Words change minds: the language of influence

Our language influences our perceptions.

Peter Senge, Leadership in living organisations, p. 75.

Outline

This chapter will share the essential language rules of influence to help you develop persuasive and compelling messages.

The building blocks of language

Learning is for babies. We are born with the ability to hear and to make every sound in every language in the world (which is around 6800 languages). Every language is complex and includes subtle distinctions which even native speakers may not be aware of, yet by the age of five or six years children across the world become fluent in their native tongue.

In terms of neuroscience, we are born with the mental scaffolding already in place to learn language. Language is made up of sounds (words) that prompt our brain to convert the word into a meaningful representation.

The power of language to direct attention

Language can unconsciously affect the decisions we make in everyday life. The social psychologist, John Bargh, from Yale University, has spent years researching the unconscious causes of our attitudes and motivations to find out how much of our social behaviour is affected by subliminal stimuli such as the words we see in advertising, or words we pick up in conversations on how this impacts on our decisions. Scientists call this ‘priming’.

Case study

In one experiment, some subjects were asked to read words which could be unconsciously related to the elderly, for example, bingo. When these subjects left the laboratory, they walked more slowly compared to those who had not read the words. In another experiment, those who were given words related to achievement performed better in a demanding word search than those who had not. It’s not only language that primes our unconscious responses; when the scientists put a backpack in the room it prompted more cooperative behaviour from the group whereas a briefcase prompted more competitive behaviour.

There’s a significant body of research into the effects of priming on consumers by the use of both symbols and language and much of the research challenges the idea that we are consciously making many of our choices. Bargh argues that much of the mental processing that drives our decision-making takes place outside of our conscious awareness and that priming means many of our choices are made as if we are on auto-pilot. Bargh says of free will:

Clearly it is motivating for each of us to believe we are better than average, that bad things happen to other people, not ourselves, and that we have free-agentic control over our own judgments and behavior—just as it is comforting to believe in a benevolent God and justice for all in an afterlife. But the benefits of believing in free will are irrelevant to the actual existence of free will. A positive illusion, no matter how functional and comforting, is still an illusion.

Sources: Bargh, J A et al. (1996) The automaticity of social behavior: direct effects of trait concept and stereotype activation on action.

Bargh, J A et al. (2001) The automated will: nonconscious activation and pursuit of behavioral goals.

How neuroscience explains why the message you send is not the message received

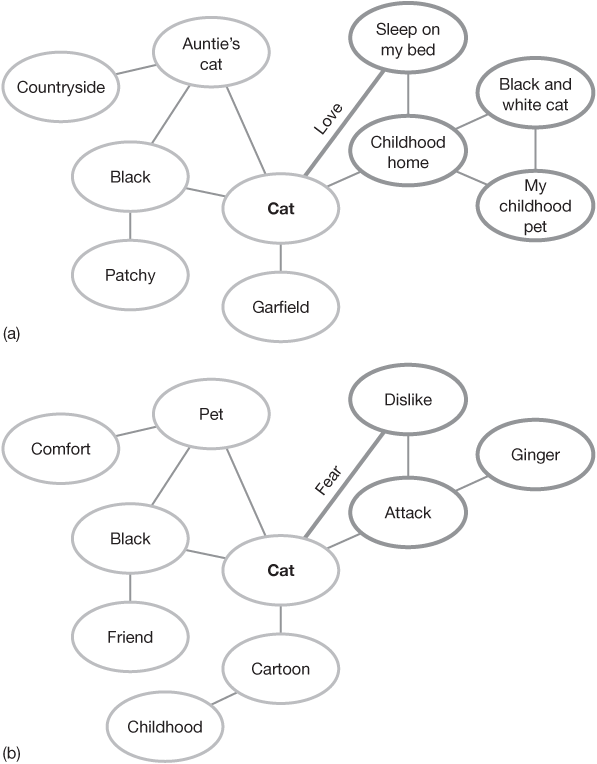

If our brains are organised to understand and communicate with others from the day we are born, why do we sometimes get it so wrong? How is it that, even when we speak the same language, we can feel as if we don’t? How does language get to be so tricky? And how can we make sure we use it as a powerful tool for influence? Let’s start by looking at how our brain processes a single ‘packet’ of language such as the simple noun ‘cat’. Put this book down for a moment. Close your eyes and think of a cat. What image came into your mind? How long did it take you? Did you notice the sequence your brain went through to make your choice? Probably not; the neurological activity that takes place to process language happens so quickly and involves a process that goes something like this – first, the brain has to recognise a group of letters as a ‘word’ that belongs to the language rules coded into your mind. If you were asked to think of a ‘dvpt’, your brain instinctively knows not to bother starting a search because the sequence of letters breaks the unconscious rules of English. But once your brain recognises that a group of letters (or a spoken word) is a ‘word’ it performs what linguists call a ‘trans derivational search’ and scans across billions of smaller bits of information stored in different areas of the brain.

