|

|

Work systems are becoming more complex, creating numerous challenges for those involved in making decisions that affect the design of work systems … Human factors and ergonomics (HFE) has responded to this challenge by embracing and adapting models and concepts that incorporate the organizational and sociotechnical context of work such as macroergonomics.

P. Carayon et al.

2015

In addition to the influence of the physical design of workspaces and the larger work environment, a person’s performance and well-being are influenced by many social and organizational factors. Job satisfaction is a function of the tasks that a person must perform, work schedules, and whether the person’s skills are adequate for the job. The degree of participation that the workers have in policy decisions, the avenues of communication available within an organization, and the social interactions experienced every day with coworkers and supervisors also play a major role in determining job satisfaction. Job satisfaction in turn affects a person’s physical and psychological health, as well as her or his level of productivity.

Productivity bears directly on an organization’s “bottom line” (profits), as well as on other measures of organizational success. The recognition of the fact that organizational performance is determined by the productivity of individual employees has drawn the human factors expert into areas traditionally left to management. The problems associated with job and organizational design, employee selection and evaluation, and management issues form the basis of the field of industrial/organizational psychology and human resource management. However, such organizational design and management problems are also of concern in human factors, because an employee must perform within the context of specific job expectations and the organizational structure.

The unique viewpoint that human factors specialists bring to job and organizational design issues is the systems perspective. An organization is a “sociotechnical system” that transforms inputs into outputs (e.g., Clegg, 2000; Emery & Trist, 1960). A sociotechnical system has technical components (the technical subsystem) and social components (the personnel subsystem) and operates within a larger environment (Kleiner, 2006, 2008). The technical and personnel subsystems must function effectively in an integrated manner, within the demands imposed by the external environment, if the sociotechnical system is to function effectively as a whole.

Macroergonomics is a term that describes the approach to the “human–organization–environment–machine interface,” beginning with the organization and then working down to issues of environment and workspace design for the individual worker in the context of the organization’s goals (Hendrick, 1991). Macroergonomics therefore focuses on organizational issues and their relation to human–machine interface issues (Kleiner, 2004). The goal of the human factors expert is to optimize human and system performance within the overall sociotechnical system, which in this case is the organization or business. Some issues that the expert will consider include job design, personnel selection, training, work schedules, and the influence of organizational structure on decisions. The focus of macroergonomics on the relation between human factors and the organization as a system provides a perspective for human factors specialists that can allow them to make significant contributions to the workplace (Kleiner, 2008).

In the present chapter, we examine the social and organizational factors that affect the performance of the organizational system and the individual employee within it. We begin with the individual employee, discussing job-related factors such as employee recruitment and job design. We then move to employee interactions and some of the ways that social psychology can be exploited to the benefit of the organizational group. We conclude with issues pertaining to the organizational structure, such as how groups interact, employee participation in decision making, and the process of organizational change.

We have already discussed many factors that influence worker performance and satisfaction. These involved the physical aspects of the human–machine interface and the surrounding environment, as well as task demands. The core of human factors involves analysis of the psychological and physical requirements for performing specific tasks. Because a job usually involves the performance of many tasks, the human factors expert may be called upon to perform a job analysis.

The broad range of activities demanded by most jobs usually means that employees must possess a similarly broad range of skills. A job analysis is a well-defined and rigorous procedure that provides information about the tasks and requirements of a job, and the skills required for a person to perform the job (Brannick & Levine, 2007).

The job analysis is used to describe, classify, and design jobs. As Sanchez and Levine (2012) emphasize, “Job analysis constitutes the preceding step of every application of psychology to human resources (HR) management including, but not limited to, the development of selection, training, performance evaluation, job design, deployment, and compensation system” (p. 398). Job analysis provides the basis for choosing appropriate selection criteria for prospective employees, determining the amount and type of training that is required for employees to perform the job satisfactorily, and evaluating employee performance. It also is used to determine whether jobs are well-designed ergonomically; that is, whether they are safe and can be performed efficiently. If we determine that a job is not well-designed, the job analysis can be used as a basis to redesign the job. A job analysis, then, can have a profound effect on an employee’s activities.

Any job analysis uses a systematic procedure to decompose a job into components and then describe those components. There are two types of job analysis: work-oriented and worker-oriented (Shore, Sheng, Cortina, & Yankelevich Garza, 2015). A work-oriented job analysis will provide a job description that lists the tasks that must be performed, the responsibilities that a worker in that position holds, and the conditions under which the tasks and responsibilities are carried out (Brannick & Levine, 2007). Techniques that concentrate on the individual elements of specific jobs include, for example, Functional Job Analysis (Fine, 1974), which focuses on the functions performed on the job. Such an analysis might produce functions like supervising people, analyzing data, and driving a vehicle.

A worker-oriented job analysis focuses instead on the knowledge, skills, and abilities required of a person to perform the job. The Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ; McCormick, Jeanneret, & Mecham, 1972), described below, which measures the psychological characteristics of the worker and the environment, is an example of a person-oriented analysis. We might also use a hybrid approach in which work- and worker-oriented analyses are combined (Brannick & Levine, 2007). Any job analysis provides as an end result a job specification or description, which spells out the characteristics of the job and those required of a person holding that job.

Table 18.1 provides an outline of the information that might result from a job analysis. This information might come from several sources (Jewell, 1998). We could start with the records provided by supervisory evaluations, company files, and the U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration’s Dictionary of Occupational Titles. Most of it will come from the people actually performing the job. We can use interviews and questionnaires to determine not only the actual tasks involved in the job we are analyzing, but also the employees’ perceptions about the task requirements and the necessary skills. We can also do field studies and watch people on the job. Finally, we can ask other people who know the job, such as supervisors, managers, and outside experts, to contribute their knowledge to the job analysis data base.

TABLE 18.1

Information about a Job that Can Be Gathered in Job Analysis

•Job Content

•What the person with the job does (tasks, procedures, responsibilities)

•Machines, tools, equipment, and materials used during the performance of the job

•Additional tasks that might be performed

•Expectations of the person performing the job (products made, word standards)

•Training or educational requirements

•Job Content

•Working conditions (risks and hazards, the physical environment)

•Physical and mental demands

•Work schedule

•Incentives

•How the job is positioned in the management hierarchy of the company

•Job Requirements

•Knowledge and information necessary for the person to meet expectations

•Specific skills (e.g., computer programming, data analysis, communication)

•Ability and aptitude (e.g., mathematical, problem solving, reasoning)

•Educational qualifications

•Personality characteristics (e.g., willingness to embrace change, eager to learn)

Clearly, the most valuable source of information is the job incumbent, the person who is doing the job now. If we decide to interview the incumbents, we will get a lot of data from unstructured questions that will be difficult to organize and analyze. An alternative to interviews is a structured questionnaire. This is a set of standard questions that can be used to elicit the same information that we might obtain in an open interview.

One popular structured questionnaire used to conduct job analyses is the previously mentioned PAQ (García-Izquierdo, Vilela, & Moscoso, 2015; McCormick et al., 1972). The PAQ contains approximately 200 questions covering 6 major subdivisions of a job (see Table 18.2). These subdivisions are (1) information input (how the person gets information needed to do the job); (2) mediation processes (the cognitive tasks the person performs); (3) work output (the physical demands of the job); (4) interpersonal activities; (5) work situation and job context (the physical and social environment); and (6) all other miscellaneous aspects (shifts, clothing, pay, etc.). Each major subdivision has associated with it a number of job elements. For each job element, the PAQ has an appropriate response scale. So, for example, the interviewer may ask the incumbent to rate the “extent of use” of keyboard devices on a scale from 0 (not applicable) to 5 (constant use).

