Influence matters

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Outline

This chapter sets the scene: what influence is and why it’s so important; why neuroscience helps us understand how influence works; how to set your goal for what you want to achieve.

What is influence?

Being able to positively influence others is one of the most important skills for success in our personal and professional lives. But what do we mean by this word influence?

It’s a tricky word – both a noun and a verb – something we ‘have’ and something we ‘do’. Like a lot of words, it packs a big punch because it means so many different things to different people. If you do an internet search you will come up with Time magazine’s annual list of the top most influential people, which in 2013 includes Jennifer Lawrence (actor), Jay Z (musician, entrepreneur), Malala Yousazai (social activist), Elon Musk (inventor and entrepreneur) and Hilary Mantel (author). These people influence others through their art, their talent, their intellectual genius or their commitment to a cause – they paint a picture of another world, show us what we are capable of and nourish our creative spirit. But it’s not just about the talented, the well-connected or the well-educated. Think of people like Rosa Parks, Camila Batmanghelidjh (The Kids Company) and Paul and Rob Forkan (Gandys flip flops) – these are ordinary people who choose to make a difference in their own unique way. While we might look up to pioneers, visionaries and talented souls, we can each turn up the dial on our own personal influence whether we want to garner support for our cause, inspire others to help us, build our business or be a better leader, coach or friend.

Why is influence important in business?

While influence might take years to build, it can also be lost in a heartbeat. The Time magazine list in 2004 included names such as Lance Armstrong and Mel Gibson, in 2009 Tiger Woods and in 2011 Dominique Strauss-Khan – but all of these have now suffered a fall from grace. In the past ten years, many industries and institutions have suffered the same fate as, one by one, they have been found to be wanting: a financial system that has turned the global economic system on its head; UK politicians who now experience the lowest level of trust for years; a section of the press that invaded personal privacy for profit; and corporate giants who spend more on green-washing than on safety and economic fairness. In this world of ‘always-on’ social media, customers, consumers and voters not only switch allegiance but actively spread the word against those who are found wanting. All of these institutions have suffered huge reputational damage and will take years to recover the trust of consumers and voters. Influence is hard won and quickly lost …

The dial of influence

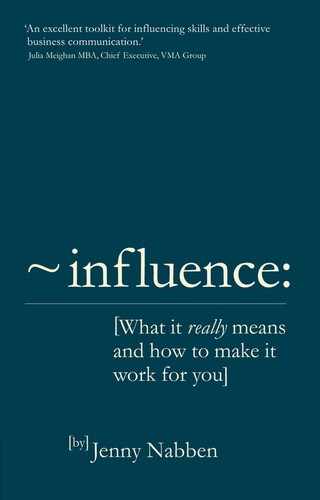

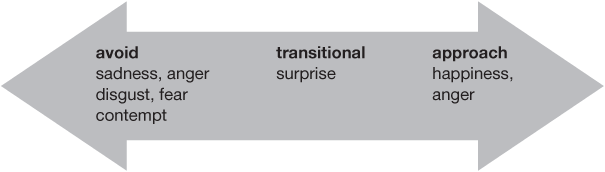

If building our confidence is about having a better sense of our self in the world, influence is about having a bigger effect on the world. The skills of influence are built on finding the balance between heart and head, between using our intellect and using our emotional intelligence, between knowing when to push through and knowing when to yield to others. While it’s not about using positional power to get what you want, it’s also not about withdrawing your power and being shy of standing firm when you need to. To influence others we need to stand up and be heard, but we also need to sit still and listen deeply to what others have to say. Influence is the sweet spot right in the middle of all these (see Fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Influence is the balance between left- and right-brain skills and behaviours.

What can neuroscience tell us about influence?

