Availability Management

The availability of a service is critical to its value. No matter how clever it is or what functionality it offers (its utility), the service is of no value to the customer unless it delivers the warranty expected. Poor availability is a primary cause of customer dissatisfaction. Availability is one of the four warranty aspects that must be delivered if the service is to be fit for use. Targets for availability are often included in service level agreements, so the IT service provider must understand the factors to be considered when seeking to meet or exceed the availability target. This section covers how availability is measured; the purpose, objectives, and scope of availability management; and a number of key concepts.

Defining Availability

ITIL defines availability as the ability of an IT service or other configuration item to perform its agreed function when required. Any unplanned interruption to a service during its agreed service hours (also called the agreed service time, specified in the service level agreement) is defined as downtime. The availability measure is calculated by taking the downtime from the agreed service time as a percentage of the total agreed time.

It is important to note the inclusion of when required in the definition and the word agreed in the calculation. The service may be available when the customer does not require it; including this time in the calculation gives a false impression of the availability from the customer perspective. If customer perception does not match the reporting provided, the customer will become cynical and distrust the reports provided (see Chapter 5).

Keep in mind that the customer experiences the end-to-end service; the availability delivered depends on all links in the chain being operational when required. The customer will complain that a service is unavailable whether the fault is with the application, the network, or the hardware. The availability management process is therefore concerned with reducing service-affecting downtime wherever it occurs. Again, it should be clearly stated in the availability reports whether the calculations are based on the end-to-end service or just the application availability. It is therefore essential to understand the difference between service availability and component availability.

Purpose of Availability Management

The purpose of the availability management process is to take the necessary steps to deliver the availability requirements defined in the SLA. The process should consider both the current requirements and the future needs of the business. All actions taken to improve availability have an accompanying cost, so all improvements made must be assessed for cost-effectiveness.

Availability management considers all aspects of IT service provision to identify possible improvements to availability. Some improvements will be dependent on implementing new technology; others will result from more effective use of staff resources or streamlined processes. Availability management analyzes reasons for downtime and assesses the return on investment for improvements to ensure the most cost-effective measures are taken. The process ensures that the delivery of the agreed availability is prioritized across all phases of the lifecycle.

Objectives of Availability Management

The objectives of availability management include the following:

- Producing and maintaining a plan that details how the current and future availability requirements are to be met. This plan should consider requirements 12 to 24 months in advance to ensure that any necessary expenditure is agreed on in the annual budget negotiations and any new equipment is bought and installed before the availability is affected. The plan should be revised regularly to take account of any changes in the business.

- Providing advice throughout the service lifecycle on all availability-related issues to both the business and IT, ensuring that the impact of any decisions on availability is considered.

- Managing the delivery of services to meet the agreed targets. Where downtime has occurred, availability management will assist in resolving the underlying problem, utilizing the problem management process.

- Assessing all requests for change to ensure that any potential risk to availability has been considered. Any updates to the availability plan required as a result of changes will also be considered and implemented.

- Considering all possible proactive steps that could be taken to improve availability across the end-to-end service, assessing the risk and potential benefits of these improvements, and implementing them where justified.

- Implementing monitoring of availability to ensure that targets are being achieved.

- Optimizing all areas of IT service provision to deliver the required availability consistently to enable the business to use the services provided to achieve its objectives.

Scope of Availability Management

As discussed, the availability management process encompasses all phases of the service lifecycle. It is included in the design phase, because the most effective way to deliver availability is to ensure that availability considerations are designed in from the start. Once the service is operational, opportunities are continually sought to remove risks to availability and make the service more robust. These activities are part of proactive availability management. Throughout the live delivery of the service, availability management analyzes any downtime and implements measures to reduce the frequency and length of any future occurrences. These are the reactive activities of availability management. Changes to live services are assessed to understand any risks to the service, and measurements are put in place to ensure that downtime is measured accurately. This continues throughout the operation phase until the service is retired.

The scope of availability management includes all operational services and technology. Where SLAs are in place, there will be clear, agreed targets. There may be other services, however, where no formal SLA exists but where downtime has a significant business impact. Availability management should not exclude these services from consideration; it should strive to achieve high availability in line with the potential impact on the business of downtime. Service level management should work to negotiate SLAs for all such services in the future, because without them, it is the IT service provider who is assessing the level of availability required when this is a business decision. Availability management should be applied to all new IT services and for existing services where SLRs or SLAs have been established. Supporting services must be included, because the failures of these services impact the customer-facing services. Availability management may also work with supplier management to ensure that the level of service provided by partners does not threaten the overall service availability.

Every aspect of service provision comes within the scope of availability management; poor processes, untrained staff, or ineffective tools can all contribute to causing or unnecessarily prolonging downtime.

Understanding the Effect of Downtime on Vital Business Functions

Availability management must align its activities and priorities to the requirements of the business. This requires a firm understanding of the business processes and how they are underpinned by the IT service. Information regarding the future business plans and priorities and therefore the future requirements of the business with regard to availability is essential input to the availability plan. Only with this understanding of the business requirement can the service provider be sure that their efforts to improve availability are correctly targeted.

The response of the IT service provider to failure can improve the customer’s perception of the service, despite the break in service. The service provider’s actions can show an understanding of the impact of the downtime on the business processes, and an eagerness to overcome the issue and prevent recurrences can reassure the business that IT understands its needs.

