help to raise awareness among the protagonists and encourage new innovations in the approach to address these gaps.

Main achievements

AHI program achievements are of three primary types: methodological innovations for INRM, impacts resulting from the piloting of these innovations, and various knowledge products. Regarding methodological innovations, the program has developed a host of methodological innovations for operationalizing INRM and addressing key natural resource management challenges. A summary of these innovations, and the publications where additional information may be sourced, is provided in Table 1.3.

Regarding the impacts emanating from these methodological innovations, an External Review and Impact Assessment of the program carried out in late 2007 and early 2008 identified the following key outcomes and impacts (La Rovere et al., 2008; Mekuria et al. 2008):

• male and female farmers have increased knowledge of technologies, and greater ability to demand these technologies and seek support from service providers and to freely express themselves with research and extension;

• improvements in crop production and yield owing to improved germplasm, better agronomic practices, better pest and disease management, and increased adoption of conservation practices;

• increased technology adoption owing to efforts to “link” technologies (see Chapter 2 for details);

• benefits associated with collective efforts to address farm-level productivity constraints, including improved access to information, training and credit; improved financial management and business planning; and access to community banks (the last of these unique to Lushoto);

TABLE 1.3 Methodological innovations developed by AHI and selected reference materials

| Theme and innovation | Selected reference materials |

| 1. Farm level innovations | |

Methods for systems intensification |

Amede, T., A. Bekele and C. Opondo (2006) Creating niches for integration of green manures and risk management through growing maize cultivar mixtures in the southern Ethiopian highlands. AHI Working Papers No. 14. Amede, T. and R. Kirkby (2006) Guidelines for integration of legumes into the farming systems of the east African highlands. AHI Working Papers No. 7. Amede, T., A. Stroud and J. Aune (2006) Advancing human nutrition without degrading land resources through modeling cropping systems in the Ethiopian highlands. AHI Working Papers No. 8. Amede, T. and E. Taboge (2006) Optimizing soil fertility gradients in the enset (ensete ventricosum) systems of the Ethiopian highlands: Trade-offs and local innovations. AHI Working Papers No. 15. |

System-integrated technologies with multiple benefits (Areka, Kapchorwa) |

Amede, T. and R. Delve (2006) Improved decision-making for achieving triple benefits of food security, income and environmental services through modeling cropping systems in the Ethiopian highlands. AHI Working Papers No. 20. |

Linked technologies (Lushoto) |

Masuki, K.F.G., J.G. Mowo, T.E. Mbaga, J.K. Tanui, J.M. Wickama and C.J. Lyamchai (2010) Using strategic “entry points” and “linked technologies” for enhanced uptake of improved banana germplasm in the humid highlands of East Africa. Acta Horticulturae 879(2): 797–804. Stroud, A. (2003) Linked Technologies for Increasing Adoption and Impact. AHI Brief A3. |

Use of entry points at farm level (all sites) |

Amede, T. (2003) Differential entry points to address complex natural resource constraints in the highlands of eastern Africa. AHI Brief A2. |

Farmer institutional development for |

Stroud, A., E. Obin, R. Kandelwahl, F. Byekwaso, C. Opondo, L. German, J. Tanui, O. Kyampaire, B. Mbwesa, A. Ariho, Africare and Kabale District Farmers’ Association (2006) Managing change: Institutional development under NAADS: A field study on farmer institutions working with NAADS. AHI Working Papers No. 22. |

