CHAPTER 14 IT Risk Analysis and Risk Management

Overview

This chapter integrates most of the concepts discussed in previous chapters into an overall framework to deal with information security. The previous chapters have taken a bottom-up approach to security, discussing individual concepts in detail. This chapter takes a top-down approach, beginning with the concerns of society and top management as they relate to information security. These constituencies are less concerned with the technology and more interested in minimizing the economic impacts of information security. The phrase “IT risk management” organizes all issues associated with information security, utilizing inputs from both management and technology experts.

Issues important to top management typically receive lot of attention from many quarters. Since top management cares about risk management,1 a number of popular IT risk-management frameworks have emerged. We provide a quick tour of these frameworks. We then distill ideas from these frameworks to create a risk-management framework that is consistent with the standard frameworks we have used for other related concepts in earlier chapters. At the end of this chapter, you should know:

- The relevance of risk management to top management

- IT risk-management frameworks

- Risk analysis – identification and assessment

- Risk management – mitigation, preparation, and response

Introduction

Risk is a quantitative measure of the potential damage caused by a specified threat. In prior chapters, we have built up the knowledge base required to analyze and manage risks. In Chapter 6, we have discussed threats in detail. We can build on that idea in this chapter to discuss an issue that draws the attention of top management – risk management.

Since risk management is driven by top management concerns, in this introductory section, we set the topic of risk management within the overall context of managing an organization. We then discuss the standard risk-management framework developed by NIST to guide IT risk-management activities.

Risk management as a component of organizational management

The performance of an organization is assessed using some measure of profitability.2 More profitable organizations are more valuable than less profitable organizations. Accordingly, the primary focus of managers is to maximize their organization's profits. We may write this managerial concern as:

Manager's decision problem = max (profit) = max (Revenues − cost)

Managers can accomplish this goal by using some combination of increasing revenues (generally by raising prices or selling more units) or by reducing costs. Much of the management literature and most of the typical MBA curriculum are devoted to guiding managers to reach these goals. However, when running organizations on a day-to-day basis, managers find unusual things happening all the time, many of which can significantly affect the organization's profit-maximizing equation. For example, we have seen earlier how TJ Maxx made provisions for $118 million to deal with the fallout from its credit card incident. Since these incidents can affect the organization's profits, they need to be managed. At a very high level, managing the financial impacts of unusual events is called risk management. To represent this, we can modify the manager's decision problem as:

max (Revenues − cost − Δ), where Δ is the impact of unusual events on the organization.3

There are broadly two approaches to risk management: (1) making risks (Δ) predictable and (2) minimizing and preparing for these risks.

The standard approaches for making risks predictable are insurance and hedging. These are some of the most important activities of the financial sector of the economy. For example, buying flood insurance for your datacenter makes the financial impact of flood events predictable, equal to the annual premium paid to buy the insurance. While the idea sounds unusual, you should know that this is an important component of IT risk management. We (the authors) are not experts in designing and pricing financial instruments, so we leave the details of this approach to the experts in finance. However, we would like to emphasize that top management understands this approach well and always considers it seriously. So, do not be surprised if you hear the term “insurance” in the context of IT risk management.

That leaves us with minimizing and preparing for risks. This is the approach we discuss in the rest of this chapter.

Another classification that we find interesting is between offense and defense. All sports teams have a mix of offense and defense. In our domain, organizations invest in IT as an offensive measure in the profit equation – to attack costs and complexity or to battle for customers in more markets. Information security is the defensive arm of the equation. It focuses on ensuring that the organization's existing competitive advantage is not lost due to improper IT implementations.4,5

With this background, we will now look at the standard IT risk-management framework developed by NIST.

Statutory reporting of risk factors by top management

As an example of the importance of risk management to top executives, publicly traded companies are required by law to report the risk factors facing their company to investors.

Item 1A. Risk Factors.6

Set forth, under the caption “Risk Factors,” where appropriate, the risk factors described in Item 503(c) of Regulation S-K (§229.503(c) of this chapter) applicable to the registrant. Provide any discussion of risk factors in plain English in accordance with Rule 421(d) of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.421(d) of this chapter). Smaller reporting companies are not required to provide the information required by this item.

From §229.503(c),7 risk factors for newly issued securities include, among other things, the following: (1) lack of an operating history; (2) lack of profitable operations in recent periods; (3) financial position; (4) business or proposed business; or (5) lack of a market for your common equity securities or securities convertible into or exercisable for common equity securities.

Example: AAPL 10-K (Oct 31, 2012)8

In its 10-K filed on 10/31/2012, among other risk factors, Apple reported the following two risk factors, which directly to IT:

The Company's business and reputation may be impacted by information technology system failures or network disruptions.

The Company may be subject to breaches of its information technology systems, which could damage business partner and customer relationships, curtail or otherwise adversely impact access to online stores and services, and could subject the Company to significant reputational, financial, legal, and operational consequences.

Risk-management framework

A framework is a structure for supporting something else. In the management literature, frameworks are used when a large number of ideas are to be organized in a manner that can be understood and memorized by many people, i.e., management frameworks support the organization of related concepts to accomplish a goal of interest.

Many frameworks are popular for risk management, including CERT's OCTAVE, ISO 27002 from the International Standards Organization, and the NIST 800-39 guidelines on managing information security risk. In addition, leading vendors such as Microsoft9 and Google10 publish their own recommendations for information security risk management. All of these guidelines present similar ideas and represent the results of the collective efforts of the best minds in the industry to manage IT risks. Any of these guidelines would be an excellent basis to develop an information risk-management plan for your organization.

It is strongly recommended that you adopt and follow one of the standard risk-management frameworks to develop your risk-management plan, making any adjustments for your specific context. It is generally a bad idea to develop your own risk-management plan from scratch. You are very likely to miss many important concerns, which you will only discover at great cost when a threat exposes the omission in your risk-management framework. It would be wise to remember Benjamin Franklin on this matter, “experience keeps a dear school, yet fools learn in no other.”