Every time you seek to persuade, convince or motivate another person you are looking to affect the way they think and feel about your product, your idea or your cause. You want them to say yes, or no, to remain loyal or jump ship, to speak up or speak out. And here’s where neuroscience can help – because it provides new insights into how our brain makes meaning of language; why emotions, not logic, drive many of our decisions; why stories trump facts when we want to sell our ideas; and why listening, not talking, can be the most effective influencing skill of all.

Neuroscience is the big kid on the block and punches above its weight as one of the most rapidly expanding fields of scientific research. The growth in this new field of science has been fuelled by the development of new technologies such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG) and chemical neuroimaging (positron emission tomography – PET) to measure changes in brain activity under different conditions. These new technologies allow scientists to map the hidden structures of the brain as well as to study what’s really happening across the brain network as groups of neurons fire and communicate. But neuroscience is not so much a discrete study of the grey matter inside our heads, as it is a rich field of knowledge that includes chemistry, computer science, linguistics, mathematics, philosophy, physics and psychology.

While brain science began with the study of a single discrete brain, it has now expanded to include new disciplines such as interpersonal neurobiology which studies how two brains in two bodies interact and affect each other at the level of their neurobiology. What this means is that our emotions, language and even our thoughts have the power to affect the brain states of others for better or worse. If we thought that our brain was a single, discrete and private entity, we now suspect it may be more like a single node in a vast complex network. Our brain state not only affects us but also impacts on others via subtle processes that neuroscience is only beginning to explore. This idea is not necessarily new as it is at the heart of ideas suggested by psychodynamic theorists such as Freud and those who followed his approach. What is new is that the neuroscience data is beginning to help us understand the underlying mechanisms of these effects. So what has neuroscience got to do with becoming more influential? And what can it teach us about how we best communicate with others?

In this chapter, we will look at some of the recent findings in the field of neuroscience and their application to language, communication, interpersonal relationships and influencing others. This book will help you build your personal toolkit for influence. Each chapter brings together recent research in the field of neuroscience and builds a picture of what’s really happening inside our brains when we communicate and connect with others. The book is intended to provide individuals, business communicators, entrepreneurs and leaders with simple and practical tools to better communicate with and influence others – to offer some hard brain science for why many of the soft skills really are the secrets of true influence.

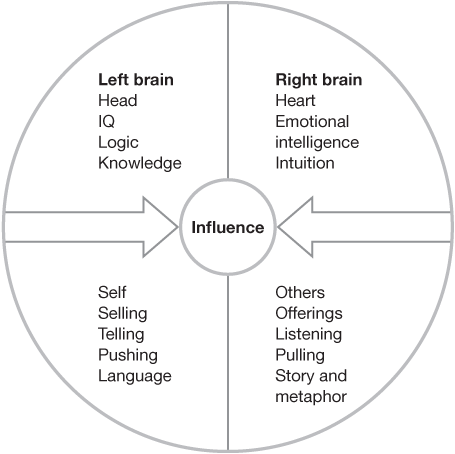

As a corporate communicator for many years, I became increasingly aware that, although my job involved producing information, much of it was corporate jargon, difficult to understand and unlikely to inspire or motivate employees, customers or the public. Business in general, but large corporate businesses even more so, often embody left-brain thinking; IQ is rated much more highly than emotional intelligence, facts and logic are used more than compelling stories to persuade, leaders are valued for using their heads not their hearts. There is a gap between the style and communication approach of many senior leaders and communicators who wanted to simplify, connect and simply tell the story better. And this is where neuroscience helps by offering communicators and influencers the scientific rationale for why emotions, stories and empathy are more likely to speak to the brains of the audience and therefore inspire, motivate and influence. The table below looks at thinking styles and how they relate to the functions performed by the left and right halves of the brain.

We can use the metaphor of right and left brain as a useful shortcut for thinking about how to influence different preferences and in different organisational cultures or contexts. It’s important to match preferences and to ‘speak the same language’; this operates at the level of the individual as well as the organisation/culture. You can use the language of neuroscience to frame your reasoning when talking to CEOs about the power of storytelling and emotional intelligence. If you are more of a right-brain thinker yourself, develop your communication flexibility and adapt to the style of those you need to persuade.