TABLE 18.2

Position Analysis Questionnaire (PAQ)

Information Input (35) |

Sources of job information (20): Use of written materials |

Discrimination and perceptual activities (15): Estimating speed of moving objects |

Mediation Processes (14) |

Decision making and reasoning (2): Reasoning in problem solving |

Information processing (6): Encoding/decoding |

Use of stored information (6): Using mathematics |

Work Output (50) |

Use of physical devices (29): Use of keyboard devices |

Integrative manual activities (8): Handling objects/materials |

General body activities (7): Climbing |

Manipulation/coordination activities (6): Hand-arm manipulation |

Interpersonal Activities (36) |

Communications (10): Instructing |

Interpersonal relationships (3): Serving/catering |

Personal contact (15): Personal contact with public customers |

Supervision and coordination (8): Level of supervision received |

Work Situation and Job Context (18) |

Physical working conditions (12): low temperature |

Psychological and sociological aspects (6): Civic obligations |

Miscellaneous Aspects (36) |

Work schedule, method of pay, and apparel (21): Irregular hours |

Job demands (12): Specified (controlled) work pace |

Responsibility (3): Responsibility for safety of others |

Note: Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of items on the questionnaire dealing with the topic. |

Although the PAQ has many positive features, there are jobs for which structured questionnaires such as the PAQ may not be appropriate. For instance, the PAQ is not appropriate for workers with poor reading skills, because it requires a high level of reading ability to understand and respond to the questionnaire items. Also, for some jobs, the PAQ may yield a large number of “not applicable” responses. In these circumstances, we may have to consider an open interview, an alternative questionnaire, or even a different source of information. Regardless of how we collect the information, when we compile the data, we must be able to write job descriptions and specifications that capture the features of the jobs.

You might suspect that proactive job analysis, that is, reliance on job analysis in advance of any problems, correlates positively with organizational performance. This seems to be the case (Siddique, 2004). One study of 148 companies in the United Arab Emirates showed that those organizations that performed proactive job analyses performed better than those that did not, particularly if human resource management was generally prominent in the company. Although these data are only correlational, they suggest that job analysis may be important to an organization’s well-being.

A task analysis performed proactively can provide a basis for job design, whereas one performed retroactively can provide a basis for job redesign. Job design (Oldham & Fried, 2016) will require us to make decisions about the tasks that will be performed by the workers and the way in which these tasks are to be grouped together and assigned to individual jobs (Davis & Wacker, 1987). A properly designed job benefits performance, safety, mental health, and physical health in multiple ways (Morgeson, Medsker, & Campion, 2012).

There are many approaches that we could take to job design. We may want to emphasize the most efficient work methods, the workers’ psychological and motivational needs, their information-processing abilities, and human physiology. In addition, we may want to design jobs from a team perspective, examining teams of workers and their social and organizational needs. Two popular approaches to job design are sociotechnical theory and the jobs characteristics approach (Holman, Clegg, & Waterson, 2002).

Sociotechnical theory is based on the sociotechnical systems concept we described earlier. In this approach, we recognize that desirable job characteristics include sensible qualitative and quantitative demands on the worker, an opportunity for learning, some area over which the worker makes decisions, and social support and credit (e.g., Holman et al., 2002). The jobs characteristics approach more specifically attributes job satisfaction and performance to five job characteristics: autonomy (the extent to which a worker can make her own job-relevant decisions), feedback (information about how well she is performing her job), skill variety (the range of skills she uses in her job), task identity (the degree to which a job requires completion of an entire, identifiable portion of work), and task significance (e.g., Hackman & Oldham, 1976). The extent to which a worker perceives that she has opportunities to use her skills (and not just the extent to which she actually uses those skills) also correlates with job satisfaction (Morrison, Cordery, Girardi, & Payne, 2005).

Both the sociotechnical and the job characteristics approach can contribute to our efforts to design and redesign a job. In the best of all worlds, we should try to design a job well with respect to any approach (Morgeson et al., 2012). However, sometimes alternative approaches may lead to conflicting recommendations. For example, under the sociotechnical approach, the requirement for sensible demands may preclude the autonomy emphasized under the job characteristics approach. When such conflicts arise, they should be resolved by considering which alternative would be best overall for the person doing the job and what we need that person to accomplish in the job.

Few brain surgeons possess the technical skills to fly a Boeing 787, although their level of training is extensive. No matter how smart and well-trained a brain surgeon is, it would not make much sense to hire her to fly a commercial airliner.

An employer’s primary goal is to select individuals whose training is appropriate for the work that a job requires. How does an employer decide the minimum requirements for employment and select the most highly qualified personnel from a pool of applicants? Many of these decisions are made on the basis of a job analysis, which is the first step in personnel selection (Shore et al., 2015). We often use the job specification from a job analysis to develop employment criteria, training programs, and employee evaluations.

To fill a position, an employer must generate a suitable pool of applicants and narrow this pool down to the most qualified individuals. The job description developed from the job analysis can be the basis of a job advertisement and other recruiting efforts. It is often difficult to write a job description that targets the right applicants, and to make that pool of applicants aware of the position.

Recruiting is done either internally or externally. Internal recruiting generates a pool of applicants already employed by the organization. Internal recruiting has a number of advantages. Not only are the difficulties involved in recruiting solved, but internal recruiting is inexpensive, and the opportunity for job advancement provides a significant psychological benefit to employees. External recruiting comprises those activities directed toward the employment of persons not already associated with the organization. External recruiting usually produces a larger pool of applicants, which allows the employer more selectivity.

Selecting applicants from the pool is a screening process. The employer’s goal is to determine who is most likely to be successful at the job, or, in other words, who best matches the job performance criteria defined by the job analysis. Almost everyone has applied for a job, and so you are already familiar with the most common screening device: the application form. This form elicits important information, such as an applicant’s educational background, which the potential employer uses to quickly sort through the applicant pool. After the employer has examined the application forms, he will usually call potential employees in for interviews.

The unstructured personal interview is probably the most widely used screening device (Sackett, 2000). Despite its wide use, the unstructured interview is neither a reliable nor a valid predictor of future job performance. As with any other subjective measure, the biases of the interviewer affect his evaluation of the applicant. We can reduce the effects of biases and increase reliability and validity by using standardized procedures such as tests (van der Zee, Bakker, & Bakker, 2002). However, using unstructured interview information in addition to standardized test information can increase interviewers’ overconfidence in their decisions and reduce the validity of their decisions (Kausel, Culbertson, & Madrid, 2016).

Standardized tests used for employment screening often measure cognitive and physical abilities and personality. Other tests might provide a prospective employer with a work sample. For example, if you apply for a cashier’s position in a store, you will probably be tested on your arithmetic skills. Of all of these tests, it turns out that, for people with no experience, “the most valid predictor of future performance is general cognitive ability” (Hedge & Borman, 2006, p. 463).