Our preference in this book is to present ideas in a consistent manner across chapters. We believe it facilitates comprehension and memorability. We find the NIST 800-39 guidelines to be the most suitable for our purpose since it is very compatible with the way we have presented information in earlier chapters. Accordingly, we base the rest of this chapter on these guidelines. We integrate many of the ideas covered in earlier chapters (such as the threat model and the disaster life cycle) within the NIST risk-management framework. For completeness, toward the end of this chapter, we also provide a quick overview of the other popular frameworks.

The NIST 800-39 framework

The NIST recommendations for managing information security risk are published as special publication 800-39.11 The current version is dated on March 2011. The 800-39 guidelines were developed with inputs from the Civil, Defense, and Intelligence Communities to provide an information security framework for the federal government. The 800-39 guidelines (and the discussion in this chapter) are very general and do not attend to the specific concerns of high-security environments such as military bases or special laws such as HIPAA. Those environments will use more stringent procedures than those suggested by NIST 800-39. However, the 800-39 framework is very useful for the majority of commercial and non-profit organizations and hence are suitable for our purposes. If you work in a high-security environment such as a military base or bank, the institution will provide you with additional risk-management guidelines specific to that environment.

IT risk is defined as the risk associated with the use of information systems in an organization. This is one of the many risks facing organizations. NIST recognizes that risk management is not an exact science. It is the best collective judgment of people at all ranks and functions within an organization about suitable measures to protect the organization. The 800-39 framework recommends that senior leadership be involved in IT risk management, and that IT risk management be integrated in the design of business processes.12

IT risk-management components

The 800-39 framework identifies four components of IT risk management – (1) the risk frame, (2) the risk assessment, (3) the risk response once the risks are assessed, and (4) ongoing risk monitoring based on the experiences gained from risk response activities. These are organized as shown in Figure 14.1.

The risk frame establishes the context for risk management by describing the environment in which risk-based decisions are made. This clarifies to all members in the organization the various risk criteria used in the organization. These criteria include (i) assumptions about the risks that are important; (ii) responses that are considered practical; (iii) levels of risk considered acceptable; and (iv) priorities and trade-offs when responding to risks. Risk framing also identifies any risks that are to be managed by senior leaders/executives.

In a classic example of risk framing that was highlighted during the 2012 Presidential debates, there was only one reference to terror in the President's 2001 State of the Union address. The very next year, after the 9/11 attacks, there were 36 references to terror in the 2002 State of the Union address.

Doesn't that make clear a change in the risk-frame of the executive branch of the US Government in just one year?

Within the context of the risk frame, the risk assessment component identifies and aggregates the risks facing the organization. Recall our definition of risk as a quantitative measure of the potential damage from a threat. Risk assessment develops these quantitative estimates by identifying the threats, vulnerabilities in the organization and the harm to the organization if the threats exploit vulnerabilities. We discuss risk assessment in greater detail in the next section.

Risk response addresses how organizations respond to risks once they are determined from risk assessments. Risk response helps in the development of a consistent, organization-wide, response to risk that is consistent with the risk frame. Following standard business procedures, risk response consists of (i) developing alternative courses of action for responding to risk; (ii) evaluating these alternatives; (iii) selecting appropriate courses of action; and (iv) implementing risk responses based on selected courses of action.

Risk monitoring evaluates the effectiveness of the organization's risk-management plan over time. Risk monitoring involves (i) verification that planned risk response measures are implemented; (ii) verification that planned risk responses satisfy the requirements derived from the organization's missions, business functions, regulations, and standards; (iii) determination of the effectiveness of risk response measures; and (iv) identification of required changes to the risk-management plan as a result of changes in technology and the business environment.

The arrows in Figure 14.1 illustrate the risk-management processes and the information and communication flows among the risk-management components. The activities in the outer circles are performed sequentially, moving from risk assessment to risk response to risk monitoring. The risk frame informs all the sequential step-by-step activities. For example, the threats identified from the risk frame serve as inputs to the risk assessment activity. Similarly, the outputs from the risk assessment component (risks) serve as the input to the risk response component.13

Risk assessment

Once the risk frame is established, we can build on the threat model developed earlier to create a risk assessment model.

Disambiguating risk assessment and risk analysis

The risk assessment component in the NIST 800-39 framework includes two activities – identifying risks and quantifying these risks. What NIST calls risk assessment is often also called risk analysis, with the term risk assessment referring to the quantification aspect of NIST's risk assessment component.

The specific context should help you disambiguate the meaning of the term risk assessment.

Risk assessment model

The threat model introduced earlier is reproduced in Figure 14.2. Threats involve motivated agents attacking assets. When conducting threat analysis, we typically do not conduct a formal analysis of the potential outcomes of the threats. Our concern during threat analysis is limited to identifying potential problems.

For example, one of the threats identified was a remote hacker (agents) compromising the user credentials database (asset), by stealing these credentials (action). During threat analysis, we did not consider the potential impact of such a threat. Specifically, we did not worry about what the hacker might do with such information.

Risk assessment can be seen as adding an analysis of outcomes to the identified threats. Our definition of a risk as a quantitative measure of the potential damage caused by a specified threat can be written as:

Risk = damage as a result of a specified threat, or

Risk = damage(threat), i.e., risk is the damage output as a function of the threat input

Since the threat itself is composed of an agent, an action, and an asset, we can write the equation for risk as:

Risk = damage (agent, action, asset)

This is shown in Figure 14.3. We can use this figure to identify risks and write them down as risk statements, which provide all the information necessary to communicate information about risks to concerned parties. Building on our example threat of a hacker stealing user credentials, we can write the associated risks as:

Risk 1: A remote hacker (agent) may steal (action) user credentials (asset) and try these credentials to access banking websites (action). This may lead to lawsuits, which will drain profits as well as management time (damage).

