UNIT IV

Biodiversity and its Conservation

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying Unit IV, students will be able to:

- Define biodiversity and explain the need for its conservation.

- Identify and define genetic, species and ecosystem diversity.

- Explain the biogeographical classification of India.

- List the values of diversity.

- Describe consumptive use and productive use.

- Identify the social, ethical, aesthetic and optional values of biodiversity.

- Describe biodiversity at the global, national and local levels.

- Define hotspots in diversity and explain why India is a megadiversity nation.

- Identify and describe threats to biodiversity, such as habitat loss, poaching of wildlife, man–wildlife conflicts and list some endangered and endemic species of India.

- Explain conservation of biodiversity in terms of in-situ and ex-situ conservation of biodiversity.

4.1 Biodiversity and its Conservation

4.1.1 Introduction

Biodiversity is the variety and the number of living organisms (both plants and animals) present in the ecosystem. At the 1992 Convention on Biodiversity held in Rio de Janeiro, it was defined as ‘the variability among living organisms from all sources including inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part. This includes diversity within species, between species and of the ecosystem.’

Diversity is a rule of nature and the policy of the natural habitat. So, there is variability (difference) of genes within and between the species and also diversity of ecosystems. It is impossible to have a species with zero diversity.

Food chains that form a food web, link the species to one another. This keeps the energy flowing continuously inside the ecosystem. Any loss in species (biodiversity) means the breaking of a link in the food chain which in turn affects all those who benefit from the chain. Human beings, who are at the bottom of the chain are the ultimate sufferers. Hence, every effort has to be made to conserve biodiversity.

Being a combination of genes, species and the ecosystem itself, biodiversity represents the quality and characteristic features of life in an ecosystem. This diversity can be divided into:

- Genetic diversity.

- Species diversity.

- Ecosystem diversity.

Genetic Diversity

When there is a variation of genes within the same species (single population) and also among geographically separated populations it is called genetic variation. It is responsible not only for the difference in characteristics but also for the adaptation of organisms to a particular habitat or environment. Within the same species, while some individuals are taller than others, some have brown or blue eyes.

A change in external as well as internal factors is responsible for genetic variations. The species that is spread out over a large area interbreeds thereby spreading its genes but the species that is confined to a small area, has a low, very localized gene flow.

According to an estimate, there are 10,000,000,000 different genes distributed all over the biosphere though all of them do not make similar contributions towards genetic diversity.

Species Diversity

This diversity provides a quantitative idea of the number of species and the variety of species present in a particular ecosystem. Table 4.1 gives us the number of various life forms (species) described so far on earth.

Table 4.1 Species Diversity in the Biosphere

| Sl. No. | Life Forms (Species) | No. Described |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virus | 1,000 |

| 2 | Bacteria | 3,060 |

| 3 | Cyanobacteria | 1,700 |

| 4 | Fungi | 28,983 |

| 5 | Algae | 26,900 |

| 6 | Lichens | 18,000 |

| 7 | Bryophytes | 16,000 |

| 8 | Pteridophytes | 11,299 |

| 9 | Gymnosperms | 929 |

| 10 | Dicotyledons | 1,70, 000 |

| 11 | Monocotyledons | 50,000 |

| 12 | Invertebrates | 9,89,761 |

| 13 | Mammals | 4,000 |

| 14 | Other vertebrates | 48,853 |

| 15 | Other forms | 27,400 |

| Grand Total | 13,92,485 |

So far there are approximately 13.92 million species on earth and the expected number is about 25–30 million, with tropical and sub-tropical parts contributing around 70 per cent of the global biodiversity. Presently, about 3,000 scientists are engaged in exploring and identifying these life forms.

Species diversity is the most basic way to keep an account of biodiversity as it includes all forms of life from micro-organisms such as viruses and bacteria to multi-cellular kingdoms of plants, animals, and fungi.

Ecosystem Diversity

A broader scale of biodiversity depicts the differences between different habitats, ecological processes, and the ecosystem in which the species exist. Based on the physical structure and species composition, the ecosystem can be divided into:

- Terrestrial Ecosystems such as forests, grasslands, deserts and so on.

- Aquatic Ecosystems: These are of two types:

- Freshwater, consisting of lotic and lentic.

- Marine, consisting of oceans and estuaries.

- Artificial or Man-made Ecosystem consisting of lakes, croplands and so on.

4.1.2 Biogeographical Classification

The scientific study of the geographic distribution of plants and animals is called biogeography. This science of biodiversity patterns, distribution and abundance of species, population, health and so on, is of utmost importance to us as we depend on plants and animals for food, clothes, shelter, medicines, oxygen, water and energy. For example, people living on islands can understand the importance of the species of a particular community. As per the island biogeography, the number of species on islands of similar habitat and latitudes depends on the size and location of the islands.

The entire biosphere based on oceans, mountains, deserts and so on, can be split into eight distinct biogeographic regions based on the combination of plants, animals, and climate:

- Nearctic region of North America,

- Neotropical region of South America,

- Palearctic region of Eurasia and North America,

- Afrotropical region of India and South East Asia,

- Oriental region of India and South East Asia,

- Australasian region,

- Oceanic region and

- Antarctic region.

In the absence of any precise boundary to demarcate two sub-regions of specific climates and relative isolation, these regions too are further divided into biogeographical sub-regions. For instance, Philippines is a part of the Indo-Malay region which stretches from humid tropical India through the Malay Archipelago to New Guinea.

These sub-divisions are further divided into biogeo zones or biogeographic zones or biomes. Biomes are spatial delineation of the country into contiguous and more or less homogeneous zones where plants and animals live together in related diversity.

With about 8 per cent of biodiversity concentrated in about 2 per cent of the earth’s space, India is one of the 12 megadiversity countries in the world. To ensure proper planning and conservation of the environment at the national, state, and local levels, India needs to be further classified into different biogeographic zones and then into biotic provinces or land regions or ultimately into biomes. The total area of 32, 87, 263 sq km in India has been classified into 10 biogeographical zones listed in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Biogeographic Zones of India

4.1.3 Values of Diversity

Nature gives us sustenance and biological resources form the basis of all life on earth. The fundamental, social, ethical, cultural and economic value of these resources has been recognized in religion, art and literature from the earliest days of recorded history. Thus, conservation of these resources is very essential and has now become a global issue. For conservation of biological resources an economic evaluation of biodiversity is essential. Depending on the economic evaluation different funding agencies such as banks, governments, and so on provide monetary assistance for the conservation of biodiversity. But the hidden cost of loss of biodiversity is very difficult to determine. However, economists and biologists have categorized the values of biodiversity by assessing how people benefit from them. These values are of:

- market-place resources,

- unharvested resources and

- future resources.

The economic values of biodiversity can be categorized as:

- Direct Use Values: These are values directly used by people.

- Indirect Use Values: They provide benefits even if not used by people.

- Social Values: These provide some usable or non-usable benefits in the future.

- Existence (Ethical) Values: These provide benefits in the present and may not benefit our future generations.

Direct Use Values

These are values directly consumed by the people and include food, products for developing pharmaceuticals, for developing and maintaining the genetic basis for agriculture, supporting industry through timber extraction, fisheries, poultry, dairy farming, and so on. Direct values may be of both consumptive and productive use.

Consumptive Use Values: These include food products and fossil fuel (wood) which does not figure in the national or international market but are consumed locally. About 3,000 plant species, 200 of which have been domesticated are used as a food source. Presently, 20 per cent of these plants provide more than 80 per cent of our food. To meet the huge demand breeders opt for the hybrid variety. This variety has better resistance to drought and disease and has wide genetic diversity. Compared to plants, a smaller variety of animals are used by humans for food. However, trees provide 3.8 million cubic meters of food annually by way of fuel, timber or pulp.

