The Complexity of Suicide Motivation

Abstract

The 174 individuals who wrote notes actively sought to express their thoughts, desires, or emotions. They wanted to leave instructions, apologies, and explanations. Those direct communications helped inform us as to what motivated them to take their own lives. There are very different characteristics among and between groups of people who kill themselves. Prevention and intervention must be tailored to fit the groups. We summarize our findings as they represent multiple and complex motivations, and offer a simplified template for understanding motivations and risk factors.

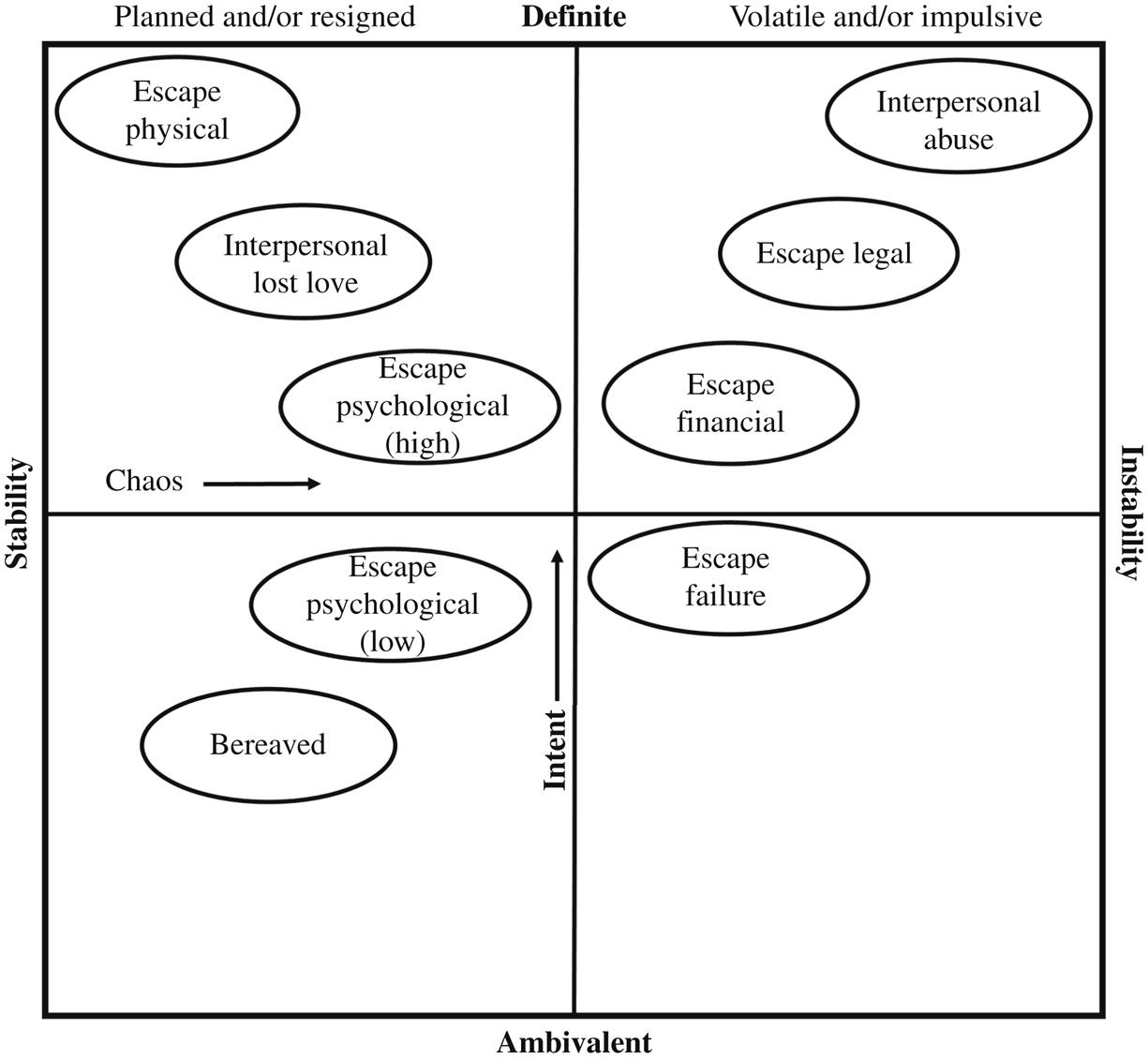

Diagrams help to visually depict the dynamics and characteristics of the groups who committed suicide.

Keywords

Suicide patterns; interpersonal relationships; escape; failure; grief; legal; financial; chaos; intent

In Chapter 2, Findings, Chapter 3, Suicide Motivated by Interpersonal Relationships, Chapter 4, Escape as a Motivation for Suicide, and Chapter 5, Grief and Failure, we examined what motivated individuals to take their own lives. The 174 individuals who wrote notes actively sought to express their thoughts, desires, or emotions. They wanted to leave instructions, apologies, and explanations. Those direct communications helped inform us as to what motivated them to take their own lives. There are other forms of communication that also reveal much about motivations for suicide for note writers and for those who left no note. These communications are the actions of the dead. What they did and how they did it, in conjunction with their written words, create a clearer picture of modern suicide, despite its complexity.

A motivation is what impels the person to commit suicide; a risk factor is a common denominator among those who commit suicide. Thus, financial difficulties may be a motivation; bankruptcy may be a risk factor. In the psychological, psychiatric, and sociological literature, motivation has been the biggest question for researchers hoping to explain suicide, while risk factors have been the focus of prevention and intervention. It is imperative to understand that these are relational, and that any suicide is a complex intertwining of both motivation and risk factors, as well as mental state.

Two main reasons for committing suicide emerged from our data, with a vast majority—approximately 95%—doing so because of interpersonal relationships gone awry or because of a desire to escape something. While a few other motivations such as grief or failure appeared, these were uncommon. But there were other patterns that appeared across motivational categories that related to behavior. We then wondered if effective intervention and prevention might depend on the patterns we found.

Chaos in Life and Intent to Die

We found we could divide suicides across two dimensions, chaos in life and intent to die. Patterns of impulsivity and volatility (chaos) represented one dimension. Individuals were on a continuum from high to low chaos. For example, those in the interpersonally abusive relationship group, those escaping multiple problems, and those escaping legal or financial problems had a high amount of chaos in their lives, while those who were bereaved or escaping physical pain had a low amount of chaos in their lives.