Taye, H., M. Diro and A. W/Yohannes (2006) The effectiveness of decentralized channels for wider dissemination of crop technologies: Lessons from the AHI Areka site, Ethiopia. In: T. Amede, L. German, S. Rao, C. Opondo and A. Stroud (eds.), Integrated Natural Resource Management in Practice: Enabling Communities to Improve Mountain Livelihoods and Landscapes, pp. 265–73. Kampala, Uganda: African Highlands Initiative. Wakjira, A., G. Keneni, G. Alemu and G. Woldegiorgis (2006) Supporting alternative seed delivery systems in the AHI–Galessa watershed site, Ethiopia. In: T. Amede, L. German, S. Rao, C. Opondo and A. Stroud (eds.), Integrated Natural Resource Management in Practice: Enabling Communities to Improve Mountain Livelihoods and Landscapes, pp. 240–8. Kampala, Uganda: African Highlands Initiative. Woldegiorgis, G., A. Solomon, B. Kassa and E. Gebre (2006) Participatory potato technology development and dissemination in the central highlands of Ethiopia. In: T. Amede, L. German, S. Rao, C. Opondo and A. Stroud (eds.), Integrated Natural Resource Management in Practice: Enabling Communities to Improve Mountain Livelihoods and Landscapes, pp. 124–31. Kampala, Uganda: African Highlands Initiative. |

|

Negotiating equitable access to technologies (Areka, Ginchi) |

Mazengia, W., A. Tenaye, L. Begashaw, L. German and Y. Rezene (2007) Enhancing equitable technology access for socially and economically constrained farmers: Experience from Gununo Watershed, Ethiopia. AHI Brief E4. |

Methods for tracking farmer-to-farmer dissemination and impacts (regional/Lushoto) |

German, L., J.G. Mowo and M. Kingamkono (2006) A methodology for tracking the “fate” of technological innovations in agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 23: 353–69. German, L., J. Mowo, M. Kingamkono and J. Nuñez (2006) Technology spillover: A methodology for understanding patterns and limits to adoption of farm-level innovations. AHI Methods Guide A1. |

Catalyzing collective learning and innovation (Kapchorwa, communitybased facilitators in NAADS) |

Mowo, J., B. Janssen, O. Oenema, L. German, P. Mrema and R. Shemdoe (2006) Soil fertility evaluation and management by smallholder farmer communities in northern Tanzania. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 116(1/2): 47–59. Tanui, J. (2005) Revitalizing grassroots knowledge systems: Farmer learning cycles in AGILE. AHI Brief D4. |

German, L. (2006) Moving beyond component research in mountain regions: Operationalizing systems integration at farm and landscape scale. Journal of Mountain Science 3(4): 287–304 and AHI Working Papers No. 21. German, L., B. Kidane and K. Mekonnen (2005) Watershed management to counter farming systems decline: Toward a demand-driven, systems-oriented research agenda. AgREN Network Paper 45. German, L., A. Stroud, G. Alemu, Y. Gojjam, B. Kidane, B. Bekele, D. Bekele, G. Woldegiorgis, T. Tolera and M. Haile (2006) Creating an integrated research agenda from prioritized watershed issues. AHI Methods Guide B4. |

|

2. Watershed management and participatory landscape governance |

|

Sequenced methods for participatory integrated watershed management: • Participatory watershed diagnosis and characterization • The creation of functional clusters to structure innovations • Participatory watershed planning • Selection of entry points • Participatory monitoring and evaluation |

Adimassu, Z., K. Mekonnen and Y. Gojjam (eds.) (2008) Working with Rural Communities on Integrated Natural Resources Management (INRM). Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Addis Ababa. German, L., H. Mansoor, G. Alemu, W. Mazengia, T. Amede and A. Stroud (2006) Participatory integrated watershed management: Evolution of concepts and methods. AHI Working Papers No. 11. German, L., H. Mansoor, G. Alemu, W. Mazengia, T. Amede PhD and A. Stroud (2007) Participatory integrated watershed management: Evolution of concepts and methods in an eco-regional program of the eastern African highlands. Agricultural Systems 94(2): 189–204. German, L., K. Masuki, Y. Gojjam, J. Odenya and E. Geta (2006) Beyond the farm: A new look at livelihood constraints in the eastern African highlands. AHI Working Papers No. 12. German, L. and K. Mekonnen (2006) A socially-optimal approach to participatory watershed diagnosis. AHI Methods Guide B2. German, L., A. Stroud, G. Alemu, Y. Gojjam, B. Kidane, B. Bekele, D. Bekele, G. Woldegiorgis, T. Tolera and M. Haile (2006) Creating an integrated research agenda from prioritized watershed issues. AHI Methods Guide B4 |

