Chapter 2. People in digital libraries

Think about your local library: besides the books, magazines, newspapers, DVDs, and computers, the library's key ingredient is people. Many are patrons (readers), but there are also several librarians, without whom there would be no library for the patrons to patronize. There are other staff as well, working behind the scenes: librarians in the cataloging and acquisitions department, IT personnel in the technical services department, and education specialists in the outreach department.

Think about your local library: besides the books, magazines, newspapers, DVDs, and computers, the library's key ingredient is people. Many are patrons (readers), but there are also several librarians, without whom there would be no library for the patrons to patronize. There are other staff as well, working behind the scenes: librarians in the cataloging and acquisitions department, IT personnel in the technical services department, and education specialists in the outreach department.

The emphasis on people is a fundamental principle of contemporary librarianship, and stands in contrast to medieval librarianship, whose job it was to protect, revere, and even chain up the books. Ranganathan's classic work

The Five Laws of Library Science opens with this quotation from Manu, an ancient Hindu philosopher and lawmaker:

To carry knowledge to the doors of those that lack it … even to give away the whole earth cannot equal that form of service.

What an inspirational sentiment for budding digital librarians with a social conscience! Ranganathan himself was an influential librarian and educator who is considered the father of library science in India. Librarians worldwide apply his five laws as the foundations of their philosophy:

• Books are for use.

• Every reader his [or her] book.

• Every book its reader.

• Save the reader's time.

• The library is a growing organism.

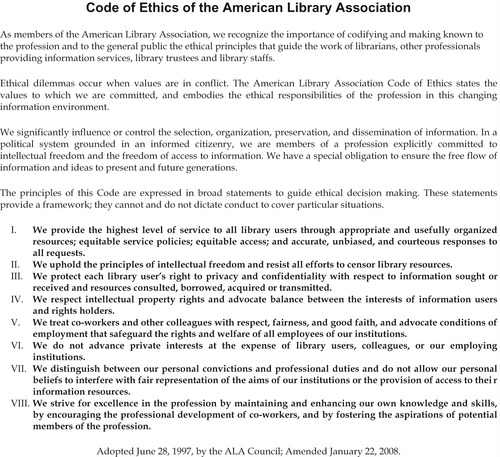

Today we live in a far more complex world—you can glimpse how much more complex by looking at the American Library Association's Bill of Rights in Figure 2.1. Nonetheless Ranganathan's principles remain at the center of librarians’ professional values. As you can see, they are as much about people as they are about books.

The first step in building a successful digital library, therefore, is to understand the people involved. Who are the likely readers? Why would they want to access the content? Do they need help or advice? Who will install, maintain, and update the digital library software? Who will look after the hardware that holds the actual documents? Who will cope with computer and network upgrades—and who will monitor their effects? How are the traditional roles of librarians affected by new technology? Can the users of digital libraries actively contribute to their development?

Other chapters discuss the technical details of file formats, metadata standards, digitization of material, and document representation. Here, as we begin with the most important element, the people, we need to define the various roles that people play in digital libraries. The transition from physical to digital removes many geographical constraints, which has an enormous effect on the people involved and introduces a host of new issues that traditional librarians could hardly imagine. Next we consider the central concept of “identity”: What does the new librarian know, or need to know, about who the users are and what they are doing?

The fact that users and librarians no longer interact face to face is an important change in library operation that is discussed in Section 2.3. In Section 2.4 we look at the issues that are raised when working with digital rather than physical material, both for readers and for librarians. Finally, in Section 2.5, we discuss what could be the most exciting new development in information access in the future: user contributions. Previously, users were severely discouraged from making contributions to library material: readers who contributed to (wrote in) library books were considered to be “defacing” the books, which had wholly negative connotations. But because the digital world offers selective access to altered material, defacing has been rebranded as “enhancing.” The digital world embraces the ability of users to contribute their expertise by making corrections and adding annotations, tags, ratings, and even entirely new material.

2.1. Roles

Libraries are social organizations that connect readers and authors through the content of their collections. Although reader and author are the most prominent roles, numerous people work behind the scenes to enable the simple act of reading a library book. Examining the roles that people play in a physical library will help us understand how to deploy and maintain a digital one.

A fundamental property of digital libraries is that they are, well, digital. Physical libraries are actual bricks-and-mortar buildings, occupying land, with windows, walls, and a roof. Indeed, as Chapter 1 describes, the new national libraries of the 20th century's closing decade are monumental in scale. In contrast, digital libraries occupy the far less tangible world of computers, of magnetic and optical storage mechanisms, of network connections and Web sites. These are striking differences, and they impose very different roles and skill requirements on the people who manage the collections and serve the users.

Several basic characteristics are common to most workplaces, including entrances and exits, lighting, temperature control, restrooms, security, parking space (or, more commonly, the lack thereof), and so on. Libraries have two particular extra characteristics: the patrons and the collections. Physical libraries are shared environments where many of the participants are present for relatively short periods of time. The documents and other objects have special requirements with respect to temperature, humidity, and sunlight exposure. Maintaining a suitable environment is a necessary condition for an effective physical library.

In digital libraries the computers still require space and associated services, but they need not be located at any particular physical place. Computers and collections can be distributed across different centers. Copies of the content can be replicated around the world; indeed, this is a good thing—to increase robustness, to reduce the effect of outages, and to preserve the material in the event of catastrophe. The people who manage the digital content may be physically separate from their colleagues, perhaps not even part of the same organization. Hosting of digital collections can be outsourced to the other side of the world in a manner that is obviously not an option for providing access to physical resources.

Wherever they are, maintainers of digital content have quite different concerns from custodians of physical material. They seek environmental conditions that help their computers and disk drives work smoothly, without interruption. Instead of opening hours, car parking, and patrons walking around the library, maintenance staff for a digital library worry about their network connections, firewall integrity, and the load on the Web server. Therefore, the skill sets for working in physical and digital libraries are very different: imagine the chaos that would result from swapping network support technicians for the help-desk staff in your own library!