However, given that we are likely to have many experiences of cats, how do we go about selecting one particular cat above all others? Everything we experience is coded into the brain with an ‘affective tag’ – whether it is associated with pain or pleasure. So the first rule of recall is to search for the strongest emotional associations with a word which could be negative or positive (a much loved cat, or a cat that terrified us). Emotional memories are stored deep in the limbic system so this is the first place the brain searches, triggering associated sensory memories which may in turn generate images in the visual cortex, tactile associations in the sensory cortex and auditory associations in the auditory cortex.

When the memory of your ‘cat’ pops into your mind, it does so as an instantaneous, coherent single memory; but your brain has just performed the hugely complex task of reassembling an experience stored in parcellated bits of information across the various brain cortices at warp speed. If you ask ten people in a room to think of a cat, no two cats will be the same. Cat owners or those who strongly dislike cats come up with a memory first because their brains hold strong emotional associations with the word. But those who have no strong emotional associations take the longest time to choose, for them all cats are pretty much the same: Garfield, the neighbour’s cat, the cat next door. Yet everyone selects on the basis of their personal experience and everyone’s cat will pop into their mind with their own visual, auditory, kinaesthetic and emotional associations.

The resulting emotional tag increases the likelihood of the recall of the event/object. This is all about the emotional flavour of the memory and the associations that are triggered. Figure 4.1 gives examples of positive and negative emotional tags associated with the word ‘cat’.

If the word ‘cat’ has so many different associations, think about the variety of personal associations with more loaded words, such as God, family, school, friends, work, money, sex and love. These are not only likely to differ between individuals but also within each person. How has the meaning of these words above changed from when you were six years old compared to now?

Exercise

Take one of the words above or any word you choose. Sit quietly for a moment and close your eyes. Say the word to yourself and, as you do so, pay close attention to any images, feelings, other thoughts and words and memories that come into your mind. Pause.

Resist the temptation to carry on thinking about what you’ve experienced in the mind and keep watching what arises. Repeat the word again and see what arises.

Try it with a friend and see what you notice.

We think of language as universal and shared and of words as ‘fixed’ descriptors of a simple truth; what could be more straightforward than a simple noun such as ‘cat’? How can we each have such different emotional responses, internal images and meanings? Words are powerful containers of personal meaning and sometimes the message you think you’re sending is not necessarily the message received.

FIGURE 4.1 (a) While your brain may generate a number of memories of cats, the one that will come to the forefront is the one with the strongest emotional tag. (b) If you were attacked by a cat as a child, the emotional tag for this semantic node will be strong but also negative so you will very quickly remember that cat and possibly experience sensations of fear in the body.

1st rule of language as a tool of influence:

Remember that my cat is not your cat – once we understand more about how our minds process language we can use language that directs the mind of the other person to where we actually want it to go.

Let people make connections

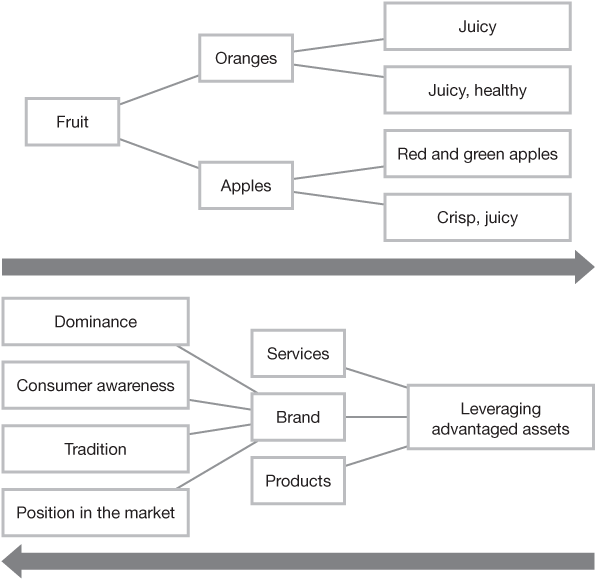

So once we’ve learnt simple words as children – a single word for a single object – we take the next step on the linguistic ladder and begin to group words into what’s known as classifications. We now start to move into more abstract use of language. For instance, think of the word ‘fruit’; there’s no such thing as fruit there are only individual items of fruit – a banana, an apple, an orange – that our mind groups together to understand the concept fruit.

