2

THE EVOLVING TRENDS IN INDIA’s FOREIGN ECONOMIC POLICY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PRE-AND POST-LIBERALIZATION PHASES

Antara Acharya

Introduction

One of the most important objectives of foreign policy is to explore prospects for the development of a country through external relations, and to create greater opportunities for material, technological, and monetary interactions. This understanding is premised on the assumption that economic well-being ensures power, security, development and global respect for the country. This also means that no country can afford to ignore the economic rationale of external relations which act as a driving force in foreign policy making. In recent years, this aspect has become even more relevant due to the phenomenon of globalization and the resultant economic liberalization policies adopted by almost all countries in the world. If the Cold War phase was remarkable for the military power struggle and arms race between the ideologically divided groups of countries, the post-Cold War global order is defined by the integration of the global economy and the collective effort by almost all nations to extract maximum benefits from expanding economic opportunities.

This, in a way, has created problems for the conventional notions of sovereignty and security on one hand, while redefining the realm of state responsibility on the other, as non-state actors have emerged as major stakeholders in a closely integrated global economy that is driven by market forces. The economic aspect of foreign policy making has become even more pronounced as free trade agreements have become instrumental aspects of bilateral and multilateral relations. As a result, the foreign economic policy of any government has become a vital parameter for evaluating its success in the realm of external relations.

The foreign economic policy of a country consists of broad outlines concerning its role in the world economy, which are devised to enhance the position of the domestic economy within the broad global framework. The foreign economic policy of a country consists of trade policies, legislations, and positions concerning its economic relationships with other states as well as global economic institutions that ultimately shape its response to the global macrosystem. Although in the age of globalization, the role of the state in the sphere of economy has diminished drastically in comparison to that of the global market forces, nonetheless, foreign economic policy plays an instrumental role in determining a country’s external aswell as domestic economic security and growth opportunities.

The relative importance of the determinants of the foreign economic policy of a country varies in the context of changing trends in the world economy and prevailing ideological orientations. Nonetheless, the basic objective of a country’s foreign economic policy remains the enhancement of economic security and prosperity of its people. The immediate strategies and objectives of a country’s foreign economic policy might vary according to time and space, but the significance of the economic determinants of foreign policy remains constant.

This chapter seeks to establish the significance of India’s foreign economic policy in the process of economic development, especially in the post-liberalization era. The first section addresses the crucial question of whether there ever existed any consistent foreign economic policy (with clearly and explicitly defined goals and strategies) in the pre-liberalization era and develops a simple analytical framework to evaluate the success of India’s foreign economic policy within the framework of a relatively closed economy. The second section focusses on the post-liberalization foreign economic policy of India—its changing objectives, determinants and features. The changing institutional aspects of external economic policy-making have been explored by studying the shifts in economic policies after liberalization. This section also deals with the prospects of India’s foreign economic policy in the context of recent developments in the global economy, specifically the opportunities for global trade under the World Trade Organization (WTO). The overall objective of the study is to explore the trajectory of the evolution of lndia’s foreign economic policy in areas where the shifts in approach have been most pronounced, namely, trade policies, balance-of-payment issues and foreign direct investment. The developments in bilateral economic relations, although extremely significant, have been dealt with only marginally so as to accommodate the study within the scope of the present volume.

India’s Foreign Economic Policy in the Formative Years: The Nehruvian Vision, Mahalanobis Strategy and PL-480

When India attained Independence, the policy-makers were most concerned with issues relating to external security, law and order, domestic economic conditions, democratic institution-building and maintaining political coherence. In the sphere instrumental role in resource procurement, production, and allocation. In practical terms, this meant direct intervention by the government in providing and regulating basic services and creating industrial infrastructure through a strong public sector. There was also a general consensus that economic planning would play a pivotal role in delineating the desired course of economic development to attain the objectives of a welfare state: social justice and social equality. Partha Chatterjee says, ‘The very institution of a process of planning became a means for the determination of priorities on behalf of the “nation”.’1

The Indian Planning Committee2 and the Bombay Plan3 were nearly unanimous regarding the need for some kind of planning or substantial public investment after Independence,4 although there were various other proposals regarding the kind of planning models for India. These options ranged from the Gandhian agrarian economic model to the Nehruvian socialist model. Ultimately, it was Nehru’s planned economic model for modernization through rapid industrialization and a strong public sector that laid the foundations for the country’s economic infrastructure.

It was evident from the pre-Independence position of prominent leaders like Nehru, who incidentally was the main architect of the foreign as well as economic policy for many years, as well as nationalist economic documents like the Bombay Plan that the objective of economic policy in independent India would not be confined to mere economic growth. Its objectives included, the attainment of self-dependence and empowerment of the nation as well. In the initial years after Independence, the main objective was the attainment of self-reliance through inward-looking policies that focussed on building capacity for production with minimum external dependence. This approach had significant implications for the external economic relations of India as well.

Gandhi and Nehru had enormous influence in shaping the economic policy of the country, which set the direction for its foreign economic policy. The Gandhian position was based on a self-reliant and self-sufficient agrarian economy and renunciation of the materialist Western capitalist global order, while Nehru’s progressive position was in favour of rapid industrialization by using modern scientific technology and external aid. The common theme running through both these approaches was the ambivalence regarding dependence on other countries for economic development. However, Nehru was more open to the idea of using external aid, development loans and technological assistance as tools for rapid industrialization.5

It is ironic, however, that although a great deal of attention was being paid to build strong domestic economy, the area of foreign economic policy lacked a coherent long-term strategy and institutional approach. Nehru played an instrumental role in shaping India’s foreign economic policy approach. Nehru was aware of the primacy of economic concerns in shaping the foreign policy making. In one of his speeches in the Parliament, he summed up his views regarding the importance of economic concerns in shaping India’s foreign policy thus:

Ultimately, foreign policy is the outcome of economic policy, and until India has properly evolved her economic policy, her foreign policy will be rather vague, rather incoherent and rather groping … I regret that we have not produced any constructive economic scheme or economic policy so far…. Nevertheless we shall have to do so and when we do so, that will govern our foreign policy more than all the speeches in this house.6

Nehru also tried to segregate economic considerations from political motivations, keeping India’s developmental concerns above other ideological considerations while shaping bilateral relations with other countries. In fact, Nehru was keen on cultivating economic relations with other countries irrespective of the ongoing Cold-War power-bloc politics. He said: ‘While remaining quite apart from power blocs … our relations can become as close as possible in the economic or other domain with such countries with whom we can easily develop them.’7 Thus, under Nehru, India’s economic diplomacy was meant to be premised on a rational assessment of the existing situations.