In practice, most of today's libraries are hybrid organizations with both physical and digital elements in their collections. This means that staff must have the skills to cover both. Although the expectation that library material be Web accessible sprang up very rapidly with the advent of the World Wide Web, the transition to a digital environment has been reasonably gradual because computers have managed the metadata of physical collections ever since online public access catalogs (OPACs) began to replace library card catalogs in the 1980s (see Chapter 6).

Global users

Access to full digital content allows users to work far outside the library walls. Library holdings can now be accessed over the global computer network provided by the Internet. Today it is perfectly normal for a user to access library material even though neither user nor content is anywhere near a library building. The fact that there is no need to walk into the library removes all geographical restrictions on access. The result is that everyone in the entire connected world becomes a potential user of digital library resources.

This change has far-reaching consequences. In service-oriented organizations you need to know whom you are supposed to serve. Moving from the physical to the networked world makes it far more difficult to identify the user population (as well as making it difficult to identify individual users—see the next section).

Figure 2.1 shows the Bill of Rights of the American Library Association, whose aim is to promote library services and education internationally. We have already pointed out it differs from Ranganathan's simple, direct laws of library science. Notice in particular the first article: books and other library resources should be provided for the interest, information, and enlightenment of all people of the community the library serves. What is this community? It is well known and fully defined for almost every physical library, but for many digital libraries the community of users is effectively the whole connected world. The fifth article of the Bill of Rights also presents a challenge to digital libraries: a person should not be denied use of a library because of origin, age, background, or views.

The principles of the association's Bill of Rights are just as admirable today as they were when they were adopted 60 years ago. But there is a clear mismatch between the global distribution of potential users and the pragmatic local aspects of management, funding, accountability, and the legal environment. Patrons are more dispersed, but the funding base remains local. Worse still, budgets are shrinking, because librarians have to swim against a current of popular opinion that questions why, in today's culture of information overload, we need libraries at all.

Here is how a practicing librarian sees the dilemma.

It's a growing (ballooning, exploding even) challenge to balance my time between our primary patron base and the random people who find us on the Web. As a public institution, our upper administration has made it clear that, while we give priority to our primary patron base, we are to answer all questions, whenever possible.

Instead of trying to be all things to all patrons, one common approach is to restrict some services to users who can be identified through such means as usernames and passwords.

Roles of librarians

The digital environment has already significantly altered the roles of librarians and is likely to continue to change the nature of information work. Table 2.1 shows some of the differences between the roles of digital and physical librarians.

Just as librarians used to deal with physical objects, now they deal with digital content. Moreover, there has been an associated move from owning information to renting it. This trend strikes at the heart of the librarian's customary way of doing things. Today, publishers rarely sell digital copies of scholarly research—they license them instead. Digital rights management technology, introduced in Section 1.5, can enforce conditions that go far beyond those traditionally imposed by libraries. The effect on libraries—and society—is immense. A sea change is under way in the librarian's profession, from information-enabler to restriction-enforcer.

Acquisitions and collection development have always been major responsibilities of librarians. But now the job has changed from acquiring physical material to negotiating licenses for digital material. This is particularly striking in the realm of serials and electronic journals, but it will increasingly apply to acquisitions in general. Furthermore, libraries form consortia that negotiate group licenses with publishers at favorable rates. Because selecting electronic resources tends to be done by groups rather than individuals, this has the effect of diminishing the autonomy of individual libraries and subtly changing the role of individual librarians.

Another issue related to acquisition is digitization of physical content. As Chapter 4 explains, digitization is the process of taking traditional library materials, typically in the form of books and papers, and converting them to an electronic form that can be stored and manipulated by a computer. Many libraries own special collections and unique materials like rare books and manuscripts. There is a strong incentive to use digital library technology to make these materials available electronically, widening access to a far larger user group and increasing the library's profile and reputation.

Although physical libraries need IT support, it almost always involves installing and maintaining integrated library systems supplied by major vendors. In contrast, digital libraries frequently use open source software and often run several different software systems in parallel. This greatly extends the support requirements. Digital libraries need to establish and maintain a Web site—quite a different proposition from running a traditional library system. The software will have to be updated regularly, and occasionally the library's entire content will have to be migrated to new hardware and systems.

An overarching challenge for all librarians is to integrate access to traditional library material (owned), online journals (licensed), and information on the Web (publicly available) into a one-stop shop that recognizes the different legal status of the material. Many difficult issues arise, such as how to reconcile site licensing with walk-in library patrons. (A related question is what will happen to today's students when they graduate and find their university library's doors metaphorically closed by licensing restrictions?) Some libraries even aspire to service their patrons’ e-books and personal digital assistants, which raises legal questions about delivery models and technical ones about expansion-card compatibility. Countless new roles are being forced upon the librarian.

Change

This brings us to the question of change. We stand at the epicenter of a revolution in how our society creates, organizes, locates, presents, and preserves information. Librarians are undoubtedly among those most radically affected by the tremendous explosion in networked information sparked by the Internet. Advances in information technology generate an onslaught of opportunities and problems that pose a fierce and sustained challenge to librarians’ self-image. As just one example: consider the challenge to librarians inherent in Google's declaration that its mission is “to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful”—a mission that librarians thought society had entrusted to them alone, and which they had been doing well for centuries.

Of course, change has been ever-present throughout the history of library development, as the synopsis in Section 1.2 illustrates. Furthermore, change is especially true in the digital realm, since technological change continually produces new forms of content and new methods of access. For library staff to work successfully under these conditions, they must continually adapt their skills.