Risk 2: A remote hacker (agent) may steal (action) user credentials (asset) and try these credentials to access banking websites (action). This may lead to adverse publicity, which may hurt our business in the short term (damage).

In other words, the same threat may be associated with multiple risks, if the threat can cause multiple forms of damage.

The risk assessment model of Figure 14.3 shows that even a small set of assets and agents can lead to a large number of threats and risks. For example, the combination of two agents (remote attacker and disgruntled employee) and two assets (information assets and hardware assets) can result in four potential threats. If we add two forms of damage to the mix (financial loss, information loss), we have eight potential risks to consider. In the real-world, even the smallest businesses deal with tens of assets, agents (who can be driven by multiple motives), and damages, which can result in tens of thousands of potential risks (if we just multiply the number of agents, assets, actions, and damages). But most organizations can only deal with perhaps 5–10 risks at any given time. This is why risk frames are important – to prune out unlikely risks.

Once the risks are identified, quantitative measures for the risks are developed by estimating the likelihood and potential damage upon occurrence of the risk. We then calculate the risk as the product of the likelihood and the magnitude. Continuing with our example of the hacker, say we estimate the probability of such an attack in the coming year at 1%. Also, say that for risk 2, we estimate the monetary damage from lost sales at $10,000 in profits. We can quantify the risk in this case as:

Risk = likelihood × magnitude = 0.01 × $ 10,000 = $ 100.

By developing similar estimates for all the identified risks, we can prioritize the risks within our risk frame.

Other risk-management frameworks

The NIST 800-39 framework is a very general IT risk-management framework. There are some other information security risk-management framework, with the ISO 27000 series and the CERT OCTAVE being among the most popular. There are many consulting firms which help organizations to implement the recommendations of these standards. We provide a brief overview of these two standards here for completeness.

ISO 27000 series

The International Standards Organization (ISO) has reserved the ISO 27000 series of standards (i.e., standards starting with the digits 27) for information security matters. As of December 2012, this series includes six standards ranging from ISO 27001 to ISO 27006. These standards cover the following topics:

ISO 27001: The standard that specifies the requirements for an information security management system (ISMS)

ISO 27002: The standard that specifies a set of controls to meet the requirements specified in ISO 27001

ISO 27003: Guidance for the implementation of an ISMS

ISO 27004: Measurement and metrics for an ISMS

ISO 27005: The standard for information security risk management

ISO 27006: The standard that provides guidelines for the accreditation of organizations that offer ISMS certification

The ISO 27001 standard states that the ISO adopts a process approach for implementing information security. All processes follow Deming's Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) model. During the planning phase, organizations establish policies and procedures to manage information risks. These procedures are operated in the do phase. During checking, process performance is measured against the plan specifications and presented to management for review. In the act phase, review results are used to improve policies and procedures in the next iteration of the plan phase.

You may note the parallels between the NIST 800-39 and ISO 27001 standards. The NIST assess phase maps to the ISO plan phase, the respond phase to the do phase, and the monitor phase to the ISO check and act phases.

ISO 27002 documents a set of security techniques, which map to the controls we have discussed throughout this book. The controls in the standard are divided into the following sections: (i) asset management; (ii) human resources security; (iii) physical and environmental security; (iv) communications and operations management; (v) access control; (vi) information systems acquisition, development, and maintenance; (vii) information security incident management; (viii) business continuity management; and (ix) compliance.14

ISO 27005 specifies that the information security risk-management process consists of seven sequential steps: (i) context establishment; (ii) risk assessment; (iii) risk treatment; (iv) risk acceptance; (v) risk treatment plan implementation; (vi) risk monitoring and review; and (vii) risk-management process improvement. Following the PDCA recommendation of ISO 27001, ISO 27005 aligns these activities with the four phases as shown in Table 14.1.

As you can see, there is considerable overlap between the ISO and NIST recommendations as they relate to information security.

OCTAVE

Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) hosts the well-known Software Engineering Institute (SEI). SEI is a federally funded organization that has over the years taken the stewardship for coordinating various activities important to the software industry. It started off by developing recommended guidelines for improving the software development process. In recent years, it has taken leadership in information security and maintains the central repository of bug reports released by major software vendors. Another popular initiative of the SEI is the OCTAVE methodology for information security management.

Table 14.1 Alignment between ISO 27001 information security (IS) management system components and ISO 27005 IS risk-management process components

OCTAVE stands for Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, Vulnerability Evaluation. The methodology corresponds to the risk assessment phase of the NIST 800-39 framework. The description of the OCTAVE methodology provided below is adapted from the overview provided at the SEI website:15

The OCTAVE Method was developed with large organizations in mind (300 employees or more). These organizations generally maintain their own IT infrastructure and have the capability to manage their own information security operation. OCTAVE uses a three-phased approach to examine organizational and technology issues, assembling a comprehensive picture of the organization's information security needs. The three phases are:

Phase 1: identifying critical assets and the threats to those assets

Phase 2: identifying the vulnerabilities, both organizational and technological, that expose those threats, creating risk to the organization

Phase 3: developing a practice-based protection strategy and risk mitigation plans to support the organization's mission and priorities

OCTAVE is comprised of a series of workshops, either facilitated by outside experts or conducted by an interdisciplinary analysis team of three to five of the organization's own personnel. The method takes advantage of knowledge from multiple levels of the organization. These activities are supported by a catalog of good or known practices, as well as surveys and worksheets that can be used to elicit and capture information during focused discussions and problem-solving sessions.

As you may have observed, there are many parallels between the OCTAVE and other information security risk-management frameworks discussed earlier (NIST 800-39 and ISO 27000).