2nd rule of influence:

When preparing to influence an audience to your cause, it’s important to involve their heart as well as their mind so, alongside facts and intellect, share your emotions and tell a story. In business we often look to convince others by telling the information story, but if we want to influence we need to be better at telling the inspiration story.

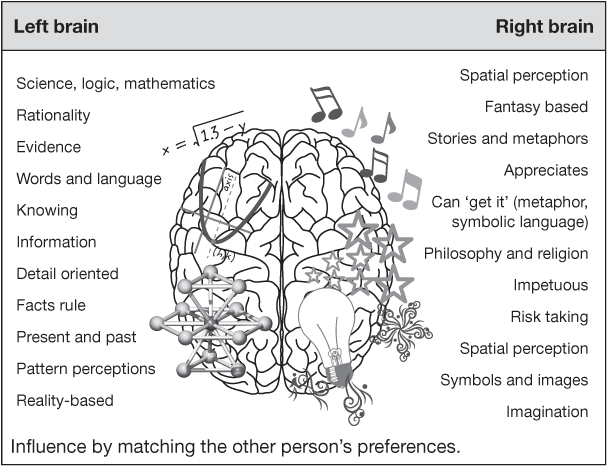

What motivates us: fight–flight

Human beings are driven by two powerful forces: one pushing us forwards to approach something and one pulling us back to avoid something. We have strong tendencies to move toward or away from things. These two core motivations are the brain’s most primitive survival mechanisms and are coded into our physiology and neurology. Broadly speaking, work converging from animal and human studies suggests that the left hemisphere of the brain supports approach behaviours while the right hemisphere is more concerned with withdrawal or avoidance behaviours. Approach and avoid behaviours are processed in separate hemispheres, it is believed, so that multiple approach and avoidance behaviours can be co-ordinated at one time and won’t interfere with each other. Processing in these two hemispheres happens at multiple levels, some of which is conscious and some of which occurs so rapidly that we are not aware. Whether we are approach or avoid oriented seems to be linked to individual differences (personality traits), and this is linked to activity in the lateralised regions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on the left and right side, respectively (see Fig. 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 The brain is structured for approach or avoid behaviours.

The brain’s limbic system (sometimes known as the reptilian brain) is positioned at the top of the spinal column. From this position, it can rapidly send signals down the spinal column via long-range motor neurons to get us to move. Within the limbic system is the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure comprising multiple nuclei (groups of neurons) that acts as the brain’s warning system (see Fig. 1.3). The right amygdala orients us to potential threat while the left amygdala is more concerned with ongoing threatening stimuli (a more sustained response to threat). For real emergencies and life-threatening situations, the low-level processing takes over and co-ordinated activity in the system cascades a series of instructions allowing us to move out of danger before we are even fully aware. Neurons in our motor cortex fire and make us move before the visual cortices in the occipital lobe have had time to process what our eyes have seen. So it’s faster than sight.

FIGURE 1.3 (a) The regions of the frontal cortex (subdivided into different cortices) are the seats of human reasoning, planning and topdown guidance of thinking and attention. When the frontal cortex is working well, we are able to regulate emotions and keep our attention on the task in hand. (b) The brain under stress. The pre-frontal lobe experiences reduced functioning as the limbic system hijacks attention. The hypothalamus, striatum and amygdala come on-line and are activated to prepare the body for fight or flight.

Source: Adapted from Arnsten, A F T (2009) Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function, Nature Reviews – Neuroscience, 10, 410–422. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd and Nature Publishing Group © 2009.