The ultra-fluid environment places stress on managers as well, since they must organize an increasingly diverse workforce. A noted author and columnist about libraries looks for these traits when recruiting new digital librarians:

• capacity to learn constantly and quickly

• flexibility

• innate skepticism

• propensity to take risks

• public-service perspective

• aptitude for teamwork

• facility for enabling and fostering change

• ability to work independently.

This checklist recognizes the need for digital librarians to adapt to technological change. New standards, protocols, delivery mechanisms, and opportunities are continually appearing and have the potential to reshape the digital workplace beyond recognition.

In fact, whole new lines of business can spring up from nowhere. New software systems can create an entirely new area of responsibility for librarians in the space of just a few years. The growth of institutional repositories in the university and research institute sector is a case in point. An institutional repository is a system that collects, preserves, and disseminates the intellectual output of an institution. It is open to worldwide access, often without any restrictions.

With the advent of institutional repositories, librarians became responsible for soliciting new content, negotiating over copyright, managing rapidly changing software systems, and migrating content between the new systems. The new job title

institutional repository manager hardly does justice to the complexities of this role. In an amusing article that critically analyses the current state of affairs, Dorothea Salo, Digital Repository Manager of the Wisconsin Digital Collections Center, likens herself to the innkeeper at the Roach Motel: data goes in, but it doesn't come out. She remarks that

repository management is a new subspecialty, so new that most academic librarians of my acquaintance have no idea even how to introduce repository managers to other librarians and (more importantly) to faculty.

The quotations in Table 2.2 give a flavor of the chaos and misunderstanding that surround institutional repositories, and the opposition and—occasionally—praise they evoke. However, this is tangential to our focus here, which is the diversity of skills that staff need. In the same article, a librarian brought in specifically to run the repository is described as a “maverick manager”:

| “Institutional repository? Forgive me, but—that sounds vaguely obscene.” ( Graduate student in psychology) |

| “What? No! I'd never want those [preprints] on the web! They're not authoritative! I'd never use them, either!” ( Senior professor of engineering) |

| “[Engineering faculty] don't even know the library exists. They never go there; they download all they need. The library doesn't even register with them.” ( Engineering IT manager) |

| “This is Dorothea Salo. She's our—she does all kinds of nifty digital stuff.” ( Librarian) |

| “We don't need to be running all that fancy digital stuff. We need to hire some real librarians.” ( Librarian) |

| “I can put all that in? That's great! Why haven't I heard of you before?” ( Faculty member, public policy) |

Her job description usually includes policy and procedure development, outreach, training, metadata, maintenance chores such as batch imports, and permissions management; it may include programming, systems administration, or Web design as well.

Such managers have no well-defined place in the library's organizational structure. They may report to units as varied as special collections, digital collections, or online systems.

The fact that many academic institutions have given their library staff this new role—that of publisher—attests to the uncertainty that surrounds the place of libraries in organizations today. Unfortunately, new responsibility is not necessarily accompanied by new funding—as the “roach motel” metaphor implies. All these factors play havoc with the positions and job requirements of individual librarians.

2.2. Identity

The Internet, in particular the World Wide Web, lends itself well to anonymous access. Rather, it lends itself to the

appearance of anonymous access. In practice, as many people have discovered to their cost, users are often more identifiable than they realize.

Anonymous use

Librarians have always been concerned about protecting both freedom of expression and the privacy of patrons. With regard to the former, Article IV of the Library Bill of Rights (Figure 2.1) requires librarians to cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with supporting (i.e., “resisting abridgement of”) free expression and free access to ideas. With regard to the latter, Article III of the American Library Association's Code of Ethics, reproduced in Figure 2.2, puts it very clearly: librarians must protect each user's right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought and resources used. Librarians around the world share the concerns of their American colleagues about ethical issues related to both censorship and privacy.

Most people believe that access to information benefits society as a whole. Public library services are provided without profit for society collectively—in other words, they are a “public good.” The economist Paul Samuelson was the first to develop an economic theory of public goods, which he defined as ones that

all [people] enjoy in common in the sense that each individual's consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual's consumption of that good.

A so-called “pure” public good has the further property that no individual can be excluded from consuming it, which is particularly pertinent to Web-based digital libraries. It is hard to quantify the value to society of free access to information—or indeed the value of knowledge or education in general.

Libraries typically allow anonymous public access to physical resources, and also to some digital resources. Of course, in order to borrow materials it is necessary to provide some form of identification as surety. However, librarians guard the confidentiality of users to the greatest extent possible, on the basis that if confidentiality is compromised, freedom of inquiry is also compromised. If records of user activities are stored, it is possible that someone may later be able to retrace a user's actions, including the search terms they used and the materials they accessed.

American librarians are particularly concerned about demands being made by the government under the controversial USA Patriot Act, signed into law in October 2001, which increases the ability of law-enforcement agencies to search telephone, e-mail, medical, financial, and other records, including library records. Although some librarians suggest defiance, most agree that federal requests for data should be dutifully complied with, but only when a proper court order is served, and not just because a government agent asks for information. Of course, if fewer records are kept, less information can be provided. The Patriot Act does not require additional record keeping; only that anything that exists must be made available to federal authorities. Libraries usually keep minimal records and have a policy of erasing information immediately after use.

Anonymous access is one way of ensuring that users’ privacy is maintained. Patrons in physical libraries usually leave no trace of their actions (although some libraries have installed surveillance cameras, which itself has raised concerns about invasion of privacy). The same cannot be said for digital access, because electronic fingerprints are left in the user's workstation and the library's information system. However, remote access gives an impression of anonymity, and most users are unaware of the electronic trails they leave. Those who are aware do not worry unduly, because they expect that libraries will not pass on or otherwise misuse personal data.