IT general controls for Sarbanes–Oxley compliance

Thus far in this chapter, we have discussed general information security risk-management frameworks that are usable in a wide range of industries. While these frameworks should be helpful in most contexts, in contexts where the stakes are very high, specific legal requirements for IT risk-management methodologies have emerged. One such context is financial reporting in publicly traded companies. This context has been a big driver of recruitment of freshly graduated information security professionals in the last decade. It has introduced terms such as SOX, section 302, section 404, internal control, and IT general controls into the information security lexicon. Given this importance, we provide an overview of this context in this section.

The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002

In the final years of the 20th century, America witnessed one of the most euphoric rises in stock prices in its financial history. The business potential of the Internet led to investors bidding up the prices of any company associated with the Internet. The phenomenon is now known as the “dot-com boom.” Analysts developed metrics such as “dollars per eyeball” to justify these prices. Whereas companies whose stock prices are over 20 times annual income are generally considered expensive, during this time companies sported billion dollar valuations with no profits and many companies sported valuations in excess of 100 times annual profits. In the late stages of this frenzy, when people began to question these lofty valuations and companies came under pressure to justify their stock prices, executives at some well-known firms forged their account-books either to show sales that did not actually occur (MCI-Worldcom) or to hide costs (Enron). Many of these executives profited personally from these forgeries.

When the cases came to trial, leaders at these companies denied culpability and took the plea that they had signed off on the financial statements based primarily on their trust in their accounting staff and auditors. They argued that the firms' operations were so complicated that it was impossible for them to know all aspects of the financial statements. However, management experts, the public, and lawmakers were convinced that the managers knew exactly what they were doing and the pleas of ignorance were merely attempts to exploit legal loopholes and avoid penalties.

These trials brought to light two important details of stock markets. One, that the retirements of most Americans were tightly linked to stock markets because most retirement funds have no choice but to invest the majority of their assets in the US stock markets to achieve the growth required to help people retire gracefully. When large companies such as Enron and MCI-Worldcom manipulated their statements and eventually collapsed, it hurt the retirement assets of almost every American worker. Two, that firm leaders could push a lot of wrongdoing in their firms through verbal and implicit directions that left no paper trail that could be used during court trials.

Under heavy pressure to do something, Congress passed the Sarbanes–Oxley act in 2002. The act is named after its two primary sponsors, Senator Paul Sarbanes (D-MD) and Representative Michael G. Oxley (R-OH). The voting pattern indicates the overwhelming legislative support at the time for the law. It received 423 of a possible 434 votes in the house and 99 of the 100 possible votes in the senate.

Sarbanes–Oxley – important provisions

From the legal perspective, the law had one major impact. Sections 302 and 906 created a new criminal provision, making CEOs and CFOs of publicly traded firms criminally liable for untrue statements in public filings. CEOs and CFOs are now personally liable for the veracity of financial information presented in public filings. Prior to Sarbanes–Oxley, prosecutors had to establish malicious intent for untrue statements to be considered a criminal offense. For reference, the relevant provisions of the act are reproduced below.

EXHIBIT 14.1 EXCERPT FROM SEC. 302 OF THE SARBANES–OXLEY ACT

SEC. 302. CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINANCIAL REPORTS.

(a) REGULATIONS REQUIRED.—The Commission shall, by rule, require, for

each company filing periodic reports under section 13(a) or 15(d)

of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78m, 78o(d)), that

the principal executive officer or officers and the principal finan-

cial officer or officers, or persons performing similar functions,

certify in each annual or quarterly report filed or submitted under

either such section of such Act that—

(1) the signing officer has reviewed the report;

(2) based on the officer's knowledge, the report does not contain

any untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a

material fact necessary in order to make the statements made,

in light of the circumstances under which such statements were

made, not misleading;

(3) based on such officer's knowledge, the financial statements,

and other financial information included in the report, fairly

present in all material respects the financial condition and

results of operations of the issuer as of, and for, the periods

presented in the report;

(4) the signing officers—

(A) are responsible for establishing and maintaining internal

controls;

(B) have designed such internal controls to ensure that mate-

rial information relating to the issuer and its consolidated

subsidiaries is made known to such officers by others within

those entities, particularly during the period in which the

periodic reports are being prepared;

(C) have evaluated the effectiveness of the issuer's internal

controls as of a date within 90 days prior to the report;

and

(D) have presented in the report their conclusions about the

effectiveness of their internal controls based on their

evaluation as of that date;

…

EXHIBIT 14.2 EXCERPT FROM SEC. 906 OF THE SARBANES–OXLEY ACT

SEC. 906. CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINANCIAL REPORTS. … ‘’(c) CRIMINAL PENALTIES.—Whoever— ‘’(1) certifies any statement as set forth in subsections (a) and (b) of this section knowing that the periodic report accompanying the state- ment does not comport with all the requirements set forth in this sec- tion shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both; or ‘’(2) willfully certifies any statement as set forth in subsections (a) and (b) of this section knowing that the periodic report accompanying the statement does not comport with all the requirements set forth in this section shall be fined not more than $5,000,000, or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.‘’.

EXHIBIT 14.3 SECTION 404 OF THE SARBANES–OXLEY ACT

SEC. 404. MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT OF INTERNAL CONTROLS.

(a) RULES REQUIRED.—The Commission shall prescribe rules requiring each

annual report required by section 13(a) or 15(d) of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78m or 78o(d)) to contain an inter-

nal control report, which shall—

(1) state the responsibility of management for establishing and

maintaining an adequate internal control structure and proce-

dures for financial reporting; and

(2) contain an assessment, as of the end of the most recent fiscal

year of the issuer, of the effectiveness of the internal control

structure and procedures of the issuer for financial reporting.