We’re not conscious of what our brain is doing to process the word fruit because it’s working at a speed which (even our own brain) finds hard to contemplate – 20 billion calculations per second. And then our brain does something even more elegant; it understands fruit by connecting the word inside a web of semantic meaning (see Fig. 4.2): ideas of eating, nourishment, shopping or gathering, peeling, colour, texture, smell, memories. Semantic meaning is different if you live in Asia or Europe because you will group different individual fruits together, but each person will have different types of fruit. A child might ‘hate’ the idea of eating ‘fruit’ while someone who is health conscious might ‘love’ the idea. So while the word will have its own emotional ‘tag’ for each person, the brain is working at a more complex level to understand what the word means. But it’s still relatively easy for our brain to unpack a classification such as fruit because what’s inside the classification are individual sensory-specific items that we have experience of: bananas, apples, oranges.

FIGURE 4.2 We understand language through a rich network of unconscious semantic meaning.

But when we start to use abstract language (which for anyone who works in business is words like strategic advantage), the brain goes off to search for feelings, colour, texture, images and comes back empty-handed. So by using these sorts of abstract words you are asking the brain to climb right to the top of the linguistic ladder and then to engage in the most brain hungry processing possible.

Jargon is hard work for the brain

Jargon is one of the biggest offenders when it comes to influential language because it’s abstract, conceptual language that is harder for the brain to understand and create internal associations with. We know that emotions are the sparks that motivate us to do things (or avoid things) and that energise us when we’re listening to other people. When a speaker uses too much jargon, or doesn’t give the audience quick ways to understand and interpret it, it simply switches off the brains of the audience. If a CEO said in a presentation that the business plans to leverage its advantaged assets your brain tries to unpack what individual items might belong inside the classification – it could be your products, or services, or new customers or a whole other range of things, but whatever you come up with you will be making a guess. So when you ask your audience to guess at the meaning of your communication you are failing to influence.

When we use simple sensory-specific language, the network easily spreads outwards. This doesn’t take a lot of effort for the brain because much of it is drawn up automatically and we add and embellish ourselves. All the content is personally meaningful (which the brain loves). In contrast, when we work with high-level abstract concepts and jargon, the process starts several layers out and we ask the brain to work back to find the specifics of the classification. These processes are illustrated in Figure 4.3. This process of working backwards takes a lot of effort for the brain. It does not flow easily, is not personally relevant and is difficult to understand. A spreading network is less effort for the brain than a contracting network. You can think about these two brain processes as water flowing effortlessly outwards, or like trying to push water uphill.

2nd rule of language as a tool of influence:

It’s easier for networks in the brain to expand than to contract. The brain has a propensity for mental proliferation – semantic networks are the building blocks of this.

Jargon creates barriers

There are other problems with jargon that make it toxic when you want to communicate your message because jargon communicates whether you’re an insider or an outsider in a group. Have you ever started a new job and spent the first month trying to get to grips with the acronyms, sayings, terminology and jargon of the organisation? When I joined a large global bank, I remember the anxiety I felt when confronted with a new language. A year later I could use many new words in conversation but, as a communicator, when I sat down and tried to decode them for employees to make the communication more concrete and simple I struggled because my mind couldn’t create an internal representation of words like risk weighted assets, capital adequacy ratio, EPS, ROCE; they floated around in my mind – vague and colourless. Of course jargon plays an important role (as a short cut for a wealth of complex ideas and concepts) for senior bankers, financial analysts and specialists, but the problem comes when it’s over-used and dominates the conversation in the business. Because jargon communicates a subtle and implicit question (are you one of us?), it creates insiders and outsiders. Business jargon is used by leaders and middle managers (and rarely by people on the shopfloor) so it reinforces an ‘us and them’ mentality and, if we’re not careful, we can create a linguistic class system that keeps people in different tribes.

Because CEOs spend years developing their understanding of the business and technical terminology they feel very connected to it, but the average employee has not developed their own rich associations; they are just learning by rote.

3rd rule of language as a tool of influence:

Avoid using jargon and abstract language if you want to connect with your audience and include everyone in the conversation.