No matter what screening method an employer uses, it is considered a “test” by U.S. law. This is because the applicants’ responses to several critical items will determine whether the employer will consider them further. Under U.S. law, application questions and tests that are used as screening criteria must be valid indicators of future job performance. In the U.S., employers are bound by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was revised in 1991 (Barrett, 2000). Title VII prohibits unfair hiring practices. An unfair hiring practice is one where screening of potential employees occurs on the basis of race, color, gender, religion, or national origin. Title VII was necessary to prevent employers from administering difficult, unnecessary exams to Black applicants for the purpose of removing them from the applicant pool, as was also done sometimes when Black citizens attempted to register to vote.

The Civil Rights Act has been expanded over the years. The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 made it illegal in the U.S. to discriminate on the basis of age, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, amended in 2008, did likewise for mental and physical disabilities, and pregnancy.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) established the first guidelines for fair hiring practices in 1966. Even with the Civil Rights Act in place, the EEOC was not legally empowered to enforce Title VII until 1972. The EEOC can now bring suit against employers for violating EEO laws. Discrimination laws similar to those in the U.S. exist for many high-income countries in the world.

A selection procedure “discriminates” or has adverse impact if it violates the “four-fifths rule.” This rule is a general guideline which states that any selection procedure resulting in a hiring rate (of some percentage) for a majority group, such as white males, must result in a hiring rate no less than four-fifths of that percentage for an underrepresented minority group. If a selection procedure has adverse impact, the employer is required to show that the procedure is valid, that is, that it has “job relatedness.” Furthermore, the law requires an affirmative action plan for larger organizations that outlines not only the organization’s hiring plans but also its plans for recruiting underrepresented minorities.

Rarely do new employees come to work completely trained. Usually, their employer will provide them with a training program that will ensure that the employees will become equipped with all the necessary skills to perform their jobs. How training is designed and delivered is of great importance and great concern in an organization.

We must also keep in mind that there is an alternative to designing and providing training programs. We could, instead, hire highly skilled applicants. However, highly skilled applicants require higher salaries and so increase cost. Furthermore, it may be difficult to find applicants with the specific skills required for the job we need done, and even if found, those applicants will often need at least some training to become familiar with all aspects of the specific job they are to perform. So, training programs will always play an important role in organizations.

The more effective training is, the better will be the workforce and the products the organization sells (Salas, Wilson, Priest, & Guthrie, 2006). The systems approach provides a strong framework for instruction and training (Goldstein & Ford, 2002). Using a systems approach to instructional design, we will rely on a needs assessment. This needs assessment will specify the potential learners, the necessary prerequisite knowledge or skills, and the instructional objectives. It will help us design training programs to achieve those objectives, provide criteria against which the effectiveness of the training can be evaluated, and allow us to assess the appropriateness of the training (Johnson & Proctor, 2017).

Many factors can influence the effectiveness of a training program. These factors include the variability of the conditions under which training occurs, the schedule with which training is administered, and the feedback that is provided, as discussed in Chapters 12 and 15. An additional factor is the skill of the trainer. How well does this person teach, motivate, and persuade the employee, and convince the employee that he or she will be successful at the job?

Training can occur on-the-job, on-site, or off-site. Each option has benefits and drawbacks, and we will discuss each in turn.

Employees who receive on-the-job training are immediately productive, and no special training facilities are needed. However, mistakes made on the job by a trainee may have serious consequences, such as damage to equipment needed for production or personal injury.

Because on-the-job training is often informal, we might worry that the employee is not learning correct and safe procedures. There are a number of analyses we might use to evaluate an employee’s learning progress, even in informal settings (Rothwell, 1999). Structured analyses similar to those performed for job analysis, job design, and training needs assessments can be performed for on-the-job training. The results from these analyses will determine whether or not the training program is effective and, if not, highlight changes to the program that we need to make to ensure that trainees are learning appropriate procedures. Overall, evidence indicates that on-the-job training is beneficial for both the workers and their employers, although which of several underlying processes contribute to that benefit remains unclear (De Grip & Sauermann, 2013).

Closely related to on-the-job training is job rotation, in which an employee moves from one work station or job to another on a periodic basis. Some organizations use job rotation to teach employees a range of tasks. This strategy helps ensure that the organization has a pool of employees who are broadly trained, and so operations will not be disrupted if a worker is absent or suddenly quits. In peacetime, the U.S. military employs a form of job rotation (rotational and operational reassignments) in which soldiers and civilian employees receive a new assignment every two or three years. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, this strategy ensures a flexible and quickly deployable source of “manpower” (Wolfowitz, 2005).

Job rotation can develop a flexible workforce whose members are familiar with many of the jobs critical to the functioning of the organization. Job rotation may also provide a way for organizations to learn about employees’ productivities on different jobs and so help determine which employees best match which jobs (Ortega, 2001). For physically demanding jobs, it may also be an effective ergonomic intervention to reduce musculoskeletal injuries (Leider, Boschman, Frings-Dresen, & van der Molen, 2015). However, job rotation may be inappropriate when a high degree of skill is necessary to perform a specific job proficiently.

On-site training occurs somewhere at the job site. The training area may be a room reserved for training purposes, or an entire facility constructed for training purposes, or it might be as informal as the employee lunch room.

On-site training is more controlled and systematic than on-the-job training. However, even though the new employee is drawing a salary, he or she is not immediately contributing to productivity. There may be an additional cost associated with designing and furnishing the training facility.

Off-site training takes place away from the job site. In some organizations, a technical school or university may be contracted to conduct the training sessions. For example, “continuing education” classes, which may be workshops lasting a day or two or classes that meet regularly for several months, give employees the opportunity to learn skills to improve their job performance and earn raises and promotions. Some professional and licensing organizations (such as individual state medical licensing boards and the American Medical Association) require professionals to routinely complete continuing education courses throughout their careers to maintain their license to practice their discipline.

Some employees may need more extended training. In this case, which may arise for people wanting to change their jobs, many companies encourage employees (by covering tuition or promising job advancement) to return to school to become certified or to receive advanced degrees. Distance education, for which employees take courses toward advanced degrees while remaining on-site or at home (Moore & Kearsley, 2012), is a more and more popular way to continue employee education, especially with the growing popularity of web-based courses.

Employee performance in any organization is evaluated both informally and formally. Informal evaluations occur continuously, forming the basis of an employee’s acceptance by his or her peers, the manager’s impressions of the employee, and the employee’s own perception of “belonging to” the organization. Performance appraisal is the process of formally evaluating individual employee performance, and it is usually conducted in a structured and systematic way (Denisi & Smith, 2014). Performance appraisals provide feedback to both the employee and management. They give an employee the developmental information he needs to improve his performance, and they give management the evaluative information necessary for administrative decisions, such as promotions and raises in salary (Boswell & Boudreau, 2002).

A performance appraisal can have several positive outcomes. These include motivating the employee to perform better, providing a better understanding of the employee, clarifying job and performance expectancies, and enabling a fair determination of rewards (Mohrman, Resnick-West, & Lawler, 1989). However, if an employee perceives that the appraisal is unfair or manipulated by a manager to punish the employee, the employee may become less motivated and satisfied, or may even quit (Poon, 2004). Also, relationships among employees may deteriorate, and, if the problems in the evaluation process are widespread, some employees may even file lawsuits. Because performance appraisal can have devastating effects on an employee’s position within an organization, and because an organization needs to have the best workforce possible, managers need to make every effort to ensure that performance appraisals are done well. However, developing an effective performance appraisal procedure is not easy.