Ironically, the institutional framework for conducting foreign economic policy was lacking in the initial years of Independence. The Ministry of External Affairs had very little to do in the matters of economic diplomacy, and the ministries dealing with specific economic aspects dealt with the economic aspects of India’s foreign relations. Although the ministry was in charge of all the aspects of India’s foreign relations, it was not sufficiently specialized to deal with foreign economic relations.8

The approach adopted by the Government of India regarding external economic relations in the post-Independence phase was shaped by various factors. Most important among these was the immediate political and economic situation the country found itself in. On the one hand, the foundations of the post-Second World War global economic order were being laid through the introduction of the Bretton Woods institutions and the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of war-torn Europe and, on the other, the nascent democracy in India was faced with the legacies of colonialism, and the problems associated with redefined territorial configuration.

The post-Independence phase in India was one of the most exciting yet challenging phases in the development of collective synergies for nation-building. The problems arising with the trauma of Partition and its economic repercussions9 apart, the collective enthusiasm for rebuilding the nation was driving force behind the economy. Therefore, building the infrastructure for rapid development and self-reliance. This mammoth task was not possible without external assistance. At the same time, it must be noted that India was not the recipient of assistnce for massive national rebuilding on the lines of the Marshall Plan, which had been created to rebuild the war-wrecked economies of Western Europe. The primary reason behind this was the apprehension among the Western donor countries regarding India’s capability to channel the aid into productive capital assets.10 This point was further emphasized by P.N. Dhar, a former director of the Institute of Economic Growth, who held that a ‘critique of government’s policies will certainly indicate that sometimes resources have been used less productively than was ideally possible.’11 This often resulted in under-utilization of resources. This problem was further complicated by the absence of a formal machinery in India to catalyze multinational collaboration needed for effective aid giving, unlike Europe.12 As a result, the World Bank acted as a vital link in channelling foreign assistance to India.

Nehru and the other policy-makers were aware that unless India became self-sufficient in basic requirements and built industrial infrastructure on modern scientific bases, there was no hope for its rapid progress. In part, this realization was also influenced by the Keynesian economic principle of creating more jobs through public investment in order to increase consumption and expand the economy. Nehru’s economic vision was also influenced by the ideological principle of socialism as a means to provide greater equality of opportunity, social justice, and equitable distribution of wealth, and ending the socioeconomic disparities generated by feudalism and capitalism.13 All these factors greatly influenced in India’s early foreign economic policy approach.

So far as the external economic relations were concerned, they were conducted with four primary objectives:

- Securing foreign loans or aid to meet immediate challenges of food short-age and basic requirements,

- Receiving foreign assistance in the area of competence-building and infra-structure development in the form of loans or technical assistance,

- Regulating foreign trade in concordance with the broad foreign policy objectives, and

- Playing an important role in the multilateral institutions and forums for developing economies.

Foreign Aid

OECD’s Development Assistance Committee has defined foreign aid as ‘the flow of long-term financial resources to the least developed countries and multilateral agencies’.

The position of the government regarding external aid was made clear by Nehru. India was open to such assistance, provided they did not contain any hidden purpose. He said the Constituent Assembly in March 1948, ‘We want the help of other countries; we are going to have it and we are going to get it too in a large measure’.14

The First Five-Year Plan document also reiterated the above position in clear terms. It observed that, ‘In these early stages of development further external assistance would certainly be useful’.15 In another important speech in the Lok Sabha, Nehru said:

Other countries realize that we cannot be bought by money. It was then that help came to us; we shall continue to accept help provided there are no strings attached to it and provided our policy is perfectly clear and above board and is not affected by the help we accept… If at any time help from abroad depends upon a variation, however slight in our policy, we shall relinquish that help completely and prefer starvation and privation to taking such help; and, I think, the world knows it well enough.16

Similar views about the importance of external assistance in the process of nation-building in the Third World countries was expressed by the final communiqué of the historic Asian-African Conference in Bandung, in which India played an important role. It stated that

The proposals with regard to economic cooperation within the participating countries do not preclude either the desirability or the need for cooperation with countries outside the region, including the investment of foreign capital. It was further recognized that the assistance being received by certain participating countries from outside the region, through international or under bilateral arrangements, had made a valuable contribution to the implementation of their development programs.17

The point that emerges from the above views was that India was to be guided not so much by ideological Cold-War bloc politics as by rational assessment of the requirements of the country in the realm of assistance. Therefore, India showed similar interest in receiving assistance from the USA as well as the USSR and the Eastern European countries.18 In the early phase, India also received assistance from various international organizations like the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Development Assistance, the Ford Foundation, the OPEC Special Fund, the European Economic Community (EEC) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD).19

The foreign assistance flow to India for the first Plan was estimated at Rs 156 crore, or 10 per cent of the draft plan outlay of Rs 1,493 crore. Most of this assistance came from Anglo-American sources.20 The most important among these was the US economic and technical assistance to India programme under the Mutual Security Act. It provided a grant of $153 million to increase foodgrain production and raise the living standards in the rural areas.

However, India’s stand on external aid changed drastically during the later decades under the influence of the growing collective assertion of rights by the developing countries. Former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in a speech delivered at the United Nations General Assembly on 14 October 1968 said, ‘Aid is only partial recompense for what the superior economic power of the advanced countries denies us through trade.’21

Food Imports

Food security was one of the most crucial issues that India faced after Independence. Per capita foodgrain availability at the time of Independence was about three-fourths of what it had been at the turn of the century.22 India was an exporter of foodgrains (except cereals) by the late 1930s and early 1940s.23 The situation worsened due to the outbreak of the Second World War, the Bengal Famine of 1941–42 and the massive refugee influx after the Partition. From 1943 onwards, import of foodgrains became an exclusive monopoly of the State. After Independence, the government appointed a second Foodgrains Committee in September 1947. The report of this committee blamed the prevailing food policy and suggested the reduction of food import dependence to tackle the problem. Despite such realizations, India had to depend heavily on external assistance for food, especially from the USA. In fact, in 1951, the wheat loan was the first major US economic assistance programme for India.24 The surplus agricultural commodities programme under the Agricultural Trade and Development Act of 1954 and Public Law 480 of the USA played an important role in meeting the food crisis in India till the introduction of the Green Revolution, which made the country self-sufficient in foodgrain production.