Their confidence may be misplaced. Privacy issues in traditional physical libraries are clearly defined and well understood, if not always agreed upon. In contrast, the issue of privacy in a digital environment is murky. It is clear that users’ privacy is far less shielded from the librarian, or from those who have access to the library files, and users are therefore exposed to greater risk of disclosure from at least two sources: accidental mistakes and government agencies that can compel disclosure. Moreover, with digital technology the usage data that libraries acquire has potential interest not only for law-enforcement and security agencies, but also for commercial organizations and for the library itself, in order to assist with marketing.

Authenticated use

A practical issue in allowing public access to a digital library is whether one user's activity interferes with others. We have all experienced Web sites that are slow to respond to requests. Response time is influenced by a variety of factors (e.g., network speed), but the presence of other users obviously makes systems less responsive. This effect can be mitigated in three ways:

• technical measures, ensuring that the software is configured appropriately

• economic measures, such as purchasing more computer power and faster connections

• social means, such as restricting access to identified users.

The first two measures may have little impact if the service is popular and the user base is uncontrolled.

When establishing a digital library, you must think carefully about whether you are aiming for public access—which inevitably means global access—or a specific target group of users. One compromise that has been adopted by many digital libraries is to permit public access to metadata but to restrict access to the full digital content to registered users.

Three simple methods of restricting services are:

• logical—restricting access to an organization's network domain

• physical—restricting access to particular locations in the real world

• financial—restricting access to users who are prepared to pay (a “paywall”).

Users may be asked to identify and authenticate themselves via usernames, passwords, or PINs, or by connecting to the system from pre-distributed software. In addition, users may have to supply bank account or credit card information.

While paid electronic services may seem to inevitably leave audit trails that can be used to trace the user, this is not necessarily so. Strange as it may seem, new information-security methods can arrange anonymous electronic cash transactions and guarantee the user's privacy using mathematical techniques. These methods provide assurances that have a sound theoretical foundation (in contrast to security that depends on human devices like keeping passwords secret). Even a coordinated attack by a corrupt government with infinite resources at its disposal that has infiltrated every computer on the network, tortured every programmer, and looked inside every single transistor cannot force machines to reveal what is locked up mathematically. In the weird world of modern encryption, cracking security codes is the equivalent of solving puzzles that have stumped the world's best minds for centuries. Whether electronic money transactions leave audit trails is not dictated by technology but remains a choice for society. Anonymity is an option that society has so far declined.

Digital libraries often provide management and administrative functions through Web sites. In these cases, authenticated or restricted use is essential; otherwise, users have the same power as managers and administrators. Section 2.5 explores how this idea can be used to dramatic effect to allow users to contribute to the library. Section 7.7 discusses authentication in more detail.

Recording usage data

The traditional way of recording usage in libraries is to record nothing at all. Nothing, that is, unless books are borrowed, in which case an anonymous date stamp was placed inside the front cover, as Figure 2.3 illustrates, and the librarian made a physical note. However, library lending is now administered by computer-based systems, moving usage records to the digital domain. In fact, digital records apply to many areas of society: daily activities such as credit card purchases, telephone calls, and airline ticket purchases are routinely stored for later analysis through techniques like data mining and cross-database linking. The patterns derived often reveal interesting information. In a digital library they might tell you what users are

actually doing, as opposed to what you

think they are doing. However, digital records can lead to unforeseen consequences.

Here's an example. In August 2006, the Internet services company America Online (AOL) released to the research community the records of 20 million user searches. Their intention was laudable: they wanted to advance research on searching methods, which before then had been seriously handicapped by a lack of information about actual user behavior. Of course, all personal information had been removed from the records—or so AOL thought. But pretty soon journalists from the

New York Times were able to identify that user number 4417749 was in fact Thelma Arnold of Lilburn, Georgia, USA (they sought her permission before exposing her). They did so by analyzing the search terms she used, which apparently ranged from

numb fingers to

60 single men to

dog that urinates on everything. Search by search, they reported, her identity became easier to discern. There were queries for

landscapers in Lilburn, Ga, several people with the last name

Arnold, and

homes sold in shadow lake subdivision gwinnett county georgia, which reporters correlated with public databases, such as phonebooks.

This episode is a graphic illustration of the power of recorded usage data to reveal the identity of real people—even when the data has been anonymized. AOL quickly acknowledged its mistake and recalled the data. The repercussions were severe: their chief technical officer resigned, and two employees were reportedly fired. But you cannot erase information from the Web, and anyone can still download the AOL files from mirror sites. If you wish, you can easily find out more about Thelma Arnold's interests.

Web servers and digital library software all routinely include the capability to record the actions of users. A typical Web server log entry looks like this:

130.123.128.86 – – [17/Oct/2008:15:56:08 +1300]

"GET /gsdl/cgi-bin/library.cgi?a=q … &q=snail+farming … HTTP/1.1"

200 7544

Log files can contain millions of such records—one for each time the Web server is accessed.

Here's what this rather mysterious entry means. The four-part number at the beginning is the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the request, which could be the user's computer or, more likely, a “proxy” server somewhere between the user and the Web server. The “– –” on the first line sometimes gives the user id of the person requesting the document. This is determined by authentication using the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP); for almost all Web accesses, it is not defined—as in this case. Following a timestamp that specifies exactly when the request was made, the next part is the request type—in this case GET, which retrieves information from the Web server. (Another possibility is POST, which allows users to submit large quantities of data, such as uploading files.)

The next entry is the resource requested—in this case, to execute a program called /gsdl/cgi-bin/library.cgi with certain specified arguments given after the question mark (discussed below), and to return the output. (More commonly, requests give a simple URL without any arguments, in which case the corresponding static Web page is returned.) Following that is the protocol used, in this case HTTP version 1.1. Then comes a status code: the 200 indicates a successful request (whereas 404 is sent when the server can't find the requested information). Finally, the size of the response is indicated—a 7544-byte Web page was returned to the client.