The amygdala also floods our body with the stress hormones adrenaline (short-term or acute threat) and cortisol (longer-term threats) that prime us for action. In conditions of acute stress, the sympathetic nervous system is activated via a sudden release of hormones (including adrenaline) which result in increased heart rate, accelerated breathing, sweating and blood pumping around the body preparing it for action (fighting or fleeing). This is why when we are really stressed and having a panic attack, it literally does feel like we are going to die as this primitive part of the brain is activated (and does not have the sophistication to know that there is not any real and actual danger to the individual).

In our modern world, the fight–flight response is often triggered inappropriately, particularly under conditions of chronic stress. While we no longer have to fight off predators, we do continue to experience social threats in the same way as we would a sabre-toothed tiger. Here are some of the common modern-day threats that trigger our fight–flight response:

- having to meet unrealistic deadlines;

- experiencing a lack of respect;

- being treated unfairly;

- not being appreciated;

- feeling that you’re not being listened to or heard.

If we continue to experience low-level amydgala hijacks at work, our capacity for creativity, problem-solving and decision-making are all reduced, which is why it’s so important for managers and leaders to help to manage the brain states of employees. It is not possible for the body to stay in this hyped up state for long periods of time and soon the parasympathetic nervous system is activated to move us back into a more relaxed state. In this mode, creativity, problem-solving and decision-making skills are restored. Our fight–flight response is the most primitive and powerful emotional trigger we can experience and overrides rational thinking every time.

Case study

The US scientist, Adrian Raine, advises students in his criminal behaviour class to pretend to be asleep if they become aware of an intruder in their apartment because 90 per cent of the time thieves are only interested in grabbing what they want and running. Adrian was able to test out his own advice when holidaying in Turkey with his girlfriend when he woke to see an intruder standing above him in his bedroom in the middle of the night. Adrian said:

information from the senses reaches the amygdala twice as fast as it gets to the frontal lobe. So before my frontal cortex could rein back the amygdala’s aggressive response, I’d already made a threatening move toward the burglar. This in turn immediately activated the intruder’s fight–flight system. Unfortunately for me, his instinct to fight also kicked in. … He hit me so hard on the head that I saw a streak of white light flash before my eyes.

Even though Adrian had been giving this rational advice to his students for years his primitive limbic system overrode logic in a split second.

Source: Raine, A (2013) The Anatomy of Violence, pp. 3–4

The seven core emotions that drive behaviour

Emotions act as the brain’s shortcut to guide our approach and avoidance behaviour. Although the brain codes experiences as ‘good’, ‘bad’ or ‘neutral’, there are seven core human emotions that are universally recognised regardless of culture or geography. These are happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, contempt and surprise (see Fig. 1.4). These core emotions form the basis of our evolutionary journey from hunter gatherers to cyber-surfers and motivate us to either ‘approach’ or ‘avoid’ something in our environment. Sadness, fear, disgust and contempt are all ‘away from’ or avoid emotions, while anger can be either away from (withdrawal or stonewalling) or towards (aggression, criticism and derision).

FIGURE 1.4 Core emotional motivators.

In his 2000 book Integrative Neuroscience, the neuroscientist, Evian Gordon, says that the brain’s organising principle is to minimise danger and maximise reward, which means that everything we experience comes with an emotional ‘tag’ that is either good (toward) or bad (away from). Happiness is our only true ‘toward’ emotion while the emotion of surprise is a fleeting, transitional emotion until the moment we determine whether the surprise is pleasant or not. Surprise may be considered a type of emotional ‘pause’ as we gather further information to inform whether this is pleasant or unpleasant. These core emotions can be grouped into two distinct motivational drives; towards and away from. And when we think about influence, whether we want to sell a product or service, sell an idea or a social movement or inspire people to support a change, we need to be clear about how it will bring the audience closer to something they want (toward) or to avoid something they don’t want (away from).

Every time you communicate to persuade somebody you need to be aware of these two primary motivations. Advertisers use these primary motivations all the time, from selling cars (toward: freedom, independence, comfort) to breath freshener (away from: social rejection).

What’s their motivation?