Ayele, S., A. Ghizaw, Z. Adimassu, M. Tsegaye, G. Alemu, T. Tolera and L. German (2007) Enhancing collective action in spring “development” and management through negotiation support and by-law reforms. AHI Brief E5. Begashaw, L., W. Mazengia and L. German (2007) Mobilizing collective action for vertebrate pest control: The case of porcupine in Areka. AHI Brief E3. German, L., W. Mazengia, W. Tirwomwe, S. Ayele, J. Tanui, S. Nyangas, L. Begashaw, H. Taye, Z. Adimassu, M. Tsegaye, S. Charamila, F. Alinyo, A. Mekonnen, K. Aberra, A. Chemangeni, W. Cheptegei, T. Tolera, Z. Jotte and K. Bedane (2011) Enabling equitable collective action and policy change for poverty reduction and improved natural resource management in the eastern African highlands. In: E. Mwangi, H. Markelova and R. Meinzen-Dick (eds.), Collective Action and Property Rights for Poverty Reduction. Johns Hopkins and IFPRI, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. |

|

|

German, L., H. Taye, S. Charamila, T. Tolera and J. Tanui (2006) The many meanings of collective action: Lessons on enhancing gender inclusion and equity in watershed management. AHI Working Papers No. 17; CAPRi Working Paper 52. Tanui, J. (2006) Incorporating a landcare approach into community land management efforts in Africa: A case study of the Mount Kenya region. AHI Working Papers No. 19. |

|

Participatory governance of landscape processes: • Negotiation support • Participatory by-law reforms • Solutions to address specific landscape level challenges (spring rehabilitation, controlling free grazing, managing excess run-off, niche-compatible agroforestry, vertebrate pest control, co-management of protected areas) |

Adimassu, Z., S. Ayele, A. Ghizaw, M. Tsegaye and L. German (2007) Soil and water conservation through attitude change and negotiation. AHI Brief A6. German, L., S. Charamila and T. Tolera (2006) Managing trade-offs in agroforestry: From conflict to collaboration in natural resource management. AHI Working Papers No. 10. German, L., S. Charamila and T. Tolera (2005) Negotiation support in watershed management: A case for decision-making beyond the farm level. AHI Brief E2. German, L., W. Tirwomwe, J. Tanui, S. Nyangas and A. Chemangei (2007) Searching for solutions: Technology-policy synergies in participatory NRM. AHI Brief B6. Mazengia, W., A. Tenaye, L. Begashaw, L. German and Y. Rezene (2007) Enhancing equitable technology access for socially and economically constrained farmers. AHI Brief E4. Sanginga P., R. Kamugisha, and A. M. Martin. (2010). Strengthening social capital for adaptive governance of natural resources: A participatory action research for by-law reforms in Uganda. Society and Natural Resources 23: 695–710. |

Sanginga P., A. Abenakyo, R. Kamugisha, A. Martin and R. Muzira. 2010. Tracking outcomes of social capital and institutional innovations in natural resources management: Methodological issues and empirical evidence from participatory by-law reform in Uganda. Society and Natural Resources 23: 711–25. Sanginga, P.C., R.N. Kamugisha and A.M. Martin (2007) The dynamics of social capital and conflict management in multiple resource regimes: A case of the south-western highlands of Uganda. Ecology and Society 12(1): 6. Online at: www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art6/ Sanginga, P.C., R. Kamugisha, A. Martin, A. Kakuru and A. Stroud (2004) Facilitating participatory processes for policy change in natural resource management: Lessons from the highlands of southwestern Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences 9: 958–70. National Agricultural Research Organization, Kampala. Tanui, J., S. Nyangas, A. Chemangei, F. Alinyo and L. German (2007) Co-management of protected areas is about cultivating relationships. AHI Brief B7. |