Trade as a Vehicle of Growth

In the pre-Independence phase, India had been more of a ‘trade-free market’ regime.25 The colonial phase had witnessed a close integration of the Indian economy with the British economy, although in largely asymmetrical terms. A major part of India’s external trade relations in the immediate post-Independence phase was also confined to Britain and its former colonies or the USA.26 In the sphere of foreign trade, the share of imports was far higher than exports, creating an enormous balance-of-payment deficit for the country.27 In fact, the balance of payment problem was to haunt the Indian economy for many years to come.

Foreign Trade

At the time of Independence, industry and mining accounted for only about 17 per cent of the national income.28 Though in the subsequent years emphasis was laid on rapid industrialization of the country through public investment, prospects for foreign capital and industry were not totally eliminated. The Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948 recognized the value of foreign capital in the process of industrialization, but adopted a cautious approach by stressing the need to regulate it in the national interest.29 India had a relatively comfortable position of foreign exchange reserves by the late 1940s, which was further boosted by the Korean War boom that affected commodity prices.30 The first plan was also largely indifferent to export-or import-related issues. It stated: ‘In periods of relatively easy foreign exchange supplies, the need for export promotion will be less evident.’31 In context of foreign trade, it further held that,

The expansion of trade has, under our conditions, to be regarded as ancillary to agriculture and industrial development rather than as an initiating impulse in itself. In fact, in view of the urgent needs for investment in basic development, diversion of investment on any large scale to trade must be viewed as a misdirection of resources.

The development strategy of the first Plan adopted the principles underlying the Harrod-Domer growth model that highlighted the role of domestic savings and marginally stressed on foreign aid for residual needs.32 Thus, there was no major restriction on foreign import or export during the first Plan period. For example, India was a major supplier of manganese ore to the USA, and its export drastically rose from Rs 1.8 crore in 1948–49 to Rs 24.2 crore in 1953–54.33 Regarding foreign private enterprise, Nehru held the opinion that

[The] Government would expect all undertakings, Indian or foreign, to conform to the general requirements of their industrial policy. As regards existing foreign interests, government do not intend to place any restrictions or impose any conditions which are not applicable to similar Indian enterprises. Government would also so frame their policy as to enable further foreign capital to be invested in India on terms and conditions that are mutually advantageous … foreign interests would be permitted to earn profits, subject only to regulations common to all.34

On 6 April 1949, a statement promised equal treatment to Indian and foreign businesses, no restrictions on profit remittances or withdrawal of foreign capital and fair compensation in the event of nationalization.35 Gradually, by the second and the third Plan periods, the approach of the government regarding foreign trade gradually hardened into export pessimism, and it began to insist on import substitution.

In a way, trade, largely considered to be the engine of growth, was not given due significance in the second and third Plans that largely reflected the Mahalanobis approach. Certain clarifications about the Mahalanobis plan needs to be made at this point. It is generally believed that his growth model was based on the principle of a closed economy, with exclusive emphasis on heavy industries for building capital base and achieving maximum self-dependency. This would have had the added advantage of spreading the benefits of rapid growth to other sectors of the economy. It should be noted here that this was a technical model and was neutral to the ownership of productive resources. Moreover, foreign trade did not figure prominently in the model.36 The methods adopted by the planners to eliminate dependency on the outside world have been described by Nayyar as ‘attempted autarky’ or ‘export fatalism’.37 In the long run, this gave rise to export pessimism. Sukhomoy Chakravarty38 asserts that it was due to the realization that it was not possible to achieve significant increase in export earnings in the short run with the given economic infrastructure.39 It was considered more prudent to concentrate on building strong domestic foundations of industries and increasing production, before opening the Indian economy to the world. Although insufficient production and domestic consumption are generally presented as possible explanations for export pessimism, Chakravarty blamed the lack of political will for inadequate utilization of India’s opportunities in the global market.40 Overall, the focus of the Mahalanobis strategy was on diversification of the export basket in the direction of manufactured goods, while increasing employment opportunities and demand at the same time.

The strategy of import substitution did not yield the desired results as the process of import substitution proved to be far more difficult in the capital goods sector. The need was then felt to earn more foreign exchange through export promotion. But these efforts were undermined by the system of tight import controls, tough trade restrictions and close regulation of foreign exchange transactions. Economist Jagdish Bhagwati has described the situation existing at that phase thus:

[There was] a tight control over imports through import restrictions, continuous short-age of raw material imports, careful screening of investments that call for imported equipment, and a generally uneasy feeling that exports need to be pushed up while little is being done to bring this about.41

By the time the Third Five-Year Plan was being formulated, it was realized that exports had to be increased in order to receive more foreign exchange and reduce dependence on external aid. Thus, the Third Five-Year Plan observed that ‘one of the main drawbacks in the past has been that the programme for exports has not been regarded as an integral part of the country’s development effort under the Five-Year Plans.42 Therefore, export promotion was a major ingredient of the development strategy under the third Plan. Various export promotion measures were taken and export promotion institutions were established. Export promotion councils, the Export Credit and Guarantee Corporation, the State Trading Corporation and export houses, were important institutional arrangements set up by the government to promote exports. Procedural simplification was sought through measures like tax concessions and credit facilities, quality control measures and import entitlement schemes. By 1964, India started exploring possibilities for encouraging joint industrial enterprise in other developing countries.43 A set of guidelines was prepared to set up joint industrial ventures abroad.44