The second dimension was intent, demonstrated by the level of lethality in the method used to kill themselves, as well as in their expressed sentiments if they wrote notes and in their aggressive or passive behaviors. For example, those escaping physical pain or in abusive relationships had a high predilection for death and tried to ensure lethality through the choices they made. Conversely, there were other groups that showed patterns of ambivalence and uncertainty about their suicides. Those who suffered psychological pain, grief, and failure felt despair and resignation, but their behaviors suggest that, as a group, they were less determined to end their lives. If we combine the dimensions, four quadrants emerge (Fig. 6.1).

The diagram in the figure shows four quadrants. In the upper left quadrant are the motivation groups that showed a strong desire to die, based on lethality, words and behaviors, and planned their deaths. Those who wanted to escape physical pain, e.g., had relatively stable lives. They were simply in terrible pain. Had they not been physically ill and unable to cope with the illness, it is unlikely many, if any, of them would have killed themselves. Thus, they are placed on the far end of the chaos line, nearest to stability, but high on the intent line. Their high use of guns (80%) and the content of their notes indicate they definitely wanted their lives to end. In the middle of the upper left are those in interpersonal relationships who lost love or had unrequited love. They experienced some chaos as a result of their loss and so are closer to the center on the chaos line, but they also often planned their suicides and were not as impulsive. They did, however, want to die and chose guns and hanging. Most of this group shot themselves in the head, indicating little ambivalence. Closer to the center, but still in the upper left quadrant, were those in the escape psychological group who had a higher intent to die, but who were otherwise similar to the others in the same quadrant. They were as a group living somewhat chaotic lives, usually because of their mental illness, but were not otherwise extremely volatile or impulsive.

In the upper right quadrant, highest on the intent scale and highest on the chaos scale are those in abusive interpersonal relationships. These people were definite about their desire to die, and they often killed themselves with little, if any, planning. Those escaping legal problems shared the impulsivity and instability of those in abusive relationships. Closer to the center, with less chaos but with high intent, were those escaping financial problems. This quadrant represents the highest usage of guns and violence towards others. In many ways life had spiraled out of control for the individuals in this quadrant.

In the lower right quadrant is only one group, failure. These individuals often spent a long time thinking about what they believed were their messed-up lives, and when they decided to die, they had given it considerable thought. They had not necessarily planned their actual deaths a long time in advance, though, and they used guns much less often than those in other categories. They chose asphyxia more often, and their words often betrayed regret that they were unable to do better in life. Their lives were chaotic, to a degree, because they had multiple difficulties and felt a lot of emotion, but they were not the most volatile.

The lower left quadrant represents the two groups that demonstrated the most ambivalence about wanting to die and who had the least amount of chaos in their lives. In the case of the bereaved, they are close to the stability line. Grief unhinged them and made life unbearable, but in most other ways their lives were stable. If it were not for the death of their loved ones, they probably would not have wanted to die. Among those escaping psychological pain, there was less frequent use of the most lethal means but often there had been multiple attempts or a history of suicidal ideation. They are near the center. Their deaths were not mere accidents, but the pain and instability they felt was pronounced.

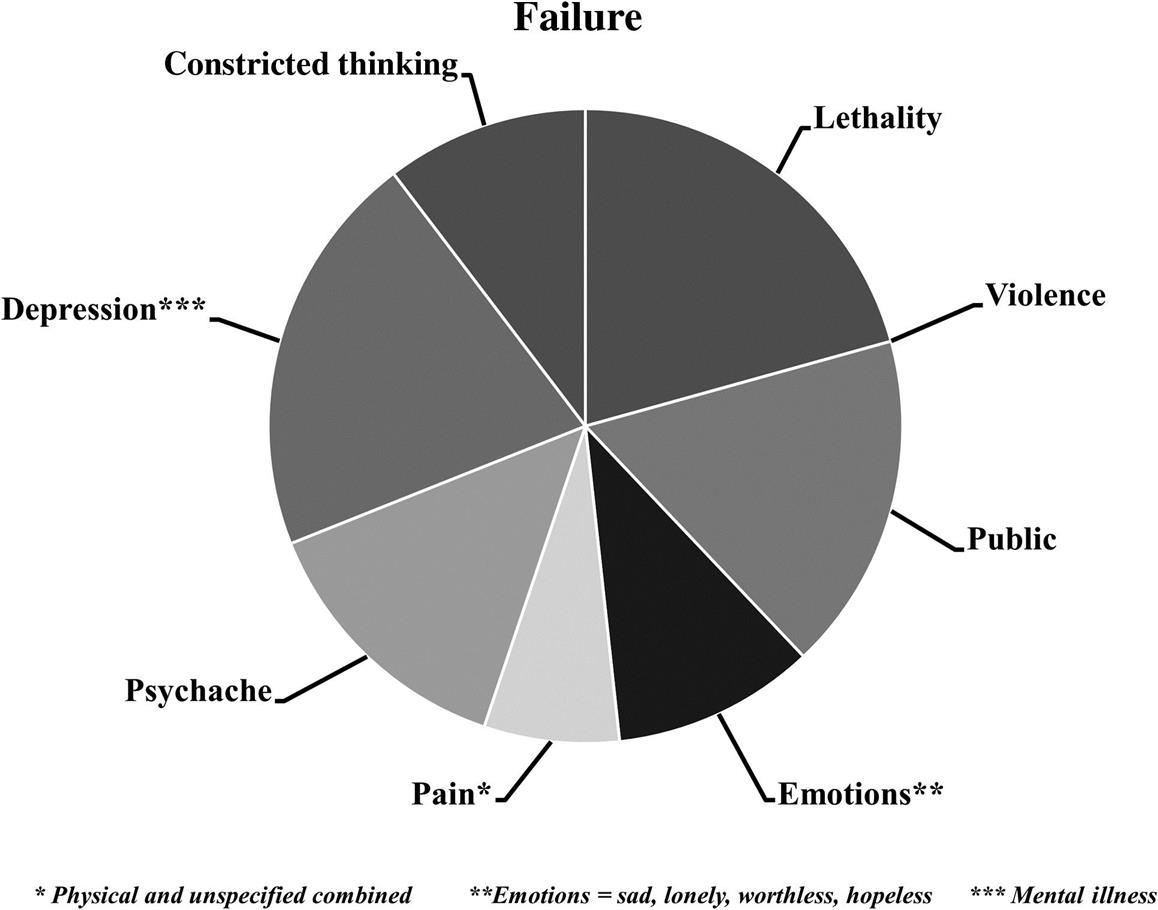

Below we will examine and discuss some of the qualities that the various groups have and theories that may help interpret how those qualities relate to suicide. We have included figures, in the form of circles divided by characteristics, to show group composite images with the most noticeable qualities appearing in the diagram. The circles show the relative importance each quality played in making up the group’s dynamic based on comparative percentages.