Productive Use Values: These are values of products that are harvested from the wild and sold in national and international consumer markets. For instance, many of the raw materials used for drug manufacturing are either plant-based or animal-based. Globally, 3.5 billion people consume herbal medicines. Raw materials for industries such as fibres, resins, dyes, waxes, lubricants, perfumes, pesticides, timber and so on are either plant or animal-based and have a high monetary value in the market. In fact, the cost of the productive use value of biodiversity is constantly rising.

Indirect Use Values

These are as important for the well-being of human beings as are direct values. Indirect Values are obtained without using up the resources and include soil formation and protection, watershed protection, waste disposal, pollination, nutrient cycle, oxygen production, carbon sequestration, control of floods, climate regulations, recreation and eco-tourism, educational and scientific value and environmental monitoring.

Social Values

Aesthetic, recreational, cultural and spiritual, social values are ideals and beliefs which people preach and uphold in order to structure the traditions, institutions and laws of the society they live in. The relationship between human beings and nature and the one between society and nature is very important. These values evolve and undergo changes with changes in circumstances and relationships. There can be a marked difference in landscape and biodiversity preferences according to age, socio-economic factors and cultural and religious influences. The following six values provide a definition of social values:

- Human conquest of nature carries a moral responsibility for the perpetuation of other life forms. (Hornday, 1914)

- Wanton consumption and merciless slaughter of wildlife is uncivilized. (Hornday, 1914)

- Aesthetic and intellectual contemplation of nature is integral to the biological and cultural inheritance of many people. Monuments of nature, great works of art and architecture, should be guarded from ruin. (Conwentz, 1909)

- Healthy ecosystems are necessary to safeguard economic growth, quality livelihoods and social stability. (Ehrlich & Eherlich, 1992; Daily, 1997; Carson, 1999)

- It is prudent to maintain the earth’s genetic library from which society has derived the basis of its agriculture and medicine. (Myers, 1979)

- Society has a moral duty to permit traditional people inhabiting natural landscapes to choose their own destiny in time frames appropriate to their history and culture. (WCED, 1987)

Social movements along with the efforts of non-governmental organizations at the national and international levels, play an important role in the conservation of nature. Today, there is a marked shift towards development. In that context if nature is divided into discrete units and assigned a monetary value it can be treated as a commodity and conservation can be treated as a free market delivery of economic goods and services. The social values in conserving nature can then become more effective.

Aesthetic Values: The use of biodiversity for recreation, scientific investigation, and eco-tourism is also growing rapidly. The fast growing ‘leisure industry’ has now begun to value nature for its aesthetics, and treats it as part of the cultural heritage. People too prefer to visit a reserve forest and enjoy nature-based activities such as hiking, trekking, bird and wildlife watching, fishing and photography. The aesthetic value of our ecosystem contributes to the emotional and spiritual well-being of a highly urbanized population. Partly due to the government’s contribution, eco-tourism contributes financially to conservation. Thus, nature provides opportunities for outdoor recreation to millions of nature lovers if it is conserved. In fact, the travel and tourism economy in India accounts for 5.6 per cent of the total Gross Domestic Product.

Option Values: The potential of a species to provide economic benefits to human beings in the future is called option value. The biotechnologists working towards generating new species to fight and cure deadly diseases such as cancer and AIDS are a fine example of option value.

Existence (Ethical) Values

Unlike the other values, ethical values are an intrinsic part of nature. It is very difficult to quantify their economic value. But, these play a major role in the protection and conservation of biodiversity along with all the other values. All religions, cultures and philosophies, stress on being ethical. The ethical obligations for protecting biodiversity are:

- Protect other species from extinction.

- Do not waste resources.

- Remember that all species are interdependent and have a right to exist.

- People must take responsibility for their actions.

- People must feel responsible towards their future generations.

- Remember that nature has spiritual and aesthetic values that can be transformed into economic values.

- Keep in mind that nature matters to us and so our actions must not harm it.

The ethical values of biodiversity teach us:

- How to improve quality of life.

- How to conserve natural resources.

- How to enrich environmental quality, culture, religion and aesthetics of society.

4.1.4 Hotspots in Diversity

According to British ecologist Norman Myers, certain ecosystems despite their small size account for a high percentage of global biodiversity. Many of these areas also suffer from logging, overexploitation of land due to excessive agriculture, hunting and climatic changes. Myers was the first to devise the concept of biodiversity hotspots so as to identify these areas and preserve the endemic species there.

Biodiversity hotspots are environmental emergency rooms (store houses) of the earth. They are biologically rich areas with a large percentage of endemic species. For example, a terrestrial biodiversity hotspot is based on plant diversity that has:

- At least 0.5 per cent or 1,500 of the world’s 3, 00,000 species of green plants

- Has lost 70 per cent of its primary vegetation.

Coral reefs and multiple taxa (species of coral, snails, lobster and fishes) signify marine hotspots. Most hotspots are found in tropical and sub-tropical areas because warm, moist tropical environments are conducive to the growth and reproduction of the species present there. Species and ecosystem diversity varies with altitude and depth. For instance, the mountainous environment (orobiome) is vertically divided into montana, alpine and nival ecosystems and diversity in the aquatic ecosystem (both marine and freshwater) species decreases as we go deeper. Biodiversity also tends to increase from the Poles to the Equator.

Keeping in mind Myers’ definition of hotspots, biologists have identified areas of high endemism with species richness and labelled them as hotspots. Hotspots are defined as the localized concentration of biodiversity, and are in need of sincere conservation action. Conservation International has identified 25 terrestrial biodiversity hotspots around the world for conservation.

The identified hotspots around the world are:

- Tropical Andes,

- Meso-American forests,

- Caribbean,

- Brazil’s Atlantic forests,

- Choco Darien/Western Ecuador,

- Brazil’s Cerrado,

- Central Chile,

- California Floristic Province,

- Madagascar,

- Eastern Arc and coastal forests of Tanzania/Kenya,

- Western African forest,

- Cape Floristic Province (South Africa),

- Succulent Karoo,

- Mediterranean Basin,

- Caucasus,

- Sunderland,

- Wallace (Eastern Indonesia),

- Philippines,

- Indo-Burma (Eastern Himalayas),

- South-Central China,

- Western Ghats of India and the Island of Sri Lanka,

- South-West Australia,

- New Caledonia,

- New Zealand and

- Polynesia and Micronesia Island complex including Hawaii.

A recent global study conducted over four years, by nearly 400 scientists and other experts has identified nine new hotspots; bringing the total to 34. These new hotspots are home to 75 per cent of the world’s most threatened mammals, birds and amphibians. Originally, these hotspots covered 16 per cent of the earth’s surface which has now reduced to 2.3 per cent due to human encroachment and habitat destruction.

The nine new hotspots are:

- East Melanesian Island,

- Madrean Pine-Oak Woodland on the US-Mexico border,

- Japan,

- Horn of Africa,

- Irano-Anatolian region of Iran and Turkey,

- Mountains of Central Asia,

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany in southern Africa (parts of Mozambique, South Africa and Swaziland),

- Himalayan region and

- Eastern Afro-Montana along the eastern edge of Africa from Saudi Arabia to Zimbabwe.

However, World Wildlife Fund (WWF) replaced the biodiversity concept that Myers had devised in 1977 with the ‘Global 200’ Strategy in 1998. Global 200 expands the conservation priorities to 233 eco-regions, comprising 19 terrestrial, freshwater and marine major habitats thereby covering major biodiversities of the planet.

4.2 India—A Megadiversity Nation

India has a rich heritage of forests, wetlands and marine areas, which range from the temperate forest to coastal land and tropical rain forest to the alpine region. This richness makes it one of the 12 megadiversity nations of the world.

As per the statistics of the Ministry of Environment and Forest, India accounts for 7.31 per cent of the total fauna, and 10.88 per cent of the total flora of the world. It has different biogeorgaphic zones and 25 biotic provinces and also hosts mega fauna such as rhinoceros, tigers, elephants and so on. Table 4.3 gives a clearer picture of the percentage and ranking of India’s biodiversity.