Technological Assistance

An important aspect of foreign collaboration that gradually gained prominence in the pre-liberalization phase was the area of technological assistance and aid for setting up heavy industries, irrigation facilities, railway networking and electricity generation. The US was an important contributor in this regard. The Second Plan period began in 1956 with an increased need for capital imports. Besides the PL-480 Foodgrain Assistance Programme, American assistance was also channelled through the Development Loan Fund, established in 1957.45 It provided the much-needed capital for power projects, manufacturing industries and other developmental projects. In January 1958, the US announced a loan of $225 million to meet the crucial requirements of the second Five-Year Plan. In July 1959, the World Bank provided a $10 million loan to India. The total external assistance received by India till June 1959 amounted to Rs 1416 crore. However, the bulk of foreign investment in the private sector was concentrated in trading activities in petroleum. India also continued to receive technical and economical assistance under the Colombo Plan of Technical and Economical Cooperation. Thus, India received assistance from Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Borrowings from IBRD between 1931 to 1956 amounted to $125 million. This made India the single largest borrower from the bank. Loan assistance of about Rs 233 crore the from the USSR, West Germany and the UK helped in financing three major steel plants at Bhilai, Rourkela and Durgapur. Assistance from Canada and Australia were largely in the form of loans in wheat and manufacturing goods. Norway helped in joint development of fisheries, Japan in purchase of industrial plants and machinery, Czechoslovakia in the establishment of forge foundry and Romania in developing machinery and skills for oil refineries.

During the Plan periods, several donor countries and aid agencies came forward to assist India in achieving rapid development. While most of the American aid came in the areas of agriculture, food security, rural development and infrastructure, Germany, the USSR and the Eastern European countries helped in industrial development.46 The share of the different countries and agencies during the Third Five-Year Plan is shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 External Assistance to India for the Third Five-Year Plan

| Assisting country/Agency | Total(in Rs crore) |

|---|---|

| USA | 1268.9 |

| IBRD and IDA | 423.1 |

| West Germany | 308.6 |

| UK | 254.4 |

| Japan | 138.2 |

| Canada | 117.3 |

| USSR | 104.3 |

| All | 2943.7 |

Source: S. Mansingh and C.H. Heimsath, A Diplomatic History of Modern India, Calcutta: Allied Publishers, 1994, p. 378.

Of the different forms of collaborations with foreign enterprises, the ‘package deal approach’ appeared to be the most attractive. The steel plants at Bhilai, Rourkela and Durgapur were set up with private and public investment from the respective assisting countries. This saved the government from getting into the details of the technical aspects of production, procuring raw materials and training the personnel. However, a major drawback of such an arrangement was that it made India totally dependent on the assisting country. This was criticized in the Estimate Committee’s report on the steel ministry in 1959. In the case of the Durgapur steel plant, which was being built with British assistance, it held that it was not ‘in the interest of the country to enter into such package deals’.47

An interesting observation, which can be made from the above pattern of external collaboration, is that during the late 1950s and the 1960s, India was not opposed to the idea of inviting foreign private investment. The third Plan showed a distinctive change in the attitude of the planners towards foreign trade and it was realized that export promotion was a crucial component of economic development. In 1959, India and the US entered into an agreement to facilitate dollar convertibility. With many West European countries, agreements were reached to avoid double taxation. Tax holidays and fair dealing on profits and repatriation helped to improve the investment climate in India. Manufacturing, petroleum, plantation, and mining were a few areas that attracted foreign investment. By the end of 1961, the foreign-controlled assets in India formed slightly more than two-fifth of the total large-scale private sector investment.48 According to the financeministry, ‘foreign-associated issues accounted for per cent of all authorized capital (1951–63) and for 59 per cent of authorized capital in the private sector (1957–63)’.49

According to Deepak Nayyar, this change in attitude was a deliberate attempt to correct past mistakes.50 Thus, India’s overall export returns rose by over 7 per cent per annum in the early 1960s and, from 1960 to 1965, India’s exports to USA grew by almost 60 per cent.

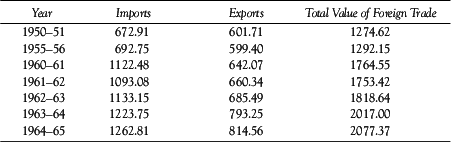

Table 2.2 illustrates the import–export volumes of India between 1950 and 1965:

Table 2.2 Foreign Trade Volume of India (In Rs crore)

Source: India 1966; p. 325; S. Mansingh and C.H. Heimsath, A Diplomatic History of Modern India, Calcutta: Allied Publishers, 1994.

Table 2.3 presents a statement of major foreign investments in 1955 and 1960.

Table 2.3 Foreign Investment in India (1955 and 1960) (In Rs crore)

| Country/Agency | Year | |

|---|---|---|

1955 |

1960 |

|

| Great Britain | 376.8 |

446.4 |

| USA | 39.8 |

112.7 |

| Switzerland | 6.6 |

8.9 |

| West Germany | 2.5 |

6.8 |

| Others (including World Bank) | 30.4 |

115.7 |

| Total | 456.1 |

690.5 |

Source: Ibid., p. 382.

However, a major condition for almost all private foreign investment was that at least 51 per cent control of these enterprises had to remain with the Indians, and they were also under obligation to replace foreign technical personnel at the earliest.

A major step in the process of liberalizing the foreign trade regime in India was taken in 1966 in the form of devaluation of the rupee by around 40 per cent. This move was largely due to the inflation resulting from the war with China in 1962, and the monsoon failure that caused a sharp decline in agricultural output in 1965–66 and 1966–67. The domestic implications of these developments were felt in the form of temporary abandonment of the five-year planning process and greater government focus on the agriculture sector. For the purpose of the present study, the focus will be on the impacts of these developments in the area of foreign economic relations.