The brain is designed to alert us to things that are threatening and has more circuits to detect threat than it does to detect reward. So we are predisposed to a more negative orientation because if we miss a threat we can die, whereas if we miss something more positive it will not kill us. This is a very simple but important idea for influence. The table below gives some reasons why, if we’re not clear about how these human motivations work, we will fail to convince.

| Toward message | Mismatch |

| A CEO announces a major change and develops an upbeat, positive message in the hope of getting everyone’s support and buy-in. | Major change is experienced as a threat and the employees experience an emotional ‘away from’ reaction to the announcement. There is a disconnect between the speaker and audience. |

| You want to get your boss’s support for an innovative new project and you focus on all the positive messages. | You fail to convince your boss because you do not take into consideration how you will manage risks and why your project should be chosen above others. |

The science of emotions

Most of us like to believe that we make decisions based on our ability to weigh up logic and facts and, ultimately, to reason about our choices. Few of us like to believe we are predominantly influenced by emotion. Since Descartes famously stated ‘I think therefore I am’, the role of the intellect has been esteemed and elevated with emotions often seen as less reliable guides for our choices. But in the last 20 years neuroscientists have been researching the role emotions play in dictating our choices about what we buy and who we vote for, and the decisions we make about our lives. And what they’re discovering is that many of our decisions that we think are based on ‘rational’ thinking are in fact driven by often unconscious emotional responses.

Antonio Damasio’s book Descartes, Error explored the role emotion plays in our ability to reason effectively. Damasio’s research focused on the study of patients who suffered damage to the parts of the brain that affect decision-making and emotion. In one of his most famous experiments, Damasio worked with a patient called Elliot who had suffered frontal lobe damage affecting his emotional centres but leaving his intellectual capabilities intact. Damasio said:

‘(Elliot’s) intelligent quotient (IQ) was in the superior range ... perceptual ability, past memory, short-term memory, new learning, language, and the ability to do arithmetic were intact’ (p. 960) … ‘the tragedy of this otherwise healthy and intelligent man was that he was neither stupid nor ignorant, and yet he acted often as if he were. The machinery for his decision making was so flawed that he could no longer be an effective social being…’ (p. 889).

Damasio was one of the first neuroscientists to explore brain areas related to emotional ability and the role this plays on our decision-making and the influence emotions have on our higher order cognitive functioning. His work shows that, in order to make effective decisions about our lives, we need to have feelings about them.

Since the publication of Descartes, Error, laboratories across the world have begun to turn their attention to the influence of emotion across a spectrum of research in order to understand more about human behaviour. It’s this research that helps us understand the scientific basis for the role emotions play in persuading and influencing others. Think back to some important decisions you have made recently and complete the exercise below.

Exercise

Think about three important decisions you’ve made in the last year.

- What criteria did you use to make the decision?

- What was the balance between logical thinking and emotional input?

- Have you ever put aside strong emotions to choose something on logic alone (perhaps to buy something you could afford rather than really loved)?

Where does emotional intelligence reside in the brain? A 2003 study by Reuven Bar-On et al. (exploring the neurological substrate of emotional and social intelligence) identified the specific brain centres that govern self-awareness, emotions and empathy: the amygdala, which is located in the midbrain is a neural hub for emotion; the somatosensory cortex helps us empathise with others; and the insula cortex makes us aware of our own body state and therefore helps us tune into others; the anterior cingulate helps us to control our impulses and handle strong emotions, and the prefrontal cortex, which is our brain’s executive centre, helps us solve interpersonal problems, express our feelings and relate to others. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.5.

FIGURE 1.5 The regions of the social brain. Key regions include the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, anterior insula and the temporoparietal junction. These regions together help us to make sense of the social world and understand the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of others.