An effective performance appraisal begins with an understanding of what it is that must be evaluated. Recall that a manager will have an impression of an employee before the formal performance appraisal, based on his or her daily interactions with the employee. This impression (or bias; see below) may be colored by factors that are not relevant to the employee’s performance, such as the employee’s appearance or personality quirks, which may or may not be relevant to the job. Managers must be very careful not to let these biases impinge on the formal performance appraisal, and to do their best to evaluate employees according to the factors that are relevant for job performance.

A company may choose to evaluate its employees on the results of job performance, such as the number of sales a person accomplished or the number of accidents in which he or she was involved (Spector, 2017). Evaluation on the basis of results sounds attractive, because managers can measure performance objectively, and the effects of any personal bias on the appraisal process will be minimized. However, objective measures may have serious limitations. Usually, objective measures like “number of sales” emphasize quantity of performance, rather than quality, which is more difficult to measure. Consider, for example, two employees whose jobs are to enter records into a data base. One employee completes a great many record entries, but these entries are all very easy. The second employee completes fewer than half of the entries completed by the first employee, but these entries were based on very complicated records that required much more problem-solving skill. Which is the more productive employee?

The results of an employee’s performance may be subject to many factors outside of the employee’s control. For example, a salesperson’s poor sales record could be due to an impoverished local economy. For the data-entry jobs described above, there may not have been as many records this year as there were in previous years. This means that, while it may be appropriate to include some objective measures of performance results in an employee’s appraisal, a fair appraisal will also need to use subjective measures of the employee’s performance.

A good performance appraisal begins with the job description. An accurate job description gives a list of critical behaviors and/or responsibilities that can be used to determine whether an employee is functioning well. In other words, the description distinguishes employee behaviors that are relevant to the job from ones that are not. It also helps identify areas where performance might be improved or where additional training may be needed.

Once we have established the basis on which an employee is to be evaluated, we must decide who is to appraise the employee’s performance and how the evaluation is to be made. Both decisions will depend on the organizational design and the purpose of the evaluation (Mohrman et al., 1989). Appraisers can be immediate supervisors, higher-level managers, the appraisees themselves, subordinates, and/or independent observers. Each appraiser brings a unique perspective that will emphasize certain types of performance information over other types. The choice of appraisal method depends on the reason for the evaluation. If our purpose is to select from a group of employees only a few to receive incentives or to be laid off, then we will use a comparative evaluation scheme in which employees are rank ordered. Usually, however, evaluations are individual, and our goal is to provide feedback that the employee can use to improve his or her performance.

There are several standardized rating scales that we can use for individual performance evaluations (Landy & Farr, 1980; Spector, 2017). The two most popular are the behaviorally anchored rating scale (BARS) and the behavior observation scale (BOS). A BARS performance assessment will typically use several individual scales. A specific “anchor” behavior is associated with each point on a BARS scale to allow the ratings to be “anchored” in behavior. Figure 18.1 shows an example BARS item for “cooperative behavior.” We would rank an employee from 1 to 5 based on her behavior when asked to assist other employees. Associated with each point is a specific behavior, such as “This employee can be expected to help others if asked by supervisor, and it does not mean working overtime,” which rates 3 points on the scale.

FIGURE 18.1An item from a behaviorally anchored rating scale.

The BOS differs from the BARS in that the rater must give the frequency (percentage of time) with which the employee engages in different behaviors, and points are determined by how frequently each behavior occurred. Both the BARS and the BOS represent significant improvements over evaluation methods that have been used in the past, in large part due to their dependence on job descriptions and their decreased susceptibility to appraiser bias.

It is the specter of appraisal error, particularly rater bias, that haunts the process of performance appraisal. As we hinted above, an appraiser who brings his or her bias into the appraisal process risks evaluating an employee unfairly on irrelevant factors. This can potentially alienate that employee and other employees who perceive the process as unfair. While rating scales like the BOS and BARS may reduce this kind of error, these rating instruments may also be biased, or they may play on the appraiser’s biases. For example, the words “average” and “satisfactory” may mean different things to different appraisers. If a scale asks an appraiser whether some aspect of a person’s performance has been below average, average, or above average, this ambiguity will result in very different ratings from different appraisers. A scale may also fail to accommodate all aspects of performance relevant to a job. For instance, a social worker who interacts with children may need to be nurturing and compassionate, but there may not be a scale for “nurturing behaviors” on the rating instrument. Conversely, a scale may be contaminated because it forces the evaluation of irrelevant aspects of performance. The social worker may be forced to work odd hours away from the office, but the scale may ask the appraiser to rate his punctuality or how frequently he interacts with other people in the office. Finally, a scale may be invalid in the same way that any standardized test can be invalid: it may not measure what it was intended to measure.

To some extent, appraisal bias is unavoidable. The appraiser brings a host of misperceptions, biases, and prejudices to the performance appraisal setting. She does not do this intentionally, but because she is subject to the same information-processing limitations that arise in every other situation requiring cognition and decision making. Biases have the effect of reducing the load on the appraiser’s memory. Categorizing an employee as “bad” means that the appraiser does not have to struggle to evaluate each behavior that employee makes; they are all “bad.” This kind of bias, called halo error, is the most pervasive. Halo error occurs when an appraiser evaluates mediocre (neither bad nor good) behavior by “bad” employees as bad, but that same behavior by “good” employees as good. Although appraiser bias cannot be completely eliminated, we can reduce it considerably by extensively training appraisers (Landy & Farr, 1980).

The social and organizational contexts in which the appraisal takes place can also contribute to bias and error (Breuer, Nieken, & Sliwka, 2013; Levy & Williams, 2004). The organizational climate and culture can affect not only the performance appraisal, but also how the appraisal process is conducted and the structure of the appraisal itself. For example, we have already discussed how important it is to evaluate an employee only on the job-relevant aspects of his or her performance. But a loose or informal management structure in an organization may lead to different managers expecting different things from the same employee, resulting in difficulties in determining how best to gather and organize appraisal data, and deciding what feedback to emphasize and what to downplay or ignore.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS AND WORK SCHEDULES

In 2004, Lewis Wolpert said, “It is no coincidence that most major human disasters, nuclear accidents like Chernobyl, shipwrecks or train crashes, occur in the middle of the night.” When we work is an important factor in how effectively we work. An important component of job design is the development of effective work schedules. How well people work with different schedules will depend in part on their biological rhythms.

Biological rhythms are the natural oscillations of the human body. In particular, circadian rhythms are oscillations with periods of approximately 24 hours (Refinetti, 2016). We can trace a person’s circadian rhythms by examining his sleep/wake cycles and body temperature. Some circadian rhythms are endogenous, which means that they are internally driven, and others are exogenous, which means that they are externally driven.

We can track a person’s endogenous rhythms from his or her body temperature, which is easy to measure and reliable. A person’s body temperature is highest in the late evening. It will then decrease steadily until early morning, when it begins to rise throughout the day (see Figure 18.2). This cycle persists even when the person is in an environment without time cues, such as the day/night light cycle (in a polar research station, for example), though it will drift toward a slightly longer period of 24.1 hours (Mistlberger, 2003). Evidence suggests that the systems in the brain that drive the circadian rhythm in body temperature are used by other timing systems throughout the body (Buhr, Yoo, & Takahashi, 2010).

FIGURE 18.2Body temperature throughout the day.