Interpersonal Relationships and Gender Dynamics

Men made up the overwhelming majority of suicide victims (82–91%) in every category we examined, although the percentage was lower for those who wished to escape psychological pain (68%) and those who were grieving (68%). Of all those who suffered from unrequited or lost love or who were in abusive relationships, nine out of ten were men. It was men, overwhelmingly, who wanted to escape physical pain, legal entanglements, financial problems, and psychological pain.

The statistics paint a picture of male suicide that is quite striking. In popular culture, we often caricature men as unable to function well in intimate relationships, but for a significant group of men, this is no laughing matter. In matters of love, loss and intimate conflict, some men will take their own lives. But which men? There were two theories of masculinity articulated in the late 20th century that explored men’s power and privilege, or lack of it, in their cultural contexts. Hegemonic masculinity and hypermasculinity explained how men gained and maintained power over other men and women, on the one hand, and defined manliness on the other (Hooper, 2012). The two can also work in tandem, and they may explain the high rate of suicide among men.

Hegemonic masculinity refers to a social construction of power in which men who embody the norm of masculinity, whatever that is for a particular culture, establish and keep power over others (Hooper, 2012). In other words, if men are supposed to be heads of households and breadwinners, there will be a range of masculinities on a continuum that will incorporate or reject those qualities. A very hegemonic man will perhaps be the sole breadwinner or at least the top earner in the household; he may be the disciplinarian in the family, the keeper of the finances, the one who controls the way the household works. A less hegemonic man may cede some control of those things to his partner/spouse. On this continuum at the other end, one may find men who have no interest in being the breadwinner, who enjoy childcare, and who leave the finances to the spouse.

Manliness is not an immutable or unchangeable trait. Among some classes and subcultures in America, for instance, men who are comfortable outside of traditional gender roles and who are inclusive and nurturing are considered more manly and desirable than those who have physical prowess or who exhibit a desire to dominate others. In a country as diverse and as large as the United States, manliness traits can be exactly the opposite among different classes, geographic regions, or racial or ethnic groups. Attitudes about manliness and masculinity affect more than personality. They can help or impede one’s path through life. Certain constructs of masculinity are harmful to men’s health if men will not use services, especially medical or psychological, out of a belief that to do so is weak. Hegemonic masculinity can have some positive elements. These men often feel a great sense of responsibility toward others and will often pitch in to help others, but in some instances this can take a negative turn, if men believe they cannot fulfill those responsibilities or that others will be better off without them (Southworth, 2016). In extreme cases, men who place a high value on being “the family man,” whose identities are completely intertwined with their families, and then who cannot withstand the pressures, often financial but also interpersonal, can go on to commit familicide (Auchter, 2010).

Men who are hypermasculine believe manliness is characterized by violence, risk-taking, endurance of pain, and demonstrated superiority over women. According to both Schneidman (1957) and Joiner (2005), as well as other theorists, to die by suicide a person must be able to overcome the natural fear of death and be willing to endure its pain. Hypermasculine men already see fear of death as unmanly; they are likely to be involved in activities that involve pain, such as contact sports, and they are often involved in domestic violence. Inflicting pain is something they have become accustomed to. Their own masculine gender norms might make them especially susceptible to suicide. Moreover, hypermasculine men often think that talking about or expressing one’s feelings is unmanly, so they are unlikely to be able to resolve problems, communicate their distress or ask for help. Just as German men were the immigrants most likely to kill themselves in the early 20th-century United States because of their emotional reserve and lack of cultural rituals to help them assimilate, modern men in hypermasculine subcultures are at risk. Studies have shown that hypermasculine men exhibited depression, psychological distress, and some suicidal ideation, whether they were straight or gay, black or white, or young or old (Fischgrund, Halkitis, & Carroll, 2012; Granato, Smith, & Selwyn, 2015).

Moreover, in our suicide data, the second and third highest use of guns occurred in the men who were in the abusive interpersonal relationship group (69%) and the unrequited or lost love group (52%), respectively. The CDC found that 55.4% of all male suicide victims used guns to kill themselves, and we found 51% did (CDC, 2016). The CDC also noted, however, that the number of men using guns had declined since 1991, when it was 61.7%. It may be that hypermasculinity and hegemonic masculinity, with their attendant violent or dominant behavior, are in decline (Curtin, Warner, & Hedegaard, 2016). Men’s beliefs about masculinity, and the behavior rooted in that mentality, may be directly related to suicidal behavior. It is also possible for women to have traits that are associated with hegemonic masculinity or hypermasculinity, because these traits are personality characteristics across the gender spectrum. Women can be high risk takers, dominant over other women and men, and violent.

Stallones, Doenges, Dik, and Valley (2013) studied suicide in Colorado from 2004 to 2005 and found that men who worked in farming, fishing, and forestry (475.6 per 100,000) had the highest age-adjusted suicide rates, and a higher number used firearms (50.18 per 100,000). Among women, workers with the highest suicide rates were in construction and extraction (134.3 per 100,000), and in those occupations, most people died by hanging, suffocation, or strangulation. Roberts, Jaremin, and Lloyd (2013) found that in Britain there was a high rate of suicide among farmers, coal miners, seafarers, construction workers, and other manual trades. These were not the only occupations with high risk. Access to the means to kill oneself also explains high suicide rates in some professions (doctors, pharmacists, veterinarians). Occupations with greater numbers of suicide changed from the 1970s to the 2000s, from professionals and farmers to all manual occupations, largely because efforts at prevention had been directed at occupations with high risk in the past (Roberts et al., 2013).

Men who are hypermasculine or who accept a patriarchal, hegemonic masculinity as the normative standard are not necessarily “he-men” in the physical sense. Their physical appearance can be of any body type. Much more significant are attitudes and behaviors that subscribe to certain values: extreme stoicism in the face of pain, perhaps an overdeveloped sense of duty and responsibility, and a willingness to take extreme risks. While many psychologically healthy men are not ones to bare their souls, are loyal and responsible, and enjoy sports or other activities with some risk involved, hypermasculine and hegemonic masculine men will be on the far end of the masculine spectrum and will overvalue these qualities. Hypermasculine men also will exhibit violent behaviors. The men and women who share these traits or who value behaviors associated with the traits may be at more risk of suicide, especially if they are involved in relationships that have turned abusive.