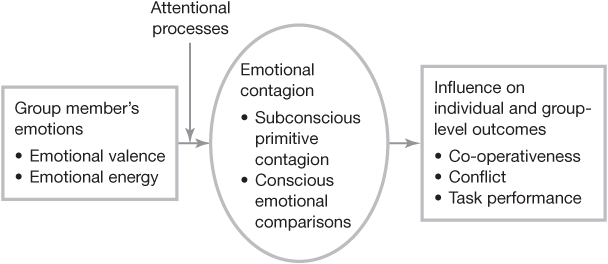

Emotions are contagious

In one experiment, scientists brought together two strangers and asked them to sit silently in a room. Neither of the participants spoke, but within only two minutes, the most emotionally expressive person had managed to convey their emotions to the other person. Our brains transmit emotions to one another through chemical neurotransmitters in the brains of both people. We’ve developed an extraordinary capacity to pick up the subtle emotional cues and feelings of other people without us being consciously aware of it. Emotions are literally contagious.

A study carried out by Barsade in 2002 showed that when business school undergraduates participated in a leaderless group discussion with a confederate who was trained to manipulate their energy and pleasantness they were able to influence the group dynamic, showing that emotional contagion occurs in groups and that we are ‘walking mood inductors’, continuously influencing the mood, judgements and behaviours of others (Barsade, 2002, p. 666).

Barsade’s model (see Fig. 1.6) shows how the energy and valence of a team member works at conscious and subconscious levels in the rest of the group to influence what happens in the team.

FIGURE 1.6 A model of group emotional contagion.

Source: Barsade, S G (2002) The ripple effect: emotional contagion and its influence on group B behaviour, Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 644.

The research on emotional contagion shows how important your own emotional state is when you give that important presentation, that leaders can shift the emotions of employees during difficult times and that managers can raise team performance by managing their own emotional state. Preparing our emotional state is as important as preparing our content. We may need our IQ to help us put the deal together, but we need our EQ to close it.

Understanding others: mirror neurons

But it is not just about the message. In fact even more important – is about understanding your audience, whether that’s an individual person you want to sell your idea to, your team, your boss or new customers you want to find for your business. It’s also about your ability to create rapport, empathy and connection with others, and over the last 20 years, neuroscience has been looking at the role our mirror neuron system plays in our ability to ‘read’ other people, to understand others’ intentions and to pick up on others’ emotions instinctively. Managing our own emotions and preparing our emotional state is just as important as preparing our message when we want to build relationships, empathy and rapport.

Brain plasticity

For most of the 20th century we believed the brain was unalterable after a critical period in childhood, but neuroscience is now showing that the brain can change throughout our life and that both the physical structure and the physiology of the brain can be changed by our experiences. Every time we practise a new skill and every time we change our thinking, our habits and our responses we build new neural pathways that become more and more automatic. Learning the skills of influence is like learning any new skills; whether you want to be a more confident speaker, a more creative writer or a more inspiring leader of your business or community, it really is about developing opportunities to practise and hone your skills. The text introduces exercises that you can make part of your daily habits to help you strengthen and expand your toolkit for influence and persuasion.

The power of visualisation: set your goal

According to research, when we set a goal our brain creates an image as if we have already accomplished it because the brain can’t distinguish between a memory of something that actually happened and an image of a future event. But what many of us discover is that it’s easy to set a goal but not so easy to maintain our focus on the goal when we face setbacks and challenges. Soon we begin to experience self-doubt and anxiety and, unless we can deal with these, they can soon morph into full-blown fear. Fear affects our brain by shutting down our executive function and focusing our attention on a narrow field; getting away from whatever it is that threatens us. Fear extinguishes our creative and imaginative spark and blocks our brain from problem-solving and risk-taking. So the biggest barrier to achieving your goal is the fear you experience, not the challenge itself or the setbacks. All of these can be overcome. By understanding how fear shuts down the brain, we can practise something equally as powerful to help us stay focused and on track to achieve our goals, and that’s the power of goal-setting and using the power of the mind to build new pathways to success.