This particular example happens to request information from a digital library—the Greenstone digital library software (the /gsdl/cgi-bin/library.cgi part reveals this). In fact, it results in an entry in a second log file, the digital library's own log:

/gsdl/cgi-bin/library.cgi its-proxy1.massey.ac.nz

[Fri Oct 17 15:57:28 NZDT 2008]

(a=q, c=demo, l=en, m=50, o=20, q=snail farming, w=utf-8,

z=130.123.128.86-950647871)

"Mozilla/5.0 [en-US] Firefox/3.0.3"

Despite superficial differences, this log entry provides much the same information as the Web log entry discussed above. On 17 Oct 2008 a user at its-proxy1.massey.ac.nz (this computer has IP address [130.123.128.86]) sent a request to Greenstone. The nature of the request is encoded in the arguments (some were omitted from the earlier example purely to make it more digestible). Interpreting the arguments reveals that the user issued the query

snail farming (q=snail farming). Other arguments request the result page in the English language (l=en) to the given query (action a=q), when searching the

demo collection (collection c=demo). The user's browser is Firefox version 3.03. Other arguments give the number of search results to be returned (m=50), the number displayed per page (o=20), and the encoding scheme used (w=utf-8). The last argument, z, is a “cookie” generated by the Web server: it is comprised of the user's computer's IP number followed by the time that it first accessed the digital library.

Can this information be used to identify the user? We know that the request came from its-proxy1.massey.ac.nz, which is a computer at Massey University in New Zealand. Its name indicates that it is a proxy server through which user requests are relayed, rather than a workstation on a particular user's desktop. The proxy server keeps its own log, which we may be able to access—if we have a search warrant. Such information was, of course, removed from the AOL data. The most interesting part is the “cookie.” Web cookies are short messages that are sent by a server to a Web browser and then sent back unchanged by the browser each time it accesses that server. This identifies the user—not by name, or as a particular person, but in a way that allows the system to tell whenever they make a subsequent request. (AOL anonymized the cookies in its data by replacing them with a unique user id—4417749 in the case of Thelma Arnold. However, as she discovered, users often can be identified by their queries.) In this case we might search out snail farmers in Palmerston North, New Zealand (where Massey University is). How many can there be?

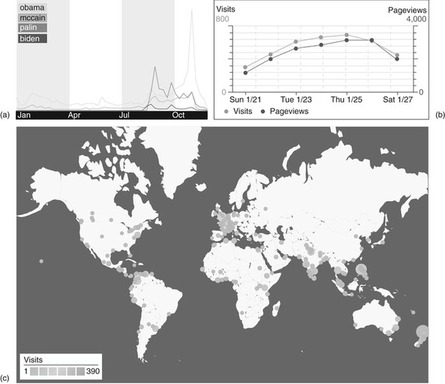

Specialist software is used to turn logs into concise summaries of Web server or digital library usage. For example, Figure 2.4a shows the number of searches for 2008 U.S. presidential candidates on Google throughout the election year. The major spike for

Palin occurred when she was chosen as McCain's vice-presidential running mate; that for

Obama was when he was elected President. Figure 2.4b graphs the usage of a particular digital library site during a single week in 2007. It plots both

visits (a total of 3,800), defined as a sequence of requests from a uniquely identified client that expired after 30 minutes of inactivity, and

page views (a total of 16,800), which are requests made to the Web server for a page. Figure 2.4c shows the geographical distribution of visitors.

|

| Figure 2.4: User log displays: (a) Google searches for U.S. presidential candidates during 2008 (from http://www.google.com/intl/en/press/zeitgeist2008/politics.html; slightly edited); (b) visits to a digital library; (c) geographical distribution of visitors |

Such data is useful for understanding what users are doing. It also reveals what technology they use to access your resources. If you wish to enhance your document presentation using particular features of Web browsers, it is good to know which browsers are actually being used.

2.3. Help and User Support Services

As with most things in life, accessing resources in libraries does not always go smoothly. Sometimes books are not in their expected place. Sometimes the computer system doesn't work properly. And sometimes the readers don't understand the organizational structures that the librarians have constructed. For these and other reasons, libraries establish services specifically to help connect users with resources that match their information needs. These services come in a variety of forms:

• information or help desk

• telephone help lines

• bibliographic instruction

• manuals and help guides.

Users must be physically present in the library in order to benefit from some of these services—like the help desk shown in Figure 2.5. However, over time, technological changes have allowed librarians to provide enhanced service in many different ways. The invention of the electric light extended library hours into the night. The telephone allowed reference librarians to serve patrons remotely. Today, libraries send SMS text messages to mobile phones to alert users that their book loans are about to expire.

|

| Figure 2.5: Library help desk: http://www.library.dcu.ie/images/shelpdesk.jpg |

With its users distributed around the world, hailing from many cultures, and living in many time zones, how can a digital library provide support services? In a physical library with a real help desk, the number of people who can make enquiries is limited by geography and opening hours—and sometimes by the length of the line at the help desk. In contrast, as libraries go digital, they have “absent users” who work remotely, accessing services via the Web. Therefore, a library on the Web has help services available to anyone who can find them. As the librarian quoted in Section 2.1 observed, this may force library staff to prioritize services or to restrict them to certain users.

Common forms of technology used in virtual reference services include:

• telephone

• fax

• e-mail

• Web forms

• text messaging (i.e., SMS)

• online chat (i.e., instant messaging)

• live voice chat

• live video chat (coming soon).