If you are a specialist, such as a CEO, a scientist or a technology wizard, you will stand out from the crowd, educate and inspire your audience when you are able to share your specialist knowledge in a way that is easy to understand and to remember. There’s nothing quite as inspiring as finding out about new ideas in fields that are unfamiliar to you, and those who are able to bridge the communication gap between their speciality and the rest of us are truly great communicators. Chances are they will have found a way to turn the techno-babble into pictures, emotions and colour by using stories, metaphors, similes and images to help your brain make a connection between something you already know and something that is new. That’s where metaphors and storytelling (Chapter 5) can help you build a linguistic bridge with your audience.

Tips for keeping your message simple:

- Be aware that jargon has to be learnt and then reverse-coded/decoded every time it’s used – this is effortful for the brain.

- Converting complex information into easily digestible and tasty nuggets flavoured with emotion and colour will make it memorable.

What we need to stop saying

Negative language creates negative feelings

Using negative language directs someone’s attention away from what we want. Imagine you’re in an exercise class working really hard, with perspiration dripping down your face, your t-shirt is stuck to your back, you’re gasping for breath and on the edge of your physical limit when the personal trainer shouts in a loud voice, ‘Don’t stop!’ Your brain finds mental associations with the word ‘stop’, such as slowing down, breathing normally, relaxing your muscles and then has to reverse these images to understand the instruction is actually to ‘keep going’. If you say to a child ‘don’t fall’ or ‘don’t touch’ you’re directing their attention to create an internal mental picture of falling or touching something in order for them to understand your instruction. Yet we use this language all the time.

Case study

When I worked in communications in a large global bank we were asked to put together a campaign that would help to change the behaviour of employees and make them more security conscious when handling customer data. The campaign was a response to the bank being fined £5m by the FSA (Financial Services Authority) following a string of IT security failures, and the senior IT director suggested we communicate the ‘10 things not to do’. But by understanding that the brain processes negative instructions by creating mental images associated with the things we don’t want, we developed a campaign using positive messages; instead of saying ‘Don’t leave your laptop unlocked’ we used a series of questions, such as ‘Safe to leave?’, ‘Safe to send?’, to prompt people to think consciously about their actions and to allow them to make an informed decision. Messages that string a list of ‘do not’ instructions together also create internal triggers (internal images, memories and feelings) of being a child at school or at home when we were ‘in trouble’ so they can be counter-productive when you want to build understanding and rapport with your audience.

Our brains are also not designed to remember a list of 10 things. There’s a rule of memory which says that, on average, we can remember ‘seven, plus or minus two’; what this means is that most people can remember seven things, some people can only remember five, and others can remember up to nine. So as a communicator it’s wise to limit your list to seven (and shorten it if at all possible). If you think about how the brain recalls telephone numbers (normally 11 digits), we group them into smaller chunks of three or four digits which are much easier to remember. If you really want people to remember some important points or instructions, avoid creating automatic lists of ‘the top 10’.

We launched our campaign at the bank with seven important messages for employees (we had to wean the IT Director off the 10 commandments syndrome), but it would have been more memorable to stick to five items. Once you understand these simple rules of language and how your brain processes your messages you can make sure your messages stick.

Tips for influential language:

- Tell people what you want them to do (use positive language).

- Adding ‘don’t’ to an instruction forces the brain to do an extra level of cognitive processing.

- If you want people to recall information keep your lists to between five and seven main points.

Turning verbs into nouns (nominalisation)

Proper nouns describe things in our world – a tree, a river, a boat – but there’s another type of noun we often use called a nominalisation; the words ‘relationship’ and ‘communication’ are all instances of nominalisations. Let’s unpack the word relationship; there is no such thing as a relationship – a relationship exists only in language and not in our lived experience. In our real life, relationships are the sum total of a whole lot of things we do when we are relating to other people; talking, sharing, listening, etc. But when we turn all of these activities (verbs) into a single noun, we end up fixing it in our mind.

For example, imagine that your best friend comes up and says to you: ‘My relationship has failed.’ How do you immediately feel? What’s the first image that comes into your mind? It feels a bit like a concrete statement of fact (concrete is a good way to remember how nominalisations work in the mind because they ‘fix’ something). But part of the problem with the statement is the word itself (relationship) because our thinking is directed away from all of the different parts of relating to others. As soon as we turn (dead) language back into (living) experience, we open up new possibilities and new ways of thinking. We can do this quite easily by putting the suffix – ing – back onto many words.