Case study

Early research into the power of mental visualisation began in sports, and one of the most famous experiments was conducted by a Russian scientist who was asked to work with three different groups of Olympic athletes to find out whether the mind can cause the body to raise its performance and, if so, what was the optimum balance between mental and physical training. The first group of athletes were asked to spend 100 per cent of their time on physical training, the second group spent 75 per cent of their time on physical training and 25 per cent on mental training, the third group spent 50 per cent of their time on performing mental visualisation exercises and 50 per cent on physical training and the fourth group spent 75 per cent of their time on mental training and 25 per cent on physical training. It was the athletes in group four who spent 25 per cent of their time on physical training and 75 per cent on mental visualisation who had the highest performance results.

Since the early research, mental visualisation has become standard practice for many sports people. Only recently, Wayne Rooney, the England striker, said in an interview:

Part of my preparation is I go and ask the kit man what colour we’re wearing – if it’s a red top, white shorts, white socks or black socks. Then I lie in bed the night before the game and visualise myself scoring goals or doing well. You’re trying to put yourself in that moment and trying to prepare yourself, to have a ‘memory’ before the game.

Sources: Mackay, H (2013) Mental training and visualization can help you live your dream, South Florida Business Journal, 18 January 2013 (http://www.bizjournals.com/southflorida/print-edition/2013/01/18/mental-training-and-visualization-can/html?page=all).

Jackson, J (2012) Wayne Rooney reveals visualisation forms important part of preparation, The Guardian, 17 May, 2012 (http://wwwtheguardian.com/football/2012/may/17/wayne-rooney-visualisation-preparation).

Influence in action

Influence doesn’t really exist – the word itself is called a nominalisation (Chapter 4), which means that we take a verb (an action) and turn it into a noun (a thing). Influence is made up of a combination of different skills and abilities, such as being clear and concise about what you want to say, delivering your message with credibility and confidence, using persuasive language and being able to adapt when things don’t go the way you want. So it will help to get clear about what specific skills you’d like to improve and in what situations you’d like to be more influential. Is it at work with your boss or colleagues? Do you need to be more influential as a manager with your team? Would you like to be able to sell your ideas to new customers? Or do you need to seek funding for a new project? Take some time to sit down quietly and write the answers to the following questions:

- Who do you want to influence?

- How will being more influential support you in your personal or professional life?

- In what contexts do you want to be more influential?

- In which situations are you already influential?

- How can you use what you already do well in one context and move it over to a new situation?

- Once you have more influence what will it do for you?

- What stops you from being more influential right now?

- If you could have three new skills or capabilities to help you be more influential, what would they be?

- Of these three, which one will give you the biggest benefit?

- What do you need to stay on track as you develop your skills of influence?

Once you set your goal you need to find ways to stay on track. Thoughts create images in the mind that kick-start a chain reaction of neural and chemical responses; when you think about something that is deeply upsetting you experience very different emotional and physiological responses in your body compared to when your thoughts are inspiring and encouraging. Our mind has a habit where one thought quickly leads to the next and the next in a ‘themed’ chain reaction – it’s easy to find yourself going down very different emotional roads depending on how you think about something. If we experience a setback, our inner critic can be quick to make judgements: ‘I knew they wouldn’t like it’; ‘I’m not smart enough or experienced enough or good enough’. Before we know it we begin to respond from the limbic brain which starts the fight–flight or freeze response; we become defensive, we want to run away and avoid the situation, or we feel stuck and anxious. But understanding about how our brain works can help us find ways to deal with these reactions.

Visualisation activates the brain to release a neurotransmitter called dopamine which is part of the brain’s reward system and makes us feel good. While dopamine kick-starts our motivation, we need to maintain a steady dose to keep us on track when things get tough. Each time we visualise a compelling goal, our brain releases another dose of dopamine, so do what successful athletes do and make mental visualisation a regular part of your preparation – reimagine, reinvigorate and rebuild your goal, every step of the way – the more we practise anything, from playing the piano to goal-setting, the more it becomes wired into our brain circuitry.