Table 4.3 Comparison between the number of species in India and the World and Percentage and Ranking of India

Of the 75.23 million hectares of forest in India, 40.61 million hectares are classified as reserved and 21.51 million hectares as protected area. This includes over 40 wildlife sanctuaries and 70 national parks spread across 1, 40,000 sq km. The remaining 13.11 million hectare forest area is maintained as unclassified. Marine protected area covers 2, 76,042 hectares, supporting economically valuable ecosystems such as mangroves, estuaries, lagoons and coral reefs.

Over 70 million years ago, India was formed when a giant continent split up, resulting in the formation of Gondwanaland and the southern land mass. India was attached to Africa, Australia and Antarctica. Subsequently, due to tectonic movements, India shifted northward to converge with the northern Eurasian continent across the Equator. When the intervening Tethys Sea started drying up, plants and animals that evolved in Europe and the Far East began migrating to India.

Subsequently, the Himalayas grew to form a natural barrier in the north, along with the three seas – Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean – in the south.

Some of the other prominent features of India as a megadiversity nation are its three important biomes: tropical humid forests, tropical dry deciduous forests and the arid or semi-arid deserts.

India has 25 hotspots mainly in the Western Ghats and the Eastern Himalayas. It ranks seventh in its contribution to world agriculture. India has more than 34,000 cereals and 22,000 pulses in its gene bank.

4.2.1 Endangered and Endemic Species of India

Natural and anthropogenic causes have always remained a great threat to biodiversity. Developmental works are only accelerating habitat loss and pushing wildlife (both fauna and flora) towards extinction (1,000 to 10,000 per year). Based on this, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) has categorized wild flora and fauna into eight categories. The list containing these categories is known as the Red List. These categories are: extinct, extinct in wild, critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, lower-risk, data-deficient and not evaluated. This data, recorded in the Red Data Book is updated every four years. According to the Red Data Book, a threatened species is one whose natural habitat is disturbed. As a result, the species population decreases rapidly and there is a fear that the species may become extinct. As per Schedule I, of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 of India, a species is considered endangered when its number reduces to a critical level. The species is then provided with legal protection. So far, 38 species of birds, 18 of amphibians and reptiles and 81 species of mammals have been labelled endangered in India.

A species faces a very high risk of extinction in the wild when there is a suspected reduction of at least 50 per cent over the last 10 years or three generations, whichever is longer, based on the following:

- direct observation,

- an index of abundance appropriate for the species,

- a decline in area of occupancy,

- extent of occupancy and/or quantity of habitat,

- actual potential levels of exploitation and the effects of introduced species,

- hybridization,

- pathogens,

- pollutants,

- competition or parasites.

Endangered Species of India

Andaman Shrew (Crocidura andamanensis) (endemic to India)

Andaman Spiny Shrew (Crocidura hispida) (endemic to India)

Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus)

Banteng (Bos javanicus)

Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus)

Capped Leaf Monkey (Trachypithecus pileatus)

Chiru (Tibetan Antelope) (Pantholops hodgsonii)

Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus)

Ganges River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica)

Golden Leaf Monkey (Trachypithecus geei)

Hispid Hare (Caprolagus hispidus)

Hoolock Gibbon (Bunopithecus hoolock, previously Hylobates hoolock)

Indian Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis)

Indus River Dolphin (Platanista minor)

Kondana Soft-furred Rat (Millardia Kondana) (endemic to India)

Lion-tailed Macaque (Macaca silenus) (endemic to India)

Markhor (Capra falconeri)

Marsh Mongoose (Herpestes palustris) (endemic to India, it was previously considered to be a sub-species of Herpestes Javanicus)

Nicobar Shrew (crocidura nicobarica) (endemic to India)

Nicobar Tree Shrew (Tupaia nicobarica) (endemic to India)

Nilgiri Tahr (Hemitragus hylocrius) (endemic to India)

Parti-colored Flying Squirrel (Hylopetes alboniger)

Peter’s Tube-nosed Bat (Murina grisea) (endemic to India)

Red Panda (Lesser Panda) (Ailurus fulgens)

Sei Whale (Balaenoptera borealis)

Servant Mouse (Mus famulus) (endemic to India)

Snow Leopard (Uncia uncia)

Tiger (Panthera Tigris)

Wild Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis previously Bubalus arnee)

Woolly Flying Squirrel (Enpetaurus cinereus)

Endemic Species

Species that have very restricted distribution and are found over relatively small ranges are called endemic species. Since their ecological requirements are met over a small area these species remain restricted to a particular area as rare or endemic species.

About 33 per cent plants of the world are endemic to India. North-east India, the Western Ghats, northwestern and eastern Himalayas, a small pocket of the Eastern Ghats and of course Andaman & Nicobar Islands are rich in endemic species. In fact, as per the 1983 Botanical Survey of India, the Andaman & Nicobar Islands boast of at least 220 species of endemic flora in India. Agastyamalai Hills, Silent Valley, New Amarambalam Reserve, Periyar National Park, all the mountains of Western Ghats and eastern and western Himalayas are known for their conservation.

There are 44 endemic species of mammals, confined to a small range within the Indian Territory. The Western Ghats have been identified as the abode of four of these endemic species:

- Lion Tailed Macaque (Macaca Silenus)

- Nilgiri Leaf Monkey (Trachypithecus johnii called Nilgiri Langur by the locals)

- Brown Palm Civet (Paradoxurus Jerdoni)

- Nilgiri Tahr (Hemitragus Hylocrius)

Endemic bird species are not a very common sight in India. About 55 of the endemic bird species can be spotted along the mountain ranges in eastern India. The other places where they can be found are south-west India (the Western Ghats) and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

As for the other animals, the number of endemic reptiles and amphibians in India is high. There are 187 reptiles and 110 amphibians endemic to India. In fact, India is the only country which is abode to eight amphibian genera. The most notable among them is the monotypic Melanobatrachus, which has only one species known only from a few specimens collected in the Annamalai Hills, in 1870.

4.2.2 Hotspots of India

The high endemism of Indian biodiversity is under constant threat. Among the 34 hotspots of the world, two are located in India and they extend to the neighbouring countries. The two hotspots are located in the eastern Himalayas, covering the Indo-Myanmar region and the Western Ghats, extending to Sri Lanka. About 30 per cent of the total flora recorded in the world are endemic to India and are concentrated in these two regions. About 62 per cent of the known amphibian species, reptiles, swallow-tailed butterflies and some mammals are endemic to the Western Ghats.

Eastern Himalayas

The eastern Himalayas include Bhutan, north-eastern India, southern, central and eastern Nepal and Yunan province in South West China. The species geographic distribution shows a distinct growth in the flora and fauna of these areas. The eastern Himalayas have a greater variety of oaks and rhododendrons than the Western Himalayas because of the higher rainfall and warmer conditions in the eastern Himalayas. Many deep, semi-isolated valleys are exceptionally rich in endemic flora. For example, of the 4,250 plant species in Sikkim in an area of 7,298 sq km, 2,550 or 60 per cent are endemic. India has 2,000 or 36 per cent of the endemic plant species out of 5,800, while Nepal has 7,000 of which many overlap with those of India, Bhutan and Yunan. Yunan has 500 endemic plants, nearly 8 per cent while Bhutan has 5,000, which is 15 per cent of the total plant species that are endemic to the eastern Himalayas.

The discovery of a new large mammal Muntiacus gongshanensis and four new genera of flowering plants in South East China have confirmed the findings of a study that said north-east India along with Yunan is an active centre of organic evolution. This hotspot is also home to 163 globally-threatened species, including three of Asia’s largest herbivores – the Asian Elephant (Elephas Maximus), the great One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinocero Unicorn), Wild Water Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis), its largest carnivore, the tiger (Panthera Tigris) and several large birds like vultures, adjutant storks and hornbills.

Earlier, clubbed with the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot, the eastern Himalayan region now stretches across the Indo-Burma hotspot and the Himalayan hotspot. The Himalayan hotspot was identified as a new hotspot in 2005. Table 4.4 lists the biodiversity and endemism of eastern Himalayas.