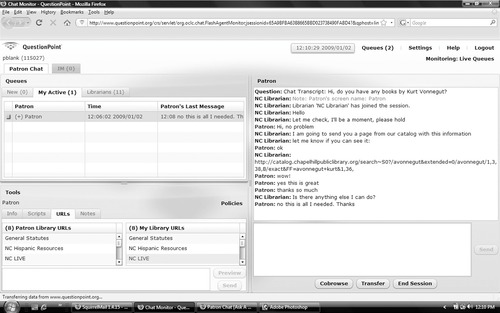

For example, Figure 2.6 shows a screenshot of an online reference interview in which a patron seeks books by Kurt Vonnegut and a librarian sends her a page from the online catalog. The figure is taken from a round-the-clock reference service that offers real-time one-on-one reference assistance from professional librarians, using Web-based chat, co-browsing, and cooperative reference tools. Offering remote help is a considerable technical and organizational challenge. Although help can be regarded as separate from the actual

content of a digital library, it is an important element in providing

access to the content. If its content is not easily accessible, can your digital library truly be regarded as successful?

|

| Figure 2.6: Virtual reference desk at NCknows (www.ncknows.org) |

About a decade ago, forward-thinking librarians began to realize that the survival of reference services in the era of Web search hinged on remote access. Indeed, some search engine companies experimented with such services on a paid basis. For example, from 2001 to 2006 Google offered a “knowledge market” that connected users with part-time researchers who answered their questions for a small fee. The practice came under heavy fire from some quarters because it sold a service that traditionally had been provided by public libraries.

Web-based online reference services are offered by libraries all over the world: for example,

Ask a Librarian,

Ask a Question,

Ask Now, and

Answers Now. Libraries band together to provide regional coverage, both for local readers and for outsiders who seek information about the region. Users are encouraged to contact services close to where they live, and they must begin their inquiry by providing residence details before their question is addressed. However, most virtual reference services have no way of determining whether the user is telling the truth. Some U.S. libraries ask users to enter their ZIP Code to check that they reside in the appropriate area, but there is nothing to stop people from using ZIP Codes they have found in a directory.

Thinking about help and reference services for users highlights the importance of having a clear picture of the role of the library. For example, the Library of Congress's online service states that its “primary mission is to serve Members of the Congress and thereafter, the needs of the government, other libraries, and members of the public.” In many digital libraries the situation is not so clear. But you must certainly consider whether you are providing services for members of your organization or for the whole world. And you must determine what form of authorization or identity system you intend to use to distinguish proper users from the random people who find you on the Web. Of course, many organizations already have a mechanism for detecting internal users, in which case it needs to be integrated, if possible, with the software of the digital library system.

2.4. Working with Digital Collections

What is the point of your digital collection? Or, more precisely, why would anyone want to access the content? The beauty of libraries is that, no matter how you answer such questions, it is impossible to predict who will find your collection useful, or when, or how. The variety of possible interactions leads to the question, What exactly will users want to

do with your digital collection?

The take-home message is to understand what services you intend your digital library to provide to its users. To do this, you need to understand how users will interact with the content, and balance your desire to support them against the technical and organizational demands of providing ever-richer services.

Using information from digital libraries

A simple answer is that users want to read the documents—or, in the case of multimedia items, view, listen to, and interact with them. A more nuanced answer might take into account what users are trying to achieve. Do they want to save the digital object to their own personal workspace? Do they want to share it with others? Do they want to cut out a portion and use it in a new document of their own? Do they want to provide a link from their Web site to an item in the digital library?

Although it is possible to extract portions of paper documents, doing so often risks damaging the original—and incurring the wrath of librarians. You can quote text from books and papers, but quoting from multimedia objects like video or audio is much more difficult—especially if they are in analogue form. However, it is relatively easy to extract portions of digital items and re-use them. Furthermore, digital copying leaves the original content completely unaffected.

The copy and paste metaphor is familiar to anyone who has used a word processor or image editor. The same principle applies to audio and video, although the programs usually offer more controls. The ease of copying encourages users to extract things from a digital library and to repurpose them in whatever ways they see fit. Once digital content is placed online, it can immediately be copied, legally or otherwise, and used again. And copied again, and so on. Furthermore, it can never be taken back—as AOL discovered when they released their search logs.

Extracting content from a digital library can be made more difficult by using display technologies that attempt to restrict undesirable, unofficial, or illegal usage. (However, the downside is that material becomes less accessible to the intended users.) Some display formats have features that restrict their use. For example, some documents can be secured so that they can be viewed on screen but not printed (e.g., the PDF format described in Section 4.5). As a simple first step, a library should at least make the copyright status of its documents clear to end-users—although, as noted in Section 1.5, the legal considerations may differ from country to country.

Users of a digital library should be clear about any restrictions on how they can use the content. Examples include:

• Can an end-user display video content in a public venue?

• Can audio content be sampled or remixed into new musical works?

• Can search engines index the textual content?

Some digital libraries offer users an opportunity to combine (or “remix”) photographs, graphics, film clips, music, and text to create new multimedia displays. For example, a library might make available multimedia objects pertaining to some event of local or national significance and invite patrons to use a Web-based video tool to create their own expression of what the event means to them. The newly created artifact could then be entered into the digital library.

Referring to objects in a digital library

Another aspect to the “use” of a digital object is the extent to which it can be included in the Web's link structure. Having found something of interest, a library user might bookmark it or link to its URL. But will the URL change if other items are added to the library—that is, will it be

persistent? Valid hyperlinks are the glue that holds the Web together, and references are much less effective if they break easily. The same question can also be asked about searches (Will the list of results for a particular search term in a digital library be persistent?) and about parts of the browsing structure provided by the library (How persistent is the list of documents whose titles begin with the letter

A?).

When evaluating digital library software, you should consider what happens to the URLs of objects in the library when:

• new items are added to a collection

• existing items are deleted

• the digital library's Web server is reorganized

• the collection is moved to another computer

• the collection migrates to a different software system.

As their name indicates, URLs (Uniform Resource Locators) are

locators that specify how to find the file containing the information. Fortunately, it is possible to put a “redirect” on the Web server that automatically redirects users to a different location, that is, a different URL, when the original URL changes. Because they are locators, URLs do not usually survive radical events such as server reorganizations.