Use words, pictures, feelings or sounds to give your brain a rich internal experience when focusing on your goal. Remember the golden rule of brain science; dopamine helps you stay on track and gives you a positive emotional boost. Here are some daily practices that you can experiment with and see what works best for you.

- Daily diary: at the start or end of each day spend five minutes writing about your goal. Make a note of everything you’ve done that day to move you closer towards achieving it. If you’ve experienced negative thoughts or emotions write about these. These thoughts come from a desire to protect ourselves and stay safe; treat them with compassion and acknowledge them as an important part of the process. They have no more or no less power than we give them.

- Mental visualisation: take some quiet time and imagine yourself in the situations where you want to be more influential. See yourself there in full colour 3D technicolour, notice what you are wearing and feel the positive and powerful emotions that go along with your visualisation. You may like to hold a specific image in mind like a symbol, or you may like to direct your own internal movie that you can run in your mind whenever you have some quiet time.

If you are preparing to deliver a presentation, speech or stand in front of an audience, see yourself standing in front of them and watch them acknowledge you, thank you, praise you. If you are starting up in business imagine yourself receiving your first big order from an important customer. If you’re going for a new job or wanting to sell your new project to your boss, imagine seeing their face smiling at you and thanking you for your great idea. Make your images multidimensional, colourful and emotional. - Auditory goal-setting: some people are very ‘auditory’ and are deeply drawn to sound. If that’s you, choose a specific word or sentence that you can repeat to yourself. Write it down and speak or read the words every day. You might like to play a song that brings up powerful and positive emotional and mental associations while you imagine yourself achieving your goal.

- Kinaesthetic: pick the emotions that you want to experience when you are being your ‘influential self’ and go deeply inside them to notice their timbre, tone, shape or style. Wrap the emotion around you as if it’s a warm, soft coat. Find a physical object you can use to remind yourself of your goal every time you touch it. Put it in your pocket, hold it in your hand, close your eyes and imagine yourself achieving your goal. Our brain records images, sounds and feelings in different areas and we each have different preferences for which sense is the most compelling for us – build a rich multisensory experience of your goal so that you build broad, deeper and lasting neural associations and pathways across all areas of your brain.

- The morning pages: Julia Cameron in her 1994 book, The Artist’s Way, recommends doing a daily practice she calls ‘the morning pages’. I’ve used this practice on and off for so many years and I find it helps me stay on track, work out what’s blocking me, and helps me find other ways to get around it. Here are the instructions:

Every morning, write three longhand pages of whatever comes into your head, it can be anything from deep insights to shopping lists. You can write about your dreams, your memories, your holiday plans, irritations, petty gripes –anything and everything that comes into your mind. Do not judge, just keep writing. It’s not about thinking it all through and planning it, it’s about letting it flow through from your mind to the page. Morning pages will help you in more ways than you know, try it for a month and see what happens.

- Daily walks: daily walking is a bit like the morning pages; there’s something mysterious that happens when we are dealing with a problem or a challenge in our mind and we take it out for a walk. This is another practice that I do and can recommend, particularly if you are under stress. Exercise is proven to boost our self-esteem, mood and sleep quality and even to help us become more creative.

Brain Rules:

- Brain plasticity: our daily habits of behaviour and thinking help to shape the brain’s neural pathways.

- Mirror neurons: we have a unique ability to understand and connect with others through our mirror neuron system. Tune in to others and use your emotions to build empathy and rapport.

- Exercise: prepares the brain for peak performance.

- Visualisation: the brain does not know the difference between what is imagined and what is ‘real’. Use the power of the mind to code in success.

Top Tips:

- Get clear about your intention – in which contexts do you want to be more influential?

- Choose the skills that will help you get what you most want.

- Practise a little and often.

- Use successes and failure equally to hone your skills and reset your course.