Table 4.4 Diversity and Endemism of Eastern Himalayas Hotspot

Western Ghats (Southern India) and Sri Lanka

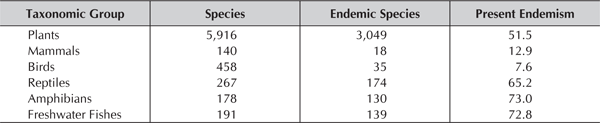

The tropical rain forests of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala in the west and south of India are very rich in biodiversity. In fact, the Western Ghats feature in the 34 hotspots of the world. The two main centres of diversity are Agasthymalai Hills and the Silent Valley/New Ambalam Reserve Basin. The Agasthyamalai Hills in the south harbour, houses the highest level of plant diversity. This hotspot is home to 11,000 animal species. Of the 140 mammal species present, 20 are endemic, the most prominent being the lion-tailed macaque and Asian elephants. Similarly, of the 450 bird species, as many as 35 are endemic. The hotspot also contains 6,000 vascular plant species, of which more than 3,000 (52 per cent) are endemic to the area. Table 4.5 gives a clear picture of the diversity and endemism of the Western Ghats.

Table 4.5 Biodiversity and Endemism of the Western Ghats Hotspot

4.3 Threats to Biodiversity

The human drive for ‘development’, has led him to exploit more natural resources than are actually needed to improve the living conditions. This is responsible for endangering other species of the biosphere. These human actions are beginning to threaten biodiversity. The human urge to transform habitats and exterminate rivals and competitors has led to a lot of harm being caused to all ecosystems and species. Some of the major threats to biodiversity are:

- loss/degradation of habitat,

- overexploitation of resources,

- pollution,

- extinction of species due to aggressive non-native species and

- global environmental changes.

4.3.1 Degradation of Habitat

A habitat is where every living being finds food, water and shelter to survive and a safe place to reproduce and bring up their offspring. So, loss of habitat is actually the greatest threat to the world. As per a global study by IUCN in 2000, 89 per cent of all threatened birds, 83 per cent of all threatened mammals and 91 per cent of all threatened plants have already been affected by loss or degradation of habitat. This can be caused by natural disasters like flood, fire, hurricanes and erosion. The human need for wood, minerals and water (dams) could also be responsible for this loss. Air and water pollution along with global climate changes also affects sensitive species.

Deforestation for agriculture (jhum cultivation), clearing of land for developmental work, overgrazing and so on, are also responsible for fragmenting habitats into small, isolated, scattered populations that are vulnerable to inbreeding, depression, high infant-mortality and susceptible to environmental stochasticity and possible extinction.

Changes in forest composition, quality and habitat-type, lead to a decline in primary food species for wildlife and eventually to loss of habitat. However, statistics show agricultural practices as one of the major causes of loss of habitat.

Table 4.6 Cropland in Million Hectare p.a.

According to a recent estimate, at least 120 out of the 620 living primate species (apes, monkeys, lemurs and others) will become extinct in the wild, in the next 10 to 20 years. Large animals like tigers, mountain gorillas, pandas, Indian lions, tropical orchids and spotted owls often suffer more because they need larger areas for survival. The only species that benefit from human activity are rats, cockroaches, house flinches and so on.

4.3.2 Overexploitation of Resources

Unlimited extraction (through mining, fishing, logging, harvesting and poaching) and development work (human settlement, industry and associated infrastructure) are the major factors that contribute to the overexploitation of resources. As a result of this overexploitation, tigers, giant pandas, black rhinoceros, musk deer, cod and several whale species are on the verge of extinction.

4.3.3 Pollution

Loss of biodiversity due to pollution is very common these days. When we pollute nature with the waste generated by us, only the biodegradable waste gets broken down slowly and gets recycled. But the non-biodegradable or less biodegradable waste remains in the environment and enters our food chain. This waste travels through the food webs, gets biomagnified and reaches the tissues of all living species. These wastes are very toxic and sometimes their toxicity increases with time. A very common example of this is the organic pesticide DDT which affects all types of birds (peacocks, hawks, kites, and so on). Therefore, pollution in various forms is responsible for global climatic changes and for the extinction of most of the species till date.

4.3.4 Extinction of Species due to Aggressive Non-native Species

Despite its importance, this aspect is often overlooked particularly in island areas. When two or more species are inter-dependent or a particular species has strong links with another, the Domino Effect takes place causing extinction of the weaker species. It is the reported cause of extinction of almost 50 per cent species on islands all over the world since 1600 AD.

4.3.5 Global Environmental Change

Scientists feel that 35 per cent of the world’s existing terrestrial habitat may face extinction due to global warming. Global warming is a result of the accumulation of Greenhouse gases. It causes the global environment to change and leads to the extinction of many species which fail to adapt and acclimatize to the changing environmental conditions.

However, poverty, macro-economic policies, international trade factors, policy failures, poor environmental laws or weak enforcement of the same, unsustainable developmental projects and a lack of local control over resources as well as population pressure are some of the underlying causes of biodiversity loss. Increase in the collection of fuel wood, fodder and grazing of animals belonging to local communities also take a toll on the forest and its biodiversity.

4.4 Threats to Indian Biodiversity

With 7.31 per cent species of fauna and 10.78 per cent floral species in the world, India is very rich in biodiversity. It has 89,451 animal species and several floral species, one-third of which are endemic to the country. These species are concentrated in the North East, Western Ghats, North West Himalayas, Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. But today, this rich biodiversity is under severe threat because of:

- loss/degradation of habitat due to agriculture, extraction,

- fragmentation and overexploitation of resources,

- poaching and international trade of wild species and products,

- economic and social causes such as poverty, government policies, environmental laws and enforcement, population pressure and unsustainable development projects and

- deforestation due to the collection of fuel wood, fodder, overgrazing and agriculture.

Hunting and poaching alone are responsible for bringing to the verge of extinction as much as 37 per cent of the birds, 34 per cent of the mammals and 8 per cent of the plants, in addition to many reptiles and fishes. In fact, some animals such as tigers are more in demand than others which leads them to be poached more often.

Islands are particularly susceptible to invasion by alien species. This poses a serious threat to 30 per cent of the birds and 15 per cent of the plant species.

4.4.1 Combating the Problem

The fact that the world has become conscious of the value of, and a threat to, biodiversity was proven when at the International Convention on Biological Diversity at Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the focus was on the sustainable use of the components of biodiversity. It was decided that the strategies for sustainable conservation of biodiversity should be:

- Worldwide reduction of industrial and domestic pollution.

- Controlling overexploitation of natural resources. Bodies such as the International Whaling Commission and Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species (CITES) are already active in this field.

- Agricultural activities with conservation measures should be encouraged. Organic farming, which promotes habitat diversity, should be promoted.

- The government should set up parks and reserves to protect and rehabilitate wildlife and natural vegetation.

- The government should formulate and strictly implement conservation legislations.

- Progress in combating the alarming loss of biodiversity depends not just on the commitment and sacrifices of individuals but also on the actions of the government.

4.4.2 Poaching of Wildlife

Simply put, poaching is an illicit wildlife trade. It is the illegal killing of wildlife for sale in the international trade market. The animals are killed not only for their meat but also for their hides, and different parts of their body that are used as clothing, for food, to make folk medicine, or jewellery or as trophies. Some people poach just for the thrill of it, while others poach for trade. Poachers operate in groups throughout the year and are interested in any marketable animal that is available. Antlers are sold as trophies and are also used in folk medicine. The gall bladder of a bear can bring $18,000 in Asia. Its paws, claws and teeth are used in taxidermy and folk art trade. The horns and skin of a rhinoceros for traditional medicine, tusks of elephants for ivory, eggs from the paddle fish for caviar, musk of the musk deer for perfume, meat of pangolin, the skin, hide and bones of tigers, leopards, deer and bear are all much in demand.