Let’s take a look at how this works. You could ask your friend: ‘What specifically is it that’s not working in the way you are relating to X?’ Their attention now has to turn inside so they can begin to search for things to help them answer your question; what is it that is specifically happening? Where is it happening? When is it happening? Who is doing the action? They have to move back into the world of lived experiences.

Moreover, by including in the question the words ‘you are relating’, we introduce the idea of agency (a term used to describe the capacity we have to act in the world), so the person begins to focus on what it is they may like to do about the situation. It invites action or consideration of action. This also avoids making the assumption that the ‘other person’ is to blame for what’s not working and draws the person’s attention to their own sense of agency so they can consider new possibilities, options, choices and actions.

Another example of a nominalisation is the word confidence. This does not exist; you cannot go into a shop and buy it (it’s not a book). Confidence is made up of many different skills, behaviours and beliefs. The skills involved in confidenting (grammatically incorrect but a more useful way to think about the activity) can be practised so that we become more confident and continue to become more confident the more we practise. Nominalising verbs can be a powerful linguistic trap – because it can stop us from seeing what’s really happening.

Remember that language is all about directing our attention and nominalisations can stop our attention from going to the places we need to go. How we think about something makes all the difference in the world; the ability to think clearly, question wisely and use our mind to help us overcome problems and find new solutions is the most powerful gift of influential communication. If you are a coach, parent, friend or colleague, use this very simple language rule to help others get ‘unstuck’. And this rule applies to your own internal self-talk so try out the exercise below and notice the difference denominalising your life can make.

Exercise

Turn the following words into verbs:

Credibility

Persuasion

Communication

Influence

4th rule of language as a tool of influence:

Turn dead language back to living experiences. Activate your brain by activating your language – this encourages more ‘movement’ in the mind and in finding more creative solutions.

Shifty language

Nominalisations are sometimes used by businesses and politicians to shift responsibility for a particular decision or action – for example, if a CEO presents a decision as being made by the leadership of the business (rather than himself or the leaders in the executive team). There’s no such thing as leadership, only people who lead and who are responsible for taking decisions. The word management is also often used in this context. These words are often used when leaders want to distance themselves from ‘blame’ or responsibility, but the danger for leaders who use these when delivering difficult messages is that they distance themselves from employees and lose trust and credibility.

Another example of shifty language is the phrase ‘It has been decided’ which only begs the question ‘By whom?’ One of the most infamous examples of this use of language was when Donald Rumsfeld, the US Secretary of State in George Bush’s administration, said, when responding to journalists about the Haditha massacre (where 24 unarmed Iraqi men, women and children were killed by a group of United States Marines), that: ‘Things that shouldn’t happen do happen in war.’ Or, in street slang, ‘Shit happens. Get over it.’

The author Henry Hitchings decribed this phenomenon very clearly:

Nominalizations give priority to actions rather than to the people responsible for them. Sometimes this is apt, perhaps because we don’t know who is responsible or because responsibility isn’t relevant. But often they conceal power relationships and reduce our sense of what’s truly involved in a transaction. As such, they are an instrument of manipulation, in politics and in business. They emphasize products and results, rather than the processes by which products and results are achieved.

(Hitchings, H, 2013, The dark side of verbs-as-nouns)

5th rule of language as a tool of influence:

When we want to influence others to support us, we need to use open and honest communication and acknowledge who is taking decisions.

What we need to start saying

Metaphors

Metaphorical language turns complex information into a brain-friendly format so we can map over knowledge from something we have prior experience of to something that is new or different. When we hear metaphorical stories, our brain searches for similar experiences and we activate a part called the insula, which helps us relate emotionally to the story. An example of using metaphor to create a bridge between shared experience and something new and unknown is when we use the metaphor of the brain as a computer: this triggers many other associations and images such as coding, being hardwired, connected, the brain as a processor of information, or holding information in bits. Because we already hold sensory-specific images in our mind about computers (boxes, wires, information flows, screens, electricity, programmes), it’s easy for our mind to use these hooks to create internal representations of how the brain works.

But while metaphors are often useful shortcuts, the brain as computer metaphor also constricts and limits our understanding – perhaps the brain is not so much a discrete piece of wetware (another metaphor) but a more complex, connected, organic and embedded process? By mapping an organic process to a physical, electrical, man-made object, we may also constrain understanding, so choose your metaphors wisely; think about the internal representations and feelings you want to evoke in your audience when you use a particular metaphor.