(b) INTERNAL CONTROL EVALUATION AND REPORTING.—With respect to the

internal control assessment required by subsection (a), each reg-

istered public accounting firm that prepares or issues the audit

report for the issuer shall attest to, and report on, the assessment

made by the management of the issuer. An attestation made under this

subsection shall be made in accordance with standards for attesta-

tion engagements issued or adopted by the Board. Any such attesta-

tion shall not be the subject of a separate engagement.

From a business perspective, section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley act introduced the concept of standards-based verification of internal control. Prior to the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley act, auditing firms used their own battle-tested procedures to verify that firms had robust processes to prevent fraud. However, the events of the dot-com boom revealed that auditing firms could be persuaded through fees and promises of future engagements to compromise on their assessments and certify suspect financial reports. Accordingly, the Sarbanes–Oxley act required that the verification of internal procedures be based on rules that were established by government, not the industry. Section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley act is shown below. The directive in the section that is relevant to our purposes is highlighted in bold.

The net result is that, since 2003, firms are required to verify that their internal controls comply with the standards established by the Sarbanes–Oxley act. We provide a high-level overview of standards and associated procedures in the rest of this section.

PCAOB and auditing standards

Sarbanes–Oxley (popularly called SOX) created a body called the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to develop the standards to be used for SOX attestations. Adapting from the organization's website,16

The PCAOB is a nonprofit corporation established by Congress to oversee [the audits of public companies and broker-dealers, with the goal of investor protection]. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which created the PCAOB, required that auditors of U.S. public companies be subject to external and independent oversight for the first time in history. Previously, the profession was self-regulated. The five members of the PCAOB Board, including the Chairman, are appointed to staggered five-year terms by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), after consultation with the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Secretary of the Treasury. The SEC has oversight authority over the PCAOB, including the approval of the Board's rules, standards, and budget. The Act established funding for PCAOB activities, primarily through annual fees assessed on public companies in proportion to their market capitalization and on brokers and dealers based on their net capital.

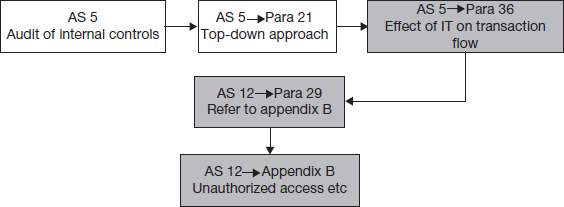

The PCAOB has published standards for all aspects of auditing.17 The standards of greatest interest to us are AS5 - “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statements” and AS12 – “Identifying and Assessing Risks of Material Misstatement.” AS 5 guides the overall SOX engagement, something you are quite likely to participate in if you join one of the professional auditing firms. Within the SOX audit, AS 12 provides guidance for IT.

Section 21 of the AS 5 standard specified the overall direction of a SOX audit as:

21. The auditor should use a top-down approach to the audit of internal control over financial reporting to select the controls to test. A top-down approach begins at the financial statement level and with the auditor's understanding of the overall risks to internal control over financial reporting. The auditor then focuses on entity-level controls and works down to significant accounts and disclosures and their relevant assertions.

Section 36 of AS 5 directs auditors to paragraph 29 and appendix B of AS 12 to deal with the impacts of IT upon the audit process:

36. The auditor also should understand how IT affects the company's flow of transactions. The auditor should apply paragraph 29 and Appendix B of Auditing Standard No. 12, Identifying and Assessing Risks of Material Misstatement, which discuss the effect of information technology on internal control over financial reporting and the risks to assess.

Section 29 of As 12 essentially directs auditors to appendix B of the standard:

29. The auditor also should obtain an understanding of how IT affects the company's flow of transactions. (See Appendix B.)

Finally, appendix B of AS 12 includes the following:

APPENDIX B – CONSIDERATION OF MANUAL AND AUTOMATED SYSTEMS AND CONTROLS

…

B4. The auditor should obtain an understanding of specific risks to a company's internal control over financial reporting resulting from IT. Examples of such risks include:

- Reliance on systems or programs that are inaccurately processing data, processing inaccurate data, or both;

- Unauthorized access to data that might result in destruction of data or improper changes to data, including the recording of unauthorized or non-existent transactions or inaccurate recording of transactions (particular risks might arise when multiple users access a common database);

- The possibility of IT personnel gaining access privileges beyond those necessary to perform their assigned duties, thereby breaking down segregation of duties;

- Unauthorized changes to data in master files;

- Unauthorized changes to systems or programs;

- Failure to make necessary changes to systems or programs;

- Inappropriate manual intervention; and

- Potential loss of data or inability to access data as required.

For convenience, Figure 14.4 shows how the above guidelines for IT audits flow from section to section in the auditing standards.

Internal controls

What is the ultimate goal of all the activity associated with Sarbanes–Oxley? The term used is “internal control over financial reporting.” This is defined by the PCAOB in appendix A of AS 5 as:

A5. Internal control over financial reporting is a process designed by, or under the supervision of, the company's principal executive and principal financial officers, or persons performing similar functions, and effected by the company's board of directors, management, and other personnel, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the reliability of financial reporting and the preparation of financial statements for external purposes in accordance with GAAP and includes those policies and procedures that –

(1) Pertain to the maintenance of records that, in reasonable detail, accurately and fairly reflect the transactions and dispositions of the assets of the company;

(2) Provide reasonable assurance that transactions are recorded as necessary to permit preparation of financial statements in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles, and that receipts and expenditures of the company are being made only in accordance with authorizations of management and directors of the company; and

(3) Provide reasonable assurance regarding prevention or timely detection of unauthorized acquisition, use, or disposition of the company's assets that could have a material effect on the financial statements.

Internal control over financial reporting is a subset of the overall control activities at the firm. In the Sarbanes–Oxley domain, control activities are defined as procedures, methods, and policies that responsible persons use to reduce the likelihood of occurrence of risky events to acceptable levels. This definition is consistent with the definition of IT security controls we have used in this book – safeguards used to minimize the impact of threats.