Additionally, the process requires a strong technical understanding of the individual components that make up each service, their capabilities, and their current performance. Through this combination of business understanding and technical knowledge, the optimal design can be delivered to produce the required level of availability to meet current and future needs.

When designing a new service and discussing its availability requirements, the service provider and the business must focus on the criticality of the service to the business being able to achieve its aims. Expenditure to provide high availability across every aspect of a service is unlikely to be justified. The business process that the IT service supports may be a vital business function (VBF), and identifying which services or parts of services are the most critical is therefore a business decision. For example, the ability for an Internet-based bookshop to be able to process credit card payments would be a vital business function. The ability to display a “customers who bought this book also bought these other books” feature is not vital. It may encourage some increased sales, but the purchaser is able to complete their purchase without it. Once these VBFs are understood, the design of the service to ensure the required availability can commence. Understanding the VBFs informs decisions regarding where expenditure to protect availability is justified.

It is a business, not an IT decision, what the appropriate availability target of a service should be. However, availability comes at a price, and the service provider must ensure that the customer understands the cost implications of too high a target. Customers may otherwise demand a very high availability target (99.99% or greater) and then find the service unaffordable.

Where very high availability is cost-justified, the design of the service will include highly reliable components, a resilient design, and minimal or no planed downtime.

Having considered the importance of availability to the business, in the following section we examine some of the key availability management activities and concepts that the IT service provider may employ to cut downtime and thus deliver the required availability to the business, enabling it to achieve its business objectives.

Improving Availability

Availability management is comprised of both reactive and proactive activities, as shown in Figure 6.4. The reactive activities include regular monitoring of service provision involving extensive data gathering and reporting of the performance of individual components and processes and the availability delivered by them. Event management is often used to monitor components because this speeds up the identification of any issues through the setting of alert thresholds. It may even be possible to restart the failing service automatically, possibly before the break has been noticed by the customers. (Event management is discussed in detail in Chapter 12.) Instances of downtime are investigated, and remedial actions are taken to prevent a recurrence. The proactive activities include identifying and managing risks to the availability of the service and implementing measures to protect against such an occurrence. Where protective measures have been put in place to provide resilience in the event of component failure, the measures require regular testing to ensure that they actually work as designed to protect the service availability. All new or changed services should be subject to continual service improvement; countermeasures should be implemented wherever they can be cost-justified. This cost justification requires an understanding of the vital business functions and the cost to the business of any downtime. It is ultimately a business, not a technical decision. Figure 6.4 also shows the availability management information system; this is the repository for all availability management reports, plans, risk registers, and so on, and it forms part of the service knowledge management system (SKMS).

FIGURE 6.4 The availability management process

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

The first availability concept we cover is reliability. This is defined by ITIL as “a measure of how long a service, component, or CI can perform its agreed function without interruption.” We normally describe how reliable an item is by stating how frequently it can be expected to break down within a given time: “My car is very reliable. It has broken down only twice in five years.” We measure reliability by calculating the mean (or average) time between failures (MTBF) or the mean (or average) time between service incidents (MTBSI).

Reliability of a service can be improved first by ensuring the components specified in the design are of good quality and from a supplier with a good reputation. Even the best components will fail eventually; however, the reliability of the service can be improved by designing the service so that a component failure does not result in downtime. This is another availability concept called resilience. By ensuring the design includes alternate network routes, for example, a network component failure will not lead to service downtime, because the traffic will reroute. Carrying out planned maintenance to ensure that all the components are kept in good working order will also help improve reliability.

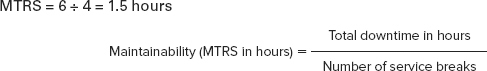

However reliable the equipment and resilient the design, not all downtime can be prevented. When a fault occurs and there is insufficient resilience in the design to prevent it from affecting the service, the length of the downtime that results can be affected by how quickly the fault can be overcome. This is called maintainability and is measured as the mean time to restore service (MTRS). It may be more cost-effective to concentrate resilience measures for those items that have a long service restoration time. To calculate MTRS, divide the total downtime by the total number of failures.

Simple measures can be taken to reduce MTRS, such as having common spares available on site, and these measures can have a significant impact on availability.

ITIL recommends the use of MTRS, rather than Mean Time to Repair (MTTR), because this may or may not include the restoration of the service following the repair. From the customer perspective, downtime includes all the time between the fault occurring and the service being fully able to be used again. MTRS measures this complete time and is therefore a more meaningful measurement.

These concepts are illustrated in Figure 6.5, which shows what ITIL calls the expanded incident lifecycle. This shows periods of uptime, with incidents causing periods of downtime. MTRS is shown as the average of the downtime. MTBF is shown as the average of the uptime.

FIGURE 6.5 The expanded incident lifecycle

Based on Cabinet Office ITIL® material. Reproduced under license from the Cabinet Office.

Each incident needs to be detected, diagnosed, and repaired, and the data needs to be recovered and the service restored. Any method of shortening any of these steps—speeding up detection through event management or speeding up diagnosis by the use of a knowledge base, for example—will shorten the downtime and improve availability. The figure also shows another concept, that of MTBSI; this calculates the average time from the start of one incident to the start of the next. Understanding MTBSI is not required for the examination.

Serviceability

Serviceability is defined as the ability of a third-party supplier to meet the terms of its contract. This contract will include agreed levels of availability, reliability, and/or maintainability for a supporting service or component.