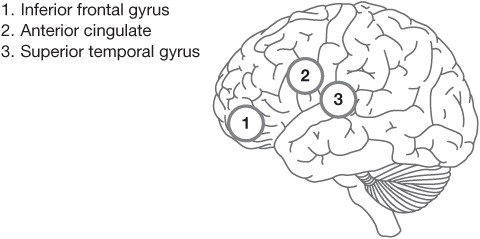

Understanding metaphor takes quite a lot of brain effort and requires that we use both left and right regions of the inferior frontal gyrus (to understand the concept), the superior temporal gyrus on the right side (to understand the context) and, finally, the anterior cingulate that helps us to focus long enough to work through the metaphor (see Fig. 4.4). But while it takes effort for the brain, it’s also very satisfying because it gives us a broad and rich semantic network that allows us to cross-reference and build a rich image and deeper understanding. Once you have a metaphor that works for you it helps to build layer upon layer of meaning. If we hold a metaphor of the brain like a computer in mind then each time we learn about a new part of the brain, or another way that it processes, we continue to build up metaphoric connections which help us understand and remember.

Metaphors can also help get our message across with the least possible resistance in the minds of the audience. People don’t question metaphors in the way that they question data, facts, statistics and other information. When we’re presented with facts our minds are more likely to question and ask ‘Is it credible?’, ‘What’s the evidence?’, ‘Who said so?’ etc. We use different parts of our brain when we are faced with facts (the more discerning areas that look for validation) than metaphors (the more visual and emotional parts of the brain).

Think about what comes to mind when faced with the metaphor of the ‘American Dream’, as opposed to a US politician delivering the dry details of a specific policy. If you’ve seen President Obama speaking at one of the big US political conventions or at the Presidential Inauguration, you will recall that the language used is full of metaphor, images, analogies, stories and never about dry specific policy details. Political language is the language of emotional persuasion; you might even think about it as the language of trance as the audience is carried along on an unquestioning emotional journey (because our brain doesn’t question emotions, only ‘facts’). It’s not surprising that people in groups who listen to skilled communicators using metaphorical language end up being almost of ‘the same mind’. Politicians and businesses are only too aware of the power of language to convince, persuade or dissuade consumers and voters.

FIGURE 4.4 The brain regions involved in processing metaphor.

The power of frames

Another influential language tool which is a close cousin to the metaphor is ‘framing’, a language tool used by influential communicators to sell and persuade. A few years ago I visited the Tate Modern art gallery on London’s South Bank with a friend and asked her what she liked about a particular painting we were both looking at. She said that she loved the frame and that whenever she looked at a painting it was the frame that she noticed first. She said that the right frame could make an ordinary picture great and the wrong frame make a great picture ordinary. I was completely taken by surprise. I realised that she noticed something that I paid little or no conscious attention to at all. There are also linguistic frames that operate in exactly this way; they are outside of our conscious awareness but they have a profound effect on the way we construct meaning and interpret language. While linguistic frames are everywhere, we rarely notice them because our attention is drawn (and held) inside the frame.

One example of a linguistic frame is that used by the Bush administration in 2003 to introduce a new piece of legislation it called ‘The Healthy Forest Restoration Act’. The Republican Party is very conscious in its use of language and has invested significant time and money in think tanks that come up with compelling linguistic frames to direct the public debate. The stated purpose of the new legislation was to reduce the risk of wild fires by thinning dense undergrowth in forested areas, but it did not come without controversy (hence the importance of the frame), and environmental groups argued that it was an environmental disaster and allowed the timber industry to make a windfall because it allowed them to cut down valuable timber previously protected by law.

By naming the legislation ‘The Healthy Forest Restoration Act’, the administration sought to create positive subliminal emotions in the minds of the voters. In the same way that the word fruit activates a rich semantic network of internal representations, The Healthy Forest Restoration Act activates unconscious positive feelings and associations in the minds of voters every time it is used in the press or TV. This frame is designed to create associations with wellness, vibrancy, energy, life ( healthy) and bringing something back to life, improving, regenerating ( restoration). By consciously using this linguistic frame, the administration sought to contain thinking (inside the frame) and close down debate. But environmental groups have become aware of the power of language in public debate and came up with their own frame to draw attention in a different direction entirely by calling the Act ‘The No Tree Left Behind Act.’ This frame creates very different internal associations: destruction, desecration and the end of the world.

The cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, has spent years studying the way political parties use linguistic frames to control and direct the public debate and believes that frames are so powerful that they ‘trump facts’. Lakoff says,‘Every word is defined with respect to frames. You’re framing all the time.’ Morality and emotion are already embedded in the way people think and the way people perceive certain words – and most of this processing happens unconsciously. (Explain yourself: George Lakoff, cognitive linguist, http://explainer.net/2011/01/george-lakoff/).

What’s your frame?

Another recent example of powerful framing was when a UK lobbying group that was fighting the introduction of plain packaging on cigarette packets on behalf of a group of tobacco companies put out a press release stating that the introduction of plain packaging would ‘create the perfect storm for black market expansion’. The mental associations in this frame are of disaster and criminality. The words ‘the perfect storm’ unconsciously trigger images and emotions from the Hollywood blockbuster The Perfect Storm; ordinary, likeable small-town fishermen being overwhelmed by a monstrous and unnatural ocean. The frame seeks to position the tobacco companies as protectors and concerned corporate citizens (why else spend money warning the public of the danger of plain packaging?). And the frame seeks to move attention (in the minds of readers) away from notions that plain, unbranded cigarette packets could potentially ‘save lives’, ‘prevent further deaths from smoking-related diseases‘ or even ‘reduce the profits of tobacco companies’.

Here are some other common linguistic frames used to shift opinion, focus attention and persuade people to a cause. Try them out for yourself and see what internal associations you come up with in your mind. Think about when you last saw these frames used in the press. Are you conscious of when frames are being used? By being more conscious of framing you can both question its veracity and also use framing in your own messages to direct attention and persuade people to your cause.

Tax planning as opposed to tax dodging

Companies use the term ‘planning’ which is a responsibility frame; when we think of the word planning we think of efficiency and responsibility. In contrast the protest group UK Uncut frames the issue in terms of ‘dodging’ – a moral frame because people who dodge are avoiding doing something that they are responsible for. Dodgers make other people carry their share of the work (tax) of the group and place unfair burdens on (poorer) citizens.

‘Big Tobacco’ or ‘Big Pharma’ as opposed to ‘the tobacco industry’ or ‘the pharmaceutical industry’

Big implies global, multinational, conglomerates that span country borders and are therefore not accountable at a single country level, as opposed to industry which is a frame of economic and social productivity within the borders of a single country.

Anti-ageing as opposed to, say, moisturiser

This is an emotionally-driven ‘away from’ frame that has a significant impact on consumer decision-making to buy products or services. Attention is drawn to associations with disease, the end of life, dying. While the word ‘anti’ operates in the same way as the word ‘don’t’ we first have to think about ageing and then ‘reverse’ it to understand what’s being said. If a product was sold by using positive language it would be called ‘youth’ or ‘young’ (some products are indeed called things like ‘youth serum’ but the bigger share of the market is framed in ‘away from’ language because fear is the most powerful motivating force there is).

The right to life as opposed to the right to choose

Both frames talk about ‘rights’ (inalienable, applied to everyone equally). For anti-abortionists the most basic human right is to life which this frame positions as a higher value than ‘choice’. In this frame, attention is directed to the existence of the foetus (and not the woman). A life is being denied by the woman who seeks to have an abortion. For pro-abortionists, the rights they are seeking to protect are those of the woman – the right to choose what happens to her own body. In this frame, attention is directed to the woman (and not the foetus). Both are moral frames. A secondary frame that is used in this debate is the use of the word ‘foetus’ as opposed to ‘unborn child’.

Frames are also values

All of the frames above are also deeply value-laden; they are not neutral and they attempt to influence our values by touching on powerful emotional triggers. Frames can be used as a negative or positive tool of influence (depending on your intention) so be aware of their power and use them wisely.

Many companies ‘brand’ change programmes to make them memorable. But beware of the power of the frame. If a company calls a change programme ‘Together for a Better Future’ and employees experience insecurity, job losses or changes to their pay and benefits, the name of the programme can become a lightning rod for dissent and anger. Think of the power of a political frame turned against the politician who uses it to influence voters as was the case when Prime Minister David Cameron said: ‘We’re all in this together’. Voters did not fail to notice the discrepancy between stories of bankers’ bonuses, company tax havens and company tax avoidance with the idea that austerity is a shared economic reality.

Source: Gary Barker Illustration

Choose your frame wisely or it may come back to haunt you.

Exercise

- Notice how frames are used in the press, in advertising, in politics and in public debate.

- Next time you go shopping notice the frames that convince you to buy.

- What frames are most commonly used in public debate and politics?

- What values are being expressed within the frame?