Performance on many tasks, such as those requiring manual dexterity (e.g., dealing cards), or inspection and monitoring, is positively correlated with the cyclical change in a person’s body temperature (Mallis & De Roshia, 2005). Performance levels have a very similar pattern that lags slightly behind the temperature cycle (Colquhoun, 1971). For example, Browne (1949) investigated the performance of switchboard operators over the course of 24 hours and found that it paralleled the circadian temperature rhythm (see Figure 18.3): Operators’ performance improved during the day and then decreased at night.

FIGURE 18.3Delay to make a telephone connection, as a function of time of day.

Long-term memory performance also follows the circadian temperature cycle in a similar manner (Hasher, Goldstein, & May, 2005). However, short-term memory performance follows an opposite cycle: People do better early in the day, with performance decreasing to evening and then increasing during the night (Folkard & Monk, 1980; Waterhouse et al., 2001).

A person’s performance is only partly a function of endogenous circadian rhythms. The performance of more complicated tasks that involve reasoning or decision making does not seem to follow the rhythm of body temperature (Folkard, 1975). When people are asked to complete tests of logical reasoning, they will get faster and faster from morning until early evening, when they will start to slow down. There is a period where both speed and body temperature increase together, but speed starts decreasing much sooner than body temperature. Regardless of a person’s speed, accuracy does not seem to depend on the time of day.

Many of us have experienced jet lag. Jet lag occurs after long-distance flights that cross multiple time zones. Symptoms include difficulty sleeping and decreased performance (Waterhouse, Reilly, Atkinson, & Edwards, 2007). Similar symptoms arise when people try to sleep at an unusual time because of overwork or unexpected demands that kept them from sleeping at their usual time. For instance, if you had to work all night to finish a term paper, you may have tried to sleep during the day after you turned it in. Even though you might have been exhausted, you may have had trouble getting to sleep. It is your circadian rhythms that make it difficult to sleep during the day when your normal nighttime sleep pattern is disrupted.

A person accustomed to sleeping at night has endogenous rhythms that promote alertness during the day rather than drowsiness, and so these rhythms make sleep during the day difficult. Moreover, exogenous factors such as sunlight and increased noise can contribute to daytime sleep disturbance. Even when these factors are eliminated (by using blinds, earplugs, and so forth), people who try to sleep in the morning after their usual nighttime sleep is delayed will sleep for only 60% as long as they would have at night (Åkerstedt & Gillberg, 1982). Good sleep will happen only when it is aligned with the sleep phase of the circadian wake/sleep cycle.

When your standard day/night, wake/sleep cycle is disrupted for an extended period of time, your circadian rhythms will start to adjust. This is because external stimuli, such as the light cycle, entrain your internal circadian oscillations. Eventually you will adapt to the change in your work schedule or new time zone, but this change will take time. On average, it will take about one day per hour difference for your sleep patterns to adjust to a new schedule, but the effects of the change on your work performance may last much longer than that (see below). It will also take at least a week for your circadian temperature rhythm to adjust to an 8-hour phase delay of the type that occurs when a person starts working at night.

The standard work schedule in the U.S. is 5 days a week for 40 hours, and most people work during the day. Some people work more than this and some work less, and some people work strange hours. People who work more than 40 hours a week are on overtime schedules. An overtime schedule may have a person working more than 8 hours a day, or more than 5 days a week. In both cases, people experience fatigue, which can result in decreased productivity relative to that for a 40-hour week. In addition, when a person works extra hours on a given day, these hours typically will be during a phase of his circadian cycle during which his alertness and performance are depressed. This means that there is a tradeoff between a person’s total productivity on an overtime schedule and the quality of the work he does during overtime hours. Although the absolute amount of productivity may increase with an overtime schedule, this occurs at a cost that may not justify the overtime.

Many people who work nights and evenings are shift workers. Shift workers are employed by organizations that must be in operation for longer than 8 hours per day. Many manufacturers operate continuously (24 hours a day), as do hospitals, law enforcement agencies, custodial services, and so on. Approximately 20% of the U.S. workforce is on shift work (Monk, 2003). Organizations in continuous operation usually employ at least three shifts of workers: morning, evening, and night shifts. Compared with the morning shift, accident rates are considerably higher for the evening shift, and even higher for the night shift (Caruso, 2012; Folkard & Lombardi, 2006).

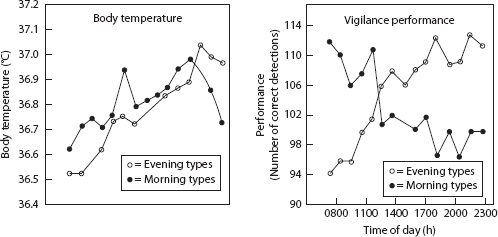

Most people have a preference for one shift over another, but not everyone prefers, say, morning shifts over evening or night shifts. You probably already have a good idea of whether you are a “morning person” or not. These preferences determine not only the kind of shift you might prefer to work, but also how well you can do different tasks (Horne, Brass, & Pettitt, 1980). One experiment asked people classified as morning types and evening types to perform a vigilance task. The results are shown in Figure 18.4, together with their body temperatures throughout the day (from 7:00 a.m. to 12:00 a.m. or midnight). While the number of detected targets steadily increased throughout the day for evening types, it decreased throughout the day for morning types. The morning types had peaks in their endogenous circadian rhythms (measured by body temperature) earlier in the day than the evening types did.

FIGURE 18.4Body temperature and performance, as a function of the time of day, for subjects preferring morning or evening work.

Morning types may be less suited for shiftwork than evening types, because their rhythms do not adjust as easily as those of evening types (Dahlgren, 1988). Young adults show a stronger preference for evening activities, whereas older adults show a strong preference for morning activities (Hasher et al., 2005). This means that if you call yourself a night person now, you can expect to find yourself preferring earlier and earlier activities as you get older. This shift toward being a morning type with age may account in part for the fact that older adults have more difficulty adapting to shift work (Monk, 2003).

Given that it is difficult to adapt to a new schedules, many people generally dislike rotating shift schedules. In a rotating schedule, a person’s days off are followed by a change to a different shift. The problem is that it often takes longer to adjust to a shift change than the time that a person is assigned to that shift (Hughes & Folkard, 1976). One study observed six people working in an Antarctic research station, who were asked to perform various simple tasks after different changes in their schedules. Even 10 days after an 8-hour change in the schedule, their performance rhythms had not yet adapted to match their pre-change rhythms. It may take as long as 21 days after changing to the new shift to completely adapt (Colquhoun, Blake, & Edwards, 1968).

There are a lot of reasons why adaptation to a new schedule takes a long time. Probably the most important reason is that the cycle of daylight and darkness only aligns with the day shift. Consequently, most people work the day shift, which means that the social environment is also structured for the day shift. However, if a person works a fixed schedule, even if it is the evening or night shift, her circadian system will usually adapt completely for that schedule.

Organizations in the U.S. that use shift rotations usually cycle the schedules on a weekly basis. The employees work for 4–7 days on one shift, then switch to another. If we consider how long it takes a person’s circadian rhythms to adapt to a shift change, this is the worst possible rotation cycle. Weekly changes mean that a person’s endogenous rhythms will always be in the process of adapting, and she will be working with chronic sleep deprivation. We could either rotate her shifts more quickly (1–2 days per shift) or more slowly (3–4 weeks per shift; Knauth & Hornberger, 2003). European organizations favor rapid rotation schedules (Monk, 2003). Rapid rotation maintains the worker’s normal circadian cycle. She will experience some sleep deprivation, but not very much, because she can maintain her customary sleep schedule when she is on the day or evening shift, and on her days off.