Looking at the area of trade-related laws, three important enactments were crucial in determining the foreign investment potential in India after 1965. These were the Monopoly and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act of 1969, the Indian Patents Act of 1970 and the Foreign Exchange and Regulation Act (FERA) of 1973. The first enactment set up the MRTP Commission that, in effect, evaluated the export commitments of the large firms to approve their capacity expansion prospects. The Patents Act 1970 provided for product patents in all areas except food, pharmaceuticals and chemicals where only process patents were given. This hurt the interests of MNCs manufacturing chemicals and pharmaceuticals as it allowed domestic companies to produce cheap drugs. Finally, FERA compelled the foreign firms to dilute their stake and foreign branch companies were compelled to Indianize their shareholding. These provisions, along with the cumbersome import licence regime51 gave birth to the (in)famous ‘licence raj’, the breeding ground for corruption. Needless to say, these enactments did not emit very positive signals about the foreign investment climate in India.52

Balance-of-Payments Problem

An important concern for Indian foreign economic relations prior to the liberalization era (with exceptional years) was the balance-of-payments problem. This problem became especially acute after the second Five-Year Plan. A major reason for this was the export pessimism that had gripped the policy-makers. Between 1956–57 and 1975–76, there was a phase that Dr Bimal Jalan has characterized as the ‘period of fiscal conservatism’, when the fiscal deficit constituted less than 6 per cent of the GDP53 Public savings rose from 1.9 per cent in 1956–57 to 4.2 per. cent in 1975–76.54 During this period India’s balance-of-payments problem was moderately high. The years 1976–77 to 1979–80 stood out as the golden years for India’s balance-of-payments situation when the country had a current account surplus of 0.6 per cent of the GDP Comfortable food stock and foreign exchange. situation and remittances from the Indians working in the booming Gulf region were some of the factors responsible for this. As the BOP situation improved, the government also introduced some measure of import liberalization.

The most important measure was the extension of Open General Licence (OGL) provisions to all items except those specifically restricted or banned. However, the second oil shock of 1979–80, sharp decline in foodgrain production and spurt in inflation led to an increase in the trade deficit from Rs 2,200 crore in 1,978–79 to Rs 6,000 crore in 1980–81.55 This compelled India to take a 5 billion loan from the IMF under the Extended Fund Facility in 1981. Thus, this balance-of-payment crisis was met through the concessional assistance from an external source on market terms. The balance-of-payments problem in the 1980s was also indicative of a drawback of the kind of import liberalization policy being pursued in India. (During this phase, the liberalization policy supported massive imports and the growth in imports was financed largely by commercial borrowings.) The mismatch between the free import policy and limited potential for export expansion led to huge deficits in import spending and export earnings. This was an important reason behind India’s balance–of–payments crisis in the 1980s. India’s declining share in the total world exports from 0.98 per cent in 1965 to 0.44 per cent in 1990 was indicative of the problem.56 In fact, an important cause for the adoption of the liberalization policy in 1991 was the deteriorating balance-of-payments situation of Indian economy. This became evident from the Eighth Plan document’s assessment of the situation:

The balance of payments situation has been continuously under strain for over almost a decade. During the Seventh Plan period, the ratio of the current account deficit to GDP averaged 2.4 per cent—far above the figure of 1.6 per cent projected for this period in the plan documents. This deterioration in the balance of payments occurred despite robust growth in exports in the last three years. The already difficult balance of payments situation was accentuated in 1990–91 by a sharp rise in oil price and other effects of the Gulf War. With the access to commercial borrowings going down and the non-residents deposits showing no improvements, financing the current account deficits had become extremely difficult. Exceptional financing in the form of assistance from IMF, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank had to be sought. While the immediate problems have been resolved to some extent, it is imperative that during the Eighth Plan steps are taken to curb the fundamental weakness in India’s balance of payments situation so that it does not cause serious disruption to the economy.57

In fact, the worsening balance-of-payments situation was a major trigger for the gradual process of economic reforms that started in the early 1980s with the delicensing of investment limits for a large number of industries, and the inclusion of more exportable items on the OGL. In hindsight, the biggest drawback of this approach was that it created an imbalance between import and export growth patterns. While the relaxation in import policies led to a higher import of raw materials for manufacturing, the sluggish export scenario coupled with exogenous economic constraints put a severe burden on India’s foreign reserves and created major problems for the Indian economy. Another important object of criticism in this phase was the highly restrictive policy towards foreign investment. The scope for foreign investment in India was restricted in terms of areas of investment as well as procedural formalities. Besides, the foreign investors were allowed only a minority equity participation of 40 per cent. Thus, the share of foreign direct in-vestment (FDI) in India’s gross capital formation was only 0.2 per cent as against the average of 6.1 per cent for the developing countries as a group.58 This led tothe adoption of the liberalization policy in 1991 which was a watershed event and started a new chapter in the evolution of India’s foreign economic policy.

The Major Trends in India’s Foreign Economic Policy Since 1991

An enormous amount of literature exists on the various factors that led to the adoption of the liberalization policy in India in 1991, the summary of which is beyond the scope of the present paper.59 However, it should be noted that the two main factors that led to the failure of the liberalization attempts made in 1980 were the inability to raise the export volumes to match the increase in imports resulting from the liberalization process and the absence a of prudent fiscal discipline machinery to avoid the foreign exchange crisis. Therefore, these factors were important concerns for the liberalization policy adopted in 1991.

The present section deals primarily with,

- the changes brought about by the liberalization policy in the area of foreign economic policy,

- the changes brought about in the institutional approach in conducting economic diplomacy in context of globalization,

- the emerging issue areas that dominate India’s foreign economic policy concerns, and

- the challenges facing India’s foreign economic policy in the present context.

Needless to say, the liberalization policy had a major impact on India’s foreign economic policy. The basic parameters that had defined India’s approach towards private capital, trade policy, foreign investment norms, import–export condition-alities, external assistance and global economic institutions were all redefined.60

The most visible impact of the reform process could be seen in the area of industrial deregulation. Industrial licensing has been abolished for all industries (except for specified areas) and investment decisions no longer depend on governmental approval. Monopoly restrictive laws have been amended to allow more private participation and greater investment.

In the area of trade liberalization, quantitative restrictions on import and export have been removed from almost all products, and efforts have been made to raise the country’s trade volume. The few noteworthy trade promotion methods include the establishment of export promotion councils, special economic zones, agricultural export zones, and trade facilitation centres, and the reduction of transaction costs. Another method for promoting bilateral trade is becoming in-creasingly popular and important is through the free trade agreements that India has signed with an increasing number of countries. Besides, as an active member of the World Trade Organization, India has also emerged as an important advocate of the rights of the developing countries under global free trade arrangements. The Exim policy of 1997–2002 was remarkable in its efforts to deregulate and simplify trade procedures, and scrap quantitative restrictions in a phased manner.