- What emotions does the frame evoke? Is it an away from or toward frame?

Presuppositions

A presupposition is ‘an implicit assumption about the world or background belief relating to an utterance whose truth is taken for granted’ (Wikipedia.org). When you use presuppositions you are making an assumption that something has already happened. An example of an effective presupposition was used by one of the judges on the UK TV show The Voice (where successful singing contestants get to choose the judge they want to be their coach) when one of the judges said to a contestant: ‘I look forward to working with you and to writing songs, recording, putting out records.’ The judge was using a presupposition as a way to make the contestant imagine these things happening in their mind. It’s a very seductive technique, and one which is used subliminally to influence choice and action.

You can use presuppositions by saying things like:

- ‘When we are all together this time next year, we will be able to look back on our successful project.’ (You are presupposing that you will in fact be together at the same time in a year and that the project will be successful.)

- ‘At our next coaching session we can review your progress.’ (You are presupposing the person will book another coaching session and will have made progress.)

- ‘I look forward to meeting up again, once you’ve had a chance to review the proposal.’ (You are presupposing the client wants to meet again and that they will have read the proposal and be prepared to review it.)

These presuppositions are influential because they create an imagined future in the mind and act as subliminal command. A presupposition can persuade someone to make a choice they may not have made otherwise; how would you respond if the coach (in the second example above) said at the end of your first session: ‘Think about whether you’d like to book another session and then give me a call.’ The presupposition is that you need to consider whether or not you want another session (so your attention is drawn to having to make a conscious choice between two different options). This is an example of a negative frame for selling. So be conscious of your own presuppositions. The imaginary coach in the example above may have strong values about ‘not being pushy’ but, without realising it, they may actually be dissuading potential clients from using their services.

Use presuppositions to positively influence others at home or at work, e.g. if a colleague is having a difficult time you might say: ‘Just imagine in a couple of weeks when this is all over and you’ve succeeded in achieving your goal.’ This will help them imagine how they will feel when the pressure is off and the goal has been achieved and will help to keep them motivated.

Exercise

- Practise using presuppositions in your work to help colleagues or your team achieve stretching goals.

- Next time a friend is in need of encouragement, consciously use a presupposition to support them.

- To improve your sales, use presuppositions in your website copy, promotional brochure or in meetings with clients to increase their motivation to buy your products.

Small words that have a big impact

- Try: Try is a linguistic get-out clause; what it really means is that we are unlikely to do something. It communicates ambivalence and uncertainty and is best avoided. Being influential and persuasive is about being honest and direct and building your credibility with others. If you’re not sure whether you can do something, frame it in a positive way, e.g. ‘Let me get back to you to let you know if that’s possible in the timeframe.’ This gives you time to work out whether it is possible and, if not, to prepare your next response.

- But: But tends to negate what comes before the word, e.g. ‘I really like your ideas but …’ The other person will focus on what you say after, and will interpret the first part of the sentence as little more than a way to ‘soften the blow’. The word ‘but’ communicates your discomfort in delivering a clear message and has the effect of making your message even more negative (because why else would you need to ‘soften it’).

- And: Replace the word ‘but’ with the word ‘and’ when you want to communicate a difficult message: ‘I really liked your ideas and I’d appreciate some additional information to help me decide.’ This will help the person to hear both messages as equally important rather than the word but which is a qualifier.

- Might, May: These words are called modal operators of possibility (modal because they create a certain mood in the mind of the listener and possibility because they allow for different possible outcomes), e.g. ‘You might like to...’, or ‘You may find this important’. You avoid presupposing something and ‘soften’ a suggestion. Used in the right context, they are powerful because they show respect for the other person’s choice and build empathy.

- Should, Must, Mustn’t: These words often evoke a negative response and are likely to make somebody think ‘Says who?’ or ‘Why should I?’ They assume that we know best, or that our opinion is the ‘right’ one. These are command words and to be avoided if you want to build understanding and positive influence.

Brain Rules:

- Notice how language directs attention.

- Use these language techniques to positively influence others.

- Words with strong emotional tags elicit the mental representation faster and stronger (e.g. the cat example).

- Our brain understands words in the context of a rich semantic network (e.g. fruit).

- Use frames to direct the listener’s route through their semantic network.

Top Tips:

- Use clear, plain language to communicate your message and avoid jargon.

- Use metaphors if you need to use abstract language to help people understand.

- Emotion – it’s your friend. It’s in the room. It’s everywhere. Acknowledge emotion and weave it into your message to persuade and convince.