In contrast, slower rotation schedules of 3–4 weeks allow a person to adapt completely to a new shift before it changes again. While the person spends a week out of each period adapting to the new schedule, there will be 2 or 3 weeks when she is working at her best regardless of the time of day. Slower rotations also tend to prevent any extreme sleep deprivation.

There are two other kinds of schedules we must present: flextime and compressed schedules. Each of these alternatives has its own costs and benefits. In organizations that need continuous operation, flextime and compressed schedules may work well, especially for a workforce that values flexibility.

We have already discussed how different people prefer different work schedules. For this reason, flextime is a popular alternative to the traditional shift schedule (Thompson, Payne, & Taylor, 2015). Flextime schedules allow a significant amount of variability in a person’s working hours (Baltes et al., 1999) and sometimes the workplace. An employee is required to be on the job for some predetermined amount of time each day, for example, 8 hours, and must be on the job during some pre-designated interval, for example, 10:00 a.m.–2:00 p.m. This interval is called core time. The employee has control over all work time outside of core time.

Flextime has the benefit of allowing the employee to coordinate her or his personal needs with work responsibilities. This flexibility in scheduling may in turn reduce stress. For example, a study of commuters working in Atlanta, Georgia, found that those working with a flextime schedule reported less driver stress and time pressure from the commute (Lucas & Heady, 2002). As the employee is allowed to structure the work schedule so that he/she feels best, the employee’s productivity may also increase.

Flextime is used primarily in organizations that are not involved in manufacturing. It is more difficult to allow flexibility like this when the operation of assembly lines and other continuous processes is at stake (Baltes et al., 1999). Because of the difficulties involved in coordinating flextime with continuous manufacturing processes, manufacturing organizations use compressed schedules most frequently as an alternative to traditional shift scheduling.

Compressed schedules require an employee to work 4 days a week for 10 hours a day (Baltes et al., 1999). The U.S. government provides an alternative compressed schedule in which, over a 2-week period, employees work eight 9-hour days and one 8-hour day, and then they have one “regular day” off. Many working couples take advantage of compressed schedules to reduce the amount of time their children need to spend in daycare. Employees who must commute long distances also benefit from the reduction in the time spent driving. Despite these and other potential advantages, fatigue may be a problem for employees working longer days. That is, a person’s productivity or overall performance may be better on a 5-day rather than a 4-day schedule. It is also difficult to synchronize a compressed schedule with rotating shifts, unless the employee is cautious to maintain the same sleep schedule for days off as for days on.

The benefits of flextime and compressed schedules compared with traditional 5-day/8-hour work schedules can be examined scientifically (Baltes et al., 1999). Under flextime schedules, employees were absent fewer days and had higher productivity and higher reported satisfaction, both with their jobs and with their work schedule. Under compressed schedules, employees also reported higher satisfaction with their jobs and work schedules, but they were absent the same number of days and no more productive than they were on a traditional schedule.

Shift work is not easy. People doing shift work often deal with other problems that can affect their job performance (Monk, 1989; 2003). Employees on a fixed night shift are much more likely to try to work a second job, possibly out of financial need, than employees on the day shift. Employees working two jobs will be more tired and stressed, and their performance will suffer as a result. Shift schedules also introduce domestic and social problems. Employees may go for days without seeing their spouses and children. They may feel isolated from their families and community. If these domestic and social factors are not addressed by the employer, they can have a significant adverse impact on productivity.

One way an employer can combat the problems that arise from shift work is to provide adequate employee education and counseling (Monk, 1989; 2003). Employees can be taught how they can facilitate the adaptation of their circadian rhythms with their work schedules. For example, an employee who is working nights on a fixed or slowly rotating schedule needs to be able to identify and strengthen those habits that enable rapid change to and maintenance of a nocturnal orientation. Employees on the night shift also need to learn good “sleep hygiene”: they should maintain a regular schedule of sleep, eating, and physical and social activity, but sleep during the day and be active at night, just as if they were at work.

Employees who learn good sleep hygiene will maximize the amount of sleep that they get, and a training program can emphasize the little tricks that people do who successfully sleep during the day. These tricks include installing heavy, light-blocking shades and curtains to block out sunlight and unplugging the telephone. It is also important that the employee avoids caffeine in the hours before bedtime, which can be difficult when the rest of the world is sitting down to their first cups of coffee. The employee’s entire family has to be trained in the same way, so that they don’t inadvertently sabotage the employee’s efforts to sleep during the day.

The employee’s family needs more training than just in sleep hygiene, however. Because of the domestic and social issues arising with shift work, the employee’s family should be included in any broad training or counseling program. If the entire family is aware of potential domestic difficulties that accompany shiftwork and possible ways to cope with them, the employer can maximize the employee’s chances for a healthy, productive, and satisfying work experience.

In most organizations, employees must interact with at least a few other employees on a daily basis. Sometimes these interactions are minimal, but sometimes the employee may rely on dozens of other people every day.

The type of relationship two people share is often reflected in the distance that they preserve between them. The way that people manage the space around them is called proxemics (Hall, 1959; Harrigan, 2005). The study of proxemics emphasizes how people use the spaces around them and their distances from other people to convey social messages. As robots have become more common, interest has developed in human–robot proxemics, or the impact of physical and psychological distance in human–robot interactions (Mumm & Mutlu, 2011; Walters et al., 2009). Proxemics is important to human factors experts because a person’s proximity to other people (or robots) will affect his or her levels of stress and aggression, and so also his or her performance. Some environmental design recommendations are based on the considerations of personal space, territoriality, and privacy (Oliver, 2002).

Personal space is an area surrounding a person’s body that, when entered by another, gives rise to strong emotions (Sommer, 2002). The size of the personal space varies as a function of the type of social interaction and the nature of the relationship between the people involved. There are four levels of personal space, each having a near and a far phase: intimate distance, personal distance, social/consultative distance, and public distance (Hall, 1966; Harrigan, 2005).

Intimate distance varies from 0 to 45 cm around a person’s body. The near phase of intimate distance is very close, from 0 to 15 cm, and usually involves body contact between the two people. The far phase is from 15 to 45 cm and is used by close friends. Personal distance varies from 45 to 120 cm—within arms’ length. The near phase is from 45 to 75 cm and is the distance at which good friends converse. The far phase varies from 75 to 120 cm and is used for interactions between friends and acquaintances.

Social/consultative distance varies between 1.2 and 3.5 m. At this distance, no one expects to be touched. Business transactions or interactions between unacquainted people occur in the near phase, from 1.2 to 2.0 m. In the far phase, from 2.0 to 3.5 m, there is no sense of friendship, and interactions are more formal. Public distance is greater than 3.5 m of separation. This distance is characteristic of public speakers and their audience. People must raise their voices to communicate. The near phase, from 3.5 to 7.0 m, would be used perhaps by an instructor in the classroom, whereas the far phase, beyond 7.0 m, would be used by important public figures giving a speech.

When the near boundary of a person’s space is violated by someone who is excluded from that space (by the nature of the relationship), the person usually experiences arousal and discomfort. The distance at which a person first experiences anxiety varies as a function of the nature of the interaction. It also is affected by cultural, psychological, and physical factors (Moser & Uzell, 2003). For example, some evidence suggests that older people with reduced mobility tend to have larger personal spaces (Webb & Weber, 2003).