Abusive Relationships

One winter night a 32-year-old white man was sitting in jail on a domestic violence charge. A little after 11 p.m. he was discovered in his cell hanging by a sheet. Not long before Valentine’s Day, a 42-year-old white man hanged himself after he and his wife had a domestic argument. One spring evening a 38-year-old black man jumped from a highway overpass after being involved in a domestic violence incident in his home. One autumn day a 34-year-old white female, who had been incarcerated for domestic violence, hanged herself in her cell.

Every day of every year in all seasons there is a suicide related to domestic violence. Karch et al. (2009) estimate as many as 30% of all suicides may be related to domestic violence.

Interpersonal violence, most of which is domestic violence, is by its nature an event that can turn lethal. In 2013, homicide was the second leading cause of death for both white and black females between the ages of 15–24, the fourth leading cause of death for black women between the ages of 25–34, and the fifth leading cause of death for white women aged 25–34 (CDC, 2014). Nearly 12,000 people in the United States were murdered in intimate partner homicides by current or former male partners between 2000 and 2011. Twenty percent of domestic violence homicides were not intimate partners themselves, but family members, friends, neighbors, persons who intervened, law enforcement responders, or bystanders. Seventy-two percent of all murder-suicides involve an intimate partner; 94% of the homicide victims of these murder-suicides are female (CDC, 2014). Not all of the deaths that result, though, are murder victims. Many of those who die as a result of domestic or interpersonal violence in their lives die by their own hand. Over one-third of the men in our sample who committed suicide in interpersonally abusive relationships also killed someone else.

The men who killed themselves in interpersonal violence situations were generally young to early middle-aged. They were usually physically healthy and were at a time in their lives when they should have been at the peak of their earning opportunities. They were at the age to be raising children, if they so chose. Yet something went terribly wrong for these men.

As our findings showed, they mostly used guns and frequently they committed the act in front of someone else. Most often it was at home, but it is striking how many were elsewhere. Only one other group, those in legal entanglements, killed themselves less often at home, and that was because they were either in jail or sometimes fleeing police. In many cases, the men chose public places for their suicides and chose not to die alone. Two-thirds had been cited for previous domestic violence. The intermingling of public demonstration with private, intimate violence characterized the interpersonally abusive relationship group more than any other, although those escaping from multiple problems had some similar public expression of their private pain. They were trying to communicate, but less through words and more through actions.

These were men who had never expressed any suicidal ideation before their suicides and only 20% had been diagnosed with psychological illness. They were not seeking help for their problems from professionals. In their final notes some of them articulated their psychological pain, but a large proportion could only say they were in some unspecified pain. They hurt but did not, perhaps could not, say why. Violence is a reaction toward a source that is causing pain. It can be directed outwardly or inwardly. Those who act violently in their interpersonal relationships believe someone close to them is causing them pain and deserves punishment. They are either unable to express it verbally or words provide insufficient relief.

While the interpersonally abusive relationship group was more impulsive than other groups, occasionally there was some planning. It was often shorter than those in psychological pain or other categories. Their notes and behavior, when interpreted together, reveal patterns of emotion and thought. Fig. 6.2 represents the dominant characteristics of the group.

The most noticeable emotion they never acknowledged was their anger, which was explosive. They did not feel shame or sadness, and they never felt they were worthless or failures. People failed them, not the other way around. They blamed others, not themselves. They felt no guilt. They wrote about joy, hopelessness, tiredness, loneliness, their love for others, and being loved by others, but as they did so, seething underneath was anger. Love and anger were so balled up together, one articulated in words, the other in violent action, that they were nearly synonymous. Sometimes these individuals did extend an apology for killing themselves, either generally or to another person, but usually not to the person at whom their anger (and their love) was directed. The men in the group appear to have been highly certain of themselves, given what they were about to do, and so it is perhaps not surprising to find tunnel vision and dichotomous thinking. It was all or nothing for them.

This way of thinking about love is often something romanticized in literature, movies, television, and music. Both men and women may internalize the message that love at its most passionate is violent. That passionate love is also one aspect of their lives that many people do feel entitled to, even when they may not feel entitled to much else. “Don’t let anyone ever make you feel like you don’t deserve what you want,” Heath Ledger’s character resolved in 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), a modern remake of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, in which a man makes a noncompliant, rather unpleasant (“bitchy”) woman become his subservient, sweet lover. Even in movies with a healthier message about love, the idea that one should not be able to live without a particular person is ubiquitous. “I didn’t come back to tell you that I can’t live without you,” Jennifer Aniston’s character in Rumor Has It (2005) tells her boyfriend. “I can live without you. I just don’t want to.” In movies like Ghost (1990) or Wuthering Heights (1939, 1970 (in this version, Heathcliff kills himself), 1992, 2012) love persists beyond the grave. Popular media are not responsible for making people think a certain way. In many ways, they reflect what people already think, but they then reinforce the message that relationships are eternal, even if someone dies. When people in an abusive relationship internalize the message that passionate love means conflict, they are often supported in that belief by their social circle. Beres (1999) referred to this as the “subtle romanticization of control” (p. 195). Some of the men in the interpersonally abusive relationship group believed they would be reunited with their intimate partners after death.

A Comparison of Interpersonal Relationships

Men in the unrequited or lost love group (Fig. 6.3) shared many of the characteristics with the abusive group, but they expressed more ambivalence about death and had a greater sense of blameworthiness. Both groups mentioned forgiveness, but the abusive group mentioned it almost twice as much as the unrequited love group, usually to ask for forgiveness from a person other than their intimate partner. They had similar contricted thinking patterns, but more of the men in the unrequited love group had had suicidal ideation prior to the suicide attempt that ended their lives, and they suffered more from depression.