It is the duty of every citizen to stop poaching and conserve wildlife by:

- Trying to identify poaching offences in your area.

- Reporting poaching incidents to the local wildlife enforcement officer, local poaching hotline or to the state level officers.

- Discussing the value of wildlife and threats posed by poaching with your near and dear ones.

- Encouraging effective wildlife legislation.

- Encouraging the publication of articles against poaching, in local newspapers, journals, television and different mass media, distribution of pamphlets or arranging for lectures meant for a variety of audience.

- Refusing to purchase products that you suspect have been illegally obtained from wild animals.

- Improving wildlife law enforcement, including sufficient patrol officers with proper funding, effective penalties and supporting the judicial system.

4.4.3 Elephant Poaching and Ivory Trade

Despite the fact that CITES has banned international trade in ivory (elephant tusks) in 1990 and provided massive funds for the protection of elephants, poaching has continued albeit at a lower rate. As per statistics, between January 1, 2000 and May 21, 2002, more than 5.9 tonnes of ivory, 2,542 tusks and 14,648 pieces of ivory were seized worldwide; all these facts mean that more than 2,000 elephants have been killed.

Over the last 16 years, more than 289 adult elephants have been poached for ivory in Orissa in India. Illegal ivory trade is extremely lucrative. Ivory sells at Rs 12,000 to 15,000 per kg. If the trend continues, Orissa will soon lose its exalted status of being famous for its magnificent elephants since the time of Ashoka, the Great.

CASE STUDY

Tiger Poaching

In 1900, the population of Royal Bengal Tigers in India was 40,000. It came down to 1,800 in 1972 which prompted the Indian government to launch Project Tiger for the conservation of these big cats. As a result, the tiger population increased to 4,200 by the early 1990s. This came down again to 3,500 due to increased habitat loss and poaching besides other reasons. The population of the South Chinese or Indo-Chinese or Sumatran tiger has also reduced and they are close to extinction. The demand for tiger bones and other body parts for use in oriental medicine is also responsible for bringing the tiger to near extinction.

In 1994, trade in tiger parts was banned in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea and most of South East Asia but it is still legal in Japan and North Korea. Medicines containing tiger parts are still used in Canada and the United States. In fact, as per statistics, one tiger per day is poached in India. If the trend persists, this large cat will become extinct in India in the next five to 10 years. In India, the well-organized poachers face little or no opposition at all from ill-equipped, unarmed wardens and rangers. Although a number of legislations have been enacted in India and a good number of tiger reserves have been created; the enactment of the law with such few wardens is very difficult. In India, tiger poaching is rampant in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, West Bengal, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. A tiger cell has been created in Madhya Pradesh with a view to protect the tigers and seize body parts. The largest seizure took place in 1993, in Delhi, when 400 kg of tiger bones, eight skulls, 58 leopard skins and the skin of a number of other animals was seized and taken into custody.

4.5 Man–Wildlife Conflict

When wild animals leave the protected areas (forests) to raid human settlements in search of food and water it gives rise to a conflict between man and wildlife.

The main reason for this conflict is the growing anthropogenic pressure on wildlife habitat which results in:

- Fragmentation and honeycombing of animal habitat.

- Loss of corridors and migratory routes for long-range animals such as elephants, big cats (tigers, leopards, bears) besides others.

- Loss of food and water in their habitat due to the shrinking of forest cover and loss of biodiversity.

When wild animals destroy crops causing economic and food losses to farmers, affect water supplies, kill or injure humans and cause havoc in the lives of human beings, they retaliate by killing the wild animal.

The conflict is fast becoming a critical threat to the survival of many globally endangered species such as the Sumatran tiger (Panthera Tigra Sumatrae), Asian Lion (Panthera Leo Persica), Snow Leopard (Uncia Uncia), Red Colobus Monkey (Procolocus kirkii.) and many more. It has also been observed that the more volatile species are more prone to extinction because of injury and death caused by humans, traffic (road, railway track) or other accidents (for example, falling into traps, wells, poisoning, electric fences and so on).

Considering that this conflict will always remain, strategies are being evolved by government wildlife managers, scientists and local communities, not just for the protection of humans but also for the conservation of biodiversity (wildlife).

This multi-faceted problem can be minimized with good management practices and approaches involving low-cost strategies such as electric fencing, community-based natural resource management schemes, incentives, and insurance programmes along with regulated harvesting and wildlife or human translocation.

Man–Tiger Conflict in Sumatra

A study by Nyphus and Tilson reveals that the man–tiger conflict is more common in intermediate disturbance zones than in high or low disturbance zones. Intermediate disturbance zones are isolated human settlements surrounded by extensive tiger habitats. There are less chances of conflict in logged, degraded and heavily used areas or in and around protected areas where human entry is prohibited by natural barriers or due to the presence of guards. But in Sumatra, tiger attacks have been recorded around different national parks due to the lack of spatial separation. Hence, for their conservation priority should be given to the security of large animals around reserve borders and in buffer zones.

Man–Monkey Conflict in Zanzibar

The farmers in Zanzibar Island consider the Red Colobus Monkey the third most serious vertebrate pest after the medium and large-sized animals, which threaten their crops. The Red Colobus is an endangered species. Only 1,500–2,000 individuals reside on Unguja Island. Although, the farmers feel that consumption of coconuts by the Red Colobus is a threat to the crop yield, the truth quite the contrary. The monkeys prune small and immature coconuts thereby increasing the yield. In fact, they account for a 2.8 per cent increase in potential harvest. Secondly, they are also a source of income through eco-tourism.

Man–Snow Leopard Conflict in India and Mongolia

Conflict between agro-pastoralists and wildlife is increasing day by day in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary in Himachal Pradesh, India. Almost all the livestock deaths are caused by snow leopards. In 1995, snow leopards killed 18 per cent of the total livestock-holding. In retaliation, villagers captured and killed almost all the pups of the Tibetan Wolf in the 1980s. Similar incidents were also noted in Mongolia where economic losses were attributed to the snow leopards and the Tibetan Wolf and the pastoralists killed them in retaliation.

Man–Wildlife Conflict in India

In India, people living in and around the protected areas mainly depend on forest products, agriculture and agro-pasture. As a result, very often man–wildlife conflicts result in crop loss, injury or loss of human life and sometimes the death of wild animals.

About 1,07,770 people live in 117 villages in and around the Sariska Tiger Reserve Project in Rajasthan. Agriculture and rearing livestock are the main sources of livelihood for them. Many species of wild herbivores such as the Nilgai and wild boars are to be blamed for 50 per cent of the damage to their crops while sambar, chital, the common langur, rhesus monkeys and parakeets are blamed for the rest. Wild carnivores such as tigers and leopards are responsible for livestock loss. Tigers prey on big domestic animals like cattle and buffalos while leopards prey on goats, sheep and calves.

Man–Elephant Conflict

Once upon a time the forests of Orissa were home to thousands of elephants. But the establishment of Brutanga Irrigation Project in Nayagarh district, the coming up of a large number of steel and iron projects in Jaipur, Keonjhar and Sundergarh districts, the proposed Vedanta Alumina’s refinery in Kalahandi district, the Hirakud Dam, the Rengali Irrigation Project and thermal power plants at Talcher in Orissa have caused a severe dent to the wildlife population. Owing to severe pressure on their habitat and food loss, elephants are in their worst-ever confrontation with people. Between 1995–1996 and 2003–2004, a total of 259 persons were killed by wild elephants in Orissa.

But in this case, the good news is that people have understood the problem and are cooperating in regenerating forests, especially in the Dhenkanal district of Orissa. Elephants have also begun to move towards the newly generated forests.

Man–Bear Conflict

In 1998–1999 and 2002–2003, bear attacks in the districts of Angul, Rairakhole, Nabarangpur and Baripada claimed 24 lives. In most cases, the bears attacked when people went inside the forest to pick mohua flowers, kendu fruits or honey.