|

3. District institutional and policy innovations |

|

German, L., A. Stroud and E. Obin (2003) A coalition for enabling demand-driven development in Kabale District, Uganda. AHI Brief B1. Tanui, J., A. Chemengei, S. Nyangas and W. Cheptegei (2007) Rural development and conservation: The future lies with multi-stakeholder collective action. AHI Brief B8. |

|

System for demand-driven technology and information provision |

Masuki, K.F.G., J.G. Mowo, R. Sheila, R. Kamugisha, C. Opondo and J. Tanui (2011) Improving smallholder farmers’ access to information for enhanced decision making in natural resource management: Experiences from South Western Uganda. In Bationo, A., Waswa, B.S., Okeyo, J. and Maina, F. (eds) Innovations as Key to the Green Revolution in Africa: Exploring the Scientific Facts (2): 1145–1160. Opondo, C., L. German, A. Stroud and E. Obin (2006) Lessons from using participatory action research to enhance farmer-led research and extension in southwestern Uganda. AHI Working Papers No. 3. |

4. Scaling up and institutionalization |

|

Self-led institutional change |

Mowo, J.G., L.N. Nabahungu and L. Dusengemungu (2007) The integrated watershed management approach for livelihoods and natural resource management in Rwanda: Moving beyond AHI pilot sites. AHI Brief D5. Opondo, C., P. Sanginga and A. Stroud (2006) Monitoring the outcomes of participatory research in natural resources management: Experiences of the African Highlands Initiative. AHI Working Papers No. 2. Opondo, C., A. Stroud, L. German and J. Hagmann (2003) Institutionalizing participation in East African research institutes, Ch. 11, PLA Notes 48. London: IIED. Stroud, A. (2003) Self-management of institutional change for improving approaches to integrated NRM. AHI Brief B2. Stroud, A. (2006) Transforming institutions to achieve innovation in research and development. AHI Working Papers No. 4. |

Methods for linking farmers to policy makers |

German, L., A. Stroud, C. Opondo and B. Mbwesa (2004) Linking farmers to policy-makers: Experiences from Kabale District, Uganda. UPWARD Participatory R&D Sourcebook. Manila: CIP. |

|

|

Action research |

German, L., W. Mazengia, S. Charamila, H. Taye, S. Nyangas, J. Tanui, S. Ayele and A. Stroud (2007) Action research: An approach for generating methodological innovations for improved impact from agricultural development and natural resource management. AHI Methods Guide E1. Opondo, C., L. German, S. Charamila, A. Stroud and R. K. Khandelwal (2005) Process monitoring and documentation for R&D team learning: Concepts and approaches. AHI Brief B5. |

Use of scientific and local knowledge to ground decision-making |

German, L., B. Kidane, R. Shemdoe and M. Sellungato (2005) A methodology for understanding niche incompatibilities in agroforestry. AHI Brief C2. German, L., B. Kidane and R. Shemdoe (2006) Social and environmental trade-offs in tree species selection: A Methodology for identifying niche incompatibilities in agroforestry. Environment, Development and Sustainability 8: 535–52; AHI Working Paper 9. Wickama, J. and J.G. Mowo (2001) Indigenous nutrient resources in Tanzania. Managing African Soils 21, IIED. |

Planning for integrated research and development interactions |

German, L. and A. Stroud (2004) Integrating learning approaches for agricultural R&D. AHI Brief B4. German, L. and A. Stroud (2007) A framework for the integration of diverse learning approaches: Operationalizing agricultural research and development (R&D) linkages in eastern Africa. World Development 35(5): 792–814 and AHI Working Papers No. 23. |