Unrequited love can sound like an old-fashioned phrase, but it is a problem that many people in contemporary society face and struggle with. The pain is quite real. Research demonstrates that people feel an emotional wound in the same way as they feel physical injury. A “broken heart” can feel exactly like that. Kross, Egner, Ochsner, Hirsch, and Downey (2007) found that emotional pain activates the same part of one’s brain as physical pain. Baumeister, Wotman, and Stillwell (1993) estimated that 98% of people have suffered from unrequited love or lost love at one time or another. As a result the person feels sad, lonely and hopeless, as well as ashamed. The persistence of these feelings distinguishes the people in the unrequited love group from other people and from individuals in the abusive group. Those who experience unrequited love, while distinguishable from those in interpersonally abusive relationships, are not wholly dissimilar from them. While physical abuse may not be present, or is present to a lesser extent, the men who experience unrequited love can be emotionally abusive, controlling or manipulative.

The suicides in the physically abusive group were not done quietly. In one case, after having a fight with his wife, a man locked himself in a camper on his property. The police had been called, and upon arriving they asked the man to come out. He refused, so the police obtained a key and unlocked the door. As they began to enter, the man took a fire extinguisher and sprayed the police, throwing it at them to keep them out of the camper. The police used mace against the man. He then grabbed two knives and started toward the police officers. They backed away and the man began to stab himself. He closed the camper door. When the officers finally got back in, the man had stabbed himself in the chest with two different four-inch blades a total of ten times. Many of these cases had elements of graphic violence and were terrifying to the witnesses.

When Oliffe et al. (2014) studied murder-suicide, they concluded that hegemonic masculinities, which value power and aggression, were implicated in the majority of cases. Among the domestic violence cases, these men had “failed to gain or sustain” their dominance over the family or establish themselves as financial breadwinners according to the masculine norms in their communities. In the workplace and school shooting cases that were also examined in that study, problems with masculinity were present.

Intimate partner violence is a problem for women that transcends all races and socioeconomic statuses, but not all women have the same experience. While 82% of the suicide victims in this group were white, 18% were not. Thirty-nine percent had legal problems. We must look to one other category to get a clearer picture; the other category which had the highest percentage of nonwhite suicides was those escaping legal entanglements. African-American men are hardly present at all in some groups, like those escaping physical pain, but in the group of interpersonally abusive suicides and legal entanglements they comprise not quite 18%. The literature also documents that interpersonal violence has a higher impact on African-American women than on white women; African-American women were assaulted by partners at a rate 35% higher than white women (Taft, Bryant-Davis, Woodward, Tillman, & Torres, 2009).

African-American men have been the hardest hit by the rise in mass incarceration over the last 30 years. It is also a community affected disproportionately by unemployment and poverty. There is high religiosity among African Americans, but these religions, Christianity and Islam, tend to be patriarchal. Indeed, a higher emphasis may be placed on the role of men in the family and community, because of a long history of white oppression that specifically denied such power to black men. During slavery, enslaved men could not be married to their partners and had no control over their children, who could be sold away from their parents. After slavery ended, black men often embraced patriarchal values and reasserted their manhood by reclaiming control over their families. Black men in the United States traditionally subscribe to hegemonic masculinity (Hooks, 2004). The relatively high presence of black men among suicide victims in the interpersonally abusive group compared to their presence in other groups is thus not surprising. This group’s close links to those escaping legal entanglements, both in racial makeup and the presence of hegemonic masculinity and hypermasculinity, means that black men in these categories are at a higher risk for suicide than they are across all other categories, and intervention and prevention need to be afforded to these men.

There is no doubt that hegemonic masculinity and hypermasculinity are problems for men of both races. While it would be too much to say that these theories of masculinity explain suicide in the interpersonal relationships category, there is evidence to suggest they played a role in many if not most of the cases we examined. We are not saying that men need to be more like women. There are already more versions of what it means to be a man, and what it means to be manly, that run counter to the hegemonic narrative. The Good Men Project, e.g., is a social media and website presence that invites men to share their experiences and to read about manhood and fatherhood in ways that are supportive and positive (The Good Men Project, 2016). Founded in 2009 by Tom Matlack and James Houghton, the Good Men Project aims to be a “national conversation” about masculinity and men’s experiences. Orienting men, especially young men, to that conversation is an important first step in making them healthier psychologically.

Not all men who commit suicide, and certainly not all women, fit into classifications of hypermasculinity or hegemonic masculinity. While men’s preponderance in a motivational category like interpersonal relationships is firmly established (Van Orden et al., 2010), it is less clear what type of man or woman commits suicide to escape, or whether gender or race matters at all in this category.

Attitudes Toward Death

While those who committed suicide to escape were also predominantly white men, gender, and race intersected in noticeable ways. White men made up the majority of those who wanted to escape, but women were present to a larger degree than they were in other categories, such as those who wanted to escape psychological pain (32%) and those who were escaping multiple things (18%). African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities (almost all of whom were men) were overrepresented in those escaping legal entanglements (18%). It is important to recognize this difference, because these are the escape categories that represent the greatest risk for nonwhites and women. It is also important to look at categories in which whites were almost exclusively at risk, like those escaping physical pain.

All but 3% of the 119 people in our study who killed themselves to escape physical pain were white. At first that number may not seem extraordinary; white men are the majority in every category. However, it signifies that there is a very different attitude about end-of-life issues between whites and blacks. A study on black and white attitudes towards physician-assisted suicide demonstrates different belief systems between the two races about the end of life and may indicate attitudes that factor into suicide (Lichtenstein, Alcser, Corning, Bachman, & Doukas, 1997). For instance, blacks prefer aggressive medical intervention to preserve life in cases that might be fatal far more than whites (Lichtenstein et al., 1997), but they will not use palliative care or hospice facilities where patients go to die (Winston, Leshner, Kramer, & Allen, 2005). Furthermore, whites historically have made up a higher percentage of those who supported physician-assisted suicide since the question was first researched. Over the decades, a gap of nearly 20 percentage points on acceptance of physician-assisted suicide persisted between whites and blacks even as support for it rose in both groups (Lichtenstein et al., 1997).

In order to understand why the gaps existed, Lichtenstein et al. (1997) examined differences in religious beliefs and religiosity between blacks and whites, and found that religiosity was the strongest predictor of lack of support for physician-assisted suicide. The African-American religious community’s belief in preserving life is particularly strong regardless of denomination. Almost all black churches are evangelical, espousing an often fundamentalist interpretation of the ten commandments. Lichtenstein et al. also found that African Americans have a greater distrust of the medical community, in part because of the infamous and well-known syphilis experiments on black men at the Tuskegee Institute in the mid-20th century. The underutilization of end-of-life and palliative care has been attributed in part to the incompatibility between the hospice philosophy of accepting death when cure is no longer possible and African-American religious, spiritual, and cultural beliefs as well as distrust of the medical establishment (Winston et al., 2005). Previous research on African-American suicide revealed that pastors in black churches universally discouraged and condemned suicide even as a means to escape pain from a terminal illness (Early, 1992).