In this context, the foreign trade policy of 2004–2009 also deserves mention. It takes an integral view of India’s foreign trade scenario, and provides a roadmap for its development. It recognizes agriculture, handlooms and handicraft, gems and jewellery, and leather and footwear as thrust areas for export expansion. Special measures have been taken to promote agricultural exports under the Vishesh Krishi Upaj Yojna. Duty-free import of agricultural capital inputs has been facilitated under the Export Promotion Capital Goods scheme. A new scheme to accelerate growth in exports called ‘Target Plus’ has been introduced. To make India a global trading-hub, a ‘Free trade and warehousing zone’ scheme has been introduced. It seeks to create trade-related infrastructure with the freedom to carry out transactions in convertible currencies. These measures seek to enhance the international competitiveness and promote India’s share in international trade, which is currently abysmally low at less than one per cent.

A crucial and controversial area that has an enormous implication for India’s foreign economic policy is foreign investment. The government has adopted a very cautious and gradualist approach in allowing FDI into India. Many concessions were given to the foreign investors. In order to encourage FDI inflow, the restrictions of 40 per cent equity under FERA was raised to 51 per cent. However, it was allowed only in select high priority areas, but gradually, its realm has expanded to cover almost all the sectors of the economy, including infrastructure, telecommunications, civil aviation and media. In 1991, the industrial approval system in all industries was abolished except for 18 sensitive areas. In 34 priority industries, upto 51 per cent FDI was approved through the automatic route. Technology transfer was not made a necessary prerequisite for FDI approval.

A Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) was set up in 1992 to approve FDI proposals. Accordingly, FERA was also amended to facilitate FDI inflow. In 2005, FDI of upto 100 per cent was permitted in petroleum products marketing, oil exploration, petroleum products pipelines, scientific and technical magazines and journals and upto 74 per cent in private sector banking, as well as the telecom sector. The Global Competitiveness Report 2003–04 by the World Economic Forum ranked India at 41st place on barriers to foreign ownership, as against 81st for China.61 According to the World Investment Report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), FDI in the Indian economy has risen from $.40 billion to $4.27 billion.62

The aggregate inflow of non-resident Indian (NRI) deposits in various schemes reached $14.3 billion by the end of 2003–04. This was the result of the various policy initiatives taken to facilitate inflow of NRI deposits. However, the outflow of NRI deposits also recorded a 47 per cent increase to reach $10.6 billion in 2003–04 as against $7.2 billion in 2002–03.63

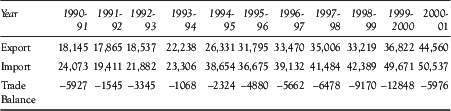

Table 2.4 looks at the foreign investment inflow pattern in India between 1990 and 2000.

Table 2.4 Foreign Investment Inflow in India; 1990–2000 (US $ million)

Source: Sharanjit Singh Dhillon and Lalita Kapoor, ‘Foreign Portfolio Investment and Indian Capital Market after Liberalisation’ in P Arya and B.B. Tandon (eds), Economic Reforms in India: From First Generation and Beyond, New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications. 2003, p. 581.

Another important component of the foreign institutional investment concerns the policy changes regarding the capital market and portfolio investment. The government has adopted a cautious approach in this matter. The major reforms introduced were the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), market-determined allocation of resources, dematerialization and electronic transfer of securities (demat), introduction of rolling settlement, trading in derivatives and risk management and the introduction of screen-based trading system. Besides, Indian companies were allowed to raise funds from abroad through the issue of ADRs, GDRs and foreign currency convertibility bonds. Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) were allowed to invest in all types of securities, and their investments enjoyed full capital account convertibility.

A major area of concern for the Indian economy was the balance of payments scenario. This was an important concern for the economy in the pre-liberalization phase as well. In the post-liberalization phase, the volume of foreign trade has increased, but, at the same time, the share of imports were always higher than the exports (see Table 2.5). This has contributed to the unfavourable balance of trade, as imports increased at 17.81 per cent per annum, while exports rose 16.6 per cent per annum during the period 1991–92 to 2000–01. As a result, there has been an almost six-fold increase in the balance of trade deficit during this period.64

Table 2.5 Performance of India’s Foreign Trade Sector: Trade Balance in the Post-reform Period (US $ million)

Source: Rudder Datt ‘Economic Reforms in India: An Appraisal’, in P.P. Arya and B.B. Tandon (eds), Economic Reforms in India: From First Generation and Beyond, New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 2003, p. 69.

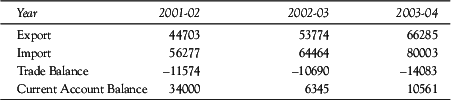

The situation has improved considerably since 2000 and India achieved a current account surplus in the years following 2001–02 (see Table 2.6). In fact, the rising surplus in the current account has been a distinguished feature of India’s balance of payments in the current decade.65

Table 2.6 India’s Balance of Payments Summary (2001–04) (in US $million)

Source: Economic Survey 2005–06.

A surplus current account indicates positive capital inflow and accumulation of comfortable foreign reserves. Thus, the year 2003–04 witnessed an accumulation of reserves of $13.74 billion.66

The initiatives taken to boast trade and attract investment had a major impact on the shaping of India’s foreign policy. Economic relations are becoming very crucial components of diplomacy. Major initiatives have been taken to strengthen India’s economic position in the increasingly interdependent globalized economy. These attempts can be analysed at the bilateral, regional and multilateral levels. Economic diplomacy is being pursued at different levels to achieve the objectives of projecting India as a major economic power; promoting multilateral trade and economic negotiations; forging regional and bilateral trade agreements like free trade agreements; forging attracting greater foreign investment; facilitating exports and expanding Indian businesses abroad.

At the same time, the instruments of foreign economic diplomacy have also been modified. This implies the setting up of new specialized institutional bodies to facilitate smooth economic negotiations with other countries and international bodies like the WTO, on the one hand, and enhancing the role of the non-state actors like the Indian diaspora and economic pressure groups like chambers of commerce in determining the course of economic diplomacy with other countries, on the other.