Man–Leopard Conflict

From 1991-1992 to 2003, 78 instances of depredation were noted, most of which occurred in Sundergarh and Athmallik districts of Orissa. Man–leopard conflicts not only cause cattle loss but are also responsible for human injury.

Man–Crocodile Conflict

As per the 2004 census, Bhitarkanika National Park in Orissa is home to 1,358 estuarine crocodiles. Between 1998-1999 and 2002-2003, eight people were killed in crocodile attacks. Most of the killings occurred when victims went to collect prawn seeds from the sanctuary crossing the buffer area.

Measures Taken

To prevent man–wildlife conflicts, elephant-proof trenches are dug and rubble walls and energy fences are erected. Awareness is spread among people through newspapers, electronic media and by the distribution of pamphlets. Anti-depredation committees are formed to keep track of problem animals or groups and inform villagers and forest departments in the case of any approaching emergencies. High intensity focus lights, fire torches, drums and crackers are used to ward-off problem-causing animals from the site to the interiors of the forests. Apart from this, compassionate payments are also made to victims sustaining severe losses.

4.6 Conservation of Biodiversity

Conservation of biodiversity is aimed at the protection, preservation, management or restoration of natural resources such as the forests and their flora, fauna, and water. Thus, biodiversity conservation includes:

- Protection of all critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, rare and other species of life present in the ecosystem.

- Preservation of all varieties of old and new flora, fauna and microbes.

- Protection and preservation of critical habitats, unique ecosystems.

- Regulation of international trade in wildlife.

- Reduction of pollution.

- Increase in public awareness.

Conserving biodiversity becomes a problem when there is lack of resources and a need to use the land for human activities. The term hotspot is used to define regions of high conservation priority with their biodiversity richness and high endemism and a high threat.

Conservation efforts are often focused on a single species. This is called ‘keystone species’ because the idea of conserving one species over others is more appealing. For example, conservation of tigers over say Zayante band-winged grasshoppers is not only more appealing and convincing, but it also attracts more resources, which can be used for the conservation of an endangered habitat.

However, the process of conservation can be broadly divided into two types:

- In-situ Conservation: In this type of conservation, the natural process and its interaction with the habitat as well as with all the elements of biodiversity are conserved. The establishment of protected areas such as national parks, sanctuaries and biosphere reserves is an example of in-situ conservation.

- Ex-situ Conservation: In case of complete degradation of a habitat, in-situ conservation is not possible, as the endangered species need special care. In such cases, the endangered species is removed from the area and kept under total human supervision in places such as zoos, botanical gardens and seed banks. This is called ex-situ conservation.

4.6.1 In-situ Conservation

The basic principle of in-situ conservation is the protection and management of components of biological diversity through a network of protected areas in their natural habitat. In this method, the total ecosystem is protected by eliminating the factors that are harmful to the existence of the species concerned. Not only, do the endangered species benefit from this, but all the constituent species present in that ecosystem benefit as well. In-situ conservation is a cheap, convenient and natural way of conservation. The species are allowed to grow in their own natural habitat with the conservationists playing a supportive role. As the species grow in their natural habitat, they face natural calamities such as rain, floods, droughts and snow, and thereby evolve into better-adapted forms. For this reason, the wild species are more resistant to the prevailing environmental conditions than the domesticated or hybrid varieties.

However, the main disadvantage of in-situ conservation is that it requires a large area for the complete protection of biodiversity. This implies a restriction of human activity and a greater overlap or interaction of wildlife with local residents near a reserve forest. People living on the outskirts of a natural reserve depend on the forest for their livelihood. At present there are 7,000 protected areas, parks, sanctuaries and natural reserves in the world, covering more than 650 million hectares of the earth’s surface, which is about 5 per cent of the total global land area.

National Parks and Sanctuaries

These are small reserves for the protection and conservation of a few species in their habitat. A national park has a well-defined boundary. Sanctuaries do not have a well-defined boundary and tourists are allowed inside a sanctuary.

Natural Reserve or Biosphere Reserve

These are large, protected areas where the entire biotic spectrum of the climatic zone is preserved. These have boundaries properly identified by legislation. Exploitive human activity or tourists are allowed only up to the outskirts of these reserves areas, which are also scientifically managed.

Project Tiger

The tiger is the finest symbol of earth’s natural heritage but tiger sightings these days are very rare in India because of poaching. Tiger poaching is a recurrent problem in countries such as, India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, North Korea, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, Myanmar and Thailand. Almost all the body parts of a tiger are traded for huge amounts of money. Many believe that tigers have healing powers. They believe that tiger bones cure rheumatism, muscular weakness, back pain and enhance longevity. Tiger skins can fetch $1,50,000, the soup made from its penis is said to increase one’s sexual prowess, the whiskers are potent poisons, tiger brain is used to treat acne, tiger tail mixed with soaps cures skin diseases and pills made from its eyes purportedly calms convulsions. Thus a tiger is considered equivalent to a big bag full of money.

Some species of this big cat are already extinct while others are endangered or close to extinction. According to the WWF, tigers are hunted primarily for the use of their body parts in Chinese medicine; these patented Chinese medicines have a huge demand in Asia. Tigers are also poached for souvenirs such as, their skin and mounted heads.

Efforts are being made to preserve this magnificent predator from extinction. Former Indian Prime Minister, the Late Indira Gandhi, launched Project Tiger in 1972, for the conservation and upliftment of the tiger population in India. At present, India has 27 tiger reserves, which extend from the high Himalayan region to the mangrove swamps of the Sundarbans and the thorny scrubs of Rajasthan. Of these 27 tiger reserves, Manas National Park of Assam has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. Table 4.7 gives a detailed list of the tiger reserves in India. However, more wildlife conservation laws and greater awareness among people are still required for the success of Project Tiger.

Table 4.7 Tiger Reserves of India

4.6.2 Ex-situ Conservation

Due to the degradation and fragmentation of habitat, a large number of species are on the verge of becoming extinct. Ex-situ conservation aims at protecting and preserving such endangered species in zoos, nurseries and laboratories. Breeding plants and animals under human care is the strategy employed by ex-situ conservation. Although, earlier it was not practiced for wildlife conservation today with the advancement of science and technology the practice has emerged as a well-defined technology for the purpose. The following are the two main steps for ex-situ conservation:

- Identification of the species to be conserved.

- The selection of method to be followed for its ex-situ conservation.

- Identification of the Species to be conserved: Those species that are at the maximum risk of extinction are chosen for preservation. The life cycle of the species, its degree of specialization, rich location, dispersal ability, adult survival and atrophic status are studied for the final selection.

- Methods for Ex-situ Conservation: From the study on the selected species, the method for its growth, reproduction and survival under ex-situ conservation is decided. The various methods adopted for ex-situ conservation of the critically endangered species are as follows:

- Long-Term Captive Breeding: If the species is being pushed into extinction due to habitat loss or by some adverse external conditions then they are removed from their natural habitat for longterm captive breeding. Captive breeding can increase their population and help the species to survive. Thereafter, as most of these species cannot survive in their wild habitat they are kept in zoos and botanical gardens under proper care.

- Short-Term Propagation and Release: If the population of a particular species decreases suddenly due to some temporary setback then it is removed from its natural habitat, maintained with ex-situ conservation methods, bred and later released into their natural habitat. Ex-situ crocodile conservation is an example of this method.

- Animal Translocation: If the population of a particular species decreases suddenly then some animals of the same species are brought from a similar habitat and released in the less populated area. For example, if the number of male tigers decreases in habitat number one, then male tigers of the same species are brought from some other area and released in this habitat so as to increase the tiger population here. However, the capture, transfer and release of wildlife from one area to another require maintenance of the species in captivity for a short period.

- Animal Reintroduction: When an animal becomes extinct from its natural habitat, attempts are made to reintroduce the species there. For this, newborn animals bred in captivity or animals caught in infancy and kept in captivity for some time then they are selected and released into the habitat from where the original population has disappeared. It is important to rehabilitate the reintroduced species or they too may suffer the same fate as the original species. For this purpose, proper maintenance of the natural habitat and constant observation of the reintroduced species is very important. These days radio collars are used for observation.