It would be incorrect to suggest that whites lack religiosity or do not take religious beliefs seriously, but differences in church culture may have a bearing on their willingness to commit suicide to end physical pain. Evangelical Protestant churches dominate the United States (25.4%) and Ohio (29%). Yet 22% of people in Ohio are unaffiliated with any religion, and only 67% of Ohioans believe in God with certainty. A slight majority of Ohioans (56%) think religion is important to their daily lives. Perhaps most significantly, 58% never participate in studying anything about their religion (Pew Research Center (Pew Forum), 2016a,b). They lack knowledge of scripture or doctrine, and thus may be unaware of church teachings on suicide. Could differences in religiosity between whites and blacks, as well as differences in attitudes toward end of life issues, explain the whiteness of the escape from physical pain group?

There is evidence, though not conclusive, that religious affiliation, devotional practice (piety) and belief can have a positive effect on mental well-being, though to what degree and for whom is debated. Ellison (1995) examined other research on southern blacks to see if black churches had an impact on depression, which is the mental illness most associated with suicide. According to Ellison, researchers have found that both public and private religious involvement appear to be more important for holding depression at bay for blacks than for whites. Public religious activities help with social integration and with social status. Since blacks have had fewer opportunities for both of those things in secular institutions, the black churches have played a significant role. Also, black congregations sponsor more social service programs than most white churches and disseminate more information related to health and crisis intervention (Ellison, 2015). We can’t know for certain if any of the people in our study were churchgoers or what their personal religion practices and beliefs were, but if blacks and whites in Ohio are similar to those in other states, then understanding the role of religion in helping depression can benefit both groups.

The Pew Research Center (Pew Forum, 2016a,b) reported that 32% of Ohioans had very clear ideas about what is right and wrong, while 66% thought right and wrong depended on the situation. Pew also found that 77% expressed a belief in heaven, slightly higher than the national average of 72%, while 17% did not and 5% were unsure; 63% believed in hell. If those escaping physical pain represent a cross-section of white adults in middle America, and there is evidence to think they do, they may have been among the growing number of white Americans who see no moral or ethical impediment to suicide when it is done to end physical pain (Fig. 6.4).

Effect of Pain

Those escaping physical pain wanted very much to die. They chose highly lethal means, such as guns, and they stayed home where they had privacy. They made sure they were alone. They did not appear to want to be saved from death. Yet we cannot dismiss their suicides as simply the most rational choice. In some instances that might have been true, but much could have been done to make these lives worth living in the time they would have had left had they not killed themselves. Greater access to medical and psychological care, especially on weekends, could have helped some of the victims in our group. Better pain management might have helped those with chronic but not fatal illnesses. More attention on the part of family and friends to remove firearms possibly could have prevented some of these suicides. Communal living situations in which there was less isolation might also have obviated the suicidal situation. These deaths were motivated almost solely by a desire to alleviate physical pain, but in these cases medical, psychological and perhaps even familial resources often failed. The reasons for those failures are complicated, and frequently have to do with funding, and other issues we will discuss in Chapter 10, Conclusions and Implications. A well-planned, well-funded effort to help prevent suicide among the sick and elderly may save lives—lives worth living.

While little ambivalence may have existed for those who wanted to escape physical pain, that was not true of those wishing to escape psychological pain. That group can be split in two—high and low intent—because nearly half (low) chose methods that were less lethal, such as overdose or carbon monoxide poisoning, and reflected more ambivalence in their notes and behavior than the other half (high), who chose guns or asphyxiation by hanging. More specifically, overall 23% died by overdose, 7% by carbon monoxide, 3% using an unknown means, 2% by drowning, 2% by falling (jumping to one’s death), and less than 1% by suffocation, train, or vehicle, while another 25% died by handgun, 10% by shotgun, 5% by rifle, and 19% by hanging. One person killed herself by carbon monoxide and overdose. Otherwise there appear to be few differences between high and low intent. Their psychological pain was unbearable for all of them.

There were more nonwhites (12%) and women (32%) among those escaping psychological pain than in other groups. The individuals were also quite distinct from those escaping physical pain. They were more engaged with suicide, having made previous attempts and having suicidal ideation, yet some of them were less sure they wanted to die. They shared the greatest similarity with those in the grief and failure groups. The escape-psychological, grief, and failure groups had the fewest gun deaths and had similar percentages who killed themselves by overdose and asphyxia. While it can be difficult to know for certain or to measure accurately how much someone wanted to die, lethality has become a measure for researchers (Haw, Hawton, Houston, & Townsend, 2003).

Intent can also be inferred by looking at words and actions in addition to lethality. Only 13% of note writers in this group said life was not worth living, as compared to those who were escaping multiple problems (26%) or physical pain (24%), suggesting that more people in this group could still imagine a life worth living. They also had the least amount of constricted thinking of any group, suggesting that they had not become convinced that death was inevitable. In Figs. 6.5A and B one can see that lethality is the only substantial difference between the high and low intent subgroups, which is why in Fig. 6.1, at the beginning of the chapter, both subgroups reside near the center of the diagram.

A number of possible interpretations of this information exist. As sufferers of psychological pain, they may have been more introspective than those in other groups. Indeed Schneidman (1999) describes psychological pain as “the introspective experience of negative emotions such as anger, despair, fear, grief, shame, guilt, hopelessness, loneliness, and loss” (p. 287). He called this “psychache.” The psychological pain associated with severe depression is often perceived by its sufferers as worse than any physical pain that the individual has experienced (Mee, Bunney, Reist, Potkin, & Bunney, 2006). Psychache makes up a large portion of the group composite images of those escaping psychological pain, with both high and low intent (Figs. 6.5A and B), and of those in the interpersonally abusive group (Fig. 6.2), but it makes very little appearance in those escaping physical pain (Fig. 6.4).

There were differences between women and men that essentially correspond to the high and low intent subgroups. Women did not use guns. While we might conclude that this is simply a gender preference, it may be more than that. As we saw in the introduction, the rate for women taken to the hospital for a suicide attempt was nearly twice that of men, but the death rate for suicide among men was four times higher than for women (Daniulaityte, Carlson, & Siegal, 2007). Women are twice as likely as men to suffer from depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001), but it is possible more of them get treatment for it than men (Weissman, 2014). Women who complete a suicide after previous attempts do not usually escalate the violence or lethality of the suicide method, but men do (Brådvik, 2007). It may be that women escaping from psychological pain are simply more ambivalent about death than men in the same category when they decide to commit suicide.