Personal space can also be used as a cue about the nature of the relationship, both by the people interacting and by people watching the interaction. If Person A is unsure whether his acquaintance with Person B has passed into the friendship stage, he can use the distance between himself and Person B to help make this decision. Similarly, if Person A and Person B are almost touching, a third person watching them can interpret their relationship as an intimate one.

The personal distances maintained by members of a group will influence how well group members perform tasks. People will perform better when their distance from other group members is appropriate for the job the group is to accomplish. For example, if the group members are competing with each other, individuals perform better when the distance between them is greater than the personal distance (Seta, Paulus, & Schkade, 1976). Similarly, if the task requires cooperation, people do their tasks better when they are seated closer together, at the personal distance.

A game called the Prisoner’s Dilemma (see Figure 18.5) is often used to study how people cooperate and compete. Two players are “prisoners” accused of a crime (robbery). Each player must decide whether he or she will confess to the police (implicating the other player) or remain silent, without knowing what the other player has decided to do. However, the best choice depends on what the other player has decided to do. If both players choose to confess, they both get reduced but significant sentences (6 years for armed robbery). If both players choose to remain silent, they both get minimal sentences (4 months for petty theft). However, if one person chooses to confess while the other person remains silent, the confessor will go free whereas the silent person will get a maximum sentence (10 years). The game can be easily translated into a monetary game, in which patterns of competition and cooperation result in monetary gains and losses for the two players.

FIGURE 18.5The prisoner’s dilemma.

We can use the Prisoner’s Dilemma to explore how competitive and cooperative behavior evolves as a function of proximity and eye contact between the players (Gardin, Kaplan, Firestone, & Cowan, 1973). Cooperative behavior occurs more frequently when players are seated close together (side-by-side versus across a table). However, when the players can also see each other’s eyes, more cooperative behavior actually occurs when seated across a table. Thus, when interpersonal separation exceeds the personal distance, we can still ensure a degree of cooperation by making sure they can maintain eye contact.

Territoriality refers to the behavior patterns that people exhibit when they are occupying and controlling a defined physical space, such as their homes or offices (Moser & Uzzell, 2003). We can extend the definition of territoriality beyond physical spaces to ideas and objects. Territorial behavior involves personalization or marking of property, the habitual occupation of a space, and in some circumstances, the defense of the space or objects. People also defend ideas with patents and copyright protections.

Territories are primary, secondary, or public, depending on the levels of privacy and accessibility allowed by each (Altman & Chemers, 1980). Primary territories are places like your home. You own and control it permanently. This place is central to your daily life. Secondary territories are more shared than primary territories, but you can control other people’s access to them, at least to some extent. Your office or desk at work could be an example of either a primary or a secondary territory. Public territories are open to everyone, although some people may lose their access to them because of their inappropriate behavior or because they are being discriminated against. Public territories are characterized by rapid turnover of the people who use them.

A person might infringe on your territory by invading, violating, or contaminating it (Lyman & Scott, 1967). Invasion occurs when she enters your territory for the purpose of controlling it. Violation, which may be deliberate or accidental, occurs when she enters your territory only temporarily. Contamination occurs when she enters your area temporarily and leaves something unpleasant behind. Intruders differ in their styles of approach. They can use either an avoidant or an offensive style (Sommer, 1967). An avoidant style is deferential and nonconfrontational, whereas an offensive style is confrontational and direct.

You may defend your territory in two ways: prevention and reaction (Knapp, 1978). Prevention defenses, such as marking your property with your name, take place before any violation occurs. Reactions are defenses you make after an infringement and are usually physical. For example, the posting of a “no trespassing” sign is preventative, whereas ordering an intruder to leave your land at gunpoint is reactive. How intense your reaction will be depends on the territory that was violated. You will feel worst for infringements of your primary territory and least bad for infringements of public territory. When someone infringes on public territory, your response will probably be abandonment—you will leave and go somewhere else.

Your primary territory is important because it is where you feel safest and in control. As a designer, you can exploit this fact by creating workspaces that foster the perception of primary territory, and so create areas where people feel comfortable. Architectural features that demarcate distinct territories for individuals and groups can be built into homes, workplaces, and public places (Davis & Altman, 1976; Lennard & Lennard, 1977). Something as simple as allowing people to personalize their workspace can encourage self- and group-identities.

Personal space and territoriality can be viewed as ways that people achieve some degree of privacy. When someone violates your territory, this can be a source of considerable stress. Similarly, crowding, which can occur in institutions such as prisons (Lawrence & Andrews, 2004) and psychiatric wards (Kumar & Ng, 2001), as well as many other environments, can have a profound effect on your behavior. This happens because crowding leads to limitations on your territory and continuous, unavoidable violations of what little territory you have. We can link crime, poverty, and other societal ills to crowding.

Crowding is an experience that is associated with the density of people within a given area, similarly to the way the perception of color is associated with the wavelength of light. Whereas density is a measure of the number of people in an area, crowding is the perception of that density. Your perception of crowding is also based on your personality, characteristics of the physical and social settings, and your skills for coping with high density. The same density will lead different people to different perceptions of crowding in different settings. For example, culture has a strong influence on the perception of crowding. While no one likes being crowded, and there are in fact no consistent cultural differences in how well people tolerate being crowded, Vietnamese and Mexican Americans tend to perceive less crowding at the same densities than do African and Anglo-Americans (Evans, Lepore, & Allen, 2000).

There are two types of density: social and spatial (Gifford, 2014). When new people join a group, social density increases. When a group of people moves into a smaller space, spatial density increases. However, density is not the same thing as proximity, which is the distance between people. Crowding is directly related to the number of people in an area and inversely related to their distance (Knowles, 1983). When people are asked to rate their impressions of crowding of each photograph, relative to another, of groups that varied in size and distance, the resulting ratio scale values of crowding increased with the number of people in a slide and decreased with their distance (see Figure 18.6). These relationships can be quantified with a proximity index:

FIGURE 18.6Estimates of crowding as a function of number of people (N) and their distance.

where:

Ei |

is the total energy of interaction at point i, or impression of crowding, |

D |

is the distance of each person from point i, and |

N |

is the size of the group. |

In other words, crowding increased as the square root of group size and decreased as a square root of distance.

Crowding produces high levels of stress and arousal. We can measure these responses using blood pressure, the galvanic skin response, and sweating. As stress and arousal increase, these physiological measures increase. Experiments on crowding show that the level of stress that a person experiences in high density situations is a function of the size of her personal space (Aiello, DeRisis, Epstein, & Karlin, 1977). People who prefer large separations between themselves and others are more susceptible to stress in high density situations than those who prefer small separations (see Figure 18.7). This means that individual factors are important in determining whether high density will produce stress.

FIGURE 18.7Physiological stress as a function of preferred distance and crowding.

The Yerkes–Dodson law, discussed in Chapter 9, describes a person’s performance as an inverted U-shaped function of his or her arousal. To the extent that crowding influences arousal, it will impair performance. This effect is greatest for complex tasks (Baum & Paulus, 1987), because the performance of complex tasks suffers more than the performance of simpler tasks at high levels of arousal. One study asked people outside a supermarket during crowded and uncrowded times to complete a shopping list comprised of both physical and mental tasks (Bruins & Barber, 2000). Under crowded conditions, people were less able to perform the mental tasks than the physical tasks, probably because the mental tasks were more difficult. Another study found that when emergency departments in hospitals were crowded, there was an increase in inpatient deaths and small increases in costs and stay lengths for admitted patients (Sun et al., 2013).