The capture, transfer and release of animals from one locality to another is difficult, so special drugs are administered to the target animal from a distance to immobilize the animal. Special emphasis is laid on the nutrition and health care of the animals by administering preventive medicines and systematic vaccinations to them.

Artificial insemination, embryo transfer and cryo-preservation of gametes and embryos are the techniques used to maintain the genetic diversity of nature.

Biosphere Reserves of India

Biosphere reserves are protected areas of representative ecosystems of terrestrial as well as coastal areas. They are internationally recognized under the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme initiated by UNESCO in 1971. A biosphere reserve is aimed at:

- In-situ conservation of biodiversity of natural and semi-natural ecosystems and landscapes.

- Contribution to sustainable economic development of the human population living within and around the biosphere reserve.

- Providing facilities for long-term ecological studies, environmental education, training, and research and monitoring.

Thus, these reserves could serve as a referral system for monitoring and evaluating changes in the natural ecosystem. A biosphere reserve is classified into three zones:

Core Zone: This zone is meant for the conservation of biological diversity and is securely protected. Nondestructive research work and low-impact activities like education and ecotourism can be conducted here.

Buffer zone: This zone surrounds the core zone and is used for cooperative activities such as environmental education, recreation, basic and applied research and so on.

Transition area: It surrounds the buffer zone and may be used for agricultural activities, settlement of local communities, NGOs’, cultural groups and by other stakeholders for economic interests and sustainable development of the area’s resources.

Globally, 425 biosphere reserves have already been established in 95 different countries since 1979.

The Government of India constituted a panel of experts in 1979, to identify potential areas of biosphere reserves under the MAB Programme of UNESCO. The experts identified 14 sites to be declared as biosphere reserves. Of them, 13 sites were declared biosphere reserves in 2005 and later Achanakmar-Amarkantak was declared the 14th biosphere reserve of India. Table 4.8 lists the biosphere reserves of India that have been declared till date.

Table 4.8 List of Biosphere Reserves of India

World Heritage Sites

The World Heritage Site list was established in November 1972 at the 17th General Conference of UNESCO, under the terms of the convention concerning the protection of world culture and natural heritage. The main responsibility of the World heritage committee was to provide technical cooperation under the World Heritage Fund to safeguard these sites. Table 4.9 lists the world heritage sites of India.

Table 4.9 The World Heritage Sites of India (Natural)

| Sl. No. | Name of the site | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kaziranga National Park | Assam |

| 2 | Manas Wildlife Sanctuary | Assam |

| 3 | Keoladeo National Park | Rajasthan |

| 4 | Sundarbans National Park | West Bengal |

| 5 | Nanda Devi National Park | Uttar Pradesh |

Ramsar Sites in India

A close observation of the current list of Ramsar sites in India (Table 4.10) represents only a fraction of the diversity of wetland habitats existing in the country.

Table 4.10 List of Ramsar Sites in India

4.7 Bioprospecting and Biopiracy

Bioprospecting is the collecting, cribbling of biological samples (of plants, animals and micro-organisms) and gathering indigenous knowledge to help in discovering genetic or biochemical resources. The main objective of bioprospecting is the development of new life-saving drugs, crops that provide better economical benefits or industrial products.

Prior to 1992, biological resources were considered the common heritage of mankind. Anybody could collect and carry samples away from the place without permission.

In 1992, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) established the Sovereign National Rights over biological resources. According to this, the biodiversity-rich countries are committed to:

- Conserve biodiversity.

- Develop it for sustainable use.

- Share the benefits resulting from their use.

Thus, the biodiversity rich countries have to not only allow bioprospecting but also be vigilant so that equal benefit is available to the communities that traditionally use the resources, to corporations (usually in developed countries) and to universities collecting the bioresource. Bioprospecting must also obey the national laws and respect the rules of international treaties like:

- Informed consent: The source country must know, what will be done, which benefits will be shared and must give permission for collection.

- Fair agreement on benefits of sharing: Benefits may include support for conservation, research, equipment, technologies, knowledge, transfer, development and royalties.

CASE STUDY

Jeevani Drug Issue

The local Kani tribals in the Thiruvanthapuram district of Kerala, claim that they can live for days together without food and still be able to perform rigorous physical work just by eating a few fruits of a plant named Aarogyapaccha everyday. Scientists from the Tropical Botanic Garden Research Institute (TBGRI) learnt about the use of this plant and carried out a detailed investigation. The findings revealed that the plant is really a source of health and vitality. The leaves of the plant had anti-stress, anti-hepatoxic and immunodulatory/immunorestorative properties. Eventually, the TBGRI scientists prepared the drug Jeevani from Aarogyapaccha and three other medicinal plants. Later, in 1995, a license to manufacture Jeevani was given to Arya Vaidya Pharmacy, Coimbatore for a period of seven years, for a fee of Rs 10 lakh. The Kani tribals were to get 50 per cent of this amount along with 50 per cent royalty obtained by the TBGRI on the sale of the drug. This is bioprospecting in which all the rules set for the purpose are followed.

When bioprospecting ignores all the principles described above it becomes biopiracy. Translational companies race against one another to manufacture pharmaceuticals and agricultural products from the genetic material of medicinal plants and food crops. They also collect micro-organisms, animals and even genes of indigenous people, for their research activities. Thereafter, these companies rush to apply for a patent of the so-called ‘new’ product or technology, so that they can get larger profit by stopping other companies from using the raw material or by selling the technology.

Farmers, indigenous communities and citizen groups protest against these companies being given patent rights because it is the local communities who are responsible for identifying and evolving the use of these biological species (plants, animals, genes and so on). These companies claim exclusive rights to produce and sell the products made by them. Third World communities are afraid that in future they would have to pay a higher price for the material which they had identified and developed. This injustice (biopiracy) is now being fought by farmers, people and public interest groups. Many NGOs such as Rural Agricultural Foundation International (RAFI) and Genetic Resources Action International (GRAIN) have been raising their voice against these unscrupulous companies.

In India, M. D. Nanjundaswamy of the Karnataka Farmers Union is leading farmers against the patenting of seeds, plants and the operations of foreign grain companies in the country. In 1993, half a million farmers rallied in Bangalore to protest against the Uruguay Round Treaty which opened the door to the patenting of genetic materials, seeds and plants. Such agitations have been held in South America, Asia and the Pacific and also at the Beijing UN Women’s Conference where 118 indigenous groups from 27 countries signed a declaration demanding ‘a stop to the patenting of all life forms’ which is ‘the ultimate commodification of life which we hold sacred.’ They demanded that the Human Genome Diversity Project be stopped and patent applications for human genetic materials be rejected.

Patenting of Life

A bacterium that can digest oil has been derived through genetic engineering. Cells from a human spleen have been transplanted in mice that are genetically predisposed to get cancer. These are derived from living organisms and all these have been patented as human inventions. As these inventions affect the society and the life of the owner, the question is how can one get the right to privatize ownership of life? Campaigns have been launched by religious heads and NGOs against the patenting of life.

Biopiracy—the Turmeric Patent

In 1995, two US-based Indians were granted the US patent 5,401,504 on the ‘use of turmeric in wound healing’ both externally and orally. This patent, which was assigned to the University of Mississippi Medical Centre, USA also granted them exclusive right to sell and distribute turmeric.

Turmeric is a tropical herb of East India. Its rhizomes in the powdered form are used as a dye, a cooking ingredient and in a number of medicinal uses, such as a blood purifier, in treating the common cold and an anti-parasite for skin infections. Turmeric has been used in India for thousands of years. Hence, concern grew about the economically and socially damaging impact of this legal biopiracy. Two years later, in 1997, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) filed a complaint challenging the novelty of the University’s discovery. The US patent office investigated the validity of the patent and revoked it in 1997.