Many schemes have been devised to make identifiers of digital objects persist over time despite organizational changes in the underlying software systems, Web servers, and their location on the Web. We discuss these schemes in Chapter 7.

Berry-picking

When people interact with information-retrieval systems, they typically encounter not just one, but several, items of interest that they wish to pursue further. Many systems provide mechanisms for users to maintain a cache of interesting items:

• bookmarks or favorites in Web browsers

• shopping carts in e-commerce stores

• marked or tagged lists of records in library catalogs.

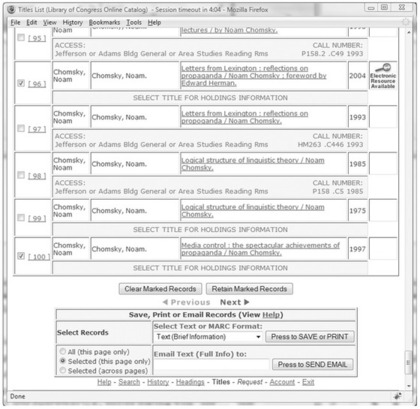

Here we call such lists of interesting items

berrybaskets—a term that evokes the idea of picking the ripest and juiciest fruit from a bush—and are essential for the effective use of large collections. Figure 2.7 shows an example of this, taken from the Library of Congress's vast online catalog. In the figure, a user is browsing the listed works of Noam Chomsky (there are over 190). Check boxes are provided down the left-hand side to select items of interest and our user, interested in the topic of propaganda, has selected relevant works. Once satisfied with the selection (perhaps visiting subsequent pages) she may save it, e-mail it to herself or a colleague, or print it as a paper record of the library visit. Commercial systems typically provide the option to purchase the items on the list.

Berrybaskets raise the same questions about identity that were addressed in Section 2.2. Are users—and therefore their baskets—anonymous, or do they need to provide authentication? As knowledge work becomes increasingly collaborative, people find it useful to share their lists, either publicly or with specific groups of friends or colleagues.

2.5. User Contributions

Ask not what your library can do for you, ask what you can do for your library.

Paraphrased from President Kennedy's inaugural address, 1961

Although the ALA Bill of Rights in Figure 2.1 asserts that libraries are forums for information and ideas, we have seen that libraries are really providers of services and users are consumers of resources. Most libraries offer little scope for users to

contribute content or metadata. However, many Web sites have shown that offering users a more active role in collection development can yield startling benefits.

Even before the advent of the Web, some were suggesting that user-supplied data might begin to address the information overload we all experience. Of course, librarians traditionally discourage patrons from adding value to paper materials (or defacing them, as librarians tend to see it). Neither did librarians permit users to add their own cards to the card catalog. However, with digital content, readers can choose whether to access the original version or a user-enhanced one, because user contributions are stored separately from the original content and can be combined or viewed separately as the occasion demands. An example application of this is illustrated in Section 12.2 (Design pattern 5) where a user can augment a sheet music digital library with “post-it” style annotations.

Most digital library systems are still conceived of as read-only repositories, where users are consumers rather than contributors. But the much-heralded Web 2.0 revolution's aim is to harness social effects and to create Web applications that improve as more people use them. In library terms, this requires a change of mindset from creating information for patrons’ use to creating an initial structure that patrons can supplement. Thus, libraries can evolve from exclusive suppliers of information that users consume into a partnership where both the library and its users supply material.

What kind of information could users supply? Here are some ideas.

Annotations

Many readers add notes in the margins of their books: to highlight important points, to make links with another concept (in another book), or to disagree with the printed text. The annotations may be personal, but they do not have to be: they could be shared with other readers. Some people might prefer annotated books over clean ones—particularly if they respect the annotator's opinion on the topic.

Keywords

A special form of annotation is the addition of keywords or tags. Keywords are terms that provide a useful summary of important topics associated with a document and can be used in a digital library to enhance searching and browsing. Keywords and tags build bridges between the documents and the user's vocabulary and also create new associations between documents—just as traditional author-assigned keywords do.

Ratings

Ratings are another special kind of annotation: they are a quantitative assessment on a particular scale, usually numeric. We are familiar with ratings for all kinds of everyday goods and services, from films to laptops to airline food. Ratings are easy to add to a document, and numeric ones lend themselves to computational processing, such as averaging and sorting. Amazon and other e-commerce sites use ratings to enhance their display of search results, and, together with usage data, to personalize results for individual users.

Corrections

Users can also supply error reports, signaling to the librarians that something is wrong with the collection. This can be as simple as a single click marking a piece of metadata as inaccurate—perhaps a typo in the author's name. For error correction, the user interface must allow users to flag errors easily, and the interface must be backed up by an infrastructure that summarizes the feedback and communicates it to librarians. Most digital libraries do not allow users to contribute in this manner, missing out on a potentially valuable source of quality improvement.

New documents

Finally, users can, in principle, add new documents, although collection development is usually regarded as a role that needs to be performed, or at least moderated, by a trained librarian. Many Web technologies have allowed unstructured and unmoderated groups of documents to proliferate on the Internet. However, there is a middle ground between a read-only library and a chaotic user-supplied document dump.

A common example of user-initiated document submission integrated with librarian oversight is the institutional repository discussed in Section 2.1 and demonstrated later in two worked examples (Sections 7.6 and 11.6). As with annotations and ratings, user-initiated document submission relies on digital library software to support both users and librarians in expanding the collection.

Partial and fluid documents

As mentioned in Section 1.2, in the first half of the 20th century, both H. G. Wells and Vannevar Bush prophesied the emergence of new and all-encompassing forms of encyclopedias and libraries. Both foresaw user contributions as the key to creating and maintaining such structures. As Vannevar Bush put it,

Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them.… There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record.