Reasons for Living

Those who killed themselves over grief and failure shared many characteristics with the psychological escape group. Predominantly white, there were more women in these groups than in other groups. They used few guns, and most died by asphyxia and overdose. Almost three-quarters of the time they killed themselves at home. Nearly a quarter had physical illnesses, and the rate of depression of those in the failure group were similar to those in escape-psychological.

The similarities of their characteristics may have something to do with the fact that the number of women in these groups was proportionally high in each. Likewise the people in these groups tended to have one problem. For those in psychological pain, that was their major impediment to living. Many people experiencing grief had no compound major problems. The loss of their loved one made life unbearable (Fig. 6.6).

Those in the failure group did often have multiple problems, at least to outward observers. However, it may be that “failure” itself was the singular problem in the eyes of the victims. Maybe life did not seem completely worthless to the people in these groups because they really only had one problem that, if gone, would have made life worth living. Their choices of means other than guns to die suggests ambivalence. It is possible that had some life-affirming events or social supports been present to counter the grief or failure, some of these suicides might have been prevented.

Having a reason to live that supercedes the reason to die is frequently identified as a protective factor (see discussion in Chapter 9: Protective Factors and Resilience). Many of the victims in our sample who suffered from psychological illness, grief, or failure identified the absence of a reason for living as the problem. “We are ruined, our marrige and our financial situation… I have given up on love, trust, faith & hope’s & dreams,” mourned a 42-year-old woman who had diabetes and psychological problems. Nick was searching for a reason to keep going, but none appeared: “I have been a failure in my own eyes my entire life. There is nothing that I excel at. There is nothing where I am the best.” A 30-year-old woman who was tired of “being such a failure” made it clear that it was her failure as a mother that was propelling her toward death. She had just lost custody of her children. “I miss them so dearly—no one could imagine.”

Outside observers cannot always tell what might be a person’s reasons for living. The individuals in our study left behind children, parents, spouses, siblings, friends, and pets whom they loved. Loving others may be one person’s reason to live and not another’s. Three-quarters of note writers mentioned love for others. The issue is not whether others could find a reason for living in the suicide victim’s circumstances, but whether the suicidal person could. In the psychological escape, grief, and failure categories, they were able to identify reasons for living (marriage, being good at something, parenting), but having those things eluded them. People in other groups were unable to identify reasons for living. Thought processes were critical. Constricted thinking, such as tunnel vision or dichotomous thinking, may affect one’s ability to be able to identify a reason for living (Jobes & Mann, 1999). In those escaping multiple problems, financial problems and legal problems, we can see the effects of constricted thinking on their loss of a reason to live (Fig. 6.7).

Effect of Overwhelming Problems

Those who were escaping multiple problems might be expected to straddle the categories in escape we have just discussed, but in fact, they were quite distinct. This group, like the interpersonally abusive relationship group (Fig. 6.2), was highly volatile and impulsive in a way the other escape-psychological (Figs. 6.5A and B) and physical (Fig. 6.4) subgroups were not. If we look at their rates of interpersonal problems, physical and unspecified pain, physical illness and legal and financial problems, as discussed in Chapter 4, Escape as a Motivation for Suicide, we see lives that seemed to be a “mess.” They also had the highest rate of negative emotions in their suicide notes, and exhibited constricted thinking. Like those in the interpersonally abusive relationship group, they could not see a way out of their misery. Their lives were falling apart and, in their minds, they were out of options. They felt they had no choice but to die.

Those escaping multiple problems also face challenges in getting help because of a combination of circumstances that surround not just the number of issues but their complexity. Constricted or rigid thinking may precede the onset of planning the suicide and may be the usual way a person with multiple problems thinks. In other words, the constricted thinking is typical for them. That pattern of thinking may be shared with the person’s social milieu, where many have poor problem-solving skills. This might be especially true for adolescents who rely on their peer group more than on professional help. Moreover, expertise in all the problem areas is not likely to be found in any single individual who is present to help the person. The person who can provide psychological counseling is unlikely to be equipped to provide financial counseling. Referral to someone else may seem to the suicidal person like adding to the set of problems. A mindset of help-negation, i.e., the refutation of all help-related suggestions for myriad reasons (“I can’t, because…”), can set in among multiple parties, the victim and family or friends, as the problems mount. Help-negation can increase the risk of suicidality (Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, 2001; Joiner, Walker, Rudd, & Jobes, 1999). This is a group that gives mixed messages about wanting help and resists accepting it, not purely out of obstinacy, although it can be perceived that way. Often there is a confluence of reasons for the help-negation that includes constricted thinking, mental illness, substance abuse, and myriad personal issues. This category cuts across race, gender, and class lines.

It may seem difficult to imagine a more complex category than those trying to escape from multiple problems, but those trying to escape legal problems is arguably more so. Like the interpersonally abusive group (Fig. 6.2), those escaping legal problems (Fig. 6.8), while predominantly white and male, had a significant number of minority individuals. Also, like both of the interpersonal subgroups, the average age at death, 37, was younger than in other groups. The only group with a younger average age was the financial problem group at 35. Some individuals in this group had hypermasculine traits, including risky and violent behavior.

The largest number of deaths occurred by asphyxia, which reflects the high number in jail. Those who had access to guns used them. In some ways, those escaping legal problems had multiple problems, but they only died because of their legal problems. Like those escaping multiple problems, those escaping legal problems had complicated lives. They exhibited some of the same high risk and violent behavior seen in the abusive relationship group, but a few were caught up in circumstances that simply became overwhelming and no reason for living more significant than their problems was on the horizon.