People’s behavior in response to crowding can be classified as either withdrawal or aggression. If the option is available, people will try to avoid crowding by escaping from crowded areas. When escape is impossible, a person may withdraw by “tuning out” others or attacking those perceived as responsible for their stress. In these circumstances, aggression is seen as a means to establish control. When a person believes she has no control over her environment, she may stop trying to cope or to improve her situation, choosing instead to passively accept the conditions. This reaction is called learned helplessness.

Many explanations of human responses to crowding emphasize how people feel as though they have lost control in high density situations (Baron & Rodin, 1978). We can distinguish four types of control that a person loses: decision, outcome, onset, and offset. Decision control is the person’s ability to choose his or her own goals, and outcome control is the extent to which the attainment of these goals can be determined by the person’s actions. Onset control is the extent to which exposure to the crowded situation is determined by the individual, and offset control is the person’s ability to remove himself or herself from the crowded situation.

Social survey studies confirm that crowding directly influences a person’s perception of control. Pandey (1999) had residents from high and low density areas of a large city fill out questionnaires asking them about crowding, perceived control, and health. The higher the reports of crowding, the lower control people perceived over their surroundings, and the higher were the rates of reported illness.

Psychosocial factors, such as territoriality and crowding, are prominent in the workplace. We can anticipate problems that might arise from these factors by taking a macroergonomics approach to the analysis and design of offices (Robertson, 2006). Through appropriate design, we can take advantage of the benefits of these factors, avoid their negative consequences, and increase the quality of life at work (Vischer & Wifi, 2017).

We must first systematically evaluate a room or office design from the perspective of those people who will be using it (Harrigan, 1987). We will need to answer questions about the purpose of the room or building, the characteristics of the operations that will take place there, and the nature and frequency of information exchange between people and groups. Who will be using the facility, and what are their characteristics? How many people must it accommodate, and what circulation patterns will facilitate their movements through the space?

After acquiring information about the purpose of the structure, the tasks to be performed, and the users, we will use this information to determine design criteria and objectives. We will do space planning to determine the spaces needed, their size, and how they are arranged. Within the rooms and offices of the building, we must choose what furniture and equipment to provide, as well as the utilities that maintain an acceptable ambient environment. Depending on the size of the workplace, this kind of project will involve not only a human factors engineer but also a team of managers, engineers, human resources managers, designers, architects, and workers.

The office is a workplace where we can apply concepts of social interaction to design problems. The human factors evaluation begins with consideration of the office’s purpose, the workers and other users, and the tasks to be performed in the office. Our goal in designing the office workplace is to make these tasks, and any related activities, as easy to complete as possible.

Facilitating the activities and tasks performed by the office workers is just one dimension of office design, which we refer to as instrumentality (Vilnai-Yavetz, Rafaelli, & Yaacov, 2005). There are two additional dimensions of importance: aesthetics and symbolism. Aesthetics refers to the perception of the office as pleasant or unpleasant. Symbolism is the dimension that refers to status and self-representation. A well-designed office should afford instrumentality, be aesthetically pleasing, and allow appropriate symbolic expression.

There are two kinds of offices: traditional and open. Traditional offices have fixed (floor-to-ceiling) walls and typically hold only a small number of workers. Such offices provide privacy and relatively low noise levels. Open offices have no floor-to-ceiling walls and may hold a very large number of workers. These offices do not provide much privacy, and the noise levels can be quite high.

The primary human factors consideration in the design of traditional offices is the selection and placement of furnishings. One of the earliest studies of office design was published in 1966 by Propst, who reported the results of several years’ investigation into the design and arrangement of office equipment. He obtained information from experts in several disciplines, studied the office patterns of workers that were considered exceptional, experimented with prototype offices, and tested several different office environments. As a result of his investigation, he emphasized the need for flexibility, while pointing out that most office plans of that time relied on oversimplified and restrictive concepts. He also argued that an office needs to be organized around an active individual rather than the stereotypic sedentary desk worker. The furniture and layouts that Propst designed have come to be known collectively as the action office (see Figure 18.8).

FIGURE 18.8The action office.

Propst claimed that the action office would not improve creativity and decision making, but rather, would facilitate fact-gathering and information-processing activities, and so make performance more efficient. Regardless of Propst’s claims, formal evaluations of worker perceptions of the action office showed that the workers greatly preferred the action office design (Fucigna, 1967). After being switched from a standard office to the action office, workers felt that they were better organized and more efficient, that they could make more use of information, and that they were less likely to forget important things. Thus, the action office served the needs of its occupants better than the standard office.

An alternative to the traditional office is the open-plan office. The open office is intended to facilitate communication among workers and to provide more flexible use of space. However, this is at a cost of increased disturbances and distractions (Kim & de Dear, 2013). There are three kinds of open offices: bullpens, landscaped offices, and nonterritorial offices.

The bullpen office is the oldest open-plan office design. It has many desks arranged in rows and columns. Figure 18.9 shows an example of one of several such offices used at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. This arrangement allows a large number of people to occupy a limited space, while still allowing traffic flow and maintenance. However, most workers find a bullpen-style office dehumanizing. Employees of a Canadian company were shifted from traditional offices to open bullpens housing up to nine people (Brennan et al., 2002). The employees expressed deep dissatisfaction that did not abate with time. The employees felt that the lack of privacy actually decreased communication, rather than facilitating it.

FIGURE 18.9Bullpen office.

A landscaped design does not arrange desks in rows, but groups desks and private offices according to their functions and the interactions of the employees (see Figure 18.10). The landscaped design uses movable barriers to provide greater privacy than in the bullpen design.

FIGURE 18.10Blueprint of a landscaped office.

One study investigated the efficiency of the landscaped-style office by surveying employees who worked in a rectilinear, bullpen office about the productivity, group interaction, aesthetics, and environmental description of the office (Brookes & Kaplan, 1972). The office was then redesigned using a landscape plan, in which private offices and linear flow between desks were eliminated. Nine months after the office redesign, they surveyed the employees again with the same questionnaire. Although the employees agreed that the new office looked much better than the old one, they did not judge it to work better. There was no increase in productivity, and the employees disliked the noise, lack of privacy, and visual distractions associated with the landscape plan.

This study illustrates that a major problem in any open-plan office is the presence of visual and auditory distractions. Table 18.3 gives several ways to control the influence of these distractions. We can easily prevent visual distractions by using barriers. Auditory distractions pose a more serious problem. Noise in open offices comes primarily from two sources: building services, such as the air conditioning system, and human activities (Tang, 1997). Clerical workers exposed to 3 hours of low-level noise typical of open offices showed physiological and behavioral effects indicative of increased stress levels (Evans & Johnson, 2000). Some research suggests that when open-plan offices fail, as in the study of Brookes and Kaplan (1972), it is because of noise reflected from hard ceilings (Turley, 1978). While there are some remedies for these kinds of problems, such as sound-absorbent material on ceilings and sound masking devices like white noise generators, we must consider potential problems associated with noise in the early design phases for open office spaces.

TABLE 18.3