IT general controls

The bulk of the internal control audit activities are performed by auditors and accountants. However, these professionals rely on IT experts to assist in the evaluation of the controls exemplified in Appendix B of AS 12. These activities have traditionally been called IT general controls.

The current versions of the auditing standards do not seem to have a definition for the term “IT general controls.” However, AS 2, which has been superseded by AS 5, included in para 50.18

50. Some controls (such as company-level controls, described in paragraph 53) might have a pervasive effect on the achievement of many overall objectives of the control criteria. For example, information technology general controls over program development, program changes, computer operations, and access to programs and data help ensure that specific controls over the processing of transactions are operating effectively. In contrast, other controls are designed to achieve specific objectives of the control criteria. For example, management generally establishes specific controls, such as accounting for all shipping documents, to ensure that all valid sales are recorded.

While even AS 2 only provided example and did not formally define IT general controls, para 50 suggests a definition. Based on para 50 of AS2, general controls may be contrasted with specific controls in that general controls provide the underlying platform for the accomplishment of many specific controls. For example, if an IT system allows users without passwords to record transactions, the likelihood of fraudulent transactions increases significantly, weakening the effectiveness of specific controls designed to verify different business activities. Therefore, maintaining a secure IT infrastructure through IT general controls is important to reliably verify business activity. Based on this, we define IT general controls as control activities performed by IT that ensure the correct processing of business transactions by the organization.

In a Sarbanes–Oxley engagement, IT experts are involved in the auditing of IT general controls.

Procedure for verification of IT general controls as part of a SOX audit

Following the top-down guiding principle of AS 5, the industry has developed the following procedure for an audit of IT general controls over financial reporting.19

- Look at the firm's financial statements

- Identify material line items

- What an average prudent investor reasonably ought to know

- Identify business processes feeding into these items

- Identify IT platforms that support these processes – OS, database, applications, web-server, network

- Verify that IT general control objectives are satisfied for these platforms

- Report material weaknesses

- Deficiency that can result in material mis-statements to occur or remain undetected

This process is repeated annually, to comply with the provisions of the SOX act. For # 5 in the list above, 12 control objectives have been identified based on industry best practices, including items such as managing changes and managing data.20

Compliance versus risk management

The example of Sarbanes–Oxley in the domain of IT general controls over financial reporting that was introduced in the previous section shows that a lot of risk-management activities are mandated by law and regulations. Earlier, we have defined compliance as the act of following applicable laws, regulations, rules, industry codes, and contractual obligations. If the bulk of risk-management work is defined by laws and regulations, you might wonder why any organization should take the effort of developing its own risk-management plan based on NIST 800-39 or ISO 27000. Why not outsource risk management to legislators and industry experts, and simply comply with the laws, regulations, industry codes, etc. that these experts develop?

If you give this some thought, you will realize that compliance is only a subset of risk management, requiring a minimal set of risk-management activities to prevent catastrophe that can affect others. Compliance does not regulate risks that affect only you or your organization. For example, you are entitled to risk your money on lotteries, squander your income on unwise purchases, and consume alcohol within the privacy of your home, etc. Since any adverse outcomes of these actions are limited to you alone, there are no regulations or codes preventing you from performing these activities. However, when you drive on the road, your dangerous conduct can put other drivers at risk. Therefore, we require drivers to comply with safe driving laws and there are stiff penalties for driving under the influence of alcohol.

Similarly, in IT risk management, compliance activities ensure that your organization's conduct does not put investors and other organizations at risk. But you alone are responsible for ensuring that your actions do not put your own organization at risk. Risk management covers everything that you do to prevent harm to yourself.

Selling security

IT security is not an easy sell. Upper management usually thinks in terms of Return on Investments and oftentimes it is difficult to quantify the return on something that “may” happen, like a power failure or a hacker incident. Even though it is easier to justify the expenses based on existing, known incidents, certain organizations are still hesitant to commit resources to security.

One of the best strategies is to try to include a certain percentage to be spent in security in every project started within IT. For instance, a project involving Identity and Access Management may also include the cost of software needed to encrypt personal data such as Social Security Numbers. And if the software agreement is negotiated correctly, the same software may be licensed to include the permission to encrypt other restricted data on other servers as well.

Unfortunately, one of the easiest ways to obtain funds is to capitalize on incidents that happened with other, similar organizations. A leak of Social Security Numbers on nearby Universities will without a doubt raise questions about the internal security of your own University. The students will be asking how protected their SSNs are, and maybe so will the local media. During these times, IT may receive windfalls of funds to improve the security stance of the infrastructure. It is important to have a strategy always ready to be able to use these situations and not just waste funds purchasing resources that are not needed.

Example case–online marketplace purchases

On December 5, 2012, the US Attorney for the Eastern District of New York announced the arrests of six Romanian and one Albanian national for defrauding US customers on popular Internet marketplaces such as eBay, AutoTrader.com, and Cars.com. The arrests involved co-operation among law enforcement agencies in Romania, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States.

The fraudsters posted detailed ads for expensive items such as cars and boats on the popular online markets though none of the posted items actually existed. They used co-conspirators called “arrows” in the United States to open bank accounts using high-quality fake passports. These arrows responded to enquiries from potential buyers and collected payments.

Payments from unsuspecting victims were transferred out of the United States by the arrows as cash or wire transfers. In one case, $18,000 in cash was mailed out of the US inside speakers. In another case, money was used to buy an expensive watch, which was then mailed to the fraudsters. The total estimated earnings of the gang was $3 million.