Only three of the people escaping legal problems left notes, so we have no way to determine the emotional states or other subjective factors for people in this category. More telling of their mindsets, perhaps, is the nonverbal communication among the 50 people in this category. In one case, police spotted a van driving erratically late at night and attempted to pull the driver over. Instead of complying the driver kept going for over an hour and 40 minutes, through several jurisdictions, over “stop-sticks” designed to puncture the tires of the vehicle. Eventually, the driver was forced to stop when his tires went flat. As the police officers approached the van, the driver put a handgun to his head and pulled the trigger. Individuals in this category resisted arrest, and after arrest hanged themselves, or as police approached spontaneously shot themselves. Citations for DUI often revealed problems with alcoholism. One 22-year-old woman who worked at an Air Force base killed herself after she was caught buying alcohol for a minor and getting a DUI. A large bottle of whisky was found in her dormitory room. While only a small number had addictive substances in their bodies at the time of their deaths, over a third had substance abuse problems. Suicide appears to have been an impulsive reaction to circumstances rather than a considered desire to die, but the individuals in this group, although impulsive, used highly lethal methods and clearly intended to die.

Despite the fact that incarceration rates have risen for all populations in the United States and in some countries in Europe since the 1980s, suicide rates in jails have decreased in many countries, including the United States (Fond et al., 2016), as we will discuss further in Chapter 8, The Intersection of Suicide and Legal Issues. Hayes (2013) found that suicides were evenly distributed across time, from the first few days of incarceration to over several months of imprisonment. Arrest and incarceration generate a host of problems, from the tangible, such as legal bills, to the ethereal, such as feelings of shame and guilt. But those who find themselves in legal trouble have something that those in other kinds of trouble often do not have, a definite day of reckoning from which there is no retreat (Fig. 6.9).

Financial problems sometimes also have days of reckoning, such as a foreclosure or a bankruptcy, though in some cases the problems seemed continuous and unending. Some of the decedents had gambling problems, a high-risk behavior, and had accumulated large gambling debts. Those seeking to escape their painful circumstances have the similarity of seeking escape, but they are not all similar with respect to how and why they commit suicide. Their motivation, escape, is also affected by their risk factors, which include their mental health and their belief systems or mindsets, such as constricted thinking. Those who sought to escape legal and financial difficulties did have one distinction from the interpersonal group or those in the other escape categories. They, more than others, faced systemic problems rather than personal problems. The trends of mass incarceration or the recessions that occurred in 1999–2000 and again in 2008–09 were forces beyond the control of these individuals. While their behaviors may have landed them in trouble, their ability to resolve their problems was made worse by circumstances over which they had no influence and perhaps which they did not even understand.

Conclusions

There are very different characteristics among and between groups of people who kill themselves. Prevention and intervention must be tailored to fit the groups. There are essentially two subgroups in the interpersonal relationships group, the unrequited love suicides and the abusive relationship suicides. For men in both subgroups, losing control in the relationship was the impetus for the suicide. Yet for the unrequited love group, the response was to turn inward; their suicides were predicated on loss. They may have internalized ideas of hegemonic masculinity in which they believed they ought to have been in control of their relationships, but most often they were not violent towards others. For these men, interventions that involve counseling make sense. As we noted in Chapter 3, Suicide Motivated by Interpersonal Relationships, hotlines may be of value since reaching out to someone may help break the isolation that they feel as a result of their loss.

For those in the abusive subgroup, the suicide is not a turn inward, but a turn outward. Even when the situation is not murder-suicide, the events are frequently aggressive, public and terrifying. Hotlines and counseling are not interventions that these men would accept, so other interventions must be devised. In Chapter 8, The Intersection of Suicide and Legal Issues and Chapter 10, Conclusions and Implications we propose some possible solutions.

Those who kill themselves for escape represent the most complex group to help, and indeed prevention and intervention have no one-size-fits-all model. When Baumeister et al. (1993) advanced his escape theory, he proposed that those who killed themselves to escape would exhibit a heightened sense of perfectionism, self-loathing when failure is present, negative emotional affect, high self-awareness, cognitive destruction, and disinhibition. Yet those qualities do not hold true for our escape umbrella, nor for the individual subgroups. There are demographic differences among those who die to escape problems.

Those who want to escape physical pain may be, in some cases, beyond help. This group more carefully planned their suicides and took steps to ensure there would be no intervention. They were not ambivalent in their wish to die. At the same time, their suicides were in response to situations that were not all inherently fatal or miserable.

For those attempting to escape psychological pain, prevention and intervention are very complex. There seemed to be ambivalence about dying among some of the people in this group. If a large number of individuals in any group wanted to be prevented from killing themselves, it appears to have been these. Yet, there was often no precipitant, so that a time to intervene was not necessarily obvious to family, friends, or even professionals such as social workers, counselors, or doctors. Since members of this group had been diagnosed with psychological problems, they had in fact sought help, but what existed was not continuing to work. Those suffering from grief or failure were similar to those escaping psychological problems. In none of these groups were the individuals trying to hurt others. Their actions were all directed inward, and the very quietness of these victims may have staved off intervention.

Those escaping multiple problems are also among those hardest to help, but not because they refuse to reach out. All the evidence points to this group reaching out or behaviorally acting out to get help. Yet because the set of problems is so complex, those who could help them often don’t know what to do first. For example, people suffering from depression and alcoholism have what is a called a “dual diagnosis.” Psychologists and social workers will often tell the alcoholic to get treatment for the alcoholism first, because it is impossible to treat the depression while the individual is still drinking. Yet the difficulties of getting treatment for the alcoholic abound. Many “treatments” are simply 12-step programs, which are not evidence based and sometimes have no professionals involved. For individuals who are clinically depressed, an Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) group may not provide sufficient care, although one study has indicated that membership in A.A. does decrease suicidality (Hashimoto & Ashizawa, 2012). In Europe treatment for alcoholism almost always involves medications to stop cravings, but in the United States, it rarely does (Jonas et al., 2014).

For people with multiple problems, all of which bear down on them at some point and snowball, the idea of tackling one at a time may appear overwhelming, both to them and to those who could help them. For all parties involved, the victim and those close to the victim, it may appear that death is the only way to stop the downward spiral. Thus, others share the constricted thinking or poor problem-solving affects of the suicidal individual, and may also perpetuate help-negation. Studies have documented that help-negation occurs for both professional and nonprofessional sources of help (Yakunina, Rogers, Waehler, & Werth, 2010). This cycle must be broken among all parties in order for the person to survive.

Those escaping legal and financial problems also resemble the escape multiple, but have some slight differences. The individuals in these categories also show some hypermasculine or hegemonic masculine qualities, like those in the interpersonally abusive relationship category. Yet the fact they were caught up in external economic and political forces may have exacerbated their problems.

A central question in all of the suicidal acts was whether and to what degree the victim was suffering from mental illness. In the next chapter, we explore mental illness and its role in causation.