Some other examples of US patents related to Asian materials widely known for their medicinal applications are bitter melon from China (Pollack, 1999); products obtained from the neem tree (azadirachta indica) of India, some varieties of chick peas and basmati rice (by Rice tec) some hybrid varieties of Bolivian quinua by the University of Colorado Scientist (Gari, 2000). Similar cases in Amazonian, Andean countries, Meso-America, Africa and Asia have created widespread awareness about the value of genetic resources and the new modes of biopiracy.

SUMMARY

Causes of Biodiversity Loss

Today, the world has become conscious of the value of biodiversity and the threats facing it. The International Convention on Biological Diversity at Rio de Janeiro, in 1992 focused attention on the sustainable use of the components of biodiversity.

Threats to Indian Biodiversity

India is a rich storehouse of biodiversity, with 7.31 per cent of the world’s species of fauna and 10.78 per cent of the species of flora. The country has a total of 89,451 numbers of animal species and several floral species, one-thirds of which are endemic to the country.

Loss and fragmentation of habitat has generated small, scattered and isolated populations. The strategies for sustainable conservation of biodiversity should follow agricultural activities that are coupled with conservation measures.

Poaching of wildlife

Poaching can be simply defined as illicit wildlife trade. It is the illegal killing or taking of any wildlife for sale, in the international trade market.

Man–Wildlife Conflict

The conflict between man and wildlife occurs when wild animals leave the protected areas (forests) to raid human settlements in search of food, water and to migrate long distances or to raid crops. The main cause of man–wildlife conflict is the growing anthropogenic pressure on wildlife habitat. This results in:

- Fragmentation and honeycombing of animal habitats.

- Loss of corridors and migratory routes for long-range animals such as elephants and big cats (tiger, leopard, bear etc.).

- Loss of food and water in their habitat due to shrinkage of forest cover and loss of biodiversity.

Conservation of biodiversity includes measures like protection, preservation, management or restoration of natural resources including all the critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, rare and other species of life present in the ecosystem. Conservation efforts are often focused on a single species called ‘keystone species’ because some species act as the key to the functioning of a habitat and their loss could lead to greater average change in the entire ecosystem. The process of conservation can broadly be divided into two types:

- In-situ Conservation: In this method, the species are allowed to grow in their own natural habitat. In-situ conservation protects the entire ecosystem; hence a large number of species, along with the flag-ship species, are conserved and the food chain and food web remains intact.

- Ex-situ Conservation: Ex-situ conservation aims at the protection and preservation of endangered species away from their natural habitat under human care in zoos, nurseries and laboratories.

National Parks and Sanctuaries

National parks and sanctuaries are small reserves for the protection and conservation of one, two or very few species in their habitat. A national park has a well-defined boundary. Sanctuaries do not have a well-defined boundary and tourists are allowed inside a sanctuary.

Natural Reserve or Biosphere Reserve

These are large protected areas where the entire biotic spectrum of the climatic zone is preserved. These have boundaries properly identified by legislation. Exploitive human activity or tourists are allowed only at the outskirts of these reserve areas which are also scientifically managed. Biosphere reserves are internationally recognized through the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme of UNESCO initiated in 1971.

Project Tiger

Former prime minister of India, Late Indira Gandhi, launched the program in 1972 for conservation and upliftment of the tiger population in India.

World Heritage Sites

The World Heritage Sites list was established under the terms of the Convention concerning the protection of World Culture and Natural Heritage in November 1972 at the 17th General Conference of UNESCO. The main responsibility of the committee is to provide technical cooperation under the World Heritage Fund to safeguard these sites.

Ramsar Sites in India

Ramsar Sites in India represent only a fraction of the diversity of wetland habitats existing in the country.

Bioprospecting and Biopiracy

Bioprospecting is the collecting, cribbling (sieving) of biological samples (of plants, animals, micro-organisms) and gathering indigenous knowledge to help in discovering genetic or biochemical resources.

ESSAY TYPE QUESTIONS

- Define biodiversity. How is it related to the availability of genes, species and ecosystem of a region?

- ‘Biodiversity of a region is the totality of genes, species and ecosystem of the region.’ Explain.

- Write a short note on biogeographic classification of India.

- Justify the status of India as a megadiversity nation.

- What are the values of biodiversity? Differentiate between direct use values and indirect values.

- What are endemic species? Discuss the status of India as the abode of endemic flora and fauna.

- What are the major threats to biodiversity? Discuss.

- Write a note on the cause, effect and combating of the problem of man–wildlife conflict.

- Write a note on efforts taken for biodiversity conservation.

- Differentiate between in-situ and ex-situ conservation principles.

SHORT-ANSWER TYPE QUESTIONS

- What do you mean by the word biodiversity? Why is it necessary to conserve biodiversity?

- Explain the role of biodiversity in genetic variation of species.

- Write a short note on the necessity of biogeographic classification of the biosphere of the earth.

- Name the biogeographical regions of the earth.

- What are values of biodiversity? Write a short note on economic values of biodiversity.

- What is consumptive use value?

- Write the salient points of social use values.

- What are biodiversity hotspots? How many global hotspots are recorded till date?

- Name two hotspots of India. Justify the objective of identifying these areas as biodiversity hotspots.

- What are endemic species? Name some endemic species of India.

- What are the major threats to the biodiversity of India?

- How does one combat the threat to biodiversity?

- What is poaching of wildlife? How can it be controlled?

- Differentiate between bioprospecting and biopiracy?

- Name the biosphere reserves of India. How does it help in conservation of biodiversity?

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS

- The scientific study of the geographic distribution of plants and animals is called

- biodiversity.

- biogeography.

- ecology.

- biology.

- The entire biosphere is distributed into following number of biogeographic regions:

- Six.

- Eight.

- Nine.

- Twelve.

- The total area of India is classified into following number of biogeographical zones:

- Six.

- Eight.

- Nine.

- Ten.

- Biodiversity hotspots are also known as

- evergreen forests of tropic region.

- biologically rich areas with large percentage in endemic species.

- desert areas.

- All of the above.

- Species with very restricted distribution over relatively small ranges is called

- endangered species.

- extinct species.

- endemic species.

- None of the above.

- The major threats to biodiversity is due to

- habitat loss/degradation.

- pollution and global climatic changes.

- extinction of species by aggressive non-native species.

- All of the above.

- Protection and preservation of endangered species away from their natural habitat under human care in zoos, nurseries and laboratories is known as

- in-situ conservation.

- ex-situ conservation.

- biodiversity conservation.

- None of the above.

- Protection of endangered species by preserving the entire ecosystem is known as

- in-situ conservation.

- ex-situ conservation.

- biodiversity conservation.

- None of the above.

- The concept of biodiversity hotspots is given by

- F.P. Odum.

- Norman Myers.

- James Lovelock.

- Rachel Carson.

- Which of the following is an endemic species found in Western Ghats, India?

- Marsh Mongoose.

- Indian Rhinoceros.

- Brown Palmcivet.

- Flying Squirrel.

- Which of the following is not a world heritage site of India?

- Sundarbans National Park.

- Manas Wildlife Sanctuary.

- Simlipal.

- Kaziranga National Park.

- Which of the following is a Ramsar site in India?

- Sambar Lake.

- Dal Lake.

- Ansupa Lake.

- Dimna Lake.

- Which of the following is an in-situ tiger reserves in India?

- Dudhwa.

- Gulf of Myanmar.

- Western Ghats.

- Agasthyamalai.

- Which of the following is not a biosphere reserve of India?

- Sundarbans.

- Great Nicobar.

- Periyar National Park.

- Khangchenzonga.

- Which of the following is a biodiversity hotspot in India?

- Succulent Karoo.

- Mediterranean Basin.

- Sundland.

- Eastern Himalayas.

- Which of the following animals is endemic to India?

- Snow Leopard.

- Blue Whale.

- Asian Elephant.

- Red Colobus Monkey.

- The variety and the numbers of living organisms present in an ecosystem is called