REFERENCE

http://www.justice.gov/usao/nye/pr/2012/2012dec05.html

SUMMARY

In this chapter, we looked at risk analysis and the different frameworks available for risk analysis. We used risk analysis to relate the contents of this book to the overall managerial objectives of a firm. The NIST 800-39 risk analysis framework allowed us to present all the information in earlier sections of the book in a format consistent with recommended standards for risk analysis. We saw that risk analysis associates each threat with all possible outcomes and provides a mechanism to quantify risks for comparison and evaluation. We also saw a specific risk-management framework mandated by the Sarbanes–Oxley act, which is used by publicly traded firms to assure investors of the reliability of financial reporting.

CHAPTER REVIEW QUESTIONS

- What is risk? What in your opinion are the three greatest IT risks you face in your personal life?

- What is risk management? List one or two activities you can perform to make the risks identified in q1 more predictable.

- List one or two activities you can perform to minimize and prepare for the IT risks you identified in q1.

- What are frameworks? Why are they used in management? Very briefly (in 1–2 sentences), name a framework you have studied in another class. How did the use of a framework help your understanding of the topic organized by the framework?

- What is the objective of the NIST 800-39 framework?

- What are the types of organizational risks listed in NIST 800-39 (page 1, para 2 of the standard)?

- Look at the latest 10-K filed by Apple Computer (or if you prefer, another leading publicly traded technology vendor, say Microsoft, Oracle, Dell, IBM, HP). List all the risks identified by the company as risk factors (summarize them as short phrases each). Classify each of these risks as one of the organizational risks listed in NIST 800-39.

- Provide a brief overview of the NIST 800-39 risk-management framework. Draw a figure showing the components of the framework and the relationships of these components to each other.

- What is IT risk management? How is IT risk management related to an organization's overall risk management?

- What is the IT risk frame, as defined by NIST 800-39? What is the role of the risk frame in IT risk management?

- What is IT risk assessment, as defined by NIST 800-39? What is the role of risk assessment in IT risk management?

- What is IT risk response, as defined by NIST 800-39? What is the role of the risk response in IT risk management?

- What is IT risk monitoring, as defined by NIST 800-39? What is the role of risk monitoring in IT risk management?

- How are risks related to threats?

- During the risk identification phase of risk assessment, what are the items that need to be determined to identify a risk?

- Write the risks you identified q1 as risk statements, following the examples in the chapter as the template. Clearly identify all the components of the risk in each risk statement.

- For each risk in q16, use your best judgment to estimate the likelihood and impact of each risk. Using these estimates, quantify each risk and rank the risks based on these estimates.

- Provide a brief overview of the ISO 27000 series of risk management standards developed by the International Standards Organization (ISO). How are they related to the NIST 800-39 standards. If you had to choose one of these, which one would you choose as your reference standard for IT risk management? Why?

- Provide a brief overview of the OCTAVE methodology developed by the SEI. How is it related to the NIST 800-39 and ISO 27000 standards?

- What are some of the important provisions defined by the Sarbanes–Oxley act?

- What are some of the important differences between the provisions of sections 302 and 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley act.

- What is internal control as defined by the Sarbanes–Oxley act?

- What are auditing standards?

- Briefly describe the top-down auditing procedure for the verification of IT general controls as part of a Sarbanes–Oxley audit.

- How is risk management different from compliance?

EXAMPLE CASE QUESTIONS

- Read the announcement by the US Attorney's office at the link provided in the case. List as many mechanisms used by the fraudsters to convince potential buyers of the legitimacy of the advertisement?

- Based on this incident, what precautions would you recommend to a friend contemplating the purchase of an expensive item online?

HANDS-ON ACTIVITY–RISK ASSESSMENT USING LSOF

In this activity, you will learn the use of the lsof command to audit which commands are using network connections and produce a risk assessment of your Linux Virtual Machine.

To begin, switch to the super user account and run ‘lsof –i’ to view all open network connections:

[alice@sunshine ∼]$ su - Password: thisisasecret [root@sunshine ∼]# lsof -i COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME sshd 1862 root 3u IPv4 11083 0t0 TCP *:ssh (LISTEN) sshd 1862 root 4u IPv6 11085 0t0 TCP *:ssh (LISTEN) ntpd 1870 ntp 16u IPv4 11113 0t0 UDP *:ntp ntpd 1870 ntp 17u IPv6 11114 0t0 UDP *:ntp ntpd 1870 ntp 18u IPv6 11118 0t0 UDP v6.sunshine.edu:ntp ntpd 1870 ntp 19u IPv6 11119 0t0 UDP [fe80::a00:27ff:fef6:cadf]:ntp ntpd 1870 ntp 20u IPv4 11120 0t0 UDP sunshine.edu:ntp ntpd 1870 ntp 21u IPv4 1878265 0t0 UDP 10.0.2.15:ntp mysqld 2148 mysql 10u IPv4 11438 0t0 TCP *:mysql (LISTEN) master 2276 root 12u IPv4 11742 0t0 TCP sunshine.edu:smtp (LISTEN) master 2276 root 13u IPv6 11744 0t0 TCP v6.sunshine.edu:smtp (LISTEN) httpd 2316 root 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) qpidd 2335 qpidd 10u IPv4 12079 0t0 TCP *:amqp (LISTEN) qpidd 2335 qpidd 11u IPv6 12080 0t0 TCP *:amqp (LISTEN) dnsmasq 13558 nobody 4u IPv4 1877904 0t0 UDP *:domain dnsmasq 13558 nobody 5u IPv4 1877905 0t0 TCP *:domain (LISTEN) dnsmasq 13558 nobody 6u IPv6 1877906 0t0 UDP *:domain dnsmasq 13558 nobody 7u IPv6 1877907 0t0 TCP *:domain (LISTEN) dhclient 13624 root 6u IPv4 1878166 0t0 UDP *:bootpc httpd 31152 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31153 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31154 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31156 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31157 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31158 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31159 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN) httpd 31160 apache 4u IPv6 11985 0t0 TCP *:http (LISTEN)

The output from this command gives you several valuable pieces of information about the programs running on your system such as:

- The name of the program that is running (COMMAND)

- The user the program is running as (USER)

- The process id of the program (PID)

- The port the program is connecting to and/or awaiting connects on (NAME)

The final column (NAME) is the most interesting. The entries are in the format server:port (STATE) where server is the computer (name or IP address) the process is connecting to and port is the name of the service the process is using. The port number the process is connected to is resolved to a service name by looking it up in /etc/services. Port numbers can be used for multiple services, so this lookup isn't always reliable, but it is usually a good guess.