The most striking example of user contributions on the Web (or anywhere else) is the Wikipedia project. Launched in 2001 with the goal of building free encyclopedias in all languages, Wikipedia is today easily the largest and most widely used encyclopedia in existence. Wikipedia contains 10 million articles in 250 different languages. The English-language version contains 2.5 million articles totaling around 1 billion words (in 2008). Debates flare up about the quality of the articles and the reliability of the content, but Wikipedia has become a valued reference source for many Web users.

From its inception, the project offered a unique, entirely open, collaborative editing process, scaffolded by then-new wiki software for group Web-site building, and it is fascinating to see how things have flourished under this regime. Wikipedia has effectively enabled the entire world to become a panel of experts, authors, and reviewers—contributing under their own name, or, if they wish, anonymously.

Wikipedia's growth is astonishing: the acquisition of 1 billion words in seven years requires the addition of an average 400,000 words, or about five full-length novels, per day. One key reason for this growth is the absence of technical barriers: if you can view an article in a Web browser, then you can change it (all you need to do is to click the

edit button at the top of the screen). Another advantage is that users can make incremental changes. An edit can add (or delete) large amounts of text or a single character. Text that is deleted is not removed from the system: it can be easily reinstated.

Figure 2.8 shows the beginning of the Wikipedia article

Library. Its revision history shows that it was created on 9 November 2001 in the form of a short note (which, in fact, bears little relationship to the current version) and has been edited about 1500 times since then. Recent edits have added new links and new entries to lists, have indicated possible vandalism and its reversal, have corrected spelling mistakes, etc.

Wikipedia is very much a community effort. Each article has a discussion page that provides a forum for debate about how it might be criticized, improved, or extended in the future. The discussion page for

Library is almost as long as the article itself and contains the following observations, among many others:

Libraries can also be found in churches, prisons, hotels etc. Should there be any mention of this?

Daniel C. Boyer 20:38, 10 Nov 2003

Libraries can be found in many places, and articles should be written and linked. A wiki article on libraries can never be more of a summary, and will always be expandable.

DGG 04:18, 11 September 2006

Discussion pages are a unique feature of Wikipedia that has no analog in traditional encyclopedias.

Wikipedia will never be finished. While this means that anyone can corrupt articles by adding untrue or irrelevant statements, and nefarious users can even vandalize them, it also means that the information can be augmented whenever the world changes. Contrast this with books, which are potentially out of date before they are printed.

Therefore, the fluidity of Wikipedia articles contrasts with the fixity of traditional library materials. User involvement in knowledge creation and distribution is arguably a vitally important innovation. And user involvement requires the role of the digital librarian to expand again, to provide an infrastructure for knowledge production, rather than merely preserving existing content.

2.6. Notes and Sources

S. R. Ranganathan's classic book is called

The Five Laws of Library Science (1931). The Bill of Rights in Figure 2.1 and Code of Ethics in Figure 2.2 can both be found at the American Library Association's Web site (www.ala.org)

.Rubin (2001) discusses ethical aspects of reference services. Anderson (2006) gives a detailed discussion of the interaction between ethics and digital libraries.

The quotation in Section 2.1 from a practicing librarian comes from Szymanski and Fields (2005). For a frank account of running an institutional repository read Salo's (2008) priceless “Innkeeper at the Roach Motel.” The desired staff traits are from Roy Tennant (2004, pp. 150-151). Thornton (2000) explores the impact of electronic resources on collection development and foresees that consortia will become even more important because electronic resources, unlike traditional ones, can easily be shared.

The definition of public good at the beginning of Section 2.2 is from Paul A. Samuelson's classic 1954 paper, “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure

.”McCallum and Quinn (2004) and Holt et al. (1996) discuss attempts to quantify the benefits of libraries. The name of the USA Patriot Act is an acronym for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT). The Act took effect in 2001 and was so controversial that it had to be renewed by the U.S. Senate every year; most of its provisions were finally made permanent in 2006. The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has more information (www.epic.org).

Barbaro and Zeller (2006) were the

New York Times reporters who outed AOL user number 4417749. Many instances of unintentional information leakage to search engines relate to so-called “vanity searches,” which are searches for information about oneself (Soghoian, 2007). Sturges et al. (2003) discuss the parameters of privacy in the digital library environment.

The historical observation at the beginning of Section 2.3 that librarians have been able to expand services with each new technology is from Barnello (1996), who succinctly surveys more than a century of innovation in reference libraries. The “absent user” and virtual reference desks are discussed by Martell (2008), Kibbee (2006), Lankes et al. (2006), Courtney (2003) and Katz (2003). Beranek and Burke (2006) describe the development of a library telephone enquiry service. Sugimoto (2008) discusses the quality of reference transactions in academic music libraries. Figure 2.6 shows the QuestionPoint software system from OCLC. There's a useful list of “Ask a Librarian” services all over the world at http://askaquestion.ab.ca/referral.html. Pomerantz (2005) gives a comprehensive discussion of chat-based reference services.

Here is an example of both user contributions and remixing multimedia content. Around the 90th anniversary of the signing of the armistice that marked the end of World War I, the Auckland Museum in New Zealand invited patrons to help commemorate the anniversary. The museum made available relevant photographs, graphics, film clips, and music. Through a Web-based interface, patrons could craft their own expression of what the coming home of soldiers meant to them and upload it to the site to share with others. The result can be found at http://remix.digitalnz.org/.

Nelson and Allen (2002) describe an interesting study of object persistence and availability in actual digital libraries. Bates (1989) is the classic reference for the idea of berrybaskets.

Before the spread of the World Wide Web, Michael Koenig (1990) suggested that user-supplied metadata is a key mechanism for addressing information overload. Annotations are thoroughly explored by Marshall (1998) and Marshall and Brush (2004). The quotation about new forms of encyclopedia is from “As We May Think,” by Vannevar Bush (1945). To learn about Wikipedia, we recommend, well, the Wikipedia article on it: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia (available in 202 languages at the time of writing).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.