• improved livelihoods resulting from significant increases in agricultural income, and related improvements in housing, nutrition, and ability to pay school fees;

• improvements in water quality and quantity owing to the by-laws protecting water sources, restricted cropping near springs, and the cultivation of water-conserving vegetation;

• improved livelihoods owing to water conservation, resulting from reduced burdens on women, reduction in conflicts over water, the increased availability of irrigation water, and reduction in waterborne diseases and related medical expenditures;

• significant increase in the prevalence of collective action to solve NRM issues and cooperate on matters of common concern, and improved negotiation of resource conflicts;

• greater harmony at community level when dealing with the management of water sources/springs, boundary trees, and soil conservation issues;

• increased tendency to participate collectively in addressing NRM issues and comply with by-laws;

• increased confidence among farmers in their ability to solve NRM problems;

• significant improvements in access to information (i.e., on input and output prices, technology, financial services);

• more positive attitudes among farmers toward research;

• increased awareness and appreciation of watershed management in particular, and INRM in general, among many high level officials, leaders of institutions, and policy makers.

Impacts associated with wider dissemination of lessons learned and methodologies are impossible to assess, but the report notes that “the process of disseminating AHI outputs, successes, and methods is fairly effective at the international level”—in large part owing to the publication series, website, and regional trainings carried out for ASARECA member countries to disseminate select methods developed by the program. The assessment team also notes the program's role as a “think tank” for developing tools and methods, and for institutionalizing INRM at the regional level. The study concludes that INRM works so effectively owing to the interaction between AHI's biophysical and socio-economic components, and to AHI's community-driven approach. “The capacity to put INRM to work is a rare achievement within CGIAR centers” (Mekuria et al. 2008: 17).

Regarding AHI knowledge products, the program launched a series of AHI Briefs in 2003 and followed this up with a set of Working Papers, Methods Guides and Proceedings in 2006. These may be found at: http://worldagroforestry.org/projects/african-highlands/archives.html. In addition to contributing to this series, site and regional team members have collectively contributed to working papers of other organizations such as ODI's AgREN, CAPRi Working Papers, Managing Africa's Soils and IIED's PLA Notes. They have also published papers in academic journals such as Acta Horticulturae; Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment; Agriculture and Human Values; Agricultural Systems; Development in Practice; Environment, Development and Sustainability; Human Ecology; Journal of Mountain Science; Society & Natural Resources; Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences; and World Development, among others. They have collectively produced 195 publications, including 26 peer reviewed journal articles, two books, 23 book chapters, 39 working papers, seven methods guides, 33 briefs, 49 papers in workshop proceedings, and 16 program reports7 (Annex IV). The project also produced a number of knowledge products oriented toward farmers. As may be seen by the authorship, the vast majority of these publications were developed collaboratively by site team members, regional research team members, and other partners. The numbers of contributions made by different contributing partners are summarized in Table 1.4.

TABLE 1.4 Number of contributions made to different types of publications by different contributing partners

Publication type |

Number of |

Number of |

Number of |

Peer reviewed journal articles |

54 |

31 |

31 |

Books and book chapters |

97 |

20 |

4 |

Working papers |

75 |

51 |

25 |

Methods guides |

25 |

8 |

5 |

Briefs |

31 |

39 |

2 |

Conference proceedings |

134 |

37 |

32 |

Program reports |

19 |

15 |

0 |

Totals |

424 |

200 |

99 |

Conclusions

This chapter provides a brief overview of the concept, as defined in both the literature and in the research from which this volume emanates. A few key concepts are presented and defined to clarify the conceptual foundations of INRM and the chapters that follow. The chapter also provided an introduction to the African Highlands Initiative, the eco-regional program operating in the eastern African highlands under which the methodological innovations presented in this volume were developed and piloted. Following an introduction to the program's mandate and evolution, key strategies for putting INRM into practice and deriving lessons from experience were presented—along with a summary of key program achievements to date.