Connection listings starting with an asterisk (*) are not connecting to an external server; they are listening for a connection to be made to them, hence the LISTEN state appended to many of these entries.

Search the web for more information on each of the processes listed in the lsof output and compile the information into a table.

Example:

QUESTIONS

- In your opinion, what services (if any) could be a security risk and may need to be disabled?

- Instead of disabling a service, what other controls could be put in place to mitigate the risk?

CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISE–RISK ESTIMATION BIASES

In recent years, there has been a lot of research on how people are biased in estimating risks. Cass Sunstein, one of the most eminent legal scholars of our time stated that “diverse cultures focus on very different risks, with social influences and peer pressures accentuating some fears and reduce others. Cascades, the availability heuristic, loss aversion, and group polarization are highly relevant here.” In an article in the New York Times, Prof. Jared Diamond described how people ignore hazards with a low likelihood of occurrence at each opportunity, but with a very high frequency of opportunities, for e.g., driving. In a related stream of research called cultural cognition, Prof. Dan Kahan of Yale University states that “culture precedes facts,” in that people selectively accept and dismiss facts in a manner that supports their views.

REFERENCES

Sunstein, C.R. “Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle,” Cambridge University Press, March 2005. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract = 721562

Diamond, J. “That daily shower can be a killer,” New York Times, 01/28/2013

Schneier, B. Cryptogram, February 1, 2013

Kahan, D.M., Slovic, P., Braman, D., and Gastil, J. “Fear of democracy: A cultural evaluation of Sunstein on risk,” Harvard Law Review, 2006, 119, Yale Law School, Public Law Working Paper No. 100, Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 317. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract = 801964

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

- During IT risk assessment, what are some ways that estimation biases can lead to overestimation of insignificant risks and underestimation of important risks?

- It is suggested that overestimation of a risk necessarily leads to an under-recognition of some other important risk. Do you agree with this assessment? Why, or why not?

DESIGN CASE

Now that you have finished the class, it is time to wrap up. You have been working at Sunshine University for a year now and the President and Provost ask you to put together a Risk Assessment for the organization. Create a simplified RA for the year based on all the Design Cases you have worked on so far. Here are some guidelines:

- Review and re-evaluate all Design Cases for all chapters in the book in order to prepare the Risk Assessment document.

- Make the RA easy to read.

- Use graphs to demonstrate your points.

- Compare the current status of Sunshine University with other Universities when possible.

- Research possible challenges brought up by new technologies.

- Close with a few items proposed to improve the security stance of the University.

1In spite of this concern, only about 5% – 25% of Fortune 500 companies are prepared to deal with crises. These crisis-prepared companies have to tackle about 33% fewer crises, live about 25% longer, have double the ROA and have higher reputations than companies that just react to crises (Mitroff, I. I. and M. C. Alpaslan (2003). “Preparing for evil.” Harvard Business Review 2003(April): 109–115.).

2Not all organizations aim for profitability. Non-profitable organizations such as universities are a huge sector of the economy, accounting for over 10% of all US jobs (http://www.urban.org/nonprofits/index.cfm). While these organizations measure their outputs using criteria such as number of students graduated and number of patents obtained, even these organizations are concerned with putting their resources to optimal use, and their managers share most of the same risk-managers concerns as managers in for-profit organizations

3Δ stands for delta, an industry-standard term for deviations from normal behavior

4One of our students summarized this idea by reminding us of the quote: “Offense sells tickets, defense wins championships”

5Another related area is ensuring that new risks created in the organization due to IT investments are well managed. For example, some spectacular financial losses have occurred because of rapid financial trading enabled by IT systems. This is also not discussed in this chapter. But an excellent discussion can be found in Westerman, G. and Hunter, R. (2007). IT Risk: Turning Business Threats into Competitive Advantage (Hardcover). Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press

6http://www.sec.gov/about/forms/form10-k.pdf

7http://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/229.503

9http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc163143.aspx

10https://cloud.google.com/files/Google-CommonSecurity-WhitePaper-v1.4.pdf

11http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-39/SP800-39-final.pdf (accessed 12/20/2012)

12A very interesting link on IT risks for school administrators: http://dangerouslyirrelevant.org/2012/08/26-internet-safety-talking-points.html (accessed 07/22/2013). Appeared in Bruce Schneier's blog, 9/15/2012

13The 800-39 document uses bi-directional arrows everywhere in the figure. We have used directed arrows to connect the outer circles. We believe this better represents the sequential nature of activities and information flows from risk assessment to response to monitoring

14We have only touched briefly upon business continuity management in this book. This is because most fresh college graduates will only have limited responsibility for business continuity. We have chosen to maintain our focus on the information security topics that are most relevant to college graduates within the first 4–5 years after graduation

15http://www.cert.org/octave/octavemethod.html (accessed 12/28/2012)

17http://pcaobus.org/Standards/Auditing/Pages/default.aspx

18http://pcaobus.org/standards/auditing/pages/auditing_standard_2.aspx

19For more details, please see the ISACA document at http://www.isaca.org/Knowledge-Center/Research/ResearchDeliverables/Pages/IT-Control-Objectives-for-Sarbanes-Oxley (accessed 1/1/2013)

20See figure 1 on page 11 of the ISACA document referred above