Major Initiatives at Bilateral/Regional Level67

Bilateral economic relations play a crucial role in bilateral relations between two countries in this age of globalization. This holds true for the emerging patterns of bilateral relations in the rest of the world as well. India has entered into free trade agreements and preferential trade agreements with countries like Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. Trade horizons are expanding for India with the emergence of China, Japan and Korea as important trading partners. Country-wise, Mauritius accounts for maximum FDI inflow to India (34.49 per cent), followed by USA (17.08 per cent) and Japan (7.33 per cent).68

The USA is India’s largest trading partner (country-wise) and accounts for 19.8 per cent of India’s exports and around 6.55 per cent of its imports. However, it is also noteworthy that India accounts for only about one per cent of USA’s total imports and exports.69 China also deserves mention in this regard as India’s third largest trading partner after the USA and the UAE. China (and Hong Kong) accounts for 8.4 per cent of India’s trade. Sino-Indian bilateral economic relations have taken a great leap between 2000–01 and 2004–05, with China’s share in India’s trade rising from 1.9 per cent to 4.7 per cent for exports and from 3.0 per cent to 6.2 per cent for imports.70

The recent developments in the India–Myanmar relation signalled a change in the orientation of the Indian foreign economic policy. Under ideological compulsions, no substantial progress in the Indo-Myanmar trade ties could be made since the installation of military junta rule in Myanmar under National Peace and Democratic Council. However, perceptions began to change after 2001. Since then, Myanmar has emerged as a strategically crucial economic partner for India. India is keen to import natural gas from Myanmar through Bangladesh, and also use Myanmar as a strategic corridor to the ASEAN region. At the same time, India has also offered to help Myanmar build constitutional institutions and democratic polity.

The progress in the Indo-Thailand relations are also indicative of the changing approach of the foreign economic initiatives towards facilitating bilateral cooperation. Though the India–Thailand Free Trade Agreement came into effect from 1 September 2004, an ‘early harvest scheme’ has been set up to provide fast-track elimination of tariffs on common items of export interest between the two countries. Similarly, the Indo-Singapore ‘comprehensive economic cooperation agreement’ has been a new initiative for closer economic cooperation.

Finally, one of the most important testimonies of the growing importance of economy in shaping bilateral relations is the recent trend in Indo-Pakistan relations. Though the relations between the two countries is dominated by factors like the Kashmir issue, cross-border terrorism and unsettled territorial disputes, economic diplomacy has gained prominence in easing tension in mutual interest. Attempts are being made to promote bilateral trade between the two countries through early activation of India–Pakistan joint commission and hold early meetings of the joint business council (JBC).

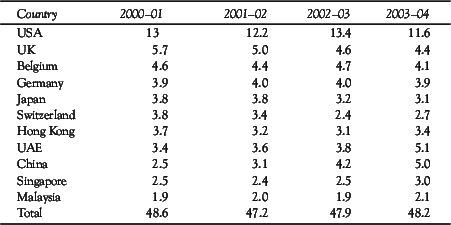

Table 2.7 provides a glimpse of India’s important trading partners between 2000 and 2004:

Table 2.7 India’s Major Trading Partners, 2000–2004 (Percentage share in total trade)

Source: Economic Survey, 2004–05.

Recent Trends in Regional Foreign Economic Policy Initiatives

An important role has been accorded to regional level cooperation and agreements in India’s foreign policy, over the recent years, and to a large part this can be explained by the economic factors. In the post-Cold War era, economic cooperation at the regional level has gained momentum. The success of ASEAN, European Union and NAFTA has inspired the formation and/or strengthening of other regional organizations like MERCOSUR in South America, ECOWAS in West Africa or BIMSTEC in South Asia, of which India is a founding member.

Regional level cooperations try to synergise the resources of the region for collective development. India too has taken the initiative to realize the objective of collective development of the South Asian region. In this regard, India has given priority to the successful activation of SAARC along the lines of ASEAN. India is also in favour of a South Asian free trade region. Shyam Saran, the foreign secretary of India, made this point clear in a speech delivered at the India International Centre (IIC) on 14 February 2005:

The challenge for our diplomacy lies in convincing our neighbours that India is an opportunity not a threat, that far from being besieged by India, they have a vast, productive hinterland that would give their economies far greater opportunities for growth than if they were to rely on their domestic markets alone. It is true that as the largest country in the region and its strongest economy, India has a greater responsibility to encourage the SAARC process. In the free markets that India has already established with Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan, it has already accepted the principle of non-reciprocity. We are prepared to do more to throw open our markets to all our neighbours. We are prepared to invest our capital in rebuilding and upgrading cross-border infrastructure with each one of them. In a word, we are prepared to make our neighbours full stake-holders in India’s economic destiny and, through such cooperation, in creating a truly vibrant and globally competitive South Asian Economic Community.

Another important feature of India’s foreign economic diplomacy at the regional level is its ‘look East policy’. Started by the Narasimha Rao government in the early 1990s and further promoted by the subsequent governments, it aims to explore the economic interests and greater cooperation in the Southeast Asian region. It was the result of this initiative that India became a summit-level partner of SAARC in 2002 and signed a landmark pact on ‘Peace, progress and shared prosperity’ in November 2004 during the third ASEAN–India summit held at Laos.71 In 2003–04, India’s export to the ASEAN region showed a growth of 26.1 per cent. Imports from that region also grew by 44.3 per cent. In fact, ASEAN + 3 (China, Japan and South Korea) has emerged as India’s dominant trading partners, accounting for 19.9 per cent of its total merchandise trade in 2003–04.72

Another region of increasing concern for India is the European Union (EU), with the collective economic strength of about 25 countries. The EU is India’s largest regional trading partner accounting for 21 per cent of India’s global trade. Yet, India’s share in EU’s global imports is around one per cent and India ranks 20th among EU’s trading partners.73 The EU has also sought a strategic partner- ship with India. A meeting held in New Delhi in February 2005, identified specific points in the joint action plan for such a strategic partnership.

The approach of India’s foreign economic policy is to diversify the scope of economic relations with countries and regions hitherto unexplored. For this purpose, the country has expanded trade relations with Africa and Latin American regions as well. These areas did not figure prominently in India’s external economic relations priorities in the pre-liberalization period. Even during 2002–03, sub-Saharan Africa (constituting of more than 50 countries) accounted for merely 4.19 per cent of India’s total trade.74 India’s trade with Africa is largely confined to 10 important countries.75 Therefore, in order to boost economic relations with Africa, the ‘Focus: Africa’ programme was launched in March 2002. It includes special emphasis on enhancing economic relations with select countries (presently 24). The Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) and the Special Commonwealth Assistance for Africa Plan (SCAAP) also deserves mention in this regard. These two programmes cover 156 developing countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Gulf and the island countries of the Pacific and Caribbean regions. They seek to provide opportunities for sharing with these countries Indian know-how and technological expertise on various aspects of development.

India has been focussing on energy security concerns that have shaped its foreign policy approach in dealing with Iran, the Central Asian Republics, Myanmar, Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh at different levels. At present, India imports 70 per cent of its oil requirements. With volatile oil prices and depleting global hydrocarbon reserves, India has adopted the policy to diversify the sources of energy. In this regard, it plans to expand exploration by acquiring oil and gas fields abroad,76 build a network of pipelines for gas transportation and to let oil interests influence traditional diplomatic ties. This has also compelled India to explore possibilities of cooperation with Pakistan and Bangladesh for laying gas pipelines to transport natural gas from Iran and Myanmar respectively.

India’s Foreign Economic Policy Approach at the WTO

Since its inception in 1995, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has emerged as the most important multilateral institutional arrangement for facilitating international trade. Though its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade (GATT) also played an important role in promoting free trade in the world, the WTO has emerged as a more effective forum due to its rule-bound institutional character and nearly universal membership. India has emerged as an important force to promote the interests of the developing countries at the WTO.

Though India was one of the founding members of GATT, it never played any important role in shaping the pattern of global trade due to the monopoly of the powerful Western countries. Even during the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations that finally led to the formation of the WTO, the voice of the developing countries was largely ignored. As India’s former foreign secretary J. N. Dixit, who was involved with the process of negotiations pointed out,

One has to acknowledge that though we participated in the negotiations actively and effectively and though we ultimately became a part of the final agreements signed at Marakkesh, we were not successful in fully safeguarding all our interests. Issues relating to intellectual property rights and export of goods and services were not resolved to our satisfaction and continue to pose problems for us even now.77

This led to a general apprehension among the developing countries including India regarding the utility of the WTO in promoting their interests. However, in the recent past, the focus of India’s foreign economic policy has been to utilize the WTO forum to promote its economic interests by tapping the greater market access opportunities provided by WTO.

As a developing country, India’s core concern is to expand its market for tropical agricultural products in the developed countries. However, agriculture has emerged as a highly controversial issue for negotiations under WTO. It is because of the alleged excessive agricultural subsidies provided by the developed countries (especially the export subsidy of European Union, and other forms of assistance provided by the USA and Japan) to their farmers, that artificially depress their prices in the global market. Moreover, it is alleged that the developed countries flood the markets of developing countries with cheap agricultural products by using the market access conditions under the WTO. To promote the concerns of the developing countries, India took the initiative in forming the G-20 during the Cancun ministerial conference of WTO held in September 2003. G-20 is a group of developing countries including China, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia that seeks to remove distortions in global trade that hinder the prospects of the developing countries. A crucial component of its agenda is fair trade in agriculture.

Other major areas of concern for India are the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), issue of inclusion of labour laws and environment in trade negotiations, issue of non-tariff barriers, antidumping rules, patents, trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPS), implementation issues, special and differential treatment, market access for non-agricultural products among others.

Finally, in order to promote the interest of the Indian economy in the external sphere, it became crucial to upgrade the diplomatic machinery to meet the emerging challenges in the globalized economy. In this regard, the Prime Minister’s initiative to establish the trade and economic relations committee to serve as a new institutional mechanism for evolving policies on economic relations with other countries is noteworthy. The committee comprising, among others, the Union cabinet ministers of key economic ministries and the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission as its members is headed by the Prime Minister. The committee’s main task is to coordinate the preparatory work for the strategy on economic relations with the country’s major economic partners, neighbours and regional economic groupings.

All these developments are indicative of the growing realization that economic aspects are acquiring prominence in India’s foreign policy in the post-liberalization era. Clearly, the priority concerns for the day are to maximize the opportunities provided by globalization at the regional and global levels.

Dr Manmohan Singh, the Prime Minister of India, emphasized this point in a speech delivered at the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) partnership summit on 12 January 2005:

…there is today a wide-ranging consensus on the necessity for India to be actively en-gaged with the world economy. Our government has already taken several steps towards this end. I have repeatedly reaffirmed our commitment to the successful functioning of the multilateral trading system and to broadening the agenda of the World Trade Organisation with an increasingly liberal flow of goods, services and labour. We are committed to lowering our tariffs at least to ASEAN levels. This is a policy priority for us….I have stated my commitment to the idea of creating an Asian Economic Community, an arc of prosperity across Asia, in which there are no barriers to trade and investment flows and to the movement of people.

At present, India is the fourth largest economy in the world with the second largest population. This provides ample opportunities and challenges for the rapid development of its potentials. The free trade opportunities provide India the opportunity to utilize its massive pool of skilled manpower and resources to the maximum. The challenge for India’s foreign economic policy lies in optimally utilizing its resources, capabilities and technical advances to create development prospects for the country and the South Asian region.

India faces a tough challenge in creating a peaceful environment of trust in South Asia. The apparent failure of SAARC and the proposed South Asian free trade agreement (SAFTA) is a matter of concern. India has, however, tried to bypass these hindrances by conceptualizing alternative regional arrangements like Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). Its recent foreign economic policy is also oriented towards exploring greater market access in the ASEAN region, Africa and Latin America. Forging partnership for energy security is another major challenge for India. Also crucial is to safeguard the national interests at the WTO negotiations.

The global economic environment has changed drastically since Independence. So have India’s foreign economic policy objectives. The objectives of the economy have undergone a sea change. Therefore, the country’s foreign economic policy too has evolved from a policy framework designed to promote protectionism and a planned economy into one that adapts to the requirements of a rapidly changing market economy. The level to which India can explore the growth potential provided by the liberalized global economy depends to a large extent on the manner in which it conducts its foreign economic policy in the years ahead.